Eight Banners

The Eight Banners (in Manchu: ᠵᠠᡴᡡᠨ

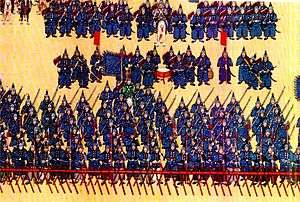

ᡤᡡᠰᠠ jakūn gūsa, Chinese: 八旗; pinyin: bāqí) were administrative and military divisions under the Later Jin and the Qing dynasty of China into which all Manchu households were placed. In war, the Eight Banners functioned as armies, but the banner system was also the basic organizational framework of all of Manchu society. Created in the early 17th century by Nurhaci, the banner armies played an instrumental role in his unification of the fragmented Jurchen people (who would later be renamed the "Manchu" under Nurhaci's son Hong Taiji) and in the Qing dynasty's conquest of the Ming dynasty.

| Eight Banners | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Later Jin Qing dynasty |

| Type | Army, administrative division |

| Engagements | Later Jin invasion of Joseon Qing conquest of Ming Qing invasion of Joseon |

| Eight Banners | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 八旗 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᠵᠠᡴᡡᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ | ||||||||||

| Romanization | jakūn gūsa | ||||||||||

As Mongol and Han forces were incorporated into the growing Qing military establishment, the Mongol Eight Banners and Han Eight Banners were created alongside the original Manchu banners. The banner armies were considered the elite forces of the Qing military, while the remainder of imperial troops were incorporated into the vast Green Standard Army. Membership in the banners became hereditary, and bannermen were granted land and income. After the defeat of the Ming dynasty, Qing emperors continued to rely on the Eight Banners in their subsequent military campaigns. After the Ten Great Campaigns of the Qianlong Emperor, the quality of banner troops gradually decreased, and by the 19th century the task of defending the empire had largely fallen upon regional armies such as the Xiang Army. Over time, the Eight Banners became synonymous with Manchu identity even as their military strength vanished.

History

Establishment

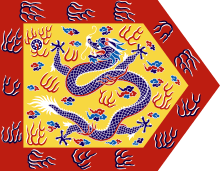

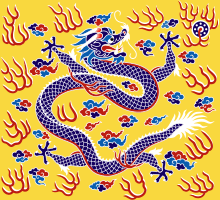

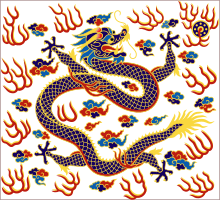

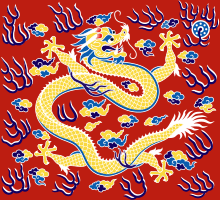

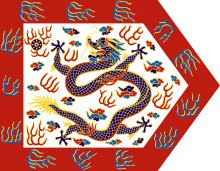

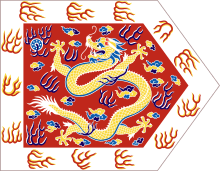

Initially, Nurhaci's forces were organized into small hunting parties of about a dozen men related by blood, marriage, clan, or place of residence, as was the typical Jurchen custom. In 1601, with the number of men under his command growing, Nurhaci reorganized his troops into companies of 300 households. Five companies made up a battalion, and ten battalions a banner. Four banners were originally created: Yellow, White, Red, and Blue, each named after the color of its flag. By 1614, the number of companies had grown to around 400.[1] In 1615, the number of banners was doubled through the creation of "bordered" banners. The troops of each of the original four banners would be split between a plain and a bordered banner.[2][3] The bordered variant of each flag was to have a red border, except for the Bordered Red Banner, which had a white border instead.

The banner armies expanded rapidly after a string of military victories under Nurhaci and his successors. Beginning in the late 1620s, the Jurchens incorporated allied and conquered Mongol tribes into the Eight Banner system. In 1635, Hong Taiji, son of Nurhaci, renamed his people from Jurchen to Manchu. That same year the Mongols were separated into the Mongol Eight Banners (Manchu: ᠮᠣᠩᡤᠣ

ᡤᡡᠰᠠ, monggo gūsa; Chinese: 八旗蒙古; pinyin: bāqí ménggǔ).[3]

Invasions of Korea

Under Hong Taiji, the banner armies participated in two invasions of Korea under the Joseon dynasty, first in 1627 and again in 1636. As a consequence, Korea was forced to end its former relationship with the Ming dynasty and become a Qing tributary instead.

Conquest of the Ming

Initially, Chinese troops were incorporated into the existing Manchu Banners. When Hong Taiji captured Yongping in 1629, a contingent of artillerymen surrendered to him. In 1631, these troops were organized into the so-called Old Han Army under the Chinese commander Tong Yangxing.[4] These artillery units were used decisively to defeat Ming general Zu Dashou's forces at the siege of Dalinghe that same year.[5][6] In 1636, Hong Taiji proclaimed the creation of the Qing dynasty.

Between 1637 and 1642,[7][8] the Old Han Army, mostly made up of Liaodong natives who had surrendered at Yongping, Fushun, Dalinghe, etc., were organized into the Han Chinese Eight Banners (Manchu: ᠨᡳᡴᠠᠨ

ᠴᠣᠣᡥᠠ nikan cooha or ᡠᠵᡝᠨ

ᠴᠣᠣᡥᠠ ujen cooha; Chinese: 八旗漢軍; pinyin: bāqí hànjūn). The original Eight Banners were thereafter referred to as the Manchu Eight Banners (Manchu: ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ

ᡤᡡᠰᠠ, manju gūsa; Chinese: 八旗滿洲; pinyin: bāqí mǎnzhōu). Although still called the "Eight Banners" in name, there were now effectively twenty-four banner armies, eight for each of the three main ethnic groups (Manchu, Mongol, and Chinese).[3]

Among the Banners gunpowder weapons, such as muskets and artillery, were specifically wielded by the Chinese Banners.[9]

After Hong Taiji's death, Dorgon, commander of the Solid White Banner, became regent. He quickly purged his rivals and took control over Hong Taiji's Solid Blue Banner. By 1644, an estimated two million people were living in the Eight Banners system.[10] That year, the Chinese rebel Li Zicheng captured Beijing and the last emperor of the Ming dynasty, Chongzhen, committed suicide. Dorgon and his bannermen joined forces with Ming defector Wu Sangui to defeat Li at the Battle of Shanhai Pass and secure Beijing for the Qing. The young Shunzhi Emperor was then enthroned in the Forbidden City.[11]

Ming defectors played a major role in the Qing conquest of China. Han Chinese generals who defected to the Manchus were often given women from the Imperial Aisin Gioro family in marriage while the ordinary soldiers who defected were given non-royal Manchu women as wives. The Qing differentiated between Han bannermen and ordinary Han civilians. Han bannermen were made out of Han Chinese who defected to the Qing up to 1644 and joined the Eight Banners, giving them social and legal privileges in addition to being acculturated to Manchu culture. So many Han defected to the Qing and swelled up the ranks of the Eight Banners that ethnic Manchus became a minority within the Banners, making up only 16% in 1648, with Han bannermen dominating with 75% and Mongol Bannermen making up the rest.[12][13] It was this multi-ethnic force, in which Manchus were only a minority, which conquered China for the Qing.[14] Hong Taiji recognized that Ming Han Chinese defectors were needed by the Manchus in order to assist in the conquest of the Ming, explaining to other Manchus why he needed to treat the Ming defector General Hung Ch'eng-ch'ou leniently.[15]

The Qing showed in propaganda targeted towards the Ming military that the Manchus valued military skills to get them to defect to the Qing, since the Ming civilian political system discriminated against the military.[16] The three Liaodong Han Bannermen officers who played a massive role in the conquest of southern China from the Ming were Shang Kexi, Geng Zhongming, and Kong Youde and they governed southern China autonomously as viceroys for the Qing after their conquests.[17] Normally the Manchu Bannermen acted as reserve forces while the Qing foremost used defected Han Chinese troops to fight as the vanguard during their conquest of China.[18]

The Liaodong Han Chinese military frontiersmen were prone to mixing and acculturating with (non-Han) tribesmen.[19] The Mongol officer Mangui served in the Ming military and fought the Manchus, dying in battle against a Manchu raid.[20][21][22] The Jurchen Manchus accepted and assimilated Han Chinese soldiers who defected.[23] Liaodong Han Chinese transfrontiersmen soldiers acculturated to Manchu culture and used Manchu names. Manchus lived in cities with walls surrounded by villages and adopted Chinese style agriculture before the Qing conquest of the Ming.[24] The Han Chinese transfrontismen abandoned their Han Chinese names and identities and Nurhaci's secretary Dahai might have been one of them.[25]

There were not enough ethnic Manchus to conquer China, so they relied on defeating and absorbing Mongols, and more importantly, adding Han Chinese to the Eight Banners.[26] The Manchus had to create an entire "Jiu Han jun" (Old Han Army) due to the massive number of Han Chinese soldiers who were absorbed into the Eight Banners by both capture and defection, Ming artillery was responsible for many victories against the Manchus, so the Manchus established an artillery corps made out of Han Chinese soldiers in 1641 and the swelling of Han Chinese numbers in the Eight Banners led in 1642 of all Eight Han Banners being created.[27] It was defected Ming Han Chinese armies which conquered southern China for the Qing.[28]

When Dorgon ordered Han civilians to vacate Beijing's inner city and move to the outskirts, he resettled the inner city with the Bannermen, including Han Chinese bannermen, later, some exceptions were made to allowing to reside in the inner city Han civilians who held government or commercial jobs.[29]

The Qing relied on the Green Standard soldiers, made out of defected Han Chinese Ming military forces who joined the Qing, in order to help rule northern China.[30] It was Green Standard Han Chinese troops who actively military governed China locally while Han Chinese Bannermen, Mongol Bannermen, and Manchu Bannermen who were only brought into emergency situations where there was sustained military resistance.[31]

Manchu Aisin Gioro princesses were also married to Han Chinese official's sons.[32]

The Manchu Prince Regent Dorgon gave a Manchu woman as a wife to the Han Chinese official Feng Quan,[33] who had defected from the Ming to the Qing. The Manchu queue hairstyle was willingly adopted by Feng Quan before it was enforced on the Han population and Feng learned the Manchu language.[34]

To promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree from Shunzhi allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Manchu women from the Banners with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners or the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners. It was only later in the dynasty that these policies allowing intermarriage were done away with.[35][36] The decree was formulated by Dorgon.[29]

The Guangzhou massacre of Ming loyalist Han forces and civilians in 1650 by Qing forces, was entirely carried out by Han Chinese Bannerman led by Han Chinese Generals Shang Kexi and Geng Jimao.

The Manchus sent Han Bannermen to fight against Koxinga's Ming loyalists in Fujian.[37] The Qing carried out a massive depopulation policy clearances forcing people to evacuated the coast in order to deprive Koxinga's Ming loyalists of resources, this has led to a myth that it was because Manchus were "afraid of water". In Fujian, it was Han Bannermen who were the ones carrying out the fighting and killing for the Qing and this disproved the entirely irrelevant claim that alleged fear of the water on part of the Manchus had to do with the coastal evacuation and clearances.[38] Even though a poem refers to the soldiers carrying out massacres in Fujian as "barbarian", both Han Green Standard Army and Han Bannermen were involved in the fighting for the Qing side and carried out the worst slaughter.[39] 400,000 Green Standard Army soldiers were used against the Three Feudatories besides 200,000 Bannermen.[40]

Revolt of the Three Feudatories

In the Revolt of the Three Feudatories Manchu Generals and Bannermen were initially put to shame by the better performance of the Han Chinese Green Standard Army, who fought better than them against the rebels and this was noted by the Kangxi Emperor, leading him to task Generals Sun Sike, Wang Jinbao, and Zhao Liangdong to lead Green Standard soldiers to crush the rebels.[41] The Qing thought that Han Chinese were superior at battling other Han people and so used the Green Standard Army as the dominant and majority army in crushing the rebels instead of Bannermen.[42] In northwestern China against Wang Fuchen, the Qing put Bannermen in the rear as reserves while they used Han Chinese Green Standard Army soldiers and Han Chinese Generals like Zhang Liangdong, Wang Jinbao, and Zhang Yong as the primary military forces, considering Han troops as better at fighting other Han people, and these Han generals achieved victory over the rebels.[43] Sichuan and southern Shaanxi were retaken by the Han Chinese Green Standard Army under Wang Jinbao and Zhao Liangdong in 1680, with Manchus only participating in dealing with logistics and provisions.[44] 400,000 Green Standard Army soldiers and 150,000 Bannermen served on the Qing side during the war.[44] 213 Han Chinese Banner companies, and 527 companies of Mongol and Manchu Banners were mobilized by the Qing during the revolt.[9]

The Qing forces were crushed by Wu from 1673–1674.[45] The Qing had the support of the majority of Han Chinese soldiers and Han elite against the Three Feudatories, since they refused to join Wu Sangui in the revolt, while the Eight Banners and Manchu officers fared poorly against Wu Sangui, so the Qing responded with using a massive army of more than 900,000 Han Chinese (non-Banner) instead of the Eight Banners, to fight and crush the Three Feudatories.[46] Wu Sangui's forces were crushed by the Green Standard Army, made out of defected Ming soldiers.[47]

Territorial expansion

Koxinga's rattan shield troops became famous for fighting and defeating the Dutch in Taiwan. After the surrender of Koxinga's former followers on Taiwan, Koxinga's grandson Zheng Keshuang and his troops were incorporated into the Eight Banners. His rattan shield soldiers (Tengpaiying) 藤牌营 were used against the Russian Cossacks at Albazin.

Under the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors, the Eight Banners participated in a series of military campaigns to subdue Ming loyalists and neighboring states. In the Qianlong Emperor's celebrated Ten Great Campaigns, the banner armies fought alongside troops of the Green Standard Army, expanding the Qing empire to its greatest territorial extent. Though partly successful, the campaigns were a heavy financial burden on the Qing treasury, and exposed weaknesses in the Qing military. Many bannermen lost their lives in the Burma campaign, often as the result of tropical diseases, to which they had little resistance.

Later history

Although the banners were instrumental in the Qing Empire takeover of China proper in the 17th century from the Ming dynasty, they began to fall behind rising Western powers in the 18th century. By the 1730s, the traditional martial spirit had been discarded, as the well-paid Bannerman spent their time gambling and theatergoing. Subsidizing the 1.5 million men, women and children in the system was an expensive proposition, compounded by embezzlement and corruption.

Destitution in the northeastern garrisons led many Manchu Bannermen to abandon their posts and in response the Qing government either sentenced them with penal slavery or death.[48]

In the 19th century, the Eight Banners and Green Standard troops proved unable to put down the Taiping Rebellion and Nian Rebellion on their own. Regional officials like Zeng Guofan were instructed to raise their own forces from the civilian population, leading to the creation of the Xiang Army and the Huai Army, among others. Along with the Ever Victorious Army of Frederick Townsend Ward, it was these warlord armies (known as yongying) who finally succeeded in restoring Qing control in this turbulent period.

John Ross, a Scots missionary who served in Manchuria in the 19th century, wrote of the bannermen, "Their claim to be military men is based on their descent rather than on their skill in arms; and their pay is given them because of their fathers' prowess, and not at all from any hopes of their efficiency as soldiers. Their soldierly qualities are included in the accomplishments of idleness, riding, and the use of the bow and arrow, at which they practice on a few rare occasions each year."[49]

During the Boxer Rebellion, 1899–1901, 10,000 Bannermen were recruited from the Metropolitan Banners and given modernized training and weapons. One of these was the Hushenying. Many Manchu Bannermen in Beijing supported the Boxers and shared their anti-foreign sentiment.[50] The Manchu Bannermen were devastated by the fighting during the Boxer Rebellion, sustaining enormous casualties during the war and subsequently being driven into desperate poverty.[51]

Zhao Erfeng and Zhao Erxun were two important Han Bannermen in the late Qing.

By the late 19th century, the Qing Dynasty began training and creating New Army units based on Western training, equipment and organization. Nevertheless, the banner system remained in existence until the fall of the Qing in 1911, and even beyond, with a rump organization continuing to function until the expulsion of Puyi (the former Xuantong emperor) from the Forbidden City in 1924.

At the end of the Qing dynasty, all members of the Eight Banners, regardless of their original ethnicity, were considered by the Republic of China to be Manchu.

Han Bannermen became an elite political class in Fengtian province in the late Qing period and into the Republican era.[52]

In addition to sending Han exiles convicted of crimes to Xinjiang to be slaves of Banner garrisons there, the Qing also practiced reverse exile, exiling Inner Asian (Mongol, Russian and Muslim criminals from Mongolia and Inner Asia) to China proper where they would serve as slaves in Han Banner garrisons in Guangzhou. Russian, Oirats and Muslims (Oros. Ulet. Hoise jergi weilengge niyalma) such as Yakov and Dmitri were exiled to the Han banner garrison in Guangzhou.[53] In the 1780s after the Muslim rebellion in Gansu started by Zhang Wenqing (張文慶) was defeated, Muslims like Ma Jinlu (馬進祿) were exiled to the Han Banner garrison in Guangzhou to become slaves to Han Banner officers.[54] The Qing code regulating Mongols in Mongolia sentenced Mongol criminals to exile and to become slaves to Han bannermen in Han Banner garrisons in China proper.[55]

Organization

At the highest level, the eight banners were categorized according to two groupings. The three "upper" banners (both Yellow Banners and the Plain White Banner) were under the nominal command of the emperor himself, whereas the five "lower" banners were commanded by others. The banners were also split into a "left wing" and a "right wing" according to how they would be arrayed in battle. In Beijing, the left wing occupied the eastern banner neighborhoods and the right wing occupied the western ones.[56]

The smallest unit in a banner army was the company, or niru (Chinese: 佐領; pinyin: zuǒlǐng), composed nominally of 300 soldiers and their families. The term niru means "arrow" in the Manchu language, and was originally the Manchu name for a hunting party, which would be armed with bows and arrows. 15 companies (4,500 men) made up one jalan (Chinese: 參領; pinyin: cānlǐng). 4 jalan constituted a gūsa (banner), with a total of 60 companies, or 18,000 men. The actual sizes often varied substantially from these standards.[10]

| gūsa | jalan | niru |

|---|---|---|

| ᡤᡡᠰᠠ | ᠵᠠᠯᠠᠨ | ᠨᡳᡵᡠ |

| Banner | English | Manchu | Mongolian | Chinese | L/R | U/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bordered Yellow Banner | ᡴᡠᠪᡠᡥᡝ ᠰᡠᠸᠠᠶᠠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ kubuhe suwayan gūsa |

ᠬᠥᠪᠡᠭᠡᠲᠦ ᠰᠢᠷᠠ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ köbegetü sir-a qosiɣu |

鑲黃旗 xiānghuángqí | Left | Upper |

|

Plain Yellow Banner | ᡤᡠᠯᡠ ᠰᡠᠸᠠᠶᠠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ gulu suwayan gūsa |

ᠰᠢᠯᠤᠭᠤᠨ ᠰᠢᠷᠠ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ siluɣun sir-a qosiɣu |

正黃旗 zhènghuángqí | Right | Upper |

|

Plain White Banner | ᡤᡠᠯᡠ ᡧᠠᠩᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ gulu šanggiyan gūsa |

ᠰᠢᠯᠤᠭᠤᠨ ᠴᠠᠭᠠᠨ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ siluɣun čaɣan qosiɣu |

正白旗 zhèngbáiqí | Left | Upper |

|

Plain Red Banner | ᡤᡠᠯᡠ ᡶᡠᠯᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ gulu fulgiyan gūsa |

ᠰᠢᠯᠤᠭᠤᠨ ᠤᠯᠠᠭᠠᠨ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ siluɣun ulaɣan qosiɣu |

正紅旗 zhènghóngqí | Right | Lower |

|

Bordered White Banner | ᡴᡠᠪᡠᡥᡝ ᡧᠠᠩᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ kubuhe šanggiyan gūsa |

ᠬᠥᠪᠡᠭᠡᠲᠦ ᠴᠠᠭᠠᠨ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ köbegetü čaɣan qosiɣu |

鑲白旗 xiāngbáiqí | Left | Lower |

|

Bordered Red Banner | ᡴᡠᠪᡠᡥᡝ ᡶᡠᠯᡤᡳᠶᠠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ kubuhe fulgiyan gūsa |

ᠬᠥᠪᠡᠭᠡᠲᠦ ᠤᠯᠠᠭᠠᠨ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ köbegetü ulaɣan qosiɣu |

鑲紅旗 xiānghóngqí | Right | Lower |

|

Plain Blue Banner | ᡤᡠᠯᡠ ᠯᠠᠮᡠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ gulu lamun gūsa |

ᠰᠢᠯᠤᠭᠤᠨ ᠬᠥᠬᠡ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ siluɣun köke qosiɣu |

正藍旗 zhènglánqí | Left | Lower |

|

Bordered Blue Banner | ᡴᡠᠪᡠᡥᡝ ᠯᠠᠮᡠᠨ ᡤᡡᠰᠠ kubuhe lamun gūsa |

ᠬᠥᠪᠡᠭᠡᠲᠦ ᠬᠥᠬᠡ ᠬᠣᠰᠢᠭᠤ köbegetü köke qosiɣu |

鑲藍旗 xiānglánqí | Right | Lower |

Ethnic composition

Initially, the banner armies were primarily made up of individuals from the various Manchu tribes. As new populations were incorporated into the empire, the armies were expanded to accommodate troops of different ethnicities. The banner armies would eventually encompass three principal ethnic components: the Manchus, the Han, and the Mongols, and various smaller ethnic groups, such as the Xibe, the Daur, and the Evenks.

When the Jurchens were reorganized by Nurhaci into the Eight Banners, many Manchu clans were artificially created as a group of unrelated people founded a new Manchu clan (mukun) using a geographic origin name such as a toponym for their hala (clan name).[57]

There were stories of Han migrating to the Jurchens and assimilating into Manchu Jurchen society and Nikan Wailan may have been an example of this.[58] The Manchu Cuigiya 崔佳氏 clan claimed that a Han Chinese founded their clan.[59] The Tohoro 托和啰 (Duanfang's clan) claimed Han Chinese origin.[60][61][62][63][64] The Han Chinese Banner Tong 佟 clan of Fushun in Liaoning falsely claimed to be related to the Jurchen Manchu Tunggiya 佟佳 clan of Jilin, using this false claim to get themselves transferred to a Manchu banner in the reign of the Kangxi emperor.[65]

The transfer of families from Han Banners or Bondservant status (booi) to Manchu Banners, switching their ethnicity from Han to Manchu was called Taiqi (抬旗) in Chinese. They would be transferred to the "upper three" Manchu Banners. It was a policy of the Qing to transfer to immediate families[66] (the brothers, father) of the mother of an Emperor into the upper three Manchu Banners and having "giya" 佳 appended to the end of their surname to Manchufy it.[60] It typically occurred in cases of intermarriage with the Qing Aisin Gioro Imperial family, and the close relatives (fathers and brothers) of the concubine or Empress would get promoted from the Han Banner to the Manchu Banner and become Manchu. The Han Bannerwoman Empress Xiaoyichun and her entire family were transferred to the Manchu Banners due to her status as the mother of an Emperor and their surname was change from Wei 魏 to Weigiya 魏佳.

The Qing said that "Manchu and Han are one house" 滿漢一家 and said that the difference was "not between Manchu and Han, but instead between Bannerman and civilian" 不分滿漢,但問旗民[67] or 但問旗民,不問滿漢.[68]

Select groups of Han Chinese bannermen were mass transferred into Manchu Banners by the Qing, changing their ethnicity from Han Chinese to Manchu. Han Chinese bannermen of Tai Nikan 台尼堪 (watchpost Chinese) and Fusi Nikan 撫順尼堪 (Fushun Chinese)[69] backgrounds into the Manchu banners in 1740 by order of the Qing Qianlong emperor.[70] It was between 1618-1629 when the Han Chinese from Liaodong who later became the Fushun Nikan and Tai Nikan defected to the Jurchens (Manchus).[71] These Han Chinese origin Manchu clans continue to use their original Han surnames and are marked as of Han origin on Qing lists of Manchu clans.[72][73][74][75]

Manchu families adopted Han Chinese sons from families of bondservant Booi Aha (baoyi) origin and they served in Manchu company registers as detached household Manchus and the Qing imperial court found this out in 1729. Manchu Bannermen who needed money helped falsify registration for Han Chinese servants being adopted into the Manchu banners and Manchu families who lacked sons were allowed to adopt their servant's sons or servants themselves.[76] The Manchu families were paid to adopt Han Chinese sons from bondservant families by those families. The Qing Imperial Guard captain Batu was furious at the Manchus who adopted Han Chinese as their sons from slave and bondservant families in exchange for money and expressed his displeasure at them adopting Han Chinese instead of other Manchus.[77] These Han Chinese who infiltrated the Manchu Banners by adoption were known as "secondary-status bannermen" and "false Manchus" or "separate-register Manchus", and there were eventually so many of these Han Chinese that they took over military positions in the Banners which should have been reserved for Manchus. Han Chinese foster-son and separate register bannermen made up 800 out of 1,600 soldiers of the Mongol Banners and Manchu Banners of Hangzhou in 1740 which was nearly 50%. Han Chinese foster-son made up 220 out of 1,600 unsalaried troops at Jingzhou in 1747 and an assortment of Han Chinese separate-register, Mongol, and Manchu bannermen were the remainder. Han Chinese secondary status bannermen made up 180 of 3,600 troop households in Ningxia while Han Chinese separate registers made up 380 out of 2,700 Manchu soldiers in Liangzhou. The result of these Han Chinese fake Manchus taking up military positions resulted in many legitimate Manchus being deprived of their rightful positions as soldiers in the Banner armies, resulting in the real Manchus unable to receive their salaries as Han Chinese infiltrators in the banners stole their social and economic status and rights. These Han Chinese infiltrators were said to be good military troops and their skills at marching and archery were up to par so that the Zhapu lieutenant general couldn't differentiate them from true Manchus in terms of military skills.[78] Manchu Banners contained a lot of "false Manchus" who were from Han Chinese civilian families but were adopted by Manchu bannermen after the Yongzheng reign. The Jingkou and Jiangning Mongol banners and Manchu Banners had 1,795 adopted Han Chinese and the Beijing Mongol Banners and Manchu Banners had 2,400 adopted Han Chinese in statistics taken from the 1821 census. Despite Qing attempts to differentiate adopted Han Chinese from normal Manchu bannermen the differences between them became hazy.[79] These adopted Han Chinese bondservants who managed to get themselves onto Manchu banner roles were called kaihu ren (開戶人) in Chinese and dangse faksalaha urse in Manchu. Normal Manchus were called jingkini Manjusa.

Commoner Manchu bannermen who were not nobility were called irgen which meant common, in contrast to the Manchu nobility o the "Eight Great Houses" who held noble titles.[80][81]

Jiang Xingzhou 姜興舟, a Han bannerman lieutenant from the Bordered Yellow Banner married a Muslim woman in Mukden during Qianlong's late reign. He fled his position due to fear of being punished for being a bannerman marrying a commoner woman. He was sentenced to death for leaving his official post but the sentence was commuted and he was not executed.[82][83]

In the late 19th century and early 1900s, intermarriage between Manchus and Han bannermen in the northeast increased as Manchu families were more willing to marry their daughters to sons from well off Han families to trade their ethnic status for higher financial status.[84]

Banner soldiers

From the time China was brought under the rule of the Qing dynasty, the banner soldiers became more professional and bureaucratized. Once the Manchus took over governing, they could no longer satisfy the material needs of soldiers by garnishing and distributing booty; instead, a salary system was instituted, ranks standardized, and the Eight Banners became a sort of hereditary military caste, though with a strong ethnic inflection. Banner soldiers took up permanent positions, either as defenders of the capital, Beijing, where roughly half of them lived with their families, or in the provinces, where some eighteen garrisons were established. The largest banner garrisons throughout most of the Qing dynasty were at Beijing, followed by Xi'an and Hangzhou. Sizable banner populations were also placed in Manchuria and at strategic points along the Great Wall, the Yangtze River and Grand Canal.

Prominent Bannermen

- Agui – participated in the Sino-Burmese War and the suppression of the Jinchuan hill peoples. Member of the Plain Blue Banner.

- Fuheng – commander in the Sino-Burmese War. Member of the Bordered Yellow Banner.

- Fuk'anggan – commander in the Sino-Nepalese War. Member of the Bordered Yellow Banner.

- Geng Zhongming – Ming dynasty warlord. Inducted into the Chinese Plain Yellow Banner after submitting to Qing.

- Li Yongfang – Ming dynasty frontier commander. Inducted into the Chinese Plain Blue Banner after surrendering to Qing.

- Shi Lang

- Zheng Keshuang – grandson of Koxinga. Inducted into the Chinese Plain Red Banner after surrendering to Qing.

- Zhu Zhiliang – a descendant of the Ming dynasty Imperial Family. Granted the title Marquis of Extended Grace and inducted into the Chinese Plain White Banner.

- Zu Dashou – Ming dynasty frontier commander. Inducted into the Chinese Plain Yellow Banner after surrendering to Qing.

See also

Notes

- Wakeman 1986, pp. 53–54.

- Wakeman 1986, p. 54.

- Elliott 2001, p. 59.

- Wakeman 1986, pp. 168–169.

- Wakeman 1986, pp. 182–183.

- Elliott 2006, p. 43.

- Frederic Wakeman (1 January 1977). Fall of Imperial China. Simon and Schuster. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-0-02-933680-9.

- Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0.

- Di Cosmo 2007, p. 23.

- Elliott 2006, p. 30.

- Wakeman 1986, pp. 257–313.

- Naquin 1987, p. 141.

- Fairbank & Goldman 2006, p. 146.

- Rawski 1991, p. 175.

- The Cambridge History of China: Pt. 1 ; The Ch'ing Empire to 1800. Cambridge University Press. 1978. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- Di Cosmo 2007, p. 6.

- Di Cosmo 2007, p. 7.

- Di Cosmo 2007, p. 9.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Oriens extremus. Kommissionverlag O. Harrasowitz. 1959. p. 137.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 478–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 480–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 481–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Anne Walthall (2008). Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History. University of California Press. pp. 154–. ISBN 978-0-520-25444-2.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 872–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 868–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Wang 2004, pp. 215–216 & 219–221.

- Walthall 2008, p. 140-141.

- [Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China p. 135.

- [Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China p. 198.

- [Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China p. 206.

- [Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China p. 307.

- Di Cosmo 2007, p. 24.

- Di Cosmo 2007, pp. 24–25.

- Di Cosmo 2007, p. 15.

- Di Cosmo 2007, p. 17.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- David Andrew Graff; Robin Higham (2012). A Military History of China. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-8131-3584-7.

- Pamela Kyle Crossley (1990). Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World. Princeton University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 0-691-00877-9.

- Ross 1891, p. 683.

- Crossley 1990, p. 174.

- Rhoads 2000, p. 80.

- Yoshiki Enatsu (2004). Banner Legacy: The Rise of the Fengtian Local Elite at the End of the Qing. Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-89264-165-9.

- Yongwei, MWLFZZ, FHA 03-0188-2740-032, QL 43.3.30 (April 26, 1778).

- Šande 善德 , MWLFZZ, FHA 03-0193-3238-046, QL 54.5.6 (May 30, 1789) and Šande , MWLFZZ, FHA 03-0193-3248-028, QL 54.6.30 (August 20, 1789).

- 1789 Mongol Code (Ch. 蒙履 Menggu lüli , Mo. Mongγol čaγaǰin-u bičig ), (Ch. 南省,給駐防爲 , Mo. emün-e-tü muji-dur čölegüljü sergeyilen sakiγči quyaγ-ud-tur boγul bolγ-a ). Mongol Code 蒙例 (Beijing: Lifan yuan, 1789; reprinted Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968), p. 124. Batsukhin Bayarsaikhan, Mongol Code (Mongγol čaγaǰin - u bičig) , Monumenta Mongolia IV (Ulaanbaatar: Centre for Mongol Studies, National University of Mongolia, 2004), p. 142.

- Elliott 2001, p. 79.

- Sneath, David (2007). The Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner Asia (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0231511674.

- Chʻing Shih Wen Tʻi. Society for Qing Studies. 1989. p. 70.

- 《清朝通志·氏族略·满洲八旗姓》

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (1 December 2011). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-295-80412-5.

- Patrick Taveirne (January 2004). Han-Mongol Encounters and Missionary Endeavors: A History of Scheut in Ordos (Hetao) 1874-1911. Leuven University Press. pp. 339–. ISBN 978-90-5867-365-7.

- Pamela Kyle Crossley (15 February 2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-520-92884-8.

- Chʻing Shih Wen Tʻi. Society for Qing Studies. 1989. p. 71.

- http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/TUAN-FANG.html

- Crossley, Pamela (June 1983). "restricted access The Tong in Two Worlds: Cultural Identities in Liaodong and Nurgan during the 13th-17th centuries". Ch'ing-shih Wen-t'i. Johns Hopkins University Press. 4 (9): 21–46.

- Pamela Kyle Crossley (15 February 2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-0-520-92884-8. William T. Rowe (15 February 2010). China's Last Empire: The Great Qing. Harvard University Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-674-05455-4. Ruchang Zhou; Ronald R. Gray; Mark S. Ferrara (2009). Between Noble and Humble: Cao Xueqin and the Dream of the Red Chamber. Peter Lang. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-1-4331-0407-7. Pamela Kyle Crossley (15 February 2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-520-92884-8. Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press. pp. 87–. ISBN 978-0-8047-4684-7. David E. Mungello (January 1994). The Forgotten Christians of Hangzhou. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-8248-1540-0. Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0. Chʻing Shih Wen Tʻi. Society for Qing Studies. 1989. pp. 80, 84. Ch'ing-shih Wen-t'i. Ch'ing-shih wen-t'i. 1983. pp. 22, 28, 29. N. Standaert (1 January 2001). Handbook of Christianity in China. Brill. p. 444. ISBN 978-90-04-11431-9.

- jds.cass.cn

- http://www.thepaper.cn/baidu.jsp?contid=1392798

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0804746842.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. p. 128. ISBN 0520928849.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 103–5. ISBN 0520928849.

- https://zhidao.baidu.com/question/84183523.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - http://blog.51cto.com/sky66/1741624. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - http://yukunid.blog.sohu.com/16777875.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - http://blog.sina.cn/dpool/blog/s/blog_6277172c0100hfb3.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 324. ISBN 0804746842.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 331. ISBN 0804746842.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 325. ISBN 0804746842.

- Walthall, Anne, ed. (2008). Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0520254442.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1991). Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World (illustrated, reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0691008779.

- Rawski, Evelyn S. (2001). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 66. ISBN 0520228375.

- 照文武官員負罪逃竄例絞侯SYD 52.1.7 (February 24, 1787).

- GZSL,juan1272, QL 52.1.8 (February 25, 1787).

- Chen, Bijia, et al. “Interethnic Marriage in Northeast China, 1866–1913.” Demographic Research, vol. 38, 2018, p. 953. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26457068?seq=27#metadata_info_tab_contents.

References

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1990), Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691008776

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001), The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China, Stanford University Press, ISBN 9780804746847

- —— (2006), "Concepts of Ethnicity", in Crossley, Pamela Kyle; Siu, Helen F.; Sutton, Donald S. (eds.), Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China, Studies on China, 28, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520230156

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006), China: A New History (2nd enlarged ed.), Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01828-1

- Naquin, Susan (1987), Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-04602-1

- Rawski, Evelyn S. (1991), "Ch'ing imperial marriage and problems of rulership", in Watson, Rubie Sharon; Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (eds.), Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society, University of California Press, pp. 170–203, ISBN 978-0-520-07124-7

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000), Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928, University of Washington Press, ISBN 0-295-98040-0

- Ross, John (1891), The Manchus, Or The Reigning Dynasty of China: Their Rise and Progress, E. Stock

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1988), Ts'ao Yin and the K'ang-hsi Emperor: Bondservant and Master, Yale Historical Publications: Miscellany, 85, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-04277-1

- —— (1990), The Search for Modern China, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-30780-8

- Wakeman, Frederic (1977), The Fall of Imperial China, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-02-933680-5

- —— (1986), The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-04804-0

- Wang, Shuo (2008), "Qing Imperial Women", in Walthall, Anne (ed.), Servants of the Dynasty: Palace Women in World History, University of California Press, pp. 137–158, ISBN 978-0-520-25444-2

![]()

Further reading

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1989), "The Qianlong Retrospect on the Chinese-martial (hanjun) Banners", Late Imperial China, 10 (2): 63–107, doi:10.1353/late.1989.0004

- —— (1999), A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-92884-9

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2010), Kagan, Kimberly (ed.), The Imperial Moment, Paul Bushkovitch, Nicholas Canny, Pamela Kyle Crossley, Arthur Eckstein, Frank Ninkovich, Loren J. Samons, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674054097

- Enatsu, Yoshiki (2004), Banner Legacy: The Rise of the Fengtian Local Elite at the End of the Qing, University of Michigan, ISBN 978-0-89264-165-9

- Im, Kaye Soon. "The Development of the Eight Banner System and its Social Structure," Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities (1991), Issue 69, pp 59–93

- Lococo, Paul (2012), "The Qing Empire", in Graff, David A.; Higham, Robin (eds.), A Military History of China (2nd ed.), University Press of Kentucky, pp. 115–133, ISBN 978-0-8131-4067-4

- Rawski, Evelyn S. (1998), The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-92679-X