Former eastern territories of Germany

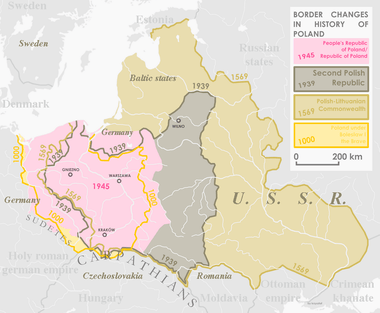

The former eastern territories of Germany (German: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) are those provinces or regions east of the current eastern border of Germany (the Oder–Neisse line) which were lost by Germany after World War I and then World War II; having been parts of the German Empire from 1871, and previously, of Prussia and Austria. They include provinces that historically had been considered 'German', and others that only became 'German' in 1871.

| Territorial evolution of Germany in the 20th century |

|---|

|

Pre-World War II

|

|

Post-World War II

|

|

Adjacent countries |

| Territorial evolution of Poland in the 20th century |

|---|

|

Post World War I

|

|

|

Post World War II

|

|

Areas

|

|

Demarcation lines

|

|

Adjacent countries |

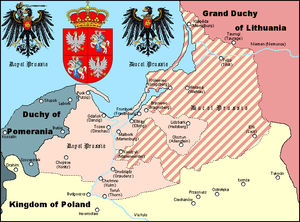

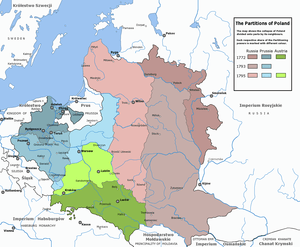

The territories lost by Germany following World War I included areas with predominantly ethnically Polish population, especially the Province of Posen (Greater Poland and Kuyavia), most of the province of West Prussia (see the Polish Corridor), and East Upper Silesia reintegrated with Poland,[1] following the country's independence, as well as the Lithuanian-populated Klaipėda Region, which became part of Lithuania. Further territories lost after World War II include East Prussia, Farther Pomerania, Neumark, West Upper Silesia, and almost all of Lower Silesia (except for a small area east of and around Hoyerswerda). The territories lost in both World Wars account for 33% of the pre-1914 German Empire, while land ceded by Germany after World War II constituted roughly 25% of its pre-war Weimar territory.[2] In present-day Germany, the term 'Former eastern territories' usually refers only to those territories lost in World War II.[3] Territories acquired by Poland after World War II were called there the Recovered Territories.[4] These territories had been ruled as part of Poland by the Piast dynasty in or since the High Middle Ages, with the exception of Prussia which was inhabited by Old Prussians and came under Polish suzerainty in the Late Middle Ages, and had become predominantly German over the centuries. Part of historic Prussia became part of the Soviet Union as the Kaliningrad Oblast, now within Russia. The German population of the territories that had not fled in 1945 was expelled, forming the majority of the Germans expelled from Eastern Europe.

The post-war border between Germany and Poland along the Oder–Neisse line was formally recognized by East Germany in 1950, by the Treaty of Zgorzelec, under pressure from Stalin. In 1952, recognition of the Oder–Neisse line as a permanent boundary was one of Stalin's conditions for the Soviet Union to agree to a reunification of Germany (see Stalin Note). The offer was rejected by West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. The then official West German government position on the status of former eastern territories of Germany east of the Oder and Neisse rivers was that the areas were "temporarily under Polish [or Soviet] administration." In official maps produced in West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s, the boundaries of Germany as at 31 December 1937 were stated as 'continuing to be valid in international law'.

In 1970, West Germany recognised the Oder-Neisse line as the de facto western boundary of Poland by the Treaty of Warsaw; and in 1973, the Federal Constitutional Court acknowledged the capability of East Germany to negotiate the Treaty of Zgorzelec as an international agreement binding as a legal definition of its boundaries. In signing the Helsinki Final Act in 1975, both West Germany and East Germany recognised the existing boundaries of post-war Europe, including the Oder-Neisse line, as valid in international law.

In 1990, as part of the reunification of Germany, West Germany accepted clauses in the Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany whereby Germany renounced all claims to territory east of the Oder–Neisse line.[5] Germany's recognition of the Oder–Neisse line as the border was formalised by the re-united Germany in the German–Polish Border Treaty on November 14, 1990; and by the repeal of Article 23 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany under which German states outside the Federal Republic could formerly apply for admission. With this repeal the post-1990 boundaries of Germany are closed to further expansion.

Usage

In the Potsdam Agreement the description of the territories transferred is "The former German territories east of the Oder–Neisse line", and permutations on this description are the most commonly used to describe any former territories of Germany east of the Oder–Neisse line.

The name East Germany, a political term, used to be the common colloquial English name for the German Democratic Republic (GDR), and mirrored the common colloquial English term for the other German state of West Germany. When focusing on the period before World War II, "eastern Germany" is used to describe all the territories east of the Elbe (East Elbia), as reflected in the works of sociologist Max Weber and political theorist Carl Schmitt,[6][7][8][9][10] but because of the border changes in the 20th century, after World War II the term "East Germany" and eastern Germany in English has meant the territory of the German Democratic Republic.

In German there is only one usual term, Ostdeutschland, meaning East Germany or Eastern Germany. The rather ambiguous German term never gained prevailing use for the GDR as did the English term. Since reunification, Ostdeutschland has been commonly used to denote both the historic post-war German Democratic Republic, and its counterpart five successor states in the current reunited Germany. However, because people and institutions in the states traditionally considered as Middle Germany, like the three southern new states Saxony-Anhalt, the Free State of Saxony and the Free State of Thuringia, still use the term Middle Germany when referring to their area and its institutions, the term Ostdeutschland is still ambiguous.[11]

History

Antic, Medieval and early modern era

As various Germanic tribes settled in the region of central Europe, to the east several different West Slavic tribes inhabited most of the area of present-day Poland from the 6th century. Duke Mieszko I of the Polans, from his stronghold in the Gniezno area, united various neighboring tribes in the second half of the 10th century, forming the first Polish state and becoming the first historically recorded Piast duke. His realm bordered German state, and control over the borderlands would shift back and forth between the two polities over the centuries to come.

Mieszko's son and successor, Duke Bolesław I Chrobry, upon the 1018 Peace of Bautzen expanded the southern part of the realm, but lost control over the lands of Western Pomerania on the Baltic coast. After pagan revolts and a Bohemian invasion in the 1030s, Duke Casimir I the Restorer (reigned 1040-1058) again united most of the former Piast realm, including Silesia and Lubusz Land on both sides of the middle Oder River, but without Western Pomerania, which became part of the Polish state again under Bolesław III Wrymouth from 1116 until 1121, when the noble House of Griffins established the Duchy of Pomerania. On Bolesław's death in 1138, Poland for almost 200 years was subjected to fragmentation, being ruled by Bolesław's sons and by their successors, who were often in conflict with each other. Władysław I the Elbow-high, crowned king of Poland in 1320, achieved partial reunification, although the Silesian and Masovian duchies remained independent Piast holdings.

In the course of the 12th to 14th centuries, Germanic, Dutch and Flemish settlers moved into East Central and Eastern Europe in a migration process known as the Ostsiedlung. In Pomerania, Brandenburg, Prussia and Silesia, the former West Slav (Polabian Slavs and Poles) or Balt population became minorities in the course of the following centuries, although substantial numbers of the original inhabitants remained in areas such as Upper Silesia. In Greater Poland and in Eastern Pomerania (Pomerelia), German settlers formed a minority. Some of the territories (such as Pomerelia and Masovia) reunited with Poland during the 15th and 16th centuries. Others became more firmly incorporated into German polities.

In 1815, the Congress of Vienna established The German Confederation (German: Deutscher Bund) as an association of 39 German-speaking states in Central Europe. This established the boundaries of Germany for much of the 19th century; as including Pomerania, East Brandenburg and Silesia, but excluding German-speaking lands in the eastern portion of the Kingdom of Prussia (East Prussia, West Prussia and Posen), as well as the German cantons of Switzerland, and the French region of Alsace..

Pomerania

The Pomeranian parts of the former eastern territories of Germany had been under Polish rule several times from the late 10th century on, when Mieszko I acquired at least significant parts of them. Mieszko's son Bolesław I established a bishopric in the Kołobrzeg area in 1000–1005/07, before the area was lost by Poland again to pagan Slavic tribes. Despite further attempts by Polish dukes to again control the Pomeranian tribes, this was only partly achieved by Bolesław III in several campaigns lasting from 1116 to 1121. Successful Christian missions ensued in 1124 and 1128; however, by the time of Bolesław's death in 1138, most of West Pomerania (the Griffin-ruled areas) was no longer controlled by Poland. The easternmost part of later Western/Farther Pomerania[Note 1] in the 13th century was part of Gdańsk Pomerania and was re-integrated with Poland, and later on, in the 14th and 15th centuries formed a duchy, whose rulers were vassals of the Jagiellonian-ruled Kingdom of Poland, before it was integrated with Western/Farther Pomerania. Over the following centuries the area was largely Germanized, although a small Slavic or Polish minority remained. Indigenous Slavs and Poles faced discrimination from the arriving Germans, who on a local level since the 16th century imposed discriminatory regulations, such as bans on buying goods from Slavs/Poles or prohibiting them from becoming members of craft guilds.[12] The Duchy of Pomerania under the native Griffin dynasty existed for over 500 years, before it was partitioned between Sweden and Brandenburg-Prussia in the 17th century. The Swedish-controlled areas fell to the Kingdom of Prussia in the 18th and 19th century.

At the turn of the 20th century there lived only about 14,200 persons of Polish mother-tongue in the Province of Pomerania (in the east of Farther Pomerania in the vicinity of the border with West Prussia), and 300 persons using the Kashubian language (at the Leba Lake and the Garde Lake), the total population of the province consisting of almost 1.7 million inhabitants.

Gdańsk, Lębork and Bytów

The region of Pomerelia/Gdańsk Pomerania at the eastern end of Pomerania, including Gdańsk (Danzig), was part of Poland since its first ruler Mieszko I. As a result of the fragmentation of Poland, it was ruled in the 12th and 13th centuries by the Samborides, who were (at least initially) more closely tied to the Kingdom of Poland than were the Griffins. After the Treaty of Kępno in 1282, and the death of the last Samboride in 1294, the region was ruled by kings of Poland for a short period, although also claimed by Brandenburg. After the Teutonic takeover in 1308 the region was annexed to the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights. In the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) most of the region became part of Royal Prussia within the Kingdom of Poland, as it remained until being annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in the partitions of 1772 and 1793. A small area in the west of Pomerelia, the Lauenburg and Bütow Land (the region of Lębork and Bytów) was granted to the rulers of Pomerania as a Polish fief, before being reintegrated with Poland in 1637, and later on, again transformed into a Polish fief, which it remained until the First Partition of Poland. After Poland regained independence in 1918, a large part of Pomerelia was reintegrated with Poland as the so-called Polish Corridor, a part formed the Free City of Danzig in customs union with Poland, and small parts remained within Germany. The entire region was reintegrated with Poland in 1945.

Lubusz Land

.jpg)

The medieval Lubusz Land on both sides of the Oder River up to the Spree in the west, including Lubusz (Lebus) itself, also formed part of Mieszko's realm. Poland lost Lubusz when the Silesian duke Bolesław II Rogatka sold it to the Ascanian margraves of Brandenburg in 1249. Brandenburg also acquired the castellany of Santok from Duke Przemysł I of Greater Poland and made it the nucleus of their Neumark ("New March") region. The Bishopric of Lebus remained a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Gniezno until 1424, when it passed under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Magdeburg. The Lubusz Land was part of the Lands of the Bohemian (Czech) Crown from 1373 to 1415. The present-day Polish Lubusz Voivodeship comprises most of the former Brandenburgian Neumark territory east of the Oder.

Parts of Greater Poland and Kuyavia

A portion of the former eastern territory east of the Lubusz Land had previously formed the western parts of the Polish provinces of Pomerelia and Greater Poland (Polonia Maior), being lost to Prussia in the First Partition (the Pomerelian parts) and the Second Partition (the remainder). During Napoleonic times the Greater Poland territories formed part of the Duchy of Warsaw, but after the Congress of Vienna Prussia reclaimed them as part of the Grand Duchy of Posen (Poznań), later Province of Posen. After World War I, those parts of the former Province of Posen and of West Prussia that were not restored as part of the Second Polish Republic were administered as Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen (the German Province of Posen–West Prussia) until 1939.

Silesia

Silesia also formed part of Poland since Mieszko I of Poland and Piast dukes continued to rule Silesia following the 12th-century fragmentation of Poland. The Silesian Piasts retained power in most of the region until the early 16th century, the last (George William, duke of Legnica) dying in 1675. After the Piasts some Lower Silesian duchies were under the rule of Polish Jagiellons (Głogów) and Sobieskis (Oława), Czech Přemyslids and Poděbrads (Münsterberg/Ziębice) and part of Upper Silesia, the Duchy of Opole, found itself back under Polish rule in the mid-17th century, when the Habsburgs pawned the duchy to the Polish Vasas. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Wrocław, established in 1000 as one of Poland's oldest dioceses, remained a suffragan of the Archbishopric of Gniezno until 1821.

The first German colonists arrived in the late 12th century, and large-scale German settlement started in the early 13th century during the reign of Henry I[14] (Duke of Silesia from 1201 to 1238 and of all-Poland from 1232 to 1238). After the era of German colonisation, the Polish language still predominated in Upper Silesia and in parts of Lower and Middle Silesia north of the Odra river. Here the Germans who arrived during the Middle Ages became mostly Polonized; Germans dominated in large cities and Poles mostly in rural areas. The Polish-speaking territories of Lower and Middle Silesia, commonly described until the end of the 19th century as the Polish side, were mostly Germanized in the 18th and 19th centuries, except for some areas along the northeastern frontier.[15][16] The province came under the control of Kingdom of Bohemia in the 14th century and was briefly under Hungarian rule in the 15th century. Silesia passed to the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria in 1526, and Prussia's Frederick the Great conquered most of it in 1742. A part of Upper Silesia became part of Poland after World War I, but the bulk of Silesia formed part of the post-1945 Recovered Territories.

History of Brandenburg and Prussia | ||||

| Northern March 965–983 |

Old Prussians pre-13th century | |||

| Lutician federation 983 – 12th century | ||||

| Margraviate of Brandenburg 1157–1618 (1806) (HRE) (Bohemia 1373–1415) |

Teutonic Order 1224–1525 (Polish fief 1466–1525) | |||

| Duchy of Prussia 1525–1618 (1701) (Polish fief 1525–1657) |

Royal (Polish) Prussia (Poland) 1454/1466 – 1772 | |||

| Brandenburg-Prussia 1618–1701 | ||||

| Kingdom in Prussia 1701–1772 | ||||

| Kingdom of Prussia 1772–1918 | ||||

| Free State of Prussia (Germany) 1918–1947 |

Klaipėda Region (Lithuania) 1920–1939 / 1945–present |

Recovered Territories (Poland) 1918/1945–present | ||

| Brandenburg (Germany) 1947–1952 / 1990–present |

Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia) 1945–present | |||

Warmia and Masuria

The northern territories of Warmia and Masuria form the areas of the former eastern territories of Germany that had been Polish fiefs. Originally inhabited by pagan Old Prussians, these regions became were conquered and incorporated into the state of the Teutonic Knights in the 13th and 14th centuries. By the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), Warmia was awarded to the Polish Crown as part of Royal Prussia, though with considerable autonomy, while Masuria became part of a Polish fief, first as part of the Teutonic state, and from 1525 as part of the secular Ducal Prussia. Prussia took direct control of the region in the First Partition of Poland (1772) and in 1773 included the area in the newly formed province of East Prussia. It formed the southern part of the province after World War I, becoming part of Poland after World War II, with northern East Prussia going to the Soviet Union to form the Kaliningrad Oblast.

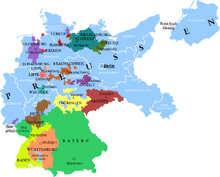

Foundation of German Empire, 1871

At the time of the foundation of the German Empire in 1871, the Kingdom of Prussia was the largest and dominant part of the empire. Prussian territory east of the Oder–Neisse line included West Prussia and Posen (taken by Prussia in the first two Partitions of Poland in the 18th century), also Silesia, East Brandenburg, and Pomerania. Later, these territories would come to be called in Germany "Ostgebiete des deutschen Reiches" (Eastern territories of the German Empire). After 1871, the boundaries of 'Germany' came to be understood as having been extended to include the whole of Prussian territory.

Treaty of Versailles, 1919

The Treaty of Versailles of 1919 that ended World War I restored the independence of Poland, known as the Second Polish Republic, and Germany was compelled to cede territories to it, most of which were taken by Prussia in the three Partitions of Poland, and had been part of the Kingdom of Prussia and later the German Empire for over 100 years. The territories ceded to Poland in 1919 were those with an apparent Polish majority, such as the Province of Posen, the east-southern part of Upper Silesia and the so-called Polish Corridor.

Division of Germany's eastern provinces after 1918

| From province: | Area in 1910 in km2 | Share of territory | Population in 1910 | After WW1 part of: | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Prussia | 25,580 km2[17] | 100% | 1.703.474 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 15,900 km2[17] | 62% [18] | 57%[18] | Pomeranian Voivodeship | [Note 2] |

| to Free City Danzig | 1,966 km2 | 8% | 19% | Free City of Danzig | |

| to East Prussia

(within Weimar Germany) |

2,927 km2 | 11% | 15% | Region of West Prussia | [Note 3] |

| to Germany | 4,787 km2 | 19% | 9% | Posen-West Prussia[19] | [Note 4] |

| East Prussia | 37,002 km2[20] | 100% | 2.064.175 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 565 km2[21][22] | 2% | 2% | Pomeranian Voivodeship

(Soldauer Ländchen)[23] |

[Note 5] |

| to Lithuania | 2,828 km2 | 8% | 7% | Klaipėda Region | |

| to East Prussia

(within Weimar Germany) |

33,609 km2 | 90% | 91% | East Prussia | |

| Posen | 28,992 km2[20] | 100% | 2.099.831 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 26,111 km2[17] | 90%[18] | 93%[18] | Poznań Voivodeship | |

| to Germany | 2,881 km2 | 10% | 7% | Posen-West Prussia[19] | [Note 6] |

| Lower Silesia | 27,105 km2[25] | 100% | 3.017.981 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 526 km2[21][26] | 2% | 1% | Poznań Voivodeship

(Niederschlesiens Ostmark)[27] |

[Note 7] |

| to Germany | 26,579 km2 | 98% | 99% | Province of Lower Silesia | |

| Upper Silesia | 13,230 km2[25] | 100% | 2.207.981 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 3,225 km2[17] | 25% | 41%[17] | Silesian Voivodeship | [Note 8] |

| to Czechoslovakia | 325 km2[17] | 2% | 2%[17] | Hlučín Region | |

| to Germany | 9,680 km2[17] | 73% | 57%[17] | Province of Upper Silesia | |

| TOTAL | 131,909 km2 | 100% | 11.093.442 | Divided between: | |

| to Poland | 46,327 km2 | 35% | 35% | Second Polish Republic | [Note 9] |

| to Lithuania | 2,828 km2 | 2% | 2% | Klaipėda Region | |

| to Free City Danzig | 1,966 km2 | 2% | 3% | Free City of Danzig | |

| to Czechoslovakia | 325 km2 | 0% | 0% | Czech Silesia | |

| to Germany | 80,463 km2 | 61% | 60% | Free State of Prussia |

German annexation of Hultschin Area and the Memel Territory

In October 1938 Hlučín Area (Hlučínsko in Czech, Hultschiner Ländchen in German) of Moravian-Silesian Region which had been ceded to Czechoslovakia under the Treaty of Versailles was annexed by the Third Reich as a part of areas lost by Czechoslovakia in accordance with the Munich agreement. However, as distinct from other lost Czechoslovakian domains, it was not attached to Sudetengau (administrative region covering Sudetenland) but to Prussia (Upper Silesia).

By late 1938, Lithuania had lost control over the situation in the Memel Territory. In the early hours of 23 March 1939, after a political ultimatum caused a Lithuanian delegation to travel to Berlin, the Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Juozas Urbšys and his German counterpart Joachim von Ribbentrop signed the Treaty of the Cession of the Memel Territory to Germany in exchange for a Lithuanian Free Zone in the port of Memel, using the facilities erected in previous years.

In the interwar period the German administration, both Weimar and Nazi, conducted a massive campaign of renaming of thousands of placenames, to remove traces of Polish, Lithuanian and Old Prussian origin.

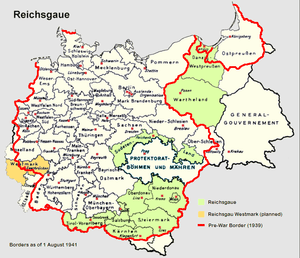

German occupation of Poland in World War II, 1939–1945

Between the two world wars, many in Germany claimed that the territory ceded to Poland in 1919–1922 should be returned to Germany. This claim was one of the justifications for the German invasion of Poland in 1939, heralding the start of the Second World War. The Third Reich annexed the former German lands, comprising the "Polish Corridor", West Prussia, the Province of Posen, and parts of eastern Upper Silesia. The council of the Free City of Danzig voted to become a part of Germany again, although Poles and Jews were deprived of their voting rights and all non-Nazi political parties were banned. In addition to taking territories lost in 1919, Germany also took additional land that had never been German.

Two decrees by Adolf Hitler (October 8 and October 12, 1939) divided the annexed areas of Poland into administrative units:

- Reichsgau Wartheland (initially Reichsgau Posen), which included the entire Poznań Voivodeship, most of the Łódź Voivodeship, five counties of the Pomeranian Voivodeship, and one county of the Warszawa Voivodeship;

- Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia (initially Reichsgau West Prussia), which consisted of the remaining area of the Pomeranian Voivodeship and the Free City of Danzig;

- Ciechanów District (Regierungsbezirk Zichenau), consisting of the five northern counties of Warszawa Voivodeship (Płock, Płońsk, Sierpc, Ciechanów, and Mława), which became a part of East Prussia;

- Katowice District (Regierungsbezirk Kattowitz), or East Upper Silesia (Ost-Oberschlesien), which included Sosnowiec, Będzin, Chrzanów, and Zawiercie Counties, and parts of Olkusz and Żywiec Counties.

These territories had an area of 94,000 km2 and a population of 10,000,000 people. Throughout the war, the annexed Polish territories were subject to German colonization. Because of the lack of settlers from Germany itself, the colonists were primarily ethnic Germans relocated from other parts of Eastern Europe. These ethnic Germans were then resettled in homes from which the Poles had been expelled.

The remainder of Polish territory was annexed by the Soviet Union (see Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact) or made into the German-controlled General Government occupation zone.

After the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the district of Białystok, which included the Białystok, Bielsk Podlaski, Grajewo, Łomża, Sokółka, Volkovysk, and Grodno Counties, was "attached to" (not incorporated into) East Prussia, whilst Eastern Galicia (District of Galicia), which included the cities of Lwów, Stanislawów and Tarnopol, was made part of the General Government.

The Yalta Conference

The final decision to move Poland's boundary westward was made by the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, shortly before the end of the war. The precise location of the border was left open; the western Allies also accepted in general the principle of the Oder River as the future western border of Poland and of population transfer as the way to prevent future border disputes. The open question was whether the border should follow the Eastern or Lusatian Neisse rivers, and whether Stettin, the traditional seaport of Berlin, should remain German or be included in Poland.

Originally, Germany was to retain Stettin while the Poles were to annex East Prussia with Königsberg.[29] Eventually, however, Stalin decided that he wanted Königsberg as a year-round warm water port for the Soviet Navy and argued that the Poles should receive Stettin instead. The wartime Polish government in exile had little to say in these decisions.[29]

.png)

At the Yalta Conference, it was agreed to split Germany into four occupation zones after the war, with a quadripartite occupation of Berlin as well, prior to unification of Germany. The status of Poland was discussed, but was complicated by the fact that Poland was at this time under the control of the Red Army. It was agreed to reorganize the Provisionary Polish Government that had been set up by the Red Army through the inclusion of other groups such as the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity and to have democratic elections. This effectively excluded the Polish government-in-exile that had evacuated in 1939. It was agreed that the Polish eastern border would follow the Curzon Line, and Poland would receive substantial territorial compensation in the west from Germany, although the exact border was to be determined at a later time. A "Committee on Dismemberment of Germany" was to be set up. The purpose was to decide whether Germany was to be divided into six nations, and if so, what borders and inter-relationships the new German states were to have.

Potsdam Agreement, 1945

Germany subsequently lost territories east of the Oder–Neisse Line at the end of the War in 1945, when international recognition of its right to jurisdiction over any of these territories was conditionally withdrawn. The "condition" mentioned was the Final German Peace Treaty, which was to set the actual border line, which might or might not deviate from the rivers Oder and Neisse. At Potsdam, the assumption by many was that a Final German Peace Treaty was imminent, but this turned out to be incorrect.

After World War II, as agreed at the Potsdam Conference (which met from 17 July until 2 August 1945), all of the areas east of the Oder–Neisse line, whether recognised by the international community as part of Germany until 1939 or occupied by Germany during World War II, were placed under the jurisdiction of other countries.The relevant paragraphs in the Potsdam Agreement are:[30][31][32]

V. City of Koenigsberg and the adjacent area.

The Conference examined a proposal by the Soviet Government to the effect that pending the final determination of territorial questions at the peace settlement, the section of the western frontier of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics which is adjacent to the Baltic Sea should pass from a point on the eastern shore of the Bay of Danzig to the east, north of Braunsberg-Goldap, to the meeting point of the frontiers of Lithuania, the Polish Republic and East Prussia.

The Conference has agreed in principle to the proposal of the Soviet Government concerning the (ultimate)[33] transfer to the Soviet Union of the City of Koenigsberg and the area adjacent to it as described above subject to expert examination of the actual frontier.

The President of the United States and the British Prime Minister have declared that they will support the proposal of the Conference at the forthcoming peace settlement.

VIII. Poland.

...

The British and United States Governments have taken measures to protect the interest of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity as the recognized government of the Polish State in the property belonging to the Polish State located in their territories and under their control, whatever the form of this property may be.

...

In conformity with the agreement on Poland reached at the Crimea Conference the three Heads of Government have sought the opinion of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity in regard to the accession of territory in the north and west which Poland should receive. The President of the National Council of Poland and members of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity have been received at the Conference and have fully presented their views. The three Heads of Government reaffirm their opinion that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement.

The three Heads of Government agree that, pending the final determination of Poland's western frontier, the former German territories east of a line running from the Baltic Sea immediately west of Swinamunde, and thence along the Oder River to the confluence of the western Neisse River and along the Western Neisse to the Czechoslovak frontier, including that portion of East Prussia not placed under the administration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in accordance with the understanding reached at this conference and including the area of the former free city of Danzig, shall be under the administration of the Polish State and for such purposes should not be considered as part of the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany. (Emphasis added)

The Allies also agreed that:

XII. Orderly transfer of German populations. The Three Governments [of the Soviet Union, the United States and Great Britain], having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner.

because in the words of Winston Churchill

Expulsion is the method which, in so far as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble. A clean sweep will be made.[34]

The problem with the status of these territories was that the Potsdam Agreement was not a legally binding treaty, but a memorandum between the USSR, the US and the UK (to which the French were not party). It regulated the issue of the eastern German border, which was confirmed as being along the Oder–Neisse line, but the final article of the memorandum said that the final decisions concerning Germany, and hence the detailed alignment of Germany's eastern boundaries, would be subject to a separate peace treaty; at which the three Allied signatories committed themselves to respect the terms of the Potsdam memorandum. Hence, so long as these Allied Powers remained committed to the Potsdam protocols, without German agreement to an Oder–Neisse line boundary there could be no Peace Treaty and no German Reunification. This treaty was signed in 1990 as the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany.[35][36]

Post World War II

After the War, the so-called "German question" was an important factor of post-war German and European history and politics. The debate affected Cold War politics and diplomacy and played an important role in the negotiations leading up to the reunification of Germany in 1990. In 1990 Germany officially recognized its present eastern border at the time of its reunification in the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, ending any residual claims to sovereignty that Germany may have had over any territory east of the Oder–Neisse line.

Between 1945 and the 1970s the government of West Germany referred to these territories as "former German territories temporarily under Polish and Soviet administration". This terminology was used in relation to territories of eastern Germany within the 1937 Germany border, and was based on the terminology used in the Potsdam Agreement. It was used only by the Federal Republic of Germany; but the Polish and Soviet governments objected to the obvious implication that these territories should someday revert to Germany. The Polish government preferred to use the phrase Recovered Territories, asserting a sort of continuity because parts of these territories had centuries previously been ruled by ethnic Poles.

Expulsion of Germans and resettlement

With the rapid advance of the Red Army in the winter of 1944–1945, German authorities desperately evacuated many Germans westwards. The majority of the remaining German-speaking population in the territory of former Czechoslovakia and east of the Oder–Neisse line (roughly 10 million in the ostgebiete alone), that had not already been evacuated, was expelled by the new Czech and Polish administrations. Although in the post-war period earlier German sources often cited the number of evacuated and expelled Germans at 16 million and the death toll at between 1.7[37] and 2.5 million,[38] today, the numbers are considered by some historians to be exaggerated and the death toll more likely in a range between 400,000 and 600,000.[39] Some present-day estimates place the numbers of German refugees at 14 million of which about half a million died during the evacuations and expulsions.[39][40]

At the same time, Poles from central Poland, expelled Poles from former eastern Poland, Polish returnees from internment and forced labour, Ukrainians forcibly resettled in Operation Vistula, and Jewish Holocaust survivors were settled in German territories gained by Poland, whereas the north of former East Prussia (Kaliningrad Oblast gained by the USSR) was turned into a military zone and subsequently settled with Russians.

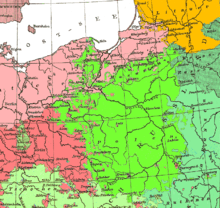

Origins of post-war inhabitants of areas annexed by Poland

During the Polish post-war census of December 1950, data about the pre-war places of residence of the inhabitants as of August 1939 was collected. In case of children born between September 1939 and December 1950, their place of residence was reported based on the pre-war places of residence of their mothers. Thanks to this data it is possible to reconstruct the pre-war geographical origin of the post-war population in the Recovered Territories of Poland . Many areas located near the pre-war German border were resettled by people from neighbouring borderland areas of pre-war Poland. For example, Kashubians from pre-war Polish Corridor settled in nearby areas of German Pomerania adjacent to Polish Pomerania. People from Poznań region of pre-war Poland settled in East Brandenburg. People from East Upper Silesia moved into the rest of Silesia. And people from Masovia and from Sudovia moved into adjacent Masuria. Poles expelled from former Polish territories in the east (today mainly parts of Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania) settled in large numbers everywhere in the Recovered Territories (but many of them also settled in central Poland).

| Region (within 1939 borders): | West Upper Silesia | Lower Silesia | East Brandenburg | West Pomerania | Free City Danzig | South East Prussia | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autochthons (1939 DE/FCD citizens) | 789,716 | 120,885 | 14,809 | 70,209 | 35,311 | 134,702 | 1,165,632 |

| Polish expellees from Kresy (USSR) | 232,785 | 696,739 | 187,298 | 250,091 | 55,599 | 172,480 | 1,594,992 |

| Poles from abroad except the USSR | 24,772 | 91,395 | 10,943 | 18,607 | 2,213 | 5,734 | 153,664 |

| Resettlers from the City of Warsaw | 11,333 | 61,862 | 8,600 | 37,285 | 19,322 | 22,418 | 160,820 |

| From Warsaw region (Masovia) | 7,019 | 69,120 | 16,926 | 73,936 | 22,574 | 158,953 | 348,528 |

| From Białystok region and Sudovia | 2,229 | 23,515 | 3,772 | 16,081 | 7,638 | 102,634 | 155,869 |

| From pre-war Polish Pomerania | 5,444 | 54,564 | 19,191 | 145,854 | 72,847 | 83,921 | 381,821 |

| Resettlers from Poznań region | 8,936 | 172,163 | 88,427 | 81,215 | 10,371 | 7,371 | 368,483 |

| Katowice region (East Upper Silesia) | 91,011 | 66,362 | 4,725 | 11,869 | 2,982 | 2,536 | 179,485 |

| Resettlers from the City of Łódź | 1,250 | 16,483 | 2,377 | 8,344 | 2,850 | 1,666 | 32,970 |

| Resettlers from Łódź region | 13,046 | 96,185 | 22,954 | 76,128 | 7,465 | 6,919 | 222,697 |

| Resettlers from Kielce region | 16,707 | 141,748 | 14,203 | 78,340 | 16,252 | 20,878 | 288,128 |

| Resettlers from Lublin region | 7,600 | 70,622 | 19,250 | 81,167 | 19,002 | 60,313 | 257,954 |

| Resettlers from Kraków region | 60,987 | 156,920 | 12,587 | 18,237 | 5,278 | 5,515 | 259,524 |

| Resettlers from Rzeszów region | 23,577 | 110,188 | 13,147 | 57,965 | 6,200 | 47,626 | 258,703 |

| place of residence in 1939 unknown | 36,834 | 26,586 | 5,720 | 17,891 | 6,559 | 13,629 | 107,219 |

| Total pop. in December 1950 | 1,333,246 | 1,975,337 | 444,929 | 1,043,219 | 292,463 | 847,295 | 5,936,489 |

Ostpolitik

In the 1970s, West Germany adopted Ostpolitik in foreign relations, which strove to normalise relations with its neighbours by recognising the realities of the European order of the time,[42] and abandoning elements of the Hallstein Doctrine. West Germany also abandoned for the time being its claims with respect to German self-determination and reunification, recognising the existence of the German Democratic Republic (GDR); and the validity of the Oder–Neisse line in international law."[42] As part of this new approach, West Germany concluded friendship treaties with the Soviet Union (Treaty of Moscow (1970)), Poland (Treaty of Warsaw (1970)), East Germany (Basic Treaty (1972)) and Czechoslovakia (Treaty of Prague (1973)); and participated in the Helsinki Final Act (1975). Nevertheless, West Germany continued its long term objective of achieving a reunification of East Germany, West Germany and Berlin; and maintained that its formal recognition of the post-war boundaries of Germany would need to be confirmed by a united Germany in the context of a Final Settlement of the Second World War. Some West German commentators continued to maintain that neither the Treaty of Zgorzelec nor the Treaty of Warsaw should be considered as binding on a future united Germany; albeit that these reservations were intended for domestic political consumption, and the arguments advanced in support of them had no substance in international law.

Present status

Over time, the "German question" has been muted by a number of related phenomena:

- The passage of time resulted in fewer people being left who have firsthand experience of living in these regions under German jurisdiction.

- In the Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany, Germany renounced all claims to territory east of the Oder–Neisse line. Germany's recognition of the border was repeated in the German–Polish Border Treaty on November 14, 1990. The treaties were made by both German states and ratified in 1991 by a united Germany.

- The expansion of the European Union towards east in 2004 enabled any German wishing to live and work in Poland, and thus east of the Oder–Neisse line, to do so without requiring a permit. German expellees and refugees became free to visit their former homes and set up residence, though some restrictions remained on the purchase of land and buildings.

- Poland entered the Schengen Area on December 21, 2007, removing all border controls on its border with Germany.

Under Article 1 of the Treaty on Final Settlement, the new united, Germany committed itself to renouncing any further territorial claims beyond the boundaries of East Germany, West Germany and Berlin; "The united Germany has no territorial claims whatsoever against other states and shall not assert any in the future." Furthermore, the Basic Law of the Federal Republic was required to be amended to state explicitly that full German unification had now been achieved, such that the new German state comprised the entirety of Germany, and that all constitutional mechanisms should be removed by which any territories outside those boundaries could otherwise subsequently be admitted; these new constitutional articles being bound by treaty not to be revoked. Article 23 of the Basic Law was repealed, closing off the possibility for any further states to apply for membership of the Federal Republic; while Article 146 was amended to state explicitly that the territory of the newly unified republic comprised the entirety of the German people; "This Basic Law, which since the achievement of the unity and freedom of Germany applies to the entire German people, shall cease to apply on the day on which a constitution freely adopted by the German people takes effect". This was confirmed in the 1990 rewording of the preamble; "Germans..have achieved the unity and freedom of Germany in free self-determination. This Basic Law thus applies to the entire German people." In place of the former Article 23 (under which the states of East Germany had been admitted), a new Article 23 established the constitutional status of accession of the Federal Republic to the European Union; hence with the subsequent accession of Poland to the EU, the constitutional bar on pursuing any claim to territories beyond the Oder–Neisse Line was reinforced. In so far as the former German Reich may be claimed to continue in existence within 'Germany as a whole', former eastern German territories in Poland and Russia are now definitively and permanently excluded from ever again being united with Germany.

In the course of the German reunification, Chancellor Helmut Kohl accepted the territorial changes made after World War II, creating some outrage among the Federation of Expellees, while some Poles were concerned about a possible revival of their 1939 trauma through a "second German invasion", this time with the Germans buying back their land, which was cheaply available at the time. This happened on a smaller scale than many Poles expected, and the Baltic Sea coast of Poland has become a popular German tourist destination. The so-called "homesickness-tourism" which was often perceived as quite aggressive well into the 1990s now tends to be viewed as a good-natured nostalgia tour rather than an expression of anger and desire for the return of the lost territories.

Some organisations in Germany continue to claim the territories for Germany or property there for German citizens. The Prussian Trust (or the Prussian Claims Society), that probably has less than a hundred members,[43] re-opened the old dispute when in December 2006, it submitted 23 individual claims against the Polish government to the European Court of Human Rights asking for compensation or return of property appropriated from its members at the end of World War II. An expert report jointly commissioned by the German and Polish governments from specialists in international law have confirmed that the proposed complaints by the Prussian Trust had little hope of success. But the German government cannot prevent such requests being made and the Polish government has felt that the submissions warranted a comment by Anna Fotyga, the Polish Minister of the Foreign Affairs to "express [her] deepest concern upon receiving the information about a claim against Poland submitted by the Prussian Trust to the European Court of Human Rights".[44] On 9 October 2008 the European Court of Human Rights declared the case of Preussische Treuhand v. Poland inadmissible, because the European Convention on Human Rights does not impose any obligations on the Contracting States to return property which was transferred to them before they ratified the Convention.[45]

After the National Democratic Party of Germany, described as a neo-Nazi organisation, won six seats in the parliament of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in September 2006, the leader of the party, Udo Voigt, declared that his party demands Germany in "historical borders" and questioned the current border treaties.[46]

Former eastern territories in German history

Important events from German history include battles such as Frederick the Great’s victories at Mollwitz in 1741, Hohenfriedberg in 1745, Leuthen (1757) and Zorndorf (1758), and his defeats at Gross-Jägersdorf in 1757 and Kunersdorf in 1759. Historian Norman Davies describes Kunersdorf as "Prussia's greatest disaster" and the inspiration for Christian Tiedge's Elegy to "Humanity butchered by Delusion on the Altar of Blood".[47] In the Napoleonic Wars the Pomeranian town of Kolberg was besieged in 1807 (inspiring a Second World War Nazi propaganda film) while the French Grande Armée was victorious at Eylau in East Prussia in the same year. The Treaties of Tilsit were separately signed in the selfsame town in July 1807 between Napoleon and the Russians and Prussians. The Iron Cross, Germany's highest military honour, was established (though not awarded) by King Frederick William III at Breslau on 17 March 1813.[48] In World War I, Hindenburg won critical victories at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, ejecting Russian forces from East Prussia.[47]

See also

- List of people from former eastern territories of Germany

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- History of German settlement in Central and Eastern Europe

- Ostsiedlung

- Drang nach Osten

- Major treaties affecting the former eastern territories of Germany:

- World War II evacuation and expulsion

- Expulsion of Poles by Germany

- Evacuation, flight and expulsion of Germans from those territories:

- Evacuation of German civilians during the end of World War II

- Evacuation of East Prussia

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50)

- Flight and expulsion of Germans from Poland during and after World War II

- Polish population transfers (1944–1946)

Notes

- The region is called Western Pomerania in Polish historiography and Farther Pomerania in German historiography.

- Poland received several cities and counties of West Prussia located east of the Vistula: Lubawa, Brodnica, Wąbrzeźno, Toruń, Chełmno, Grudziądz; as well as most of cities and counties of West Prussia located west of it: Świecie, Tuchola, Starogard Gdański, Kwidzyn (only part west of the Vistula), most of county Tczew, eastern part of county Złotów, part of county Człuchów, as well as counties Chojnice, Kościerzyna, Kartuzy, coastal Wejherowo and Puck with Gdynia; as well as a small western part of Danziger Höhe and areas around Janowo east of the Vistula.

- Parts of West Prussia east of Nogat and Vistula rivers which remained in Germany after 1918, including the city and county of Elbląg and counties Malbork (part east of Nogat), Sztum, Kwidzyn (only part east of the Vistula) and Susz were incorporated to East Prussia as the Regency of West Prussia. The area of historical Pomesania had significant Polish minority.

- Western part of West Prussia with county Wałcz and parts of counties Złotów and Człuchów (the latter two split between Poland and Germany). This area included 12 towns and cities: Człuchów, Debrzno, Biały Bór, Czarne, Lędyczek, Złotów, Krajenka, Wałcz, Mirosławiec, Człopa, Tuczno and Jastrowie. The area was home to significant Polish minority.

- Part of pre-1918 county Nidzica with Działdowo and with around 27 thousand inhabitants;[21] as well as parts of county Ostróda near Dąbrówno, with areas around Groszki, Lubstynek, Napromek, Czerlin, Lewałd Wielki, Grzybiny and with around 4786 inhabitants.[24] Too small to form its own voivodeship, this territory was incorporated to intewar Pomeranian Voivodeship.

- Western fringes of Prussian Greater Poland, which remained in Germany after 1918. This area included entire county Skwierzyna as well as portions of counties Wschowa, Babimost, Międzyrzecz, Chodzież, Wieleń and Czarnków (Netzekreis). It contained 12 towns and cities: Piła, Skwierzyna, Bledzew, Wschowa, Szlichtyngowa, Babimost, Kargowa, Międzyrzecz, Zbąszyń, Brójce, Trzciel and Trzcianka. The area was home to significant Polish minority.

- After World War 1 Poland received a small part of historical Lower Silesia, with majority ethnic Polish population as of year 1918. That area included parts of counties Syców (German: Polnisch Wartenberg), Namysłów, Góra and Milicz. In total around 526 square kilometers with around 30 thousand[17][21] inhabitants, including the city of Rychtal. Too small to form its own voivodeship, the area was incorporated to Poznań Voivodeship (former Province of Posen).

- Interwar Silesian Voivodeship was formed from Prussian East Upper Silesia (area 3,225 km2) and Polish part of Austrian Cieszyn Silesia (1,010 km2), in total 4,235 km2. After the annexation of Zaolzie from Czechoslovakia in 1938, it increased to 5,122 km2.[28] Silesian Voivodeship's capital was Katowice.

- All in all, the post-Prussian part of Poland had ca. 4 million inhabitants immediately after the Great War - ca. 2 million from Province of Posen, ca. 1 million from West Prussia and ca. 1 million from Upper Silesia, plus 60,000 from Lower Silesia and East Prussia.

References

- Kozicki, Stanislas (1918). The Poles under Prussian rule. Toronto: London, Polish Press Bur.

- Demshuk, Andrew. The Lost German East: Forced Migration and the Politics of Memory, 1945-1970. page 52

- see for example msn encarta Archived 2009-10-31 at WebCite: "diejenigen Gebiete des Deutschen Reiches innerhalb der deutschen Grenzen von 1937", Meyers Lexikon online Archived 2009-01-26 at the Wayback Machine: "die Teile des ehemaligen deutschen Reichsgebietes zwischen der Oder-Neiße-Linie im Westen und der Reichsgrenze von 1937 im Osten".

- Hammer, Eric (2013). "Ms. Livni, Remember the Recovered Territories. There is an historical precedent for a workable solution". Arutz Sheva.

- The problem with the status of these territories was that in 1945 the concluding document of the Potsdam Conference was not a legally binding treaty, but a memorandum between the USSR, the US and the UK. It regulated the issue of the eastern German border, which was to be the Oder–Neisse line, but the final article of the memorandum said that the final decisions concerning Germany were subject to a separate peace treaty. This treaty was signed in 1990 under the name of Treaty on the Final Settlement by both the German states and ratified in 1991 by the united Germany. This ended the legal limbo state which meant that for 45 years, people on both sides of the border could not be sure whether the settlement reached in 1945 might be changed at some future date.

- Cornfield, Daniel B. and Hodson, Randy (2002). Worlds of Work: Building an International Sociology of Work. Springer, p. 223. ISBN 0306466058

- Pollock, Michael. Östereichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie; Zeitschrift für Soziologie, Jg. 8, Heft 1 (1979); 50-62. 01/1979 (in German)

- Baranowsky, Shelley (1995). The Sanctity of Rural Life: Nobility, Protestantism, and Nazism in Weimar Prussia. Oxford University Press, pp. 187-188. ISBN 0195361660

- Schmitt, Carl (1928). Political Romanticism. Transaction Publishers. Preface, p. 11. ISBN 1412844304

- "Each spring, millions of workmen from all parts of western Russia arrived in eastern Germany, which, in political language, is called East Elbia." Viereck, George Sylvester. The Stronghold of Junkerdom, Volume 8. Fatherland Corporation, 1918

- The public broadcaster run by the states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia is Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (lit. in English: Middle German broadcast), the regional newspaper issued in Halle upon Saale is the Mitteldeutsche Zeitung, and a Protestant regional church body in the area, just recently founded by a merger, is the Evangelische Kirche in Mitteldeutschland (English: Protestant Church in Middle Germany).

- Tadeusz Gasztold, Hieronim Kroczyński, Hieronim Rybicki, Kołobrzeg: zarys dziejów, Wydaw. Poznańskie, 1979, p. 27 (in Polish)

- "Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa - biblioteka cyfrowa regionu śląskiego - Wznowione powszechne taxae-stolae sporządzenie, Dla samowładnego Xięstwa Sląska, Podług ktorego tak Auszpurskiey Konfessyi iak Katoliccy Fararze, Kaznodzieie i Kuratusowie Zachowywać się powinni. Sub Dato z Berlina, d. 8. Augusti 1750". Sbc.org.pl. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- Hugo Weczerka, Handbuch der historischen Stätten: Schlesien, 2003, p.XXXVI, ISBN 3-520-31602-1

- M. Czapliński [in:] M. Czapliński (red.) Historia Śląska, Wrocław 2007, s. 290

- Ernst Badstübner, Dehio - Handbuch der Kunstdenkmäler in Polen: Schlesien, 2003, p.4, ISBN 3-422-03109-X

- Weinfeld, Ignacy (1925). Tablice statystyczne Polski: wydanie za rok 1924 [Poland's statistical tables: edition for year 1924]. Warsaw: Instytut Wydawniczy "Bibljoteka Polska". p. 2.

- Nadobnik, Marcin (1921). "Obszar i ludność b. dzielnicy pruskiej [Area and population of former Prussian district]" (PDF). Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny. Poznań. 1 (3) – via AMUR - Adam Mickiewicz University Repository.

- "Die Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen Übersichtskarte". Gonschior.de.

- "Gemeindeverzeichnis Deutschland".

- "Rocznik statystyki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 1920/21". Rocznik Statystyki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (in Polish and French). Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. I: 56–62. 1921.

- Jehke, Rolf. "Rbz. Allenstein: 10.1.1920 Abtretung des Kreises Neidenburg (teilweise) an Polen; 15.8.1920 Abtretung der Landgemeinden Groschken, Groß Lehwalde (teilweise), Klein Lobenstein (teilweise), Gut Nappern und der Gutsbezirke Groß Grieben (teilweise) und Klein Nappern (teilweise) an Polen". territorial.de.

- "Działdowo, Soldauer Gebiet, Soldauer Ländchen". GOV The Historic Gazetteer.

- Khan, Daniel-Erasmus (2004). Die deutschen Staatsgrenzen. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 78. ISBN 3-16-148403-7.

- "Gemeindeverzeichnis Deutschland: Schlesien".

- "Schlesien: Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert". OME-Lexikon - Universität Oldenburg.

- Sperling, Gotthard Hermann (1932). "Aus Niederschlesiens Ostmark" (PDF). Opolska Biblioteka Cyfrowa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- Mały Rocznik Statystyczny [Little Statistical Yearbook] 1939 (PDF). Warsaw: GUS. 1939. p. 14.

- (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20131101211017/http://newyorktelco.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/biuletyn9-10_56-57.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003). "Potsdam Agreement, 1945". In Mango, Anthony (ed.). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: A to F. 1. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1829–1830. ISBN 9780415939218.

- Krickus, Richard J. (202). The Kaliningrad Question (illustrated ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 34–35. ISBN 9780742517059.

- Piotrowicz, Ryszard W.; Blay, Sam; Schuster, Gunnar; Zimmermann, Andreas (1997). "The Unification of Germany in International and Domestic Law". German Monitor. Rodopi (39): 48–49. ISBN 9789051837551. ISSN 0927-1910.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- 'ultimate' not present in the official Russian text

- Murphy, Clare (2004-08-02). "WWII expulsions spectre lives on". BBC News. bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Junker, Detlef; Gassert, Philipp; Mausbach, Wilfried; et al., eds. (2004). The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945-1990: A Handbook. Publications of the German Historical Institute Volume 1 of The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War 2 Volume Set (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780521791120.

- Piotrowicz et al. 1997, p. 66.

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler (2003). Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte Band 4: Vom Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges bis zur Gründung der beiden deutschen Staaten 1914–1949 (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck Verlag. ISBN 3-406-32264-6.

- Dagmar Barnouw (2005). The War in the Empty Air: Victims, Perpetrators, and Postwar Germans. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 143. ISBN 0-253-34651-7.

- Frank Biess (2006). "Review of Dagmar Barnouw, The War in the Empty Air: Victims, Perpetrators, and Postwar Germans". H-Net Reviews: 2. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- Rüdiger Overmans (2004). Deutsche militärische Verluste im Zweiten Weltkrieg (German Military Losses in WWII) (in German). Munich: Oldenbourg. pp. 298–300. ISBN 3-486-56531-1.

- Kosiński, Leszek (1960). "Pochodzenie terytorialne ludności Ziem Zachodnich w 1950 r. [Territorial origins of inhabitants of the Western Lands in year 1950]" (PDF). Dokumentacja Geograficzna (in Polish). Warsaw: PAN (Polish Academy of Sciences), Institute of Geography. 2: Tabela 1 (data by county) – via Repozytorium Cyfrowe Instytutów Naukowych.

- The Federal Republic of Germany's Ostpolitik, the European Navigator

- Klaus Ziemer. What Past, What Future? Social Science in Eastern Europe: News letter: Special Issue German-Polish Year 2005/2006 Archived 2007-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, 2005 Issue 4, ISSN 1615-5459 pp. 4–11 (See page 4). Published by the Social Science Information Centre (see Archive Archived 2007-06-06 at the Wayback Machine)

- Anna Fotyga, the Polish Minister of the Foreign Affairs "I express my deepest concern upon receiving the information about a claim against Poland submitted by the Prussian Trust to the European Court of Human Rights. ...". 21 December 2006

- Decision as to the admissibility Application no. 47550/06 by Preussische Treuhand GMBH & CO. KG A. A. against Poland, by the European Court of Human Rights, 7 October 2008

- (in Polish)Szef NPD: chcemy Niemiec w historycznych granicach, 22 września 2006, gazeta.pl

- Davies, N. (2005) God's Playground. A History of Poland. Volume II: 1795 to the present. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Michael Nungesser. Das Denkmal auf dem Kreuzberg von Karl Friedrich Schinkel, ed. on behalf of the Bezirksamt Kreuzberg von Berlin as catalogue of the exhibition „Das Denkmal auf dem Kreuzberg von Karl Friedrich Schinkel" in the Kunstamt Kreuzberg / Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, between 25 April and 7 June 1987, Berlin: Arenhövel, 1987, p. 29. ISBN 3-922912-19-2.

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Emotions prevail in relations between Germans, Czechs, Poles – poll, Czech Happenings, 21 December 2005

- Jose Ayala Lasso. Speech to the German expellees, Day of the Homeland, Berlin 6 August 2005 Lasso was the first United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (1994–1997)

- Ryszard W. Piotrowicz. The Status of Germany in International Law: Deutschland uber Deutschland? The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 3 (Jul., 1989), pp. 609–635 "The purpose of this article is to consider the legal status of Germany from 1945 to [1989]"