Beiyang Army

The Beiyang Army (Pei-yang Army; simplified Chinese: 北洋军; traditional Chinese: 北洋軍; pinyin: Běi Yáng Jūn; Wade–Giles: Pei3-yang2 Chün1; lit.: 'Northern Ocean Army'), named after the Beiyang region,[1] was a powerful, Western-style Imperial Chinese Army established by the Qing Dynasty government in the late 19th century. It was the centerpiece of a general reconstruction of Qing China's military system. The Beiyang Army played a major role in Chinese politics for at least three decades and arguably right up to 1949. It made the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 possible, and, by dividing into warlord factions known as the Beiyang Clique (Pei-yang Clique; simplified Chinese: 北洋军阀; traditional Chinese: 北洋軍閥; pinyin: Běiyáng Jūnfá; Wade–Giles: Pei3-yang2 Chün1-fa2), ushered in a period of regional division.

| Beiyang Army | |

|---|---|

| 北洋軍 | |

The military symbol based on the Five Races Under One Union flag was replaced after unification in 1928 because of its association with Beiyang warlords | |

| Country | |

| Role | New Army |

| Size | 20,000 (1901) 60,000 (1905) |

| Garrison/HQ | Tianjin |

| Flag of China (1912-1928) | .svg.png) |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Yuan Shikai Yinchang Feng Guozhang |

The Beiyang Army had its origins in the Newly Created Army established in late 1895 under Yuan Shikai's command, which rapidly expanded after 1901 with new recruits and by incorporating other forces. By 1906 it had six divisions and was the most advanced army under the command of the Qing dynasty.

Origins under Li Hongzhang (to 1900)

The beginning of the Beiyang Army could be traced back to Li Hongzhang's Huai Army, which was raised to quell the Taiping Rebellion. Unlike the traditional Green Standard or Banner forces of the Qing, the Huai Army was largely a militia army based on personal, rather than institutional, loyalties. The Huai Army was at first equipped with a mixture of traditional and modern weapons. Its creator, Li Hongzhang, used the customs and tax revenues of the five provinces under his control in the 1880s and 1890s to modernize segments of the Huai Army, and to build a modern navy (the Beiyang Fleet).

It is around this time that the term "Beiyang Army" began to be used to refer to the military forces under his control. The term, meaning literally "Northern Ocean",[1] refers to the customs and excise revenues collected in the Beiyang region (the northern coastal provinces of Zhili, Shandong and Liaoning, surrounding the imperial capital of Peking), which were used first to fund the Beiyang Fleet and later the Beiyang Army.[1] However, funding was usually irregular and training by no means systematic.[2][3][4][5][6][7] By the early 1890s, these modernized units established by Li Hongzhang that were known as the Beiyang Army were the best military forces that the Qing dynasty could field. Their first action was the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), which was fought almost entirely by the Beiyang Army, unsupported by the forces of other provinces. But Japan's German-styled conscript army, led by academy trained professional officers, handily defeated the Beiyang Army. The Qing government sued for peace after six months of uninterrupted Japanese victories.[8]

Yuan Shikai's ascendancy (1901–1908)

Li Hongzhang died in 1901 and was replaced by Yuan Shikai, who took on Li's appointment as Viceroy of Zhili and as Minister of Beiyang (北洋通商大臣). Yuan had been given command of the brigade-sized New Created Army in 1895, which had 7,000 soldiers at the time and would expand to 20,000 by 1902. By the autumn of 1905 the Beiyang Army consisted of six divisions of 10,000 men each. It was organized into infantry, artillery, cavalry, and auxiliary troops, as well as maintenance and engineering. A seventh division was established in 1907 at Jiangsu. The Army's training instructors were mostly Japanese and Germans.[9]

Yuan Shikai oversaw the reform of Qing military institutions after 1901 as the government tried to create a national army. He founded the Baoding Military Academy, which allowed him to expand the Beiyang Army, along with several other military schools and officer training academies. With the creation of the Commission for Army Reorganisation in December 1903, the Beiyang Army became the model on which the military forces of other provinces should be standardized. Although some units were based in the three northeastern provinces in Manchuria, the main base of the Beiyang Army was at Baoding, near Tianjin. In the early 1900s, a department for military administration was also created for the Beiyang divisions to manage logistics, which was divided into several branches. It was the opinion of foreign observers that the Beiyang Army was the largest, best equipped and best trained military force in China at the time.[9]

The Beiyang Army under Qing control (1909–1910)

The Empress Dowager Cixi died on 15 November 1908 and named the three-year-old Puyi as the new emperor. The new regent and father of Puyi, Prince Chun (醇親王), had Yuan Shikai dismissed the next year. Yuan bided his time in retirement, carefully maintaining his network of personal contacts in the Beiyang Army. At the time of the 1911 Revolution, command of the Beiyang Army was supposedly in the hands of the Qing minister Yinchang. In reality, Yuan Shikai still had the ability to manipulate it due to the loyalties of its officers to him personally. Four divisions were located in Zhili, the 3rd Division being in northeast China and the 5th Division in Shandong. Almost all the officers were ethnically Chinese, many of whom were returned students from Japan. Armament was not standardized, but was better in that respect than either before or later. Most of the infantry were armed with either the standard 1896 Japanese Type 30 rifle or the Mauser 7.9 mm.

The 1911 Revolution

The events of the revolution demonstrated that the Beiyang Army, which formed the core of the 36-division New Army, was absolutely the dominant military force within China. Controlling the fragmented loyalties of its formations was the key to political power in post–1911 China. The insurrection that actually set off the 1911 Revolution took place in Wuchang on 10 October. Four days later, the Qing court organized the New Armies in the north, and particularly the Beiyang Army, into three forces: the First Army, which would be sent to fight at Wuchang under the command of Army Minister Yinchang, the Second Army, which would act as a reserve force and would be sent to the front as needed, under the command of Feng Guozhang, and the Third Army, which would defend the capital, under Zaitao. The First and Second armies consisted of about 25,000 men each, or two divisions. The First included elements from the second, fourth, sixth divisions of the Beiyang army, which were the Qing government's crack troops, trained by Yuan Shikai.[10]

Their order of battle in October 1911 was as follows:[10][11]

- 1st Army (Yinchang, later Yuan Shikai)

- 4th Division (Wu Fengling, later Chen Guangyuan)

- 7th Brigade (Chen Guangyuan)

- 8th Brigade (Wang Yujia)

- 3rd Brigade (Wang Zhanyuan) — of the 2nd Division.

- 11th Brigade (Li Chun) — of the 6th Division.

- 4th Division (Wu Fengling, later Chen Guangyuan)

- 2nd Army (Feng Guozhang)

- 5th Division (Zhang Yongcheng)

- 5th Brigade (Lu Yongxiang) — of the 3rd Division.

- 39th Brigade (Wu Zhenxiang) — of the 20th Division, which was formed in January 1910.

- 2nd Mixed Brigade (Wang Ruxian, later Lan Tianwei) — formed from 2nd and 4th Divisions.

- 3rd Army (Zaitao)

- 1st Division

- Capital Guards (Zaifeng, Prince Chun) — Manchu bannermen trained by Yuan Shikai, under the prince-regent's direct command.

The Second Army was never formed as a functional military unit as a result of mutiny, and thus never was sent to the front to assist the First Army. The formations were abolished in early December 1911.[12]

On 12 October Yinchang was ordered to take two Beiyang Army divisions (the First Army) down the Beijing-Hankou Railway to suppress the uprising at Wuchang. He attacked the revolutionary army commanded by Huang Xing on 27 October. Covered by their own field artillery and the guns of the imperial fleet, the Beiyang infantry attacked with a cloud of skirmishers followed by a line of close-order company fronts. These textbook tactics were soon to be discredited in the intense fighting of the First World War, but against an undisciplined revolutionary force with no machine guns, they worked perfectly.

On that same day Yuan Shikai was ordered to take command of the forces at Wuchang. He refused, instead securing high commands for his two most trusted associates, Feng Guozhang and Duan Qirui. Fighting continued in Hubei for another month as Yuan negotiated with the dynasty and the revolutionaries using the Beiyang Army as a weapon of coercion. The end result was that he was elected provisional President of the Republic of China.

Beiyang clique in power (1911–15)

During the period 1911–15, Yuan Shikai remained the only man who could hold the Beiyang Army together. He and his followers strongly resisted any attempt by the Kuomintang (KMT) to insert outsiders into their chain of command. They negotiated a £25-million (sterling) loan from a five-power banking consortium to support the Beiyang Army, despite an uproar from the KMT. In 1913 Yuan Shikai appointed four of his loyal lieutenants as military governors in southern provinces: Duan Qirui in Anhui, Feng Guozhang in Jiangsu, Li Shun in Jiangxi and Tang Xiangming in Hunan. The unified Beiyang military clique now attained its maximum extent of territorial control. It exercised firm control over North China and the Yangtze River provinces. Throughout 1914 it supported Yuan in making revisions to the constitution to give himself treaty- and war-making powers as well as substantial emergency powers (the three commanders were nicknamed by the newspapers of the time as angel, tiger and dog. Angel was Duan Qirui, tiger Wang Shizhen and dog Feng Guozhang).

In December 1915 Yuan Shikai declared himself Emperor. This was opposed by almost all the generals and officers of the Beiyang Army, from Duan Qirui and Feng Guozhang on down. More importantly, many outlying provinces such as Yunnan openly opposed him. Yuan was forced to back down from his imperial designs. Both Duan and Feng refused to support him in power any further, and in the end the only prominent Beiyang general to remain loyal was the irrepressible Zhang Xun. Yuan died soon afterward. After his death the Beiyang Army split into cliques led by Yuan's principal protégés. Duan Qirui's Anhui clique and the Zhili clique, founded by Feng Guozhang but led after Feng's death by Cao Kun and Wu Peifu, were the principal Beiyang cliques. Disunited, the power of the Beiyang Army was challenged by provincial armies such as Yan Xishan's forces in Shanxi and Zhang Zuolin's Fengtian clique.

Fragmentation of the Beiyang army (1916–18)

Pressure from the Beiyang commanders prevented any political figure of the left taking power in the government of the Republic of China. For almost a decade after Yuan's death, the agenda of the leading Beiyang warlords was to reunify China by first reuniting the Beiyang Army and then conquering the lesser provincial armies.

For a period from mid-1916, the ultraconservative Beiyang Gen. Zhang Xun managed to maintain the unity of the army via collegial contacts and negotiation. As Yuan Shikai had done, the Beiyang generals used their military power to intimidate the parliament into passing legislation they wanted. Following a dispute with President Li Yuanhong over a loan from Japan in early 1917, Duan Qirui declared independence from the government along with most of the other Beiyang generals. Zhang Xun then occupied Beijing with his army, and on 1 July shocked the Chinese political world by proclaiming the restoration of the Qing dynasty. All the other generals condemned this and the restoration soon collapsed. The elimination of Zhang Xun soon afterwards destroyed the balance of power between the rival factions of Feng and Duan and inaugurated a decade of warlordism.

Feng Guozhang went to Beijing to assume the presidency after securing the appointment of his protégé as military commander in Jiangxi, Hubei and Jiangsu. These three provinces became the power bases of the Zhili military clique. Duan Qirui resumed his position as Prime Minister; his Anhui (sometimes called Anfu) clique dominated the Beijing area. Using Japanese funding to build up his so-called "War Participation Army", Duan continued to struggle with Feng Guozhang.

Feng was eventually eliminated from political life in 1918, when Xu Shichang, the Beiyang elder statesman, became President. His deputy Cao Kun replaced him as leader of the Zhili clique. At the end of World War I, Duan dominated Chinese representation at the Treaty of Versailles and used the Shanghai peace conference in 1919 to bring pressure on the non-Beiyang militarists supporting Sun Yat-sen's government in Guangzhou. He continued to receive Japanese funding for his army (renamed "National Defence Army"), for which he was willing to grant Japan legal succession to the German rights in Shandong (see May Fourth Movement).

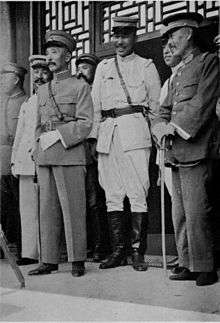

Group photo of warlord

Group photo of warlord Cavalry parade

Cavalry parade Infantly parade

Infantly parade Troop march

Troop march Mountain gun of Fengtian army

Mountain gun of Fengtian army Heavy machine gun

Heavy machine gun Howitzer

Howitzer FT-1701 of Fengtian Army

FT-1701 of Fengtian Army

High warlordism (1919–1925)

Before May–June 1919, some combination of fighting and negotiation among the major Beiyang leaders was expected to lead to military unification, which in turn would permit the restoration of the constitutional political processes that Yuan Shikai had disrupted. By 1919 the three major northern military cliques had cemented, two of them--Anhui and Zhili—directly from the Beiyang Army and the third, Fengtian under Gen. Zhang Zuolin, from an amalgamation of Beiyang and local troops. They and their imitators on a smaller scale were willing to get money and arms from any source in order to survive, and the weaker factions would combine against the stronger.

The history of the major warlord wars down to 1925 recount the failure of any of the military commanders in China to centralise political and military power to any degree. In a situation resembling the period of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms, most of South China remained beyond Beiyang control, to become the incubator for both the KMT and Communist Party of China movements.

Northern Expedition

The Kuomintang established the National Revolutionary Army with the help of the Soviet Union and Communist Party of China. Chiang Kai-shek then launched the Northern Expedition in 1926 in an attempt to bring the warlords under his control. Some warlords of the Beiyang Army were defeated by Chiang's forces, and the National Revolutionary Army gradually became dominant in China. The warlord era would be officially ended by 1928, when most of the warlords were either defeated or allied with the Kuomintang, although it was often in name only. The Chinese Civil War that had resulted from a fallout between Chiang and the Communists was already underway by this time. In 1930 the Central Plains War began after some of the warlords allied with the Kuomintang became disenchanted and attempted to overthrow Chiang. They weren't successful, but lack of cooperation and rivalry continued to plague China through much of the years following, eventually leading to the demise of Chiang's regime in the Chinese Civil War in 1949.

See also

- Beiyang government

- Military history of China

- New Army

- History of the Republic of China

- Whampoa Military Academy

References

Citations

- Yuan Shikai and the Significance of his Troop Training at Xiaozhan, Tianjin, 1895–1899, Hong Zhang, The Chinese Historical Review Volume 26, 2019 - Issue 1

- Baker (1894), p. 162

- "CHINA AND JAPAN". The West Australian. 10 (2, 692). Western Australia. 1 October 1894. p. 6. Retrieved 18 May 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Paine (2005), p. 156

- Lachlan (2012), p. 568

- Fairbank (1978), p. 269

- Adams (1931), p. 19

- Japan and the Illustrated London news: complete record of reported events, 1853-1899

- Schillinger (2016), pp. 29-33

- Esherick (2013), pp. 215—216

- Esherick (2013), pp. 219—222

- Esherick (2013), p. 223

Bibliography

- Baker, John James (1894). The Spectator. London: F.C. Westley.

- Paine, S. C. M. (11 April 2005). The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61745-1.

- McLachlan, Grant (11 November 2012). Sparrow: A Chronicle of Defiance: The story of The Sparrows – Battle of Britain gunners who defended Timor as part of Sparrow Force during World War II. Klaut. ISBN 978-0-473-22623-7.

- Fairbank, John King (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800-1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- Adams, Herbert Baxter Adams (1931). Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science: Extra volumes. Johns Hopkins Press.

- Esherick, Joseph W.; Wei, C.X. George (2013). China: How the Empire Fell. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-83101-7.

- Schillinger, Nicolas (2016). The Body and Military Masculinity in Late Qing and Early Republican China: The Art of Governing Soldiers. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1498531689.