Sceletium tortuosum

Sceletium tortuosum is a succulent plant commonly found in South Africa, which is also known as Kanna, Channa, Kougoed (Kauwgoed/ 'kougoed', prepared from 'fermenting' S. tortuosum[2])—which literally means, 'chew(able) things' or 'something to chew'.

| Kanna | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | Core eudicots |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | Mesembryanthemoideae |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | S. tortuosum |

| Binomial name | |

| Sceletium tortuosum | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The generally recognised eight Sceletium species are S. crassicaule, S. emarcidum, S. exalatum, S. expansum, S. rigidum, S. strictum, S. tortuosum and S. varians.[3] Per Klak et al. (2007), an alternative classification for the Sceletium group is Mesembryanthemum crassicaule, M. emarcidum, M. exalatum, M. expansum, M. archeri (S. rigidum), M. ladismithiense (S. strictum), M. tortuosum and M. varians.[3]

History

The plant has been used by South African pastoralists and hunter-gatherers as a mood-altering substance from prehistoric times.[4] The first known written account of the plant's use was in 1662 by Jan van Riebeeck. The traditionally prepared dried Sceletium was often chewed and the saliva swallowed, but it has also been made into gel caps, teas and tinctures. It has also been used as a snuff and smoked.[5]

Uses

S. tortuosum is traditionally used to fight stress and depression, relieve pain and alleviate hunger.[5]

S. tortuosum has been studied to alleviate excessive nocturnal barking in dogs and excessive nocturnal meowing in cats, both diagnosed with dementia.[4]

Effects

S. tortuosum may elevate mood and decrease anxiety, stress and tension.[3][4] Intoxicating doses can be euphoric but not hallucinogenic, contrary to some literature on the subject.[5] Sceletium tortuosum is a stimulant, in a moderate dose can cause euphoria, but in a higher dose paradoxically causes sedation.[6]

Pharmacology

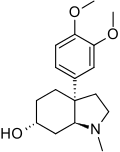

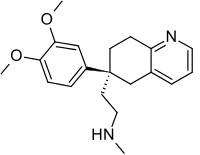

S. tortuosum contains about 1–1.5% total alkaloids.[5] The alkaloids contained in S. tortuosum believed to possess psychoactivity include mesembrine, mesembrenone, mesembrenol and tortuosamine.[5] A standardised ethanolic extract of dried S. tortuosum had an IC50 for SERT of 4.3 μg/ml and for PDE4 inhibition of 8.5 μg/ml.[3]

Kanna is also reported to be an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and cannabinoid agonist.[7]

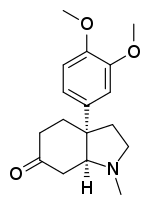

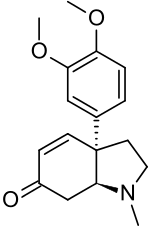

Mesembrine |  Mesembrenone |  Mesembrenol |  Tortuosamine |

Mesembrine

Mesembrine is a major alkaloid present in S. tortuosum. There is about 0.3% mesembrine in the leaves and 0.86% in the leaves, stems, and flowers of the plant.[5] It serves as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor with less prominent inhibitory effects on phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4).[3] In an in vitro study, a high-mesembrine Sceletium extract showed monoamine releasing activity by upregulation of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2).[8]

Mesembrenone

Mesembrenone on the other hand serves as a more balanced serotonin reuptake inhibitor and PDE4 inhibitor.[3]

Safety

General

Traditional and contemporary methods of preparation serve to reduce levels of potentially harmful oxalates found in S. tortuosum.[5] An analysis indicated levels of 3.6-5.1% oxalate, which falls within the median range for crop plants, just like spinach or kale.[5] It is speculated that physical crushing of the plant and the fermentation process reduce the potentially harmful effects of oxalic acid.[5] In particular, free oxalic acid is likely to complex with cell wall-associated calcium salts and precipitate as calcium oxalate when plant material is crushed.[5]

Animal studies

No treatment-related adverse effects were observed in an oral toxicity study in rats of a standardized hydroethanolic extract of S. tortuosum.[9] The extract, although not mesembrine itself, produced ataxia in rats, thereby possibly limiting the usefulness of the extract as an antidepressant.[10]

C-reactive protein levels were found to increase significantly in a dose-dependent manner in unstressed control rats but not in mildly psychologically stressed rats.[11]

Human studies

The long history of traditional human use[5] suggests that S. tortuosum may be relatively safe for human consumption, but it is important to understand the limitations of an assumption based solely on the non specific and cognitively biased idea that "if it has ever been consumed by human beings, it must be safe, even by today's standards" given the lack of modern clinical data. A 2:1 standardised extract in healthy adults at a dose of up to 25 mg once daily over a three-month period was well tolerated (human test subjects consumed small amounts daily for several months and did not feel any obvious discomfort.)[12]

See also

References

- "Monograph on sceletium tortuosum" (PDF). South African National Biodiversity Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- Smith, M. T.; Field C. R.; Crouch N. R.; Hirst, M. (1998). "The Distribution of Mesembrine Alkaloids in Selected Taxa of the Mesembryanthemaceae and their Modification in the Sceletium Derived 'Kougoed'" (PDF). Pharmaceutical Biology. 36 (3): 173–179. doi:10.1076/phbi.36.3.173.6350.

- Harvey, A. L.; Young, L. C.; Viljoen, A. M.; Gericke, N. P. (2011). "Pharmacological Actions of the South African Medicinal and Functional Food Plant Sceletium tortuosum and its Principal Alkaloids" (PDF). Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 137 (3): 1124–1129. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.035. PMID 21798331. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-30.

- Gericke, N.; Viljoen, A. M. (2008). "Sceletium--A Review Update". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 119 (3): 653–663. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.043. PMID 18761074.

- Smith, M. T.; Crouch, N. R.; Gericke, N.; Hirst, M. (1996). "Psychoactive Constituents of the Genus Sceletium N.E.Br. and other Mesembryanthemaceae: A Review". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 50 (3): 119–130. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(95)01342-3. PMID 8691846.

- https://kanna-info.com/kanna-effects

- www.ifrj.upm.edu.my (PDF) http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my/17%20(02)%202010/IFRJ-2010-349-355_Alfi_Netherlands_(S)%5B1%5D.pdf. Retrieved 2019-01-10. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Coetzee DD, López V, Smith C (2015). "High-mesembrine Sceletium extract (Trimesemine™) is a monoamine releasing agent, rather than only a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 177: 111–116. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.034. PMID 26615766.

VMAT-2 was upregulated significantly in response to Sceletium treatment. The extract showed only relatively mild inhibition of AChE and MAO-A. We conclude that the serotonin reuptake inhibition activity ascribed to the Sceletium plant, is a secondary function to the monoamine-releasing activity of high-mesembrine Sceletium extract (TrimesemineTM).

- Murbach TS, Hirka G, Szakonyiné IP, Gericke N, Endres JR (2014). "A toxicological safety assessment of a standardized extract of Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin®) in rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 74: 190–9. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2014.09.017. PMID 25301237. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

No mortality or treatment-related adverse effects were observed in male or female Crl:(WI)BR Wistar rats in the 14- or 90-day studies. In the 14- and 90-day studies, the NOAELs were concluded as 5000 and 600 mg/kg bw/d, respectively, the highest dose groups tested.

- Loria MJ, Ali Z, Abe N, Sufka KJ, Khan IA (2014). "Effects of Sceletium tortuosum in rats". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 155 (1): 731–5. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.06.007. PMID 24930358. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

Mesembrine appears to have analgesic properties without abuse liabilities or ataxia. The Sceletium tortuosum fraction has antidepressant properties but does produce ataxia. The ataxia may limit its usefulness as an antidepressant unless the antidepressant activity is associated with one constituent and the ataxia is associated with a separate constituent.

- Smith C (2011). "The effects of Sceletium tortuosum in an in vivo model of psychological stress". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 133 (1): 31–6. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.058. PMID 20816940. Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- Nell H, Siebert M, Chellan P, Gericke N (2013). "A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial of Extract Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin) in healthy adults". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 19 (11): 898–904. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0185. PMID 23441963. Retrieved 2015-06-29.

Both doses of extract Sceletium tortuosum (Zembrin) (8 mg and 25 mg) were well tolerated when used by healthy human subjects once daily for 3 months.

Further reading

- van Wyk, Ben-Erik; van Oudtshoorn, Bosch; Gericke, Nigel (2009). Medicinal Plants of South Africa (2nd ed.). Pretoria, South Africa: Briza Publications. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-875093-37-3.