Khitan people

The Khitan people (Khitan small script: ![]()

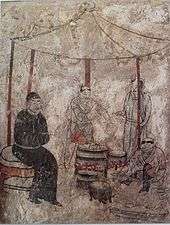

Depiction of Khitans by Hugui (胡瓌, 9th/10th century), hunting with eagles | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| East and Central Asia | |

| Languages | |

| Khitan | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Buddhism Minorities: Shamanism, Tengriism, Christianity, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mongols, Daur |

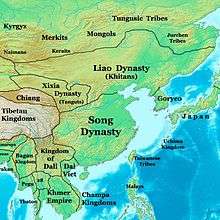

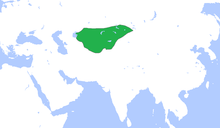

As a people descended from the proto-Mongols,[1] they spoke the Khitan language, which appears to be related to the Mongolic languages. During the Liao dynasty, they dominated a vast area of Siberia and Northern China. After the fall of the Liao dynasty in 1125 following the Jurchen invasion, many Khitans followed Yelü Dashi's group westward to establish the Qara Khitai or Western Liao dynasty, in Central Asia, which lasted several decades before falling to the Mongol Empire in 1218. Other regimes founded by the Khitans included the Northern Liao, Eastern Liao and Later Liao in China, as well as the Qutlugh-Khanid dynasty in Persia.

Etymology

There is no consensus on the etymology of the name of Khitan. There are basically three speculations. Feng Jiasheng argues that it comes from the Yuwen chieftains' names.[2] Zhao Zhenji thinks that the term originated from Xianbei and means "a place where Xianbei had resided". Japanese scholar Otagi Matsuo believes that Khitan's original name was "Xidan", which means "the people who are similar to the Xi people" or "the people who inhabit among the Xi people".[3]

China

Due to the dominance of the Khitans during the Liao dynasty in northern China and later the Qara Khitai in Central Asia where they were seen as Chinese, the term "Khitai" came to mean "China" to people near them in Central Asia and northwestern China. The name was then introduced to medieval Europe via Islamic and Russian sources, and became "Cathay". In the modern era, words related to Khitay are still used by Turkic peoples, such as the Uyghurs in China's Xinjiang region and the Kazakhs of Kazakhstan and areas adjoining it, as a name for China. The Han Chinese consider the ethnonym derived from Khitay (as applied to them by the Uyghurs) to be pejorative and the Chinese government has tried to ban its use.[4]

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Manchuria |

|

|

Ancient period

|

|

Modern period |

Origin myth

According to an official history compiled in the 14th century, a "sacred man" (shen-ren) on a white horse had eight sons with a "heavenly woman" (tiannü) who rode in a cart pulled by a grey ox. The man came from the T'u River (Lao Ha river in modern-day Jilin, Manchuria) and the woman from the Huang River (modern day Xar Moron river in Inner Mongolia). The pair met where the two rivers join, and the eight sons born of their union became eight tribes.[5]

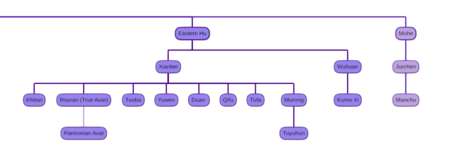

Pre-dynastic

The earliest written reference to the Khitan is from an official history of the Xianbei Northern Wei Dynasty dating to the period of the Six Dynasties. Most scholars believe the Khitan tribe splintered from the Xianbei, and some scholars believe they may have been a mixed group who also included former members of the Xiongnu tribal confederation.[6][7] The Khitan shaved their heads, leaving hair on their temples which grew down to the chest, in a similar fashion as the related Kumo Xi, Shiwei and Xianbei whom they are believed to be descended from.[8]

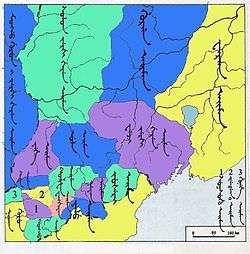

During their early history the Khitan were composed of eight tribes. Their territory was between the present-day Xar Moron River and Chaoyang, Liaoning.[9] The Khitan's territory bordered Goguryeo, China and the lands of the Eastern Turks.[10]

Between the 6th and 9th centuries, they were successively dominated by the Eastern Turkic Khaganate, the Uyghur Khaganate, and the Chinese Tang dynasty.[11] The Khitan were less politically united than the Turkic tribes, but often found themselves involved in the power games between the Turks and the Chinese dynasties of Sui and Tang. It is estimated the Khitan had only around 43,000 soldiers—a fraction of the Turkic Khaganates.[10] In 605, the Khitan raided China, but the Emperor Yangdi of the Sui dynasty was able to convince the Turks to send 20,000 horsemen to aid China against the Khitan.[12] In 628, under the leadership of tribal chief Dahe Moui, the Khitan submitted to the Tang dynasty, as they had earlier submitted to the Eastern Turks. The Khagan of the Eastern Turks, Jiali Khan, offered to exchange the Chinese rebel Liang Shi Du for the Khitan, but Emperor Taizong would not agree to the exchange.[9]

During the reign of Empress Wu, nearly one century later, the Second Turkic Khaganate raided along the Northern China's borderlands. The Tang Empress, in what scholars consider a major strategic error, formed an ill-fated alliance with the Turkic leader Qapaghan Qaghan to punish the Khitan for raiding Hebei province. Khitan territory was much closer to Northern China than Turkic lands, and the Turks used it to launch their own raids into Hebei.[13]

Like the Tuyuhun and Tangut, the Khitan remained an intermediate power along the borderlands through the 7th and 8th centuries.[14] The Khitans rose to prominence in a power vacuum that developed in the wake of the Kyrgyz takeover of the Uyghur Khaganate, and the collapse of the Tang Dynasty.[15]

Liao dynasty

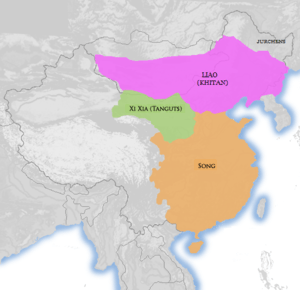

Abaoji, who had been successful in uniting the Khitan tribes, founded the Liao dynasty in 907. The Liao territory included Manchuria, Mongolia and parts of China. Although transition to an imperial social and political organization was a significant change for the Khitans, the Khitan language, origin myth, shamanic religion and nomadic lifestyle endured.[11]

China was in chaos after the fall of the Tang dynasty in 907. Known as the Wudai Shiguo period, Five Dynasties ruled northern China in rapid succession with only nominal support from the Ten Kingdoms of southern China.[16] The Tang dynasty had been supported by Shatuo Turks until Zhu Wen murdered the last Tang emperor and founded the Later Liang dynasty. The Shatuo Turks, who had been allied with the Khitans since 905, defeated the Later Liang and founded the Later Tang dynasty in 923, but by 926 the former allies had grown apart.[17] In 934 Yelü Bei, Abaoji's son, wrote to his brother Emperor Taizong of Liao from the Later Tang court: "Li Cong Ke has slain his liege-lord, why not attack him?"[18] In 936, the Khitans supported Shi Jing Tang's rebellion against the Later Tang Emperor Li Cong Ke. Shi Jing Tang became emperor of the Later Jin dynasty and, in exchange for their support, the Khitans gained sixteen new prefectures.[19][17]

The Later Jin dynasty remained a vassal of the Khitans until the death of Shi Jing Tang in 942, but when the new emperor ascended, he indicated that he would not honor his predecessor's arrangement. The Khitans launched a military invasion against the Later Jin in 944. In January 947, the Emperor of the Later Jin dynasty surrendered to the Khitans.[20] The Khitan emperor left the conquered city of Kaifeng and unexpectedly died from an illness while travelling in May 947.[21]

Relations between Goryeo and the Khitans were hostile after the Khitans destroyed Balhae. Goryeo would not recognize the Liao dynasty and supported the fledgling Song dynasty, which had formed south of the Khitans' territory. Though the Khitans would have preferred to attack China, they invaded Goryeo in 993. Khitan forces failed to advance beyond the Chongchon River and were persuaded to withdraw, though Khitan dissatisfaction with Goryeo's conquest of the Jurchen prompted a second invasion in 1010. This time the Khitans, led by their emperor, sacked the capital city Kaesong. A third and final invasion in 1018 was repelled by Goryeo's forces, bringing an end to 30 years of war between the rivals.[22]

The Liao dynasty proved to be a significant power north of the Chinese plain, continuously moving south and west, gaining control over former Chinese and Turk-Uyghur territories. In 1005 Chanyuan Treaty was signed, and peace remained between the Liao dynasty and the Song dynasty for the next 120 years. During the reign of the Emperor Daozong of Liao, corruption was a major problem and prompted dissatisfaction among many people, including the Jurchens. The Liao dynasty eventually fell to the Jin dynasty of the Jurchen in 1125, who defeated and absorbed the Khitans to their military benefit. The Khitans considered the Khamag Mongols as their last hope when the Liao dynasty was invaded by the Jin, Song dynasty and Western Xia Empires.

To defend against the Jurchens and Khitans, a Long Wall was built by Goryeo in 1033–1034, along with many border forts.[23]

Following the fall of the Liao dynasty, a number of the Khitan nobility escaped the area westwards towards Western Regions, establishing the short-lived Qara Khitai or Western Liao dynasty. After its fall, a small part under Buraq Hajib established a local dynasty in the southern Persian province of Kirman. These Khitans were absorbed by the local Turkic and Iranian populations, Islamized and left no influence behind them. As the Khitan language is still almost completely illegible, it is difficult to create a detailed history of their movements.

During the 13th century, the Mongol invasions and conquests had a large impact on shifting ethnic identities in the region. Most people of the Eurasian Steppe did not retain their pre-Mongol identities after the conquests. The Khitans were scattered across Eurasia and assimilated into the Mongol Empire in the early 13th century.[24]

Fleeing from the Mongols, in 1216 the Khitans invaded Goryeo and defeated the Goryeo armies several times, even reaching the gates of the capital and raiding deep into the south, but were defeated by Goryeo General Kim Chwi-ryeo who pushed them back north to Pyongan,[25][26] where the remaining Khitans were finished off by allied Mongol-Goryeo forces in 1219.[27][28]

Language and writing systems

The Khitan language is now extinct. Some scholars believe that Khitan is Proto-Mongolic, while others have suggested that it is a Para-Mongolic language.[29] Khitan has loanwords borrowed from the Turkic Uyghur language[30] and Koreanic languages.[31]

There were two writing systems for the Khitan language, known as the large script and the small script. These were functionally independent and appear to have been used simultaneously in the Liao dynasty. They were in use for some time after the fall of that dynasty. Examples of the scripts appeared most often on epitaphs and monuments, although other fragments sometimes surface. The Khitan scripts have not been fully deciphered and more research and discoveries will be necessary for a proficient understanding of them.[32][33]

Economy

As nomadic Khitans originally engaged in stockbreeding, fishing, and hunting. Looting Chinese villages and towns as well as neighboring tribes was also a helpful source of slaves, Chinese handcraft, and food, especially in times of famine. Under the influence of China, and following the administrative need for a sedentary administration, the Khitans began to engage in farming, crop cultivation and the building of cities. Different from the Chinese and Balhae farmers, who cultivated wheat and sorghum millet, the Khitan farmers cultivated panicled millet. The ruling class of the Liao dynasty still undertook hunting campaigns in late summer in the tradition of their ancestors. After the fall of the Liao dynasty, the Khitans returned to a more nomadic life.

Religion

The Khitans practiced shamanism in which animals played an important role. Hunters would offer a sacrifice to the spirit of the animal they were hunting and wore a pelt from the same animal during the hunt. There were festivals to mark the catching of the first fish and wild goose, and annual sacrifices of animals to the sky, earth, ancestors, mountains, rivers, and others. Every male member of the Khitan would sacrifice a white horse, white sheep, and white goose during the Winter solstice.[34]

When a Khitan nobleman died, burnt offerings were sacrificed at the full and new moons. The body was exposed for three years in the mountains, after which the bones would be cremated. The Khitan believed that the souls of the dead rested at a place called the Black Mountain, near Rehe Province.[35]

Khitan tents always faced east, and they revered the sun, but the moon did not have a large role in their religion.[36] They also practiced a form of divination where they went to war if the shoulder blade of a white sheep cracked while being heated (scapulimancy).[34]

Women

Khitan women hunted, rode horses and practiced archery. They did not practice foot binding, which started becoming popular among the Han during the Song dynasty. The Khitan practiced polygamy and generally preferred marriage within the tribe, but it was not unknown for an Emperor to take wives from other groups, such as Han, Korean,[37] and Turkic[38]

Genetics

The Khitan have been associated with the expansion of the paternal C3 (xC3c) Y haplogroup in Inner Mongolia.[39]

Gallery

Horsemen

Horsemen Horsemen at rest

Horsemen at rest Hunters

Hunters

Khitan holding a mace

Khitan holding a mace Khitan guards

Khitan guards Khitans

Khitans Cooks

Cooks Boys and girls

Boys and girls_from_Tomb_in_Aohan%2C_Liao_Dynasty.jpg) Hairstyle

Hairstyle.jpg) Women

Women.jpg) Women

Women.jpg) Woman

Woman

See also

- History of the Khitans

- List of Khitan rulers

- Yelü

- Liao dynasty

- Northern Liao

- Qara Khitai (also called "Western Liao")

- Eastern Liao

- Later Liao

- Qutlugh-Khanids

References

Citations

- "China's Liao Dynasty". Asia Society.

- Xu 2005, p. 7.

- Xu 2005, pp. 8-9.

- Starr 2015, p. 43.

- Grayson 2012, p. 124.

- San 2014, p. 233.

- Kim 2013, pp. 61-62.

- Denis C. Twitchett; Herbert Franke; John King Fairbank (1994). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Hung 2013, p. 144.

- Skaff 2012, p. 38.

- Biran 2017, p. 153.

- Cohen 2001, p. 64.

- Skaff 2012, p. 48.

- Skaff 2012, p. 39.

- Kim 2013, p. 62.

- Kim 2013, p. 63.

- Mote 2003, pp. 12-13.

- Dudbridge 2013, p. 24.

- Hung 2013, pp. 22.

- Hung 2013, pp. 23-27.

- Dudbridge 2013, pp. 29-30.

- Kim 2005, pp. 57-58.

- Seth 2010, p. 86.

- Biran 2017, pp. 152-181.

- "Kim Chwi-ryeo". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Goryeosa: Volume 103. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Ebrey & Walthall 2013, p. 177.

- Lee 1984, p. 148.

- Janhunen 2014, p. 4.

- Mote 2003, p. 34.

- Vovin, Alexander (June 2017). "Koreanic loanwords in Khitan and their importance in the decipherment of the latter". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 70 (2): 207–215. doi:10.1556/062.2017.70.2.4.

- Daniels & Bright 1996, pp. 230-234.

- Kara 1987, pp. 19-23.

- Baldick 2012, p. 32.

- Baldick 2012, pp. 32-33.

- Baldick 2012, p. 34.

- McMahon 2013, p. 272.

- Denis C. Twitchett, Herbert Franke, John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6, Alien Regimes and... p. 46.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Balaresque, Patricia; Poulet, Nicolas; Cussat-Blanc, Sylvain; Gerard, Patrice; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Heyer, Evelyne; Jobling, Mark A (14 January 2015). "Y-chromosome descent clusters and male differential reproductive success: young lineage expansions dominate Asian pastoral nomadic populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 23 (10): 1413–1422. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2014.285. PMC 4430317. PMID 25585703.

Sources

- Works cited

- Anderson, E. N. (2014). Food and Environment in Early and Medieval China. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9009-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baldick, Julian (2012). Animal and Shaman: Ancient Religions of Central Asia. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7165-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biran, Michal (2017). "7. The Mongols and Nomadic Identity: The Case of the Kitans in China". Nomads as Agents of Cultural ChangeThe Mongols and Their Eurasian Predecessors. Berlin, Boston: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-4789-0. Retrieved 2018-02-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, Warren I. (2001). East Asia at the Center: Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-50251-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (1996). The World's Writing Systems. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 230–234.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dudbridge, Glen (2013). A Portrait of Five Dynasties China: From the Memoirs of Wang Renyu (880-956). OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-164967-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ebrey, Patricia; Walthall, Anne (2013). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-133-60651-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kara, György (1987). "On the Khitan Writing Systems". Mongolian Studies: 19–23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hung, Hing Ming (2013). Li Shi Min, Founding the Tang Dynasty: The Strategies that Made China the Greatest Empire in Asia. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-980-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grayson, James H. (2012). Myths and Legends from Korea: An Annotated Compendium of Ancient and Modern Materials. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-60289-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Janhunen, Juha (2014). Mongolian. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. p. 4. ISBN 9789027238252.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06722-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kim, Djun Kil (2005). The History of Korea. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-03853-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 067461576X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Middleton, John (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45157-0.

- McMahon, Keith (2013). Women Shall Not Rule: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Han to Liao. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-2290-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mote, Frederick W. (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- San, Tan Koon (2014). Dynastic China: An Elementary History. The Other Press. ISBN 978-983-9541-88-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seth, Michael J. (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-6717-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012). Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires). Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Starr, S. Frederick (2015). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45137-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Xu, Elina-Qian (2005). "Historical development of the pre-dynastic Khitan". Retrieved 2018-02-13. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Other webpages

- Khitans

- Khitans on scholar.google.com

- Exhibition of Khitan artifacts

- Khitan gers

.png)