Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank

The banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank (Traditional Chinese: 大清銀行兌換券), known as the banknotes of the Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue (Traditional Chinese: 大清戶部銀行兌換券) from 1905 to 1908, were intended to become the main form of paper money in the Qing currency system. These banknotes were issued by the Ta-Ching Government Bank, a national bank established to serve as the central bank of the Qing dynasty. The Ta-Ching Government Bank had branches throughout China and many of its branches outside of its headquarters in Beijing also issued banknotes.

.jpg)

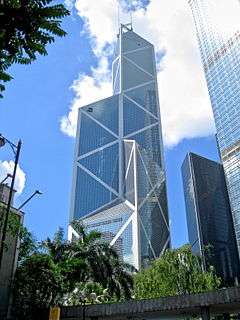

These banknotes were stipulated to become the only legal tender paper money in China in 1910, but due to the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 the Chinese currency system reverted back to its original chaotic state during the early Republican era and the Ta-Ching Government Bank would be renamed to the Bank of China in 1912, which would continue to produce banknotes in Mainland China until 1942 and its Hong Kong branch is still one of the official note-issuing banks for the banknotes of the Hong Kong dollar today.

History

The Ta-Ching Government Bank was the first official financial institution in the history of China to fulfill the functions of a central bank.

Background and banknotes of the Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue

During the transition from Ming to Qing the Manchu government issued banknotes to finance its expensive military campaigns, but following their conquest of China they abolished these banknotes.[1][2][3][4] Under the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor the Da-Qing Baochao (大清寶鈔) copper-alloy cash coins-based banknotes and Hubu Guanpiao (戶部官票) silver tael-based banknotes were introduced in response to the Taiping Rebellion,[5][1][6][7] but these banknotes would suffer severe inflation due to mismanagement and were eventually abolished causing the Chinese populace to distrust government-issued paper money once again,[1] though private banknotes would continue to be trusted and to circulate.[1]

Following the opening up of many treaty port cities of China after its defeat during the First Opium War during the 1840s, a large number of major foreign banks entered China and started issuing their own banknotes there for local circulation.[8] During this same era provincial governments started setting up their own official banks to enhance their financial resources. The boom of financial institutions during this era meant that various forms of paper money, private banknotes, foreign banknotes, and many different kinds of local coinages circulated concurrently creating a very chaotic Chinese currency system.[9] During the later part of the Qing dynasty era there was a discussion on whether or not the imperial Chinese government would have to establish a national bank which it finally did in 1905. Peng Shu (彭述) stated before the introduction of new banknotes that the national bank would have to keep sufficient reserves in "touchable" money (現金) at all times. The large number of private notes that were being produced all over the empire was to be restricted by introducing a stamp duty (印花稅). The reformer Liang Qichao campaigned for the government of the Qing dynasty to emulate the Western world and Japan by embracing the gold standard, unify refractory the currencies of China, and issue government-backed banknotes with a ⅓ metallic reserve.[10] In order to unify the national currency system, in 1905, the government of the Qing dynasty established the "Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue" (大清戶部銀行) in Beijing, becoming the earliest officially opened national bank in China.[11] The newly established national bank had a dual nature of being both a central bank and a commercial bank.[12] The production of the banknotes was entrusted to the prints of the Beiyang Newspaper (北洋報局) in Northern China. In 1906 the government of the Qing dynasty sent students to Japan to be educated about modern printing techniques, with the aim to have the Shanghai Commercial Press (上海商務印書館) print the cheques of the Ministry's Bank.[1]

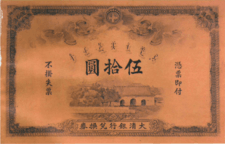

The Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue were still issuing two different types of banknotes, one series was denominated in "tael" (兩), these were known as the Yinliang Piao (銀兩票) and had the denominations of 1 tael, 5 taels, 10 taels, 50 taels, and 100 taels. The other series was denominated in "yuan" and were known as Yinyuan Piao (銀元票) and were issued in the denominations of 1 yuan, 5 yuan, 10 yuan, 50 yuan, and 100 yuan.[13]

Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank

In the year 1906, the government of the Qing dynasty was reformed and in the year 1908 the Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue changed its name to the Ta-Ching Government Bank (大清銀行) and the inscriptions of the banknotes issued by it had to be changed to reflect its new name. The banknotes issued before the name change were all printed by the Beiyang Newspaper.[14] Because there is no advanced engraving technology for banknotes in China at the time and the banknotes that were printed by the Beiyang Newspaper's commercial press were both expensive to make and easy to imitate, the government of the Qing dynasty had later commissioned the American Bank Note Company to print new banknotes for the Ta-Ching Government Bank.[15]

The banknotes produced by the Ta-Ching Government Bank printed by the American Bank Note Company featured an image of Li Hongzhang on their observe sides and were subsequently known as "Li Hongzhang notes" (李鴻章像券) to the Chinese public. However, due to the turbulent situation that arose after the death of the Guangxu Emperor and the miscommunications the "Li Hongzhang notes" were printed in various forms and the circulation was chaotic.[12]

During this period, several employees of the Ta-Ching Government Bank were sent to Japan to study modern printing technology and after these people returned to China, they would propose to the imperial court to adopt the Japanese method of copper engraving and some trial banknotes were made, but the proposition was ultimately not adopted by the government of the Qing dynasty.[16]

Following the Chinese tradition of issuing new money in a new reign, the Xuantong administration had the design of the official Ta-Ching Government Bank paper notes somewhat changed to herald in the new emperor.[1] The new design was inspired by the designs of the banknotes of the United States dollar of this era.[1]

In the year 1910, the government of the Qing dynasty issued a new law to solve the chaotic currency situation of China at the time, this law made the banknotes issued by the Ta-Ching Government Bank the only legal tender paper money in China. The law further stipulated that only the Ta-Ching Government Bank can issue paper money and that its banknotes can be used for all payment activities and financial transactions across the country. The government of the Qing dynasty hired the American sculptor L. J. Hatch and several American technicians to train the banknote printing staff and they were set out to design a new version of Ta-Ching Government Bank banknotes.[17] The obverse of these newly designed banknotes featured the face of Zaifeng, Prince Chun and were popularly known as "Ta-Ching Dragon banknotes" (大清龍鈔) because they incorporated a Chinese dragon in their designs. The Ta-Ching Government Bank had commissioned eighth trial banknotes based on these designs, they were in the denominations of 1 yuan, 5 yuan, 10 yuan, and 100 yuan.[18] Ultimately, the trial notes all featured a black obverse side and their reverse sides in different colours with the 1 yuan being green, the 5 yuan being purple, the 10 yuan being blue, and the 100 yuan being yellow, they were all printed by a branch of the Ta-Ching Government Bank. Printing of the "Ta-Ching Dragon banknotes" began on 1 March, 1911. China also became one of the few countries in the world to adopt the technique of steel engraving.[19] These banknotes did not see circulation as in 1911 the Xinhai Revolution broke out which overthrew the Qing dynasty and only a handful of trial banknotes were ever printed.[12][17][20]

At the eve of the Xinhai Revolution, there were 5,400,000 tael worth of Yinliang banknotes circulating in China, and 12,400,000 yuan in Yinyuan banknotes.[1]

Aftermath

_01.jpg)

In the year 1912, the Republic of China was established, and the Ta-Ching Government Bank had changed its name to the "Bank of China" (中國銀行). In order to alleviate the financial crisis, a large number of "Li Hongzhang notes" were overstamped and changed to "Bank of China notes" (中國銀行兌換券) for circulation.[17]

The Bank of China would continue producing Chinese banknotes until 1942.[21][22] After the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949, the Bank of China effectively split into two operations. Part of the bank relocated to Taiwan with the Kuomintang (KMT) government, and was privatised in 1971 to become the International Commercial Bank of China (中國國際商業銀行). In 2002, it merged with Chiao Tung Bank (交通銀行) to become the Mega International Commercial Bank. The Mainland operation is the current entity known as the Bank of China. The Hong Kong branch of the Bank of China still issues its own banknotes in Hong Kong today.[23][24]

List of banknotes

1906

| Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue (1906 issue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Main Color | Description | Date of issue | ||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

1 dollar | 1906 | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

5 dollars | 1906 | |||

_02.jpg) |

_01.jpg) |

10 dollars | 1906 | |||

|

50 dollars | 1906 | ||||

1907

| Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Bank of the Ministry of Revenue (1907 issue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Main Color | Description | Date of issue | ||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

1 dollar | 1907 | |||

_-_Ta-Ching_Government_Bank_(%E5%A4%A7%E6%B8%85%E9%8A%80%E8%A1%8C%E5%85%8C%E6%8F%9B%E5%88%B8%E6%94%B9%E5%A4%A7%E6%BC%A2%E9%8A%80%E8%A1%8C%E6%9A%AB%E8%A1%8C%E8%BB%8D%E7%94%A8%E6%89%8B%E7%A5%A8)_issue_(%E5%85%89%E7%B7%92%E4%B8%89%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%89%E5%B9%B4_-_1907%E5%B9%B4)_KKNews_-_Obverse.jpg) |

_-_Ta-Ching_Government_Bank_(%E5%A4%A7%E6%B8%85%E9%8A%80%E8%A1%8C%E5%85%8C%E6%8F%9B%E5%88%B8%E6%94%B9%E5%A4%A7%E6%BC%A2%E9%8A%80%E8%A1%8C%E6%9A%AB%E8%A1%8C%E8%BB%8D%E7%94%A8%E6%89%8B%E7%A5%A8)_issue_(%E5%85%89%E7%B7%92%E4%B8%89%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%89%E5%B9%B4_-_1907%E5%B9%B4)_KKNews_-_Reverse.jpg) |

5 dollars | 1907 | |||

|

|

10 dollars | 1907 | |||

1908

| Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank (1908 issue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Main Color | Description | Date of issue | ||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

10 dollars | 1908 | |||

1909

| Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank (1909 issue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Main Color | Description | Date of issue | ||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

1 dollar | 1909 | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

5 dollars | 1909 | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

10 dollars | 1909 | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

100 dollars | 1909 | |||

1910

| Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank (1910 issue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Main Color | Description | Date of issue | ||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||

_Colnect_01.jpg) |

_Colnect_02.jpg) |

1 dollar | 1910 | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

5 dollars | 1910 | |||

_Colnect_01.jpg) |

_Colnect_02.jpg) |

10 dollars | 1910 | |||

_01.jpg) |

_02.jpg) |

100 dollars | 1910 | |||

1911

| Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank (1911 issue) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Main Color | Description | Date of issue | ||

| Obverse | Reverse | Obverse | Reverse | |||

.jpg) |

1 tael | 1911 | ||||

.jpg) |

2 taels | 1911 | ||||

References

- Ulrich Theobald (13 April 2016). "Qing Period Paper Money". Chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Yang Lien-sheng (1954) Money and credit in China: a short history. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, p. 68.

- Shi Yufu (石毓符) (1984) Zhongguo huobi jinrong shilüe (中國貨幣金融史略). Tianjin renmin chubanshe, Tianjin, pp. 109–11. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- Rajeev Prasad (23 November 2012). "Did you know Series (14): Shanghai Museum :A treasure trove of ancient Chinese , Indian and Islamic coinage". Exclusivecoins.Blogspot.com. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- Jerome Ch'ên (October 1958). "The Hsien-Fêng Inflation (Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009)". SOAS University of London. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- John E. Sandrock (1997). "IMPERIAL CHINESE CURRENCY OF THE TAI'PING REBELLION - Part II - CH'ING DYNASTY COPPER CASH NOTES by John E. Sandrock" (PDF). The Currency Collector. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- John E. Sandrock (1997). "THE FOREIGN BANKS IN CHINA, PART I - EARLY IMPERIAL ISSUES (1850-1900) by John E. Sandrock - The Opening of China to the Outside World" (PDF). The Currency Collector. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Niv Horesh (2019). The Monetary System of China under the Qing Dynasty. Springer Link. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-0622-7_54-1. ISBN 978-981-10-0622-7.

- 鹤龄. 大清银行第一套钞票 [J]. 会计之友, 2004(2):72-72. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- Hou Houji (侯厚吉), Wu Qijing (吴其敬) (1982) Zhongguo jindai jingji sixiang shigao (中國近代經濟思想史稿). Heilongjiang renminchubanshe, Harbin, vol. 3, pp. 322–339. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- Unlisted (17 April 2008). "A Brief History of the Bank of China". China-Briefing. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "清末民初的大清银行兑换券" (in Chinese). 新浪. 2016-12-05. Retrieved 2017-03-15.

- Bruce, Colin - Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, Volume 1, Iola, Wisconsin 2005, Krause Publications.

- 王金华, 张芳. 户部银行时期的大清银行兑换券[J]. 中国钱币, 2005(4):32-33. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- 孙浩. 美钞公司档案中李鸿章像大清银行兑换券承印始末[J]. 中国钱币, 2013(6):9-12. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- 高桂云. “大清门”伍拾圆兑换券铜质凹印票版浅议[J]. 钱币博览, 2006(4):30-31. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- 顾慧. 一套没有完成社会使命的大清纸币——大清银行兑换券的诞生始末[J]. 艺术市场, 2009(4):82-83. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- 毕凤鹏, 李茂, 杨若龄,等. 大清银行兑换券试色样票始末[J]. 中国钱币, 1992(4):19-22. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- 添寿. 我国首批机印钞票诞生始末[J]. 安徽钱币, 2006(1):34-35. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- 王志东 (2013-07-14). "溥仪"阿玛"现身钞票上 溥仪因稚气未脱未登票面" (in Chinese). 中新网.

- Noah Elbot (2019). "China's 1935 Currency Reform: A Nascent Success Cut Short By Noah Elbot". Duke East Asia Nexus (Duke University). Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Chang, H.: The Silver Dollars and Taels of China. Hong Kong, 1981 (158 pp. illus.). Including Subsidiary Notes on “The Silver Dollars and Taels of China” Hong Kong, 1982 (40 pp. illus.). OCLC 863439444.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Enoch Yiuenoch.yiu@scmp.com (2 September 2019). "Cantonese opera features on new HK$100 banknotes launched by HSBC, Standard Chartered and Bank of China (Hong Kong) on Tuesday". Yahoo! Finance (Verizon). Retrieved 5 January 2020.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banknotes of the Ta-Ching Government Bank. |

_-_%E9%99%B3%E5%AE%97%E5%B6%BD.jpg)

_-_Treasury_of_the_Ming_Dynasty_(1368-1399)_01.jpg)

_01.jpg)