Crete

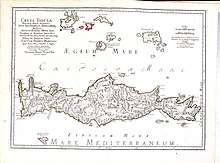

Crete (Greek: Κρήτη, Modern: Kríti, ['kriti], Ancient: Krḗtē, [krέːtεː]; Egyptian: 𓎡𓆑𓍘𓅱𓈉, keftiu; Biblical Hebrew: כפתור, caphtor; Turkish: Girit) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus and Corsica. It bounds the southern border of the Aegean sea. Crete lies approximately 160 km (99 mi) south of the Greek mainland. It has an area of 8,336 km2 (3,219 sq mi) and a coastline of 1,046 km (650 mi).

| Native name: Κρήτη | |

|---|---|

NASA photograph of Crete | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Eastern Mediterranean |

| Coordinates | 35°12.6′N 24°54.6′E |

| Area | 8,450 km2 (3,260 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 88 |

| Highest elevation | 2,456 m (8,058 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Ida (Psiloritis) |

| Administration | |

| Region | Crete |

| Capital city | Heraklion |

| Largest settlement | Heraklion (pop. 211,370[1]) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Cretan, archaic Cretian |

| Population | 634,930 (2019) |

| Population rank | 73 |

| Pop. density | 75/km2 (194/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Greeks; historically, Minoans, Eteocretans, Cydonians and Pelasgians |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| HDI (2018) 0.870[2] very high · 2nd | |

Crete and a number of islands and islets that surround it constitute the Region of Crete (Greek: Περιφέρεια Κρήτης), which is the southernmost of the 13 top-level administrative units of Greece, and the fifth most populous of Greece‘s regions. Its capital and largest city is Heraklion, located on the north shore of the island. As of 2011, the region had a population of 623,065. The Dodecanese are located to the northeast of Crete, while the Cyclades are situated to the north, separated by the Sea of Crete. The Peloponnese is to the region's northwest.

Humans have inhabited the island since at least 130,000 years ago, during the Paleolithic age. Crete was the centre of Europe's first advanced civilization, the Minoans, from 2700 to 1420 BC. The Minoan civilization was overrun by the Mycenaean civilization from mainland Greece. Crete was later ruled by Rome, then successively by the Byzantine Empire, Andalusian Arabs, the Venetian Republic, and the Ottoman Empire. In 1898, the Cretan people, who had for some time wanted to join the Greek state, achieved independence from the Ottomans, formally becoming as the Cretan State. Crete became part of Greece in December 1913.

The island is mostly mountainous, and its character is defined by a high mountain range crossing from west to east. It includes Crete's highest point, Mount Ida, and the range of the White Mountains (Lefka Ori) with 30 summits above 2000 metres in altitude and the Samaria Gorge, a World Biosphere Reserve. Crete forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece, while retaining its own local cultural traits (such as its own poetry and music). The Nikos Kazantzakis airport at Heraklion and the Daskalogiannis airport at Chania serve international travelers. The palace of Knossos, a Bronze Age settlement and ancient Minoan city, lies in Heraklion in Crete.[3]

Name

| Keftiu in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The earliest references to the island of Crete come from texts from the Syrian city of Mari dating from the 18th century BC, where the island is referred to as Kaptara.[4] This is repeated later in Neo-Assyrian records and the Bible (Caphtor). It was known in ancient Egyptian as Keftiu or kftı͗w, strongly suggesting a similar Minoan name for the island.[5]

The current name "Crete" is first attested in the 15th century BC in Mycenaean Greek texts, written in Linear B, through the words ke-re-te (*Krētes; later Greek: Κρῆτες [krɛː.tes], plural of Κρής [krɛːs])[6] and ke-re-si-jo (*Krēsijos; later Greek: Κρήσιος [krέːsios],[7] "Cretan").[8][9] In Ancient Greek, the name Crete (Κρήτη) first appears in Homer's Odyssey.[10]

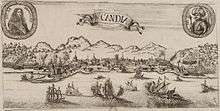

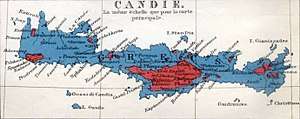

In Latin, the name of the island became Creta. The original Arabic name of Crete was Iqrīṭiš (Arabic: اقريطش < (της) Κρήτης), but after the Emirate of Crete's establishment of its new capital at ربض الخندق Rabḍ al-Ḫandaq (modern Iraklion), both the city and the island became known as Χάνδαξ (Chandax) or Χάνδακας (Chandakas), which gave Latin, Italian, and Venetian Candia, from which were derived French Candie and English Candy or Candia. Under Ottoman rule, in Ottoman Turkish, Crete was called Girit (كريت).

Physical geography

.jpg)

Crete is the largest island in Greece and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is located in the southern part of the Aegean Sea separating the Aegean from the Libyan Sea.

Island morphology

The island has an elongated shape: it spans 260 km (160 mi) from east to west, is 60 km (37 mi) at its widest point, and narrows to as little as 12 km (7.5 mi) (close to Ierapetra). Crete covers an area of 8,336 km2 (3,219 sq mi), with a coastline of 1,046 km (650 mi); to the north, it broaches the Sea of Crete (Greek: Κρητικό Πέλαγος); to the south, the South Cretian Sea (Greek: Νότιο Κρητικό Πέλαγος); in the west, the Myrtoan Sea, and toward the east the Karpathian Sea. It lies approximately 160 km (99 mi) south of the Greek mainland.

Mountains and valleys

Crete is mountainous, and its character is defined by a high mountain range crossing from west to east, formed by six different groups of mountains:

- The White Mountains or Lefka Ori 2,454 m (8,051 ft)

- The Idi Range (Psiloritis 35.18°N 24.82°E 2,456 m (8,058 ft)

- Asterousia Mountains 1,231 m (4,039 ft)

- Kedros 1,777 m (5,830 ft)

- The Dikti Mountains 2,148 m (7,047 ft)

- Thripti 1,489 m (4,885 ft)

These mountains lavish Crete with valleys, such as Amari valley, fertile plateaus, such as Lasithi plateau, Omalos and Nidha; caves, such as Gourgouthakas, Diktaion, and Idaion (the birthplace of the ancient Greek god Zeus); and a number of gorges.

Mountains in Crete are the object of tremendous fascination both for locals and tourists. The mountains have been seen as a key feature of the island's distinctiveness, especially since the time of Romantic travellers' writing. Contemporary Cretans distinguish between highlanders and lowlanders; the former often claim to reside in places affording a higher/better climatic but also moral environment. In keeping with the legacy of Romantic authors, the mountains are seen as having determined their residents' 'resistance' to past invaders which relates to the oft-encountered idea that highlanders are 'purer' in terms of less intermarriages with occupiers. For residents of mountainous areas, such as Sfakia in western Crete, the aridness and rockiness of the mountains is emphasised as an element of pride and is often compared to the alleged soft-soiled mountains of others parts of Greece or the world.[11]

Gorges, rivers and lakes

The island has a number of gorges, such as the Samariá Gorge, Imbros Gorge, Kourtaliotiko Gorge, Ha Gorge, Platania Gorge, the Gorge of the Dead (at Kato Zakros, Sitia) and Richtis Gorge and (Richtis) waterfall at Exo Mouliana in Sitia.[12][13][14][15]

The rivers of Crete include the Ieropotamos River, the Koiliaris, the Anapodiaris, the Almiros, the Giofyros, and Megas Potamos. There are only two freshwater lakes in Crete: Lake Kournas and Lake Agia, which are both in Chania regional unit.[16] Lake Voulismeni at the coast, at Aghios Nikolaos, was formerly a freshwater lake but is now connected to the sea, in Lasithi.[17] Artificial lakes created by dams also exist in Crete; there are three, i.e. the lake of Aposelemis Dam, the lake of Potamos Dam, and the lake of Mpramiana Dam.

Aradaina Gorge

Aradaina Gorge Venetian Bridge over Megalopotamos River

Venetian Bridge over Megalopotamos River

Surrounding islands

A large number of islands, islets, and rocks hug the coast of Crete. Many are visited by tourists, some are only visited by archaeologists and biologists. Some are environmentally protected. A small sample of the islands includes:

- Gramvousa (Kissamos, Chania) the pirate island opposite the Balo lagoon

- Elafonisi (Chania), which commemorates a shipwreck and an Ottoman massacre

- Chrysi island (Ierapetra, Lasithi), which hosts the largest natural Lebanon cedar forest in Europe

- Paximadia island (Agia Galini, Rethymno) where the god Apollo and the goddess Artemis were born

- The Venetian fort and leper colony at Spinalonga opposite the beach and shallow waters of Elounda (Agios Nikolaos, Lasithi)

- Dionysades islands which are in an environmentally protected region together the Palm Beach Forest of Vai in the municipality of Sitia, Lasithi

Off the south coast, the island of Gavdos is located 26 nautical miles (48 km) south of Hora Sfakion and is the southernmost point of Europe.

Climate

Crete straddles two climatic zones, the Mediterranean and the North African, mainly falling within the former. As such, the climate in Crete is primarily Mediterranean. The atmosphere can be quite humid, depending on the proximity to the sea, while winter is fairly mild. Snowfall is common on the mountains between November and May, but rare in the low-lying areas. While some mountain tops are snow-capped for most of the year, near the coast snow only stays on the ground for a few minutes or hours. However, a truly exceptional cold snap swept the island in February 2004, during which period the whole island was blanketed with snow. During the Cretan summer, average temperatures reach the high 20s-low 30s Celsius (mid 80s to mid 90s Fahrenheit), with maxima touching the upper 30s-mid 40s.

The south coast, including the Mesara Plain and Asterousia Mountains, falls in the North African climatic zone, and thus enjoys significantly more sunny days and high temperatures throughout the year. There, date palms bear fruit, and swallows remain year-round rather than migrate to Africa. The fertile region around Ierapetra, on the southeastern corner of the island, is renowned for its exceptional year-round agricultural production, with all kinds of summer vegetables and fruit produced in greenhouses throughout the winter.[18] Western Crete (Chania province) receives more rain and is more erosive compared to the Eastern part of Crete.[19]

Geography

Crete is the most populous island in Greece with a population of more than 600,000 people. Approximately 42% live in Crete's main cities and towns whilst 45% live in rural areas.[20]

Administration

Crete Region Περιφέρεια Κρήτης | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Coordinates: 35°13′N 24°55′E | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1912 |

| Capital | Heraklion |

| Regional units | |

| Government | |

| • Regional governor | Stavros Arnaoutakis (PASOK) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8,335.88 km2 (3,218.50 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[21] | |

| • Total | 623,065 |

| • Density | 75/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | GR-M |

| Website | www |

Crete with its nearby islands form the Crete Region (Greek: Περιφέρεια Κρήτης, Periféria Krítis, [periˈferia ˈkritis]), one of the 13 regions of Greece which were established in the 1987 administrative reform.[22] Under the 2010 Kallikratis plan, the powers and authority of the regions were redefined and extended. The region is based at Heraklion and is divided into four regional units (pre-Kallikratis prefectures). From west to east these are: Chania, Rethymno, Heraklion, and Lasithi. These are further subdivided into 24 municipalities.

The region's governor is, since 1 January 2011, Stavros Arnaoutakis, who was elected in the November 2010 local administration elections for the Panhellenic Socialist Movement.

Cities

Heraklion is the largest city and capital of Crete. Chania was the capital until 1971. The principal cities are:

Economy

The economy of Crete is predominantly based on services and tourism. However, agriculture also plays an important role and Crete is one of the few Greek islands that can support itself independently without a tourism industry.[24] The economy began to change visibly during the 1970s as tourism gained in importance. Although an emphasis remains on agriculture and stock breeding, because of the climate and terrain of the island, there has been a drop in manufacturing, and an observable expansion in its service industries (mainly tourism-related). All three sectors of the Cretan economy (agriculture/farming, processing-packaging, services), are directly connected and interdependent. The island has a per capita income much higher than the Greek average, whereas unemployment is at approximately 4%, one-sixth of that of the country overall.

As in many regions of Greece, viticulture and olive groves are significant; oranges, citrons and avocadoes are also cultivated. Until recently there were restrictions on the import of bananas to Greece, therefore bananas were grown on the island, predominantly in greenhouses. Dairy products are important to the local economy and there are a number of speciality cheeses such as mizithra, anthotyros, and kefalotyri.

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the region was 9.4 billion € in 2018, accounting for 5.1% of Greek economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 17,800 € or 59% of the EU27 average in the same year. The GDP per employee was 68% of the EU average. Crete is the region in Greece with the fifth highest GDP per capita.[25]

Transport infrastructure

Airports

The island has three significant airports, Nikos Kazantzakis at Heraklion, the Daskalogiannis airport at Chania and a smaller one in Sitia. The first two serve international routes, acting as the main gateways to the island for travellers. There is a long-standing plan to replace Heraklion airport with a completely new airport at Kastelli, where there is presently an air force base.

Ferries

The island is well served by ferries, mostly from Athens, by ferry companies such as Minoan Lines and ANEK Lines.

Road Network

Although the road network leads almost everywhere, there is a lack of modern highways, although this is gradually changing with the completion of the northern coastal spine highway.[26] In addition, a European study has been devised from European Union to promote a modern highway that will connect the North and the South parts of the island via a tunnel. According to the study the project should be include 15.7 km of section of road between the villages Agia Varvara and Agia Deka in central Crete, benefits both tourists and local people by improving the accessibility to the southern part of the island and lessen the accidents. The new road section forms part of the route between Messara in the south and Crete's capital city Heraklion, which provides the island's airport and principal sea port link with mainland Greece. Traffic speeds on the new road will increase by 19 km/hour (from 29 km/hours to 48 km/hour), which should reduce journey times between Messara and Heraklion by 55 minutes. The scheme is also expected to improve road safety by cutting the number of accidents along the route. Building works include construction of three road tunnels, five bridges and three junctions. This project is expected to create 44 jobs during the implementation phase.

The investment falls under Greece's "Improvement of Accessibility" Operational Programme. The programme aims to improve the country's transport infrastructures as well as its international connections. It will therefore have a key role to play in making Greece's remote and landlocked regions more accessible and economically attractive. This Operational Programme works to link Greece's more prosperous and less developed regions, which should help to promote greater territorial cohesion.

Total investment for the project "Completion of construction of the section of Ag. Varvara - Ag. Deka (Kastelli) (22+170 km to 37+900 km) of the vertical road axis Irakleio – Messara in the prefecture of Irakleio, Kriti" is EUR 102 273 321, of which the EU's European Regional Development Fund is contributing EUR 86 932 323 from the Operational Programme "Improvement of Accessibility" for the 2007 to 2013 programming period. Work falls under the priority "Road Transport – trans-European and trans-regional route network of the regions on the Convergence objective".[27]

Railway

Also, during the 1930s there was a narrow-gauge industrial railway in Heraklion, from Giofyros in the west side of the city to the port. There are now no railway lines on Crete. The government is planning the construction of a line from Chania to Heraklion via Rethymno.[28][29]

Development

Newspapers have reported that the Ministry of Mercantile Marine is ready to support the agreement between Greece, South Korea, Dubai Ports World and China for the construction of a large international container port and free trade zone in southern Crete near Tympaki; the plan is to expropriate 850 ha of land. The port would handle 2 million containers per year, but the project has not been universally welcomed because of its environmental, economic and cultural impact.[30] As of January 2013, the project has still not been confirmed, although there is mounting pressure to approve it, arising from Greece's difficult economic situation.

There are plans for underwater cables going from mainland Greece to Israel and Egypt passing by Crete and Cyprus: EuroAfrica Interconnector and EuroAsia Interconnector.[31][32] They would connect Crete electrically with mainland Greece, ending energy isolation of Crete. Now Hellenic Republic covers for Crete electricity costs difference of around €300 million per year.[33]

History

.jpg)

Hominids settled in Crete at least 130,000 years ago. In the later Neolithic and Bronze Age periods, under the Minoans, Crete had a highly developed, literate civilization. It has been ruled by various ancient Greek entities, the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the Emirate of Crete, the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. After a brief period of independence (1897–1913) under a provisional Cretan government, it joined the Kingdom of Greece. It was occupied by Nazi Germany during the Second World War.

Prehistoric Crete

In 2002, the paleontologist Gerard Gierlinski discovered fossil footprints left by ancient human relatives 5,600,000 years ago.[34]

The first human settlement in Crete dates before 130,000 years ago, during the Paleolithic age.[35][36][37] Settlements dating to the aceramic Neolithic in the 7th millennium BC, used cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and dogs as well as domesticated cereals and legumes; ancient Knossos was the site of one of these major Neolithic (then later Minoan) sites.[38] Other neolithic settlements include those at Kephala, Magasa, and Trapeza.

Minoan civilization

Crete was the centre of Europe's first advanced civilization, the Minoan (c. 2700–1420 BC).[3] This civilization wrote in the undeciphered script known as Linear A. Early Cretan history is replete with legends such as those of King Minos, Theseus and the Minotaur, passed on orally via poets such as Homer. The volcanic eruption of Thera may have been the cause of the downfall of the Minoan civilization.

Mycenaean civilization

In 1420 BC, the Minoan civilization was overrun by the Mycenaean civilization from mainland Greece. The oldest samples of writing in the Greek language, as identified by Michael Ventris, is the Linear B archive from Knossos, dated approximately to 1425–1375 BC.[39]

Archaic and Classical period

After the Bronze Age collapse, Crete was settled by new waves of Greeks from the mainland. A number of city states developed in the Archaic period. There was very limited contact with mainland Greece, and Greek historiography shows little interest in Crete, and as a result, there are very few literary sources.

During the 6th to 4th centuries BC, Crete was comparatively free from warfare. The Gortyn code (5th century BC) is evidence for how codified civil law established a balance between aristocratic power and civil rights.

In the late 4th century BC, the aristocratic order began to collapse due to endemic infighting among the elite, and Crete's economy was weakened by prolonged wars between city states. During the 3rd century BC, Gortyn, Kydonia (Chania), Lyttos and Polyrrhenia challenged the primacy of ancient Knossos.

While the cities continued to prey upon one another, they invited into their feuds mainland powers like Macedon and its rivals Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt. In 220 BC the island was tormented by a war between two opposing coalitions of cities. As a result, the Macedonian king Philip V gained hegemony over Crete which lasted to the end of the Cretan War (205–200 BC), when the Rhodians opposed the rise of Macedon and the Romans started to interfere in Cretan affairs.

In the 2nd century BC Ierapytna (Ierapetra) gained supremacy on eastern Crete.

Roman rule

Crete was involved in the Mithridatic Wars, initially repelling an attack by Roman general Marcus Antonius Creticus in 71 BC. Nevertheless, a ferocious three-year campaign soon followed under Quintus Caecilius Metellus, equipped with three legions and Crete was finally conquered by Rome in 69 BC, earning for Metellus the title "Creticus". Gortyn was made capital of the island, and Crete became a Roman province, along with Cyrenaica that was called Creta et Cyrenaica. Archaeological remains suggest that Crete under Roman rule witnessed prosperity and increased connectivity with other parts of the Empire.[40] In the 2nd century AD, at least three cities in Crete (Lyttos, Gortyn, Hierapytna) joined the Panhellenion, a league of Greek cities founded by the emperor Hadrian. When Diocletian redivided the Empire, Crete was placed, along with Cyrene, under the diocese of Moesia, and later by Constantine I to the diocese of Macedonia.

Byzantine Empire – first period

Crete was separated from Cyrenaica c. 297. It remained a province within the eastern half of the Roman Empire, usually referred to as the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire after the establishment of a second capital in Constantinople by Constantine in 330. Crete was subjected to an attack by Vandals in 467, the great earthquakes of 365 and 415, a raid by Slavs in 623, Arab raids in 654 and the 670s, and again in the 8th century. In c. 732, the Emperor Leo III the Isaurian transferred the island from the jurisdiction of the Pope to that of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.[41]

Andalusian Arab rule

In the 820s, after 900 years as a Roman, and then Eastern Roman (Byzantine) island, Crete was captured by Andalusian Muladis led by Abu Hafs,[42] who established the Emirate of Crete. The Byzantines launched a campaign that took most of the island back in 842 and 843 under Theoktistos. Further Byzantine campaigns in 911 and 949 failed. In 960/1, Nikephoros Phokas' campaign completely restored Crete to the Byzantine Empire, after a century and a half of Arab control.

Byzantine Empire – second period

In 961, Nikephoros Phokas returned the island to Byzantine rule after expelling the Arabs.[43] Extensive efforts at conversion of the populace were undertaken, led by John Xenos and Nikon "the Metanoeite".[44][45] The reconquest of Crete was a major achievement for the Byzantines, as it restored Byzantine control over the Aegean littoral and diminished the threat of Saracen pirates, for which Crete had provided a base of operations.

In 1204, the Fourth Crusade seized and sacked the imperial capital of Constantinople. Crete was initially granted to leading Crusader Boniface of Montferrat[43] in the partition of spoils that followed. However, Boniface sold his claim to the Republic of Venice,[43] whose forces made up the majority of the Crusade. Venice's rival the Republic of Genoa immediately seized the island and it was not until 1212 that Venice secured Crete as a colony.

Venetian rule

From 1212, during Venice's rule, which lasted more than four centuries, a Renaissance swept through the island as is evident from the plethora of artistic works dating to that period. Known as The Cretan School or Post-Byzantine Art, it is among the last flowerings of the artistic traditions of the fallen empire. The most notable representatives of this Cretan renaissance were the painter El Greco and the writers Nicholas Kalliakis (1645–1707), Georgios Kalafatis (professor) (c. 1652–1720), Andreas Musalus (c. 1665–1721) and Vitsentzos Kornaros.[46][47][48]

Under the rule of the Catholic Venetians, the city of Candia was reputed to be the best fortified city of the Eastern Mediterranean.[49] The three main forts were located at Gramvousa, Spinalonga, and Fortezza at Rethymnon. Other fortifications include the Kazarma fortress at Sitia. In 1492, Jews expelled from Spain settled on the island.[50] In 1574–77, Crete was under the rule of Giacomo Foscarini as Proveditor General, Sindace and Inquisitor. According to Starr's 1942 article, the rule of Giacomo Foscarini was a Dark Age for Jews and Greeks. Under his rule, non-Catholics had to pay high taxes with no allowances. In 1627, there were 800 Jews in the city of Candia, about seven percent of the city's population.[51] Marco Foscarini was the Doge of Venice during this time period.

Ottoman rule

The Ottomans conquered Crete in 1669, after the siege of Candia. Many Greek Cretans fled to other regions of the Republic of Venice after the Ottoman–Venetian Wars, some even prospering such as the family of Simone Stratigo (c. 1733 – c. 1824) who migrated to Dalmatia from Crete in 1669.[52] Islamic presence on the island, aside from the interlude of the Arab occupation, was cemented by the Ottoman conquest. Most Cretan Muslims were local Greek converts who spoke Cretan Greek, but in the island's 19th-century political context they came to be viewed by the Christian population as Turks.[53] Contemporary estimates vary, but on the eve of the Greek War of Independence (1830), as much as 45% of the population of the island may have been Muslim.[54] A number of Sufi orders were widespread throughout the island, the Bektashi order being the most prevalent, possessing at least five tekkes. Many Cretan Turks fled Crete because of the unrest, settling in Turkey, Rhodes, Syria, Libya and elsewhere. By 1900, 11% of the population was Muslim. Those remaining were relocated in the 1924 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.[55]

During Easter of 1770, a notable revolt against Ottoman rule, in Crete, was started by Daskalogiannis, a shipowner from Sfakia who was promised support by Orlov's fleet which never arrived. Daskalogiannis eventually surrendered to the Ottoman authorities. Today, the airport at Chania is named after him.

Crete was left out of the modern Greek state by the London Protocol of 1830, and soon it was yielded to Egypt by the Ottoman sultan. Egyptian rule was short-lived and sovereignty was returned to the Ottoman Empire by the Convention of London on 3 July 1840.

Heraklion was surrounded by high walls and bastions and extended westward and southward by the 17th century. The most opulent area of the city was the northeastern quadrant where all the elite were gathered together. The city had received another name under the rule of the Ottomans, "the deserted city".[49] The urban policy that the Ottoman applied to Candia was a two-pronged approach.[49] The first was the religious endowments. It made the Ottoman elite contribute to building and rehabilitating the ruined city. The other method was to boost the population and the urban revenue by selling off urban properties. According to Molly Greene (2001) there were numerous records of real-estate transactions during the Ottoman rule. In the deserted city, minorities received equal rights in purchasing property. Christians and Jews were also able to buy and sell in the real-estate market.

The Cretan Revolt of 1866–1869 or Great Cretan Revolution (Greek: Κρητική Επανάσταση του 1866) was a three-year uprising against Ottoman rule, the third and largest in a series of revolts between the end of the Greek War of Independence in 1830 and the establishment of the independent Cretan State in 1898. A particular event which caused strong reactions among the liberal circles of western Europe was the Holocaust of Arkadi. The event occurred in November 1866, as a large Ottoman force besieged the Arkadi Monastery, which served as the headquarters of the rebellion. In addition to its 259 defenders, over 700 women and children had taken refuge in the monastery. After a few days of hard fighting, the Ottomans broke into the monastery. At that point, the abbot of the monastery set fire to the gunpowder stored in the monastery's vaults, causing the death of most of the rebels and the women and children sheltered there.

Cretan State 1898–1908

Following the repeated uprisings in 1841, 1858, 1889, 1895 and 1897 by the Cretan people, who wanted to join Greece, the Great Powers decided to restore order and in February 1897 sent in troops. The island was subsequently garrisoned by troops from Great Britain, France, Italy and Russia; Germany and Austro-Hungary withdrawing from the occupation in early 1898. During this period Crete was governed through a committee of admirals from the remaining four Powers. In March 1898 the Powers decreed, with the very reluctant consent of the Sultan, that the island would be granted autonomy under Ottoman suzerainty in the near future.[56]

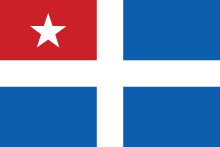

In September 1898 an outbreak of rioting in Candia, modern Heraklion, left over 500 Cretan Christians, and 14 British servicemen, dead. As a result, the Admirals ordered the expulsion of all Ottoman troops and administrators from the island, a move that was ultimately completed by early November. The decision to grant autonomy to the island was enforced and a High Commissioner, Prince George of Greece, appointed, arriving to take up his post in December 1898.[57] The flag of the Cretan State was chosen by the Powers, with the white star representing the Ottoman suzerainty over the island.

In 1905, disagreements between Prince George and minister Eleftherios Venizelos over the question of the enosis (union with Greece), such as the Prince's autocratic style of government, resulted in the Theriso revolt, one of the leaders being Eleftherios Venizelos.

Prince George resigned as High Commissioner and was replaced by Alexandros Zaimis, a former Greek prime minister, in 1906. In 1908, taking advantage of domestic turmoil in Turkey as well as the timing of Zaimis's vacation away from the island, the Cretan deputies unilaterally declared union with Greece.

With the break out of the First Balkan War, the Greek government declared that Crete was now Greek territory. This was not recognised internationally until 1 December 1913.[57]

Second World War

During World War II, the island was the scene of the famous Battle of Crete in May 1941. The initial 11-day battle was bloody and left more than 11,000 soldiers and civilians killed or wounded. As a result of the fierce resistance from both Allied forces and civilian Cretan locals, the invasion force suffered heavy casualties, and Adolf Hitler forbade further large-scale paratroop operations for the rest of the war. During the initial and subsequent occupation, German firing squads routinely executed male civilians in reprisal for the death of German soldiers; civilians were rounded up randomly in local villages for the mass killings, such as at the Massacre of Kondomari and the Viannos massacres. Two German generals were later tried and executed for their roles in the killing of 3,000 of the island's inhabitants.[58]

Tourism

Crete was one of the most popular holiday destinations in Greece. 15% of all arrivals in Greece come through the city of Heraklion (port and airport), while charter journeys to Heraklion seven years ago made up 20% of all charter flights in Greece. Overall, more than two million tourists visited Crete some years back, when the increase in tourism was reflected in the number of hotel beds, rising by 53% in the period between 1986 and 1991.

Today, the island's tourism infrastructure caters to all tastes, including a very wide range of accommodation; the island's facilities take in large luxury hotels with their complete facilities, swimming pools, sports and recreation, smaller family-owned apartments, camping facilities and others. Visitors reach the island via two international airports in Heraklion and Chania and a smaller airport in Sitia (international charter and domestic flights starting May 2012)[59] or by boat to the main ports of Heraklion, Chania, Rethimno, Agios Nikolaos and Sitia.

Popular tourist attractions include the archaeological sites of the Minoan civilisation, the Venetian old city and port of Chania, the Venetian castle at Rethymno, the gorge of Samaria, the islands of Chrysi, Elafonisi, Gramvousa, Spinalonga and the Palm Beach of Vai, which is the largest natural palm forest in Europe.

Transportation

Crete has an extensive bus system with regular services across the north of the island and from north to south. There are two regional bus stations in Heraklion. Bus routes and timetables can be found on KTEL website.[60]

Holiday homes and immigration

Crete's mild climate attracts interest from northern Europeans who want a holiday home or residence on the island. EU citizens have the right to freely buy property and reside with little formality.[61] A growing number of real estate companies cater to mainly British immigrants, followed by German, Dutch, Scandinavian and other European nationalities wishing to own a home in Crete. The British immigrants are concentrated in the western regional units of Chania and Rethymno and to a lesser extent in Heraklion and Lasithi.[28]

Archaeological sites and museums

The area has a large number of archaeological sites, including the Minoan sites of Knossos, Malia (not to be confused with the town of the same name), Petras and Phaistos, the classical site of Gortys, and the diverse archaeology of the island of Koufonisi, which includes Minoan, Roman, and World War II era ruins (nb. due to conservation concerns, access to the latter has been restricted for the last few years, so it is best to check before heading to a port).

There are a number of museums throughout Crete. The Heraklion Archaeological Museum displays most of the archaeological finds from the Minoan era and was reopened in 2014.[62]

Harmful effects

Helen Briassoulis proposed in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism that Crete is a victim of external tourist systems applying pressure to it to develop at an unhealthy rate, and that informal, internal systems within the country are forced to adapt. According to her, these forces have strengthened in 3 stages: from the period from 1960–1970, 1970–1990, and 1990 to the present. During this first period, tourism was a largely positive force, pushing modern developments like running water and electricity onto the largely rural countryside. However, beginning in the second period and especially in the third period leading up to the present day, tourist companies became more pushy with deforestation and pollution of Crete's natural resources. The country is then pulled into an interesting parity, where these companies only upkeep those natural resources that are directly essential to their industry.

View of Gortyn

View of Gortyn.jpg) Archaeological site of Phaistos

Archaeological site of Phaistos Ruins of the Palace of Knossos

Ruins of the Palace of Knossos Archeological Museum of Chania

Archeological Museum of Chania_2.jpg)

Chania Naval museum

Chania Naval museum

Jars in Malia, Crete

Jars in Malia, Crete

Fauna and flora

Fauna

Crete is isolated from mainland Europe, Asia, and Africa, and this is reflected in the diversity of the fauna and flora. As a result, the fauna and flora of Crete have many clues to the evolution of species. There are no animals that are dangerous to humans on the island of Crete in contrast to other parts of Greece. Indeed, the ancient Greeks attributed the lack of large mammals such as bears, wolves, jackals, and venomous snakes, to the labour of Hercules (who took a live Cretan bull to the Peloponnese). Hercules wanted to honor the birthplace of Zeus by removing all "harmful" and "venomous" animals from Crete. Later, Cretans believed that the island was cleared of dangerous creatures by the Apostle Paul, who lived on the island of Crete for two years, with his exorcisms and blessings. There is a natural history museum, the Natural History Museum of Crete, operating under the direction of the University of Crete and two aquariums – Aquaworld in Hersonissos and Cretaquarium in Gournes, displaying sea creatures common in Cretan waters.

Prehistoric fauna

Dwarf elephants, dwarf hippopotamus, dwarf mammoths, dwarf deer, and giant flightless owls were native to Pleistocene Crete.[63][64]

Mammals

Mammals of Crete include the vulnerable kri-kri, Capra aegagrus cretica that can be seen in the national park of the Samaria Gorge and on Thodorou,[65] Dia and Agioi Pantes (islets off the north coast), the Cretan wildcat and the Cretan spiny mouse.[66][67][68][69] Other terrestrial mammals include subspecies of the Cretan marten, the Cretan weasel, the Cretan badger, the long-eared hedgehog, and the edible dormouse.[70]

The Cretan shrew, a type of white-toothed shrew is considered endemic to the island of Crete because this species of shrew is unknown elsewhere. It is a relic species of the crocidura shrews of which fossils have been found that can be dated to the Pleistocene era. In the present day it can only be found in the highlands of Crete.[71] It is considered to be the only surviving remnant of the endemic species of the Pleistocene Mediterranean islands.[72]

Bat species include: Blasius's horseshoe bat, the lesser horseshoe bat, the greater horseshoe bat, the lesser mouse-eared bat, Geoffroy's bat, the whiskered bat, Kuhl's pipistrelle, the common pipistrelle, Savi's pipistrelle, the serotine bat, the long-eared bat, Schreibers' bat and the European free-tailed bat.[73]

The Kri-kri (the Cretan ibex) lives in protected natural parks at the gorge of Samaria and the island of Agios Theodoros.

The Kri-kri (the Cretan ibex) lives in protected natural parks at the gorge of Samaria and the island of Agios Theodoros. Male Cretan ibex

Male Cretan ibex Cretan Hound or Kritikos Lagonikos, one of Europe's oldest hunting dog breeds

Cretan Hound or Kritikos Lagonikos, one of Europe's oldest hunting dog breeds

Birds

A large variety of birds includes eagles (can be seen in Lasithi), swallows (throughout Crete in the summer and all the year in the south of the island), pelicans (along the coast), and common cranes (including Gavdos and Gavdopoula). The Cretan mountains and gorges are refuges for the endangered lammergeier vulture. Bird species include: the golden eagle, Bonelli's eagle, the bearded vulture or lammergeier, the griffon vulture, Eleanora's falcon, peregrine falcon, lanner falcon, European kestrel, tawny owl, little owl, hooded crow, alpine chough, red-billed chough, and the Eurasian hoopoe.[74][75]

Reptiles and amphibians

Tortoises can be seen throughout the island. Snakes can be found hiding under rocks. Toads and frogs reveal themselves when it rains.

Reptiles include the Aegean wall lizard, Balkan green lizard, common chameleon, ocellated skink, snake-eyed skink, moorish gecko, Turkish gecko, Kotschy's gecko, spur-thighed tortoise, and the Caspian turtle.[73][76]

There are four species of snake on the island and these are not dangerous to humans. The four species include the leopard snake (locally known as Ochendra), the Balkan whip snake (locally called Dendrogallia), the dice snake (called Nerofido in Greek), and the only venomous snake is the nocturnal cat snake which has evolved to deliver a weak venom at the back of its mouth to paralyse geckos and small lizards, and is not dangerous to humans.[73][77]

Sea turtles include the green turtle and the loggerhead turtle which are both threatened species.[76] The loggerhead turtle nests and hatches on north-coast beaches around Rethymno and Chania, and south-coast beaches along the gulf of Mesara.[78]

Amphibians include the European green toad, American bullfrog (introduced), European tree frog, and the Cretan marsh frog (endemic).[73][76][79]

Arthropods

Crete has an unusual variety of insects. Cicadas, known locally as Tzitzikia, make a distinctive repetitive tzi tzi sound that becomes louder and more frequent on hot summer days. Butterfly species include the swallowtail butterfly.[73] Moth species include the hummingbird moth.[80] There are several species of scorpion such as Euscorpius carpathicus whose venom is generally no more potent than a mosquito bite.

Crustaceans and molluscs

River crabs include the semi-terrestrial Potamon potamios crab.[73] Edible snails are widespread and can cluster in the hundreds waiting for rainfall to reinvigorate them.

Sealife

Apart from terrestrial mammals, the seas around Crete are rich in large marine mammals, a fact unknown to most Greeks at present, although reported since ancient times. Indeed, the Minoan frescoes depicting dolphins in Queen's Megaron at Knossos indicate that Minoans were well aware of and celebrated these creatures. Apart from the famous endangered Mediterranean monk seal, which lives in almost all the coasts of the country, Greece hosts whales, sperm whales, dolphins and porpoises.[81] These are either permanent residents of the Mediterranean or just occasional visitors. The area south of Crete, known as the Greek Abyss, hosts many of them. Squid and octopus can be found along the coast and sea turtles and hammerhead sharks swim in the sea around the coast. The Cretaquarium and the Aquaworld Aquarium, are two of only three aquariums in the whole of Greece. They are located in Gournes and Hersonissos respectively. Examples of the local sealife can be seen there.[82][83]

Some of the fish that can be seen in the waters around Crete include: scorpion fish, dusky grouper, east Atlantic peacock wrasse, five-spotted wrasse, weever fish, common stingray, brown ray, mediterranean black goby, pearly razorfish, star-gazer, painted comber, damselfish, and the flying gurnard.[84]

The loggerhead sea turtle nests and hatches along the beaches of Rethymno and Chania and the gulf of Messara.

The loggerhead sea turtle nests and hatches along the beaches of Rethymno and Chania and the gulf of Messara.

Flora

The Minoans contributed to the deforestation of Crete. Further deforestation occurred in the 1600s "so that no more local supplies of firewood were available".[85]

Common wildflowers include: camomile, daisy, gladiolus, hyacinth, iris, poppy, cyclamen and tulip, among others.[86] There are more than 200 different species of wild orchid on the island and this includes 14 varieties of Ophrys cretica.[87] Crete has a rich variety of indigenous herbs including common sage, rosemary, thyme, and oregano.[87][88] Rare herbs include the endemic Cretan dittany.[87][88] and ironwort, Sideritis syriaca, known as Malotira (Μαλοτήρα). Varieties of cactus include the edible prickly pear. Common trees on the island include the chestnut, cypress, oak, olive tree, pine, plane, and tamarisk.[88] Trees tend to be taller to the west of the island where water is more abundant.

Snake lily (Dracunculus vulgaris)

Snake lily (Dracunculus vulgaris) The Ophrys cretica orchid.

The Ophrys cretica orchid.

Environmentally protected areas

There are a number of environmentally protected areas. One such area is located at the island of Elafonisi on the coast of southwestern Crete. Also, the palm forest of Vai in eastern Crete and the Dionysades (both in the municipality of Sitia, Lasithi), have diverse animal and plant life. Vai has a palm beach and is the largest natural palm forest in Europe. The island of Chrysi, 15 kilometres (9 miles) south of Ierapetra, has the largest naturally-grown Juniperus macrocarpa forest in Europe. Samaria Gorge is a World Biosphere Reserve and Richtis Gorge is protected for its landscape diversity.

Mythology

Crete has a strong association with Ancient Greek Gods but is also connected with the Minoan civilisation.

According to Greek Mythology, The Diktaean Cave at Mount Dikti was the birthplace of the god Zeus. The Paximadia islands were the birthplace of the goddess Artemis and the god Apollo. Their mother, the goddess Leto, was worshipped at Phaistos. The goddess Athena bathed in Lake Voulismeni. The ancient Greek god Zeus launched a lightning bolt at a giant lizard that was threatening Crete. The lizard immediately turned to stone and became the island of Dia. The island can be seen from Knossos and it has the shape of a giant lizard. The islets of Lefkai were the result of a musical contest between the Sirens and the Muses. The Muses were so anguished to have lost that they plucked the feathers from the wings of their rivals; the Sirens turned white and fell into the sea at Aptera ("featherless") where they formed the islands in the bay that were called Lefkai (the islands of Souda and Leon).[89] Heracles, in one of his labors, took the Cretan bull to the Peloponnese. Europa and Zeus made love at Gortys and conceived the kings of Crete: Rhadamanthys, Sarpedon, and Minos.

The labyrinth of the Palace of Knossos was the setting for the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur in which the Minotaur was slain by Theseus. Icarus and Daedalus were captives of King Minos and crafted wings to escape. After his death King Minos became a judge of the dead in Hades, while Rhadamanthys became the ruler of the Elysian fields.

Culture

Crete has its own distinctive Mantinades poetry. The island is known for its Mantinades-based music (typically performed with the Cretan lyra and the laouto) and has many indigenous dances, the most noted of which is the Pentozali. Since the 1980s and certainly in the 90s onwards there has been a proliferation of Cultural Associations that teach dancing (in Western Crete many focus on rizitiko singing). These Associations often perform in official events but also become stages for people to meet up and engage in traditionalist practices. The topic of tradition and the role of Cultural Associations in reviving it is very often debated throughout Crete.[90]

Cretan authors have made important contributions to Greek literature throughout the modern period; major names include Vikentios Kornaros, creator of the 17th-century epic romance Erotokritos (Greek Ερωτόκριτος), and, in the 20th century, Nikos Kazantzakis. In the Renaissance, Crete was the home of the Cretan School of icon painting, which influenced El Greco and through him subsequent European painting. Crete is also famous for its traditional cuisine. The nutritional value of the Cretan cuisine was discovered by the American epidemiologist Ancel Keys in the 1960, being later often mentioned by epidemiologists as one of the best examples of the Mediterranean diet.[91]

Cretans are fiercely proud of their island and customs, and men often don elements of traditional dress in everyday life: knee-high black riding boots (stivania), vráka breeches tucked into the boots at the knee, black shirt and black headdress consisting of a fishnet-weave kerchief worn wrapped around the head or draped on the shoulders (sariki). Men often grow large mustaches as a mark of masculinity.

Cretan society is known in Greece and internationally for family and clan vendettas which persist on the island to date.[92][93] Cretans also have a tradition of keeping firearms at home, a tradition lasting from the era of resistance against the Ottoman Empire. Nearly every rural household on Crete has at least one unregistered gun.[92] Guns are subject to strict regulation from the Greek government, and in recent years a great deal of effort to control firearms in Crete has been undertaken by the Greek police, but with limited success.

Dancers from Sfakia.

Dancers from Sfakia. Old man from Crete dressed in the typical black shirt.

Old man from Crete dressed in the typical black shirt. Dakos, traditional Cretan salad.

Dakos, traditional Cretan salad.

Sports

Crete has many football clubs playing in the local leagues. During the 2011–12 season, OFI Crete, which plays at Theodoros Vardinogiannis Stadium (Iraklion), and Ergotelis F.C., which plays at the Pankritio Stadium (Iraklion) were both members of the Greek Superleague. During the 2012–13 season, OFI Crete, which plays at Theodoros Vardinogiannis Stadium (Iraklion), and Platanias F.C., which plays at the Perivolia Municipal Stadium, near Chania, are both members of the Greek Superleague.

Notable people

Notable people from Crete include:

- Nikos Kazantzakis, author, born in Heraklion, 7 times suggested for the Nobel Prize

- Odysseas Elytis, poet, awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1979, born in Heraklion[94]

- Georgios Chortatzis, Renaissance author

- Vitsentzos Kornaros, Renaissance author from Sitia, who lived in Heraklion (then Candia)

- Domenikos Theotokopoulos (El Greco), Renaissance artist, born in Heraklion

- Nikos Xilouris, famous composer and singer.

- Psarantonis, Cretan folk singer and Cretan lyra player and brother of Nikos Xilouris.

- Nana Mouskouri, singer, born in Chania

- Eleftherios Venizelos, former Greek Prime Minister, born in Chania Prefecture

- Konstantinos Mitsotakis, nephew of Eleftherios Venizelos and Prime Minister of Greece.

- Daskalogiannis, leader of the Orlov Revolt in Crete in 1770

- Michalis Kourmoulis, leader of the Greek War of Independence from Messara.

- Eleni Daniilidou, tennis player, born in Chania

- Louis Tikas, Greek-American labor union leader

- Tess Fragoulis, Greek-Canadian writer, born in Heraklion

- Nick Dandolos, a.k.a. Nick the Greek, professional gambler and high roller

- Joseph Sifakis, a computer scientist, laureate of the 2007 Turing Award, born in Heraklion in 1946

- Constantinos Daskalakis, Associate Professor at MIT's Electrical Engineering and Computer Science department.

- George Karniadakis, Professor of Applied Mathematics at Brown University; also Research Scientist at MIT

- John Aniston (Giannis Anastasakis), Greek-American actor, father of Jennifer Aniston

- George Psychoundakis, a shepherd, a war hero and an author.

- Ahmed Resmî Efendi: 18th-century Ottoman statesman, diplomat and author (notably of two sefâretnâme). Turkey's first ever ambassador in Berlin[95] (during Frederick the Great's reign). He was born into a Muslim family of Greek descent in the Cretan town of Rethymno in the year 1700.[96][97][98][99]

- Giritli Ali Aziz Efendi: Turkey's third ambassador in Berlin and arguably the first Turkish author to have written in novelistic form.

- Al-Husayn I ibn Ali at-Turki – founder of the Husainid Dynasty, which ruled Tunisia until 1957.

- Salacıoğlu (1750 Hanya – 1825 Kandiye): One of the most important 18th-century poets of Turkish folk literature.

- Giritli Sırrı Pasha: Ottoman administrator, Leyla Saz's husband and a notable man of letters in his own right.

- Vedat Tek: Representative figure of the First National Architecture Movement in Turkish architecture, son of Leyla Saz and Giritli Sırrı Pasha.

- Paul Mulla (alias Mollazade Mehmed Ali): born Muslim, converted to Christianity and becoming a Roman Catholic bishop and author.

- Rahmizâde Bahaeddin Bediz: The first Turkish photographer by profession. The thousands of photographs he took, based as of 1895 successively in Crete, İzmir, İstanbul and Ankara (as Head of the Photography Department of Turkish Historical Society), have immense historical value.

- Salih Zeki: Turkish photographer in Chania[100]

- Ali Nayip Zade: Associate of Eleftherios Venizelos, Prefect of Drama and Kavala, Adrianople, and Lasithi.

- Ismail Fazil Pasha: (1856–1921) descended from the rooted Cebecioğlu family of Söke who had settled in Crete.[101] He has been the first Minister of Public Works in the government of Grand National Assembly in 1920. He was the father of Ali Fuad and Mehmed Ali.

- Mehmet Atıf Ateşdağlı: (1876–1947) Turkish officer.

- Mustafa Ertuğrul Aker: (1892–1961) Turkish officer who sank HMS Ben-my-Chree.

- Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı, alias Halikarnas Balıkçısı (The Fisherman of Halicarnassus), writer, although born in Crete and has often let himself be cited as Cretan, descends from a family of Ottoman aristocracy with roots in Afyonkarahisar. His father had been an Ottoman High Commissioner in Crete and later ambassador in Athens. *Likewise, as stated above, Mustafa Naili Pasha was Albanian/Egyptian.[102]

- Bülent Arınç (born. 25 May 1948) has been a Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey since 2009. He is of Cretan Muslim heritage with his ancestors arriving to Turkey as Cretan refugees during the population exchange between Greece and Turkey at the time of Sultan Abdul Hamid II[103] and is fluent in Cretan Greek.[104] Arınç is a proponent of wanting to reconvert the Hagia Sophia into a mosque, which has caused diplomatic protestations from Greece.[105]

- Yoseph Shlomo Delmedigo, renaissance rabbi, mathematician, astronomer and philosopher.

- Zach Galifianakis paternal grandparents, Mike Galifianakis and Sophia Kastrinakis, were from Crete.

See also

References

- https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=urb_lpop1&lang=en

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Ancient Crete Oxford Bibliographies Online: Classics

- Stephanie Lynn Budin, The Ancient Greeks: An Introduction (New York: Oxford UP, 2004), 42.

- O. Dickinson, The Aegean Bronze Age (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 1994), 241–244.

- Found on the PY An 128 tablet.

- Found on the PY Ta 641 and PY Ta 709 tablets.

- "The Linear B word ke-re-si-ji". Palaeolexicon. Word-study tool for ancient languages.

- Κρής, Κρήσιος s.v. κρησίαι. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Book 14, line 199; Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- Kalantzis, Konstantinos (2019). Tradition in the Frame: Photography, Power, and Imagination in Sfakia, Crete. Indiana University Press. pp. 23–58. ISBN 978-0-253-03713-8.

- "Gorge of the Dead". Cretanbeaches.com. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- "Richtis gorge". Cretanbeaches.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- "Richtis beach and gorge". Candia.wordpress.com. 20 April 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- "Richtis gorge and waterfall". Worldreviewer.com. 25 February 2011. Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- Photos of Agia Lake Crete TOURnet.

- Lake Voulismeni Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine aghiosnikolaos.eu

- Rackham, O. & Moody, J., 1996. The Making of the Cretan Landscape, Manchester University Press, https://books.google.com/books?id=k4dHmA9jq4wC&printsec=frontcover&dq=cretan+landscape&source=bl&ots=Getzm4MGUe&sig=zmyzZT89lwQXQeVPZP9_dXXzxG0&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RQFwUNSFJMLQtAbS1oGQCg&redir_esc=y

- Panagos, Panagos; Christos, Karydas; Cristiano, Ballabio; Ioannis, Gitas (2014). "Seasonal monitoring of soil erosion at regional scale: An application of the G2 model in Crete focusing on agricultural land uses". International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation. 27: 147–155. Bibcode:2014IJAEO..27..147P. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2013.09.012.

- Crete, p.44, by Victoria Kyriakopoulos.

- "Demographic and social characteristics of the Resident Population of Greece according to the 2011 Population – Housing Census revision of 20/3/2014" (PDF). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 12 September 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2015.

- Π.Δ. 51/87 "Καθορισμός των Περιφερειών της Χώρας για το σχεδιασμό κ.λ.π. της Περιφερειακής Ανάπτυξης" (Determination of the Regions of the Country for the planning etc. of the development of the Region, ΦΕΚ A 26/06.03.1987

- 2001 Census

- The rough guide to Crete, Introduction, p. ix by J. Fisher and G. Garvey.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- "New road in Crete set to improve journey times and safety-Projects". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Parthenidis`, Kyrillos (4 April 2020). "New road in Crete set to improve journey times and safety-Projects". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Rackham, O. & Moody, J., 1996. The Making of the Cretan Landscape, Manchester University Press,

- ΤΟΠΙΟ: Αγνωστα Βιομηχανικά Μνημεία Ι: υπολείμματα του βιομηχανικού σιδηροδρόμου Ηρακλείου http://to-pio.blogspot.gr/2011/11/blog-post_17.html

- No Container Transshipment Hub in Timbaki Archived 23 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- "EuroAsia Interconnector Project and Progress" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- "EuroAfrica Interconnector". Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Η ηλεκτρική διασύνδεση EuroAsia Interconnector θα εξασφαλίσει ενεργειακά την Κρήτη". Cretalive. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Chung, Emily. "One hell of an impression". CBCnews. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "Strasser F. Thomas et al. (2010) Stone Age seafaring in the Mediterranean, Hesperia (The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens), vol. 79, pp. 145–190". Scribd.com. 15 December 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- Wilford, J.N., On Crete, New Evidence of Very Ancient Mariners The New York Times, 15 February 2010.

- Bowner, B., Hominids Went Out of Africa on Rafts Wired, 8 January 2010.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2007 Knossos fieldnotes The Modern Antiquarian

- Shelmerdine, Cynthia. "Where Do We Go From Here? And How Can the Linear B Tablets Help Us Get There?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- Jane Francis and Anna Kouremenos (2016). Roman Crete: New Perspectives. Oxford: Oxbow. ISBN 978-1785700958.

- Kazhdan (1991), p. 546

- Reinhart Dozy, Histoire des Musulmans d'Espagne: jusqu'à la conquête de l'Andalousie par les Almoravides (French) pg. 711–1110, Leiden, 1861 & 1881, 2nd edition

- Panagiotakis, Introduction, p. XVI.

- ODB, "Crete" (T. E. Gregory, A. Kazhdan), pp. 545–546.

- Treadgold 1997, p. 495.

- Tiepolo, Maria Francesca; Tonetti, Eurigio (2002). I greci a Venezia. Istituto veneto di scienze. p. 201. ISBN 978-88-88143-07-1.

Cretese Nikolaos Kalliakis

- Boehm, Eric H. (1995). Historical abstracts: Modern history abstracts, 1450–1914, Volume 46, Issues 3–4. American Bibliographical Center of ABC-Clio. p. 755. OCLC 701679973.

Between the 15th and 19th centuries the University of Padua attracted a great number of Greek students who wanted to study medicine. They came not only from Venetian dominions (where the percentage reaches 97% of the students of Italian universities) but also from Turkish-occupied territories of Greece. Several professors of the School of Medicine and Philosophy were Greeks, including Giovanni Cottunio, Niccolò Calliachi, Giorgio Calafatti...

- Convegno internazionale nuove idee e nuova arte nell '700 italiano, Roma, 19–23 maggio 1975. Accademia nazionale dei Lincei. 1977. p. 429. OCLC 4666566.

Nicolò Duodo riuniva alcuni pensatori ai quali Andrea Musalo, oriundo greco, professore di matematica e dilettante di architettura chiariva le nuove idée nella storia dell’arte.

- M. Greene. 2001. Ruling an island without a navy: A comparative view of Venetian and Ottoman Crete. Oriente moderno, 20(81), 193–207

- A.J. Schoenfeld. 2007. Immigration and Assimilation in the Jewish Community of Late Venetian Crete (15th–17th centuries). Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 25(1), 1–15

- Starr, J. (1942), Jewish Life in Crete Under the Rule of Venice, Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol. 12, pp. 59–114.

- Carlo Capra; Franco Della Peruta; Fernando Mazzocca (2002). Napoleone e la repubblica italiana: 1802–1805. Skira. p. 200. ISBN 978-88-8491-415-6.

Simone Stratico, nato a Zara nel 1733 da famiglia originaria di Creta (abbandonata a seguito della conquista turca del 1669)

- Demetres Tziovas, Greece and the Balkans: Identities, Perceptions and Cultural Encounters Since the Enlightenment; William Yale, The Near East: A modern history Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1958)

- William Yale, The Near East: A modern history by (Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Press, 1958)

- "Vakantie Kreta – De beste Tips & Reviews | Holidaytrust.nl" (in Dutch). Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Pinar Senisik, The Transformation of Ottoman Crete, Revolts, Politics and Identity in the Late Nineteenth century p. 165. I. B. Tauris, 2011.

- Robert Holland and Diane Markides, The British and the Hellenes: Struggles for Mastery in the Eastern Mediterranean 1850–1960. p. 81. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- "Some Noteworthy War Criminals" Archived 1 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Source: History of the United Nations War Crimes Commission and the Development of the Laws of War, United Nations War Crimes Commission. London: HMSO, 1948, p. 526, updated 29 January 2007 by Stuart Stein (University of the West of England), accessed 22 January 2010

- Charter flights to Sitia in 2012 Archived 1 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- KTEL bus services

- On the Rights of Citizens of the Union, EC Directive 2004/58 EC (2004) Eur-lex.europa.eu

- Archaeological sites and Museums in Crete ExploreCrete.com

- Van der Geer, A.A.E., Dermitzakis, M., De Vos, J., 2006. Crete before the Cretans: the reign of dwarfs. Pharos 13, 121–132. Athens: Netherlands Institute.PDF

- Crete: 10 Fun Facts and Interesting Insights

- Αναρτήθηκε από admin. "ΤΟΠΙΟ: Θοδωρού, η άγνωστη νησίδα του Βενετικού ναυτικού οχυρού, των κρι-κρι και η απαγόρευση προσέγγισης". To-pio.blogspot.gr. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Thodorou Islands off Platanias ExploreCrete.com

- Cretan Ibex, by Alexandros Roniotis CretanBeaches.com

- Cretan wildcat Archived 11 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine CretanBeaches.com

- Cretan spiny mouse CretanBeaches.com

- Terrestrial mammals of Crete CretanBeaches.com

- Atlas of terrestrial mammals of the Ionian and Aegean islands. De Gruyter. 30 October 2012. p. 43. ISBN 9783110254587.

- Evolution of Island Mammals. Wiley. 14 February 2011. p. 35. ISBN 9781444391282.

- Wildlife on Crete IntoCrete.com

- Birds of Crete We-love-crete.com

- Checklist and Guide to the Birds of Crete Archived 29 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Cretewww.com

- Native Reptiles of Crete at Aquaworld Aquaworld Aquarium.

- The Snakes of Crete by John McClaren CreteGazette.com

- Crete p. 69, by Victoria Kyriakopoulos

- Dufresnes, C. (2019). Amphibians of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East: A Photographic Guide. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-4137-4.

- Feeding time for a hummingbird moth Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine PictureNation.co.uk

- Marine mammals of Crete Archived 7 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine CretanBeaches.com

- Cretaquarium Archived 26 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Cretaquarium.gr

- Great Britons in Crete, John Bryce McLaren Archived 19 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine BritsinCrete.net

- Fish from Crete at Aquaworld Aquaworld Aquarium

- Sands, Roger (2005). Forestry in a Global Context. p. 27. ISBN 9780851990897. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Fielding, J. and Turland, N. "Flowers of Crete", Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, ISBN 978-1842460795, 2008

- Crete p.68 by Victoria Kyriakopoulos

- The Flora of Crete ExploreCrete.com

- Caroline M. Galt, "A marble fragment at Mount Holyoke College from the Cretan city of Aptera", Art and Archaeology 6 (1920:150).

- Kalantzis, Konstantinos (2019). Tradition in the Frame Photography, Power, and Imagination in Sfakia, Crete. Indiana University Press. pp. 153–178. ISBN 978-0-253-03713-8.

- António José Marques da Silva, La diète méditerranéenne. Discours et pratiques alimentaires en Méditerranée (vol. 2), L'Harmattan, Paris, 2015 ISBN 978-2-343-06151-1, pp. 49–51

- Brian Murphy: Vendetta Victims: People, A Village – Crete's `Cycle Of Blood' Survives The Centuries at The Seattle Times, 14 January 1999.

- Aris Tsantiropoulos: "Collective Memory and Blood Feud: The Case of Mountainous Crete" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012. (254 KB), Crimes and Misdemeanours 2/1 (2008), University of Crete.

- Odysseas Elytis by Alexandros Roniotis, CretanBeaches.com.

- "Tuerkische Botschafter in Berlin" (in German). Turkish Embassy, Berlin. Archived from the original on 2 June 2001.

- Houtsma, Martinus T. (1987). E. J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913 – 1936, Volume 9. Brill. p. 1145. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

RESMI, AHMAD Ottoman statesman and historian. Ahmad b. Ibrahim, known as Resmi, belonged to Rethymo (turk. Resmo; hence his epithet) in Crete and was of Greek descent (cf. J. v. Hammer, GOR, viii. 202). He was born in III (1700) and came in 1146 (1733) to Stambul where he was educated, married a daughter of the Ke is Efendi

- Müller-Bahlke, Thomas J. (2003). Zeichen und Wunder: Geheimnisse des Schriftenschranks in der Kunst- und Naturalienkammer der Franckeschen Stiftungen : kulturhistorische und philologische Untersuchungen. Franckesche Stiftungen. p. 58. ISBN 978-3-931479-46-6.

Ahmed Resmi Efendi (1700–1783). Der osmanische Staatsmann und Geschichtsschreiber griechischer Herkunft. Translation "Ahmed Resmi Efendi (1700–1783). The Ottoman statesman and historian of Greek origin"

- European studies review (1977). European studies review, Volumes 7–8. Sage Publications. p. 170.

Resmi Ahmad (−83) was originally of Greek descent. He entered Ottoman service in 1733 and after holding a number of posts in local administration, was sent on missions to Vienna (1758) and Berlin (1763–4). He later held a number of important offices in central government. In addition, Resmi Ahmad was a contemporary historian of some distinction.

- Sir Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb (1954). Encyclopedia of Islam. Brill. p. 294. ISBN 90-04-16121-X.

Ahmad b. Ibrahim, known as Resmi came from Rethymno (Turk. Resmo; hence his epithet?) in Crete and was of Greek descent (cf. Hammer- Purgstall, viii, 202). He was born in 1112/ 1700 and came in 1 146/1733 to Istanbul,

- "Salih Zeki". Anopolis72000.blogspot.com.

- "Interview with Ayşe Cebesoy Sarıalp, Ali Fuat Pasha's niece". Aksiyon.com.tr. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011.

- Yeni Giritliler Archived 19 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine Article on the rising interest in Cretan heritage (in Turkish)

- "Arınç Ahmediye köyünde çocuklarla Rumca konuştu" [Arınç spoke Greek with the children in the village of Ahmediye]. Milliyet (in Turkish). Turkey. 23 September 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- Bülent Arınç anadili Rumca konuşurken [Bülent Arınç talking to native speakers of Greek] (video) (in Turkish and Greek). You Tube. 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- "Greece angered over Turkish Deputy PM's Hagia Sophia remarks". Hurriyet Daily News. Turkey. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

Sources

- Panagiotakis, Nikolaos M., ed. (1987). "Εισαγωγικό Σημείωμα ("Introduction")". Crete, History and Civilization (in Greek). I. Vikelea Library, Association of Regional Associations of Regional Municipalities. pp. XI–XX.

- Francis, Jane and Anna Kouremenos (eds.) 2016. Roman Crete: New Perspectives. Oxford: Oxbow.

External links

- Official website

- Natural History Museum of Crete at the University of Crete.

- Cretaquarium Thalassocosmos in Heraklion.

- Aquaworld Aquarium in Hersonissos.

- Ancient Crete at Oxford Bibliographies Online: Classics.

- Official Greek National Tourism Organisation website

- Interactive Virtual Tour of Crete