Cup of Solid Gold

The "Cup of Solid Gold" (simplified Chinese: 巩金瓯; traditional Chinese: 鞏金甌; pinyin: Gǒng Jīn'ōu; Wade–Giles: Kung3 Chin1-ou1, IPA: [kʊ̀ŋ tɕín.óu]), adopted by the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) on 4 October 1911, was the first official national anthem of China. The title wishes for the stability of the "golden cup," a ritual instrument that symbolized the empire. Six days after the anthem was adopted, however, the Wuchang Uprising took place and quickly led to the fall of the Qing. The "Cup of Solid Gold" was never performed publicly.

| English: Cup of Solid Gold | |

|---|---|

| 鞏金甌 | |

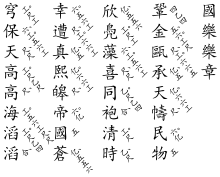

Sheet music in Gongche notation | |

Former national anthem of | |

| Lyrics | Yan Fu |

| Music | Bo Tong |

| Adopted | 4 October 1911 |

| Relinquished | 12 February 1912 |

Background: non-official anthems

| Historical Chinese anthems | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

Imperial Chinese dynasties used music for various ceremonies, but never had official anthems representing the country. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, Qing China was constantly in contact with foreign countries and started to require a national anthem "for diplomatic convenience."[1]

Qing diplomats were the first to suggest adopting an official anthem. Zeng Jize (1839–1890) — eldest son of statesman Zeng Guofan — was the Qing envoy to France, England, and Russia for several years starting in 1878. Around 1880, he composed a song called Pu Tian Yue to be played as China's anthem in various state ceremonies and suggested the Qing adopt it as its official anthem, but the court did not approve. That song's lyrics and melody have both been lost.[2]

When Li Hongzhang (1823–1901) visited Western Europe and Russia in 1896 as a special envoy charged with learning about foreign institutions after the disastrous end of the Sino–Japanese War in 1895, he was again asked to provide China's national anthem for performance at state receptions. He hastily adapted some court music to a slightly modified jueju poem by Tang-dynasty (618–907) poet Wang Jian and presented that song as the Qing anthem.[2] That song later became known as the Tune of Li Zhongtang, but was never officially recognized as a national anthem.[2]

Another non-official anthem was written for the new Qing ground forces that were established in 1906. Entitled Praise the Dragon Flag, it was played on ceremonial occasions, but like the songs promoted by Zeng Jize and Li Hongzhang, was never officially adopted as the Qing national anthem.[2]

A Chinese version of the Japanese national anthem Kimigayo (adopted by the Meiji regime in 1888) was played in the new-style schools that taught modern topics like science and engineering.[3] The Chinese lyrics — "To unify old territories, our ancient Asian country of four thousand years sighs in sorrow for the Jews, India, and Poland. Reading the history of those who have lost their countries, we shiver in our hearts!" — emphasized the Social Darwinist themes of ethnic crisis and loss of national territory, but many considered these too far from the usual themes of ceremonial music to be acceptable.[3]

The Cup of Solid Gold

On January 25, 1911, an official from the Ministry of Rites called Cao Guangquan (曹廣權/曹广权) petitioned the Qing court to adopt a stately "national music" (guoyue 國樂/国乐) that could be performed at court ceremonies.[4] He proposed that officials collect both ancient music and examples of state music from abroad and, on that basis, design an anthem for the Qing. The Ceremonial Council (Dianliyuan 典禮院/典礼院), which had just replaced the Ministry of Rites, responded on July 15 of that year.[5] It put Putong (溥侗) (1877–1950) — a Manchu noble and direct descendant of the Daoguang Emperor who served in the Imperial Guard — in charge of writing the melody, whereas Yan Fu (1854–1921), a translator of European scientific and philosophical treatises and an advisor to the Qing Navy, was charged with writing the lyrics.[6] Guo Cengxin (郭曾炘), who had worked for the Ministry of Rites, made some minor modifications at the end.[7]

The Qing government adopted Gong Jin'ou as its national anthem on 4 October 1911.[8] The edict announcing the new anthem, and sometimes even the anthem's music and lyrics, were published in newspapers, and the court instructed the Navy and Army to practice the song, which was also transmitted to China's ambassadors throughout the world.[9] However, the Wuchang Uprising took place on October 10 (six days after the anthem was promulgated) and quickly led to the fall of the dynasty. The foundation of the Republic of China was announced for January 1, 1912, and the last Qing emperor officially abdicated a little more than a month later. Gong Jin'ou was never performed publicly.[10]

Title

Ou (甌) was a kind of wine vessel. Jin'ou (金甌/金瓯), or golden wine vessel, symbolized an "indestructible country".[11] The Qing emperor used such a vessel for ritual purposes. Inlaid with pearls and gems, it was known as the "Cup of Eternal Solid Gold" (Jin'ou Yonggu Bei 金甌永固杯).[11] Because gong 鞏 means "to consolidate" or "to strengthen," the entire title may be translated as "strengthening our hold on the golden cup."[11]

Yan Fu, who wrote the lyrics, glossed the title and first line of the anthem as "Firm and stable be the 'golden cup' (which means the empire)."[12]

Music

The person who was nominally put in charge of the anthem's music was Putong, an imperial relative who was familiar with theatre and Peking opera.[13] Aided by assistants in the Imperial Guard, he composed the music based on the models found in the Complement to the Treatise on Pitch Pipes (Lülü Zhengyi Houbian 律呂正義後編/律吕正义后编; 1746), an imperial compilation that complemented a much shorter 1724 work on ceremonial music commissioned by the Kangxi Emperor.[8]

Lyrics

The lyrics, composed by Yan Fu, are in Classical Chinese.

| Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Wade–Giles | IPA transcription | English translation[14] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

鞏金甌, |

巩金瓯, |

Gǒng Jīn'ōu |

Kung chin'ou |

[kʊ̀ŋ t͡ɕín.óʊ̯ |

Cup of solid gold, |

In the second line, tian chou 天幬/天帱 (literally, the "canopy of Heaven") referred to the Mandate of Heaven, which a legitimate dynasty was supposed to represent.[15] Tongpao 同袍 (lit., "sharing the same robes"), an allusion to a verse in the Book of Poetry, meant "sharing the same goals and loyalties" or being part of the same army.[16] In modern transcriptions of the lyrics, that phrase is often miswritten as tongbao 同胞 ("compatriot"), a term with racial connotations that the Manchu nobles who ruled Qing China purposely wanted to avoid.[17]

Answering a request transmitted by George Ernest Morrison, on 16 March 1912 Yan Fu wrote to British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey to explain the Qing anthem, and ended his letter with a rough translation of the lyrics:[18]

Firm and Stable be the "golden cup" (which means the empire) domed by the Celestial concave. In it, men and things happily prosper. Glad are we who live in the time of Purity. May Heaven protect and secure us from enemies and help us to reach the truly golden age! Oh! The Blue firmament is infinitely high and the seas flow everlastingly.

The character qīng 清 that Yan rendered as "Purity" was also the name of the Qing dynasty.[19]

References

Citations

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 440, note 24.

- Ye 2006.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 440.

- Ye 2006; Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 441.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 441.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, pp. 451–52.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 452.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 442.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, pp. 442–43.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 457.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 443.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 453, citing a letter by Yan to Sir Edward Grey dated 16 March 1912.

- Rhoads 2000, p. 146.

- Site of the Imperial Qing Restoration Organization

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 446.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 446, note 39.

- Ye 2012, p. 265.

- Ye & Eccles 2007, p. 453, citing Lo Hui-min, ed., The Correspondence of G. E. Morrison, Vol. 1, 1895–1912 (Cambridge University Press, 1976), pp. 768–69.

- Yan Fu renders the two lines "xi tong pao, qing shi zao yu 喜同袍,清時幸遭" as "Glad are we who live in the time of Purity". Other sources translate the same lines as "United in happiness and mirth, As long as the Qing rules" (see table above) and "Blest compatriots, the Qing era encounters prosperity" (Ye & Eccles 2007, pp. 446–47)

Works cited

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000), Manchus & Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China 1861–1928, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-97938-0.

- Ye, Xiaoqing 葉小青 (2006), "Da Qing guo de guoge 大清國的國歌 [The Qing National Anthem]", Xungen 尋根, 2006 (3): 90–91, doi:10.3969/j.issn.1005-5258.2006.03.010, archived from the original on 2017-09-06, retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ——— (2012), Ascendant Peace in the Four Seas: Drama and the Qing Imperial Court, Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, ISBN 978-962-996-457-3.

- ———; Eccles, Lance (2007), "Anthem for a Dying Dynasty: The Qing National Anthem through the Eyes of a Court Musician", T'oung Pao, 93 (4/5): 433–58, doi:10.1163/008254307x246946, JSTOR 40376331.

External links

- MIDI audio file

- Rendition on YouTube

- Rendition on youtube without lyrics

- Another rendition on youtube sounding more normal like, not the anthem type sound

- Sheet music, lyrics, and audio

- Chinesische Kaiserhymne (in German)

| Preceded by – |

"Cup of Solid Gold" 1911–1912 |

Succeeded by "Song to the Auspicious Cloud" (1912–1928) |