Nonbenzodiazepine

Nonbenzodiazepines (/ˌnɒnˌbɛnzoʊdaɪˈæzɪpiːn, -ˈeɪ-/,[1][2]) sometimes referred to colloquially as Z-drugs (as many of them begin with the letter "z"), are a class of psychoactive drugs that are very benzodiazepine-like in nature. They are used in the treatment of sleep problems.[3]

Nonbenzodiazepine pharmacodynamics are almost entirely the same as benzodiazepine drugs and therefore employ similar benefits, side-effects, and risks. However, nonbenzodiazepines have dissimilar or entirely different chemical structures and are therefore unrelated to benzodiazepines on a molecular level.[4][5]

Classes

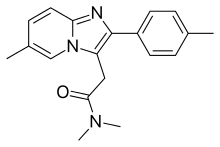

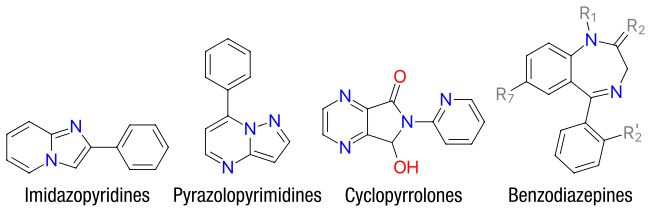

Currently, the major chemical classes of nonbenzodiazepines are:

- Alpidem

- Necopidem

- Saripidem

- Zolpidem (Ambien, Ambien CR, Intermezzo, Zolpimist, Edluar, Ivadal, Sanval, etc.)

- Divaplon

- Fasiplon

- Indiplon

- Lorediplon

- Ocinaplon

- Panadiplon

- Taniplon

- Zaleplon (Sonata, Starnoc, Andante)

|

|

Pharmacology

The nonbenzodiazepines are positive allosteric modulators of the GABA-A receptor. Like the benzodiazepines, they exert their effects by binding to and activating the benzodiazepine site of the receptor complex. Many of these compounds are subtype selective providing novel anxiolytics with little to no hypnotic and amnesiac effects and novel hypnotics with little or no anxiolytic effects.

Background

Nonbenzodiazepines have demonstrated efficacy in treating sleep disorders. There is some limited evidence that suggests that tolerance to nonbenzodiazepines is slower to develop than with benzodiazepines. However, data is limited so no conclusions can be drawn. Data is also limited into the long-term effects of nonbenzodiazepines. Further research into the safety of nonbenzodiazepines and long-term effectiveness of nonbenzodiazepines has been recommended in a review of the literature.[6] Some differences exist between the Z-drugs, for example tolerance and rebound effects may not occur with zaleplon.[7]

Pharmaceuticals

| Comparison of nonbenzodiazepines[8][9] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Reduces sleep onset latency? | Encourages sleep maintenance? | Observed causing rebound insomnia? | Observed causing physical dependence? |

| Zolpidem instant-release | Yes | Maybe | Maybe | Yes |

| Zolpidem extended-release | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sublingual zolpidem | Yes | Maybe | Maybe | Yes |

| Zolpidem oral spray | Yes | Maybe | Maybe | Yes |

| Eszopiclone | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zaleplon | Yes | Maybe | No | Yes |

The first three nonbenzodiazepine drugs to enter the market were the "Z-drugs", zopiclone, zolpidem and zaleplon. These three drugs are all sedatives used exclusively for the treatment of mild insomnia. They are safer than the older barbiturates especially in overdosage and they may, when compared to the benzodiazepines, have less of a tendency to induce physical dependence and addiction, although these issues can still become a problem. This has led to the Z-drugs becoming widely prescribed for the treatment of insomnia particularly in elderly patients.[10][11][12] A little under a third (31%) of all Americans over 65 years of age are taking Z-drugs.[13]

Long-term use is not recommended as tolerance and addiction can occur.[14] A survey of patients using nonbenzodiazepine Z drugs and benzodiazepine hypnotic users found that there was no difference in reports of adverse effects that were reported in over 41% of users and, in fact, Z drug users were more likely to report that they had tried to quit their hypnotic drug and were more likely to want to stop taking Z drugs than benzodiazepine users. Efficacy also did not differ between benzodiazepine and Z drug users.[15]

Side effects

The Z-drugs are not without disadvantages, and all three compounds are notable for producing side-effects such as pronounced amnesia and more rarely hallucinations,[16][17] especially when used in large doses. On rare occasions, these drugs can produce a fugue state, wherein the patient sleepwalks and may perform relatively complex actions, including cooking meals or driving cars, while effectively unconscious and with no recollection of the events upon awakening. While this effect is rare (and has also been reported to occur with some of the older sedative drugs such as temazepam and secobarbital), it can be potentially hazardous, and so further development of this class of drugs has continued in an effort to find new compounds with further improved profiles.[18][19][20][21][22]

Daytime withdrawal-related anxiety can also occur from chronic nightly nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic usage such as with zopiclone.[23]

Side-effects can differ within the drug class due to differences in metabolism and pharmacology. For example, long-acting benzodiazepines have problems of drug accumulation especially in the elderly or those with liver disease, and shorter-acting benzodiazepines have a higher risk of more severe withdrawal symptoms.[24][25] In the case of the nonbenzodiazepines, zaleplon may be the safest in terms of next-day sedation, and − unlike zolpidem and zopiclone − zaleplon has been found to have no association with increased motor vehicle accidents even when taken for middle-of-the-night insomnia due to its ultrashort elimination half-life.[26][27][28][29]

Increased risk of depression

It has been claimed that insomnia causes depression and hypothesized that insomnia medications may help to treat depression. In support of this claim an analysis of data of clinical trials submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concerning the drugs zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone found that these sedative hypnotic drugs more than doubled the risks of developing depression compared to those taking placebo pills. Hypnotic drugs, therefore, may be contraindicated in patients suffering from or at risk of depression. Hypnotics were found to be more likely to cause depression than to help it. Studies have found that long-term users of sedative hypnotic drugs have a markedly raised suicide risk as well as an overall increased mortality risk. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia, on the other hand, has been found to both improve sleep quality as well as general mental health.[30]

Dependence and withdrawal management

Nonbenzodiazepines should not be discontinued abruptly if taken for more than a few weeks due to the risk of rebound withdrawal effects and acute withdrawal reactions, which may resemble those seen during benzodiazepine withdrawal. Treatment usually entails gradually reducing the dosage over a period of weeks or several months depending on the individual, dosage, and length of time the drug has been taken. If this approach fails, a crossover to a benzodiazepine equivalent dose of a long-acting benzodiazepine (such as chlordiazepoxide or more preferably diazepam) can be tried followed by a gradual reduction in dosage. In extreme cases and, in particular, where severe addiction and/or abuse is manifested, an inpatient detoxification may be required, with flumazenil as a possible detoxification tool.[34][35][36]

Carcinogenicity

The Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine published a paper that had carried out a systematic review of the medical literature concerning insomnia medications and raised concerns about benzodiazepine receptor agonist drugs, the benzodiazepines, and the Z-drugs that are used as hypnotics in humans. The review found that almost all trials of sleep disorders and drugs are sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. It was found that the odds ratio for finding results favorable to industry in industry-sponsored trials was 3.6 times higher than non-industry-sponsored studies and that 24% of authors did not disclose being funded by the drug companies in their published papers when they were funded by the drug companies. The paper found that there is little research into hypnotics that is independent from the drug manufacturers. Also of concern was the lack of focus in industry-sponsored trials on their own results showing that use of hypnotics is correlated with depression.

The author was concerned that there is no discussion of adverse effects of benzodiazepine agonist hypnotics discussed in the medical literature such as significant increased levels of infection, cancers, and increased mortality in trials of hypnotic drugs and an overemphasis on the positive effects. No hypnotic manufacturer has yet tried to refute the epidemiology data that shows that use of their product is correlated with excess mortality. The author stated that "major hypnotic trials is needed to more carefully study potential adverse effects of hypnotics such as daytime impairment, infection, cancer, and death and the resultant balance of benefits and risks." The author concluded that more independent research into daytime impairment, infection, cancer, and shortening of lives of sedative hypnotic users is needed to find the true balance of benefits and risks of benzodiazepine agonist hypnotic drugs in the treatment of insomnia.[37] Significant increases in skin cancers and tumors are found in clinical trial data of the nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics compared to trial subjects having taken placebo tablets. Other cancers of the brain, lung, bowel, breast, and bladder also occurred. An increase of infections, possibly due to decreased immune function, also occurred in the nonbenzodiazepine users. It has been hypothesised that either depressed immune function or the viral infections themselves were the cause of the increased rates of cancer.

Initially, the FDA was hesitant to approve some of the nonbenzodiazepines due to concerns regarding increases in cancers. The author reported that, due to the fact that the FDA requires reporting of both favourable and unfavourable results of clinical trials, the FDA New Drug Application data is more reliable than the peer-reviewed literature, which is subject to serious bias regarding hypnotics. In 2008, the FDA analysed their data again and confirmed an increased rate of cancers in the randomised trials compared to placebos but concluded that the rate of cancers did not warrant any regulatory action.[38] Later studies on several common hypnotics found that receiving hypnotic prescriptions was associated with greater than threefold increased hazards of death even when prescribed <18 pills/year[39] and that hypnotics cause mortality through the growing U.S. overdose epidemic.[40]

Elderly

Nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drugs, similar to benzodiazepines, cause impairments in body balance and standing steadiness upon waking; falls and hip fractures are frequently reported. The combination with alcohol increases these impairments. Partial but incomplete tolerance develops to these impairments.[41] In general, nonbenzodiazepines are not recommended for older patients due to the increased risk of falls and fractures.[42] An extensive review of the medical literature regarding the management of insomnia and the elderly found that there is considerable evidence of the effectiveness and lasting benefits of non-drug treatments for insomnia in adults of all age groups and that these interventions are underused. Compared with the benzodiazepines, the nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics offer little if any advantages in efficacy or tolerability in elderly persons. It was found that newer agents such as the melatonin agonists may be more suitable and effective for the management of chronic insomnia in elderly people. Long-term use of sedative-hypnotics for insomnia lacks an evidence base and is discouraged for reasons that include concerns about such potential adverse drug effects as cognitive impairment (anterograde amnesia), daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls. In addition, the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of these agents remain to be determined. It was concluded that further research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of treatment and the most appropriate management strategy for elderly persons with chronic insomnia.[43]

Controversy

A review of the literature regarding hypnotics including the nonbenzodiazepine Z drugs concluded that these drugs cause an unjustifiable risk to the individual and to public health and lack evidence of long-term effectiveness due to tolerance. The risks include dependence, accidents, and other adverse effects. Gradual discontinuation of hypnotics leads to improved health without worsening of sleep. It is preferred that they should be prescribed for only a few days at the lowest effective dose and avoided altogether wherever possible in the elderly.[44]

New compounds

More recently, a range of non-sedating anxiolytic drugs derived from the same structural families as the Z-drugs have been developed, such as alpidem (Ananyxl) and pagoclone, and approved for clinical prescription. Nonbenzodiazepine drugs are much more selective than the older benzodiazepine anxiolytics, producing effective relief of anxiety/panic with little or no sedation, anterograde amnesia, or anticonvulsant effects, and are thus potentially more precise than older, anti-anxiety drugs. However, anxiolytic nonbenzodiazepines are not widely prescribed and many have collapsed after initial clinical trials and consumption halted many projects, including but not limited to alpidem, indiplon, and suriclone.

History

Z-drugs emerged in the last years of the 1980s and early 1990s, with zopiclone (Imovane) approved by the British National Health Service as early as 1989, quickly followed by Sanofi with zolpidem (Ambien). By 1999, King Pharmaceuticals had finalized approval with the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to market zaleplon (Sonata, Starnoc) across the US. In 2005, the FDA approved eszopiclone (Lunesta) the (S)-enantiomer of zopiclone. That same year, 2005, the FDA finalized approval for Ambien CR, or extended-release zolpidem. Most recently, in 2012 the FDA approved Intermezzo (zolpidem tartate sublingual), which is marketed for middle-of-the-night insomnia, available in doses only half of the strength of immediate-release zolpidem tartrate to avoid residual next-day sedation.

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- Z-drugs:

- Zaleplon (Sonata)

- Zolpidem (Ambien)

- Zopiclone (Imovane)

- Eszopiclone (Lunesta)

References

- "benzodiazepine - definition of benzodiazepine in English from the Oxford dictionary". OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- "benzodiazepine". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "What's wrong with prescribing hypnotics?". Drug Ther Bull. 42 (12): 89–93. December 2004. doi:10.1136/dtb.2004.421289. PMID 15587763.

- Siriwardena AN, Qureshi Z, Gibson S, Collier S, Latham M (December 2006). "GPs' attitudes to benzodiazepine and 'Z-drug' prescribing: a barrier to implementation of evidence and guidance on hypnotics". Br J Gen Pract. 56 (533): 964–7. PMC 1934058. PMID 17132386.

- Wagner J, Wagner ML, Hening WA (June 1998). "Beyond benzodiazepines: alternative pharmacologic agents for the treatment of insomnia". Ann Pharmacother. 32 (6): 680–91. doi:10.1345/aph.17111. PMID 9640488.

- Benca RM (March 2005). "Diagnosis and treatment of chronic insomnia: a review". Psychiatr Serv. 56 (3): 332–43. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.332. PMID 15746509.

- Lader MH (January 2001). "Implications of hypnotic flexibility on patterns of clinical use". Int J Clin Pract Suppl (116): 14–9. PMID 11219327.

- "Evaluating Newer Sleeping Pills Used to Treat: Insomnia: Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF). Consumer Reports. January 2012. p. 14. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Huedo-Medina TB, Kirsch I, Middlemass J, Klonizakis M, Siriwardena AN (2012). "Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". BMJ. 345: e8343. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8343. PMC 3544552. PMID 23248080.

- Neubauer DN (2006). "New approaches in managing chronic insomnia". CNS Spectrums. 11 (8 Suppl 8): 1–13. doi:10.1017/S1092852900026687. PMID 16871130.

- Najib J (2006). "Eszopiclone, a nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotic agent for the treatment of transient and chronic insomnia". Clinical Therapeutics. 28 (4): 491–516. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.04.014. PMID 16750462.

- Lieberman JA (2007). "Update on the Safety Considerations in the Management of Insomnia With Hypnotics: Incorporating Modified-Release Formulations Into Primary Care" (PDF). Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (1): 25–31. doi:10.4088/pcc.v09n0105. PMC 1894851. PMID 17599165.

- Kaufmann, Christopher N.; Spira, Adam P.; Alexander, G. Caleb; Rutkow, Lainie; Mojtabai, Ramin (2015). "Trends in prescribing of sedative-hypnotic medications in the USA: 1993–2010". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 25 (6): 637–45. doi:10.1002/pds.3951. ISSN 1099-1557. PMC 4889508. PMID 26711081.

- Touitou Y (July 2007). "[Sleep disorders and hypnotic agents: medical, social and economical impact]". Ann Pharm Fr (in French). 65 (4): 230–8. doi:10.1016/s0003-4509(07)90041-3. PMID 17652991.

- Siriwardena AN, Qureshi MZ, Dyas JV, Middleton H, Orner R (June 2008). "Magic bullets for insomnia? Patients' use and experiences of newer (Z drugs) versus older (benzodiazepine) hypnotics for sleep problems in primary care". Br J Gen Pract. 58 (551): 417–22. doi:10.3399/bjgp08X299290. PMC 2418994. PMID 18505619.

- Stone JR, Zorick TS, Tsuang J (2007). "Dose-related illusions and hallucinations with zaleplon". Clin Toxicol (Philadelphia). 46 (4): 1–2. doi:10.1080/15563650701517442. PMID 17852167.

- Toner LC, Tsambiras BM, Catalano G, Catalano MC, Cooper DS (2000). "Central nervous system side effects associated with zolpidem treatment". Clin Neuropharmacol. 23 (1): 54–8. doi:10.1097/00002826-200001000-00011. PMID 10682233.

- Mellingsaeter TC, Bramness JG, Slørdal L (2006). "[Are z-hypnotics better and safer sleeping pills than benzodiazepines?]". Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening (in Norwegian). 126 (22): 2954–6. PMID 17117195. Archived from the original on 2007-10-28.

- Yang W, Dollear M, Muthukrishnan SR (2005). "One rare side effect of zolpidem--sleepwalking: a case report". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 86 (6): 1265–6. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.022. PMID 15954071.

- Lange CL (2005). "Medication-associated somnambulism". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 44 (3): 211–2. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000150618.67559.48. PMID 15725964.

- Morgenthaler TI, Silber MH (2002). "Amnestic sleep-related eating disorder associated with zolpidem". Sleep Medicine. 3 (4): 323–7. doi:10.1016/S1389-9457(02)00007-2. PMID 14592194.

- Liskow B, Pikalov A (2004). "Zaleplon overdose associated with sleepwalking and complex behavior". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 43 (8): 927–8. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000129219.66563.aa. PMID 15266187.

- Fontaine R, Beaudry P, Le Morvan P, Beauclair L, Chouinard G (July 1990). "Zopiclone and triazolam in insomnia associated with generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled evaluation of efficacy and daytime anxiety". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 5 (3): 173–83. doi:10.1097/00004850-199007000-00002. PMID 2230061.

- Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ (June 1977). "Clinical implications of benzodiazepine pharmacokinetics". Am J Psychiatry. 134 (6): 652–6. doi:10.1176/ajp.134.6.652. PMID 17302.

- Noyes R, Perry PJ, Crowe RR, et al. (January 1986). "Seizures following the withdrawal of alprazolam". J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 174 (1): 50–2. doi:10.1097/00005053-198601000-00009. PMID 2867122.

- Menzin J, Lang KM, Levy P, Levy E (January 2001). "A general model of the effects of sleep medications on the risk and cost of motor vehicle accidents and its application to France". PharmacoEconomics. 19 (1): 69–78. doi:10.2165/00019053-200119010-00005. PMID 11252547.

- Vermeeren A, Riedel WJ, van Boxtel MP, Darwish M, Paty I, Patat A (March 2002). "Differential residual effects of zaleplon and zopiclone on actual driving: a comparison with a low dose of alcohol". Sleep. 25 (2): 224–31. PMID 11905433.

- Walsh JK; Pollak CP; Scharf MB; Schweitzer PK; Vogel GW (January–February 2000). "Lack of residual sedation following middle-of-the-night zaleplon administration in sleep maintenance insomnia". Clin Neuropharmacol. 23 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1097/00002826-200001000-00004. PMID 10682226.

- Verster JC, Veldhuijzen DS, Volkerts ER (August 2004). "Residual effects of sleep medication on driving ability". Sleep Med Rev. 8 (4): 309–25. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2004.02.001. hdl:1874/11902. PMID 15233958.

- Kripke DF (August 21, 2007). "Greater incidence of depression with hypnotic use than with placebo". BMC Psychiatry. 7: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-7-42. PMC 1994947. PMID 17711589.

- Kripke, DF (February 2016). "Mortality Risk of Hypnotics: Strengths and Limits of Evidence" (PDF). Drug Safety. 39 (2): 93–107. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0362-0. PMID 26563222.

- Treves, N; Perlman, A; Kolenberg Geron, L; Asaly, A; Matok, I (1 March 2018). "Z-drugs and risk for falls and fractures in older adults-a systematic review and meta-analysis". Age and Ageing. 47 (2): 201–208. doi:10.1093/ageing/afx167. PMID 29077902.

- Barbera J, Shapiro C (2005). "Benefit-risk assessment of zaleplon in the treatment of insomnia". Drug Saf. 28 (4): 301–18. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528040-00003. PMID 15783240.

- MedlinePlus (January 8, 2001). "Eszopiclone". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on February 27, 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- Professor Heather Ashton. "Benzodiazepines: How They Work and How to Withdraw".

- Quaglio G, Lugoboni F, Fornasiero A, Lechi A, Gerra G, Mezzelani P (September 2005). "Dependence on zolpidem: two case reports of detoxification with flumazenil infusion". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 20 (5): 285–7. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000166404.41850.b4. PMID 16096519.

- Kripke DF (December 15, 2007). "Who Should Sponsor Sleep Disorders Pharmaceutical Trials?". J Clin Sleep Med. 3 (7): 671–3. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27020. PMC 2556906. PMID 18198797.

major hypnotic trials is needed to more carefully study potential adverse effects of hypnotics such as daytime impairment, infection, cancer, and death and the resultant balance of benefits and risks.

- Kripke DF (September 2008). "Possibility that certain hypnotics might cause cancer in skin". J Sleep Res. 17 (3): 245–50. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00685.x. PMID 18844818.

- Kripke, Daniel F.; Langer, Robert D.; Kline, Lawrence E. (2012-01-01). "Hypnotics' association with mortality or cancer: a matched cohort study". BMJ Open. 2 (1): e000850. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000850. ISSN 2044-6055. PMC 3293137. PMID 22371848.

- Kripke, Daniel F. (2017-03-17). "Hypnotic drug risks of mortality, infection, depression, and cancer: but lack of benefit". F1000Research. 5: 918. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8729.2. PMC 4890308. PMID 27303633.

- Mets MA, Volkerts ER, Olivier B, Verster JC (August 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Med Rev. 14 (4): 259–67. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- Antai-Otong D (August 2006). "The art of prescribing. Risks and benefits of non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists in the treatment of acute primary insomnia in older adults". Perspect Psychiatr Care. 42 (3): 196–200. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00070.x. PMID 16916422. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06.

- Bain KT (June 2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 4 (2): 168–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- "What's wrong with prescribing hypnotics?". Drug Ther Bull. 42 (12): 89–93. December 2004. doi:10.1136/dtb.2004.421289. PMID 15587763.