Kangxi Dictionary

The Kangxi Dictionary (Chinese: 康熙字典; pinyin: Kāngxī Zìdiǎn) was the standard Chinese dictionary during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Kangxi Emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty ordered its compilation in 1710. It used the earlier Zihui system of 214 radicals, today known as 214 Kangxi radicals, and was published in 1716. The dictionary is named after the Emperor's era name.

| Kangxi Dictionary | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

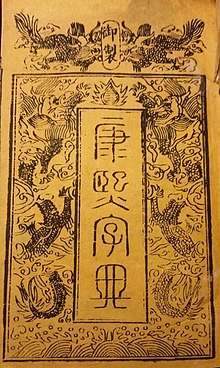

Kangxi Dictionary, 3rd ed. (1827) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 康熙字典 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Khang Hi tự điển | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 康熙字典 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 강희자전 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 康熙字典 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 康熙字典 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | こうきじてん | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

The dictionary contains more than 47,000 characters, though some 40% of them are graphic variants. In addition, there are rare or archaic characters, some of which are attested only once. Fewer than a quarter of the characters it contains are now in common use.[1]

Compilation

The original Kangxi Zidian editors included Zhang Yushu (張玉書, 1642-1711), Chen Tingjing (陳廷敬, 1639-1712), and a staff of thirty. They based it partly on two Ming Dynasty dictionaries: the 1615 Zihui (字彙 "Character Collection") by Mei Yingzuo (梅膺祚), and the 1627 Zhengzitong (正字通 "Correct Character Mastery") by Zhang Zilie (張自烈).

Since the imperial edict required that the Kangxi Dictionary be compiled within five years, a number of errors were inevitable. Although the emperor's preface to the dictionary said, "each and every definition is given in detail and every single pronunciation is provided",[2] Victor H. Mair describes the first edition as “actually quite sloppy and full of mistakes”.[3] The scholar-official Wang Xihou (1713-1777) criticized the Kangxi Zidian in the preface of his dictionary Ziguan (字貫, String of Characters). When the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1725-1796), Kangxi's grandson, was informed of this insult in 1777, Wang's entire family was sentenced to death by the nine familial exterminations, the most extreme form of capital punishment in imperial China.[4] The Daoguang Emperor appointed Wang Yinzhi (1766-1834) and a review board to compile an officially sanctioned supplement to the Kangxi Zidian, and their 1831 Zidian kaozheng (字典考證 "Character Dictionary Textual Research") corrected 2,588 mistakes, mostly in quotations and citations.[5]

The supplemented dictionary contains 47,035 character entries, plus 1,995 graphic variants, giving a total of 49,030 different characters. They are grouped under the 214 radicals and arranged by the number of additional strokes in the character. Although these 214 radicals were first used in the Zihui, due to the popularity of the Kangxi Dictionary they are known as Kangxi radicals and remain in modern usage as a method to categorize traditional Chinese characters.

The character entries give variants (if any), pronunciations in traditional fanqie spelling and in modern reading of a homophone, different meanings, and quotations from Chinese books and lexicons. The dictionary also contains rime tables with characters ordered under syllable rime classes, tones, and initial syllable onsets.

Even the Kangxi Dictionary title is lexicographically significant. After examining his dictionary, the emperor described it as a "canon of characters" (zidian 字典), which became the standard Chinese word for "dictionary", and used in the title of practically every dictionary published since the Kangxi.[6]

The Kangxi Dictionary is available in many forms, from old Qing Dynasty editions in block printing, to reprints in traditional Chinese bookbinding, to modern revised editions with essays in Western-style hardcover, to the digitized Internet version.

In a groundbreaking lexicographical project based on the Kangxi dictionary, Walter Henry Medhurst, an early translator of the Bible into Chinese, compiled a bilingual dictionary (1842) "containing all the words in the Chinese imperial dictionary".

The Kangxi Dictionary is one of the Chinese dictionaries used by the Ideographic Rapporteur Group for the Unicode standard.

Structure

- Preface by Kangxi Emperor: pp. 1–6 (御製序)

- Notes: pp. 7–12 (凡例)

- Phonology: pp. 13–40 (等韻)

- Table of contents: pp. 41–49 (總目)

- Index of characters: pp. 50–71 (檢字)

- The dictionary proper: pp. 75–1631

- Main text: pp. 75–1538

- Addendum contents: pp. 1539–1544 (補遺)

- Addendum text: pp. 1545–1576

- Appendix contents (No–source–characters): pp. 1577–1583 (備考)

- Appendix text: pp. 1585–1631

- Postscript: pp. 1633–1635 (後記)

- Textual research: pp. 1637–1683 (考證)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kangxi Dictionary. |

- Dai Kan-Wa jiten

- Han-Han Dae Sajeon

- Hanyu Da Zidian

- List of Kangxi radicals

- Peiwen Yunfu

- Zhonghua Da Zidian

References

- Creamer, Thomas B. I. (1992), "Lexicography and the history of the Chinese language", in History, Languages, and Lexicographers, (Lexicographica, Series maior 41), ed. by Ladislav Zgusta, Niemeyer, 105-135.

- Mair, Victor H. (1998), "Tzu-shu 字書 or tzu-tien 字典 (dictionaries)," in The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature (Volume 2), ed. by William H. Nienhauser, Jr., et. al, SMC Publishing, 165-172.

- Medhurst, Walter Henry (1842), Chinese and English dictionary, containing all the words in the Chinese imperial dictionary; arranged according to the radicals, 2 vols., Parapattan.

- Teng, Ssu-yü and Biggerstaff, Knight. 1971. An Annotated Bibliography of Selected Chinese Reference Works, 3rd ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-03851-7

Notes

- Endymion Wilkinson. Chinese History: A New Manual. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Asia Center, Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, 2012. ISBN 9780674067158), pp. 80-81.

- Tr. Creamer 1992: 117.

- Mair 1998: 169.

- Creamer 1992: 117.

- Teng and Biggerstaff 1971:130

- Creamer 1992: 117.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kangxi Dictionary. |

- Kangxi Zidian (Tongwen Shuju edition), with dictionary lookup – Chinese Text Project

- Kangxi (Emperor of China) (1842). Chinese and English dictionary: containing all the words in the Chinese imperial dictionary; arranged according to the radicals, Volume 1. Printed at Parapattan. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- 康熙字典網上版 Kangxi Dictionary Online Version

- Kangxi zidian 康熙字典 (in English), brief history of the dictionary, on Chinaknowledge.de

- 汉典 The Chinese Language Dictionary Homepage (in Chinese only)

- Making Friends with the Kangxi zidian 康熙字典 at the Wayback Machine (archived February 7, 2012), Occasional paper with translation of Kangxi Emperor's preface 御製康熙字典序

- 訂正康熙字典 EPUB版 Revised Kangxi Zidian, EPUB Version