Ming tombs

The Ming tombs are a collection of mausoleums built by the emperors of the Ming dynasty of China. The first Ming emperor's tomb is located near his capital Nanjing. However, the majority of the Ming tombs are located in a cluster near Beijing and collectively known as the Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty (Chinese: 明十三陵; pinyin: Míng Shísān Líng; lit.: 'Ming Thirteen Mausoleums'). They are within the suburban Changping District of Beijing Municipality, 42 kilometres (26 mi) north-northwest of Beijing city center. The site, on the southern slope of Tianshou Mountain (originally Huangtu Mountain), was chosen based on the principles of feng shui by the third Ming emperor, the Yongle Emperor. After the construction of the Imperial Palace (Forbidden City) in 1420, the Yongle Emperor selected his burial site and created his own mausoleum. The subsequent emperors placed their tombs in the same valley.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | China |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 1004 |

| Inscription | 2000 (24th session) |

| Extensions | 2003; 2004 |

| Website | http://www.mingtombs.com/ |

| Coordinates | 40°15′12″N 116°13′3″E |

From the Yongle Emperor onwards, 13 Ming dynasty emperors were buried in the same area. The Xiaoling tomb of the first Ming emperor, the Hongwu Emperor, is located near his capital Nanjing; the second emperor, the Jianwen Emperor, was overthrown by the Yongle Emperor and disappeared, without a known tomb. The "temporary" emperor, the Jingtai Emperor, was also not buried here, as the Tianshun Emperor had denied him an imperial burial; instead, the Jingtai Emperor was buried west of Beijing.[1] The last Ming emperor buried at the location was the Chongzhen Emperor, who committed suicide by hanging (on 25 April 1644). He was buried in his concubine Consort Tian's tomb, which was later declared as an imperial mausoleum Si Ling by the emperor of the short-lived Shun dynasty, Li Zicheng, with a much smaller scale compared to the other imperial mausoleums built for Ming emperors.

During the Ming dynasty the tombs were off limits to commoners, but in 1644 Li Zicheng's army ransacked and set many of the tombs on fire before advancing and capturing Beijing in April of that year.

In 1725, the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing dynasty bestowed the hereditary title of Marquis on a descendant of the Ming dynasty imperial family, Zhu Zhiliang, who received a salary from the Qing government and whose duty was to perform rituals at the Ming tombs, and was also inducted the Han Plain White Banner in the Eight Banners. Later the Qianlong Emperor bestowed the title Marquis of Extended Grace posthumously on Zhu Zhuliang in 1750, and the title passed on through twelve generations of Ming descendants until the end of the Qing dynasty.

Presently, the Ming Tombs are designated as one of the components of the World Heritage Site, the Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, which also includes a number of other locations near Beijing and in Nanjing, Hebei, Hubei, Liaoning province.

Layout

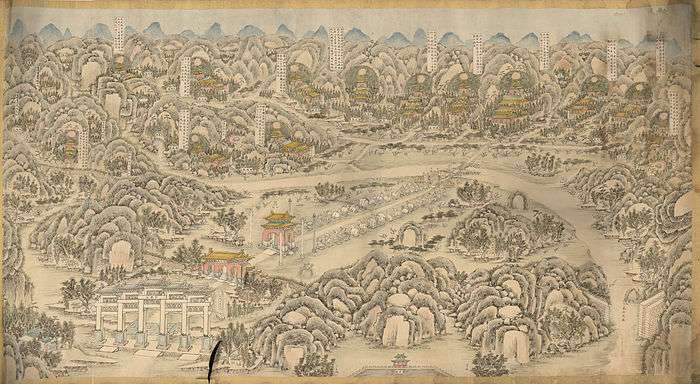

The siting of the Ming dynasty imperial tombs was carefully chosen according to Feng Shui (geomancy) principles. According to these, bad spirits and evil winds descending from the North must be deflected; therefore, an arc-shaped valley area at the foot of the Jundu Mountains, north of Beijing, was selected. This 40 square kilometer area—enclosed by the mountains in a pristine, quiet valley full of dark earth, tranquil water and other necessities as per Feng Shui—would become the necropolis of the Ming dynasty.

A 7-kilometer (4 mi) road named the "Spirit Way" (pinyin: Shéndào) leads into the complex, lined with statues of guardian animals and officials, with a front gate consisting of a three-arches, painted red, and called the "Great Red Gate". The Spirit Way, or Sacred Way, starts with a huge stone memorial archway lying at the front of the area. Constructed in 1540, during the Ming dynasty, this archway is one of the biggest stone archways in China today.

Further in, the Shengong Shengde Stele Pavilion can be seen. Inside it, there is a 50-ton stone statue of Bixi carrying a memorial tablet. Four white marble Huabiao (pillars of glory) are positioned at each corner of the stele pavilion. At the top of each pillar is a mythical beast. Then come two pillars on each side of the road, whose surfaces are carved with the cloud design, and tops are shaped like a rounded cylinder. They are of a traditional design and were originally beacons to guide the soul of the deceased, The road leads to 18 pairs of stone statues of mythical animals, which are all sculpted from whole stones and larger than life size, leading to a three-arched gate known as the Dragon and Phoenix Gate.

At present, only three tombs are open to the public. There have been no excavations since 1989, but plans for new archeological research and further opening of tombs have circulated. They can be seen on Google earth: Chang Ling, the largest (40°18′5.16″N 116°14′35.45″E); Ding Ling, whose underground palace has been excavated (40°17′42.43″N 116°12′58.53″E); and Zhao Ling.

The Ming Tombs were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in August 2003. They were listed along with other tombs under the "Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties" designation.

.

List of the Imperial Tombs

The imperial tombs are in chronological order and list the individuals buried:

The Ming emperors not buried in one of the Thirteen Tombs are: Hongwu Emperor, Kang Emperor, Jianwen Emperor, Jingtai Emperor, and Xian Emperor.

Excavation of Dingling tomb

Dingling (Chinese: 定陵; pinyin: Dìng Lìng; lit.: 'Tomb of Stability'), one of the tombs at the Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty site, is the tomb of the Wanli Emperor, his empress consort and the mother of the Taichang Emperor. It is the only Ming tomb to have been excavated. It also remains the only intact imperial tomb, of any era, to have been excavated since the founding of the People's Republic of China, a situation that is almost a direct result of the fate that befell Dingling and its contents after the excavation.

The excavation of Dingling began in 1956, after a group of prominent scholars led by Guo Moruo and Wu Han began advocating the excavation of Changling, the tomb of the Yongle Emperor, the largest and oldest of the Ming tombs near Beijing. Despite winning approval from premier Zhou Enlai, this plan was vetoed by archaeologists because of the importance and public profile of Changling. Instead, Dingling, the third largest of the Ming Tombs, was selected as a trial site in preparation for the excavation of Changling. Excavation completed in 1957 and a museum was established in 1959.

The excavation revealed an intact tomb, with thousands of items of silk, textiles, wood, and porcelain, and the skeletons of the Wanli Emperor and his two empresses. However, there was neither the technology nor the resources to adequately preserve the excavated artifacts. After several disastrous experiments, the large amount of silk and other textiles were simply piled into a storage room that was draughty and wet from water leaks. As a result, most of the surviving artifacts today have severely deteriorated, and many replicas are instead displayed in the museum. Furthermore, the political impetus behind the excavation created pressure to quickly complete the excavation. The haste meant that documentation of the excavation was poor.

A more severe problem soon befell the project, when a series of political mass movements swept the country. This escalated into the Cultural Revolution in 1966. For the next ten years, all archaeological work was stopped. Wu Han, one of the key advocates of the project, became the first major target of the Cultural Revolution, and was denounced, and died in jail in 1969. Fervent Red Guards stormed the Dingling museum and dragged the remains of the Wanli Emperor and empresses to the front of the tomb, where they were posthumously "denounced" and burned. Many other artifacts were also destroyed.[2]

It was not until 1979, after the death of Mao Zedong and the end of the Cultural Revolution, that archaeological work recommenced in earnest and an excavation report was finally prepared by those archaeologists who had survived the turmoil.

The lessons learned from the Dingling excavation has led to a new policy of the People's Republic of China government not to excavate any historical site except for rescue purposes. In particular, no proposal to open an imperial tomb has been approved since Dingling, even when the entrance has been accidentally revealed, as was the case of the Qianling Mausoleum. The original plan, to use Dingling as a trial site for the excavation of Changling, was abandoned.

Images

- An entrance to a Ming tomb

Ling'en Hall of Changling tomb

Ling'en Hall of Changling tomb Shengong Shengde Stele Pavilion at the beginning of the sacred walk leading to the tombs

Shengong Shengde Stele Pavilion at the beginning of the sacred walk leading to the tombs A statue inside the Ming Dynasty Tombs

A statue inside the Ming Dynasty Tombs- A statue inside the Ming Dynasty Tombs

Ling'en Gate of Changling tomb

Ling'en Gate of Changling tomb A silk burning stove at the Changling tomb

A silk burning stove at the Changling tomb Minglou Tower of Changling tomb

Minglou Tower of Changling tomb

See also

- Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum in Nanjing

- Ming Ancestors Mausoleum in Jiangsu Province

- Eastern Qing tombs near Beijing

- Western Qing tombs near Beijing

- The three imperial tombs north of the great wall

- Fuling Tomb east of Shenyang in Liaoning

- Zhao Mausoleum north of Shenyang in Liaoning

- Yongling Tombs east of Fushun in Liaoning

References

- Eric N. Danielson, "". CHINA HERITAGE QUARTERLY, No. 16, December 2008.

- "China's reluctant Emperor", The New York Times, Sheila Melvin, Sept. 7, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty. |

- Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties on the UNESCO World Heritage List