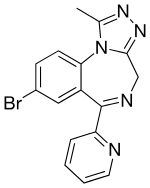

Pyrazolam

Pyrazolam (SH-I-04)[1] is a benzodiazepine derivative originally developed by a team led by Leo Sternbach at Hoffman-La Roche in the 1970s,[2] and subsequently "rediscovered" and sold as a designer drug starting in 2012.[3][4][5][6][7]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, Sublingual, rectal |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 17 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H12BrN5 |

| Molar mass | 354.211 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Pyrazolam has structural similarities to alprazolam[8] and bromazepam. Unlike other benzodiazepines, pyrazolam does not appear to undergo metabolism, instead being excreted unchanged in the urine.[3] It is most selective for the α2 and α3 subtypes of the GABAA receptor.[9]

Legal Status

United Kingdom

In the UK, pyrazolam has been classified as a Class C drug by section 5 of the May 2017 amendment to The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 along with several other designer benzodiazepine drugs.[10]

gollark: This does in fact exist.

gollark: PHP or AssemblyScript?

gollark: In that case, ALL are to use PHP?!

gollark: Really? Huh.

gollark: No, keeping Python in is required.

See also

- List of benzodiazepine designer drugs

References

- Clayton T, Poe MM, Rallapalli S, Biawat P, Savić MM, Rowlett JK, et al. (2015). "A Review of the Updated Pharmacophore for the Alpha 5 GABA(A) Benzodiazepine Receptor Model". International Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2015: 430248. doi:10.1155/2015/430248. PMC 4657098. PMID 26682068.

- US 3954728, "Preparation of triazolo benzodiazepines and novel compounds"

- Moosmann B, Hutter M, Huppertz LM, Ferlaino S, Redlingshöfer L, Auwärter V (July 2013). "Characterization of the designer benzodiazepine pyrazolam and its detectability in human serum and urine". Forensic Toxicology. 31 (2): 263–271. doi:10.1007/s11419-013-0187-4.

- Moosmann B, King LA, Auwärter V (June 2015). "Designer benzodiazepines: A new challenge". World Psychiatry. 14 (2): 248. doi:10.1002/wps.20236. PMC 4471986. PMID 26043347.

- Pettersson Bergstrand M, Helander A, Hansson T, Beck O (April 2017). "Detectability of designer benzodiazepines in CEDIA, EMIT II Plus, HEIA, and KIMS II immunochemical screening assays". Drug Testing and Analysis. 9 (4): 640–645. doi:10.1002/dta.2003. PMID 27366870.

- Høiseth G, Tuv SS, Karinen R (November 2016). "Blood concentrations of new designer benzodiazepines in forensic cases". Forensic Science International. 268: 35–38. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.09.006. PMID 27685473.

- Manchester KR, Maskell PD, Waters L (March 2018). "a and plasma protein binding values for benzodiazepines appearing as new psychoactive substances" (PDF). Drug Testing and Analysis. 10 (8): 1258–1269. doi:10.1002/dta.2387. PMID 29582576.

- Hester JB, Rudzik AD, Kamdar BV (November 1971). "6-phenyl-4H-s-triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]benzodiazepines which have central nervous system depressant activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (11): 1078–81. doi:10.1021/jm00293a015. PMID 5165540.

- Hester JB, Von Voigtlander P (November 1979). "6-Aryl-4H-s-triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]benzodiazepines. Influence of 1-substitution on pharmacological activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 22 (11): 1390–8. doi:10.1021/jm00197a021. PMID 42799.

- "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2017".

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.