History of the Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty was the ruling dynasty of China and Mongolia established by Kublai Khan and a khanate of the Mongol Empire.

History

Rise of Kublai Khan

Genghis Khan united the Mongol and Turkic tribes of the steppes and became Great Khan in 1206.[1] He and his successors expanded the Mongol Empire across Asia. Under the reign of Genghis' third son, Ögedei Khan, the Mongols destroyed the weakened Jin dynasty in 1234 and conquered most of northern China.[2] Ögedei offered his nephew Kublai a position in Xingzhou, Hebei. Kublai was unable to read Chinese, but had several Han Chinese teachers attached to him since his early years by his mother Sorghaghtani. He sought the counsel of Chinese Buddhist and Confucian advisers.[3] Möngke Khan succeeded Ögedei's son, Güyük, as Great Khan in 1251.[4] He granted his brother Kublai control over Mongol held territories in China.[5] Kublai built schools for Confucian scholars, issued paper money, revived Chinese rituals, and endorsed policies that stimulated agricultural and commercial growth.[6] He made the city of Kaiping in Inner Mongolia, later renamed Shangdu, his capital.[7]

Many Han Chinese and Khitan defected to the Mongols to fight against the Jin. Two Han Chinese leaders, Shi Tianze, Liu Heima (劉黑馬, Liu Ni),[8] and the Khitan Xiao Zhala defected and commanded the 3 Tumens in the Mongol army.[9] Liu Heima and Shi Tianze served Ogödei Khan.[10] Liu Heima and Shi Tianxiang led armies against Western Xia for the Mongols.[11] There were 4 Han Tumens and 3 Khitan Tumens, with each Tumen consisting of 10,000 troops.

Shi Tianze was a Han Chinese who lived in the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Interethnic marriage between Han and Jurchen became common at this time. His father was Shi Bingzhi (史秉直, Shih Ping-chih). Shi Bingzhi was married to a Jurchen woman (surname Na-ho) and a Han Chinese woman (surname Chang), it is unknown which of them was Shi Tianze's mother.[12] Shi Tianze was married to two Jurchen women, a Han Chinese woman, and a Korean woman, and his son Shi Gang was born to one of his Jurchen wives.[13] His Jurchen wive's surnames were Mo-nien and Na-ho, his Korean wife's surname was Li, and his Han Chinese wife's surname was Shi.[12] Shi Tianze defected to the Mongol Empire's forces upon their invasion of the Jin dynasty. His son Shi Gang married a Kerait woman, the Kerait were Mongolified Turkic people and considered as part of the "Mongol nation".[14][15]

The Yuan dynasty created a "Han Army" (漢軍) out of defected Jin troops and army of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" (新附軍).[16]

Möngke Khan commenced a military campaign against the Chinese Song dynasty in southern China.[17] The Mongol force which invaded southern China was far greater than the force they sent to invade the Middle East in 1256.[18] He died in 1259 without a successor.[19] Kublai returned from fighting the Song in 1260 when he learned that his brother, Ariq Böke, was challenging his claim to the throne.[20] Kublai convened a kurultai in the Chinese city of Kaiping that elected him Great Khan.[21] A rival kurultai in Mongolia proclaimed Ariq Böke Great Khan, beginning a civil war.[22] Kublai Khan depended on the cooperation of his Chinese subjects to ensure that his army received ample resources. He bolstered his popularity among his subjects by modeling his government on the bureaucracy of traditional Chinese dynasties and adopting the Chinese era name of Zhongtong.[23] Ariq Böke was hampered by inadequate supplies and surrendered in 1264.[24] All of the three western khanates (Golden Horde, Chagatai Khanate and Ilkhanate) became functionally autonomous, although only the Ilkhans truly recognized Kublai as Great Khan.[25][26] Civil strife had permanently divided of the Mongol Empire.[27]

The conflicts between Kublai Khan and the khanates in Central Asia led by Kaidu had lasted for a few decades, until the beginning of the 14th century, when both of them had died. Hülegü, another brother of Kublai Khan, ruled his Ilkhanate and paid homage to the Great Khan but actually established an autonomous khanate, and after Ilkhan Ghazan's enthronement in 1295, Kublai's successor Emperor Chengzong sent him a seal reading "王府定國理民之寶" in Chinese script to symbolize this.[lower-alpha 1] The four major successor khanates never came again under true one rule, and border clashes also frequently occurred among them, although Yuan dynasty's nominal supremacy was recognized by the other three after the death of Kaidu.[28]

Founding of the dynasty

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | ||||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BCE | ||||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BCE | ||||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BCE | ||||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BCE | ||||||||

| Western Zhou | ||||||||

| Eastern Zhou | ||||||||

| Spring and Autumn | ||||||||

| Warring States | ||||||||

| IMPERIAL | ||||||||

| Qin 221–207 BCE | ||||||||

| Han 202 BCE – 220 CE | ||||||||

| Western Han | ||||||||

| Xin | ||||||||

| Eastern Han | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | ||||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | ||||||||

| Jin 266–420 | ||||||||

| Western Jin | ||||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | |||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | ||||||||

| Sui 581–618 | ||||||||

| Tang 618–907 | ||||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | ||||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 |

Liao 916–1125 | |||||||

| Song 960–1279 | ||||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | |||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | Western Liao | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | ||||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | ||||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | ||||||||

| MODERN | ||||||||

| Republic of China on mainland 1912–1949 | ||||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | ||||||||

| Republic of China on Taiwan 1949–present | ||||||||

| History of Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancient period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modern period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Instability troubled the early years of Kublai Khan's reign. Li Tan, the son-in-law of a powerful official, instigated a revolt against Mongol rule in 1262. After successfully suppressing the revolt, Kublai curbed the influence of the Han Chinese advisers in his court.[29] He feared that his dependence on Chinese officials left him vulnerable to future revolts and defections to the Song.[30] Khublai's government after 1262 was a compromise between preserving Mongol interests in China and satisfying the demands of his Chinese subjects.[31] He instituted the reforms proposed by his Chinese advisers by centralizing the bureaucracy, expanding the circulation of paper money, and maintaining the traditional monopolies on salt and iron, but rejected plans to revive the Confucian imperial examinations.[32]

In 1264, he transferred his headquarters to the Daning Palace northeast of the former Jurchen capital Zhongdu. In 1266, he ordered the construction of his new capital around that site's Taiye Lake, establishing what is now the central core of Beijing. The city came to be known as Khanbaliq ("City of the Khans") and Daidu to the Turks and Mongols and Dadu (大都, "Great Capital") to the Han Chinese.[33] As early as 1264, Kublai decided to change the era name from Zhongtong (中統) to Zhiyuan (至元). With the desire to rule all of China, Kublai Khan formally claimed the Mandate of Heaven by proclaiming the new Yuan dynasty in 1271 in the traditional Chinese style.[34] This would become the first non-Han dynasty to rule all of China.

The official title of the dynasty, Da Yuan (大元, "Great Yuan"), originates from a Chinese classic text called the Commentaries on the Classic of Changes (I Ching) whose section[35] regarding Qián (乾) reads "大哉乾元" (dà zai Qián Yuán), literally translating to 'Great is Qián, the Primal', with "Qián" being the symbol of the Heaven, and the Emperor. Therefore, Yuan was the first dynasty in China to use Da (大, "Great") in its official title, as well as being the first dynasty to use a title that did not correspond to an ancient region in China.[36] In 1271, Khanbaliq officially became the capital of the Yuan dynasty. In the proclamation of the dynastic name, Kublai announced the name of the new dynasty as Yuan and claimed the succession of former Chinese dynasties from the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors to Tang dynasty.[37]

In the early 1270s, Kublai began his massive drive against the Southern Song dynasty in southern China. By 1273, Kublai had blockaded the Yangzi River with his navy and besieged Xiangyang, the last obstacle in his way to capture the rich Yangzi River basin. In 1275, a Song force of 130,000 troops under Chancellor Jia Sidao was defeated by the Yuan force. By 1276, most of the Southern Song territory had been captured by Yuan forces. In 1279, the Yuan army led by the Chinese general Zhang Hongfan had crushed the last Song resistance at the Battle of Yamen, which marked the end of the Southern Song and the onset of a united China under the Yuan. The Yuan dynasty is traditionally given credit for reuniting China after several hundred years of fragmentation following the fall of the Tang dynasty.

After the founding of the dynasty, Kublai Khan was put under pressure by many of his advisers to further expand the sphere of influence of the Yuan through the traditional Sinocentric tributary system. However, the attempts to establish such tributary relationships were rebuffed and expeditions to Japan (twice), Dai Viet (twice during Kublai's rule[lower-alpha 2]), and Java, would later meet with less success. Kublai established a puppet state in Myanmar, which caused anarchy in the area, and the Pagan Kingdom was broken up into many regions warring with each another. In order to avoid more bloodshed and conflicts with the Mongols, Annam and Champa later established nominal tributary relations with the Yuan dynasty.

Rule of Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan was seen as a martial emperor, reforming much of China and its institutions, a process that would have taken decades to complete. For example, he consolidated his rule by centralizing [38] the government of China — making himself (unlike his predecessors) an absolute monarch. He divided his empire into Branch Secretariats (行中書省), or simply provinces (行省), in addition to the regions governed by the Zhongshu Sheng or the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs. Each province governed the areas of approximately two or three modern-day Chinese provinces, and this provincial-level government structure became the model for later Ming and Qing dynasties. Kublai Khan also reformed many other governmental and economic institutions, especially the tax system. Kublai Khan sought to govern China through traditional institutions,[39] and also recognized that in order to rule China he needed to employ Han Chinese advisers and officials, though he never relied totally on Chinese advisers.[40] Yet, the Hans were discriminated against politically. Almost all important central posts were monopolized by Mongols, who also preferred employing non-Hans from other parts of the Mongol domain in those positions for which no Mongol could be found. Hans were more often employed in non-Chinese regions of the empire. In essence, society was divided into four classes in order of privilege: Mongols, Semu ("Various sorts", for example: Central Asians), Northerners, and Southerners.[41] During his lifetime, Kublai Khan built the capital of the Yuan, Khanbaliq at the site of present-day central Beijing and made Shangdu (上都, "Upper Capital", known to Marco Polo as Xanadu) the summer capital. He also improved the agriculture of China, extending the Grand Canal, highways and public granaries. Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant who served under Kublai Khan as an official, described his rule as benevolent: relieving the populace of taxes in times of hardship; building hospitals and orphanages; distributing food among the abjectly poor.

He also promoted science and religion, and strongly supported the Silk Road trade network, allowing the contacts between Chinese technologies and the western ones. It is worth mentioning that prior to meeting Marco Polo, Kublai Khan had met Niccolò Polo, Marco Polo's father and Matteo Polo. Through conversation with the two merchants, Kublai Khan developed a keen interest in the Latin world especially Christianity and sought to invite a hundred of missionaries through a letter written in Latin to the Pope so that they may convince the masses of idolators the errors of their belief. Thus Niccolò and Maffeo Polo served as ambassadors for Kublai Khan to the West. After having completed their mission of accompanying a young Mongol princess to marry the Mongol ruler Arghun, their perilous journey would end with them returning to Venice and meeting young Marco Polo of seventeen in 1271. The three returned to the East and once again met with Kublai Khan, and it was said that Marco Polo served as an emissary of Kublai Khan throughout his domain for seventeen years. Although Niccolò and Maffeo failed to bring back any missionaries with them or a letter from the Pope due to the Great Schism, they were successful in returning with oil from the lamp of God in Jerusalem.[38] Marco Polo's travels would later inspire many others like Christopher Columbus to chart the passage to the "Middle Kingdom" the realm of the East, present day China in search of wealth and splendor.

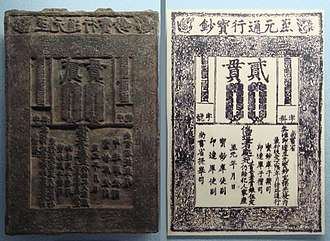

He issued paper banknotes known as Jiaochao (鈔) in 1273. Paper currency had been issued and used in China before Yuan time; by 960, the Song dynasty, short of copper for striking coins, issued the first generally circulating notes. However, during the Song dynasty, paper money was used alongside the coins. On the other hand, Yuan was the first dynasty in China to use paper currency as the predominant circulating medium. The Yuan bureaucrats made paper bills from the mulberry bark paper.

While he had claimed nominal supremacy over the rest of the Mongol Empire, his interest was clearly in China, along with the areas in its traditional Sinocentric tributary system. From the beginning of his reign, the other three khanates of the Mongol Empire became de facto independent and only one recognized him as Khagan. By the time of Kublai Khan's death in 1294, this separation has deepened, although later Yuan emperors had nominal supremacy in the west til the end of their rule in China. The temple name given for Kublai Khan is Shizu (世祖).

Early rulers after Kublai

Following the conquest of Dali in AD 1253, the former ruling Duan dynasty were appointed as governors-general, recognized as imperial officials by the Yuan, Ming, and Qing-era governments, principally in the province of Yunnan. Succession for the Yuan dynasty, however, was an intractable problem, later causing much strife and internal struggle. This emerged as early as the end of Kublai's reign. Kublai originally named his eldest son, Zhenjin as the Crown Prince — but he died before Kublai in 1285. Thus, Zhenjin's third son, with the support of his mother Kökejin and the minister Bayan, succeeded the throne and ruled as Temür Khan or Emperor Chengzong for approximately 10 years following Kublai's death (between 1294 and 1307). Temür Khan decided to maintain and continue much of the work begun by his grandfather. He also made peace with the western Mongol khanates as well as the neighboring countries such as Vietnam, which recognized his nominal suzerainty and paid tributes for a few decades. However, the corruption in the Yuan dynasty began during the reign of Temür Khan.

Külüg Khan (Emperor Wuzong) came to the throne after the death of Temür Khan. Unlike his predecessor, he did not continue Kublai's work, but largely rejected it. Most significantly he introduced a policy called "New Deals", and the central of this policy were monetary reforms. During his short reign (1307 to 1311), the government fell into financial difficulties, partly due to bad decisions made by Külüg. By the time he died, China was in severe debt and the Yuan court faced popular discontent.

The fourth Yuan emperor, Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan was a competent emperor. He was the first among the Yuan emperors who actively supported and adopted the mainstream Chinese culture after the reign of Kublai, to the discontent of some Mongol elite. He had been mentored by Li Meng, a Confucian academic. He made many reforms, including the liquidation of the Department of State Affairs (尚書省), which resulted in the execution of 5 of the highest-ranking officials. Starting in 1313 the traditional imperial examinations were reintroduced for prospective officials, testing their knowledge on significant historical works. Also, he codified much of the law, as well as publishing or translating a number of Chinese books and works.

The next emperor, Gegeen Khan, Ayurbarwada's son and successor, continued his father's policies to reform the government based on the Confucian principles, with the help of his newly appointed grand chancellor Baiju. During his reign, the Da Yuan Tong Zhi (《大元通制》, "the comprehensive institutions of the Great Yuan"), a huge collection of codes and regulations of the Yuan dynasty began by his father, was formally promulgated.

Later years of the dynasty

The last years of the Yuan dynasty were marked by struggle, famine, and bitterness among the populace. In time, Kublai Khan's successors lost all influence on other Mongol lands across Asia, while the Mongols beyond the Middle Kingdom saw them as too Chinese. Gradually, they lost influence in China as well. The reigns of the later Yuan emperors were short and were marked by intrigues and rivalries. Uninterested in administration, they were separated from both the army and the populace. China was torn by dissension and unrest; outlaws ravaged the country without interference from the weakening Yuan armies.

Regardless of the merits of his reign, Gegeen Khan (Emperor Yingzong) ruled for only two years (1321 to 1323); his rule ended in a coup at the hands of five princes. They placed Yesün Temür (or Taidingdi) on the throne, and, after an unsuccessful attempt to calm the princes, he also succumbed to regicide. Before Yesün Temür's reign, China had been relatively free from popular rebellions after the reign of Kublai. Yuan control, however, began to break down in those regions inhabited by ethnic minorities. The occurrence of these revolts and the subsequent suppression aggravated the financial difficulties of the Yuan government. The government had to adopt some measure to increase revenue such as selling offices, as well as curtailing its spending on some items.[42]

When Yesün Temür died in Shangdu in 1328, Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür was recalled to Khanbaliq by the Qipchaq commander El Temür. He was installed as the emperor (Emperor Wenzong) in Khanbaliq while Yesün Temür's son Ragibagh succeeded to the throne in Shangdu with the support of Yesün Temür's favorite retainer Dawlat Shah. Gaining support from princes and officers in Northern China and some other parts of the dynasty, Khanbaliq-based Tugh Temür eventually won the civil war against Ragibagh known as the War of the Two Capitals. Afterwards, Tugh Temür abdicated in favour of his brother Kusala who was backed by Chagatai Khan Eljigidey and announced Khanbaliq's intent to welcome him. However, Kusala suddenly died only 4 days after a banquet with Tugh Temür. He was supposedly killed with poison by El Temür, and Tugh Temür then remounted the throne. Tugh Temür also managed to send delegates to the western Mongol khanates such as Golden Horde and Ilkhanate to be accepted as the suzerain of Mongol world.[43] However, he was mainly a puppet of the powerful official El Temür during his latter three-year reign. El Temür purged pro-Kusala officials and brought power to warlords, whose despotic rule clearly marked the decline of the dynasty.

Due to the fact that the bureaucracy was dominated by El Temür, Tugh Temür is known for his cultural contribution instead. He adopted many measures honoring Confucianism and promoting Chinese cultural values. His most concrete effort to patronize Chinese learning was his founding of the Academy of the Pavilion of the Star of Literature (奎章閣學士院), first established in the spring of 1329, and was designed to undertake "a number of tasks relating to the transmission of Confucian high culture to the Mongolian imperial establishment". The academy was responsible for compiling and publishing a number of books, but its most important achievement was its compilation of a vast institutional compendium named Jingshi Dadian (《經世大典》). He supported Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism and also devoted himself in Buddhism.

After the death of Tugh Temür in 1332 and subsequently the death of Rinchinbal Khan (Emperor Ningzong) in the end of the same year, the 13-year-old Toghon Temür (Emperor Huizong), the last of the nine successors of Kublai Khan, was summoned back from Guangxi and succeeded to the throne after El Temür's death. Nevertheless, Bayan became another powerful official as El Temür was in the beginning of his long reign. As Toghun Temür grew, he came to disapprove of Bayan's autocratic rule. In 1340 he allied himself with Bayan's nephew Toqto'a, who was in discord with Bayan, and banished Bayan by coup. With the dismissal of Bayan, Toghtogha seized the power of the court. His first administration clearly exhibited fresh new spirit. He also gave a few early signs of a new and positive direction in central government. One of his successful projects was to finish the long-stalled official histories of the Liao, Jin and Song dynasties, which were eventually completed in 1345. Yet, Toghtogha resigned his office with the approval of Toghun Temür, which marked the end of his first administration, and he was not called back until 1349.

From the late 1340s onwards, people in the countryside suffered from frequent natural disasters such as droughts, floods and the resulting famines, and the government's lack of effective policy led to a loss of popular support. In 1351, the Red Turban Rebellion started and grew into a nationwide uprising. In 1354, when Toghtogha led a large army to crush the Red Turban rebels, Toghun Temür suddenly dismissed him for fear of betrayal. This resulted in Toghun Temür's restoration of power on the one hand and a rapid weakening of the central government on the other. He had no choice but to rely on local warlords' military power, and gradually lost his interest in politics and ceased to intervene in political struggles. He fled north to Shangdu from Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing) in 1368 after the approach of the forces of the Míng dynasty (1368–1644), founded by Zhu Yuanzhang in the south. He had tried to regain Khanbaliq, which eventually failed; he died in Yingchang (located in present-day Inner Mongolia) two years later (1370). Yingchang was seized by the Ming shortly after his death. Some royal family members still lived in Henan today.[44]

The Prince of Liang, Basalawarmi established a separate pocket of resistance to the Ming in Yunnan and Guizhou, but his forces were decisively defeated by the Ming in 1381. By 1387 the remaining Yuan forces in Manchuria under Naghachu had also surrendered to the Ming dynasty.

End of Yuan rule

The Yuan remnants retreated to Mongolia after the fall of Yingchang to the Ming in 1370, where the name Great Yuan (大元) was formally carried on, and is known as the Northern Yuan dynasty. According to Chinese political orthodoxy, there could be only one legitimate dynasty whose rulers were blessed by Heaven to rule as Emperor of China (see Mandate of Heaven), and so the Ming and the Northern Yuan denied each other's legitimacy as emperors of China, although the Ming did consider the previous Yuan which it had succeeded to be a legitimate dynasty. Historians generally regard Ming dynasty rulers as the legitimate emperors of China after the Yuan dynasty, though Norther Yuan rulers also claimed to rule over China, and continued to resist the Ming under the name "Yuan" or "Northern Yuan".[lower-alpha 3]

The Ming army pursued the ex-Yuan Mongol forces into Mongolia in 1372, but were defeated by the latter under Biligtü Khan Ayushiridara and his general Köke Temür. They tried again in 1380, ultimately winning a decisive victory over the Northern Yuan in 1388. About 70,000 Mongols were taken prisoner, and Karakorum (the Northern Yuan capital) was sacked.[45] Eight years later, the Northern Yuan throne was taken over by Biligtü Khan Ayushiridara, a descendant of Ariq Böke, instead of the descendants of Kublai Khan. The following centuries saw a succession of Genghisid rulers, many of whom were mere figureheads put on the throne by those warlords who happened to be the most powerful. Periods of conflict with the Ming dynasty intermingled with periods of peaceful relations with border trade. In 1402, Örüg Temür Khan (Guilichi) abolished the name Great Yuan; he was however defeated by Öljei Temür Khan (Bunyashiri), protege of Tamerlane (Timur Barulas) in 1403. A few decades later the new khan Batumongke (1464–1517/43) took the title Dayan meaning "Da Yuan" or "Great Yuan".[46] and reunited the Mongols. His successors continued to rule until the submission to the Qing dynasty in the 17th century.

References

Notes

- The seal, in Chinese script, reads "Seal certifying the authority of his Royal Highness to establish a country and govern its people". Vatican Archives.

- An earlier expedition was launched in 1258, before they moved north to attack the Song.

- The Northern Yuan rulers had also buttressed their claim on China at least up to the 15th century, who held tenaciously to the title of Emperor (or Great Khan) of the Great Yuan (Dai Yuwan Khaan, or 大元可汗). For more information regarding the use of the name Yuan among Mongols and the memory of it in later ages, see Morikawa 2008.

Citations

- Ebrey 2010, p. 169.

- Ebrey 2010, pp. 169–170.

- Rossabi 1994, p. 415.

- Allsen 1994, p. 392.

- Allsen 1994, p. 394.

- Rossabi 1994, p. 418.

- Rossabi 2012, p. 65.

- Collectif 2002, p. 147.

- May, Timothy Michael (2004). The Mechanics of Conquest and Governance: The Rise and Expansion of the Mongol Empire, 1185-1265 (Dissertation). University of Wisconsin-Madison. p. 50.

- Schram 1987, p. 130.

- eds. Seaman, Marks 1991, p. 175.

- ed. de Rachewiltz 1993, p. 41.

- Kinoshita 2013, p. 47.

- Watt, James C. Y. (2010). The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 14. ISBN 9781588394026.

- Kinoshita 2013, p. 47.

- Hucker 1985, p.66.

- Allsen 1994, p. 410.

- Smith, Jr. 1998, p. 54.

- Allsen 1994, p. 411.

- Rossabi 1994, p. 422.

- Rossabi 1988, p. 51.

- Rossabi 1988, p. 53.

- Rossabi 1994, p. 423–424.

- Morgan 2007, p. 104.

- Rossabi 1988, p. 62.

- Allsen 1994, p. 413.

- Allsen 2001, p. 24.

- H.H.Howorth-History of the Mongols, vol.II p.288

- Rossabi 1994, p. 426.

- Rossabi 1988, p. 66.

- Rossabi 1994, p. 427.

- Rossabi 1988, pp. 70–71.

- Rossabi 1989, p. 131.

- Mote 1994, p. 624.

- 《易·乾·彖傳》. Commentaries on the Classic of Changes (《易傳》).

《彖》曰:大哉乾元,萬物資始,乃統天。

- Zhu Guozhen. Yong Zhuang Xiaopin 涌幢小品. 2.

- Kublai Khan. 建國號詔 [Edict to Establish the Name of the State]. Yuan Dianzhang 元典章.

- Wood, Frances (2010) [1995]. Did Marco Polo go to China?. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-8133-8999-8.

- Rossabi 1989, p. 56.

- Rossabi 1989, p. 115.

- Mote 1994, p. 631.

- Hsiao 1994, p. 551.

- Hsiao 1994, p. 550.

- 成吉思汗直系后裔现身河南巨幅家谱为证(组图) [Genghis Khan’s immediate descendants appear in Henan’s huge family tree, with evidence (Photos)]. news.xinmin.cn. 2007-02-06.

- Prawdin, Michael (1940). The Mongol Empire, its Rise and Legacy. London: G. Allen and Unwin. p. 389 – via archive.org.

- Morikawa 2008.

Bibliography

- Allsen, Thomas (2001). Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80335-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Allsen, Thomas (1994). "The rise of the Mongolian empire and Mongolian rule in north China". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke (sinologist); John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 321–413. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chan, Hok-lam; de Bary, W.T., eds. (1982). Yuan Thought: Chinese Thought and Religion Under the Mongols. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05324-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cotterell, Arthur (2007). The Imperial Capitals of China - An Inside View of the Celestial Empire. London: Pimlico. ISBN 9781845950095.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dardess, John (1994). "Shun-ti and the end of Yuan rule in China". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke (sinologist); John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 561–586. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010) [1996]. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Endicott-West, Elizabeth (1994). "The Yuan government and society". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke (sinologist); John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 587–615. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guzman, Gregory G. (1988). "Were the Barbarians a Negative or Positive Factor in Ancient and Medieval History?". The Historian. Blackwell Publishing. 50 (4): 558–571. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1988.tb00759.x.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hsiao, Ch'i-Ch'ing (1994). "Mid-Yuan Politics". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke (sinologist); John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 490–560. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langlois, John D. (1981). China Under Mongol Rules. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-10110-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paludan, Ann (1998). Chronicle of the China Emperors. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05090-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, David (1982). "Who Ran the Mongol Empire?". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. 114 (1): 124–136. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00159179.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morgan, David (2007). The Mongols. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3539-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morikawa, Tetsuo (2008). 大元の記憶 [Memory of the Dai Yuan ulus (the Great Yuan dynasty)] (PDF). Bulletin of the Graduate School of Social and Cultural Studies, Kyushu University. 14: 65–81.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-44515-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (hardcover); ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7 (paperback).

- Mote, Frederick W. (1994). "Chinese society under Mongol rule, 1215-1368". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke (sinologist); John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 616–664. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rossabi, Morris (1988). Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06740-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rossabi, Morris (1994). "The reign of Khubilai Khan". In Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke (sinologist); John King Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 710–1368. Cambridge University Press. pp. 414–489. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rossabi, Morris (2012). The Mongols: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-984089-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, John Joseph (2001) [1971]. The History of the Mongol Conquests. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-812-21766-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Jr., John Masson (Jan–Mar 1998). "Review: Nomads on Ponies vs. Slaves on Horses". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 54–62. doi:10.2307/606298. JSTOR 606298.