Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

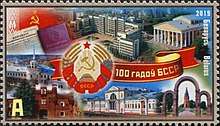

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; Belarusian: Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, romanized: Biełaruskaja Savjetskaya Satsyjalistichnaya Respublika; Russian: Белорусская Советская Социалистическая Республика, romanized: Belorusskaya Sovjetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika or Russian: Белорусская ССР, romanized: Belorusskaya SSR), also commonly referred to in English as Byelorussia, was a federal unit of the Soviet Union (USSR). It existed between 1920 and 1922, and from 1922 to 1991 as one of fifteen constituent republics of the USSR, with its own legislation from 1990 to 1991. The republic was ruled by the Communist Party of Byelorussia and was also referred to as Soviet Byelorussia by a number of historians.[3]

Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка (Belarusian) Белорусская Советская Социалистическая Республика (Russian) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920–1991 1941–1944: German occupation | |||||||||||||||||

Motto: Пралетарыі ўсіх краін, яднайцеся! (Belarusian) Praletaryi ŭsikh krain, yadnaytsesya! (transliteration) "Workers of the world, unite!" | |||||||||||||||||

Anthem: Дзяржаўны гімн Беларускай Савецкай Сацыялiстычнай Рэспублiкi Dziaržaŭny himn Biełaruskaj Savieckaj Sacyjalistyčnaj Respubliki "Anthem of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic" (1952–1991) | |||||||||||||||||

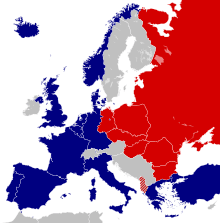

Location of Byelorussia (red) within the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Soviet Socialist Republic (1922–1990) Union republic with | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Minsk | ||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||||||||

| Recognised languages | |||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Byelorussian, Soviet | ||||||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||||||

| First Secretary | |||||||||||||||||

• 1920–1923 (first) | Vilgelm Knorinsh | ||||||||||||||||

• 1990–1991 (last) | Anatoly Malofeyev | ||||||||||||||||

| Head of state | |||||||||||||||||

• 1920–1937 (first) | Alexander Chervyakov | ||||||||||||||||

• 1990–1991 (last) | Nikolay Dementey | ||||||||||||||||

| Head of government | |||||||||||||||||

• 1920–1924 (first) | Alexander Chervyakov | ||||||||||||||||

• 1990–1991 (last) | Vyacheslav Kebich | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Supreme Soviet | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | 20th century | ||||||||||||||||

• Republic declared | 1 January 1919 | ||||||||||||||||

• Soviet republic proclaimed | 31 July 1920 | ||||||||||||||||

| 30 December 1922 | |||||||||||||||||

| 15 November 1939 | |||||||||||||||||

| 24 October 1945 | |||||||||||||||||

• Sovereignty declared (partial end of Soviet laws) | 27 July 1990 | ||||||||||||||||

• Independence declared | 25 August 1991 | ||||||||||||||||

• Renamed Republic of Belarus | 19 September 1991 | ||||||||||||||||

• Internationally recognized (Dissolution of the Soviet Union) | 26 December 1991 | ||||||||||||||||

| 15 March 1994 | |||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

• Total | 207,600 km2 (80,200 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

| 10,199,709 | |||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Soviet ruble (руб) (SUR) | ||||||||||||||||

| Calling code | 7 015/016/017/02 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Belarus |

.svg.png)  |

| Prehistory |

| Middle ages |

| Early Modern |

|

| Modern |

|

|

|

| Eastern Bloc | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

|

Allied states

|

|||||||

|

Related organizations |

|||||||

|

Dissent and opposition

|

|||||||

To the west it bordered Poland. Within the Soviet Union, it bordered the Lithuanian SSR and the Latvian SSR to the north, the Russian SFSR to the east, and the Ukrainian SSR to the south.

The Socialist Soviet Republic of Byelorussia (SSRB) was declared by the Bolsheviks on 1 January 1919 following the declaration of independence by the Belarusian Democratic Republic in March 1918. In 1922, the BSSR was one of the four founding members of the Soviet Union, together with the Ukrainian SSR, the Transcaucasian SFSR, and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). Byelorussia was one of several Soviet republics occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II.

Towards the final years of the Soviet Union's existence, the Supreme Soviet of Byelorussian SSR adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty on 27 July 1990. On 15 August 1991, Stanislaŭ Šuškievič was elected as the country's first head of state. Ten days later on 25 August 1991, Byelorussian SSR declared its independence and renamed to the Republic of Belarus. The Soviet Union was dissolved four months and one day later on 26 December 1991.

Terminology

The term Byelorussia (Russian: Белору́ссия, derives from the term Belaya Rus' , i.e., White Rus'. There are several claims to the origin of the name White Rus'.[4] An ethno-religious theory suggests that the name used to describe the part of old Ruthenian lands within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that had been populated mostly by early Christianized Slavs, as opposed to Black Ruthenia, which was predominantly inhabited by pagan Balts.[5]

The latter part similar but spelled and stressed differently from Росси́я, Russia) first rose in the days of the Russian Empire, and the Russian Tsar was usually styled "the Tsar of All the Russias", as Russia or the Russian Empire was formed by three parts of Russia—the Great, Little, and White.[6] This asserted that the territories are all Russian and all the peoples are also Russian; in the case of the Belarusians, they were variants of the Russian people.[7]

Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the term "White Russia" caused some confusion as it was also the name of the military force that opposed the red Bolsheviks.[8] During the period of the Byelorussian SSR, the term Byelorussia was embraced as part of a national consciousness. In western Belarus under Polish control, Byelorussia became commonly used in the regions of Białystok and Hrodna during the interwar period.[9] Upon the establishment of the Byelorussian Socialist Soviet Republic in 1920, the term Byelorussia (its names in other languages such as English being based on the Russian form) was only used officially. In 1936, with the proclamation of the 1936 Soviet Constitution, the republic was renamed to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic transposing the second ("socialist") and third ("soviet") words.

On 25 August 1991 the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian SSR renamed the Soviet republic to the Republic of Belarus, with the short form "Belarus". Conservative forces in the newly independent Belarus did not support the name change and opposed its inclusion in the 1991 draft of the Constitution of Belarus.[10]

History

Beginning

Prior to the First World War, Belarusian lands were part of the Russian Empire, which it gained from the Partitions of Poland more than a century earlier. During the War, the Russian Western Front's Great retreat in August/September 1915 ended with the lands of Hrodna and most of Viĺnia guberniyas occupied by Germany. The resulting front, passing at 100 kilometres to the west of Minsk remained static towards the end of the conflict, despite Russian attempts to break it at Lake Narač in late spring 1916 and General Alexei Evert's inconclusive thrust around the city of Baranavičy in summer of that year, during the Brusilov offensive further south, in Western Ukraine.

The abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in light of the February Revolution in Russia in February 1917, activated a rather dormant political life in Belarus. As central authority waned, different political and ethnic groups strived for greater self-determination and even secession from the increasingly ineffective Russian Provisional Government. The momentum picked up after the incompetent actions of the 10th Army during the ill-fated Kerensky Offensive during the summer. Representatives of Belarusian regions and of different (mostly left-wing) newly established political powers, including the Belarusian Socialist Assembly, the Christian democratic movement and the General Jewish Labour Bund, formed a Belarusian Central Council.

Towards the autumn political stability continued to shake, and countering the rising nationalist tendencies were the Bolshevik Soviets, when the October Revolution hit Russia, that same day, on 25 October (7 November), the Minsk Soviet of workers and soldiers deputies took over the administration of the city. The Bolshevik All-Russian council of Soviets declared the creation of the Western Oblast which unified the Viĺnia, Viciebsk, Mahilioŭ and Minsk guberniyas that were not occupied by the German army, to administer the Belarusian lands in the frontal zone. On 26 November (6 December), the executive committee of workers, peasants and soldiers deputies for the Western Oblast was merged with the Western front's executive committee, creating a single Obliskomzap. During the autumn 1917/winter of 1918, the Western Oblast was headed by Aleksandr Myasnikyan as head of the Western Oblast's Military Revolutionary Committee, who passed this duty on to Karl Lander. Myasnikyan took over as chair of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party's (RSDRP(b)) committee for Western Oblast and Maisiej Kaĺmanovič as chair of the Obliskomzap.

Countering this the Belarusian Central Council reorganised itself as a Belarusian National Council (Rada) and started working on establishing governmental institutions, and discarded the Obliskomzap as a military formation, rather than governmental. As a result, on 7th (20th) of December, when the first All-Belarusian congress convened, the Bolsheviks forcibly disbanded it.

German involvement

Although German espionage played a key role in bringing the October Revolution to Russia, and one of the first decrees issued by the new government was the Decree on Peace de facto fulfilling the promise of ending Russia's role in World War I, the Russo-German front in Belarus remained static since 1915 and formal negotiations began only on 19 November (2 December N.S.), when the Soviet delegation traveled to the German-occupied Belarusian city of Brest-Litoŭsk. A cease-fire was quickly agreed and proper peace negotiations began in December.

However, the German party soon went back on its word and took full advantage of the situation, and the Bolsheviks' demand of a treaty "without annexations or indemnities" was unacceptable to the Central Powers, and on 18 February hostilities resumed. The German Operation Faustschlag was of immediate success and within 11 days, they were able to make a serious advance eastward, taking over Ukraine, the Baltic states and occupying Eastern Belarus. This forced the Obliskomzap to evacuate to Smolensk. The Smolensk guberniya was passed to the Western Oblast.

Faced with the German demands, the Bolsheviks accepted their terms at the final Treaty of Brest-Litoŭsk, which was signed on 3 March 1918. For the German Empire, Operation Faustschlag achieved one of their strategic plans for World War I, to create a German-centered hegemony of buffer states, called Mitteleuropa. Support of local nationalist groups alienated by Bolsheviks was key, thus, when four days after Minsk was occupied by the German Army, the disbanded Belarusian National Council declared itself as the sole authority in Belarus, the Germans stood by, and recognised the declared Belarusian Democratic Republic on 25 March.

Creation

After Germany was defeated in the First World War, it announced its evacuation from the occupied territories of Belarus and Ukraine. As the Germans were preparing to depart, the Bolsheviks were keen to enter the territory to re-claim Belarus, Ukraine, and the Baltics to realise Soviet premier Vladimir Lenin's advocacy to seize the territories of the former Russian Empire and advance the world revolution.

On 11 September 1918, the Revolutionary Military Council ordered the creation of the Western Defence region in the Western Oblast out of Curtain forces which were stationed there. Simultaneously the Council reorganised the Western Oblast as a Western Commune. On 13 November, Moscow annulled the Treaty of Brest-Litoŭsk. Two days later it transformed the Defence region into a Western army. It began an initially bloodless advance westward on the 17th. The Belarusian National Republic barely resisted, evacuating Minsk on 3 December. The Soviets maintained a distance of about 10–15 kilometres (6.2–9.3 mi) between the two armies,[11] and took Minsk on the 10th.

Encouraged by their success, in Smolensk on 30–31 December 1918, the Sixth Western Oblast Party conference met and announced its split from the Russian Communist Party, proclaiming itself as the first congress of the Communist Party of Byelorussia (CPB(b)). The next day, the Soviet Socialist Republic of Byelorussia was proclaimed in Smolensk, terminating the Western Commune, and on 7 January it was moved to Minsk. Aleksandr Myasnikyan emerged as head of the All-Byelorussian Central Executive Committee and Zmicier Žylunivič as head of the provisional government.

The new Soviet republic initially consisted of seven districts: Baranavičy, Viciebsk, Homieĺ, Hrodna, Mahilioŭ and Smolensk. On 30 January, the republic announced its separation from the Russian SFSR and renaming as the Soviet Socialist Republic of Byelorussia (SSRB). This was conferred by the First Congress of deputies, composed of workers, soldiers and Red Army men, which met on 2–3 February 1919, to adopt a new Socialist constitution. The Red Army continued its westward advance, capturing the city of Grodno on New Year's Day 1919, Pinsk on 21 January, and Baranovichi on 6 February 1919, thereby enlarging the SSRB.

Litbel

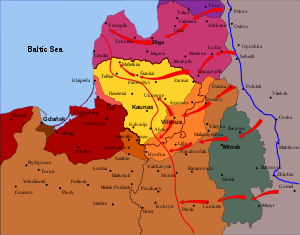

The western winter offensive described above was not limited to Byelorussia; Soviet forces similarly moved to the north into Lithuania. On 16 December the Lithuanian Socialist Soviet Republic (LSSR) was proclaimed in Vilnius.

The Lithuanian operation and continuing conquest of Byelorussia were threatened by the rise of the Second Polish Republic after the withdrawal of German forces. However the conflict with Poland did not break out and the Soviet High Command's 12 January directive was to cease advance on the Neman-Bug rivers. However, the region to the east of those lines was historically mixed among a population of Belarusians, Poles and Lithuanians, with a sizeable Jewish minority. The local communities of each respective group wanted to be part of the respective states that were establishing themselves.

In the Kresy ("Borderland") areas of Lithuania, Belarus and western Ukraine, self-organized militias, the Samoobrona Litwy i Białorusi numbering approximately 2,000 soldiers under General Wejtko, began to fight against the local communist and advancing Bolshevik forces. Each side was trying to secure the territories for its own government. The newly formed Polish Army began sending its organised units to reinforce the militias. On 14 February, the first clash between regular armies took place and a front emerged.

Eager to win support, the Bolshevik government decided to restore the Great Duchy of Lithuania by merging the Lithuanian and Byelorussian republics into the Lithuanian–Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, or Litbel on 28 February 1919. Its capital was proclaimed as Vilnius, with five guberniyas: Vilno, Grodno, Kovno, Suwalki and Minsk. The Vitebsk and Mogilev guberniyas were transferred to the Russian SFSR, and were soon joined by the Gomel Governorate, which was created on 26 April.

The operations in Lithuania brought the front close to East Prussia, and the German units that had withdrawn there began to assist the Lithuanian forces to defeat the Soviets; they repelled the Red offensive against Kaunas in February 1919.

In March 1919, Polish units opened an offensive: forces under General Stanisław Szeptycki captured the city of Slonim (2 March) and crossed the Neman, whilst Lithuanian advances forced the Soviets out of Panevėžys. A final Soviet counter-offensive retook Panevėžys and Grodno in early April, but the Western Army was too thinly spread to fight both the Polish and Lithuanian troops, and the German units assisting them. The Polish offensive quickly gained momentum, and Vilna offensive in April 1919, forced Litbel to evacuate the capital first to Dvinsk (28 April), then to Minsk (28 April), then to Bobruysk (19 May). As the Litbel lost territory, its powers were quickly stripped by Moscow. For example, on 1 June Vtsik's decree put all of Litbel's armed forces under the command of the Red Army. On 17 July, the Defence Soviet was liquidated, and its function was passed to Minsk's Milrevcom. When on 8 August Polish forces captured Minsk, that same day the capital was evacuated to Smolensk. On 28 August Lithuanian forces took Zarasai (the last Lithuanian town held by Litbel) and the same day Bobruysk fell to the Poles.

By late summer of 1919, the Polish advance was also exhausted. The defeat of the Red Army allowed the outbreak of another historic disagreement over territory between Poland and Lithuania; their competition to control the city of Vilnius soon erupted into a military conflict, with Poland winning. Facing Denikin and Kolchak, Soviet Russia could not spare men for the western front. A stalemate with localised skirmishes developed between Poland and Lithuania.

Pawn on a chessboard

The stalemate and the occasional (though fruitless) negotiations gave Russia a much needed pause to concentrate on other regions. During the latter half of 1919 the Red Army successfully defeated Denikin in the South, taking over the Don, North Caucasus and Eastern Ukraine, pushed Kolchak from the Volga, beyond the Ural mountains into Siberia. In autumn of 1919, Nikolai Yudenich's advance on Petrograd was checked, whilst in the far north the Evgeny Miller's army was pushed into the Arctic. On the diplomatic front, on 11 September 1919, the People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs of Soviet Russia, Georgy Chicherin, sent a note to Lithuania with a proposal for a peace treaty. It was a de facto recognition of the Lithuanian state.[12] Similar negotiations with Estonia and Latvia, gave way for a peace treaty with the former on 2 February 1920 and a cease-fire agreement with the latter a day earlier.

Having secured several frontiers and breaking the "Ring of Fronts" the Soviet government began building up its forces for the massive offensive westwards, bringing the World Revolution to Europe. However the Polish role of preventing this and creating a "buffer zone" at the expense of Belarus was not its sole goal. The new leader Józef Piłsudski rallied the Poles under a nationalist rhetoric to re-create the historic Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Międzymorze, which would include Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus and push the eastern border as far as possible into Russia.

War continues

In April 1920, Poland initiated its major offensive. However the Soviet Red Army was much more organised than it was a year earlier, and though Polish troops managed to make several gains in Ukraine, notably the capture of Kiev, in Byelorussia, both of its offensives towards Zhlobin and Orsha were thrown back in May.

In June, the RSFSR was finally ready to open its major Western advance. To preserve the neutrality of Lithuania (though the peace treaty was still being negotiated), on 6 June the exiled government of Litbel was disbanded. Within a few days, the 3rd Cavalry Corps under command of Hayk Bzhishkyan broke the Polish front, causing a collapse and a retreat. On 11 July Minsk was re-taken, and on 31 July 1920 once again the Soviet Socialist Republic of Belorussia was re-established in Minsk.

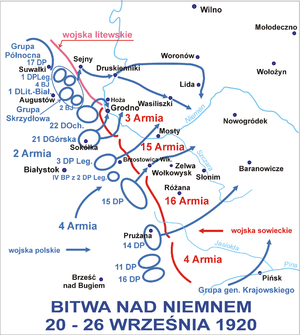

As the front moved west, and more Belarusian lands were adjoined to the new republic, the first administrative decrees were issued. The entity was divided into seven uyezds: Bobruysk, Borisov, Igumen, Minsk, Mozyr and Slutsk. (Vitebsk, Gomel and Mogilev remained part of the RSFSR.) This time the leaders were Aleksandr Chervyakov (head of Minsk's milrevcom) and Wilhelm Knorin (as chairmen of the Central Committee of the Belarusian Communist Party). The SSRB sought to join further territories, as the Red Army crossed into Poland, but the decisive Polish victory at the Battle of Warsaw in August ended these ambitions. Once again, the Red Army found itself on the defensive in Belorussia. The Poles were able to successfully break the Russian lines at the Battle of the Niemen River in September 1920. As a result, the Soviets were not only forced to abandon their World Revolution targets, but Western Belarus too. However early autumn rains halted the Polish advance, which exhausted itself by October. A cease-fire agreed on 12 October, came into effect on 18 October.

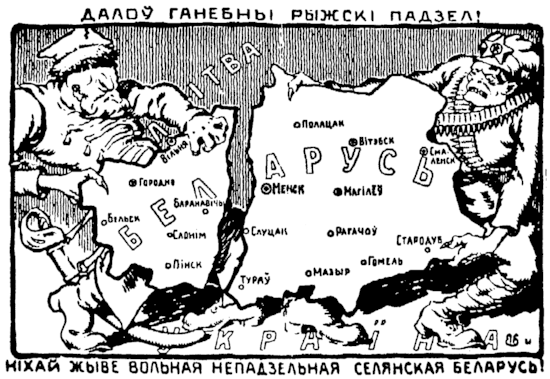

Slutsk uprising

As the negotiations between the Polish Republic and the Russian Bolshevik government took place in Riga, the Soviet side saw the armistice as only a temporary setback in its western advance. Seeing the failure of overcoming the Polish nationalist rhetoric with Communist propaganda, the Soviet government chose a different tactic, by appealing to the minorities of the Polish state, creating a fifth column element out of Belarusians and Ukrainians. During the negotiations, RSFSR offered all of BSSR to Poland in return for concessions in Ukraine, which were rejected by the Polish side. Eventually a compromising armistice line was agreed, which would see the Belarusian city of Slutsk handed over to the Bolsheviks.

News of Belarus' upcoming permanent division angered the population, and using the town's Polish occupation, the local population began self-organising into a militia and associating itself with the Belarusian Democratic Republic. On 24 November the Polish units left the town, and for nearly a month the Slutsk partisans resisted Soviet attempts to re-gain control of the area. Eventually the Red Army had to mobilise two divisions to overcome the resistance, when the last units of Slutsk militia crossed the Moroch River and interned by the Polish border guards.

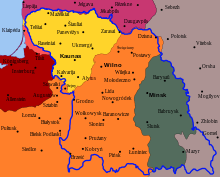

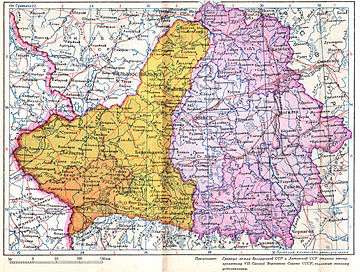

Early-Soviet years

In February 1921, the delegations of the Second Polish Republic and the Russian SFSR finally signed the Treaty of Riga putting an end of hostilities in Europe, and Belarus in particular. Six years of war had left the land neglected and looted, and the endless change of occupying regimes, each worse than the previous left their mark on the Belarusian people, who were now divided. Almost half (Western Belarus) now belonged to Poland, Eastern Belarus (Gomel, Vitebsk and parts of Smolensk guberniyas) were administered by the RSFSR. The rest was the SSRB, a republic with 52,400 square kilometres and a population of a mere 1.544 million people.

An interesting paradox arose in the status of SSRB within the future Bolshevik state. On one hand its small geographic, population and almost negligent economic indicators did not warrant it much political weight on Soviet affairs. In fact the leader of the Communist Party of Byelorussia (Bolshevik), Alexander Chervyakov would represent Byelorussian communists at seven party congresses in Moscow, but not once be elected into the party's Central Committee. Moreover, the weak national sentiment of the Belarusian people would easily have allowed SSRB to be disbanded and annexed to the RSFSR, unlike for example Ukraine.

On the other hand, the region's strategic role decided its fate, as a full Union republic within the negotiations upon forming the future state. For one Leon Trotsky and his supporters within the Soviet leadership still supported its World Revolution concept, and as said above, viewed the Treaty of Riga as only a temporary setback to the process, and a future advance would require a prepared bridgehead. This justified giving the SSRB the status of a full union republic within the Treaty on the Creation of the USSR that was signed on 30 December 1922. SSR Byelorussia became a founding member of the Soviet Union in 1922 and became known as BSSR.[13]

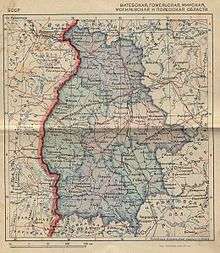

However the politics in Moscow took a different course of events, and eventually the accession of Joseph Stalin saw a new policy adapted Socialism in One Country. In accordance to which, expansionist and irredentist claims were removed from Soviet ideology, which instead would focus on making regions economically viable. Thus on March 1924, by decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, Russia returned most of territories that made up the Vitebsk and Mogilev Governorates, as well as parts of Smolensk. The passing of land that largely survived the destruction of war not only doubled the SSRB's area to 110,600 square kilometres, but also raised the population to 4.2 million people.

SSRB in the mid-1920s

According to its entry in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia,[14] in 1925 SSRB was a largely rural country. Out of the 4,342,800 people that inhabited it, only 14.5% lived in urban areas. Administratively it was split into ten okrugs: Bobruysk, Borisov, Vitebsk, Kalinin, Minsk, Mogilev, Mozyr, Orsha, Polotsk, and Slutsk; all of which contained a total of 100 raions and 1,229 selsoviets. Only 25 towns and cities and an additional 49 urban settlements.

Trotsky's plan for the SSRB to act as a future magnet for the minorities in the Second Polish Republic is clearly evidenced in the national policies. The republic initially had four official languages: Belarusian, Russian, Yiddish, and Polish, despite the fact that the Russians and the Poles made up only around 2% of the total population (most of the later lived next to the state border in the Minsk and Borisov districts). The most important minority was the Jewish population of Belarus, which had a long history of targeted oppression under the Tsars, and in 1925 made up almost 44% of the urban population and began to be aided by affirmative action programmes. In 1924 the government created a committee – Belkomzet – to allocate land to Jewish families, in 1926 a total of 32,700 hectares were given for 6,860 Jewish families. Jews would continue to play a major role in Byelorussian politics, society and economy right up to the Second World War, in fact between 1928 and 1930 the First secretary of the Communist Party of Byelorussia, was Yakov Gamarnik, a Jew.

Yet, the titular nation of the SSRB were the Belarusians, which made up 82% of the rural population, but less than half of the urban one (40.1%). The Belarusian national sentiment was a lot weaker than that of neighbouring Ukraine, this was greatly exploited by the Bolshevik-Polish power struggle in the Polish–Soviet War. (In fact to avoid being annexed to Poland, at the census of 1920, many chose to be label themselves as Russians.[14]). To appeal to the Belarusians of Western Belarus and also to prevent the nationalist element of the exiled Belarusian Democratic Republic from having any influence on the population (i.e. to avoid another Slutsk uprising), a policy of Korenizatsiya was widely implemented. Belarusian language, folklore and culture was put at front of everything else. This went on par with the Soviet policy of liquidation of illiteracy (likbez).

Economically the republic remained largely self-centred, and most of the effort was put into restoring and repairing the war-damaged industry (if in 1923 there was only 226 different fabrics and factories, then by 1926 the number climbed to 246, however the employed manpower jumped from 14 thousand to 21.3 thousand workers). The majority was food industry followed by metal and wood working combines. A lot more was centred in local and private sector, as allowed by the New Economic Policy of the USSR, in 1925 these number 38.5 thousand who employed almost 50 thousand people. Most being textile workshops and lumber yards and blacksmiths.

To further make the republic prosperous and to continue the creating of well-defined national territorial units. On 6 December 1926 the SSRB was once again enlarged by passing parts of RSFSR's Gomel Governorate, which included the cities of Gomel and Rechytsa. This increased the area to 126,300 square kilometres and the 1926 Soviet census that was held at the same time reported a population of 4,982,623. Of the latter 83% was rural, and Belarusians made up 80.6% (though only 39.2% of urban, yet 89% of rural).

On 11 April 1927, the republic adopted its new Constitution, bringing its laws in tie with those of the USSR and changing the name from the Soviet Socialist Republic of Byelorussia to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. The head of government (chairman of the Soviet of People's Commissars) was taken up Nikolay Goloded, whilst Vilhelm Knorin remained the first secretary of the Communist Party.

Stalinist years

The 1930s marked the peak of Soviet repressions in Belarus. According to incomplete calculations, about 600,000 people fell victim to Soviet repressions in Belarus between 1917 and 1953.[15][16] Other estimates put the number at higher than 1.4 million persons.,[17] of which 250,000 were sentenced by judicial or executed by extrajudicial bodies (dvoikas, troikas, special commissions of the OGPU, NKVD, MGB). Excluding those sentenced in the 1920s–1930s, over 250,000 Belarusians were deported as kulaks or kulak family members in regions outside the Belarusian Soviet Republic. The scale of Soviet terror in Belarus was higher than in Russia or Ukraine which resulted in a much stronger extent of Russification in the republic.

A Polish Autonomous District was founded in 1932 and disbanded in 1935.

In September 1939, the Soviet Union, following the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany, occupied eastern Poland after the 1939 invasion of Poland. The former Polish territories referred to as West Belarus were incorporated into the Belarusian SSR, with an exception of the city of Vilnius and its surroundings that were transferred to Lithuania. The annexation was internationally recognized after the end of World War II.

Occupation of Belarus by Nazi Germany

_06.jpg)

In the summer of 1941, Belarus was occupied by Nazi Germany. A large part of the territory of Belarus became the General District Belarus within the Reichskommissariat Ostland.

Nazi Germany imposed a brutal regime, deporting some 380,000 people for slave labour, and killing hundreds of thousands of civilians more. At least 5,295 Belarusian settlements were destroyed by the Germans and some or all their inhabitants killed (out of 9,200 settlements that were burned or otherwise destroyed in Belarus during World War II).[18] More than 600 villages like Khatyn were annihilated with their entire population.[18] Altogether, over 2,000,000 people were killed in Belarus during the three years of German occupation, almost a quarter of the region's population.[19][20]

After World War II, the Byelorussian SSR was given a seat in the United Nations General Assembly together with the Soviet Union and Ukrainian SSR, becoming one of the founding members of the UN. This was part of a deal with the United States to ensure a degree of balance in the General Assembly, which, the USSR opined, was unbalanced in favor of the Western Bloc. A Byelorussian, G.G. Chernushchenko, served as President of the United Nations Security Council from January–February 1975.

Dissolution

.svg.png)

In its last years during perestroika under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Supreme Soviet of Byelorussian SSR declared sovereignty on 27 July 1990 over Soviet laws.

Following the failed coup in August, the republic declared independence from the Soviet Union on 25 August 1991. The republic was renamed the Republic of Belarus on 19 September 1991. On 8 December 1991 it was a signatory, along with Russia and Ukraine, of the Belavezha Accords, which replaced the Soviet Union with the Commonwealth of Independent States. Belarus received independence on 25 December 1991. A day later the Soviet Union ceased to exist. However, the Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Republic of Belarus of 1978, was retained after independence.

Politics and government

Byelorussia was a one-party socialist republic, governed by the Communist Party of Byelorussia, a branch within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU/KPSS). Like all other Soviet republics, it was one of the 15 constituent republics composing the Soviet Union from its entry into the union in 1922 till its dissolution in 1991. Executive power was exercised by the Byelorussian Communist Party authorities, at its top sits the Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Legislative power was vested in the unicameral parliament, the Supreme Soviet of Byelorussia, also dominated by the Communist Party.

Belarus is the legal successor of the Byelorussian SSR and in its Constitution it states, "Laws, decrees and other acts which were applied in the territory of the Republic of Belarus prior to the entry into force of the present Constitution shall apply in the particular parts thereof that are not contrary to the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus."[21]

Foreign relations

On the international stage, Byelorussia (along with Ukraine) was one of only two republics to be separate members of the United Nations. Both republics and the Soviet Union joined the UN when the organization was founded with the other 50 states on 24 October 1945. In effect, this provided the Soviet Union (a permanent Security Council member with veto powers) with another 2 votes in the General Assembly.

Apart from the UN, the Byelorussian SSR was a member of the UN Economic and Social Council, UNICEF, International Labour Organization, Universal Postal Union, World Health Organization, UNESCO, International Telecommunication Union, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, World Intellectual Property Organization and the International Atomic Energy Agency. Byelorussia was excluded separately from the Warsaw Pact, Comecon, the World Federation of Trade Unions and the World Federation of Democratic Youth. In 1949, it joined the International Olympic Committee as a Union Republic.

Demographics

According to the 1959 Soviet Census, the population of the republic were made up as follows:

Ethnicities (1959):

- Belarusians – 81%

- Poles – 16%

- Lithuanians – 5%

- Ukrainians – about 1%

- Jews – about 1%

- Russians – <1%

The largest cities were:

Culture

Cuisine

Whilst part of the Union, the cuisine of Byelorussia consisted mainly of vegetables, meat (particularly pork), and bread. Foods are usually either slowly cooked or stewed. Typically, Byelorussians eat a light breakfast and two hearty meals, with dinner being the largest meal of the day. Wheat and rye breads are consumed in Belarus, but rye is more plentiful because conditions are too harsh for growing wheat. Many of the cuisines within Byelorussia also shared its cuisine with its Russian neighbour.

See also

References and notes

- In interwar Soviet Belarus, between 1924 and 1938, four languages were official, namely, Belarusian, Polish, Russian and Yiddish. See: Кожинова, Алла Андреевна (2017). "Языки и графические системы Беларуси в периодот Октябрьской революции до Второй мировой войны". Studi Slavistici. 14: 133–156.

- Some parts, e.g., Švenčionys, Šalčininkai, Dieveniškės, Adutiškis, Druskininkai, were annexed in 1939 from Poland to Byelorussia, but passed to Lithuania in 1940

- L. N. Drobaŭ (1971). Art of Soviet Byelorussia. Avrora.

- Zaprudnik, Jan (1993). Belarus: At A Crossroads In History. Westview Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-8133-1794-0.

- Язэп Юхо (Joseph Juho) (1956) Аб паходжанні назваў Белая і Чорная Русь (About the Origins of the Names of White and Black Ruthenia).

- Philip G. Roeder (15 December 2011). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. ISBN 978-0-691-13467-3.

- Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1.

- Richmond, Yale (1995). From Da to Yes: Understanding the East Europeans. Intercultural Press. p. 260. ISBN 1-877864-30-7.

- Ioffe, Grigory (25 February 2008). Understanding Belarus and How Western Foreign Policy Misses the Mark. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 41. ISBN 0-7425-5558-5.

- Andrew Ryder (1998). Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, Volume 4. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 1-85743-058-1.

- Čepėnas, Pranas (1986). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). II. Chicago: Dr. Griniaus fondas. p. 315. ISBN 5-89957-012-1.

- Čepėnas, Pranas (1986). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). II. Chicago: Dr. Griniaus fondas. pp. 355–359. ISBN 5-89957-012-1.

- In Soviet historiography the term "SSRB" was suppressed, but there is documentary evidence of the usage of the term SSRB rather than BSSR, see, e.g., A 1992 cancellation of a 1921 SSRB laws

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia 1st edition, Volume 5, p.378-413, 1927

- В. Ф. Кушнер. Грамадска-палітычнае жыццё ў БССР у 1920—1930–я гг. Гісторыя Беларусі (у кантэксьце сусьветных цывілізацыяў) p. 370.

- 600 000 ахвяраў — прыблізная лічба Archived 11 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine: з І. Кузьняцовым гутарыць Руслан Равяка // Наша Ніва, 3 кастрычніка 1999.

- Ігар Кузьняцоў. Рэпрэсіі супраць беларускай iнтэлiгенцыi і сялянства ў 1930—1940 гады. Лекцыя 2. Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine // «Беларускі Калегіюм», 15 чэрвеня 2008.

- (in English) "Genocide policy". Khatyn.by. SMC "Khatyn". 2005.

- Vitali Silitski (May 2005). "Belarus: A Partisan Reality Show" (PDF). Transitions Online: 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2006.

- "The tragedy of Khatyn - Genocide policy". SMC Khatyn. 2005.

- Constitution of Belarus, Art. 142.

Further reading

- Baranova, Olga. "Nationalism, anti-Bolshevism or the will to survive? Collaboration in Belarus under the Nazi occupation of 1941–1944." European Review of History—Revue européenne d'histoire 15.2 (2008): 113-128.

- Bekus, Nelly. Struggle over Identity: The Official and the Alternative “Belarussianness” (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2010);

- Bemporad, Elissa. Becoming Soviet Jews: The Bolshevik Experiment in Minsk (Indiana UP, 2013).

- Epstein, Barbara. The Minsk Ghetto 1941-1943: Jewish Resistance and Soviet Internationalism (U of California Press, 2008).

- Guthier, Steven L. "The Belorussians: National identification and assimilation, 1897–1970: Part 1, 1897–1939." Soviet Studies 29.1 (1977): 37-61.

- Horak, Stephan M. "Belorussia: Modernization, Human Rights, Nationalism." Canadian Slavonic Papers 16.3 (1974): 403-423.

- Lubachko, Ivan S. Belorussia: Under Soviet Rule, 1917--1957 (U Press of Kentucky, 2015).

- Marples, David R. "Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia Under Soviet Occupation: The Development of Socialist Farming, 1939-1941." Canadian Slavonic Papers' 27.2 (1985): 158- 177. online

- Marples, David. 'Our Glorious Past': Lukashenka's Belarus and the Great Patriotic War (Columbia University Press, 2014)

- Olson, James Stuart; Pappas, Lee Brigance; Pappas, Nicholas C.J. (1994). Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27497-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plokhy, Serhii (2001). The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924739-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richmond, Yale (1995). From Da to Yes: Understanding the East Europeans. Intercultural Press. ISBN 1-877864-30-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rudling, Pers Anders. The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906–1931 (University of Pittsburgh Press; 2014) 436pp online review

- Silitski, Vitali & Jan Zaprudnik (2010). The A to Z of Belarus. Scarecrow Press.

- Smilovitsky, Leonid. "Righteous Gentiles, the Partisans, and Jewish Survival in Belorussia, 1941–1944." Holocaust and Genocide Studies 11.3 (1997): 301-329.

- Snyder, Timothy. (2004) The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999 excerpt and text search

- Szporluk, Roman. "West Ukraine and West Belorussia: Historical tradition, social communication, and linguistic assimilation." Soviet Studies 31.1 (1979): 76-98. online

- Szporluk, Roman. "The press in Belorussia, 1955–65." Europe‐Asia Studies 18.4 (1967): 482-493.

- Urban, Michael E. An Algebra of Soviet Power: Elite Circulation in the Belorussian Republic 1966-86 (Cambridge UP, 1989).

- Vakar, Nicholas Platonovich. Belorussia: the making of a nation: a case study (Harvard UP, 1956).

- Vakar, Nicholas Platonovich. A bibliographical guide to Belorussia (Harvard UP, 1956).

- Wexler, Paul. "Belorussification, Russification and Polonization Trends in the Belorussian Language 1890-1982." in Kreindler, ed., Sociolinguistic Perspectives (1985): 37-56.

- Zaprudnik, Jan (1993). Belarus: At A Crossroads In History. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-1794-0. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zejmis, Jakub. "Belarus in the 1920s: Ambiguities of national formation." Nationalities Papers 25.2 (1997): 243-254.

External links

- Byelorussia : speeding towards abundance by Tikhon Kiselev.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)