Xianbei

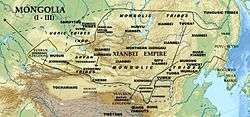

The Xianbei (/ʃjɛnˈbeɪ/; Chinese: 鮮卑; pinyin: Xiānbēi) were an ancient nomadic people that once resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes in what is today Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Northeastern China. They originated from the Donghu people who splintered into the Wuhuan and Xianbei when they were defeated by the Xiongnu at the end of the 3rd century BC. The Xianbei were largely subordinate to larger nomadic powers and the Han dynasty until they gained prominence in 87 AD by killing the Xiongnu chanyu Youliu. However unlike the Xiongnu, the Xianbei political structure lacked the organization to pose a concerted challenge to the Chinese for most of their time as a nomadic people.

| History of Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancient period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modern period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Xianbei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 鮮卑 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 鲜卑 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After suffering several defeats by the end of the Three Kingdoms period, the Xianbei migrated south and settled in close proximity to Chinese society and submitted as vassals, being granted the titles of Dukes. As the Xianbei Murong, Tuoba and Duan tribes were one of the Five Barbarians who were vassals of the Han Chinese Western Jin and Eastern Jin dynasties, they took part in the Uprising of the Five Barbarians as allies of the Han Chinese Eastern Jin against the other four barbarians, the Xiongnu, Jie, Di and Qiang.

The Xianbei were at one point all defeated and conquered by the Di Former Qin empire before it fell apart at the Battle of Fei River at the hands of the Eastern Jin. The Xianbei later founded their own states and reunited northern China as the Northern Wei. These states opposed and promoted sinicization at one point or another but trended towards the latter and had merged with the general Chinese population by the Tang dynasty.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Etymology

Paul Pelliot tentatively reconstructs the Later Han Chinese pronunciation of 鮮卑 as */serbi/, from *Särpi, after noting that Chinese scribes used 鮮 to transcribe Middle Persian sēr (lion) and 卑 to transcribe foreign syllable /pi/; for instance, Sanskrit गोपी gopī "milkmaid, cowherdess" became Middle Chinese 瞿卑 (ɡɨo-piᴇ) (> Mand. qúbēi).[7]

*Särpi may be linked, on the one hand, to Mongolic root *ser ~*sir which means "crest, bristle, sticking out, projecting, etc." (cf. Khalkha сэрвэн serven), possibly referring to the Xianbei's horses (semantically analogous with the Turkic ethnonym Yabaqu < Yapağu 'matted hair or wool', later 'a matted-haired animal, i.e. a colt')[8] Book of Later Han and Book of Wei stated that: before becoming an ethnonym, Xianbei had been a toponym, referring to the Great Xianbei mountains (大鮮卑山), which is now identified as the Greater Khingan range (simplified Chinese: 大兴安岭; traditional Chinese: 大興安嶺; pinyin: Dà Xīng'ān Lǐng).[9][10][11]

Shimunek (2018) reconstructs *serbi for Xiānbēi and *širwi for 室韋 Shìwéi < MC *ɕiɪt̚-ɦʉi.[12] This same root might be the origin of ethnonym Sibe.

History

Origin

When the Donghu "Eastern Barbarians" were defeated by Modu Chanyu around 208 BC, the Donghu splintered into the Xianbei and Wuhuan.[13] According to the Book of the Later Han, "the language and culture of the Xianbei are the same as the Wuhuan".[14]

The first significant contact the Xianbei had with the Han dynasty was in 41 and 45 when they joined the Wuhuan and Xiongnu in raiding Han territory.[15]

In 49, the governor Ji Tong convinced the Xianbei chieftain Pianhe to turn on the Xiongnu with rewards for each Xiongnu head they collected.[15] In 54, Yuchouben and Mantou of the Xianbei paid tribute to Emperor Guangwu of Han.[16]

In 58, the Xianbei chieftain Pianhe attacked and killed Xinzhiben, a Wuhuan leader causing trouble in Yuyang Commandery.[17]

In 85, the Xianbei secured an alliance with the Dingling and Southern Xiongnu.[15]

In 87, the Xianbei attacked the Xiongnu chanyu Youliu and killed him. They flayed him and his followers and took the skins back as trophies.[18]

Xianbei Conferedation

After the downfall of the Xiongnu, the Xianbei established their confederation in Mongolia starting from AD 93.

In 109, the Wuhuan and Xianbei attacked Wuyuan Commandery and defeated local Han forces.[19] The Southern Xiongnu chanyu Wanshishizhudi rebelled against the Han and attacked the Emissary Geng Chong but failed to oust him. Han forces under Geng Kui retaliated and defeated a force of 3,000 Xiongnu but could not take the Southern Xiongnu capital due to disease among the horses of their Xianbei allies.[19]

The Xianbei under Qizhijian raided Han territory four times from 121 to 138. .[20] In 145, the Xianbei raided Dai Commandery.[21]

Around 155, the northern Xiongnu were "crushed and subjugated" by the Xianbei. Their chief, known by the Chinese as Tanshihuai, then advanced upon and defeated the Wusun of the Ili region by 166. Under Tanshihuai, the Xianbei extended their territory from the Ussuri to the Caspian Sea. He divided the Xianbei empire into three sections, each ruled by twenty clans. Tanshihuai then formed an alliance with the southern Xiongnu to attack Shaanxi and Gansu. Han dynasty successfully repulsed their attacks in 158, 177. The Xianbei might have also attacked Wa (Japan) with some success.[22][23][24]

In 177 AD, Xia Yu, Tian Yan and the Tute Chanyu led a force of 30,000 against the Xianbei. They were defeated and returned with only a quarter of their original forces.[25] A memorial made that year records that the Xianbei had taken all the lands previously held by the Xiongnu and their warriors numbered 100,000. Han deserters who sought refuge in their lands served as their advisers and refined metals as well as wrought iron came into their possession. Their weapons were sharper and their horses faster than those of the Xiongnu. Another memorial submitted in 185 states that the Xianbei were making raids on Han settlements nearly every year.[26]

Three Kingdoms

The loose Xianbei confederacy lacked the organization of the Xiongnu but was highly aggressive until the death of their khan Tanshihuai in 182.[27] Tanshihuai's son Helian lacked his father's abilities and was killed in a raid on Beidi in 186.[28] Helian's brother Kuitou succeeded him, but when Helian's son Qianman came of age, he challenged his uncle to succession, destroying the last vestiges of unity among the Xianbei. By 190, the Xianbei had split into three groups with Kuitou ruling in Inner Mongolia, Kebineng in northern Shanxi, and Suli and Mijia in northern Liaodong. In 205, Kuitou's brothers Budugen and Fuluohan succeeded him. After Cao Cao defeated the Wuhuan at the Battle of White Wolf Mountain in 207, Budugen and Fuluohan paid tribute to him. In 218, Fuluohan met with the Wuhuan chieftain Nengchendi to form an alliance, but Nengchendi double crossed him and called in another Xianbei khan, Kebineng, who killed Fuluohan.[29] Budugen went to the court of Cao Wei in 224 to ask for assistance against Kebineng, but he eventually betrayed them and allied with Kebineng in 233. Kebineng killed Budugen soon afterwards.[30]

Kebineng was from a minor Xianbei tribe. He rose to power west of Dai Commandery by taking in a number of Chinese refugees, who helped him drill his soldiers and make weapons. After the defeat of the Wuhuan in 207, he also sent tribute to Cao Cao, and even provided assistance against the rebel Tian Yin. In 218 he allied himself to the Wuhuan rebel Nengchendi but they were heavily defeated and forced back across the frontier by Cao Zhang. In 220 he acknowledged Cao Pi as emperor of Cao Wei. Eventually he turned on the Wei for frustrating his advances on another Xianbei khan, Sui. Kebineng conducted raids on Cao Wei before he was killed in 235, after which his confederacy disintegrated.[31]

Many of the Xianbei tribes migrated south and settled on the borders of the Wei-Jin dynasties. In 258 Tuoba Liwei's people settled in Yanmen Commandery.[32] The Yuwen tribe settled between the Luan River and Liucheng. The Murong and Duan tribes became vassals of the Sima clan. An offshoot of the Murong tribe moved west into northern Qinghai and mixed with the native Qiang people, becoming Tuyuhun.[15]

In 279, the Xianbei made one last attack on Liang Province but they were defeated by Ma Long.[22]

Sixteen Kingdoms and the Northern Wei

The 3rd century saw both the fragmentation of the Xianbei in 235 and the branching out of the various Xianbei tribes.

The Xianbei tribes Tuoba, Murong and Duan submitted to the Western Jin dynasty as vassals, the Tuoba were made Dukes of Dai (Sixteen Kingdoms), the Murong were made Dukes of Liaodong, and the Duan were made Dukes of Liaoxi. The three Xianbei tribes fought on the Western Jin side against the other four barbarians in the Uprising of the Five Barbarians after a Xiongnu and Jie led slave revolt toppled Western Jin rule in northern China. Mass number of Chinese officers, soldiers and civilians fled south to join the Eastern Jin or north to join the Xianbei duchies which remained in direct communication with the Eastern Jin in southern China, receiving orders.

The Xianbei later establish six significant empires of their own such as the Former Yan (281-370), Western Yan (384-394), Later Yan (384-407), Southern Yan (398-410), Western Qin (385-430) and Southern Liang (397-414). The Xianbei were all conquered by the Di Former Qin empire in northern China before its defeat at the Battle of Fei River and subsequent collapse.

Most of them were unified by the Tuoba Xianbei, who established the Northern Wei (386-535), which was the first of the Northern Dynasties (386-581) founded by the Xianbei.[33][34][35]

Sinicization and assimilation

Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei established a policy of systematic sinicization that was continued by his successors. Xianbei traditions were largely abandoned. The royal family took the sinicization a step further by changing their family name to Yuan. Marriages to Chinese families were encouraged.

The Northern Wei started to arrange for Han Chinese elites to marry daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba royal family in the 480s.[36] More than fifty percent of Tuoba Xianbei princesses of the Northern Wei were married to southern Han Chinese men from the imperial families and aristocrats from southern China of the Southern dynasties who defected and moved north to join the Northern Wei.[37] Some Han Chinese exiled royalty fled from southern China and defected to the Xianbei. Several daughters of the Xianbei Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei were married to Han Chinese elites, the Liu Song royal Liu Hui (刘辉), married Princess Lanling (蘭陵公主) of the Northern Wei,[38][39][40][41][42] Princess Huayang (華陽公主) to Sima Fei (司馬朏), a descendant of Jin dynasty (265–420) royalty, Princess Jinan (濟南公主) to Lu Daoqian (盧道虔), Princess Nanyang (南阳长公主) to Xiao Baoyin (萧宝夤), a member of Southern Qi royalty.[43] Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei's sister the Shouyang Princess was wedded to The Liang dynasty ruler Emperor Wu of Liang's son Xiao Zong 蕭綜.[44]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi (司馬楚之) as a refugee. A Northern Wei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong (司馬金龍). Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.[45]

In 534, the Northern Wei split into an Eastern Wei (534–550) and a Western Wei (535–556) after an uprising in the steppes of North China inhabited by Xianbei and other nomadic peoples.[46] The former evolved into the Northern Qi (550-577), and the latter into the Northern Zhou (557-581), while the Southern Dynasties were pushed to the south of the Yangtze River. In 581, the Prime Minister of Northern Zhou, Yang Jian, founded the Sui dynasty (581-618). His son, the future Emperor Yang of Sui, absorbed the Chen Dynasty (557-589), the last kingdom of the Southern Dynasties, thereby unifying much of China. After the Sui came to an end amidst peasant rebellions and renegade troops, his cousin, Li Yuan, founded the Tang dynasty (618-907). Sui and Tang dynasties were founded by Han generals who also served the Northern Wei dynasty.[47][48] Through these political establishments, the Xianbei who entered China were largely merged with the Chinese, examples such as the wife of Emperor Gaozu of Tang, Duchess Dou and Emperor Taizong of Tang's wife, Empress Zhangsun, both have Xianbei ancestries,[49] while those who remained behind in the northern grassland emerged as later powers to rule over China as Mongol Yuan Dynasty and Manchu Qing Dynasty.

In the West, the Xianbei kingdom of Tuyuhun remained independent until defeated by the Tibetan Empire in 670. After the fall of the kingdom, the Xianbei people underwent a massive diasporisation over a vast territory that stretched from the northwest into central and eastern parts of China. Murong Nuohebo led the Tuyuhun people to migrated eastward into central China and settled in modern Yinchuan, Ningxia.

Art

Art of the Xianbei portrayed their nomadic lifestyle and consisted primarily of metalwork and figurines. The style and subjects of Xianbei art were influenced by a variety of influences, and ultimately, the Xianbei were known for emphasizing unique nomadic motifs in artistic advancements such as leaf headdresses, crouching and geometricized animals depictions, animal pendant necklaces, and metal openwork.[50]

Leaf headdresses

The leaf headdresses were very characteristic of Xianbei culture, and they are found especially in Murong Xianbei tombs. Their corresponding ornamental style also links the Xianbei to Bactria. These gold hat ornaments represented trees and antlers and, in Chinese, they are referred to as buyao ("step sway") since the thin metal leaves move when the wearer moves. Sun Guoping first uncovered this type of artifact, and defined three main styles: "Blossoming Tree" (huashu), which is mounted on the front of a cap near the forehead and has one or more branches with hanging leaves that are circle or droplet shaped, "Blossoming Top" (dinghua), which is worn on top of the head and resembles a tree or animal with many leaf pendants, and the rare "Blossoming Vine" (huaman), which consists of "gold strips interwoven with wires with leaves."[51] Leaf headdresses were made with hammered gold and decorated by punching out designs and hanging the leaf pendants with wire. The exact origin, use, and wear of these headdresses is still being investigated and determined. However, headdresses similar to those later also existed and were worn by women in the courts.[50][51]

Animal iconography

Another key form of Xianbei art is animal iconography, which was implemented primarily in metalwork. The Xianbei stylistically portrayed crouching animals in geometricized, abstracted, repeated forms, and distinguished their culture and art by depicting animal predation and same-animal combat. Typically, sheep, deer, and horses were illustrated. The artifacts, usually plaques or pendants, were made from metal, and the backgrounds were decorated with openwork or mountainous landscapes, which harks back to the Xianbei nomadic lifestyle. With repeated animal imagery, an openwork background, and a rectangular frame, the included image of the three deer plaque is a paradigm of the Xianbei art style. Concave plaque backings imply that plaques were made using lost-wax casting, or raised designs were impressed on the back of hammered metal sheets.[52][53]

Horses

The nomadic traditions of the Xianbei inspired them to portray horses in their artwork. The horse played a large role in the existence of the Xianbei as a nomadic people, and in one tomb, a horse skull lay atop Xianbei bells, buckles, ornaments, a saddle, and one gilded bronze stirrup.[54] The Xianbei not only created art for their horses, but they also made art to depict horses. Another recurring motif was the winged horse. It has been suggested by archaeologist Su Bai that this symbol was a "heavenly beast in the shape of a horse" because of its prominence in Xianbei mythology.[52] This symbol is thought to have guided an early Xianbei southern migration, and is a recurring image in many Xianbei art forms.

Figurines

Xianbei figurines help to portray the people of the society by representing pastimes, depicting specialized clothing, and implying various beliefs. Most figurines have been recovered from Xianbei tombs, so they are primarily military and musical figures meant to serve the deceased in afterlife processions and guard the tomb. Furthermore, the figurine clothing specifies the according social statuses: higher-ranking Xianbei wore long-sleeved robes with a straight neck shirt underneath, while lower-ranking Xianbei wore trousers and belted tunics.[55]

Buddhist influences

Xianbei Buddhist influences were derived from interactions with Han culture. The Han bureaucrats initially helped the Xianbei run their state, but eventually the Xianbei became Sinophiles and promoted Buddhism. The beginning of this conversion is evidenced by the Buddha imagery that emerges in Xianbei art. For instance, the included Buddha imprinted leaf headdress perfectly represents the Xianbei conversion and Buddhist synthesis since it combines both the traditional nomadic Xianbei leaf headdress with the new imagery of Buddha. This Xianbei religious conversion continued to develop in the Northern Wei dynasty, and ultimately led to the creation of the Yungang Grottoes.[50]

Language

It is widely theorized that the Xianbei spoke a language related to the Mongolic languages or Turkic languages. Claus Schönig writes:

The Xianbei derived from the context of the Donghu, who are likely to have contained the linguistic ancestors of the Mongols. Later branches and descendants of the Xianbei include the Tabghach and Khitan, who seem to have been linguistically Para-Mongolic. [...] Opinions differ widely as to what the linguistic impact of the Xianbei period was. Some scholars (like Clauson) have preferred to regard the Xianbei and Tabghach (Tuoba) as Turks, or even as Bulghar Turks, with the implication that the entire layer of early Turkic borrowings in Mongolic would have been received from the Xianbei, rather than from the Xiongnu. However, since the Mongolic (or Para-Mongolic) identity of the Xianbei is increasingly obvious in the light of recent progress in Khitan studies, it is more reasonable to assume (with Doerfer) that the flow of linguistic influence from Turkic (or Bulghar Turkic) into Mongolic was at least partly reversed during the Xianbei period, yielding the first identifiable layer of Mongolic (or Para-Mongolic) loanwords in Turkic. [56]

It is also possible that the Xianbei spoke more than one language.[57]

Anthropology

According to Sinologist Penglin Wang, some Xianbei had Caucasoid-featured traits such as blue eyes, blonde hair and white skin due to absorbing some Indo-European elements. The Xianbei were described as white on several occasions. The Book of Jin states that in the state of Cao Wei, Xianbei immigrants were known as the white tribe. The ruling Murong clan of Former Yan were referred to by their Former Qin adversaries as white slaves. According to Fan Wenlang et al. the Murong people were considered "white" by the Chinese due to the complexion of their skin color. In the Jin dynasty, Murong women were sold off to many bureaucrat and aristocrats and they were also given to their servants and concubines. The mother of Emperor Ming of Jin, Lady Xun, was a lowly concubine possibly of Xianbei stock. During a confrontation between Emperor Ming and a rebel force in 324, his enemies were confused by his appearance, and thought he was a Xianbei due to his yellow beard.[58] Emperor Ming's yelllowish hair could have been inherited from his mother, who was either Xianbei or Jie. During the Tang dynasty, the poet Zhang Ji described the Xianbei entering Luoyang as "yellow-headed". During the Song dynasty, the poet and painter Su Shi was inspired by a painting of a Xianbei riding a horse and wrote a poem describing an elderly Xianbei with reddish hair and blue eyes.[59]

There was undoubtedly some range of variation within their population. Yellow hair in Chinese sources could have meant brown rather than blonde and described other people such as the Jie rather than the Xianbei. Historian Edward H. Schafer believes many of the Xianbei were blondes, but others such as Charles Holcombe think it is "likely that the bulk of the Xianbei were not visibly very different in appearance from the general population of northeastern Asia."[57] Chinese anthropologist Zhu Hong and Zhang Quan-chao studied Xianbei crania from several sites of Inner Mongolia and noticed that anthropological features of studied Xianbei crania show that the racial type is closely related to the modern East-Asians, and some physical characteristics of those skulls are closer to modern Mongols, Manchu and Han Chinese.[60]

Genetics

A genetic study published in The FEBS Journal in October 2006 examined the mtDNA of sixteen Tuoba Xianbei buried at the Qilang Mountain Cemetery in Inner Mongolia, China. The fifteen samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups D (7 samples), C (5 samples), B (2 samples) and A.[61] These haplogroups are characteristic of Northeast Asians.[62] Among modern populations they were found to be most closely related to the Oroqen people.[63]

A genetic study published in the Russian Journal of Genetics in April 2014 examined the mtDNA of seventeen Tuoba Xianbei buried at the Shangdu Dongdajing cemetery in Inner Mongolia, China. The seventeen samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups D4 (four samples), D5 (three samples), C (five samples), A (three samples), G and B.[64]

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in November 2007 examined of 17 individuals buried at a Murong Xianbei cemetery in Lamadong, Liaoning, China ca. 300 AD.[65] They were determined to be carriers of the maternal haplogroups J1b1, D (three samples), F1a (three samples), M, B, B5b, C (three samples) and G2a.[66] These haplogroups are common among East Asians and some Siberians. The maternal haplogroups of the Murong Xianbei were noticeably different from those of the Huns and Tuoba Xianbei.[65]

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in August 2018 noted that the paternal haplogroup C2b1a1b has been detected among the Xianbei and the Rouran, and was probably an important lineage among the Donghu people.[67]

Notable people

Pre-dynastic

- Tanshihuai (檀石槐, 130–182), Xianbei leader who led the Xianbei State until his death in 182

- Kebineng (軻比能, died 235), a Xianbei chieftain who lived during the late Eastern Han dynasty and Three Kingdoms period

Sixteen Kingdoms

- Murong Huang (慕容皝, 297–348), founder of the state Former Yan

- Murong Jun (慕容儁, 319–360), was the second ruler of the state Former Yan

- Murong Chui (慕容垂, 326–396), was a general of the state Former Yan who later became the founding emperor of Later Yan

- Murong Ke (慕容恪, died 367), a famed general and statesman of the state Former Yan

- Murong De (慕容德, 336–405), founder of the state Southern Yan

- Murong Chao (慕容超, 385–410), was the last emperor of the Murong Xianbei state Southern Yan

Northern dynasties

- Tuoba Gui (拓跋珪, 371–409), founding emperor of the Northern Wei

- Tuoba Tao (拓拔燾, 408–452), was the third emperor of the Northern Wei

- Yuwen Tai (宇文泰, 507–556), a paramount general of the state Western Wei, a branch successor state of Northern Wei

- Dugu Xin (独孤信, 503–24 April 557), a paramount general of the state Western Wei

- Yuchi Jiong (尉遲迥, died 580), a paramount general of the states Western Wei and Northern Zhou

- Lou Zhaojun (婁昭君, 501–562), was an empress dowager of the state Northern Qi

- Lu Lingxuan (陸令萱, died 577), was a lady in waiting in the palace of the state Northern Qi

- Yuwen Hu (宇文護, 513–572), a regent of the state Northern Zhou

- Yuwen Yong (宇文邕, 543–578), emperor of the state Northern Zhou

Sui

- Dugu Qieluo (獨孤伽羅, 544–September 10, 602), formally Empress Wenxian (文獻皇后), was an empress of the Sui dynasty

- Yuchi Yichen (尉遲義臣, died 617), a prominent general of Sui Dynasty

- Yuwen Shu (宇文述, died 616), a paramount general of Sui Dynasty

Tang

- Empress Zhangsun (長孫皇后, 15 March 601 – 28 July 636), was an empress of Tang Dynasty. She was the wife of Emperor Taizong

- Zhangsun Wuji (長孫無忌, died 659), a paramount official who served both as general and chancellor in the early Tang dynasty

- Yuchi Jingde (尉遲敬德, 585–658), a famous general who lived in the early Tang dynasty, Yuchi Jingde and another general Qin Shubao are worshipped as door gods in Chinese folk religion

- Qutu Tong (屈突通, 557-628), a general in Sui and Tang dynasties of China. He was listed as one of 24 founding officials of Tang Dynasty honored on the Lingyan Pavilion due to his contributions in wars during the transitional period from Sui to Tang

- Yuwen Shiji (宇文士及, died 642), an official who served both as general and chancellor in the early Tang dynasty

- Yu Zhining (于志寧, 588–665), a chancellor of Tang dynasty, during the reigns of Emperor Taizong and Emperor Gaozong

Modern descendants

Most Xianbei clans adopted Chinese family names during Northern Wei Dynasty. In particular, many were sinicized under Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei.

The Northern Wei's Eight Noble Xianbei surnames 八大贵族 were the Buliugu 步六孤, Helai 賀賴, Dugu 獨孤, Helou 賀樓, Huniu 忽忸, Qiumu 丘穆, Gexi 紇奚, and Yuchi 尉遲.

The "Monguor" (Tu) people in modern China may have descended from the Xianbei who were led by Tuyuhun Khan to migrate westward and establish the Tuyuhun Kingdom (284-670) in the third century and Western Xia (1038–1227) through the thirteenth century.[68] Today they are primarily distributed in Qinghai and Gansu Province, and speak a Mongolic language.

The Xibe or "Xibo" people also believe they are descendants of the Xianbei, with considerable controversies that have attributed their origins to the Jurchens, the Elunchun, and the Xianbei.[69][70]

Xianbei descendants among the Korean population carry surnames such as Mo 모 Chinese: 慕; pinyin: mù; Wade–Giles: mu (shortened from Murong), Seok Sŏk Sek 석 Chinese: 石; pinyin: shí; Wade–Giles: shih (shortened from Wushilan 烏石蘭, Won Wŏn 원 Chinese: 元; pinyin: yuán; Wade–Giles: yüan (the adopted Chinese surname of the Tuoba), Dokgo 독고 Chinese: 獨孤; pinyin: Dúgū; Wade–Giles: Tuku (from Dugu).[71][72][73][74][75][76][77]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Xianbei. |

- Wen Yang (Three Kingdoms)

- War of the Eight Princes

- Change of Xianbei names to Han names

- War between Ran Min and Murong Xianbei

- Battle of Canhe Slope

- Northern Wei Dynasty

- Sixteen Kingdoms

- Northern Qi

- Gao Huan

- Lou Zhaojun

- Han Zhangluan

- Northern Zhou

- Yuwen Tai

- Tribes in Chinese history

- Wu Hu

References

- "The Sixteen States of the Five Barbarian Peoples 五胡十六國". www.chinaknowledge.de.

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 186–87.

- Tanigawa, Michio; Fogel, Joshua (1985). Medieval Chinese Society and the Local "community". University of California Press. pp. 120–21.

- Van Der Veer, Peter (2002). "Contexts of Cosmopolitanism". In Vertovec, Steven; Cohen, Robin (eds.). Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context and Practice. Oxford University Press. pp. 200–01.

- Dardess, John W. (2010). Governing China: 150–1850. Hackett. p. 9.

- "The Xianbei: A Chinese Dynasty Emerges from Nomadic Warriors of the Steppe | Ancient Origins".

- Toh, Hoong Teik (2005). "The -yu Ending in Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Gaoju Onomastica. Appendix I: the ethnicon Xianbei" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 146: 10–12.

- Golden, Peter B. “The Stateless Nomads of Central Eurasia”, in Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity Edited by DiCosmo, Maas. p. 347-348. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316146040.024

- Hou Hanshu vol. 90 "鮮卑者,亦東胡之支也,別依鮮卑山,故因號焉" "the Xianbei people branched off from the so-called 'Eastern Hu' and came to settle around Mt. Xianbei after which name they were designated" translated by Toh (2005)

- Weishu vol. 1

- Tseng, Chin Yin (2012). The Making of the Tuoba Northern Wei: Constructing Material Cultural Expressions in the Northern Wei Pingcheng Period (398-494 CE) (PhD). University of Oxford. p. 1.

- Shimunek, Andrew. "Early Serbi-Mongolic-Tungusic lexical contact: Jurchen numerals from the 室韦 Shirwi (Shih-wei) in North China". Academia.edu. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. p. 164

- Chen, Sanping (1996). "A-Gan Revisited — The Tuoba's Cultural and Political Heritage". Journal of Asian History. 30 (1): 46–78. JSTOR 41931010.

- http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Altera/xianbei.html

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 1016.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 899.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 991.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 782.

- de Crespigny 2017.

- Cosmo 2009, p. 106.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- "Nomads in Central Asia." N. Ishjamts. In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 155-156.

- SGZ 30. 837–838, note. 1.

- Cosmo 2009, p. 107.

- Twitchett 2008, p. 445.

- de Crespigny 2017, p. 401.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 320.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 237.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 25.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 289.

- de Crespigny 2017, p. 502.

- Ma, Changshou [馬長壽] (1962). Wuhuan yu Xianbei [Wuhuan and Xianbei] 烏桓與鮮卑. Shanghai [上海], Shanghai ren min chu ban she [Shanghai People's Press] 上海人民出版社.

- Liu, Xueyao [劉學銚] (1994). Xianbei shi lun [the Xianbei History] 鮮卑史論. Taibei [台北], Nan tian shu ju [Nantian Press] 南天書局.

- Wang, Zhongluo [王仲荦] (2007). Wei jin nan bei chao shi [History of Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties] 魏晋南北朝史. Beijing [北京], Zhonghua shu ju [China Press] 中华书局.

- Rubie Sharon Watson (1991). Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. University of California Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7.

- Tang, Qiaomei (May 2016). Divorce and the Divorced Woman in Early Medieval China (First through Sixth Century) (PhD). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. pp. 151, 152, 153.

- Papers on Far Eastern History. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. 1983. p. 86.

- Hinsch, Bret (2018). Women in Early Medieval China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 97. ISBN 978-1538117972.

- Hinsch, Bret (2016). Women in Imperial China. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 72. ISBN 978-1442271661.

- Lee, Jen-der (2014). "9. Crime and Punishment The Case of Liu Hui in the Wei Shu". In Swartz, Wendy; Campany, Robert Ford; Lu, Yang; Choo, Jessey (eds.). Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 156–165. ISBN 978-0231531009.

- Australian National University. Dept. of Far Eastern History (1983). Papers on Far Eastern History, Volumes 27-30. Australian National University, Department of Far Eastern History. pp. 86, 87, 88.

- China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

Xiao Baoyin.

- Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature (vol.3 & 4): A Reference Guide, Part Three & Four. BRILL. 22 September 2014. pp. 1566–. ISBN 978-90-04-27185-2.

- China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

sima.

- Holcombe, Charles (2011). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-521-73164-5.

- Chen, Yinke [陳寅恪], 1943, Tang dai zheng zhi shi shu lun gao [Manuscript of Discussions on the Political History of the Tang dynasty] 唐代政治史述論稿. Chongqing [重慶], Shang wu [商務].

- Chen, Yinke [陳寅恪] and Tang, Zhenchang [唐振常], 1997, Tang dai zheng zhi shi shu lun gao [Manuscript of Discussions on the Political History of the Tang dynasty] 唐代政治史述論稿. Shanghai [上海], Shanghai gu ji chu ban she [Shanghai Ancient Literature Press] 上海古籍出版社.

- Barbara Bennett Peterson (2000). Barbara Bennett Peterson (ed.). Notable women of China: Shang dynasty to the early twentieth century (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7656-0504-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- Watt, James C.Y. China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Comp. An Jiayao, Angela F. Howard, Boris I. Marshak, Su Bai, and Zhao Feng. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004. Print.

- Laursen, Sarah (2011). Leaves That Sway: Gold Xianbei Cap Ornaments from Northeast China (PhD). UPenn Repository.

- Bunker, Emma C.; Sun, Zhixin (2002). Watt, James (ed.). Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes: The Eugene V. Thaw and Other New York Collections. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09688-7 – via Google Books.

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2003). "Han and Xiongnu: A Reexamination of Cultural and Political Relations (I)". Monumenta Serica. 51: 55–236. JSTOR 40727370.

- Dien, Albert E. (1986). "The Stirrup and Its Effect on Chinese Military History". Ars Orientalis. 16: 33–56. JSTOR 4629341.

- Dien, Albert E. (2007). Six Dynasties Civilization. New Haven, CT: Yale UP. ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8.

- Janhunen 2006, pp. 405-6.

- Holcombe, Charles (2013). "The Xianbei in Chinese History". Early Medieval China. 19: 1–38 [pp. 4–5]. doi:10.1179/1529910413Z.0000000006.

- Wang, Pengling (2018). Linguistic Mysteries of Ethnonyms in Inner Asia. Lexington Books. ISBN 1498535283.

- Wang, Pengling (2018). Linguistic Mysteries of Ethnonyms in Inner Asia. Lexington Books. pp. 104–105. ISBN 1498535283.

- Tumen, D. (2011). "Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia" (PDF). 東洋學 檀國大學校 東洋學硏究所 [Dankook University Asia Research Series]. 49: 23–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Yu et al. 2006, p. 6244, Table 1.

- Yu et al. 2006, p. 6244.

- Yu et al. 2006, p. 6242, 6244-6245.

- Yu et al. 2014, p. 310, Table 2.

- Wang al. 2007, p. 404.

- Wang al. 2007, p. 408, Table 3.

- Li et al. 2018, p. 1.

- Lü, Jianfu [呂建福], 2002. Tu zu shi [The Tu History] 土族史. Beijing [北京], Zhongguo she hui ke xue chu ban she [Chinese Social Sciences Press] 中囯社会科学出版社.

- Liaoning Provincial Nationalities Research Institute 辽宁省民族硏究所 (1986). Xibo zu shi lun kao [Examination on the History of the Xibo Nationality] 锡伯族史论考. Shenyang, Liaoning Nationalities Press

- Ji Nan [嵇南] and Wu Keyao [吳克尧] (1990). Xibo zu [Xibo Nationality] 锡伯族. Beijing, Nationalities Press.

- "성씨정보 | 남원독고씨 (南原 獨孤氏) - 시조(始祖) : 독고신(獨孤信) :+: Www.Surname.iNFO".

- "성씨정보 | 독고씨 (獨孤氏) - 인구 분포도 (人口 分布圖) :+: Www.Surname.iNFO".

- http://www.rootsinfo.co.kr/info/roots/view_bon.php?H=%D4%BC%CD%B5&S=%B5%B6%B0%ED

- hyo.djjunggu.go.kr/html/hyo/museum

- https://familysearch.org/search/catalog/1207177?availability=Family%20History%20Library

- "성씨정보 | 남원 독고씨 (南原獨孤氏) - 상계 세계도(上系世系圖) :+: Www.Surname.iNFO".

- "성씨정보 | 남원독고씨 (南原 獨孤氏) - 인구 분포도 (人口 分布圖) :+: Www.Surname.iNFo = www.Surname.KR".

Bibliography

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007), A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms, Brill

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2010), Imperial Warlord, Brill

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2017), Fire Over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty, 23-220 AD, Brill

- Holcombe, Charles (2014), The Xianbei in Chinese History

- Li, Jiawei; et al. (August 2018). "The genome of an ancient Rouran individual reveals an important paternal lineage in the Donghu population". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 166 (4). doi:10.1002/ajpa.23491. PMID 29681138. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Twitchett, Denis (2008), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, Cambridge University Press

- Janhunen (27 January 2006). The Mongolic Languages. Routledge. p. 393. ISBN 978-1-135-79690-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wang, Haijing; et al. (November 2007). "Molecular genetic analysis of remains from Lamadong cemetery, Liaoning, China". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 134 (3): 404–411. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20685. PMID 17632796. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Yu, Changchun; et al. (October 20, 2006). "Genetic analysis on Tuoba Xianbei remains excavated from Qilang Mountain Cemetery in Qahar Right Wing Middle Banner of Inner Mongolia". The FEBS Journal. Wiley. 580 (26): 6242–6246. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.030. PMID 17070809. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Yu, C.-C.; et al. (April 6, 2014). "Genetic analyses of Xianbei populations about 1,500–1,800 years old". Russian Journal of Genetics. Springer. 50 (3): 308–314. doi:10.1134/S1022795414030119. ISSN 1022-7954. PMID 17070809. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

External links

- 鮮卑語言 The Xianbei language (Chinese Traditional Big5 code page) via Internet Archive