Polonization

Polonization (or Polonisation; Polish: polonizacja)[1] is the acquisition or imposition of elements of Polish culture, in particular the Polish language. This was experienced in some historic periods by the non-Polish populations of territories controlled or substantially under the influence of Poland. With other examples of cultural assimilation, it could either be voluntary or forced and is most visible in the case of territories where the Polish language or culture were dominant or where their adoption could result in increased prestige or social status, as was the case of the nobility of Ruthenia and Lithuania. To a certain extent Polonization was also administratively promoted by the authorities, particularly in the period following World War II.

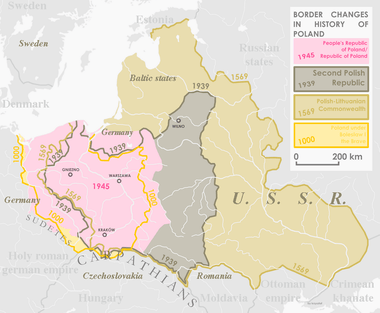

Poland's and the Commonwealth's historical borders | |

| Duration | 1569–1945 |

|---|---|

| Location | Poland throughout history |

| Borders | Yellow – 1000 Khaki – 1569 Silver – 1939 Pink – 1945 |

Summary

Polonization can be seen as an example of cultural assimilation. Such a view is widely considered applicable to the times of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795) when the Ruthenian and Lithuanian upper classes were drawn towards the more Westernized Polish culture and the political and financial benefits of such a transition, as well as, sometimes, by the administrative pressure exerted on their own cultural institutions, primarily the Orthodox Church. Conversion to the Roman Catholic (and to a lesser extent, Protestant) faith was often the single most important part of the process. For Ruthenians of that time, being Polish culturally and Roman Catholic by religion was almost the same. This diminishing of the Orthodox Church was the part most resented by the Belarusian and Ukrainian masses. In contrast the Lithuanians, who were mostly Catholic, were in danger of losing their cultural identity as a nation, but that was not realised by the wide masses of Lithuanians until the Lithuanian national renaissance in the middle of the 19th century.

On the other hand, the Polonization policies of the Polish government in the interwar years of the 20th century were again twofold. Some of them were similar to the mostly forcible assimilationist policies implemented by other European powers that have aspired to regional dominance (e.g., Germanization, Russification), while others resembled policies carried out by countries aiming at increasing the role of their native language and culture in their own societies (e.g., Magyarization, Rumanization, Ukrainization). For Poles, it was a process of rebuilding Polish national identity and reclaiming Polish heritage, including the fields of education, religion, infrastructure and administration, that suffered under the prolonged foreign occupation by the neighboring empires of Russia, Prussia, and Austria-Hungary. However, as a third of recreated Poland's population was ethnically non-Polish and many felt their own nationhood aspirations thwarted specifically by Poland, large segments of this population resisted to varying extents the policies intended to assimilate them. Part of the country's leadership emphasized the need for the ethnic and cultural homogeneity of the state in the long term. However, the promotion of the Polish language in administration, public life and especially education, were perceived by some as an attempt at forcible homogenization. In areas inhabited by ethnic Ukrainians for example, actions of the Polish authorities seen as aiming at restricting the influence of the Orthodox and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church caused additional resentment, and were considered to be closely tied to religious Polonization.

12th–16th centuries

Between the 12th and the 14th centuries many towns in Poland adopted the so-called Magdeburg rights that promoted the towns' development and trade. The rights were usually granted by the king on the occasion of the arrival of migrants. Some, integrated with the larger community, such as merchants who settled there, especially Greeks and Armenians. They adopted most aspects of Polish culture but kept their Orthodox faith. Since the Middle Ages, Polish culture, influenced by the West, in turn radiated East, beginning the long process of cultural assimilation.[2]

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795)

In the 1569 Union of Lublin, the Ruthenian territories controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were transferred to the newly formed Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[3] The non-Polish ethnic groups found themselves under strong influence of the Polish culture and language.[4][5][6] Quarter century later, following the Union of Brest the Ruthenian Church sought to break relations with the Eastern Orthodox Church.[7] The sparsely populated lands,[8] owned by the Polish and Polonized nobility,[7] were settled by farmers from central Poland.[8][9][10][7] The attractions,[11]:11[12] and pressures of Polonization on Ruthenian nobility and cultural elite resulted in almost complete abandonment of Ruthenian culture, traditions and the Orthodox Church by the Ruthenian higher class.[13]

The Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila was offered the Polish crown and became Władysław II Jagiełło (reigned 1386–1434). This marked the beginning of the gradual, voluntary Polonization of the Lithuanian nobility.[14][15][16] Jagiełło built many churches in pagan Lithuanian land and provided them generously with estates, gave out the lands and positions to the Catholics, settled the cities and villages and granted the biggest cities and towns Magdeburg Rights. The Ruthenian nobility was also freed from many payment obligations and their rights were equalized with those of the Polish nobility.

Under Jogaila successor as a king of Crown Władysław III of Varna, who reigned in 1434–1444, Polonization attained a certain degree of subtlety. Władysław III introduced some liberal reforms. He expanded the privileges to all Ruthenian nobles irrespective of their religion, and in 1443 signed a bull equalizing the Orthodox church in rights with the Roman Catholicism thus alleviating the relationship with the Orthodox clergy. These policies continued under the next king Casimir IV Jagiellon. Still, the mostly cultural expansion of the Polish influence continued since the Ruthenian nobility were attracted by both the glamour of the Western culture and the Polish political order where the magnates became the unrestricted rulers of the lands and serfs in their vast estates.[17]

Some Ruthenian magnates like Sanguszko, Wiśniowiecki and Kisiel, resisted the cultural Polonization for several generations, with the Ostrogski family being one of the most prominent examples. Remaining generally loyal to the Polish state, the magnates, like Ostrogskis, stood by the religion of their forefathers, and supported the Orthodox Church generously by opening schools, printing books in Ruthenian language (the first four printed Cyrillic books in the world were published in Cracow, in 1491[18]) and giving generously to the Orthodox churches' construction. However, their resistance was gradually waning with each subsequent generation as more and more of the Ruthenian elite turned towards Polish language and Catholicism. Still, with most of the educational system getting Polonized and the most generously funded institutions being to the west of Ruthenia, the Ruthenian indigenous culture further deteriorated. In the Polish Ruthenia the language of the administrative paperwork started to gradually shift towards Polish. By the 16th century the language of administrative paperwork in Ruthenia was a peculiar mix of the older Church Slavonic with the Ruthenian language of the commoners and the Polish language. With the Polish influence in the mix gradually increasing it soon became mostly like the Polish language superimposed on the Ruthenian phonetics. The total confluence of Ruthenia and Poland was seen coming.[19]

As the Eastern Rite Greek-Catholic Church originally created to accommodate the Ruthenian, initially Orthodox, nobility, ended up unnecessary to them as they converted directly into the Latin Rite Catholicism en masse, the Church largely became an hierarchy without followers. The Greek Catholic Church was then used as a tool aimed to split even the peasantry from their Ruthenian roots, still mostly unsuccessfully.[7] The commoners, deprived of their native protectors, sought protection through the Cossacks,[7] who, being fiercely Orthodox, tended also to easily turn to violence against those they perceived as their enemies, particularly the Polish state and what they saw as its representatives, the Poles and generally the Catholics, as well as the Jews.[19]

After several Cossack uprisings, especially the fateful Khmelnytsky uprising, and foreign invasions (like the Deluge), the Commonwealth, increasingly powerless and falling under the control of its neighbours,[20][21] started to decline, the process which eventually culminated with the partitions of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the end of the 18th century and no Polish statehood for the next 123 years.

While the Commonwealth's Warsaw Compact is widely considered an example of an unprecedented religious tolerance for its time,[22] the oppressive policies of Poland towards its Eastern Orthodox subjects is often cited as one of the main reasons that brought the state's demise.[23]

During all time of existing of Commonwealth Polonization in western part of country referred to rather small groups of colonists, like Bambrzy in Greater Poland.

Partitions (1795–1918)

Polonization also occurred during times when a Polish state didn't exist, despite the empires that partition Poland applied the policies aimed at reversing the past gains of Polonization or aimed at replacing Polish identity and eradication of Polish national group.[24][25][26][27]

The Polonization took place in the early years of the Prussian partition, where, as a reaction to the persecution of Roman Catholicism during the Kulturkampf, German Catholics living in areas with a Polish majority voluntarily integrated themselves within Polish society, affecting approximately 100,000 Germans in the eastern provinces of Prussia.[24]

According to some scholars the biggest successes in Polonization of the non-Polish lands of former Commonwealth were achieved after the Partitions, in times of persecution of Polishness (noted by Leon Wasilewski (1917[28]), Mitrofan Dovnar-Zapolsky (1926[29])). Paradoxically, the substantial eastward movement of the Polish ethnic territory (over these lands) and growth of the Polish ethnic regions were taking place exactly in the period of the strongest Russian attack on everything Polish in Lithuania and Belarus.[30]

The general outline of causes for that is considered to include the activities of the Roman-Catholic Church[31] and the cultural influence exacted by the big cities (Vilna, Kovno) on these lands,[32] the activities of the Vilna educational district in 19th century–1820s,[33] the activities of the local administration, still controlled by the local Polish or already Polonized nobility up to the 1863–1864 January uprising,[34] secret (Polish) schools in second half nineteenth to the beginning of the 20th century (tajne komplety)[34] and the influence of the land estates.[34]

Following the demise of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the end of the 18th century, the Polonization trends initially continued in Lithuania, Belarus and Polish-dominated parts of Ukraine as the initially liberal policies of the Empire gave the Polish elite significant concessions in the local affairs. Dovnar-Zapolsky notes[35] that the Polonization actually intensified under the liberal rule of Alexander I, particularly due to the efforts of Polish intellectuals who led the Vilnius University which was organized in 1802–1803 from the Academy in Vilna (Schola Princeps Vilnensis), vastly expanded and given the highest Imperial status under the new name Vilna Imperial University (Imperatoria Universitas Vilnensis).[36] By the Emperor's order, the Vilna education district overseen by Adam Czartoryski, a personal friend of Alexander, was greatly expanded to include the vast territories in the West of the Russian Empire stretching to Kiev in south-east and much of the Polish territory and the development of the University, which had no rival in the whole district, received the highest priority of the Imperial authorities which granted it significant freedom and autonomy.[36] With the effort of Polish intellectuals who served the rectors of the University, Hieronim Strojnowski, Jan Śniadecki, Szymon Malewski, as well as Czartoryski who oversaw them, the University became the center of Polish patriotism and culture; and as the only University of the district the center attracted the young nobility of all ethnicities from this extensive region.[36][37]

With time, the traditional Latin was fully eliminated from the University and by 1816 it was fully replaced by Polish and Russian. This change both affected and reflected a profound change in the Belarusian and Lithuanian secondary schools systems where Latin was also traditionally used as the University was the main source of the teachers for these schools. Additionally, the University was responsible for the textbooks selection and only Polish textbooks were approved for printing and usage.[37]

Dovnar-Zapolsky notes that "the 1800s–1810s had seen the unprecedented prosperity of the Polish culture and language in the former Great Duchy of Lithuania lands" and "this era has seen the effective completion of the Polonization of the smallest nobility, with further reduction of the areal of use of the contemporary Belarusian language.[38] also noting that the Polonization trend had been complemented with the (covert) anti-Russian and anti-Eastern Orthodox trends.[39] The results of these trends are best reflected in the ethnic censuses in previously non-Polish territories.

Following the Polish November uprising aimed at breaking away from Russia, the Imperial policies finally changed abruptly. The University was forcibly closed in 1832 and the following years where characterized by the policies aimed at the assimilationist solution of the "Polish question", a trend that was further strengthened following another unsuccessful uprising (1863).

In the 19th century, the mostly unchallenged Polonization trend of the previous centuries had been met staunchly by then "anti-Polish" Russification policy, with temporary successes on both sides, like Polonization rises in mid-1850s and in 1880s and Russification strengthenings in 1830s and in 1860s.[40] Any Polonization of the east and west territories (Russian and German partitions) occurred in the situation were Poles had steadily diminishing influence on the government. Partition of Poland posed a genuine threat to the continuation of Polish language-culture in those regions.[26] As Polonization was centered around Polish culture, policies aimed at weakening and destroying it had a significant impact on weakening Polonization of those regions. This was particularly visible in Russian-occupied Poland, where the Polish culture fared worst, as Russian administration gradually became strongly anti-Polish.[26] After a brief and relatively liberal early period in the early 19th century, where Poland was allowed to retain some autonomy as the Congress Poland puppet state,[41] the situation for Polish culture steadily worsened.

Second Polish Republic (1918–1939)

By the times of Second Polish Republic (1918–1939) much of Poland's previous territory, which were historically mixed Ruthenian and Polish, had Ukrainian and Belorussian majorities.[42] Following the post-World War I rebirth of the Polish statehood, these lands again became disputed but the Poles were more successful than the nascent West Ukrainian People's Republic in the Polish-Ukrainian War of 1918. Approximately one third of the new state's population was non-Catholic,[43] including a large number of Russian Jews who immigrated to Poland following a wave of Ukrainian pogroms which continued until 1921.[44] The Jews were entitled by a peace treaty in Riga to choose the country they preferred and several hundred thousand joined the already large Jewish minority of the Polish Second Republic.[45]

The issue of non-Polish minorities was a subject of intense debate within the Polish leadership. Two ideas of Polish policy clashed at the time: a more tolerant and less assimilationist approach advocated by Józef Piłsudski,[46] and an assimilationist approach advocated by Roman Dmowski and Stanisław Grabski.

Linguistic assimilation was considered by National Democrats to be a major factor for "unifying the state." For example, Grabski as Polish Minister for Religion and Public Education in 1923 and 1925–1926, wrote that "Poland may be preserved only as a state of Polish people. If it were a state of Poles, Jews, Germans, Rusyns, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Russians, it would lose its independence again"; and that "it is impossible to make a nation out of those who have no 'national self-identification,' who call themselves 'local' (tutejszy)." Grabski also said that "the transformation of the state territory of the Republic into a Polish national territory is a necessary condition of maintaining our frontiers."[47]

In internal politics, Piłsudski's reign marked a much-needed stabilization and improvement in the situation of ethnic minorities, which formed almost a third of the population of the Second Republic. Piłsudski replaced the National-Democratic "ethnic-assimilation" with a "state-assimilation" policy: citizens were judged by their loyalty to the state, not by their ethnicity.[48] The years 1926–1935 were favourably viewed by many Polish Jews, whose situation improved especially under the cabinet of Piłsudski's appointee Kazimierz Bartel.[49] However a combination of various reasons, from the Great Depression,[48] through the Piłsudski's need for support from parties for the parliament's election[48] to the vicious spiral of terrorist attacks by Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and government pacifications[48][50] meant that the situation continued to degenerate, despite Piłsudski's efforts.

However, Polonization also created a new educated class among the non-Polish minorities, a class of intellectuals aware of the importance of schooling, press, literature and theatre, who became instrumental in the development of their own ethnic identities.[51]

Polonization in Eastern Borderlands (Kresy)

The territories of Western Belarus, western Ukraine and the Vilnius region, were incorporated into interwar Poland in 1921 at the Treaty of Riga in which the Polish eastern frontiers had been first defined following the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1921. At the same time, the government of the new Polish state, with pressure from the Allies agreed to grant political autonomy to Galicia, but not Volhynia.[48]

West Belarus

The Treaty of Riga signed between sovereign Poland and the Soviet Russia representing the Soviet Ukraine without any participation from Belarusian side assigned almost half of the modern-day Belarus (the western half of Soviet Belarus) to the Polish Second Republic. The government of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic according to the text of the Riga treaty was also acting "on behalf of Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic" formed in the course of war.[52] Additionally, in accordance with the Treaty, the Soviet Russia received three regions from the newly formed Soviet Belarus, which were reassigned back by the Bolsheviks in 1924 and 1926.[53] Protests by the exiled government of the Belarusian Democratic Republic proclaimed in 1918 were ignored by Poland and the Soviets.

According to Per Anders Rudling, the Belarusian language was essentially pushed out of the schools in Polish West Belarus in violation of the Minorities' Treaty between Poland and the Western powers of 1919.[54] The Polish author Marek Wierzbicki brings this in connection with the fact that the first textbook of Belarusian grammar was written no earlier than 1918.[55]

Following the intentions of the majority of the Polish society,[56] the Polish government introduced harsh policies of polonization and assimilation of Belarusians in West Belarus.[57] The Polish official Leopold Skulski, an advocate of polonization policies, is being quoted as saying in the Sejm in late 1930s: "I assure you that in some ten years you won't be able to find a single [ethnic] Belarusian [in West Belarus]".[58][59][60]

Władysław Studnicki, an influential Polish official at the administration of the Kresy region, openly stated that Poland needed the Eastern regions as an object for colonization.[61]

There widespread cases of discrimination of the Belarusian language,[62] it was forbidden for usage in state institutions.[63]

Orthodox Christians also faced discrimination in interwar Poland.[63] This discrimination was also targeting assimilation of Eastern Orthodox Belarusians.[64] The Polish authorities were imposing Polish language in Orthodox church services and ceremonies,[64] initiated the creation of Polish Orthodox Societies in various parts of West Belarus (Slonim, Bielastok, Vaŭkavysk, Navahrudak).[64]

Belarusian Roman Catholic priests like Fr. Vincent Hadleŭski[64] who promoted Belarusian language in the church and Belarusian national awareness were also under serious pressure by the Polish regime and the leadership of the Catholic Church in Poland.[64] The Polish Catholic Church issued documents to priests prohibiting the usage of the Belarusian language rather than Polish language in Churches and Catholic Sunday Schools in West Belarus. A 1921 Warsaw-published instruction of the Polish Catholic Church criticized the priests introducing the Belarusian language in religious life: “They want to switch from the rich Polish language to a language that the people themselves call simple and shabby”.[65]

Before 1921, there were 514 Belarusian language schools in West Belarus.[66] In 1928, there were only 69 schools which was just 3% of all existing schools in West Belarus at that moment.[67] All of them were phased out by the Polish educational authorities by 1939.[68] The Polish officials openly prevented the creation of Belarusian schools and were imposing Polish language in school education in West Belarus.[69] The Polish officials often treated any Belarusian demanding schooling in Belarusian language as a Soviet spy and any Belarusian social activity as a product of a communist plot.[70]

The Belarusian civil society resisted polonization and mass closure of Belarusian schools. The Belarusian Schools Society (Belarusian: Таварыства беларускай школы), led by Branisłaŭ Taraškievič and other activists, was the main organization promoting education in Belarusian language in West Belarus in 1921–1937.

Resistance to polonization in West Belarus

Compared to the (larger) Ukrainian minority living in Poland, Belarusians were much less politically aware and active. Nevertheless, according to Belarusian historians, the policies by the Polish government against the population of West Belarus increasingly provoked protests[63] and armed resistance. In the 1920s, Belarusian partisan units arose in many areas of West Belarus, mostly unorganized but sometimes led by activists of Belarusian left wing parties.[63] In the spring of 1922, several thousands Belarusian partisans issued a demand to the Polish government to stop the violence, to liberate political prisoners and to grant autonomy to West Belarus.[63] Protests were held in various regions of West Belarus until mid 1930s.[63]

The largest Belarusian political organization, the Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union (or, the Hramada), which demanded a stop to the polonization and autonomy for West Belarus, grew more radicalized by the time. It received logistical help from the Soviet Union,[71] and financial aid from the Comintern.[72] By 1927 Hramada was controlled entirely by agents from Moscow.[71] It was banned by the Polish authorities,[71] and further opposition to the Polish government was met with state-imposed sanctions once the connection between Hramada and the more radical pro-Soviet Communist Party of Western Belarus was discovered.[71] The Polish policy was met with armed resistance.[73]

West Ukraine

Territories of Galicia and Volhynia had different backgrounds, different recent histories and different dominant religions. Until the First World War, Galicia with its large Ukrainian Greek Catholic population in the east (around Lwów), and Polish Roman Catholics in the west (around Kraków), was controlled by the Austrian Empire.[48] On the other hand, the Ukrainians of Volhynia, formerly of the Russian Empire (around Równe), were largely Orthodox by religion, and were influenced by strong Russophile trends.[48] Both "Polish officials and Ukrainian activists alike, distinguished between Galician and Volhynian Ukrainians" in their political aims.[48] There was a much stronger national self-perception among the Galician Ukrainians increasingly influenced by OUN (Ukrainian nationalists).

Religion

While the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), which functioned in communion with the Latin Rite Catholicism, could have hoped to receive a better treatment in Poland where the leadership saw Catholicism as one of the main tools to unify the nation – the Poles under Stanisław Grabski saw the restless Galician Ukrainians as less reliable than the Orthodox Volhynian Ukrainians,[48] seen as better candidates for gradual assimilation. That's why the Polish policy in Ukraine initially aimed at keeping Greek Catholic Galicians from further influencing Orthodox Volhynians by drawing the so-called "Sokalski line".[48]

Due to the region's history the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church attained a strong Ukrainian national character, and the Polish authorities sought to weaken it in various ways. In 1924, following a visit with the Ukrainian Catholic believers in North America and western Europe, the head of the UGCC was initially denied reentry to Lviv for a considerable amount of time. Polish priests led by their bishops began to undertake missionary work among Eastern Rite faithful, and the administrative restrictions were placed on the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.[74]

With respect to the Orthodox Ukrainian population in eastern Poland, the Polish government initially issued a decree defending the rights of the Orthodox minorities. In practice, this often failed, as the Catholics, also eager to strengthen their position, had official representation in the Sejm and the courts. Any accusation was strong enough for a particular church to be confiscated and handed over to the Roman Catholic Church. The goal of the two so called "revindication campaigns" was to deprive the Orthodox of those churches that had been Greek Catholic before Orthodoxy was imposed by the tsarist Russian government.[75][76] 190 Orthodox churches were destroyed, some of the destroyed churches were abandoned,[77] and 150 more were forcibly transformed into Roman Catholic (not Greek Catholic) churches.[78] Such actions were condemned by the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, who claimed that these acts would "destroy in the souls of our non-united Orthodox brothers the very thought of any possible reunion."[74]

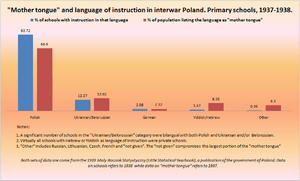

Education

The Polish administration closed many of the popular Prosvita Society reading rooms, an action which, combined with the devastation brought about during the war years, produced a marked decline in the number of reading rooms, from 2,879 in 1914 to only 843 in 1923.

As for the educational system, the provincial school administration from the Austrian era, which was based in L'viv and had separate Ukrainian representation, was abolished in January 1921. All decisions were subsequently to be made in Warsaw and to be implemented by administrators in local school districts. Ukrainians now found themselves within six different school districts (L'viv, Volhynia, Polissia, Cracow, Lublin, and Bialystok), although at least initially the Ukrainian school system, especially at the elementary level, was left undisturbed.[11]:588

In 1924, the government of Prime Minister Władysław Grabski passed a law (known as the lex Grabski), over the objections of Ukrainian parliamentary representatives, which set up bilingual Ukrainian and Polish schools. The result was a rapid decline in the number of unilingual Ukrainian schools together with a sharp increase in Polish-Ukrainian bilingual schools in Galicia and Polish schools in Volhynia (1,459 in 1938).[11]:594

Since Ukrainians in Poland had only limited control over the formal education of their children, the Plast scouting movement took up the challenge of inculcating youth with a Ukrainian national identity. Plast scouts came into being on the eve of World War I on Ukrainian lands in both the Russian and the Austro-Hungarian empires, but it was during the interwar years in western Ukraine (in particular Galicia and Transcarpathia) that they had their greatest success. By 1930, the organization had over 6,000 male and female members in branches affiliated with secondary schools in Galicia and with Prosvita societies in western Volhynia. Concerned by Plast's general popularity and the fact that many of its 'graduates' after age eighteen joined clandestine Ukrainian nationalist organizations, Poland's authorities increased restrictions on the movement until banning it entirely after 1930. It nonetheless continued to operate underground or through other organizations for the rest of the decade.

The principle of "numerus clausus" had been introduced following which the Ukrainians were discriminated when entering the Lviv University (not more than 15% of the applicants' total number, the Poles enjoying not less than the 50% quota at the same time).[79]

Land reform

The land reform designed to favour the Poles in Volhynia,[80] where the land question was especially severe, and brought the alienation from the Polish state of even the Orthodox Volhynian population who tended to be much less radical than the Greek Catholic Galicians.[48]

Traditionally, Volhynian Ukrainian peasants had benefited from rights of use in the commons, which in Volhynia meant the right to collect wood from forests owned by nobles. When all land was treated as private property with defined owners, such traditional rights could not be enforced. Forests were cleared, and the lumber sold abroad. Volhynian peasants lost access to what had been a common good, without profiting from its commercialization and sale.[81]

By 1938 nearly two million acres (some 800,000 hectares) had been redistributed within Ukrainian-inhabited areas. The redistribution did not necessarily help the local Ukrainian population, however. For instance, as early as 1920, 39 percent of the newly allotted land in Volhynia and Polissia (771,000 acres [312,000 hectares]) had been awarded as political patronage to veterans of Poland's 'war for independence,' and in eastern Galicia much land (494,000 acres [200,000 hectares]) had been given to land-hungry Polish peasants from the western provinces of the country. This meant that by the 1930s the number of Poles living within contiguous Ukrainian ethnographic territory had increased by about 300,000.[11]:586

Lithuanian lands

During the interwar period of the 20th century (1920–1939), Lithuanian–Polish relations were characterized by mutual enmity. As a consequence of the conflict over the city of Vilnius, and the Polish–Lithuanian War, both governments – in the era of nationalism which was sweeping through Europe – treated their respective minorities harshly.[82][83][84] In 1920, after the staged mutiny of Lucjan Żeligowski, Lithuanian cultural activities in Polish controlled territories were limited and the closure of Lithuanian newspapers and the arrest of their editors occurred.[85] One of them – Mykolas Biržiška was accused of state treason and sentenced to the death penalty and only the direct intervention by the League of Nations saved him from being executed. He was one of 32 Lithuanian and Belarusian cultural activists formally expelled from Vilnius on 20 September 1922 and deported to Lithuania.[85] In 1927, as tensions between Lithuania and Poland increased, 48 additional Lithuanian schools were closed and another 11 Lithuanian activists were deported.[82] Following Piłsudski's death in 1935, the Lithuanian minority in Poland again became an object of Polonization policies with greater intensity. 266 Lithuanian schools were closed after 1936 and almost all Lithuanian organizations were banned. Further Polonization ensued as the government encouraged settlement of Polish army veterans in the disputed regions.[84] About 400 Lithuanian reading rooms and libraries were closed in Poland between 1936 and 1938.[83] Following the 1938 Polish ultimatum to Lithuania, Lithuania re-established diplomatic relations with Poland and efforts to Polonize Lithuanians living in Poland decreased somewhat.

Post–World War II

During Operation Vistula of 1947, the Soviet-controlled Polish communist authorities removed the support base for the still active in that area Ukrainian Insurgent Army by forcibly resettling about 141,000 civilians residing around Bieszczady and Low Beskids to northern areas of the so-called Recovered Territories awarded by the Allies to Poland in the post-war settlement. The farmers received financial help from the Polish government and took over homes and farms left behind by the displaced Germans, in most cases improving their living conditions due to increased size of the newly reassigned properties, brick buildings, and running water.[86] Dr Zbigniew Palski from IPN explains that identical operation was performed in Ukraine by the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic at exactly the same time. It was dubbed Operation West. Both operations were coordinated from Moscow; however, there was a shocking difference between their outcomes.[86]

While Operation Vistula was underway in south-western Poland, the Soviet NKVD deported over 114,000 mostly women and children from West Ukraine to Kazakh SSR and Siberia during the parallel Operation West.[86] Only 19,000 men were among the Soviet deportees,[86] most of them sent to coal mines and stone quarries in the north. None of the families deported by the NKVD received any farms or empty homes to live in. They were instantaneously forced into extreme poverty and hunger.[86] Dr Zbigniew Palski informs also that during Operation Vistula none of the three conditions of the United Nations Charter of 26 June 1945 about the possible struggle toward their own self-determination among the Polish deportees was broken at the time. Other international laws were already in effect.[86]

References

- In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэяй. Польскі рух на беларускіх і літоўскіх землях. 1864–1917 г. / Пад рэд. С. Куль-Сяльверставай. – Гродна: ГрДУ, 2001. – 322 с. ISBN 978-5-94716-036-9 (2004). Pp.24, 28.), an additional distinction between the Polonization (Polish: polonizacja) and self-Polonization (Polish: polszczenie się) has been being made, however, most modern Polish researchers don't use the term polszczenie się.

- Michael J. Mikoś, Polish Literature from the Middle Ages to the End of the Eighteenth Century. A Bilingual Anthology, Warsaw: Constans, 1999. Introductory chapters. Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Staff writer, Encyclopædia Britannica (2006). "Ukraine." Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- Nataliia Polonska-Vasylenko, History of Ukraine, "Lybid", (1993), ISBN 5-325-00425-5, v.I, Section: "Ukraine under Poland."

- Natalia Iakovenko, Narys istorii Ukrainy s zaidavnishyh chasic do kincia XVIII stolittia, Kiev, 1997, Section: 'Ukraine-Rus.'

- Polonska-Vasylenko, Section: "Evolution of Ukrainian lands in the 15th–16th centuries."

- Staff writer, Encyclopædia Britannica (2006). "Poland, history of: Wladyslaw IV Vasa".

- Piotr S. Wandycz, United States and Poland, Harvard University Press, 1980, p. 16.

- Staff writer, Columbia Encyclopedia (2001–2005),"Ukraine".

- Staff writer, Encyclopædia Britannica (2006). "Ukraine".

- Paul Robert Magocsi. A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. 2010

- Francis Dvornik. The Slavs in European History and Civilization. Rutgers University Press. 1962. p. 307.

- Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: A History, Second Edition, 1994, University of Toronto Press, pp. 89.

- Thomas Lane. Lithuania stepping westwards. Routledge, 2001. p. 24.

- David James Smith. The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge. 2002. p. 7.

- Romuald J. Misiunas, Rein Taagepera. The Baltic States, years of dependence, 1940–1980. University of California Press. 1983. p. 3.

- Ulčinaitė E., Jovaišas A., "Lietuvių kalba ir literatūros istorija." Archived by Wayback.

- Michael J. Mikoś, Polish Renaissance Literature: An Anthology. Ed. Michael J. Mikoś. Columbus, Ohio/Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers. 1995. ISBN 0-89357-257-8, "Renaissance Literary Background." Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Nikolay Kostomarov, Russian History in Biographies of its main figures. "Little Russian Hetman Zinoviy-Bogdan Khmelnytsky." (in Russian)

- William Christian Bullitt, Jr., The Great Globe Itself: A Preface to World Affairs, Transaction Publishers, 2005, ISBN 1-4128-0490-6, Google Print, p.42-43

- John Adams, The Political Writings of John Adams, Regnery Gateway, 2001, ISBN 0-89526-292-4, Google Print, p.242

- The Confederation of Warsaw of 28th of January 1573: Religious tolerance guaranteed Archived 20 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, part of the Memory of the World project at UNESCO.

- Aleksandr Bushkov, Andrey Burovsky. Russia that was not – 2. The Russian Atlantis", ISBN 5-7867-0060-7, ISBN 5-224-01318-6

- The Prussian-Polish Situation: An experiment in Assimilation Archived 4 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine by W.I. Thomas.

- Various authors, The Treaty of Versailles: a reassessment after 75 years, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-521-62132-1, Google Print, p.314

- Roland Sussex, Paul Cubberley, The Slavic Languages, Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-521-22315-6, Google Print, p.92

- Mikhail Dolbilov, The Stereotype of the Pole in Imperial Policy: The "Depolonization" of the Northwestern Region in the 1860s, Russian Studies in History, Issue: Volume 44, Number 2 / Fall 2005, Pages: 44 – 88

- Wasilewski L. (Wasilewski 1917) Kresy Wschodnie. – Warszawa: T-wo wydawnicze w Warszawie, 1917. p. VII as cited in (Smalyanchuk 2001), p.24.

- (Dovnar 1926) pp.290–291,298.

- "In times of Myravyov the Hanger", as noted in (Wasilewski 1917), p. VII as cited in (Smalyanchuk 2001), p.24. See also the note on treatment of Polonisation as self-Polonisation.

- As noted in (Wasilewski 1917), p.42 as cited in (Smalyanchuk 2001), p.24. Also noted by Halina Turska in 1930s in "O powstaniu polskich obszarów językowych na Wileńszczyźnie", p.487 as cited in (Smalyanchuk 2001), p.25.

- As noted in (Wasilewski 1917), p.42 as cited in (Smalyanchuk 2001), p.24.

- (Dovnar 1926) pp.290–291,293–298.

- (Smalyanchuk 2001), p.28, (Dovnar 1926), pp.303–315,319–320,328–331,388–389.

- Довнар-Запольский М. В. (Mitrofan Dovnar-Zapolsky) История Белоруссии. – 2-е изд. – Мн.: Беларусь, 2005. – 680 с. ISBN 985-01-0550-X, LCCN 2003-500047

- Tomas Venclova, Four Centuries of Enlightenment. A Historic View of the University of Vilnius, 1579–1979, Lituanus, Volume 27, No.1 – Summer 1981

- Rev. Stasys Yla, The Clash of Nationalities at the University of Vilnius, Lituanus, Volume 27, No.1 – Summer 1981

- Dovnar-Zapolsky, pp.290–298.

- Dovnar-Zapolsky, pp.293–296.

- Dovnar-Zapolsky, pp.303–315,319–320,328–331.

- Harold Nicolson, The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity: 1812–1822 , Grove Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8021-3744-X, Google Print, p.171

- Prof. Anna M. Cienciala (2004). THE REBIRTH OF POLAND. University of Kansas, lecture notes. Last accessed on 2 June 2006. Quote:"there were large Polish minorities in what is today western Belarus, western Ukraine and central Ukraine. According to the Polish Census of 1931, Poles made up 5,600,000 of the total population of eastern Poland which stood at 13,021,000.* In Lithuania, Poles had majorities in the Vilnius [P. Wilno, Rus. Vilna] and Suwałki areas, as well as significant numbers in and around Kaunas [P.Kowno]."

- Roshwald, Aviel (2001). "Peace of Riga". Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, the Middle East and Russia, 1914–1923. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-415-24229-0.

- Arno Joseph Mayer, The Furies: Violence and Terror in the French and Russian Revolutions. Published by Princeton University Press, pg. 516

- History of the Jews in Russia

- Zbigniew Brzezinski in his introduction to Wacław Jędrzejewicz's "Pilsudski A Life For Poland" wrote: Pilsudski’s vision of Poland, paradoxically, was never attained. He contributed immensely to the creation of a modern Polish state, to the preservation of Poland from the Soviet invasion, yet he failed to create the kind of multinational commonwealth, based on principles of social justice and ethnic tolerance, to which he aspired in his youth. One may wonder how relevant was his image of such a Poland in the age of nationalism.... Quoted from members.lycos.co.uk Archived 14 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- Quoted in: Rogers Brubaker, Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-521-57649-0, Google Print, p.100.

- Timothy Snyder, The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10586-X No preview available. Google Books, p.144 See instead: PDF copy (5,887 KB), last accessed: 25 February 2011. Archived 19 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Feigue Cieplinski, Poles and Jews: The Quest For Self-Determination 1919–1934, Binghamton Journal of History, Fall 2002, Last accessed on 2 June 2006.

- Davies, God's Playground, op.cit.

- Eugenia Prokop-Janiec, "Polskie dziedzictwo kulturowe w nowej Europie. Humanistyka jako czynnik kształtowania tożsamości europejskiej Polaków." Research group. Subject: The frontier in the context of Polish-Jewish relations. CBR grant: Polish cultural heritage in new Europe. Humanism as a defining factor of European identity of Poles. Pogranicze polsko-żydowskie jako pogranicze kulturowe

- Photocopy of Polish text of the Riga Treaty made on March 18, 1921 Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Europa World Year, Book 1, Taylor & Francis Group, Page 713

- Per Anders Rudling (2014). The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906–1931. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 183. ISBN 9780822979586.

- Stosunki polsko-białoruskie. Bialorus.pl, Białystok, Poland. Retrieved from the Internet Archive on 9 September 2015.

- Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 34. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- Barbara Toporska (1962). "Polityka polska wobec Białorusinów".

- Сачанка, Барыс (1991). Беларуская эміграцыя [Belarusian emigration] (PDF) (in Belarusian). Minsk.

Вось што, напрыклад, заяўляў з трыбуны сейма польскі міністр асветы Скульскі: "Запэўніваю вас, паны дэпутаты, што праз якіх-небудзь дзесяць гадоў вы са свечкай не знойдзеце ні аднаго беларуса"

- Вераніка Канюта. Класікі гавораць..., Zviazda, 21 February 2014

- Аўтапартрэт на фоне класіка, Nasha Niva, 19 August 2012

- Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 12. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- Молодечно в периоды польских оккупаций.. Сайт города Молодечно (in Russian).

- Учебные материалы » Лекции » История Беларуси » ЗАХОДНЯЯ БЕЛАРУСЬ ПАД УЛАДАЙ ПОЛЬШЧЫ (1921—1939 гг.)

- Hielahajeu, Alaksandar (17 September 2014). "8 мифов о "воссоединении" Западной и Восточной Беларуси" [8 Myths about the "reunification" of West Belarus and East Belarus] (in Russian). Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 45. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- Козляков, Владимир. В борьбе за единство белорусского народа. к 75-летию воссоединения Западной Беларуси с БССР (in Russian). Белорусский государственный технологический университет / Belarusian State Technological Institute. In the struggle for the reunification of the Belarusian people – to the 75 anniversary of the reunification of West Belarus and the BSSR, by Vladimir Kosliakov. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 72. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

W najpomyślniejszym dla szkolnictw a białoruskiego roku 1928 istniało w Polsce 69 szkół w których nauczano języka białoruskiego. Wszystkie te placów ki ośw iatow e znajdow ały się w w ojew ództw ach w ileńskim i now ogródzkim, gdzie funkcjonowały 2164 szkoły polskie. Szkoły z nauczaniem języka białoruskiego, głównie utrakw istyczne, stanow iły niewiele ponad 3 procent ośrodków edukacyjnych na tym obszarze

- Матэрыялы для падрыхтоýкі да абавязковага экзамену за курс сярэняй школы: Стан культуры у Заходняй Беларусі у 1920–я-1930-я гг: характэрныя рысы і асаблівасці

- Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. pp. 41, 53, 54. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 93. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- {vn|August 2016}Andrzej Poczobut, Joanna Klimowicz (June 2011). "Białostocki ulubieniec Stalina" (PDF file, direct download 1.79 MB). Ogólnokrajowy tygodnik SZ "Związek Polaków na Białorusi" (Association of Poles of Belarus). Głos znad Niemna (Voice of the Neman weekly), Nr 7 (60). pp. 6–7 of current document. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Dr Andrew Savchenko (2009). Belarus: A Perpetual Borderland. BRILL. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-9004174481.

- An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Edited by James S. Olson. Page 95.

- Magosci, P. (1989). Morality and Reality: the Life and Times of Andrei Sheptytsky. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta.

- Paul R. Magocsi, A history of Ukraine,University of Toronto Press, 1996, p.596

- "Under Tsarist rule the Uniate population had been forcibly converted to Orthodoxy. In 1875, at least 375 Uniate Churches were converted into Orthodox churches. The same was true of many Latin-rite Roman Catholic churches." Orthodox churches were built as symbols of the Russian rule and associated by Poles with Russification during the Partition period

- Manus I. Midlarsky, "The Impact of External Threat on States and Domestic Societie" [in:] Dissolving Boundaries, Blackwell Publishers, 2003, ISBN 1-4051-2134-3, Google Print, p. 15.

- Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.

- Brief history of L'viv University Archived 2013-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Snyder, op cit, Google Print, p.146

- Timothy., Snyder (10 October 2007). Sketches from a secret war : a Polish artist's mission to liberate Soviet Ukraine. New Haven. ISBN 978-0300125993. OCLC 868007863.

- Żołędowski, Cezary (2003). Białorusini i Litwini w Polsce, Polacy na Białorusi i Litwie (in Polish). Warszawa: ASPRA-JR. ISBN 8388766767, p. 114.

- Makowski, Bronisław (1986). Litwini w Polsce 1920–1939 (in Polish). Warszawa: PWN. ISBN 83-01-06805-1, pp. 244–303.

- Fearon, James D.; Laitin, David D. (2006). "Lithuania" (PDF). Stanford University. p. 4. Retrieved 18 June 2007.

- Čepėnas, Pranas (1986). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija. Chicago: Dr. Griniaus fondas. pp. 655, 656.

- Dr Zbigniew Palski (30 May 2008). Operacja Wisła: komunistyczna akcja represyjna, czy obrona konieczna Rzeczypospolitej?. Dodatek historyczny IPN Nr. 5/2008 (12). Nasz Dziennik, Institute of National Remembrance. pp. 6–7 (3–4 in PDF). Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

External links

Further reading

- Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.

- Snyder, Timothy (2004). The reconstruction of nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10586-X.

- Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground: A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12817-7.

- Litwin Henryk, Central European Superpower, BUM Magazine, 2016.

- Tomasz Kamusella. 2013. Germanization, Polonization, and Russification in the Partitioned Lands of Poland-Lithuania (pp 815-838). Nationalities Papers. Vol 41, No 5