Heracles

Heracles (/ˈhɛrəkliːz/ HERR-ə-kleez; Greek: Ἡρακλῆς, Hēraklês, Glory/Pride of Hēra, "Hera"), born Alcaeus[1] (Ἀλκαῖος, Alkaios) (/ælˈsiːəs/) or Alcides[2] (Ἀλκείδης, Alkeidēs) (/ælˈsaɪdiːz/) was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, foster son of Amphitryon.[3] He was a great-grandson and half-brother (as they are both sired by the god Zeus) of Perseus. He was the greatest of the Greek heroes, a paragon of masculinity, the ancestor of royal clans who claimed to be Heracleidae (Ἡρακλεῖδαι), and a champion of the Olympian order against chthonic monsters. In Rome and the modern West, he is known as Hercules, with whom the later Roman emperors, in particular Commodus and Maximian, often identified themselves. The Romans adopted the Greek version of his life and works essentially unchanged, but added anecdotal detail of their own, some of it linking the hero with the geography of the Central Mediterranean. Details of his cult were adapted to Rome as well.

| Heracles | |

|---|---|

Divine protector of mankind, patron of gymnasium | |

One of the most famous depictions of Heracles, Farnese Hercules, Roman marble statue on the basis of an original by Lysippos, 216 CE. National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy | |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Symbol | Club, lion skin |

| Personal information | |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| Parents | Zeus and Alcmene |

| Siblings | Aeacus, Angelos, Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Consort | Megara, Omphale, Deianira, Hebe |

| Children | Alexiares and Anicetus, Telephus, Hyllus, Tlepolemus |

| Roman equivalent | Hercules |

| Etruscan equivalent | Hercle |

| Greek mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

|

|

|

Origin

Many popular stories were told of his life, the most famous being The Twelve Labours of Heracles; Alexandrian poets of the Hellenistic age drew his mythology into a high poetic and tragic atmosphere.[4] His figure, which initially drew on Near Eastern motifs such as the lion-fight, was widely known.

Heracles was the greatest of Hellenic chthonic heroes, but unlike other Greek heroes, no tomb was identified as his. Heracles was both hero and god, as Pindar says heros theos; at the same festival sacrifice was made to him, first as a hero, with a chthonic libation, and then as a god, upon an altar: thus he embodies the closest Greek approach to a "demi-god".[4]

The core of the story of Heracles has been identified by Walter Burkert as originating in Neolithic hunter culture and traditions of shamanistic crossings into the netherworld.[5] It is possible that the myths surrounding Heracles were based on the life of a real person or several people whose accomplishments became exaggerated with time.[6] Based on commonalities in the legends of Heracles and Odysseus, author Steven Sora suggested that they were both based on the same historical person, who made his mark prior to recorded history.[7]

Hero or god

Heracles' role as a culture hero, whose death could be a subject of mythic telling (see below), was accepted into the Olympian Pantheon during Classical times. This created an awkwardness in the encounter with Odysseus in the episode of Odyssey XI, called the Nekuia, where Odysseus encounters Heracles in Hades:

And next I caught a glimpse of powerful Heracles—

His ghost I mean: the man himself delights

in the grand feasts of the deathless gods on high ...

Around him cries of the dead rang out like cries of birds

scattering left and right in horror as on he came like night ...[8]

Ancient critics were aware of the problem of the aside that interrupts the vivid and complete description, in which Heracles recognizes Odysseus and hails him, and modern critics find very good reasons for denying that the verse's beginning, in Fagles' translation His ghost I mean ... were part of the original composition: "once people knew of Heracles' admission to Olympus, they would not tolerate his presence in the underworld", remarks Friedrich Solmsen,[9] noting that the interpolated verses represent a compromise between conflicting representations of Heracles.

Christian chronology

In Christian circles, a Euhemerist reading of the widespread Heracles cult was attributed to a historical figure who had been offered cult status after his death. Thus Eusebius, Preparation of the Gospel (10.12), reported that Clement could offer historical dates for Hercules as a king in Argos: "from the reign of Hercules in Argos to the deification of Hercules himself and of Asclepius there are comprised thirty-eight years, according to Apollodorus the chronicler: and from that point to the deification of Castor and Pollux fifty-three years: and somewhere about this time was the capture of Troy."

Readers with a literalist bent, following Clement's reasoning, have asserted from this remark that, since Heracles ruled over Tiryns in Argos at the same time that Eurystheus ruled over Mycenae, and since at about this time Linus was Heracles' teacher, one can conclude, based on Jerome's date—in his universal history, his Chronicon—given to Linus' notoriety in teaching Heracles in 1264 BCE, that Heracles' death and deification occurred 38 years later, in approximately 1226 BCE.

Cult

The ancient Greeks celebrated the festival of the Heracleia, which commemorated the death of Heracles, on the second day of the month of Metageitnion (which would fall in late July or early August). What is believed to be an Egyptian Temple of Heracles in the Bahariya Oasis dates to 21 BCE. A reassessment of Ptolemy's descriptions of the island of Malta attempted to link the site at Ras ir-Raħeb with a temple to Heracles,[10] but the arguments are not conclusive.[11] Several ancient cities were named Heraclea in his honor.

Although the Athenians were among the first to worship Heracles as a god, there were Greek cities that refused to recognize the hero's divine status. There are also several poleis that merely provided two separate sanctuaries for Heracles, one recognizing him as a god, the other only as a hero.[12] This ambiguity helped create the Heracles cult especially when historians (e.g. Herodotus) and artists encouraged worship such as the painters during the time of the Peisistratos, who often presented Heracles entering Olympus in their works.[12]

Some sources explained that the cult of Heracles persisted because of the hero's ascent to heaven and his suffering, which became the basis for festivals, ritual, rites, and the organization of mysteries.[13] There is the observation, for example, that sufferings (pathea) gave rise to the rituals of grief and mourning, which came before the joy in the mysteries in the sequence of cult rituals.[13] Also, like the case of Apollo, the cult of Hercules has been sustained through the years by absorbing local cult figures such as those who share the same nature.[14] He was also constantly invoked as a patron for men, especially the young ones. For example, he was considered the ideal in warfare so he presided over gymnasiums and the ephebes or those men undergoing military training.[14]

There were ancient towns and cities that also adopted Heracles as a patron deity, contributing to the spread of his cult. There was the case of the royal house of Macedonia, which claimed lineal descent from the hero[15] primarily for purposes of divine protection and legitimator of actions.

The earliest evidence that show the worship of Heracles in popular cult was in 6th century BCE (121–122 and 160–165) via an ancient inscription from Phaleron.[14]

Character

Extraordinary strength, courage, ingenuity, and sexual prowess with both males and females were among the characteristics commonly attributed to him. Heracles used his wits on several occasions when his strength did not suffice, such as when laboring for the king Augeas of Elis, wrestling the giant Antaeus, or tricking Atlas into taking the sky back onto his shoulders. Together with Hermes he was the patron and protector of gymnasia and palaestrae.[16] His iconographic attributes are the lion skin and the club. These qualities did not prevent him from being regarded as a playful figure who used games to relax from his labors and played a great deal with children.[17] By conquering dangerous archaic forces he is said to have "made the world safe for mankind" and to be its benefactor.[18] Heracles was an extremely passionate and emotional individual, capable of doing both great deeds for his friends (such as wrestling with Thanatos on behalf of Prince Admetus, who had regaled Heracles with his hospitality, or restoring his friend Tyndareus to the throne of Sparta after he was overthrown) and being a terrible enemy who would wreak horrible vengeance on those who crossed him, as Augeas, Neleus, and Laomedon all found out to their cost. There was also a coldness to his character, which was demonstrated by Sophocles' depiction of the hero in The Trachiniae. Heracles threatened his marriage with his desire to bring two women under the same roof; one of them was his wife Deianeira.[19]

In the works of Euripides involving Heracles, his actions were partly driven by forces outside rational human control. By highlighting the divine causation of his madness, Euripides problematized Heracles' character and status within the civilized context.[20] This aspect is also highlighted in Hercules Furens where Seneca linked the hero's madness to an illusion and a consequence of Herakles' refusal to live a simple life, as offered by Amphitryon. It was indicated that he preferred the extravagant violence of the heroic life and that its ghosts eventually manifested in his madness and that the hallucinatory visions defined Herakles' character.[21]

Mythology

Birth and childhood

A major factor in the well-known tragedies surrounding Heracles is the hatred that the goddess Hera, wife of Zeus, had for him. A full account of Heracles must render it clear why Heracles was so tormented by Hera, when there were many illegitimate offspring sired by Zeus. Heracles was the son of the affair Zeus had with the mortal woman Alcmene. Zeus made love to her after disguising himself as her husband, Amphitryon, home early from war (Amphitryon did return later the same night, and Alcmene became pregnant with his son at the same time, a case of heteropaternal superfecundation, where a woman carries twins sired by different fathers).[22] Thus, Heracles' very existence proved at least one of Zeus' many illicit affairs, and Hera often conspired against Zeus' mortal offspring as revenge for her husband's infidelities. His twin mortal brother, son of Amphitryon, was Iphicles, father of Heracles' charioteer Iolaus.

On the night the twins Heracles and Iphicles were to be born, Hera, knowing of her husband Zeus' adultery, persuaded Zeus to swear an oath that the child born that night to a member of the House of Perseus would become High King. Hera did this knowing that while Heracles was to be born a descendant of Perseus, so too was Eurystheus. Once the oath was sworn, Hera hurried to Alcmene's dwelling and slowed the birth of the twins Heracles and Iphicles by forcing Ilithyia, goddess of childbirth, to sit crosslegged with her clothing tied in knots, thereby causing the twins to be trapped in the womb. Meanwhile, Hera caused Eurystheus to be born prematurely, making him High King in place of Heracles. She would have permanently delayed Heracles' birth had she not been fooled by Galanthis, Alcmene's servant, who lied to Ilithyia, saying that Alcmene had already delivered the baby. Upon hearing this, she jumped in surprise, loosing the knots and inadvertently allowing Alcmene to give birth to Heracles and Iphicles.

Fear of Hera's revenge led Alcmene to expose the infant Heracles, but he was taken up and brought to Hera by his half-sister Athena, who played an important role as protectress of heroes. Hera did not recognize Heracles and nursed him out of pity. Heracles suckled so strongly that he caused Hera pain, and she pushed him away. Her milk sprayed across the heavens and there formed the Milky Way. But with divine milk, Heracles had acquired supernatural powers. Athena brought the infant back to his mother, and he was subsequently raised by his parents.[23]

The child was originally given the name Alcides by his parents; it was only later that he became known as Heracles.[3] He was renamed Heracles in an unsuccessful attempt to mollify Hera. He and his twin were just eight months old when Hera sent two giant snakes into the children's chamber. Iphicles cried from fear, but his brother grabbed a snake in each hand and strangled them. He was found by his nurse playing with them on his cot as if they were toys. Astonished, Amphitryon sent for the seer Tiresias, who prophesied an unusual future for the boy, saying he would vanquish numerous monsters.

Youth

After killing his music tutor Linus with a lyre, he was sent to tend cattle on a mountain by his foster father Amphitryon. Here, according to an allegorical parable, "The Choice of Heracles", invented by the sophist Prodicus (c. 400 BCE) and reported in Xenophon's Memorabilia 2.1.21–34, he was visited by two allegorical figures—Vice and Virtue—who offered him a choice between a pleasant and easy life or a severe but glorious life: he chose the latter. This was part of a pattern of "ethicizing" Heracles over the 5th century BCE.[24]

Later in Thebes, Heracles married King Creon's daughter, Megara. In a fit of madness, induced by Hera, Heracles killed his children and Megara. After his madness had been cured with hellebore by Antikyreus, the founder of Antikyra,[25] he realized what he had done and fled to the Oracle of Delphi. Unbeknownst to him, the Oracle was guided by Hera. He was directed to serve King Eurystheus for ten years and perform any task Eurystheus required of him. Eurystheus decided to give Heracles ten labours, but after completing them, Heracles was cheated by Eurystheus when he added two more, resulting in the Twelve Labors of Heracles.

Labours of Heracles

Driven mad by Hera, Heracles slew his own children. To expiate the crime, Heracles was required to carry out ten labours set by his archenemy, Eurystheus, who had become king in Heracles' place. If he succeeded, he would be purified of his sin and, as myth says, he would become a god, and be granted immortality.

"Other traditions place Heracles' madness at a later time, and relate the circumstances differently."[26] In some traditions there was only a divine reason for Heracles twelve labours: " Zeus, in his desire not to leave Heracles the victim of Hera's jealousy, made her promise, that if Heracles executed twelve great works in the service of Eurystheus, he should become immortal."[26] In the play "Heracles Mad" by Euripides , Heracles is driven to madness by Hera and kills his children after his twelve labours.

Despite the difficulty, Heracles accomplished these tasks, but Eurystheus in the end did not accept the success the hero had with two of the labours: the cleansing of the Augean stables, because Heracles was going to accept pay for the labour; and the killing of the Lernaean Hydra, as Heracles' nephew, Iolaus, had helped him burn the stumps of the multiplying heads.

Eurystheus set two more tasks, fetching the Golden Apples of Hesperides and capturing Cerberus. In the end, with ease, the hero successfully performed each added task, bringing the total number of labours up to the magic number twelve.

Not all versions and writers give the labours in the same order. The Bibliotheca (2.5.1–2.5.12) gives the following order:

- 1. Slay the Nemean Lion

- Heracles defeated a lion that was attacking the city of Nemea with his bare hands. After he succeeded he wore the skin as a cloak to demonstrate his power over the opponent he had defeated.

- 2. Slay the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra

- a fire-breathing monster with multiple serpent heads that when one head was cut off, two would grow in its place. It lived in a swamp near Lerna. Hera had sent it in hope it would destroy Heracles' home city because she thought it was invincible. With help from his nephew Iolaus, he defeated the monster and dipped his arrows in its poisoned blood, thus envenomizing them.

- 3. Capture the Golden Hind of Artemis

- not to kill, but to catch, this monster. A different, but still difficult, task for a hero. It cost time but, having chased it for a year, Heracles wore out the Hind and presented it alive to Eurystheus.

- 4. Capture the Erymanthian Boar

- a fearsome marauding boar on the loose. Eurystheus set Heracles the Labour of catching it, and bringing it to Mycenae. Again, a time-consuming task, but the tireless hero found the beast, captured it, and brought it to its final spot. Patience is the heroic quality in the third and fourth Labours.

- 5. Clean the Augean stables in a single day

- the Augean stables were the home of 3,000 cattle with poisoned faeces which Augeas had been given by his father Helios. Heracles was given the near impossible task of cleaning the stables of the diseased faeces. He accomplished it by digging ditches on both sides of the stables, moving them into the ditches, and then diverting the rivers Alpheios and Peneios to wash the ditches clean.

- 6. Slay the Stymphalian Birds

- these aggressive man-eating birds were terrorizing a forest near Lake Stymphalia in northern Arcadia. Heracles scared them with a rattle given to him by Athena, to frighten them into flight away from the forest, allowing him to shoot many of them with his bow and arrow and bring back this proof of his success to Eurystheus.

- 7. Capture the Cretan Bull

- the harmful bull, father of the Minotaur, was laying waste to the lands round Knossos on Crete. It embodied the rage of Poseidon at having his gift (the Bull) to Minos diverted from the intention to sacrifice it to himself. Heracles captured it, and carried it on his shoulders to Eurystheus in Tiryns. Eurystheus released it, when it wandered to Marathon which it then terrorized, until killed by Theseus.

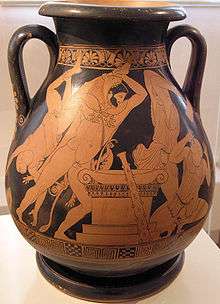

- 8. Steal the Mares of Diomedes

- stealing the horses from Diomedes' stables that had been trained by their owner to feed on human flesh was his next challenge. Heracles' task was to capture them and hand them over to Eurystheus. He accomplished this task by feeding King Diomedes to the animals before binding their mouths shut.

- 9. Obtain the girdle of Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons

- Hippolyta was an Amazon queen and she had a girdle given to her by her father. Heracles had to retrieve the girdle and return it to Eurystheus. He and his band of companions received a rough welcome because, ordered by Hera, the Amazons were supposed to attack them; however, against all odds, Heracles completed the task and secured the girdle for Eurystheus.

- 10. Obtain the cattle of the monster Geryon

- the next challenge was to capture the herd guarded by a two-headed dog called Orthrus, the herdsman Erytion and the owner, Geryon; a giant with three heads and six arms. He killed the first two with his club and the third with a poisoned arrow. Heracles then herded the cattle and, with difficulty, took them to Eurytheus.

- 11. Steal the golden apples of the Hesperides

- these sacred fruits were protected by Hera who had set Ladon, a fearsome hundred-headed dragon as the guardian. Heracles had to first find where the garden was; he asked Nereus for help. He came across Prometheus on his journey. Heracles shot the eagle eating at his liver, and in return he helped Heracles with knowledge that his brother would know where the garden was. His brother Atlas offered him help with the apples if he would hold up the heavens while he was gone. Atlas tricked him and did not return. Heracles returned the trickery and managed to get Atlas taking the burden of the heavens once again, and returned the apples to Mycenae.

- 12. Capture and bring back Cerberus

- his last labour and undoubtedly the riskiest. Eurystheus was so frustrated that Heracles was completing all the tasks that he had given him that he imposed one he believed to be impossible: Heracles had to go down into the underworld of Hades and capture the ferocious three-headed dog Cerberus who guarded the gates. He used the souls to help convince Hades to hand over the dog. He agreed to give him the dog if he used no weapons to obtain him. Heracles succeeded and took the creature back to Mycenae, causing Eurystheus to be fearful of the power and strength of this hero.

Further adventures

After completing these tasks, Heracles fell in love with Princess Iole of Oechalia. King Eurytus of Oechalia promised his daughter, Iole, to whoever could beat his sons in an archery contest. Heracles won but Eurytus abandoned his promise. Heracles' advances were spurned by the king and his sons, except for one: Iole's brother Iphitus. Heracles killed the king and his sons—excluding Iphitus—and abducted Iole. Iphitus became Heracles' best friend. However, once again, Hera drove Heracles mad and he threw Iphitus over the city wall to his death. Once again, Heracles purified himself through three years of servitude—this time to Queen Omphale of Lydia.

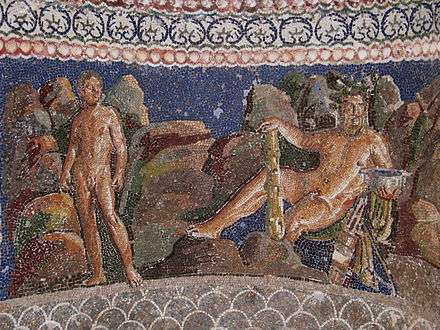

Omphale

Omphale was a queen or princess of Lydia. As penalty for a murder, imposed by Xenoclea, the Delphic Oracle, Heracles was to serve as her slave for a year. He was forced to do women's work and to wear women's clothes, while she wore the skin of the Nemean Lion and carried his olive-wood club. After some time, Omphale freed Heracles and married him. Some sources mention a son born to them who is variously named. It was at that time that the cercopes, mischievous wood spirits, stole Heracles' weapons. He punished them by tying them to a stick with their faces pointing downward.

Hylas

While walking through the wilderness, Heracles was set upon by the Dryopes. In Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica it is recalled that Heracles had mercilessly slain their king, Theiodamas, over one of the latter's bulls, and made war upon the Dryopes "because they gave no heed to justice in their lives".[27] After the death of their king, the Dryopes gave in and offered him Prince Hylas. He took the youth on as his weapons bearer and beloved. Years later, Heracles and Hylas joined the crew of the Argo. As Argonauts, they only participated in part of the journey. In Mysia, Hylas was kidnapped by the nymphs of a local spring. Heracles, heartbroken, searched for a long time but Hylas had fallen in love with the nymphs and never showed up again. In other versions, he simply drowned. Either way, the Argo set sail without them.

Rescue of Prometheus

Hesiod's Theogony and Aeschylus' Prometheus Unbound both tell that Heracles shot and killed the eagle that tortured Prometheus (which was his punishment by Zeus for stealing fire from the gods and giving it to mortals). Heracles freed the Titan from his chains and his torments. Prometheus then made predictions regarding further deeds of Heracles.

Heracles' constellation

On his way back to Mycenae from Iberia, having obtained the Cattle of Geryon as his tenth labour, Heracles came to Liguria in North-Western Italy where he engaged in battle with two giants, Albion and Bergion or Dercynus, sons of Poseidon. The opponents were strong; Hercules was in a difficult position so he prayed to his father Zeus for help. Under the aegis of Zeus, Heracles won the battle. It was this kneeling position of Heracles when he prayed to his father Zeus that gave the name Engonasin ("Εγγόνασιν", derived from "εν γόνασιν"), meaning "on his knees" or "the Kneeler", to the constellation known as Heracles' constellation. The story, among others, is described by Dionysius of Halicarnassus.[28]

Heracles' sack of Troy

Before Homer's Trojan War, Heracles had made an expedition to Troy and sacked it. Previously, Poseidon had sent a sea monster (Greek: kētŏs, Latin: cetus) to attack Troy. The story is related in several digressions in the Iliad (7.451–53; 20.145–48; 21.442–57) and is found in pseudo-Apollodorus' Bibliotheke (2.5.9). This expedition became the theme of the Eastern pediment of the Temple of Aphaea. Laomedon planned on sacrificing his daughter Hesione to Poseidon in the hope of appeasing him. Heracles happened to arrive (along with Telamon and Oicles) and agreed to kill the monster if Laomedon would give him the horses received from Zeus as compensation for Zeus' kidnapping Ganymede. Laomedon agreed. Heracles killed the monster, but Laomedon went back on his word. Accordingly, in a later expedition, Heracles and his followers attacked Troy and sacked it. Then they slew all Laomedon's sons present there save Podarces, who was renamed Priam, who saved his own life by giving Heracles a golden veil Hesione had made. Telamon took Hesione as a war prize and they had a son, Teucer.

Colony at Sardinia

After Heracles had performed his Labours, gods told him that before he passed into the company of the gods, he should create a colony at Sardinia and make his sons, whom he had with the daughters of Thespius, the leaders of the settlement. When his sons became adults, he sent them together with Iolaus to the island.[29][30]

Other adventures

- Heracles defeated the Bebryces (ruled by King Mygdon) and gave their land to Prince Lycus of Mysia, son of Dascylus.

- He killed the robber Termerus.

- Heracles visited Evander with Antor, who then stayed in Italy.

- Heracles killed King Amyntor of Ormenium for not allowing him into his kingdom. He also killed King Emathion of Arabia.

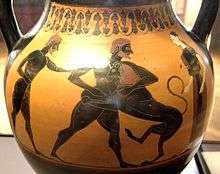

- Heracles kills the Egyptian King Busiris and his followers after they attempt to sacrifice him to the gods.

- Heracles killed Lityerses after beating him in a contest of harvesting.

- Heracles killed Periclymenus at Pylos.

- Heracles killed Syleus for forcing strangers to hoe a vineyard.

- Heracles rivaled with Lepreus and eventually killed him.

- Heracles founded the city Tarentum (modern Taranto in Italy).

- Heracles learned music from Linus (and Eumolpus), but killed him after Linus corrected his mistakes. He learned how to wrestle from Autolycus. He killed the famous boxer Eryx of Sicily in a match.

- Heracles was an Argonaut. He killed Alastor and his brothers.

- When Hippocoon overthrew his brother, Tyndareus, as King of Sparta, Heracles reinstated the rightful ruler and killed Hippocoon and his sons.

- Heracles killed Cycnus, the son of Ares. The expedition against Cycnus, in which Iolaus accompanied Heracles, is the ostensible theme of a short epic attributed to Hesiod, Shield of Heracles.

- Heracles killed the Giants Alcyoneus and Porphyrion.

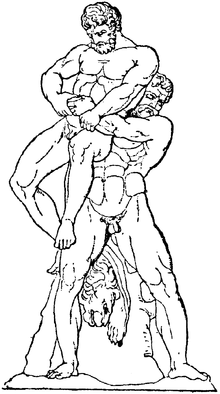

- Heracles killed Antaeus the giant who was immortal while touching the earth, by picking him up and holding him in the air while strangling him.

- Pygmies tried to kill Heracles because they were brothers of Antaeus and wanted to avenge Antaeus's death.[31][32]

- Heracles went to war with Augeias after he denied him a promised reward for clearing his stables. Augeias remained undefeated due to the skill of his two generals, the Molionides, and after Heracles fell ill, his army was badly beaten. Later, however, he was able to ambush and kill the Molionides, and thus march into Elis, sack it, and kill Augeias and his sons.

- Heracles visited the house of Admetus on the day Admetus' wife, Alcestis, had agreed to die in his place. Admetus, not wanting to turn Heracles away, nor wanting to burden him with his sadness, welcomes him and instructs the servants not to inform Heracles of what has occurred. Heracles, thus unaware of Alcestis's fate, enjoys the hospitality of Admetus's house, drinking and revelling, which angers the servants, who wish to mourn as is their right. One scolds the guest and Heracles is ashamed of his actions. By hiding beside the grave of Alcestis, Heracles was able to surprise Death when he came to collect her, and by squeezing him tight until he relented, was able to persuade Death to return Alcestis to her husband.

- Heracles challenged wine god Dionysus to a drinking contest and lost, resulting in his joining the Thiasus for a period.

- Heracles also appears in Aristophanes' The Frogs, in which Dionysus seeks out the hero to find a way to the underworld. Heracles is greatly amused by Dionysus' appearance and jokingly offers several ways to commit suicide before finally offering his knowledge of how to get to there.

- Heracles appears as the ancestral hero of Scythia in Herodotus' text. While Heracles is sleeping out in the wilderness, a half-woman, half-snake creature steals his horses. Heracles eventually finds the creature, but she refuses to return the horses until he has sex with her. After doing so, he takes back his horses, but before leaving, he hands over his belt and bow, and gives instructions as to which of their children should found a new nation in Scythia.

- In the fifth book of the New History, ascribed by Photius to Ptolemy Hephaestion, mention that Heracles did not wear the skin of the Nemean lion, but that of a certain Lion giant killed by Heracles whom he had challenged to single combat.[33]

- Herakles fought and killed Cacus.[34][35]

- Herakles fought with the Sicani people, killing many including the famous Leucaspis.[36]

Death

This is described in Sophocles's Trachiniae and in Ovid's Metamorphoses Book IX. Having wrestled and defeated Achelous, god of the Acheloos river, Heracles takes Deianira as his wife. Travelling to Tiryns, a centaur, Nessus, offers to help Deianira across a fast flowing river while Heracles swims it. However, Nessus is true to the archetype of the mischievous centaur and tries to steal Deianira away while Heracles is still in the water. Angry, Heracles shoots him with his arrows dipped in the poisonous blood of the Lernaean Hydra. Thinking of revenge, Nessus gives Deianira his blood-soaked tunic before he dies, telling her it will "excite the love of her husband".[37]

Several years later, rumor tells Deianira that she has a rival for the love of Heracles. Deianira, remembering Nessus' words, gives Heracles the bloodstained shirt. Lichas, the herald, delivers the shirt to Heracles. However, it is still covered in the Hydra's blood from Heracles' arrows, and this poisons him, tearing his skin and exposing his bones. Before he dies, Heracles throws Lichas into the sea, thinking he was the one who poisoned him (according to several versions, Lichas turns to stone, becoming a rock standing in the sea, named for him). Heracles then uproots several trees and builds a funeral pyre on Mount Oeta, which Poeas, father of Philoctetes, lights. As his body burns, only his immortal side is left. Through Zeus' apotheosis, Heracles rises to Olympus as he dies.

No one but Heracles' friend Philoctetes (Poeas in some versions) would light his funeral pyre (in an alternative version, it is Iolaus who lights the pyre). For this action, Philoctetes or Poeas received Heracles' bow and arrows, which were later needed by the Greeks to defeat Troy in the Trojan War.

Philoctetes confronted Paris and shot a poisoned arrow at him. The Hydra poison subsequently led to the death of Paris. The Trojan War, however, continued until the Trojan Horse was used to defeat Troy.

According to Herodotus, Heracles lived 900 years before Herodotus' own time (c. 1300 BCE).[38]

Lovers

Women

Marriages

During the course of his life, Heracles married four times.

- His first marriage was to Megara, whose children he murdered in a fit of madness. According to Pseudo-Apollodorus (Bibliotheca, 2.4.12) Megara was unharmed. According to Hyginus (Fabulae, 32), Heracles also killed Megara.

- His second wife was Omphale, the Lydian queen to whom he was delivered as a slave (Hyginus, Fabulae, 32).

- His third marriage was to Deianira, for whom he had to fight the river god Achelous (upon Achelous' death, Heracles removed one of his horns and gave it to some nymphs who turned it into the cornucopia). Soon after they wed, Heracles and Deianira had to cross a river, and a centaur named Nessus offered to help Deianira across but then attempted to rape her. Enraged, Heracles shot the centaur from the opposite shore with a poisoned arrow (tipped with the Lernaean Hydra's blood) and killed him. As he lay dying, Nessus plotted revenge, told Deianira to gather up his blood and spilled semen and, if she ever wanted to prevent Heracles from having affairs with other women, she should apply them to his vestments. Nessus knew that his blood had become tainted by the poisonous blood of the Hydra, and would burn through the skin of anyone it touched. Later, when Deianira suspected that Heracles was fond of Iole, she soaked a shirt of his in the mixture, creating the poisoned shirt of Nessus. Heracles' servant, Lichas, brought him the shirt and he put it on. Instantly he was in agony, the cloth burning into him. As he tried to remove it, the flesh ripped from his bones. Heracles chose a voluntary death, asking that a pyre be built for him to end his suffering. After death, the gods transformed him into an immortal, or alternatively, the fire burned away the mortal part of the demigod, so that only the god remained. After his mortal parts had been incinerated, he could become a full god and join his father and the other Olympians on Mount Olympus.

- His fourth marriage was to Hebe, his last wife.

Affairs

An episode of his female affairs that stands out was his stay at the palace of Thespius, king of Thespiae, who wished him to kill the Lion of Cithaeron. As a reward, the king offered him the chance to perform sexual intercourse with all fifty of his daughters in one night. Heracles complied and they all became pregnant and all bore sons. This is sometimes referred to as his Thirteenth Labour. Many of the kings of ancient Greece traced their lines to one or another of these, notably the kings of Sparta and Macedon.

Yet another episode of his female affairs that stands out was when he carried away the oxen of Geryon, he also visited the country of the Scythians. Once there, while asleep, his horses suddenly disappeared. When he woke and wandered about in search of them, he came into the country of Hylaea. He then found the dracaena of Scythia (sometimes identified as Echidna) in a cave. When he asked whether she knew anything about his horses, she answered, that they were in her own possession, but that she would not give them up, unless he would consent to stay with her for a time. Heracles accepted the request, and became by her the father of Agathyrsus, Gelonus, and Scythes. The last of them became king of the Scythians, according to his father's arrangement, because he was the only one among the three brothers that was able to manage the bow which Heracles had left behind and to use his father's girdle.[39]

Dionysius of Halicarnassus writes that Heracles and Lavinia, daughter of Evander, had a son named Pallas.[40]

Men

As a symbol of masculinity and warriorship, Heracles also had a number of male lovers. Plutarch, in his Eroticos, maintains that Heracles' male lovers were beyond counting. Of these, the one most closely linked to Heracles is the Theban Iolaus. According to a myth thought to be of ancient origins, Iolaus was Heracles' charioteer and squire. Heracles in the end helped Iolaus find a wife. Plutarch reports that down to his own time, male couples would go to Iolaus's tomb in Thebes to swear an oath of loyalty to the hero and to each other.[41][42] He also mentions Admetus, known in myth for assisting in the hunt for the Calydonian Boar, as one of Heracles's male lovers.[43]

One of Heracles' male lovers, and one represented in ancient as well as modern art, is Hylas.[44]

Another reputed male lover of Heracles is Elacatas, who was honored in Sparta with a sanctuary and yearly games, Elacatea. The myth of their love is an ancient one.[45]

Abdera's eponymous hero, Abderus, was another of Heracles' lovers. He was said to have been entrusted with—and slain by—the carnivorous mares of Thracian Diomedes. Heracles founded the city of Abdera in Thrace in his memory, where he was honored with athletic games.[46]

Another myth is that of Iphitus.[47]

Another story is the one of his love for Nireus, who was "the most beautiful man who came beneath Ilion" (Iliad, 673). But Ptolemy adds that certain authors made Nireus out to be a son of Heracles.[48]

Pausanias makes mention of Sostratus, a youth of Dyme, Achaea, as a lover of Heracles. Sostratus was said to have died young and to have been buried by Heracles outside the city. The tomb was still there in historical times, and the inhabitants of Dyme honored Sostratus as a hero.[49] The youth seems to have also been referred to as Polystratus.

A series of lovers are only known in later literature. Among these are Eurystheus,[50] Adonis,[51] Corythus,[51] and Nestor who was said to have been loved for his wisdom. In the account of Ptolemaeus Chennus, Nestor's role as lover explains why he was the only son of Neleus to be spared by the hero.[52]

A scholiast commenting on Apollonius' Argonautica lists the following male lovers of Heracles: "Hylas, Philoctetes, Diomus, Perithoas, and Phrix, after whom a city in Libya was named".[53] Diomus is also mentioned by Stephanus of Byzantium as the eponym of the deme Diomeia of the Attic phyle Aegeis: Heracles is said to have fallen in love with Diomus when he was received as guest by Diomus' father Collytus.[54] Perithoas and Phrix are otherwise unknown, and so is the version that suggests a sexual relationship between Heracles and Philoctetes.

Children

All of Heracles' marriages and almost all of his heterosexual affairs resulted in births of a number of sons and at least four daughters. One of the most prominent is Hyllus, the son of Heracles and Deianeira or Melite. The term Heracleidae, although it could refer to all of Heracles' children and further descendants, is most commonly used to indicate the descendants of Hyllus, in the context of their lasting struggle for return to Peloponnesus, out of where Hyllus and his brothers—the children of Heracles by Deianeira—were thought to have been expelled by Eurystheus.

The children of Heracles by Megara are collectively well known because of their ill fate, but there is some disagreement among sources as to their number and individual names. Apollodorus lists three, Therimachus, Creontiades and Deicoon;[55] to these Hyginus[56] adds Ophitus and, probably by mistake, Archelaus, who is otherwise known to have belonged to the Heracleidae, but to have lived several generations later. A scholiast on Pindar' s odes provides a list of seven completely different names: Anicetus, Chersibius, Mecistophonus, Menebrontes, Patrocles, Polydorus, Toxocleitus.[57]

Other well-known children of Heracles include Telephus, king of Mysia (by Auge), and Tlepolemus, one of the Greek commanders in the Trojan War (by Astyoche).

According to Herodotus, a line of 22 Kings of Lydia descended from Hercules and Omphale. The line was called Tylonids after his Lydian name.

The divine sons of Heracles and Hebe are Alexiares and Anicetus.

Consorts and children

- Megara

- Therimachus

- Creontiades

- Ophitus

- Deicoon

- Omphale

- Agelaus

- Tyrsenus

- Deianira

- Hebe

- Astydameia, daughter of Ormenus or Amyntor

- Astyoche, daughter of Phylas

- Auge

- Autonoë, daughter of Piraeus / Iphinoe, daughter of Antaeus

- Palaemon

- Baletia, daughter of Baletus

- Brettus[58]

- Barge

- Bargasus[59]

- Bolbe

- Celtine

- Chalciope

- Chania, nymph

- Gelon[60]

- The Scythian dracaena or Echidna

- Epicaste

- Thestalus

- Lavinia, daughter of Evander[61]

- Pallas

- Malis, a slave of Omphale

- Acelus[62]

- Meda

- Melite (heroine)

- Melite (naiad)

- Hyllus (possibly)

- Myrto

- Palantho of Hyperborea[63]

- Latinus[61]

- Parthenope, daughter of Stymphalus (son of Elatus)

- Everes

- Phialo

- Aechmagoras

- Psophis

- Pyrene

- none known

- Rhea, Italian priestess

- Thebe (daughter of Adramys)

- Tinge, wife of Antaeus

- 50 daughters of Thespius

- 50 sons, see Thespius#Daughters and grandchildren

- Unnamed Celtic woman

- Galates[66]

- Unnamed female slave of Iardanus

- Unnamed daughter of Syleus (Xenodoce?)[67]

- Unknown consorts

Heracles around the world

Rome

In Rome, Heracles was honored as Hercules, and had a number of distinctively Roman myths and practices associated with him under that name.

Egypt

Herodotus connected Heracles to the Egyptian god Shu. Also he was associated with Khonsu, another Egyptian god who was in some ways similar to Shu. As Khonsu, Heracles was worshipped at the now sunken city of Heracleion, where a large temple was constructed.

Most often the Egyptians identified Heracles with Heryshaf, transcribed in Greek as Arsaphes or Harsaphes (Ἁρσαφής). He was an ancient ram-god whose cult was centered in Herakleopolis Magna.

Other cultures

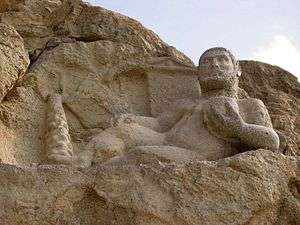

Hellenistic-era depiction of the Zoroastrian divinity Bahram as Hercules carved in 153 BCE at Kermanshah, Iran.

Hellenistic-era depiction of the Zoroastrian divinity Bahram as Hercules carved in 153 BCE at Kermanshah, Iran.

Via the Greco-Buddhist culture, Heraclean symbolism was transmitted to the Far East. An example remains to this day in the Nio guardian deities in front of Japanese Buddhist temples.

Herodotus also connected Heracles to Phoenician god Melqart.

Sallust mentions in his work on the Jugurthine War that the Africans believe Heracles to have died in Spain where, his multicultural army being left without a leader, the Medes, Persians, and Armenians who were once under his command split off and populated the Mediterranean coast of Africa.[77]

Temples dedicated to Heracles abounded all along the Mediterranean coastal countries. For example, the temple of Heracles Monoikos (i.e. the lone dweller), built far from any nearby town upon a promontory in what is now the Côte d'Azur, gave its name to the area's more recent name, Monaco.

The gateway to the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean, where the southernmost tip of Spain and the northernmost of Morocco face each other is, classically speaking, referred to as the Pillars of Hercules/Heracles, owing to the story that he set up two massive spires of stone to stabilise the area and ensure the safety of ships sailing between the two landmasses.

Uses of Heracles as a name

In various languages, variants of Hercules' name are used as a male given name, such as Hercule in French, Hércules in Spanish, Iraklis (Greek: Ηρακλής) in Modern Greek and Irakli (Georgian: ირაკლი, translit.: irak'li) in Georgian.

There are many teams around the world that have this name or have Heracles as their symbol. The most popular in Greece is G.S. Iraklis Thessaloniki.

Heracleum is a genus of flowering plants in the carrot family Apiaceae. Some of the species in this genus are quite large. In particular, the giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) is exceptionally large, growing up to 5 m tall.

Ancestry

- Source:[78]

| Zeus | Danaë | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perseus | Andromeda | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perses | Alcaeus | Hipponome | Electryon | Anaxo | Sthenelus | Menippe | Mestor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anaxo | Amphitryon | Alcmene | Zeus | Licymnius | Eurystheus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iphicles | Megara | Heracles | Deianira | Hebe | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Iolaus | Three Children | Hyllus | Macaria | Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Other figures in Greek mythology punished by the gods include

- Figures resembling Heracles in other mythological traditions

Notes

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Alceides". In William Smith (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 98. Archived from the original on 2008-05-27.

- Bibliotheca ii. 4. § 12

- By his adoptive descent through Amphitryon, Heracles receives the epithet Alcides, as "of the line of Alcaeus", father of Amphitryon. Amphitryon's own, mortal son was Iphicles.

- Burkert 1985, pp. 208–09

- Burkert 1985, pp. 208–12.

- Loewen, Nancy: Hercules, p. 15

- Kenyon, Douglas J. (January–February 2018). "[no title cited]". Atlantis Rising Magazine. Vol. 127.

- Robert Fagles' translation, 1996:269.

- Solmsen, Friedrich (1981). "The Sacrifice of Agamemnon's Daughter in Hesiod's' Ehoeae". The American Journal of Philology. 102 (4): 353–58 [355]. JSTOR 294322.

- Ptol. iv. 3. § 37

- Ventura, F. (1988). "Ptolemy's Maltese Co-ordinates". Hyphen. V (6): 253–69.

- Winiarczyk, Marek (2013). The "Sacred History" of Euhemerus of Messene. Walter de Gruyter. p. 30. ISBN 978-3110278880.

- Burkert, Walter (1987). Ancient Mystery Cults. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0674033870.

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (2014). The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0198706779.

- Carney, Elizabeth (2015). King and Court in Ancient Macedonia: Rivalry, Treason and Conspiracy. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales. p. 66. ISBN 978-1910589083.

- Pausanias, Guide to Greece, 4.32.1

- Aelian, Varia Historia, 12.15

- Aelian, Varia Historia, 5.3

- Thorburn, John (2005). The Facts on File Companion to Classical Drama. New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 555. ISBN 978-0816052028.

- Papadopoulou, Thalia (2005). Heracles and Euripidean Tragedy. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780521851268.

- Littlewood, Cedric (2004). Self-representation and Illusion in Senecan Tragedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0199267613.

- Compare the two pairs of twins born to Leda and the "double" parentage of Theseus.

- Diodorus Siculus' Bibliotheca Historica (Book IV, Ch. 9)

- Andrew Ford, Aristotle as Poet, Oxford, 2011, p. 208 n. 5, citing, in addition to Prodicus/Xenophon, Antisthenes, Herodorus (esp. FGrHist 31 F 14), and (in the 4th century) Plato's use of "Heracles as a figure for Socrates' life (and death?): Apology 22a, cf. Theaetetus 175a, Lysis 205c."

- Pausanias Χ 3.1, 36.5. Ptolemaeus, Geogr. Hyph. ΙΙ 184. 12. Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. "Ἀντίκυρα"

- Smith, W., ed. (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography And Mythology. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 393–394. ark:/13960/t9f47mp93.

- Richard Hunter, translator, Jason and the Golden Fleece (Oxford:Clarendon Press), 1993, pp. 31f.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, i. 41

- "Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, Books I–V, book 4, chapter 29". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- "Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, Books I–V, book 4, chapter 29, section 3". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- Philostratus, Imagines, translated by Arthur Fairbanks (1864-1944) edition of 1931

- Philostratus, Imagines, Greek

- Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Book 5 "Heracles did not wear the skin of the Nemean lion, but that of a certain Lion, one of the giants killed by Heracles whom he had challenged to single combat."

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, 1.39.2

- Plutarch, Of Love, Moralia, 18

- Diodorus Siculus, Library, 4.23.5

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, IX l.132–33

- Herodotus, Histories II.145

- Herodotus, Histories IV. 8–10.

- "Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Antiquitates Romanae, Books I–XX, book 1, chapter 32, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- Plutarch, Erotikos, 761d.The tomb of Iolaus is also mentioned by Pindar.

- Pindar, Olympian Odes, 9.98–99.

- Plutarch, Erotikos, 761e.

- Theocritus, Idyll 13; Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 1.1177–1357.

- Sosibius, in Hesychius of Alexandria's Lexicon

- Bibliotheca 2.5.8; Ptolemaeus Chennus, 147b, in Photius' Bibliotheca

- Ptolemaeus Chennus, in Photius' Bibliotheca

- Ptolemaeus Chennus, 147b.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 7. 17. 8

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae, 603d.

- Ptolemaeus Chennus, New History, as summarized in Bibliotheca (Photius)

- Ptolemaeus Chennus, 147e; Philostratus, Heroicus 696, per Sergent, 1986, p. 163.

- Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, 1. 1207

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Diomeia

- Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, 2. 4. 11 = 2. 7. 8

- Fabulae 162

- Scholia on Pindar, Isthmian Ode 3 (4), 104

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Brettos

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Bargasa

- Servius on Virgil's Georgics 2. 115

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, 1. 43. 1

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Akelēs

- Solinus, De mirabilia mundi, 1. 15

- Virgil, Aeneid, 7. 655 ff

- Plutarch, Life of Sertorius, 9. 4

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, 5. 24. 2

- So Conon, Narrationes, 17. In Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2. 6. 3 a daughter of Syleus, Xenodoce, is killed by Heracles

- Statius, Thebaid, 6. 837, 10. 249

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Amathous

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Gaza

- Statius, Thebaid, 6. 346

- Servius on Virgil's Eclogue 9. 30

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, 1. 50. 4

- Hyginus, Fabulae, 162

- In Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Phaistos, Rhopalus is the son of Heracles and Phaestus his own son; in Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2. 6. 7, vice versa (Phaestus son, Rhopalus grandson)

- The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, James C. Harle, Yale University Press, 1994 p. 67

- Sallust (1963). The Jugurthine War/The Conspiracy of Catiline. Translated by S.A. Handford. Penguin Books. p. 54.

- Morford, M. P. O.; Lenardon R. J. (2007). Classical Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 865.

References

- Heracles at Theoi.com Classical literature and art

- Timeless Myths – Heracles The life and adventure of Heracles, including his twelve labours.

- Heracles, Greek Mythology Link

- Heracles (in French)

- Vollmer: Herkules (1836, in German)

- Burkert, Walter, (1977) 1985. Greek Religion (Harvard University Press).

- Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. New York/London: Thames and Hudson.

Further reading

- Brockliss, William. 2017. "The Hesiodic Shield of Heracles: The Text as Nightmarish Vision." Illinois Classical Studies 42.1: 1–19. doi:10.5406/illiclasstud.42.1.0001. JSTOR 10.5406/illiclasstud.42.1.0001.

- Burkert, Walter. 1982. "Heracles and the Master of Animals." In Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual, 78–98. Sather Classical Lectures 47. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Haubold, Johannes. 2005. "Heracles in the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women." In The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women: Constructions and Reconstructions. Edited by Richard Hunter, 85–98. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Karanika, Andromache. 2011. "The End of the Nekyia: Odysseus, Heracles, and the Gorgon in the Underworld." Arethusa 44.1: 1–27.

- Padilla, Mark W. 1998. "Herakles and Animals in the Origins of Comedy and Satyr Drama". In Le Bestiaire d'Héraclès: IIIe Rencontre héracléenne, edited by Corinne Bonnet, Colette Jourdain-Annequin, and Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge, 217–30. Kernos Suppl. 7. Liège: Centre International d'Etude de la Religion Grecque Antique.

- Padilla, Mark W. 1998. "The Myths of Herakles in Ancient Greece: Survey and Profile". Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.

- Papadimitropoulos, Loukas. 2008. "Heracles as Tragic Hero." Classical World 101.2: 131–38. doi:10.1353/clw.2008.0015

- Papadopoulou, Thalia. 2005. Heracles and Euripidean Tragedy. Cambridge Classical Studies. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Segal, Charles Paul. 1961. "The Character and Cults of Dionysus and the Unity of the Frogs." Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 65:207–42. doi:10.2307/310837. JSTOR 310837.

- Stafford, Emma. 2012. Herakles. Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World. New York: Routledge.

- Strid, Ove. 2013. "The Homeric Prefiguration of Sophocles' Heracles." Hermes 141.4: 381–400. JSTOR 43652880.

- Woodford, Susan. 1971. "Cults of Herakles in Attica." In Studies Presented to George M. A. Hanfmann. Edited by David Gordon Mitten, John Griffiths Pedley, and Jane Ayer Scott, 211–25. Monographs in Art and Archaeology 2. Mainz, Germany: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

- Euripides. The Children of Herakles. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Euripides. Heracles. England: Shirley A. Barlow, 1996. Greek Version: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Primary sources

- Homer, Odyssey, 12.072 (7th century BCE)

- Sophocles, Women of Trachis (c. 450 BCE)

- Euripides, Herakles (416 BCE)

- Theocritus, Idylls, 13 (350–310 BCE)

- Callimachus, Aetia (Causes), 24. Thiodamas the Dryopian, Fragments, 160. Hymn to Artemis (310–250? BCE)

- Apollonios Rhodios, Argonautika, I. 1175–1280 (c. 250 BCE)

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.9.19, 2.7.7 (140 BCE)

- Sextus Propertius, Elegies, i.20.17ff (50–15 BCE)

- Ovid, Metamorphoses (8 CE)

- Ovid, Ibis, 488 (8–18 CE)

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica, I.110, III.535, 560, IV.1–57 (1st century)

- Hyginus, Fables, 14. Argonauts Assembled (1st century)

- Philostratus the Elder, Images, ii.24 Thiodamas (170–245)

- First Vatican Mythographer, 49. Hercules et Hylas

External links

| Library resources about Heracles |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heracles. |

- Heracles at the Encyclopædia Britannica