Western Xia

The Western Xia or Xi Xia (Chinese: 西夏; pinyin: Xī Xià; Wade–Giles: Hsi1 Hsia4), also known to the Mongols as the Tangut Empire and to the Tangut people themselves and to the Tibetans as Mi-nyak,[6] was an empire which existed from 1038 to 1227 in what are now the northwestern Chinese provinces of Ningxia, Gansu, eastern Qinghai, northern Shaanxi, northeastern Xinjiang, southwest Inner Mongolia, and southernmost Outer Mongolia, measuring about 800,000 square kilometres (310,000 square miles).[7][8][9] Its capital was Xingqing (modern Yinchuan), until its destruction by the Mongols in 1227. Most of its written records and architecture were destroyed, so the founders and history of the empire remained obscure until 20th-century research in the West and in China.

Western Xia 西夏 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1038–1227 | |||||||||||||||||||

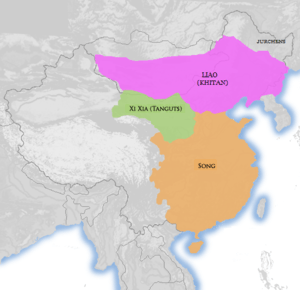

Location of Western Xia in 1111 (green in north west) | |||||||||||||||||||

Western Xia in 1150 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Xingqing (modern Yinchuan) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Tangut, Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Primary: Buddhism Secondary: Taoism Confucianism Chinese folk religion | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1038–1048 | Emperor Jingzong | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1206–1211 | Emperor Xiangzong | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1226–1227 | Emperor Mozhu | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-classical history | ||||||||||||||||||

| 984 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Dynasty established by Emperor Jingzong | 1038 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Subjugated by Mongol Empire | 1210 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Destroyed by Mongol Empire after rebellion | 1227 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1100 est.[1] | 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• peak | 3,000,000[2][3][4] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Barter with some copper coins in the cities (see: Western Xia coinage)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | ||||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BC | ||||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC | ||||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC | ||||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BC | ||||||||

| Western Zhou | ||||||||

| Eastern Zhou | ||||||||

| Spring and Autumn | ||||||||

| Warring States | ||||||||

| IMPERIAL | ||||||||

| Qin 221–207 BC | ||||||||

| Han 202 BC – 220 AD | ||||||||

| Western Han | ||||||||

| Xin | ||||||||

| Eastern Han | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | ||||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | ||||||||

| Jin 266–420 | ||||||||

| Western Jin | ||||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | |||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | ||||||||

| Sui 581–618 | ||||||||

| Tang 618–907 | ||||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | ||||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 |

Liao 916–1125 | |||||||

| Song 960–1279 | ||||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | |||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | Western Liao | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | ||||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | ||||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | ||||||||

| MODERN | ||||||||

| Republic of China on mainland 1912–1949 | ||||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | ||||||||

| Republic of China on Taiwan 1949–present | ||||||||

The Western Xia occupied the area round the Hexi Corridor, a stretch of the Silk Road, the most important trade route between North China and Central Asia. They made significant achievements in literature, art, music, and architecture, which was characterized as "shining and sparkling".[10] Their extensive stance among the other empires of the Liao, Song, and Jin was attributable to their effective military organizations that integrated cavalry, chariots, archery, shields, artillery (cannons carried on the back of camels), and amphibious troops for combat on land and water.[11]

Name

The full title of the Western Xia as named by their own state is 𗴂𗹭𗂧𘜶 reconstructed as /*phiow¹-bjij²-lhjij-lhjij²/ which translates as "Great State of White and Lofty" (大白高國), also named as 𗴂𗹭𘜶𗴲𗂧 "The Great Xia State of the White and the Lofty" (白高大夏國), or called "mjɨ-njaa" or "khjɨ-dwuu-lhjij" (萬祕國). The region was known to the Tanguts and the Tibetans as Minyak.[6][12]

"Western Xia" is the literal translation of the state's Chinese name. It is derived from its location on the western side of the Yellow River, in contrast to the Liao (916–1125) and Jin (1115–1234) dynasties on its east and the Song in the southeast. The English term "Tangut" comes from the Mongolian name for the country, Tangghut (Tangɣud), believed to reflect the same word as "Dangxiang" (traditional Chinese: 党項) found in Chinese literature.

History

Foundations

The Tanguts originally came from the Tibet-Qinghai region, but migrated eastward in the 650s under pressure from the Tibetans. By the time of the An Lushan Rebellion in the 750s they had become the primary local power in the Ordos region in northern Shaanxi. The Tanguts sometimes fell under direct administration by the Tang dynasty. As a result, the Tanguts often cooperated with external powers such as the Uyghurs in opposing the Tang. The situation lasted until the 840s when the Tanguts rose in open revolt against the Tang, but the rebellion was suppressed. Eventually the Tang court was able to mollify the Tanguts by admonishing their frontier generals and replacing them with more disciplined ones.[13]

In 881 the Tangut general Li Sigong was granted control of the Dingnan Jiedushi, also known as Xiasui, in modern Yulin, Shaanxi for assisting the Tang in suppressing the Huang Chao Rebellion (874–884). Li Sigong died in 886 and was succeeded by his brother Li Sijian. After the fall of Tang in 907, the rulers of Dingnan were granted honorary titles by the Later Liang. Li Sijian died in 908 and was succeeded by his son Li Yichang, who was murdered by his officer Gao Zongyi in 909. Gao Zongyi was himself murdered by soldiers of Dingnan and was replaced by a relative of Li Yichang, Li Renfu. Dingnan was attacked by Qi and Jin in 910, but was able to repel the invaders with the aid of Later Liang. Li Renfu died in 933 and was succeeded by his son Li Yichao. Under Li Yichao Dingnan successfully repelled an invasion by the Later Tang. Li Yichao died in 935 and was succeeded by his brother Li Yixing.

In 944 Li Yixing attacked the Liao dynasty on behalf of the Later Jin. In 948 Li Yixing attacked a neighboring circuit under encouragement from the rebel Li Shouzhen but retreated after Li Shouzhen was defeated. Honorary titles were given out by the Later Han to appease local commanders, including Li Yixing. In 960 Dingnan came under attack by Northern Han and successfully repelled invading forces. In 962 Li Yixing offered tribute to the Song dynasty. Li Yixing died in 967 and was succeeded by his son Li Kerui.

Li Kerui died in 978 and was succeeded by Li Jiyun, who died in 980 and was succeeded by Li Jipeng, who died in 982 and was succeeded by Li Jiqian.

Li Jiqian rebelled against the Song dynasty in 984, after which Dingnan was recognized as the independent state of Xia. Li Jiqian died in battle in 1004 and was succeeded by his son Li Deming.

Under Li Deming, the Xia state defeated the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom in 1028 and forced the ruler of the Guiyi Circuit to surrender. Li Deming died in 1032 and was succeeded by his son Li Yuanhao.

In 1036 the Xia annexed the Guiyi and Ganzhou Uyghur states. In 1038 Li Yuanhao declared himself the first emperor (wu tsu or Blue Son of Heaven)[14] of the Great Xia with his capital at Xingqing in modern Yinchuan. What ensued was a prolonged war with the Song dynasty which resulted in several victories. However the victories came at a great cost and the Xia found itself short of manpower and supplies. In 1044 the Xia and Song came to a truce with the Xia recognizing the Song ruler as emperor in return for annual gifts from the Song as recognition of the Tangut state's power. Aside from founding the Western Xia, Li Yuanhao also ordered the creation of a Tangut script as well as translations of Chinese classics into Tangut.

Middle period

After Emperor Jingzong of Western Xia died in 1048, his son Li Liangzuo became Emperor Yizong of Western Xia at the age of two and his mother became the regent. In 1049 the Liao dynasty launched an invasion of Western Xia and vassalized it. Yizong died in 1067 and his son Li Bingchang became Emperor Huizong of Western Xia at the age of six.

Huizong's mother became regent and she invaded Song territory. The invasion ended in failure, and Huizong took back power from his mother. However he died soon after in 1086 and was succeeded by his son Li Qianshun who became Emperor Chongzong of Western Xia at the age of two.

After Chongzong became emperor, his grandmother (Huizong's mother) became regent again and launched invasions of the Liao dynasty and the Song dynasty. Both campaigns ended in defeat and Chongzong took direct control of Western Xia. He ended wars with both Liao and Song and focused on domestic reform.

In 1115, the Jürchen Jin dynasty defeated the Liao. The Liao emperor fled to Western Xia in 1123. Chongzong submitted to the Jin demand for the Liao emperor and Western Xia became a vassal state of Jin. After the Jin dynasty attacked the Song and took parts of the northern territories from them, initiating the Southern Song period, Western Xia also attacked and took several thousands square miles of land.

Chongzong died in 1139 and was succeeded by his son Li Renxiao who became Emperor Renzong of Western Xia. Immediately following Renzong's coronation, many natural disasters occurred and Renzong worked to stabilize the economy.

Destruction by the Mongols

Renzong died in 1193 and his son Li Chunyou became Emperor Huanzong of Western Xia.

In the late 1190s and early 1200s, Temujin, soon to be Genghis Khan, began consolidating his power in Mongolia. Between the death of Tooril Khan, leader of the Keraites, until Temujin's Mongol Empire in 1203, the Keraite leader Nilqa Senggum led a small band of followers into Western Xia.[15] However, after his adherents took to plundering the locals, Nilqa Senggum was expelled from Western Xia territory.[15]

Using his rival Nilga Senggum's temporary refuge in Western Xia as a pretext, Temujin launched a raid against the Western Xia in 1205 in the Edsin region.[15][16][17] The Mongols plundered border settlements and one local Western Xia noble accepted Mongol authority.[18] In 1206, Temujin was formally proclaimed Genghis Khan, ruler of all Mongols, marking the official start of the Mongol Empire. In the same year, Huanzong was killed in a coup by his cousin Li Anquan, who installed himself as Emperor Xiangzong of Western Xia. In 1207, Genghis led another raid into Western Xia, invading the Ordos Loop and sacking Wulahai, the main garrison along the Yellow River, before withdrawing in 1208.[17][19]

In 1209 Genghis undertook a larger campaign to secure the submission of Western Xia. After defeating a force led by Gao Lianghui outside Wulahai, Genghis captured the city and pushed up along the Yellow River, defeated several cities, and besieged the capital, Yinchuan, which held a well-fortified garrison of 150,000.[20] The Mongols attempted to flood the city by diverting the Yellow River, but the dike they built to accomplish this broke and flooded the Mongol camp.[15] Nevertheless, Xiangzong agreed to submit to Mongol rule, and demonstrated his loyalty by giving a daughter, Chaka, in marriage to Genghis and paying a tribute of camels, falcons, and textiles.[21]

After their defeat in 1210, Western Xia attacked the Jin dynasty in response to their refusal to aid them against the Mongols.[22] The following year, the Mongols joined Western Xia and began a 23-year-long campaign against Jin. In the same year Xiangzong's nephew Li Zunxu seized power in a coup and became Emperor Shenzong of Western Xia. Xiangzong died a month later.

In 1219, Genghis Khan launched his invasion of Khwarezmia and Eastern Iran and requested military aid from Western Xia. However, the emperor and his military commander Asha refused to take part in the campaign, stating that if Genghis had too few troops to attack Khwarazm, then he had no claim to supreme power.[23][24] Infuriated, Genghis swore vengeance and left to invade Khwarazm while Western Xia attempted to create alliances with the Jin and Song against the Mongols.[25]

After defeating Khwarazm in 1221, Genghis prepared his armies to punish Western Xia for their betrayal. Meanwhile, Shenzong abdicated in 1223 in favor of his son Li Dewang, who became Emperor Xianzong of Western Xia. In 1225, Genghis attacked with a force of approximately 180,000.[26] After taking Khara-Khoto, the Mongols began a steady advance southward. Asha, commander of the Western Xia troops, could not afford to meet the Mongols as it would involve an exhausting westward march from the capital Yinchuan through 500 kilometers of desert, and so the Mongols steadily advanced from city to city.[27] Enraged by Western Xia's fierce resistance, Genghis ordered his generals to systematically destroy cities and garrisons as they went.[23][25][28] Genghis divided his army and sent general Subutai to take care of the westernmost cities, while the main force under Genghis moved east into the heart of the Western Xia and took Gan Prefecture, which was spared destruction upon its capture due to it being the hometown of Genghis's commander Chagaan.[29]

In August 1226, Mongol troops approached Wuwei, the second-largest city of the Western Xia empire, which surrendered without resistance in order to escape destruction.[30] At this point, Emperor Xianzong died, leaving his relative Emperor Mozhu of Western Xia to deal with the Mongol invasion.[31] In Autumn 1226, Genghis took Liang Prefecture, crossed the Helan Mountains, and in November lay siege to Lingwu, a mere 30 kilometers from Yinchuan.[31][32] Here, at the Battle of the Yellow River, the Mongols destroyed a force of 300,000 Western Xia that launched a counter-attack against them.[31][33]

Genghis reached Yinchuan in 1227, laid siege to the city, and launched several offensives into Jin to prevent them from sending reinforcements to Western Xia, with one force reaching as a far as Kaifeng, the Jin capital.[34] Yinchuan lay besieged for about six months, after which Genghis opened up peace negotiations while secretly intending to kill the emperor.[35] During the peace negotiations, Genghis continued his military operations around the Liupan mountains near Guyuan, rejected a peace offer from the Jin, and prepared to invade them near their border with the Song.[36][37] However, in August 1227, Genghis died of a historically uncertain cause, and, in order not to jeopardize the ongoing campaign, his death was kept a secret.[38][39] In September 1227, Emperor Mozhu surrendered to the Mongols and was promptly executed.[37][40] The Mongols then pillaged Yinchuan, slaughtered the city's population, plundered the imperial tombs west of the city, and completed the effective annihilation of the Western Xia state.[25][37][41][42]

The destruction of Western Xia during the second campaign was near total. According to John Man, Western Xia is little known to anyone other than experts in the field precisely because of Genghis Khan's policy calling for their complete eradication. He states that "There is a case to be made that this was the first ever recorded example of attempted genocide. It was certainly very successful ethnocide."[43] However, some members of the Western Xia royal clan emigrated to western Sichuan, northern Tibet, even possibly Northeast India, in some instances becoming local rulers.[44] A small Western Xia state was established in Tibet along the upper reaches of the Yalong River while other Western Xia populations settled in what are now the modern provinces of Henan and Hebei.[45] In China, remnants of the Western Xia persisted into the middle of the Ming dynasty.[46][47]

Culture

The kingdom developed a Tangut script to write its own Tangut language, a now extinct Tibeto-Burman language.[6][48]

The economy of the kingdom mainly consisted of agriculture, pastoralism, and trade (especially with Central Asia).[49][50]

Tibetans, Uyghurs, Han Chinese, and Tanguts served as officials in Western Xia.[51] It is unclear how distinct the different ethnic groups were in the Xia state as intermarriage was never prohibited. Tangut, Chinese and Tibetan were all official languages.[52]

In 1034 Li Yuanhao (Emperor Jingzong) introduced and decreed a new custom for Western Xia subjects to shave their heads, leaving a fringe covering the forehead and temples, ostensibly to distinguish them from neighbouring countries. Clothing was regulated for different different classes of official and commoners. Dress seemed to be influenced by Tibetan and Uighur clothing.[53]

Religion

The government-sponsored state religion was a blend of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism and Chinese Mahayana Buddhism with a Sino-Nepalese artistic style. The scholar-official class engaged in the study of Confucian classics, Taoist texts, and Buddhist sermons, while the Emperor portrayed himself as a Buddhist King and patron of Lamas.[52] Early in the kingdom's history, Chinese Buddhism was the most widespread form of Buddhism practiced. However, around the mid-twelfth century Tibetan Buddhism gained prominence as rulers invited Tibetan monks to hold the distinctive office of state preceptor.[54] The practice of Tantric Buddhism in Western Xia led to the spread of some sexually related customs. Before they could marry men of their own ethnicity when they reached 30 years old, Uighur women in Shaanxi in the 12th century had children after having relations with multiple Han Chinese men, with her desirability as a wife enhancing if she had been with a large number of men.[55][56][57]

Rulers

| Temple Name | Posthumous Name | Personal Name | Reign Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jǐngzōng 景宗 | Wǔlièdì 武烈帝 | Lǐ Yuánhào 李元昊 | 1038–1048 |

| Yìzōng 毅宗 | Zhāoyīngdì 昭英帝 | Lǐ Liàngzuò 李諒祚 | 1048–1067 |

| Huìzōng 惠宗 | Kāngjìngdì 康靖帝 | Lǐ Bǐngcháng 李秉常[58][59] | 1067–1086 |

| Chóngzōng 崇宗 | Shèngwéndì 聖文帝 | Lǐ Qiánshùn 李乾順[60][61] | 1086–1139 |

| Rénzōng 仁宗 | Shèngdédì 聖德帝 | Lǐ Rénxiào 李仁孝[62] | 1139–1193 |

| Huánzōng 桓宗 | Zhāojiǎndì 昭簡帝 | Lǐ Chúnyòu 李純佑 | 1193–1206 |

| Xiāngzōng 襄宗 | Jìngmùdì 敬慕帝 | Lǐ Ānquán 李安全 | 1206–1211 |

| Shénzōng 神宗 | Yīngwéndì 英文帝 | Lǐ Zūnxū 李遵頊 | 1211–1223 |

| Xiànzōng 獻宗 | none | Lǐ Déwàng 李德旺[63][64][65] | 1223–1226 |

| Mòdì 末帝 | none | Lǐ Xiàn 李晛 | 1226–1227 |

Gallery

A clay head of the Buddha, Western Xia dynasty, 12th century

A clay head of the Buddha, Western Xia dynasty, 12th century A winged kalavinka made of grey pottery, Western Xia dynasty

A winged kalavinka made of grey pottery, Western Xia dynasty.jpg) A painting of the Buddhist manjusri, from the Yulin Caves of Gansu, China, from the Tangut-led Western Xia dynasty

A painting of the Buddhist manjusri, from the Yulin Caves of Gansu, China, from the Tangut-led Western Xia dynasty Tomb No. 3 of the Western Xia imperial tombs in Ningxia

Tomb No. 3 of the Western Xia imperial tombs in Ningxia Tangut officials

Tangut officials Tangut printing block

Tangut printing block Tangut movable type print

Tangut movable type print

See also

References

Citations

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Kuhn, Dieter (15 October 2011). The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China. p. 50. ISBN 9780674062023.

- Bowman, Rocco (2014). "Bounded Empires: Ecological and Geographic Implications in Sino- Tangut Relations, 960- 1127" (PDF). The Undergraduate Historical Journal at UC Merced. 2: 11.

- McGrath, Michael C. Frustrated Empires: The Song-Tangut Xia War of 1038-44 (150-190. ed.). In Wyatt. p. 153.

- Chinaknowledge.de Chinese History - Western Xia Empire Economy. 2000 ff. © Ulrich Theobald. Retrieved: 13 July 2017.

- Stein (1972), pp. 70–71.

- Wang, Tianshun [王天顺] (1993). Xixia zhan shi [The Battle History of Western Xia] 西夏战史. Yinchuan [银川], Ningxia ren min chu ban she [Ningxia People's Press] 宁夏人民出版社.

- Bian, Ren [边人] (2005). Xixia: xiao shi zai li shi ji yi zhong de guo du [Western Xia: the kingdom lost in historical memories] 西夏: 消逝在历史记忆中的国度. Beijing [北京], Wai wen chu ban she [Foreign Language Press] 外文出版社.

- Li, Fanwen [李范文] (2005). Xixia tong shi [Comprehensive History of Western Xia] 西夏通史. Beijing [北京] and Yinchuan [银川], Ren min chu ban she [People's Press] 人民出版社; Ningxia ren min chu ban she [Ningxia People's Press] 宁夏人民出版社.

- Zhao, Yanlong [赵彦龙] (2005). "Qian tan xi xia gong wen wen feng yu gong wen zai ti [A brief discussion on the writing style in official documents and documental carrier] 浅谈西夏公文文风与公文载体." Xibei min zu yan jiu [Northwest Nationalities Research] 西北民族研究 45(2): 78-84.

- Qin, Wenzhong [秦文忠], Zhou Haitao [周海涛] and Qin Ling [秦岭] (1998). "Xixia jun shi ti yu yu ke xue ji shu [The military sports, science and technology of West Xia] 西夏军事体育与科学技术." Ningxia da xue xue bao [Journal of Ningxia University] 宁夏大学学报 79 (2): 48-50.

- Dorje (1999), p. 444.

- Wang 2013, p. 227-228.

- Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- May, Timothy (2012). The Mongol Conquests in World History. London: Reaktion Books. p. 1211. ISBN 9781861899712.

- C. P. Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.590

- de Hartog, Leo (2004). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. New York City: I.B. Tauris. p. 59. ISBN 1860649726.

- J. Bor Mongol hiigeed Eurasiin diplomat shashtir, vol.II, p.204

- Rossabi, William (2009). Genghis Khan and the Mongol empire. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-9622178359.

- Jack Weatherford Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, p.85

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 133. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Kessler, Adam T. (2012). Song Blue and White Porcelain on the Silk Road. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 91. ISBN 9789004218598.

- Kohn, George C. (2007). Dictionary of Wars (3rd ed.). New York City: Infobase Publishing. p. 205. ISBN 9781438129167.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2012). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History (3rd ed.). Stamford, Connecticut: Cengage Learning. p. 199. ISBN 9781133606475.

- Emmons, James B. (2012). "Genghis Khan". In Li, Xiaobing (ed.). China at War: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 139. ISBN 9781598844153.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 212. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 255–256. ISBN 0674012127.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. pp. 212–213. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 213. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Hartog 2004, pg. 134

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 276. ISBN 978-1851096725.

- de Hartog, Leo (2004). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. New York City: I.B. Tauris. p. 135. ISBN 1860649726.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 219. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. pp. 219–220. ISBN 9780312366247.

- de Hartog, Leo (2004). Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World. New York City: I.B. Tauris. p. 137. ISBN 1860649726.

- Lange, Brenda (2003). Genghis Khan. New York City: Infobase Publishing. p. 71. ISBN 9780791072226.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 238. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Sinor, D.; Shimin, Geng; Kychanov, Y. I. (1998). Asimov, M. S.; Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Uighurs, the Kyrgyz and the Tangut (Eighth to the Thirteenth Century). Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century. 4. Paris: UNESCO. p. 214. ISBN 9231034677.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 256. ISBN 0674012127.

- Boland-Crewe, Tara; Lea, David, eds. (2002). The Territories of the People's Republic of China. London: Europa Publications. p. 215. ISBN 9780203403112.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Franke, Herbert and Twitchett, Denis, ed. (1995). The Cambridge History of China: Vol. VI: Alien Regimes & Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pg. 214.

- Mote 1999, pg. 256

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 256–257. ISBN 0674012127.

- Frederick W. Mote (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 256–7. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- Leffman, et al. (2005), p. 988.

- Dillon, Michael, ed. (1998). China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary. London: Curzon Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-7007-0439-6.

- Rossabi, Morris (2014). A History of China. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-57718-113-2.

- Yang, Shao-yun (2014). "Fan and Han: The Origins and Uses of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Mid-Imperial China, ca. 500-1200". In Fiaschetti, Francesca; Schneider, Julia (eds.). Political Strategies of Identity Building in Non-Han Empires in China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 24.

- Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. p. 590. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3.

- Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- Dunnell, Ruth W. (1983). Tanguts and the Tangut State of Ta Hsia. Princeton University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), page 228

- 洪, 皓. 松漠紀聞.

- Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1883). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 463–.

- Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1883. pp. 463–.

- Karl-Heinz Golzio (1984). Kings, khans, and other rulers of early Central Asia: chronological tables. In Kommission bei E.J. Brill. p. 68.

- Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 818–. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. xxiii–. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Chris Peers (31 March 2015). Genghis Khan and the Mongol War Machine. Pen and Sword. pp. 149–. ISBN 978-1-4738-5382-9.

- Mongolia Society (2002). Occasional papers. Mongolia Society. pp. 25–26.

- Luc Kwanten (1 January 1979). Imperial Nomads: A History of Central Asia, 500-1500. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8122-7750-0.

Sources

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Beckwith, Christopher I (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Dorje, Gyurme (1999), Footprint Tibet Handbook with Bhutan, Footprint Handbooks

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4

- Ferenczy, Mary (1984), The Formation of Tangut Statehood as Seen by Chinese Historiographers, Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

- Golden, Peter B. (1992), An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, OTTO HARRASSOWITZ · WIESBADEN

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David Andrew (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-46034-7.

- Guy, R. Kent (2010), Qing Governors and Their Provinces: The Evolution of Territorial Administration in China, 1644-1796, Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 9780295990187

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Kwanten, Luc (1974), Chingis Kan's Conquest of Tibet, Myth or Reality, Journal of Asian History

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Leffman, David (2005), The Rough Guide to China, Rough Guides

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Mackintosh-Smith, Tim (2014), Two Arabic Travel Books, Library of Arabic Literature

- Millward, James (2009), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mote, F. W. (1999), Imperial China: 900–1800, Harvard University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Perry, John C.; L. Smith, Bardwell (1976), Essays on T'ang Society: The Interplay of Social, Political and Economic Forces, Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-047611

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Shaban, M. A. (1979), The ʿAbbāsid Revolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29534-3

- Sima, Guang (2015), Bóyángbǎn Zīzhìtōngjiàn 54 huánghòu shīzōng 柏楊版資治通鑑54皇后失蹤, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 978-957-32-0876-1

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012), Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires), Oxford University Press

- Stein, R. A. (1972), Tibetan Civilization, London and Stanford University Press

- Twitchett, D. (1979), Cambridge History of China, Sui and T'ang China 589-906, Part I, vol.3, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-21446-7

- Wang, Zhenping (2013), Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War, University of Hawaii Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674088467.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), U OF M CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

- Xu, Elina-Qian (2005), HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PRE-DYNASTIC KHITAN, Institute for Asian and African Studies 7

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

- Yuan, Shu (2001), Bóyángbǎn Tōngjiàn jìshìběnmò 28 dìèrcìhuànguánshídài 柏楊版通鑑記事本末28第二次宦官時代, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-4273-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Western Xia. |

- 宁夏新闻网 (Ningxia News Web): 西夏研究 (Xixia Research).

- 宁夏新闻网 (Ningxia News Web): 文化频道.