Quan Tangshi

Quan Tangshi (Complete Tang Poems), commissioned in 1705 at the direction and published under the name of the Qing dynasty Kangxi Emperor, is the largest collection of Tang poetry, containing some 49,000 lyric poems by more than twenty-two hundred poets.[1] The Quan Tangshi is the major reservoir of surviving Tang dynasty poems, from which the pre-eminent shorter anthology, Three Hundred Tang Poems, is largely drawn.

| Quan Tangshi | |

|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 全唐詩 |

| Simplified Chinese | 全唐诗 |

| Literal meaning | Complete (collection of) Tang shi poetry |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Quán Tángshī |

| Wade–Giles | Ch'üan2 T'ang2-shih1 or Ch'üan T'ang shih |

| Reference abbreviations:

QTS (for Pinyin), ChTS (for other) Alternate Chinese name = 御定全唐詩 | |

Compilation

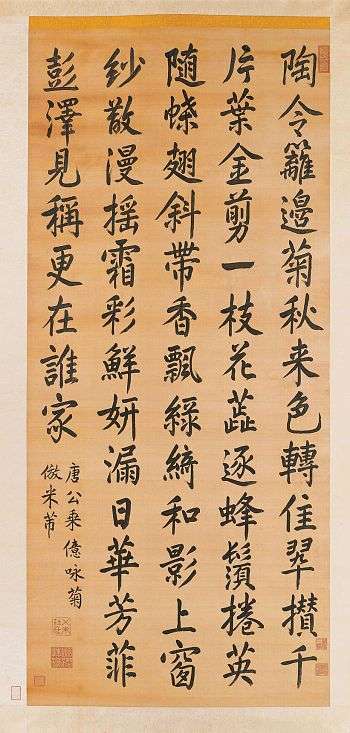

In 1705, the Kangxi Emperor issued an edict to Cao Yin, a trusted imperial bondservant, official, and a literary figure in his own right. He commanded Cao to compile and publish all the surviving shi (lyric poems) of the Tang, inaugurating the first of the great literary projects for which the Manchu dynasty became famous. The emperor also appointed nine scholars of the Hanlin Academy to oversee the collation of the texts. The team compared texts from various libraries as well as checking into private collections. Cao trained calligraphers in a common style of writing before carving the wood blocks for printing. The work was finished in the remarkably short time, though Cao felt called upon to apologize to the emperor for the delay. More than one hundred craftsmen worked on the printing, for which paper was specially procured. Although the emperor decided that Cao's name would be the first to be listed in the book itself, in the catalog to the Four Collections of Imperial Treasures, the Complete Tang Poems are listed as an "Imperial Compilation" (yuding) that is, of the emperor.[2]

Significance and contents

Although the Quan Tangshi (QTS) is the largest compilation of Tang poems, it is neither completely reliable nor complete. The work was done in some haste, and the editors did not justify or even indicate their own choices of texts or variant readings (other than perhaps by a first choice and list of variants: definitely weak by modern academic standards). Many additional poems and variant texts were discovered in the early 20th century in the cave library at Dunhuang, for instance, and the compilers ignored or could not find others. In the case of some major poets, there were better texts in individually edited volumes. Many are listed in Tang dynasty catalogs but did not survive the destruction of the imperial libraries.[3]

The poems are arranged in sections, for instance, those by emperors or consorts and 乐府 Yuefu (Music Bureau-style poems). Seven hundred and fifty-four sections, the largest number of sections, are arranged by author (with brief biography). Others are arranged by form or subject, such as women (five sections), monks, priests, spirits, ghosts, dreams, prophecy, proverbs, mystery, rumor, and drinking.[4]

Notes

- Yu (1994), p. 105.

- Spence (1966), p. 157-164.

- Kroll (2001), p. 279-280.

- Peng (1960).

Cited works

- Kroll, Paul (2001), "Poetry of the T'ang dynasty", in Mair, Victor (ed.), The Columbia History of Chinese Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 274–313, ISBN 0231109849CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1966). Ts'ao Yin and the K'ang-Hsi Emperor: Bondservant and Master. New Haven: Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peng, Dingqiu 彭定球 (1960). 全唐詩 (Quan Tang Shi). Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Typeset punctuated edition in 25 volumes, but commentaries are not included.

- Yu, Pauline (1994), "The Chinese Poetic Canon and its Boundaries", in Hay, John (ed.), Boundaries in China, London: Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-0-948462-38-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

External links

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |