Military of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty (1636–1912) was established by conquest and maintained by armed force. The founding emperors personally organized and led the armies, and the continued cultural and political legitimacy of the dynasty depended on the ability to defend the country from invasion and expand its territory. Therefore, military institutions, leadership, and finance were fundamental to the dynasty's initial success and ultimate decay. The early military system centered on the Eight Banners, a hybrid institution that also played social, economic, and political roles.[1] The Banner system was developed on an informal basis as early as 1601, and formally established in 1615 by Jurchen leader Nurhaci (1559–1626), the retrospectively recognized founder of the Qing. His son Hong Taiji (1592–1643), who renamed the Jurchens "Manchus," created eight Mongol banners to mirror the Manchu ones and eight "Han-martial" (漢軍; Hànjūn) banners manned by Chinese who surrendered to the Qing before the full-fledged conquest of China proper began in 1644. After 1644, the Ming Chinese troops that surrendered to the Qing were integrated into the Green Standard Army, a corps that eventually outnumbered the Banners by three to one.

The use of gunpowder during the High Qing can compete with the three gunpowder empires in western Asia.[2] Manchu imperial princes led the Banners in defeating the Ming armies, but after lasting peace was established starting in 1683, both the Banners and the Green Standard Armies started to lose their efficiency. Garrisoned in cities, soldiers had few occasions to drill. The Qing nonetheless used superior armament and logistics to expand deeply into Central Asia, defeat the Dzungar Mongols in 1759, and complete their conquest of Xinjiang. Despite the dynasty's pride in the Ten Great Campaigns of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796), the Qing armies became largely ineffective by the end of the 18th century. It took almost ten years and huge financial waste to defeat the badly equipped White Lotus Rebellion (1795–1804), partly by legitimizing militias led by local Han Chinese elites. The Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), a large-scale uprising that started in southern China, marched within miles of Beijing in 1853. The Qing court was forced to let its Han Chinese governors-general, first led by Zeng Guofan, raise regional armies. This new type of army and leadership defeated the rebels but signaled the end of Manchu dominance of the military establishment.

The military technology of the European Industrial Revolution made China's armament and military rapidly obsolete. In 1860 British and French forces in the Second Opium War captured Beijing and sacked the Summer Palace. The shaken court attempted to modernize its military and industrial institutions by buying European technology. This Self-Strengthening Movement established shipyards (notably the Jiangnan Arsenal and the Foochow Arsenal) and bought modern guns and battleships in Europe. The Qing navy became the largest in East Asia. But organization and logistics were inadequate, officer training was deficient, and corruption widespread. The Beiyang Fleet was virtually destroyed and the modernized ground forces defeated in the 1895 First Sino-Japanese War. The Qing created a New Army, but could not prevent the Eight Nation Alliance from invading China to put down the Boxer Uprising in 1900. The revolt of a New Army corps in 1911 led to the fall of the dynasty.

Eight Banners system

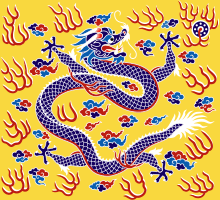

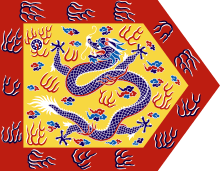

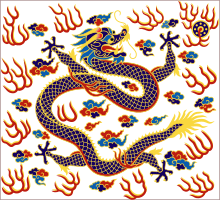

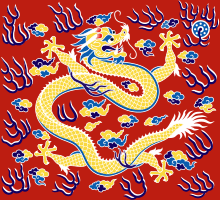

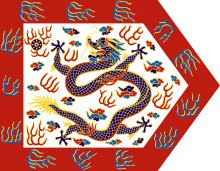

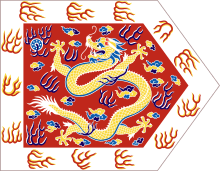

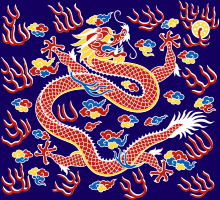

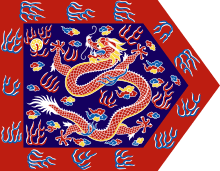

One of the keys to Nurhaci's successful unification of Jurchen tribes and his challenge to the Ming dynasty in the early seventeenth century was the formation of the Eight Banners, a uniquely Manchu institution that was militarily efficient, but also played economic, social, and political roles.[3] As early as 1601 and possibly a few years earlier, Nurhaci made his soldiers and their families register into permanent companies known as niru, the same name as the smaller hunting parties in which Jurchen men traditionally joined to practice military operations and wage war.[4] Sometime before 1607, these companies were themselves grouped into larger units called gūsa, or "banners," differentiated by colors: yellow, white, red, and blue.[5] In 1615 a red border was added to each flag (except for the red banner, to which a white border was added) to form a total of eight banners that Jurchen troops carried into battles.[5] The banner system allowed Nurhaci's new state to absorb defeated Jurchen tribes simply by adding companies; this integration in turn helped to reorganize Jurchen society beyond petty clan affiliations.[6]

As Qing power expanded north of the Great Wall, the Banner system kept expanding too. Soon after defeating the Chahar Mongols with the help of other Mongol tribes in 1635, Nurhaci's son and successor Hong Taiji incorporated his new Mongol subjects and allies into the Mongol Eight Banners, which ran parallel to the original Manchu banners.[7] Hong Taiji was more prudent in integrating Chinese troops.[8] In 1629, he first created a "Chinese army" (Manchu: ᠨᡳᡴᠠᠨ

ᠴᠣᠣᡥᠠ nikan cooha; Chinese: 漢軍; pinyin: Hànjūn) of about 3000 men.[9] In 1631 these Chinese units absorbed men that could build and operate European-style cannon, and were therefore renamed "Heavy Troops" (M.: ujen cooha; Chinese: 重軍; pinyin: Zhòngjūn).[10] By 1633 they counted about 20 companies and 4,500 men fighting under black standards.[10] These Chinese companies were grouped into two banners in 1637, four in 1639, and finally eight banners in 1642.[7] These "Hanjun" banners are known as the "Chinese" or "Chinese-martial" banners.[11]

Select groups of Han Chinese bannermen were mass transferred into Manchu Banners by the Qing, changing their ethnicity from Han Chinese to Manchu. Han Chinese bannermen of Tai Nikan 台尼堪 (watchpost Chinese) and Fusi Nikan 抚顺尼堪 (Fushun Chinese)[12] backgrounds into the Manchu banners in 1740 by order of the Qing Qianlong emperor.[13] It was between 1618-1629 when the Han Chinese from Liaodong who later became the Fushun Nikan and Tai Nikan defected to the Jurchens (Manchus).[14] These Han Chinese origin Manchu clans continue to use their original Han surnames and are marked as of Han origin on Qing lists of Manchu clans. Manchu families adopted Han Chinese sons from families of bondservant Booi Aha (baoyi) origin and they served in Manchu company registers as detached household Manchus and the Qing imperial court found this out in 1729. Manchu Bannermen who needed money helped falsify registration for Han Chinese servants being adopted into the Manchu banners and Manchu families who lacked sons were allowed to adopt their servant's sons or servants themselves.[15] The Manchu families were paid to adopt Han Chinese sons from bondservant families by those families. The Qing Imperial Guard captain Batu was furious at the Manchus who adopted Han Chinese as their sons from slave and bondservant families in exchange for money and expressed his displeasure at them adopting Han Chinese instead of other Manchus.[16] These Han Chinese who infiltrated the Manchu Banners by adoption were known as "secondary-status bannermen" and "false Manchus" or "separate-register Manchus", and there were eventually so many of these Han Chinese that they took over military positions in the Banners which should have been reserved for Manchus. Han Chinese foster-son and separate register bannermen made up 800 out of 1,600 soldiers of the Mongol Banners and Manchu Banners of Hangzhou in 1740 which was nearly 50%. Han Chinese foster-son made up 220 out of 1,600 unsalaried troops at Jingzhou in 1747 and an assortment of Han Chinese separate-register, Mongol, and Manchu bannermen were the remainder. Han Chinese secondary status bannermen made up 180 of 3,600 troop households in Ningxia while Han Chinese separate registers made up 380 out of 2,700 Manchu soldiers in Liangzhou. The result of these Han Chinese fake Manchus taking up military positions resulted in many legitimate Manchus being deprived of their rightful positions as soldiers in the Banner armies, resulting in the real Manchus unable to receive their salaries as Han Chinese infiltrators in the banners stole their social and economic status and rights. These Han Chinese infiltrators were said to be good military troops and their skills at marching and archery were up to par so that the Zhapu lieutenant general couldn't differentiate them from true Manchus in terms of military skills.[17] Manchu Banners contained a lot of "false Manchus" who were from Han Chinese civilian families but were adopted by Manchu bannermen after the Yongzheng reign. The Jingkou and Jiangning Mongol banners and Manchu Banners had 1,795 adopted Han Chinese and the Beijing Mongol Banners and Manchu Banners had 2,400 adopted Han Chinese in statistics taken from the 1821 census. Despite Qing attempts to differentiate adopted Han Chinese from normal Manchu bannermen the differences between them became hazy.[18] These adopted Han Chinese bondservants who managed to get themselves onto Manchu banner roles were called kaihu ren (開戶人) in Chinese and dangse faksalaha urse in Manchu. Normal Manchus were called jingkini Manjusa.

The Manchus sent Han Bannermen to fight against Koxinga's Ming loyalists in Fujian.[19] The Qing carried out a seaban forcing people to evacuated the coast in order to deprive Koxinga's Ming loyalists of resources, this has led to a myth that it was because Manchus were "afraid of water". In Fujian, it was traitors Northern Han Bannermen who were the ones carrying out the fighting for the Qing and this disproved the entirely irrelevant claim that alleged fear of the water on part of the Manchus had to do with the coastal evacuation and seaban.[20] A poem shows northern Han bannermen referring to the Tanka people living at the coast and rivers of Southern Fujian as "barbarians".[21]

The banners in their order of precedence were as follows: yellow, bordered yellow, white, red, bordered white, bordered red, blue, and bordered blue. The yellow, bordered yellow, and white banners were collectively known as the "Upper Three Banners" (Chinese: 上三旗; pinyin: shàng sān qí) and were under the direct command of the emperor. Only Manchus belonging to the Upper Three Banners, and selected Han Chinese who had passed the highest level of martial exams were qualified to serve as the emperor's personal bodyguards. The remaining Banners were known as the "Lower Five Banners" (Chinese: 下五旗; pinyin: xià wǔ qí) and were commanded by hereditary Manchu princes descended from Nurhachi's immediate family, known informally as the "Iron Cap Princes." In Nurhaci's era and the early Hong Taiij era, these princes formed the ruling council of the Manchu nation as well as high command of the army.

- Upper Three Banners

- Lower Five Banners

Green Standard Army

After capturing Beijing in 1644 and as the Qing rapidly gained control of large tracts of former Ming territory, the relatively small Banner armies were further augmented by remnants of Ming forces that surrendered to the Qing. Some of these troops were first accepted into the Chinese-martial banners, but after 1645 they were integrated a new military unit called the Green Standard Army, named after the color of their battle pennants.[22] The Qing created Chinese armies in the regions it conquered. Green Standard armies were created in Shanxi, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Jiangnan in 1645, in Fujian in 1650, in Lianguang (Guangdong and Guangxi) in 1651, in Guizhou in 1658, and in Yunnan in 1659.[23] They maintained their Ming-era ranks and were led by a mix of Banner and Green Standard officers.[24] These Chinese troops eventually outnumbered Banner troops three to one (about 600,000 Green Standard troops to 200,000 bannermen).

Even though the Manchu banners were the most effective fighting force during the Qing conquest of the Ming, most of the fighting was done by Chinese banners and Green Standard troops, especially in southern China where Manchu cavalry could play less of a role.[25] The banners also performed badly during the revolt of the Three Feudatories that erupted in southern China in 1673.[26] It was regular Chinese troops, albeit led by Manchu and Chinese officers, who helped the Qing to defeat their enemies in 1681 and thus consolidate their control over all of China.[26] Green Standard troops also formed the main personnel of the naval forces that defeated the Southern Ming dynasty resistance in Taiwan.[27]

The Banners and Green Standard troops were standing armies, paid for by the central government. In addition, regional governors from provincial down to village level maintained their own irregular local militias for police duties and disaster relief. These militias were usually granted small annual stipends from regional coffers for part-time service obligations.

The Qing divided the command structure of the Green Standard Army in the provinces between the high-ranking officers and low ranking officers, the best and strongest unit was under the control of the highest-ranking officers but at the same time, these units were outnumbered by other units divided between individual lower ranking officers so none of them could revolt on their own against the Qing because they did not control the entire armies.[28]

Manchu Generals and Bannermen were initially put to shame by the better performance of the Han Chinese Green Standard Army, who fought better than them against the rebels and this was noted by the Kangxi Emperor, leading him to task Generals Sun Sike, Wang Jinbao, and Zhao Liangdong to lead Green Standard Soldiers to crush the rebels.[29] The Qing thought that Han Chinese were superior at battling other Han people and so used the Green Standard Army as the dominant and majority army in crushing the rebels instead of Bannermen.[30] In northwestern China against Wang Fuchen, the Qing put Bannermen in the rear as reserves while they used Han Chinese Green Standard Army soldiers and Han Chinese Generals like Zhang Liangdong, Wang Jinbao, and Zhang Yong as the primary military forces, considering Han troops as better at fighting other Han people, and these Han generals achieved victory over the rebels.[31] Sichuan and southern Shaanxi were retaken by the Han Chinese Green Standard Army under Wang Jinbao and Zhao Liangdong in 1680, with Manchus only participating in dealing with logistics and provisions.[32] 400,000 Green Standard Army soldiers and 150,000 Bannermen served on the Qing side during the war.[32] 213 Han Chinese Banner companies, and 527 companies of Mongol and Manchu Banners were mobilized by the Qing during the revolt.[33] The Qing had the support of the majority of Han Chinese soldiers and Han elite against the Three Feudatories, since they refused to join Wu Sangui in the revolt, while the Eight Banners and Manchu officers fared poorly against Wu Sangui, so the Qing responded with using a massive army of more than 900,000 Han Chinese (non-Banner) instead of the Eight Banners, to fight and crush the Three Feudatories.[34] Wu Sangui's forces were crushed by the Green Standard Army, made out of defected Ming soldiers.[35]

The frontier in the south-west was extended slowly, in 1701 the Qing defeated Tibetans at the Battle of Dartsedo. The Dzungar Khanate conquered the Uyghurs in the Dzungar conquest of Altishahr and seized control of Tibet. Han Chinese Green Standard Army soldiers and Manchu bannermen were commanded by the Han Chinese General Yue Zhongqi in the Chinese expedition to Tibet (1720) which expelled the Dzungars from Tibet and placed it under Qing rule. At multiple places such as Lhasa, Batang, Dartsendo, Lhari, Chamdo, and Litang, Green Standard troops were garrisoned throughout the Dzungar war.[36] Green Standard Army troops and Manchu Bannermen were both part of the Qing force who fought in Tibet in the war against the Dzungars.[37] It was said that the Sichuan commander Yue Zhongqi (a descendant of Yue Fei) entered Lhasa first when the 2,000 Green Standard soldiers and 1,000 Manchu soldiers of the "Sichuan route" seized Lhasa.[38] According to Mark C. Elliott, after 1728 the Qing used Green Standard Army troops to man the garrison in Lhasa rather than Bannermen.[39] According to Evelyn S. Rawski both Green Standard Army and Bannermen made up the Qing garrison in Tibet.[40] According to Sabine Dabringhaus, Green Standard Chinese soldiers numbering more than 1,300 were stationed by the Qing in Tibet to support the 3,000 strong Tibetan army.[41]

Garrisons in peacetime

Banner Armies were broadly divided along ethnic lines, namely Manchu and Mongol. Although it must be pointed out that the ethnic composition of Manchu Banners was far from homogeneous as they included non-Manchu bondservants registered under the household of their Manchu masters. As the war with Ming dynasty progressed and the Han Chinese population under Manchu rule increased, Hong Taiji created a separate branch of Han Banners to draw on this new source of manpower. The Six Ministries and other major positions were filled with Han Bannermen chosen by the Qing.[42] It was Han Chinese Bannermen who were responsible for the successful Qing takeover of China. They made up the majority of governors in the early Qing and were the ones who governed and administered China after the conquest, stabilizing Qing rule.[43] Han Bannermen dominated governor-general posts in the time of the Shunzhi and Kangxi Emperors, as well as governor posts, largely excluding ordinary Han civilians.[44] The political barrier was between the commoners made out of non-bannermen and the "conquest elite", made out of Bannermen whether Han Chinese, Mongols or Manchu. It was not ethnicity which was the factor.[45]

The socio-military origins of the Banner system meant that population within each branch and their sub-divisions were hereditary and rigid. Only under special circumstances sanctioned by imperial edict were social movements between banners permitted. In contrast, the Green Standard Army was originally intended to be a professional force.

After defeating the remnants of the Ming forces, the Manchu Banner Army of approximately 200,000 strong at the time was evenly divided; half was designated the Forbidden Eight Banner Army (Chinese: 禁旅八旗; pinyin: jìnlǚ bāqí) and was stationed in Beijing. It served both as the capital's garrison and the Qing government's main strike force. The remainder of the Banner troops was distributed to guard key cities in China. These were known as the Territorial Eight Banner Army (simplified Chinese: 驻防八旗; traditional Chinese: 駐防八旗; pinyin: zhùfáng bāqí). The Manchu court, keenly aware its own minority status, reinforced a strict policy of racial segregation between the Manchus and Mongols from Han Chinese for fear of being sinicized by the latter. This policy applied directly to the Banner garrisons, most of which occupied a separate walled zone within the cities they were stationed in. In cities where there were limitation of space such as in Qingzhou, a new fortified town would be purposely erected to house the Banner garrison and their families. Beijing being the imperial seat, the regent Dorgon had the entire Chinese population forcibly relocated to the southern suburbs which became known as the "Outer Citadel" (Chinese: 外城; pinyin: wàichéng). The northern walled city called "Inner Citadel" (Chinese: 內城; pinyin: nèichéng) was portioned out to the remaining Manchu Eight Banners, each responsible for guarding a section of the Inner Citadel surrounding the Forbidden City palace complex.[lower-alpha 1]

Military training was undertaken by martial artists in the Qing armed forces.[46]

Associations for martial arts were joined by Manchu Bannermen in Beijing.[47]

A hall for martial arts was where the military careers of Muslim Generals Ma Fulu and Ma Fuxiang started in Hezhou.[48][49]

Soldiers and officers in the Qing army were taught by the Muslim martial arts instructor Wang Zi-Ping before he fought in the Boxer rebellion.[50] Another teacher of martial arts in the military in Beijing was Wang Xiang Zhai.[51] The trainers in martial arts in the army had to deal with a massive assortment of different armaments such as spears and swords.[52] Gunpowder weaponry had been long used by China so the mentality that melee combat in China being replaced out of thin air by western guns was a myth.[53] Cavalry were also taught martial arts. Martial arts were part of the exams for military officers.[54] Martial artists were among those who settled in urban from the countryside.[55] The Qing and Ming military drew on the Shaolin tradition.[56] Techniques and armaments cross fertilized across the army and civilian realms.[57] The army included trainers in martial arts from the Taoists.[58] The Taiping military had martial artists.[59]

Navy

The "sea ban" policy during the early Qing dynasty meant that the development of naval power stagnated. River and coastal naval defence was the responsibility of the waterborne units of the Green Standard Army, which were based at Jingkou (now Zhenjiang) and Hangzhou.

In 1661, a naval unit was established at Jilin to defend against Russian incursions into Manchuria. Naval units were also added to various Banner garrisons subsequently, referred to collectively as the "Eight Banners Navy". In 1677, the Qing court re-established the Fujian Fleet in order to combat the Ming-loyalist Kingdom of Tungning based on Taiwan. This conflict culminated in the Qing victory the Battle of Penghu in 1683 and the surrender of the Tungning shortly after the battle.

The Qing, like the Ming, placed considerable importance on the building of a strong navy. However unlike the Europeans, they did not perceive the need to dominate the open ocean and hence monopolise trade, and instead focused on defending, by means of patrols, their inner sea space. The Qing demarcated and controlled their inner seas in the same manner as land territory.[60]

The Kangxi Emperor and his successors established a four-zone sea defence system consisting of the Bohai Gulf (Dengzhou fleet, Jiaozhou fleet, Lüshun fleet and Tianjin/Daigu fleet), Jiangsu-Zhejiang coast (Jiangnan fleet and Zhejiang fleet), Taiwan Strait (Fujian fleet) and the Guangdong coast (Guangdong Governor's fleet and Guangdong regular fleet). The fleets were supported by a chain of coastal artillery batteries along the coast and "water castles" or naval bases. Qing warships of the Kangxi era had a crew of 40 seamen and were armed with cannons and wall guns of Dutch design.[61]

Although the Qing had invested in naval defences for their adjacent seas in earlier periods, after the death of the Qianlong Emperor in 1799, the navy decayed as more attention was directed to suppressing the Miao Rebellion and White Lotus Rebellion, which left the Qing treasury bankrupt. The remaining naval forces were badly overstretched, undermanned, underfunded and uncoordinated.[62]

Eighteenth century

The policy of posting Banner troops as territorial garrison was not to protect but to inspire awe in the subjugated populace at the expense of their expertise as cavalry. As a result, after a century of peace and lack of field training the Manchu Banner troops had deteriorated greatly in their combat worthiness. Secondly, before the conquest, the Manchu banner was a "citizen" army, and its members were Manchu farmers and herders obligated to provide military service to the state at times of war. The Qing government's decision to turn the banner troops into a professional force whose every welfare and need was met by state coffers brought wealth, and with it corruption, to the rank and file of the Manchu Banners and hastened its decline as a fighting force. Bannermen frequently went into debt as a result of drinking, gambling, and spending time at theaters and brothels, leading to a general ban on theater-going within the Eight Banners.[63]

At the same time, a similar decline was occurring in the Green Standard Army. During peacetime, soldiering became merely a source of supplementary income. Soldiers and commanders alike neglected training in pursuit of their own economic gains. Corruption was rampant as regional unit commanders submitted pay and supply requisitions based on exaggerated head counts to the quartermaster department and pocketed the difference. When Green Standard troops proved unable to fire their guns accurately while suppressing a rebellion of White Lotus followers under Wang Lun in 1774, the governor-general blamed the failure on enemy magic, prompting a furious reply from the Qianlong Emperor in which he described incompetence with firearms as a "common and pervasive disease" of the Green Standard Army, whose gunners were full of excuses.[64]

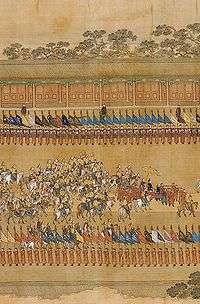

Qing emperors attempted to reverse the decline of the military through a variety of means. Although it was under the Qianlong Emperor that the empire expanded to its greatest extent, the emperor and his officers frequently made note of the decline of martial discipline among the troops.[65][66] Qianlong reinstituted the annual hunt at Mulan as a form of military training. Thousands of troops participated in these massive exercises, selected from among Eight Banners troops of both the capital and the garrisons.[67] Qianlong also promoted military culture, directing his court painters to produce a large number of works on military themes, including victories in battle, the grand inspections of the army, and the imperial hunt at Mulan.[68]

Technology

Qing armies in the eighteenth century may not have been as well-armed as their European counterparts, but under pressure from the imperial throne they proved capable of innovation and efficiency, sometimes in difficult circumstances. The Qing were consistently very keen on adopting Western military technology. In the Second Jinchuan War, for instance, the Qianlong emperor despatched the Jesuit Felix da Rocha, the director of the Bureau of Astronomy, to the front to cast heavy field cannon that could not be transported to the deep mountains in which the Jinchuan tribes lived.[69] The Qing army produced new cannons based on the designs supplied by the Jesuit Missionaries Ferdinand Verbiest in 1670s and Felix da Rocha in the 1770s. These cannon designs continued being reproduced in China until the First Opium War.[70]

Shi Lang's fleet to crush the Ming resistance in Taiwan incorporated Dutch naval technology.[71]

It is estimated that 30 to 40% of Chinese soldiers at the time of the First Opium War were equipped with firearms, typically matchlock muskets.[72]

When the Taiping Rebellion broke out in the 1850s, the Qing court found out belatedly that the Banner and Green Standards troops could neither put down internal rebellions nor keep foreign invaders at bay.

Transition and modernization

Early during the Taiping Rebellion, Qing forces suffered a series of disastrous defeats culminating in the loss of the regional capital city of Nanjing in 1853. The rebels massacred the entire Manchu garrison and their families in the city and made it their capital.[73] Shortly thereafter, a Taiping expeditionary force penetrated as far north as the suburbs of Tianjin in what was considered the imperial heartlands. In desperation the Qing court ordered a Chinese mandarin, Zeng Guofan, to organize regional (simplified Chinese: 团勇; traditional Chinese: 團勇; pinyin: tuányǒng) and village (simplified Chinese: 乡勇; traditional Chinese: 鄉勇; pinyin: xiāngyǒng) militias into a standing army called tuanlian to contain the rebellion. Zeng Guofan's strategy was to rely on local gentries to raise a new type of military organization from those provinces that the Taiping rebels directly threatened. This new force became known as the Xiang Army, named after the Hunan region where it was raised. The Xiang Army was a hybrid of local militia and a standing army. It was given professional training, but was paid for out of regional coffers and funds its commanders — mostly members of the Chinese gentry — could muster. The Xiang Army and its successor, the Huai Army, created by Zeng Guofan's colleague and student Li Hongzhang, were collectively called the "Yong Ying" (Brave Camp).[74]

Before forming and commanding the Xiang Army, Zeng Guofan had no military experience. Being a classically educated Mandarin, his blueprint for the Xiang Army was taken from a historical source — the Ming general Qi Jiguang, who, because of the weakness of regular Ming troops, had decided to form his own "private" army to repel raiding Japanese pirates in the mid-16th century. Qi Jiguang's doctrine was based on Neo-Confucian ideas of binding troops' loyalty to their immediate superiors and also to the regions in which they were raised. This initially gave the troops an excellent esprit de corps. Qi Jiguang's army was an ad hoc solution to the specific problem of combating pirates, as was Zeng Guofan's original intention for the Xiang Army, which was raise to eradicate the Taiping rebels. However, circumstances led to the Yongying system becoming a permanent institution within the Qing military, which in the long run created problems of its own for the beleaguered central government.

First, the Yongying system signaled the end of Manchu dominance in Qing military establishment. Although the Banners and Green Standard armies lingered on as parasites depleting resources, henceforth the Yongying corps became the Qing government's de facto first-line troops. Secondly the Yongying corps were financed through provincial coffers and were led by regional commanders. This devolution of power weakened the central government's grip on the whole country, a weakness further aggravated by foreign powers vying to carve up autonomous colonial territories in different parts of the Qing Empire in the later half of the 19th century. Despite these serious negative effects, the measure was deemed necessary as tax revenue from provinces occupied and threatened by rebels had ceased to reach the cash-strapped central government. Finally, the nature of Yongying command structure fostered nepotism and cronyism amongst its commanders, whom, as they ascended the bureaucratic ranks laid the seeds to Qing's eventual demise and the outbreak of regional warlordism in China during the first half of the 20th century.[74]

By the late 19th century, China was fast descending into a semi-colonial state. Even the most conservative elements within the Qing court could no longer ignore China's military weakness in contrast to the foreign "barbarians" literally beating down its gates. In 1860, during the Second Opium War, the capital Beijing was captured and the Summer Palace sacked by a relatively small Anglo-French coalition force numbering 25,000.

Self-Strengthening and military modernization

Although the Chinese invented gunpowder, and firearms had been in continual use in Chinese warfare since as far back as the Song dynasty, the advent of modern weaponry resulting from the European Industrial Revolution had rendered China's traditionally trained and equipped army and navy obsolete.

After the humiliating capture of Beijing and the sack of the Summer Palace in 1860, officials like Zeng Guofan, Li Hongzhang, and the Manchu Wenxiang made efforts to acquire advanced western weapons and copy western military organization.[75] Special brigades of Chinese soldiers equipped with modern rifles and commanded by foreign officers (one example is the Ever Victorious Army commanded by Frederick Townsend Ward and later Charles George Gordon) helped Zeng and Li to defeat the Taiping rebels.[75] Li Hongzhang's Huai Army also acquired western rifles and incorporated some western drills.[75] Meanwhile, in Beijing, Prince Gong and Wenxiang created an elite army, the "Peking Field Force", which was armed with Russian rifles and French cannon and drilled by British officers.[76] When this force of 2,500 bannermen defeated a bandit army more than ten times more numerous, they seemed to prove Wenxiang's point that a small but well-trained and well-equipped banner army would be sufficient to defend the capital in the future.[77]

One major emphasis of the reforms was to improve the weaponry of Chinese armies. In order to produce modern rifles, artillery, and ammunition, Zeng Guofan created an arsenal in Suzhou, which was moved to Shanghai and expanded into the Jiangnan Arsenal.[78] In 1866 the sophisticated Fuzhou Shipyard was created under the leadership of Zuo Zongtang, its focus being the building of modern warships for coastal defense.[78] From 1867 to 1874 it built fifteen new ships.[79] Other arsenals were created in Nanjing, Tianjin (it served as a major source of ammunition for northern Chinese armies in the 1870s and 1880s), Lanzhou (to support Zuo Zongtang's quelling of a large Muslim uprising in the northwest), Sichuan, and Shandong.[78] Prosper Giquel, a French naval officer who served as adviser at the Fuzhou Shipyard, wrote in 1872 that China was quickly becoming a formidable rival to western powers.[80]

Thanks to these reforms and improvements, the Qing government gained a major advantage over domestic rebels.[81] After vanquishing the Taiping in 1864, the newly equipped armies defeated the Nian Rebellion in 1868, the Guizhou Miao in 1873, the Panthay Rebellion in Yunnan in 1873, and in 1877 the massive Muslim uprising that had engulfed Xinjiang since 1862.[81] In addition to quelling domestic revolts, the Qing also fought foreign powers with relative success. Qing armies managed to solve the 1874 crisis with Japan over Taiwan diplomatically, forced the Russians out of the Ili River valley in 1881, and fought the French to a standstill in the Sino-French War of 1884–1885 despite many failures in naval warfare.[82]

Foreign observers reported that, when their training was complete, the troops stationed in the Wuchang garrison were the equal of contemporary European forces.[83] Mass media in the west during this era portrayed China as a rising military power due to its modernization programs and as a major threat to the western world, invoking fears that China would successfully conquer western colonies like Australia. Chinese armies were praised by John Russell Young, US envoy, who commented that "nothing seemed more perfect" in military capabilities, predicting a future confrontation between America and China."[84] The Russian military observer D. V. Putiatia visited China in 1888 and found that in Northeastern China (Manchuria) along the Chinese-Russian border, the Chinese soldiers were potentially able to become adept at "European tactics" under certain circumstances, and the Chinese soldiers were armed with modern weapons like Krupp artillery, Winchester carbines, and Mauser rifles.[85] On the eve of the First Sino-Japanese War, the German General Staff predicted a Japanese defeat and William Lang, who was a British advisor to the Chinese military, praised Chinese training, ships, guns, and fortifications, stating that "in the end, there is no doubt that Japan must be utterly crushed".[86]

The military improvements that resulted from modernizing reforms were substantial, but they still proved insufficient, as the Qing was soundly defeated by Meiji Japan in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895.[87] Even China's best troops the Huai Army and the Beiyang Fleet, both commanded by Li Hongzhang were no match for Japan's better-trained, better led, and faster army and navy.[88]

When it was first developed by Empress Dowager Cixi, the Beiyang Fleet was said to be the strongest navy in East Asia. Before her adopted son, Emperor Guangxu, took over the throne in 1889, Cixi wrote out explicit orders that the navy should continue to develop and expand gradually.[89] However, after Cixi went into retirement, all naval and military development came to a drastic halt. Japan's victories over China has often been falsely rumored to be the fault of Cixi.[90] Many believed that Cixi was the cause of the navy's defeat by embezzling funds from the navy in order to build the Summer Palace in Beijing. However, extensive research by Chinese historians revealed that Cixi was not the cause of the Chinese navy's decline. In actuality, China's defeat was caused by Emperor Guangxu's lack of interest in developing and maintaining the military.[89] His close adviser, Grand Tutor Weng Tonghe, advised Guangxu to cut all funding to the navy and army, because he did not see Japan as a true threat, and there were several natural disasters during the early 1890s which the emperor thought to be more pressing to expend funds on.[89]

The military defeats suffered by China has been attributed to the factionalism of regional military governors. For instance, the Beiyang Fleet refused to participate in the Sino-French War in 1884,[91] the Nanyang Fleet retaliating by refusing to deploy during the Sino-Japanese War of 1895.[92] Li Hongzhang wanted to personally maintain control of this fleet, many top vessels among its number, by keeping it in northern China and not let it slip into the control of southern factions.[93] China did not have a single admiralty in charge of all the Chinese navies before 1885;[94] the northern and southern Chinese navies did not cooperate, therefore enemy navies needed only to fight a segment of China's navy.[95]

New Armies

Losing the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 was a watershed for the Qing government. Japan, a country long regarded by the Chinese as little more than an upstart nation of pirates, had convincingly beaten its larger neighbour and in the process annihilated the Qing government's pride and joy — its modernized Beiyang Fleet, then deemed to be the strongest naval force in Asia. In doing so, Japan became the first Asian country to join the previously exclusively western ranks of colonial powers. The defeat was a rude awakening to the Qing court especially when set in the context that it occurred a mere three decades after the Meiji Restoration set a feudal Japan on course to emulate the Western nations in their economic and technological achievements. Finally, in December 1894, the Qing government took concrete steps to reform military institutions and to re-train selected units in westernized drills, tactics and weaponry. These units were collectively called the New Army. The most successful of these was the Beiyang Army under the overall supervision and control of a former Huai Army commander, General Yuan Shikai, who used his position to eventually become President of the Republic of China and finally emperor of China.[96]

During the Boxer Rebellion, Imperial Chinese forces deployed a weapon called "electric mines" on June 15, at the river Peiho river before the Battle of Dagu Forts (1900), to prevent the western Eight-Nation Alliance from sending ships to attack. This was reported by American military intelligence in the United States. War Dept. by the United States. Adjutant-General's Office. Military Information Division.[97][98] Different Chinese armies were modernized to different degrees by the Qing dynasty. For example, during the Boxer Rebellion, in contrast to the Manchu and other Chinese soldiers who used arrows and bows, the Muslim Kansu Braves cavalry had the newest carbine rifles.[99] The Muslim Kansu Braves used the weaponry to inflict numerous defeats upon western armies in the Boxer Rebellion, in the Battle of Langfang, and, numerous other engagements around Tianjin.[100] [101] The Times noted that "10,000 European troops where held in check by 15,000 Chinese braves". Chinese artillery fire caused a steady stream of casualties upon the western soldiers. During one engagement, heavy casualties were inflicted on the French and Japanese, and the British and Russians lost some men.[102] Chinese artillerymen during the battle also learned how to use their German bought Krupp artillery accurately, outperforming European gunners. The Chinese artillery shells slammed right on target into the western armies military areas.[103]

The military leaders and the armies formed in the late 19th century continued to dominate politics well into the 20th century. During what was called the Warlord Era (1916–1928) the late-Qing armies became rivals and fought among themselves and with new militarists.[104]

See also

- Baturu

- Chu Army

- Fujian Fleet

- Gansu Braves

- Gapsin Coup

- Great Hsi-Ku Arsenal

- Guangdong Fleet

- Hushenying

- Imo Incident

- Imperial Guards Brigade

- Jiangnan Daying

- Nanyang Fleet

- Nine Gates Infantry Commander

- Second rout of the Jiangnan Daying

- Shuishiying

- Wuwei Corps

References

- Elliott 2001, p. 40.

- Millward 2007, p. 95.

- Elliott 2001, pp. 40 (uniquely Manchu) and 57 (role on Nurhaci's success).

- Elliott 2001, p. 58.

- Elliott 2001, p. 59.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 34.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 58.

- Elliott 2001, p. 75.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 57.

- Roth Li 2002, pp. 57–58.

- Roth Li 2002, p. 58 ("Han-chün [Hanjun] banners"); Elliott 2001, p. 74 ("Chinese Eight Banners"); Crossley 1997, p. 204 ("Chinese-martial banners").

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0804746842.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. p. 128. ISBN 0520928849.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 103–5. ISBN 0520928849.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 324. ISBN 0804746842.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 331. ISBN 0804746842.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 325. ISBN 0804746842.

- Walthall, Anne, ed. (2008). Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0520254442.

- [Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China p. 135.

- [Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China p. 198.

- [Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China p. 206.

- Elliott 2001, p. 480 (integration of surrendered Ming troops into Green Standards); Crossley 1999, pp. 118–19 (Chinese troops integrated into the Chinese banners in 1644; access restricted starting in 1645).

- Wakeman 1985, p. 480, note 165.

- Elliott 2001, p. 128.

- Lococo Jr. 2002, p. 118.

- Lococo Jr. 2002, p. 120.

- Dreyer 2002, p. 35.

- Chu, Wen Djang (2011). The Moslem rebellion in northwest China, 1862 - 1878: a study of government minority policy (reprint ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-3111414508.

- Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo (24 January 2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1-135-78955-8.

- Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo (24 January 2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-135-78955-8.

- Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo (24 January 2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-1-135-78955-8.

- Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo (24 January 2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-135-78955-8.

- Henry Luce Foundation Professor of East Asian Studies Nicola Di Cosmo; Nicola Di Cosmo (24 January 2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. Routledge. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-135-78955-8.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- Xiuyu Wang (28 November 2011). China's Last Imperial Frontier: Late Qing Expansion in Sichuan's Tibetan Borderlands. Lexington Books. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-7391-6810-3.

- Yingcong Dai (2009). The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing. University of Washington Press. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-295-98952-5.

- Yingcong Dai (2009). The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing. University of Washington Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-295-98952-5.

- Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press. pp. 412–. ISBN 978-0-8047-4684-7.

- Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0.

green standard army lhasa.

- The Dynastic Centre and the Provinces: Agents and Interactions. BRILL. 17 April 2014. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-90-04-27209-5.

- Yoshiki Enatsu (2004). Banner Legacy: The Rise of the Fengtian Local Elite at the End of the Qing. Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-89264-165-9.

- Spencer 1990, p. 41.

- Spence 1988, pp. 4–5.

- James A. Millward; Ruth W. Dunnell; Mark C. Elliott; Philippe Forêt, eds. (31 July 2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-1-134-36222-6.

- Ba Gua Zhang An Historical Analysis. Ben Hill Bey. 2010. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-0-557-46679-5.

- Pamela Kyle Crossley (1990). Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World. Princeton University Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 0-691-00877-9.

- Jonathan Neaman Lipman (1 July 1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-0-295-80055-4.

- http://www.360doc.com/content/12/0715/19/8500692_224390692.shtml

- http://m.zwbk.org/lemma/457905 http://www.china.com.cn/guoqing/2016-01/27/content_37676554_6.htm http://culture.163.com/06/0222/13/2AIPRMAB00281MU3.html http://m.qulishi.com/news/201507/34764_5.html "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2016-05-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- C S Tang (21 March 2015). The Complete Book of Yiquan. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-85701-172-5.

- Thomas A. Green; Joseph R. Svinth (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-1-59884-243-2.

- Peter Allan Lorge (2012). Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4.

- Brian Kennedy; Elizabeth Guo (1 December 2007). Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Blue Snake Books. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-58394-194-2.

- Andrew D. Morris (2004). Marrow of the Nation: A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China. University of California Press. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-0-520-24084-1.

- Meir Shahar (2008). The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-8248-3110-3.

- Xiaobing Li (2012). China at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-1-59884-415-3.

- Vincent Goossaert; David A. Palmer (15 March 2011). The Religious Question in Modern China. University of Chicago Press. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-226-30418-2.

- Lily Xiao Hong Lee; Clara Lau; A.D. Stefanowska (17 July 2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: V. 1: The Qing Period, 1644-1911. Routledge. pp. 198–. ISBN 978-1-317-47588-0.

- Po, Chung-yam (28 June 2013). Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century (PDF) (Thesis). Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. pp. 85–95.

- Po, Chung-yam (28 June 2013). Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century (PDF) (Thesis). Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. pp. 116–151.

- Ronald C. Po (2018). The Blue Frontier: Maritime Vision and Power in the Qing Empire Cambridge Oceanic Histories. Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1108424615.

- Elliott 2001, pp. 284-290.

- Waley-Cohen 2006, pp. 63-65.

- Elliott 2001, pp. 283-284.

- Elliott 2001, pp. 299-300.

- Elliott 2001, pp. 184-186.

- Waley-Cohen 2006, pp. 84-87.

- Waley-Cohen 2006, p. 58.

- Waley-Cohen, Joanna (2000). The Sextants of Beijing: Global Currents in Chinese History. New York, London: W. W. Norton and Company. pp. 118–121. ISBN 039324251X.

- Po, Chung-yam (28 June 2013). Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century (PDF) (Thesis). Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. p. 113.

- Tonio Andrade (2017). The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History. Princeton University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0691178141.

- Crossley 1990, pp. 126–27.

- Liu & Smith 1980, pp. 202–10.

- Horowitz 2002, p. 156.

- Horowitz 2002, pp. 156–57.

- Crossley 1990, p. 145.

- Horowitz 2002, p. 157.

- Wright 1957, p. 212.

- Wright 1957, p. 220.

- Horowitz 2002, p. 158.

- Horowitz 2002, pp. 158–59.

- Bonavia, David (1995). China's Warlords. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 0-19-586179-5.

- David Scott (2008). China and the International System, 1840–1949: Power, Presence, and Perceptions in a Century of Humiliation. SUNY Press. pp. 111–12. ISBN 978-0-7914-7742-7.

- Alex Marshall (22 November 2006). The Russian General Staff and Asia, 1860-1917. Routledge. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-1-134-25379-1.

- Liu, Kwang-Ching (1978). John King Fairbank (ed.). The Cambridge History of China. Volume 11, Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911 Part 2 (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 0-521-22029-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horowitz 2002, p. 159.

- Elman 2005, pp. 379–83.

- Chang, Jung (2013). The Concubine Who Launched Modern China: Empress Dowager Cixi. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 182–84. ISBN 978-0307456700.

- Chang, Jung (2013). The Concubine Who Launched Modern China: Empress Dowager Cixi. New York: Anchor Books. pp. 160–61. ISBN 978-0307456700.

- Loir, M., L'escadre de l'amiral Courbet (Paris, 1886), 26–29, 37–65.

- Lung Chang [龍章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南與中法戰爭, Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993), 327–28.

- Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

Not surprisingly, considering Li Hongzhang's political power, many of the best and most modern ships found their way into Li's northern fleet, which never saw any action in the Sino-French conflict. In fact, fear that he might lost control over his fleet led Li to refuse to even consider sending his ships southward to aid the Fuzhou fleet against the French. Although Li later claimed that moving his fleet southward would have left northern China undefended, his decision has been criticized as a sign of China's factionalized government as well as its provincial north-south mindest.

- 姜文奎 (1987). 《中國歷代政制考》. 臺北市: 國立編譯館. pp. 839、840.

- Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 2012-01-18.

there was little, if any, coordination between the fleets in north and south China. The lack of a centralized admiralty commanding the entire navy meant that at any one time France opposed only a fraction of China's total fleet. This virtually assured French naval dominance in the upcoming conflict.

- Liu & Smith 1980, pp. 251–273.

- Monro MacCloskey (1969). Reilly's Battery: a story of the Boxer Rebellion. R. Rosen Press. p. 95. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- Stephan L'H. Slocum, Carl Reichmann, Adna Romanza Chaffee, United States. Adjutant-General's Office. Military Information Division (1901). Reports on military operations in South Africa and China. G.P.O. p. 533. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

June 15, it was learned that the mouth of the river was protected by electric mines, that the forts at Taku were.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Diana Preston (2000). The boxer rebellion: the dramatic story of China's war on foreigners that shook the world in the summer of 1900. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 145. ISBN 0-8027-1361-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Elliott (2002), p. 204.

- Wood, Frances. "The Boxer Rebellion, 1900: A Selection of Books, Prints and Photographs". The British Library. Archived from the original on 2011-10-29. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Arthur Henderson Smith (1901). China in convulsion, Volume 2. F. H. Revell Co. p. 448. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Arthur Henderson Smith (1901). China in convulsion, Volume 2. F. H. Revell Co. p. 446. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- For an overview, see Edward L. Dreyer. China at War, 1901–1949. (London; New York: Longman, Modern Wars in Perspective, 1995). ISBN 0582051258.

Works cited

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1990), Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691055831.

- —— (1997), The Manchus, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 1557865604 (hardback), ISBN 0631235914 (paperback).

- —— (1999), A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0520215664.

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2002), "Continuity and Change", in David A. Graff; Robin Higham (eds.), A Military History of China, Boulder, Colorado, and Oxford, England: Westview Press, pp. 19–38, ISBN 0813337364 (hardcover), ISBN 0813339901 (paperback).

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001), The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0804746842.

- Elman, Benjamin A. (2005), On Their Own Terms: Science in China, 1550–1900, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674016858.

- Horowitz, Richard S. (2002), "Beyond the Marble Boat: The Transformation of the Chinese Military, 1850–1911", in David A. Graff; Robin Higham (eds.), A Military History of China, Boulder, Colorado, and Oxford, England: Westview Press, pp. 153–74, ISBN 0813337364 (hardcover), ISBN 0813339901 (paperback).

- Liu, Kwang-ching; Smith, Richard J. (1980), "The Military Challenge: The North-west and the Coast", in John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett (eds.), Cambridge History of China, Volume 11, Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911, Part 2, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521220297.

- Lococo Jr., Paul (2002), "The Qing Empire", in David A. Graff; Robin Higham (eds.), A Military History of China, Boulder, Colorado, and Oxford, England: Westview Press, pp. 115–33, ISBN 0813337364 (hardcover), ISBN 0813339901 (paperback).

- Roth Li, Gertraude (2002), "State Building Before 1644", in Peterson, Willard J. (ed.), Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9, Part 1:The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–72, ISBN 0521243343.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1985), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China, Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, ISBN 0520048040. In two volumes.

- Waley-Cohen, Joanna (2006), The Culture of War in China: Empire and the Military under the Qing Dynasty, London: I.B. Tauris, International Library of War Studies, ISBN 1845111591.

- Wright, Mary C. (1957), The Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism: The T'ung-Chih Restoration, 1862–1874, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Further reading

- Elleman, Bruce A. (2001), Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989, London and New York: Routledge, Warfare and History, ISBN 0415214734.

- Graff, David A. and Robin D. S. Higham. A Military History of China. (Boulder, Colo. Oxford: Westview, 2002). ISBN 0813339901.

- Meyer-Fong, Tobie S (2013), What Remains: Coming to Terms with Civil War in 19th Century China, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 9780804754255.

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005), China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia, Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 067401684X.

- Platt, Stephen R. (2012), Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War, New York: Knopf, ISBN 9780307271730.

- Yu, Maochun (2002), "The Taiping Rebellion: A Military Assessment of Revolution and Counterrevolution", in David A. Graff; Robin Higham (eds.), A Military History of China, Boulder, Colorado, and Oxford, England: Westview Press, pp. 135–52, ISBN 0813337364 (hardcover), ISBN 0813339901 (paperback).