Athena

Athena[lower-alpha 2] or Athene,[lower-alpha 3] often given the epithet Pallas,[lower-alpha 4] is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, handicraft, and warfare[3] who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva.[4] Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of various cities across Greece, particularly the city of Athens, from which she most likely received her name.[5] She's usually shown in art wearing a helmet and holding a spear. Her major symbols include owls, olive trees, snakes, and the Gorgoneion.

| Athena Ἀθηνᾶ | |

|---|---|

Goddess of wisdom, olives, weaving, and battle strategy | |

Mattei Athena at Louvre. Roman copy from the 1st century BC/AD after a Greek original of the 4th century BC, attributed to Cephisodotos or Euphranor. | |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Symbol | Owls, olive trees, snakes, Aegis, armour, helmets, spears, Gorgoneion |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | In the Iliad: Zeus alone In Theogony: Zeus and Metis[lower-alpha 1] |

| Siblings | Aeacus, Angelos, Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Children | No natural children, but Erichthonius of Athens was her adoptive son |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman equivalent | Minerva |

| Etruscan equivalent | Menrva |

| Canaanite equivalent | Anat[2] |

| Egyptian equivalent | Neith |

| Celtic equivalent | Sulis |

From her origin as an Aegean palace goddess, Athena was closely associated with the city. She was known as Polias and Poliouchos (both derived from polis, meaning "city-state"), and her temples were usually located atop the fortified acropolis in the central part of the city. The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis is dedicated to her, along with numerous other temples and monuments. As the patron of craft and weaving, Athena was known as Ergane. She's also a warrior goddess, and was believed to lead soldiers into battle as Athena Promachos. Her main festival in Athens was the Panathenaia, which was celebrated during the month of Hekatombaion in midsummer and was the most important festival on the Athenian calendar.

In Greek mythology, Athena was believed to have been born from the head of her father Zeus. In the founding myth of Athens, Athena bested Poseidon in a competition over patronage of the city by creating the first olive tree. She's known as Athena Parthenos "Athena the Virgin," but in one archaic Attic myth, the god Hephaestus tried and failed to rape her, resulting in Gaia giving birth to Erichthonius, an important Athenian founding hero. Athena was the patron goddess of heroic endeavor; she was believed to have aided the heroes Perseus, Heracles, Bellerophon, and Jason. Along with Aphrodite and Hera, Athena was one of the three goddesses whose feud resulted in the beginning of the Trojan War.

She plays an active role in the Iliad, in which she assists the Achaeans and, in the Odyssey, she is the divine counselor to Odysseus. In the later writings of the Roman poet Ovid, Athena was said to have competed against the mortal Arachne in a weaving competition, afterwards transforming Arachne into the first spider; Ovid also describes how she transformed Medusa into a Gorgon after witnessing her being raped by Poseidon in her temple. Since the Renaissance, Athena has become an international symbol of wisdom, the arts, and classical learning. Western artists and allegorists have often used Athena as a symbol of freedom and democracy.

Etymology

Athena is associated with the city of Athens.[5][7] The name of the city in ancient Greek is Ἀθῆναι (Athȇnai), a plural toponym, designating the place where—according to myth—she presided over the Athenai, a sisterhood devoted to her worship.[6] In ancient times, scholars argued whether Athena was named after Athens or Athens after Athena.[5] Now scholars generally agree that the goddess takes her name from the city;[5][7] the ending -ene is common in names of locations, but rare for personal names.[5] Testimonies from different cities in ancient Greece attest that similar city goddesses were worshipped in other cities[6] and, like Athena, took their names from the cities where they were worshipped.[6] For example, in Mycenae there was a goddess called Mykene, whose sisterhood was known as Mykenai,[6] whereas at Thebes an analogous deity was called Thebe, and the city was known under the plural form Thebai (or Thebes, in English, where the 's' is the plural formation).[6] The name Athenai is likely of Pre-Greek origin because it contains the presumably Pre-Greek morpheme *-ān-.[8]

In his dialogue Cratylus, the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428–347 BC) gives some rather imaginative etymologies of Athena's name, based on the theories of the ancient Athenians and his own etymological speculations:

That is a graver matter, and there, my friend, the modern interpreters of Homer may, I think, assist in explaining the view of the ancients. For most of these in their explanations of the poet, assert that he meant by Athena "mind" [νοῦς, noũs] and "intelligence" [διάνοια, diánoia], and the maker of names appears to have had a singular notion about her; and indeed calls her by a still higher title, "divine intelligence" [θεοῦ νόησις, theoũ nóēsis], as though he would say: This is she who has the mind of God [ἁ θεονόα, a theonóa). Perhaps, however, the name Theonoe may mean "she who knows divine things" [τὰ θεῖα νοοῦσα, ta theia noousa] better than others. Nor shall we be far wrong in supposing that the author of it wished to identify this Goddess with moral intelligence [εν έθει νόεσιν, en éthei nóesin], and therefore gave her the name Etheonoe; which, however, either he or his successors have altered into what they thought a nicer form, and called her Athena.

— Plato, Cratylus 407b

Thus, Plato believed that Athena's name was derived from Greek Ἀθεονόα, Atheonóa—which the later Greeks rationalised as from the deity's (θεός, theós) mind (νοῦς, noũs). The second-century AD orator Aelius Aristides attempted to derive natural symbols from the etymological roots of Athena's names to be aether, air, earth, and moon.[9]

Origins

Athena was originally the Aegean goddess of the palace, who presided over household crafts and protected the king.[11][12][13][14] A single Mycenaean Greek inscription 𐀀𐀲𐀙𐀡𐀴𐀛𐀊 a-ta-na po-ti-ni-ja /Athana potnia/ appears at Knossos in the Linear B tablets from the Late Minoan II-era "Room of the Chariot Tablets";[15][16][10] these comprise the earliest Linear B archive anywhere.[16] Although Athana potnia is often translated Mistress Athena,[17] it could also mean "the Potnia of Athana", or the Lady of Athens.[17][10] However, any connection to the city of Athens in the Knossos inscription is uncertain.[18] A sign series a-ta-no-dju-wa-ja appears in the still undeciphered corpus of Linear A tablets, written in the unclassified Minoan language.[19] This could be connected with the Linear B Mycenaean expressions a-ta-na po-ti-ni-ja and di-u-ja or di-wi-ja (Diwia, "of Zeus" or, possibly, related to a homonymous goddess),[16] resulting in a translation "Athena of Zeus" or "divine Athena". Similarly, in the Greek mythology and epic tradition, Athena figures as a daughter of Zeus (Διός θυγάτηρ; cfr. Dyeus).[20] However, the inscription quoted seems to be very similar to "a-ta-nū-tī wa-ya", quoted as SY Za 1 by Jan Best.[20] Best translates the initial a-ta-nū-tī, which is recurrent in line beginnings, as "I have given".[20]

A Mycenean fresco depicts two women extending their hands towards a central figure, who is covered by an enormous figure-eight shield; this may depict the warrior-goddess with her palladion, or her palladion in an aniconic representation.[21][22] In the "Procession Fresco" at Knossos, which was reconstructed by the Mycenaeans,[23] two rows of figures carrying vessels seem to meet in front of a central figure,[23] which is probably the Minoan precursor to Athena.[23] The early twentieth-century scholar Martin Persson Nilsson argued that the Minoan snake goddess figurines are early representations of Athena.[11][12]

Nilsson and others have claimed that, in early times, Athena was either an owl herself or a bird goddess in general.[24] In the third book of the Odyssey, she takes the form of a sea-eagle.[24] Proponents of this view argue that she dropped her prophylactic owl-mask before she lost her wings. "Athena, by the time she appears in art," Jane Ellen Harrison remarks, "has completely shed her animal form, has reduced the shapes she once wore of snake and bird to attributes, but occasionally in black-figure vase-paintings she still appears with wings."[25]

It is generally agreed that the cult of Athena preserves some aspects of the Proto-Indo-European transfunctional goddess.[27][28] The cult of Athena may have also been influenced by those of Near Eastern warrior goddesses such as the East Semitic Ishtar and the Ugaritic Anat,[12][10] both of whom were often portrayed bearing arms.[12] Classical scholar Charles Penglase notes that Athena closely resembles Inanna in her role as a "terrifying warrior goddess"[29] and that both goddesses were closely linked with creation.[29] Athena's birth from the head of Zeus may be derived from the earlier Sumerian myth of Inanna's descent into and return from the Underworld.[30][31]

Plato notes that the citizens of Sais in Egypt worshipped a goddess known as Neith,[lower-alpha 5] whom he identifies with Athena.[32] Neith was the ancient Egyptian goddess of war and hunting, who was also associated with weaving; her worship began during the Egyptian Pre-Dynastic period. In Greek mythology, Athena was reported to have visited mythological sites in North Africa, including Libya's Triton River and the Phlegraean plain.[lower-alpha 6] Based on these similarities, the Sinologist Martin Bernal created the "Black Athena" hypothesis, which claimed that Neith was brought to Greece from Egypt, along with "an enormous number of features of civilization and culture in the third and second millennia".[33][34] The "Black Athena" hypothesis stirred up widespread controversy near the end of the twentieth century,[35][36] but it has now been widely rejected by modern scholars.[37][38]

Cult and patronages

Panhellenic and Athenian cult

In her aspect of Athena Polias, Athena was venerated as the goddess of the city and the protectress of the citadel.[12][39][40] In Athens, the Plynteria, or "Feast of the Bath", was observed every year at the end of the month of Thargelion.[41] The festival lasted for five days. During this period, the priestesses of Athena, or plyntrídes, performed a cleansing ritual within the Erechtheion, a sanctuary devoted to Athena and Poseidon.[42] Here Athena's statue was undressed, her clothes washed, and body purified.[42] Athena was worshipped at festivals such as Chalceia as Athena Ergane,[43][40] the patroness of various crafts, especially weaving.[43][40] She was also the patron of metalworkers and was believed to aid in the forging of armor and weapons.[43] During the late fifth century BC, the role of goddess of philosophy became a major aspect of Athena's cult.[44]

As Athena Promachos, she was believed to lead soldiers into battle.[45][46] Athena represented the disciplined, strategic side of war, in contrast to her brother Ares, the patron of violence, bloodlust, and slaughter—"the raw force of war".[47][48] Athena was believed to only support those fighting for a just cause[47] and was thought to view war primarily as a means to resolve conflict.[47] The Greeks regarded Athena with much higher esteem than Ares.[47][48] Athena was especially worshipped in this role during the festivals of the Panathenaea and Pamboeotia,[49] both of which prominently featured displays of athletic and military prowess.[49] As the patroness of heroes and warriors, Athena was believed to favor those who used cunning and intelligence rather than brute strength.[50]

In her aspect as a warrior maiden, Athena was known as Parthenos (Παρθένος "virgin"),[45][52][53] because, like her fellow goddesses Artemis and Hestia, she was believed to remain perpetually a virgin.[54][55][45][53][56] Athena's most famous temple, the Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, takes its name from this title.[56] According to Karl Kerényi, a scholar of Greek mythology, the name Parthenos is not merely an observation of Athena's virginity, but also a recognition of her role as enforcer of rules of sexual modesty and ritual mystery.[56] Even beyond recognition, the Athenians allotted the goddess value based on this pureness of virginity, which they upheld as a rudiment of female behavior.[56] Kerényi's study and theory of Athena explains her virginal epithet as a result of her relationship to her father Zeus and a vital, cohesive piece of her character throughout the ages.[56] This role is expressed in a number of stories about Athena. Marinus of Neapolis reports that when Christians removed the statue of the goddess from the Parthenon, a beautiful woman appeared in a dream to Proclus, a devotee of Athena, and announced that the "Athenian Lady" wished to dwell with him.[57]

Regional cults

Athena was not only the patron goddess of Athens, but also other cities, including Argos, Sparta, Gortyn, Lindos, and Larisa.[46] The various cults of Athena were all branches of her panhellenic cult[46] and often proctored various initiation rites of Grecian youth, such as the passage into citizenship by young men or the passage of young women into marriage.[46] These cults were portals of a uniform socialization, even beyond mainland Greece.[46] Athena was frequently equated with Aphaea, a local goddess of the island of Aegina, originally from Crete and also associated with Artemis and the nymph Britomartis.[58] In Arcadia, she was assimilated with the ancient goddess Alea and worshiped as Athena Alea.[59] Sanctuaries dedicated to Athena Alea were located in the Laconian towns of Mantineia and Tegea. The temple of Athena Alea in Tegea was an important religious center of ancient Greece.[lower-alpha 7] The geographer Pausanias was informed that the temenos had been founded by Aleus.[60]

Athena had a major temple on the Spartan Acropolis,[61][40] where she was venerated as Poliouchos and Khalkíoikos ("of the Brazen House", often latinized as Chalcioecus).[61][40] This epithet may refer to the fact that cult statue held there may have been made of bronze,[61] that the walls of the temple itself may have been made of bronze,[61] or that Athena was the patron of metal-workers.[61] Bells made of terracotta and bronze were used in Sparta as part of Athena's cult.[61] An Ionic-style temple to Athena Polias was built at Priene in the fourth century BC.[62] It was designed by Pytheos of Priene,[63] the same architect who designed the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.[63] The temple was dedicated by Alexander the Great[64] and an inscription from the temple declaring his dedication is now held in the British Museum.[62]

Epithets and attributes

Athena was known as Atrytone (Άτρυτώνη "the Unwearying"), Parthenos (Παρθένος "Virgin"), and Promachos (Πρόμαχος "she who fights in front"). The epithet Polias (Πολιάς "of the city"), refers to Athena's role as protectress of the city.[46] The epithet Ergane (Εργάνη "the Industrious") pointed her out as the patron of craftsmen and artisans.[46] Burkert notes that the Athenians sometimes simply called Athena "the Goddess", hē theós (ἡ θεός), certainly an ancient title.[5] After serving as the judge at the trial of Orestes in which he was acquitted of having murdered his mother Clytemnestra, Athena won the epithet Areia (Αρεία).[46]

Athena was sometimes given the epithet Hippia (Ἵππια "of the horses", "equestrian"),[40][65] referring to her invention of the bit, bridle, chariot, and wagon.[40] The Greek geographer Pausanias mentions in his Guide to Greece that the temple of Athena Chalinitis ("the bridler")[65] in Corinth was located near the tomb of Medea's children.[65] Other epithets include Ageleia, Itonia and Aethyia, under which she was worshiped in Megara.[66][67] The word aíthyia (αἴθυια) signifies a "diver", also some diving bird species (possibly the shearwater) and figuratively, a "ship", so the name must reference Athena teaching the art of shipbuilding or navigation.[68] In a temple at Phrixa in Elis, reportedly built by Clymenus, she was known as Cydonia (Κυδωνία).[69]

The Greek biographer Plutarch (AD 46–120) refers to an instance during the Parthenon's construction of her being called Athena Hygieia (Ὑγίεια, i. e. personified "Health") after inspiring a physician to a successful course of treatment.[70]

In Homer's epic works, Athena's most common epithet is Glaukopis (γλαυκῶπις), which usually is translated as, "bright-eyed" or "with gleaming eyes".[71] The word is a combination of glaukós (γλαυκός, meaning "gleaming, silvery", and later, "bluish-green" or "gray")[72] and ṓps (ὤψ, "eye, face").[73] The word glaúx (γλαύξ,[74] "little owl")[75] is from the same root, presumably according to some, because of the bird's own distinctive eyes. Athena was clearly associated with the owl from very early on;[76] in archaic images, she is frequently depicted with an owl perched on her hand.[76] Through its association with Athena, the owl evolved into the national mascot of the Athenians and eventually became a symbol of wisdom.[4]

In the Iliad (4.514), the Odyssey (3.378), the Homeric Hymns, and in Hesiod's Theogony, Athena is also given the curious epithet Tritogeneia (Τριτογένεια), whose significance remains unclear.[77] It could mean various things, including "Triton-born", perhaps indicating that the homonymous sea-deity was her parent according to some early myths.[77] One myth relates the foster father relationship of this Triton towards the half-orphan Athena, whom he raised alongside his own daughter Pallas.[78] Kerényi suggests that "Tritogeneia did not mean that she came into the world on any particular river or lake, but that she was born of the water itself; for the name Triton seems to be associated with water generally."[79][80] In Ovid's Metamorphoses, Athena is occasionally referred to as "Tritonia".

Another possible meaning may be "triple-born" or "third-born", which may refer to a triad or to her status as the third daughter of Zeus or the fact she was born from Metis, Zeus, and herself; various legends list her as being the first child after Artemis and Apollo, though other legends identify her as Zeus' first child.[81] Several scholars have suggested a connection to the Rigvedic god Trita,[82] who was sometimes grouped in a body of three mythological poets.[82] Michael Janda has connected the myth of Trita to the scene in the Iliad in which the "three brothers" Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades divide the world between them, receiving the "broad sky", the sea, and the underworld respectively.[83][84] Janda further connects the myth of Athena being born of the head (i. e. the uppermost part) of Zeus, understanding Trito- (which perhaps originally meant "the third") as another word for "the sky".[83] In Janda's analysis of Indo-European mythology, this heavenly sphere is also associated with the mythological body of water surrounding the inhabited world (cfr. Triton's mother, Amphitrite).[83]

Yet another possible meaning is mentioned in Diogenes Laertius' biography of Democritus, that Athena was called "Tritogeneia" because three things, on which all mortal life depends, come from her.[85]

Mythology

Birth

In the classical Olympian pantheon, Athena was regarded as the favorite daughter of Zeus, born fully armed from his forehead.[86][87][88][lower-alpha 8] The story of her birth comes in several versions.[89][90][91] The earliest mention is in Book V of the Iliad, when Ares accuses Zeus of being biased in favor of Athena because "autos egeinao" (literally "you fathered her", but probably intended as "you gave birth to her").[92][93]

In the version recounted by Hesiod in his Theogony, Zeus married the goddess Metis, who is described as the "wisest among gods and mortal men", and engaged in sexual intercourse with her.[94][95][93][96] After learning that Metis was pregnant, however, he became afraid that the unborn offspring would try to overthrow him, because Gaia and Ouranos had prophesied that Metis would bear children wiser than their father.[94][95][93][96] In order to prevent this, Zeus tricked Metis into letting him swallow her, but it was too late because Metis had already conceived.[94][97][93][96] A later account of the story from the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, written in the second century AD, makes Metis Zeus's unwilling sexual partner, rather than his wife.[98][99] According to this version of the story, Metis transformed into many different shapes in effort to escape Zeus,[98][99] but Zeus successfully raped her and swallowed her.[98][99]

After swallowing Metis, Zeus took six more wives in succession until he married his seventh and present wife, Hera.[96] Then Zeus experienced an enormous headache.[100][93][96] He was in such pain that he ordered someone (either Prometheus, Hephaestus, Hermes, Ares, or Palaemon, depending on the sources examined) to cleave his head open with the labrys, the double-headed Minoan axe.[101][93][102][99] Athena leaped from Zeus's head, fully grown and armed.[101][93][88][103] The "First Homeric Hymn to Athena" states in lines 9–16 that the gods were awestruck by Athena's appearance[104] and even Helios, the god of the sun, stopped his chariot in the sky.[104] Pindar, in his "Seventh Olympian Ode", states that she "cried aloud with a mighty shout" and that "the Sky and mother Earth shuddered before her."[105][104]

Hesiod states that Hera was so annoyed at Zeus for having given birth to a child on his own that she conceived and bore Hephaestus by herself,[96] but in Imagines 2. 27 (trans. Fairbanks), the third-century AD Greek rhetorician Philostratus the Elder writes that Hera "rejoices" at Athena's birth "as though Athena were her daughter also." The second-century AD Christian apologist Justin Martyr takes issue with those pagans who erect at springs images of Kore, whom he interprets as Athena: "They said that Athena was the daughter of Zeus not from intercourse, but when the god had in mind the making of a world through a word (logos) his first thought was Athena."[106] According to a version of the story in a scholium on the Iliad (found nowhere else), when Zeus swallowed Metis, she was pregnant with Athena by the Cyclops Brontes.[107] The Etymologicum Magnum[108] instead deems Athena the daughter of the Daktyl Itonos.[109] Fragments attributed by the Christian Eusebius of Caesarea to the semi-legendary Phoenician historian Sanchuniathon, which Eusebius thought had been written before the Trojan war, make Athena instead the daughter of Cronus, a king of Byblos who visited "the inhabitable world" and bequeathed Attica to Athena.[110][111]

Pallas Athena

Athena's epithet Pallas is derived either from πάλλω, meaning "to brandish [as a weapon]", or, more likely, from παλλακίς and related words, meaning "youth, young woman".[113] On this topic, Walter Burkert says "she is the Pallas of Athens, Pallas Athenaie, just as Hera of Argos is Here Argeie."[5] In later times, after the original meaning of the name had been forgotten, the Greeks invented myths to explain its origin, such as those reported by the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus and the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, which claim that Pallas was originally a separate entity, whom Athena had slain in combat.[114]

In one version of the myth, Pallas was the daughter of the sea-god Triton;[78] she and Athena were childhood friends, but Athena accidentally killed her during a friendly sparring match.[115] Distraught over what she had done, Athena took the name Pallas for herself as a sign of her grief.[115] In another version of the story, Pallas was a Gigante;[101] Athena slew him during the Gigantomachy and flayed off his skin to make her cloak, which she wore as a victory trophy.[101][12][116][117] In an alternative variation of the same myth, Pallas was instead Athena's father,[101][12] who attempted to assault his own daughter,[118] causing Athena to kill him and take his skin as a trophy.[119]

The palladion was a statue of Athena that was said to have stood in her temple on the Trojan Acropolis.[120] Athena was said to have carved the statue herself in the likeness of her dead friend Pallas.[120] The statue had special talisman-like properties[120] and it was thought that, as long as it was in the city, Troy could never fall.[120] When the Greeks captured Troy, Cassandra, the daughter of Priam, clung to the palladion for protection,[120] but Ajax the Lesser violently tore her away from it and dragged her over to the other captives.[120] Athena was infuriated by this violation of her protection.[112] Although Agamemnon attempted to placate her anger with sacrifices, Athena sent a storm at Cape Kaphereos to destroy almost the entire Greek fleet and scatter all of the surviving ships across the Aegean.[121]

Lady of Athens

In a founding myth reported by Pseudo-Apollodorus,[108] Athena competed with Poseidon for the patronage of Athens.[122] They agreed that each would give the Athenians one gift[122] and that Cecrops, the king of Athens, would determine which gift was better.[122] Poseidon struck the ground with his trident and a salt water spring sprang up;[122] this gave the Athenians access to trade and water.[123] Athens at its height was a significant sea power, defeating the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis[123]—but the water was salty and undrinkable.[123] In an alternative version of the myth from Vergil's Georgics,[108] Poseidon instead gave the Athenians the first horse.[122] Athena offered the first domesticated olive tree.[122][53] Cecrops accepted this gift[122] and declared Athena the patron goddess of Athens.[122] The olive tree brought wood, oil, and food,[123] and became a symbol of Athenian economic prosperity.[53][124] Robert Graves was of the opinion that "Poseidon's attempts to take possession of certain cities are political myths",[123] which reflect the conflict between matriarchal and patriarchal religions.[123]

Pseudo-Apollodorus[108] records an archaic legend, which claims that Hephaestus once attempted to rape Athena, but she pushed him away, causing him to ejaculate on her thigh.[126][51][127] Athena wiped the semen off using a tuft of wool, which she tossed into the dust,[126][51][127] impregnating Gaia and causing her to give birth to Erichthonius.[126][51][127] Athena adopted Erichthonius as her son and raised him.[126][127] The Roman mythographer Hyginus[108] records a similar story in which Hephaestus demanded Zeus to let him marry Athena since he was the one who had smashed open Zeus's skull, allowing Athena to be born.[126] Zeus agreed to this and Hephaestus and Athena were married,[126] but, when Hephaestus was about to consummate the union, Athena vanished from the bridal bed, causing him to ejaculate on the floor, thus impregnating Gaia with Erichthonius.[126]

The geographer Pausanias[108] records that Athena placed the infant Erichthonius into a small chest[128] (cista), which she entrusted to the care of the three daughters of Cecrops: Herse, Pandrosos, and Aglauros of Athens.[128] She warned the three sisters not to open the chest,[128] but did not explain to them why or what was in it.[128] Aglauros, and possibly one of the other sisters,[128] opened the chest.[128] Differing reports say that they either found that the child itself was a serpent, that it was guarded by a serpent, that it was guarded by two serpents, or that it had the legs of a serpent.[129] In Pausanias's story, the two sisters were driven mad by the sight of the chest's contents and hurled themselves off the Acropolis, dying instantly,[130] but an Attic vase painting shows them being chased by the serpent off the edge of the cliff instead.[130]

Erichthonius was one of the most important founding heroes of Athens[51] and the legend of the daughters of Cecrops was a cult myth linked to the rituals of the Arrhephoria festival.[51][131] Pausanias records that, during the Arrhephoria, two young girls known as the Arrhephoroi, who lived near the temple of Athena Polias, would be given hidden objects by the priestess of Athena,[132] which they would carry on their heads down a natural underground passage.[132] They would leave the objects they had been given at the bottom of the passage and take another set of hidden objects,[132] which they would carry on their heads back up to the temple.[132] The ritual was performed in the dead of night[132] and no one, not even the priestess, knew what the objects were.[132] The serpent in the story may be the same one depicted coiled at Athena's feet in Pheidias's famous statue of the Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon.[125] Many of the surviving sculptures of Athena show this serpent.[125]

Herodotus records that a serpent lived in a crevice on the north side of the summit of the Athenian Acropolis[125] and that the Athenians left a honey cake for it each month as an offering.[125] On the eve of the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, the serpent did not eat the honey cake[125] and the Athenians interpreted it as a sign that Athena herself had abandoned them.[125] Another version of the myth of the Athenian maidens is told in Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – 17 AD); in this late variant Hermes falls in love with Herse. Herse, Aglaulus, and Pandrosus go to the temple to offer sacrifices to Athena. Hermes demands help from Aglaulus to seduce Herse. Aglaulus demands money in exchange. Hermes gives her the money the sisters have already offered to Athena. As punishment for Aglaulus's greed, Athena asks the goddess Envy to make Aglaulus jealous of Herse. When Hermes arrives to seduce Herse, Aglaulus stands in his way instead of helping him as she had agreed. He turns her to stone.[133]

Patron of heroes

According to Pseudo-Apollodorus's Bibliotheca, Athena advised Argos, the builder of the Argo, the ship on which the hero Jason and his band of Argonauts sailed, and aided in the ship's construction.[135][136] Pseudo-Apollodorus also records that Athena guided the hero Perseus in his quest to behead Medusa.[137][138][139] She and Hermes, the god of travelers, appeared to Perseus after he set off on his quest and gifted him with tools he would need to kill the Gorgon.[139][140] Athena gave Perseus a polished bronze shield to view Medusa's reflection rather than looking at her directly and thereby avoid being turned to stone.[139][141] Hermes gave him an adamantine scythe to cut off Medusa's head.[139][142] When Perseus swung his blade to behead Medusa, Athena guided it, allowing his scythe to cut it clean off.[139][141] According to Pindar's Thirteenth Olympian Ode, Athena helped the hero Bellerophon tame the winged horse Pegasus by giving him a bit.[143][144]

In ancient Greek art, Athena is frequently shown aiding the hero Heracles.[145] She appears in four of the twelve metopes on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia depicting Heracles's Twelve Labors,[146][145] including the first, in which she passively watches him slay the Nemean lion,[145] and the tenth, in which she is shown actively helping him hold up the sky.[147] She is presented as his "stern ally",[148] but also the "gentle... acknowledger of his achievements."[148] Artistic depictions of Heracles's apotheosis show Athena driving him to Mount Olympus in her chariot and presenting him to Zeus for his deification.[147] In Aeschylus's tragedy Orestes, Athena intervenes to save Orestes from the wrath of the Erinyes and presides over his trial for the murder of his mother Clytemnestra.[149] When half the jury votes to acquit and the other half votes to convict, Athena casts the deciding vote to acquit Orestes[149] and declares that, from then on, whenever a jury is tied, the defendant shall always be acquitted.[150]

In The Odyssey, Odysseus' cunning and shrewd nature quickly wins Athena's favour.[151][136] For the first part of the poem, however, she largely is confined to aiding him only from afar, mainly by implanting thoughts in his head during his journey home from Troy. Her guiding actions reinforce her role as the "protectress of heroes," or, as mythologian Walter Friedrich Otto dubbed her, the "goddess of nearness," due to her mentoring and motherly probing.[152][137][153] It is not until he washes up on the shore of the island of the Phaeacians, where Nausicaa is washing her clothes that Athena arrives personally to provide more tangible assistance.[154] She appears in Nausicaa's dreams to ensure that the princess rescues Odysseus and plays a role in his eventual escort to Ithaca.[155] Athena appears to Odysseus upon his arrival, disguised as a herdsman;[156][157][151] she initially lies and tells him that Penelope, his wife, has remarried and that he is believed to be dead,[156] but Odysseus lies back to her, employing skillful prevarications to protect himself.[158][157] Impressed by his resolve and shrewdness, she reveals herself and tells him what he needs to know in order to win back his kingdom.[159][157][151] She disguises him as an elderly beggar so that he will not be recognized by the suitors or Penelope,[160][157] and helps him to defeat the suitors.[160][161][157] Athena also appears to Odysseus's son Telemachus.[162] Her actions lead him to travel around to Odysseus's comrades and ask about his father.[163] He hears stories about some of Odysseus's journey.[163] Athena's push for Telemachos's journey helps him grow into the man role, that his father once held.[164] She also plays a role in ending the resultant feud against the suitors' relatives. She instructs Laertes to throw his spear and to kill Eupeithes, the father of Antinous.

Athena and Heracles on an Attic red-figure kylix, 480–470 BC

Athena and Heracles on an Attic red-figure kylix, 480–470 BC

Silver coin showing Athena with Scylla decorated helmet and Heracles fighting the Nemean lion (Heraclea Lucania, 390-340 BC)

Silver coin showing Athena with Scylla decorated helmet and Heracles fighting the Nemean lion (Heraclea Lucania, 390-340 BC)

Punishment myths

The Gorgoneion appears to have originated as an apotropaic symbol intended to ward off evil.[165] In a late myth invented to explain the origins of the Gorgon,[166] Medusa is described as having been a young priestess who served in the temple of Athena in Athens.[167] Poseidon lusted after Medusa, and raped her in the temple of Athena,[167] refusing to allow her vow of chastity to stand in his way.[167] Upon discovering the desecration of her temple, Athena transformed Medusa into a hideous monster with serpents for hair whose gaze would turn any mortal to stone.[168]

In his Twelfth Pythian Ode, Pindar recounts the story of how Athena invented the aulos, a kind of flute, in imitation of the lamentations of Medusa's sisters, the Gorgons, after she was beheaded by the hero Perseus.[169] According to Pindar, Athena gave the aulos to mortals as a gift.[169] Later, the comic playwright Melanippides of Melos (c. 480-430 BC) embellished the story in his comedy Marsyas,[169] claiming that Athena looked in the mirror while she was playing the aulos and saw how blowing into it puffed up her cheeks and made her look silly, so she threw the aulos away and cursed it so that whoever picked it up would meet an awful death.[169] The aulos was picked up by the satyr Marsyas, who was later killed by Apollo for his hubris.[169] Later, this version of the story became accepted as canonical[169] and the Athenian sculptor Myron created a group of bronze sculptures based on it, which was installed before the western front of the Parthenon in around 440 BC.[169]

A myth told by the early third-century BC Hellenistic poet Callimachus in his Hymn 5 begins with Athena bathing in a spring on Mount Helicon at midday with one of her favorite companions, the nymph Chariclo.[127][170] Chariclo's son Tiresias happened to be hunting on the same mountain and came to the spring searching for water.[127][170] He inadvertently saw Athena naked, so she struck him blind to ensure he would never again see what man was not intended to see.[127][171][172] Chariclo intervened on her son's behalf and begged Athena to have mercy.[127][172][173] Athena replied that she could not restore Tiresias's eyesight,[127][172][173] so, instead, she gave him the ability to understand the language of the birds and thus foretell the future.[174][173][127]

.jpg)

The fable of Arachne appears in Ovid's Metamorphoses (8 AD) (vi.5–54 and 129–145),[175][176][177] which is nearly the only extant source for the legend.[176][177] The story does not appear to have been well known prior to Ovid's rendition of it[176] and the only earlier reference to it is a brief allusion in Virgil's Georgics, (29 BC) (iv, 246) that does not mention Arachne by name.[177] According to Ovid, Arachne (whose name means spider in ancient Greek[178]) was the daughter of a famous dyer in Tyrian purple in Hypaipa of Lydia, and a weaving student of Athena.[179] She became so conceited of her skill as a weaver that she began claiming that her skill was greater than that of Athena herself.[179][180] Athena gave Arachne a chance to redeem herself by assuming the form of an old woman and warning Arachne not to offend the deities.[175][180] Arachne scoffed and wished for a weaving contest, so she could prove her skill.[181][180]

Athena wove the scene of her victory over Poseidon in the contest for the patronage of Athens.[181][182][180] Athena's tapestry also depicted the 12 Olympian gods and defeat of mythological figures who challenged their authority.[183] Arachne's tapestry featured twenty-one episodes of the deities' infidelity,[181][182][180] including Zeus being unfaithful with Leda, with Europa, and with Danaë.[182] It represented the unjust and discrediting behavior of the gods towards mortals.[183] Athena admitted that Arachne's work was flawless,[181][180][182] but was outraged at Arachne's offensive choice of subject, which displayed the failings and transgressions of the deities.[181][180][182] Finally, losing her temper, Athena destroyed Arachne's tapestry and loom, striking it with her shuttle.[181][180][182] Athena then struck Arachne across the face with her staff four times.[181][180][182] Arachne hanged herself in despair,[181][180][182] but Athena took pity on her and brought her back from the dead in the form of a spider.[181][180][182]

Trojan War

The myth of the Judgement of Paris is mentioned briefly in the Iliad,[184] but is described in depth in an epitome of the Cypria, a lost poem of the Epic Cycle,[185] which records that all the gods and goddesses as well as various mortals were invited to the marriage of Peleus and Thetis (the eventual parents of Achilles).[184] Only Eris, goddess of discord, was not invited.[185] She was annoyed at this, so she arrived with a golden apple inscribed with the word καλλίστῃ (kallistēi, "for the fairest"), which she threw among the goddesses.[186] Aphrodite, Hera, and Athena all claimed to be the fairest, and thus the rightful owner of the apple.[186][127]

The goddesses chose to place the matter before Zeus, who, not wanting to favor one of the goddesses, put the choice into the hands of Paris, a Trojan prince.[186][127] After bathing in the spring of Mount Ida where Troy was situated, the goddesses appeared before Paris for his decision.[186] In the extant ancient depictions of the Judgement of Paris, Aphrodite is only occasionally represented nude, and Athena and Hera are always fully clothed.[187] Since the Renaissance, however, western paintings have typically portrayed all three goddesses as completely naked.[187]

All three goddesses were ideally beautiful and Paris could not decide between them, so they resorted to bribes.[186] Hera tried to bribe Paris with power over all Asia and Europe,[186][127] and Athena offered fame and glory in battle,[186][127] but Aphrodite promised Paris that, if he were to choose her as the fairest, she would let him marry the most beautiful woman on earth.[188][127] This woman was Helen, who was already married to King Menelaus of Sparta.[188] Paris selected Aphrodite and awarded her the apple.[188][127] The other two goddesses were enraged and, as a direct result, sided with the Greeks in the Trojan War.[188][127]

In Books V–VI of the Iliad, Athena aids the hero Diomedes, who, in the absence of Achilles, proves himself to be the most effective Greek warrior.[189][136] Several artistic representations from the early sixth century BC may show Athena and Diomedes,[189] including an early sixth-century BC shield band depicting Athena and an unidentified warrior riding on a chariot, a vase painting of a warrior with his charioteer facing Athena, and an inscribed clay plaque showing Diomedes and Athena riding in a chariot.[189] Numerous passages in the Iliad also mention Athena having previously served as the patron of Diomedes's father Tydeus.[190][191] When the Trojan women go to the temple of Athena on the Acropolis to plead her for protection from Diomedes, Athena ignores them.[112]

In Book XXII of the Iliad, while Achilles is chasing Hector around the walls of Troy, Athena appears to Hector disguised as his brother Deiphobus[192] and persuades him to hold his ground so that they can fight Achilles together.[192] Then, Hector throws his spear at Achilles and misses, expecting Deiphobus to hand him another,[193] but Athena disappears instead, leaving Hector to face Achilles alone without his spear.[193] In Sophocles's tragedy Ajax, she punishes Odysseus's rival Ajax the Great, driving him insane and causing him to massacre the Achaeans' cattle, thinking that he is slaughtering the Achaeans themselves.[194] Even after Odysseus himself expresses pity for Ajax,[195] Athena declares, "To laugh at your enemies - what sweeter laughter can there be than that?" (lines 78–9).[195] Ajax later commits suicide as a result of his humiliation.[195]

Classical art

Athena appears frequently in classical Greek art, including on coins and in paintings on ceramics.[196][197] She is especially prominent in works produced in Athens.[196] In classical depictions, Athena is usually portrayed standing upright, wearing a full-length chiton.[198] She is most often represented dressed in armor like a male soldier[197][198][7] and wearing a Corinthian helmet raised high atop her forehead.[199][7][197] Her shield bears at its centre the aegis with the head of the gorgon (gorgoneion) in the center and snakes around the edge.[166] Sometimes she is shown wearing the aegis as a cloak.[197] As Athena Promachos, she is shown brandishing a spear.[196][7][197] Scenes in which Athena was represented include her birth from the head of Zeus, her battle with the Gigantes, the birth of Erichthonius, and the Judgement of Paris.[196]

The Mourning Athena or Athena Meditating is a famous relief sculpture dating to around 470-460 BC[199][196] that has been interpreted to represent Athena Polias.[199] The most famous classical depiction of Athena was the Athena Parthenos, a now-lost 11.5 m (38 ft)[200] gold and ivory statue of her in the Parthenon created by the Athenian sculptor Phidias.[198][196] Copies reveal that this statue depicted Athena holding her shield in her left hand with Nike, the winged goddess of victory, standing in her right.[196] Athena Polias is also represented in a Neo-Attic relief now held in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,[199] which depicts her holding an owl in her hand[lower-alpha 9] and wearing her characteristic Corinthian helmet while resting her shield against a nearby herma.[199] The Roman goddess Minerva adopted most of Athena's Greek iconographical associations,[201] but was also integrated into the Capitoline Triad.[201]

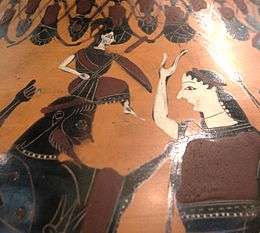

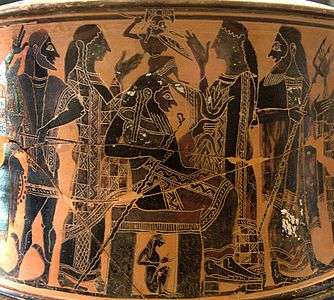

Attic black-figure exaleiptron of the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus (c. 570–560 BC) by the C Painter[196]

Attic black-figure exaleiptron of the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus (c. 570–560 BC) by the C Painter[196] Attic red-figure kylix of Athena Promachos holding a spear and standing beside a Doric column (c. 500-490 BC)

Attic red-figure kylix of Athena Promachos holding a spear and standing beside a Doric column (c. 500-490 BC)- Restoration of the polychrome decoration of the Athena statue from the Aphaea temple at Aegina, c. 490 BC (from the exposition "Bunte Götter" by the Munich Glyptothek)

Relief of Athena and Nike slaying the Gigante Alkyoneus (?) from the Gigantomachy Frieze on the Pergamon Altar (early second century BC)

Relief of Athena and Nike slaying the Gigante Alkyoneus (?) from the Gigantomachy Frieze on the Pergamon Altar (early second century BC) Classical mosaic from a villa at Tusculum, 3rd century AD, now at Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican

Classical mosaic from a villa at Tusculum, 3rd century AD, now at Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Athena portrait by Eukleidas on a tetradrachm from Syracuse,Sicily c. 400 BC

Athena portrait by Eukleidas on a tetradrachm from Syracuse,Sicily c. 400 BC Mythological scene with Athena (left) and Herakles (right), on a stone palette of the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, India

Mythological scene with Athena (left) and Herakles (right), on a stone palette of the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, India- Atena farnese, Roman copy of a Greek original from Phidias' circle, c. 430 AD, Museo Archeologico, Naples

Post-classical culture

Art and symbolism

Early Christian writers, such as Clement of Alexandria and Firmicus, denigrated Athena as representative of all the things that were detestable about paganism;[203] they condemned her as "immodest and immoral".[204] During the Middle Ages, however, many attributes of Athena were given to the Virgin Mary,[204] who, in fourth century portrayals, was often depicted wearing the Gorgoneion.[204] Some even viewed the Virgin Mary as a warrior maiden, much like Athena Parthenos;[204] one anecdote tells that the Virgin Mary once appeared upon the walls of Constantinople when it was under siege by the Avars, clutching a spear and urging the people to fight.[205] During the Middle Ages, Athena became widely used as a Christian symbol and allegory, and she appeared on the family crests of certain noble houses.[206]

During the Renaissance, Athena donned the mantle of patron of the arts and human endeavor;[207] allegorical paintings involving Athena were a favorite of the Italian Renaissance painters.[207] In Sandro Botticelli's painting Pallas and the Centaur, probably painted sometime in the 1480s, Athena is the personification of chastity, who is shown grasping the forelock of a centaur, who represents lust.[208][209] Andrea Mantegna's 1502 painting Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue uses Athena as the personification of Graeco-Roman learning chasing the vices of medievalism from the garden of modern scholarship.[210][209][211] Athena is also used as the personification of wisdom in Bartholomeus Spranger's 1591 painting The Triumph of Wisdom or Minerva Victorious over Ignorance.[201]

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Athena was used as a symbol for female rulers.[212] In his book A Revelation of the True Minerva (1582), Thomas Blennerhassett portrays Queen Elizabeth I of England as a "new Minerva" and "the greatest goddesse nowe on earth".[213] A series of paintings by Peter Paul Rubens depict Athena as Marie de' Medici's patron and mentor;[214] the final painting in the series goes even further and shows Marie de' Medici with Athena's iconography, as the mortal incarnation of the goddess herself.[214] The German sculptor Jean-Pierre-Antoine Tassaert later portrayed Catherine II of Russia as Athena in a marble bust in 1774.[201] During the French Revolution, statues of pagan gods were torn down all throughout France, but statues of Athena were not.[214] Instead, Athena was transformed into the personification of freedom and the republic[214] and a statue of the goddess stood in the center of the Place de la Revolution in Paris.[214] In the years following the Revolution, artistic representations of Athena proliferated.[215]

A statue of Athena stands directly in front of the Austrian Parliament Building in Vienna,[216] and depictions of Athena have influenced other symbols of western freedom, including the Statue of Liberty and Britannia.[216] For over a century, a full-scale replica of the Parthenon has stood in Nashville, Tennessee.[217] In 1990, the curators added a gilded forty-two-foot (12.5 m) tall replica of Phidias's Athena Parthenos, built from concrete and fiberglass.[217] The state seal of California bears the image of Athena kneeling next to a brown grizzly bear.[218] Athena has occasionally appeared on modern coins, as she did on the ancient Athenian drachma. Her head appears on the $50 1915-S Panama-Pacific commemorative coin.[219]

Pallas and the Centaur (c. 1482) by Sandro Botticelli

Pallas and the Centaur (c. 1482) by Sandro Botticelli_02.jpg)

Athena Scorning the Advances of Hephaestus (c. 1555-1560) by Paris Bordone

Athena Scorning the Advances of Hephaestus (c. 1555-1560) by Paris Bordone Minerva Victorious over Ignorance (c. 1591) by Bartholomeus Spranger

Minerva Victorious over Ignorance (c. 1591) by Bartholomeus Spranger Maria de Medici (1622) by Peter Paul Rubens, showing her as the incarnation of Athena[214]

Maria de Medici (1622) by Peter Paul Rubens, showing her as the incarnation of Athena[214]_Peace_and_War_(1629).jpg) Minerva Protecting Peace from Mars (1629) by Peter Paul Rubens

Minerva Protecting Peace from Mars (1629) by Peter Paul Rubens Pallas Athena (c. 1655) by Rembrandt

Pallas Athena (c. 1655) by Rembrandt Minerva Revealing Ithaca to Ulysses (fifteenth century) by Giuseppe Bottani

Minerva Revealing Ithaca to Ulysses (fifteenth century) by Giuseppe Bottani

The Combat of Mars and Minerva (1771) by Joseph-Benoît Suvée

The Combat of Mars and Minerva (1771) by Joseph-Benoît Suvée Minerva Fighting Mars (1771) by Jacques-Louis David

Minerva Fighting Mars (1771) by Jacques-Louis David Minerva of Peace mosaic in the Library of Congress

Minerva of Peace mosaic in the Library of Congress Athena on the Great Seal of California

Athena on the Great Seal of California

Modern interpretations

One of Sigmund Freud's most treasured possessions was a small, bronze sculpture of Athena, which sat on his desk.[220] Freud once described Athena as "a woman who is unapproachable and repels all sexual desires - since she displays the terrifying genitals of the Mother."[221] Feminist views on Athena are sharply divided;[221] some feminists regard her as a symbol of female empowerment,[221] while others regard her as "the ultimate patriarchal sell out... who uses her powers to promote and advance men rather than others of her sex."[221] In contemporary Wicca, Athena is venerated as an aspect of the Goddess[222] and some Wiccans believe that she may bestow the "Owl Gift" ("the ability to write and communicate clearly") upon her worshippers.[222] Due to her status as one of the twelve Olympians, Athena is a major deity in Hellenismos,[223] a Neopagan religion which seeks to authentically revive and recreate the religion of ancient Greece in the modern world.[224]

Athena is a natural patron of universities: At Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania a statue of Athena (a replica of the original bronze one in the arts and archaeology library) resides in the Great Hall.[225] It is traditional at exam time for students to leave offerings to the goddess with a note asking for good luck,[225] or to repent for accidentally breaking any of the college's numerous other traditions.[225] Pallas Athena is the tutelary goddess of the international social fraternity Phi Delta Theta.[226] Her owl is also a symbol of the fraternity.[226]

Genealogy

| Athena's family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Athenaeum (disambiguation)

- Ambulia, a Spartan epithet used for Athena, Zeus, and Castor and Pollux

Notes

- In other traditions, Athena's father is sometimes listed as Pallas the Giant, Cyclops Brontes, or Itonos the Daktyl.[1]

- /əˈθiːnə/; Attic Greek: Ἀθηνᾶ, Athēnâ, or Ἀθηναία, Athēnaía; Epic: Ἀθηναίη, Athēnaíē; Doric: Ἀθάνα, Athā́nā

- /əˈθiːniː/; Ionic: Ἀθήνη, Athḗnē

- /ˈpæləs/; Παλλάς Pallás

- "The citizens have a deity for their foundress; she is called in the Egyptian tongue Neith, and is asserted by them to be the same whom the Hellenes call Athena; they are great lovers of the Athenians, and say that they are in some way related to them." (Timaeus 21e.)

- Aeschylus, Eumenides, v. 292 f. Cf. the tradition that she was the daughter of Neilos: see, e. g. Clement of Alexandria Protr. 2.28.2; Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.59.

- "This sanctuary had been respected from early days by all the Peloponnesians, and afforded peculiar safety to its suppliants" (Pausanias, Description of Greece iii.5.6)

- Jane Ellen Harrison's famous characterization of this myth-element as, "a desperate theological expedient to rid an earth-born Kore of her matriarchal conditions" (Harrison 1922:302) has never been refuted nor confirmed.

- The owl's role as a symbol of wisdom originates in this association with Athena.

- According to Homer, Iliad 1.570–579, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312, Hephaestus was apparently the son of Hera and Zeus, see Gantz, p. 74.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 927–929, Hephaestus was produced by Hera alone, with no father, see Gantz, p. 74.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 183–200, Aphrodite was born from Uranus' severed genitals, see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

- According to Homer, Aphrodite was the daughter of Zeus (Iliad 3.374, 20.105; Odyssey 8.308, 320) and Dione (Iliad 5.370–71), see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

References

- Kerényi 1951, pp. 121–122.

- L. Day 1999, p. 39.

- Inc, Merriam-Webster (1995). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Merriam-Webster. p. 81]. ISBN 9780877790426.

- Deacy & Villing 2001.

- Burkert 1985, p. 139.

- Ruck & Staples 1994, p. 24.

- Powell 2012, p. 230.

- Beekes 2009, p. 29.

- Johrens 1981, pp. 438–452.

- Hurwit 1999, p. 14.

- Nilsson 1967, pp. 347, 433.

- Burkert 1985, p. 140.

- Puhvel 1987, p. 133.

- Kinsley 1989, pp. 141–142.

- Chadwick 1976, pp. 88–89.

- Ventris & Chadwick 1973, p. 126.

- Palaima 2004, p. 444.

- Burkert 1985, p. 44.

- KO Za 1 inscription, line 1.

- Best 1989, p. 30.

- Mylonas 1966, p. 159.

- Hurwit 1999, pp. 13–14.

- Fururmark 1978, p. 672.

- Nilsson 1950, p. 496.

- Harrison 1922:306. "Cfr. ibid., p. 307, fig. 84: Detail of a cup in the Faina collection". Archived from the original on 5 November 2004. Retrieved 6 May 2007..

- Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 92, 193.

- Puhvel 1987, pp. 133–134.

- Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 433.

- Penglase 1994, p. 235.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 20–21, 41.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 233–325.

- Cf. also Herodotus, Histories 2:170–175.

- Bernal 1987, pp. 21, 51 ff.

- Fritze 2009, pp. 221–229.

- Berlinerblau 1999, p. 93ff.

- Fritze 2009, pp. 221–255.

- Jasanoff & Nussbaum 1996, p. 194.

- Fritze 2009, pp. 250–255.

- Herrington 1955, pp. 11–15.

- Hurwit 1999, p. 15.

- Simon 1983, p. 46.

- Simon 1983, pp. 46–49.

- Herrington 1955, pp. 1–11.

- Burkert 1985, pp. 305–337.

- Herrington 1955, pp. 11–14.

- Schmitt 2000, pp. 1059–1073.

- Darmon 1992, pp. 114–115.

- Hansen 2004, pp. 123–124.

- Robertson 1992, pp. 90–109.

- Hurwit 1999, p. 18.

- Burkert 1985, p. 143.

- Goldhill 1986, p. 121.

- Garland 2008, p. 217.

- Hansen 2004, p. 123.

- Goldhill 1986, p. 31.

- Kerényi 1952.

- "Marinus of Samaria, The Life of Proclus or Concerning Happiness". tertullian.org. 1925. pp. 15–55.

Translated by Kenneth S. Guthrie (Para:30)

- Pilafidis-Williams 1998.

- Jost 1996, pp. 134–135.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece viii.4.8.

- Deacy 2008, p. 127.

- Burn 2004, p. 10.

- Burn 2004, p. 11.

- Burn 2004, pp. 10–11.

- Hubbard 1986, p. 28.

- Bell 1993, p. 13.

- Pausanias, i. 5. § 3; 41. § 6.

- John Tzetzes, ad Lycophr., l.c..

- Schaus & Wenn 2007, p. 30.

- "Life of Pericles 13,8". Plutarch, Parallel Lives. uchicago.edu. 1916.

The Parallel Lives by Plutarch published in Vol. III of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1916

- γλαυκῶπις in Liddell and Scott.

- γλαυκός in Liddell and Scott.

- ὤψ in Liddell and Scott.

- Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth (1895). A glossary of Greek birds. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 45.

- γλαύξ in Liddell and Scott.

- Nilsson 1950, pp. 491–496.

- Graves 1960, p. 55.

- Graves 1960, pp. 50–55.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 128.

- Τριτογένεια in Liddell and Scott.

- Hesiod, Theogony II, 886–900.

- Janda 2005, p. 289-298.

- Janda 2005, p. 293.

- Homer, Iliad XV, 187–195.

- "Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, BOOK IX, Chapter 7. DEMOCRITUS(? 460-357 B.C.)".

- Kerényi 1951, pp. 118–120.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 17–32.

- Penglase 1994, pp. 230–231.

- Kerényi 1951, pp. 118–122.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 17–19.

- Hansen 2004, pp. 121–123.

- Iliad Book V, line 880

- Deacy 2008, p. 18.

- Hesiod, Theogony 885-900, 929e-929t

- Kerényi 1951, pp. 118–119.

- Hansen 2004, pp. 121–122.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 119.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.3.6

- Hansen 2004, pp. 122–123.

- Kerényi 1951, pp. 119–120.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 120.

- Penglase 1994, p. 231.

- Hansen 2004, pp. 122–124.

- Penglase 1994, p. 233.

- Pindar, "Seventh Olympian Ode" lines 37–38

- Justin, Apology 64.5, quoted in Robert McQueen Grant, Gods and the One God, vol. 1:155, who observes that it is Porphyry "who similarly identifies Athena with 'forethought'".

- Gantz, p. 51; Yasumura, p. 89; scholia bT to Iliad 8.39.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 281.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 122.

- Oldenburg 1969, p. 86.

- I. P., Cory, ed. (1832). "The Theology of the Phœnicians from Sanchoniatho". Ancient Fragments. Translated by Cory. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010 – via Sacred-texts.com.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 68–69.

- Chantraine, s.v.; the New Pauly says the etymology is simply unknown

- New Pauly s.v. Pallas

- Graves 1960, p. 50.

- Deacy 2008, p. 51.

- Powell 2012, p. 231.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 120-121.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 121.

- Deacy 2008, p. 68.

- Deacy 2008, p. 71.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 124.

- Graves 1960, p. 62.

- Kinsley 1989, p. 143.

- Deacy 2008, p. 88.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 123.

- Hansen 2004, p. 125.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 125.

- Kerényi 1951, pp. 125–126.

- Kerényi 1951, p. 126.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 88–89.

- Deacy 2008, p. 89.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, X. Aglaura, Book II, 708–751; XI. The Envy, Book II, 752–832.

- Deacy 2008, p. 62.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.9.16

- Hansen 2004, p. 124.

- Burkert 1985, p. 141.

- Kinsley 1989, p. 151.

- Deacy 2008, p. 61.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2.37, 38, 39

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2.41

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2.39

- Deacy 2008, p. 48.

- Pindar, Olympian Ode 13.75-78

- Deacy 2008, pp. 64–65.

- Pollitt 1999, pp. 48–50.

- Deacy 2008, p. 65.

- Pollitt 1999, p. 50.

- Roman & Roman 2010, p. 161.

- Roman & Roman 2010, pp. 161–162.

- Jenkyns 2016, p. 19.

- W.F.Otto,Die Gotter Griechenlands(55-77).Bonn:F.Cohen,1929

- Deacy 2008, p. 59.

- de Jong 2001, p. 152.

- de Jong 2001, pp. 152–153.

- Trahman 1952, pp. 31–35.

- Burkert 1985, p. 142.

- Trahman 1952, p. 35.

- Trahman 1952, pp. 35–43.

- Trahman 1952, pp. 35–42.

- Jenkyns 2016, pp. 19–20.

- Murrin 2007, p. 499.

- Murrin 2007, pp. 499–500.

- Murrin 2007, pp. 499–514.

- Phinney 1971, pp. 445–447.

- Phinney 1971, pp. 445–463.

- Seelig 2002, p. 895.

- Seelig 2002, p. 895-911.

- Poehlmann 2017, p. 330.

- Morford & Lenardon 1999, p. 315.

- Morford & Lenardon 1999, pp. 315–316.

- Kugelmann 1983, p. 73.

- Morford & Lenardon 1999, p. 316.

- Edmunds 1990, p. 373.

- Powell 2012, pp. 233–234.

- Roman & Roman 2010, p. 78.

- Norton 2013, p. 166.

- ἀράχνη, ἀράχνης. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Powell 2012, p. 233.

- Harries 1990, pp. 64–82.

- Powell 2012, p. 234.

- Leach 1974, pp. 102–142.

- Roman, Luke; Roman, Monica (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology. Infobase Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 9781438126395.

- Walcot 1977, p. 31.

- Walcot 1977, pp. 31–32.

- Walcot 1977, p. 32.

- Bull 2005, pp. 346–347.

- Walcot 1977, pp. 32–33.

- Burgess 2001, p. 84.

- Iliad 4.390, 5.115-120, 10.284-94

- Burgess 2001, pp. 84–85.

- Deacy 2008, p. 69.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 69–70.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 59–60.

- Deacy 2008, p. 60.

- Aghion, Barbillon & Lissarrague 1996, p. 193.

- Hansen 2004, p. 126.

- Palagia & Pollitt 1996, p. 28-32.

- Palagia & Pollitt 1996, p. 32.

- "Athena Parthenos by Phidias". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Aghion, Barbillon & Lissarrague 1996, p. 194.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 145–149.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 141–144.

- Deacy 2008, p. 144.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 144–145.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 146–148.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 145–146.

- Randolph 2002, p. 221.

- Deacy 2008, p. 145.

- Brown 2007, p. 1.

- Aghion, Barbillon & Lissarrague 1996, pp. 193–194.

- Deacy 2008, p. 147-148.

- Deacy 2008, p. 147.

- Deacy 2008, p. 148.

- Deacy 2008, pp. 148–149.

- Deacy 2008, p. 149.

- Garland 2008, p. 330.

- "Symbols of the Seal of California". LearnCalifornia.org. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Swiatek & Breen 1981, pp. 201–202.

- Deacy 2008, p. 153.

- Deacy 2008, p. 154.

- Gallagher 2005, p. 109.

- Alexander 2007, pp. 31–32.

- Alexander 2007, pp. 11–20.

- Friedman 2005, p. 121.

- "Phi Delta Theta International - Symbols". phideltatheta.org. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

Bibliography

Ancient sources

- Apollodorus, Library, 3,180

- Augustine, De civitate dei xviii.8–9

- Cicero, De natura deorum iii.21.53, 23.59

- Eusebius, Chronicon 30.21–26, 42.11–14

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer; The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Lactantius, Divinae institutions i.17.12–13, 18.22–23

- Livy, Ab urbe condita libri vii.3.7

- Lucan, Bellum civile ix.350

Modern sources

- Aghion, Irène; Barbillon, Claire; Lissarrague, François (1996), "Minerva", Gods and Heroes of Classical Antiquity, Flammarion Infographic Guides, Paris, France and New York City, New York: Flammarion, pp. 192–194, ISBN 978-2-0801-3580-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alexander, Timothy Jay (2007), The Gods of Reason: An Authentic Theology for Modern Hellenismos (First ed.), Lulu Press, Inc., ISBN 978-1-4303-2763-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009), Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Leiden and Boston: Brill

- Bell, Robert E. (1993), Women of Classical Mythology: A Biographical Dictionary, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195079777CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernal, Martin (1987), Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 21, 51 ff

- Berlinerblau, Jacques (1999), Heresy in the University: The Black Athena Controversy and the Responsibilities of American Intellectuals, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, p. 93ff, ISBN 9780813525884

- Best, Jan (1989), Fred Woudhuizen (ed.), Lost Languages from the Mediterranean, Leiden, Germany et al.: Brill, p. 30, ISBN 978-9004089341

- Brown, Jane K. (2007), The Persistence of Allegory: Drama and Neoclassicism from Shakespeare to Wagner, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Penssylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-3966-9CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bull, Malcolm (2005), The Mirror of the Gods: How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan Gods, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-521923-4

- Burgess, Jonathan S. (2001), The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle, Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-6652-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-36281-9

- Burn, Lucilla (2004), Hellenistic Art: From Alexander the Great to Augustus, London, England: The British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-89236-776-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chadwick, John (1976), The Mycenaean World, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29037-1

- Darmon, Jean-Pierre (1992), Wendy Doniger (ed.), The Powers of War: Athena and Ares in Greek Mythology, translated by Danielle Beauvais, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press

- Deacy, Susan; Villing, Alexandra (2001), Athena in the Classical World, Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV

- Deacy, Susan (2008), Athena, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-30066-7

- de Jong, Irene J. F. (2001), A Narratological Commentary on the Odyssey, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-46844-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edmunds, Lowell (1990), Approaches to Greek Myth, Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-3864-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedman, Sarah (2005), Bryn Mawr College Off the Record, College Prowler, ISBN 978-1-59658-018-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2009), Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-Religions, London, England: Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-86189-430-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fururmark, A. (1978), "The Thera Catastrophe-Consequences for the European Civilization", Thera and the Aegean World I, London, England: Cambridge University Press

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Gallagher, Ann-Marie (2005), The Wicca Bible: The Definitive Guide to Magic and the Craft, New York City, New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., ISBN 978-1-4027-3008-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garland, Robert (2008), Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization, New York City, New York: Sterling, ISBN 978-1-4549-0908-8

- Goldhill, S. (1986), Reading Greek Tragedy (Aesch.Eum.737), Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

- Graves, Robert (1960) [1955], The Greek Myths, London, England: Penguin, ISBN 978-0241952740

- Hansen, William F. (2004), "Athena (also Athenê and Athenaia) (Roman Minerva)", Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, pp. 121–126, ISBN 978-0-19-530035-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harries, Byron (1990), "The spinner and the poet: Arachne in Ovid's Metamorphoses", The Cambridge Classical Journal, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 36: 64–82, doi:10.1017/S006867350000523X

- Harrison, Jane Ellen, 1903. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion.

- Herrington, C.J. (1955), Athena Parthenos and Athena Polias, Manchester, England: Manchester University Press

- Hubbard, Thomas K. (1986), "Pegasus' Bridle and the Poetics of Pindar's Thirteenth Olympian", in Tarrant, R. J. (ed.), Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 90, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-37937-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (1999), The Athenian Acropolis: History, Mythology, and Archaeology from the Neolithic Era to the Present, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-41786-0

- Janda, Michael (2005), Elysion. Entstehung und Entwicklung der griechischen Religion, Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen, ISBN 9783851247022

- Jasanoff, Jay H.; Nussbaum, Alan (1996), "Word games: the Linguistic Evidence in Black Athena" (PDF), in Mary R. Lefkowitz; Guy MacLean Rogers (eds.), Black Athena Revisited, The University of North Carolina Press, p. 194, ISBN 9780807845554

- Jenkyns, Richard (2016), Classical Literature: An Epic Journey from Homer to Virgil and Beyond, NewYork City, New York: Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group, ISBN 978-0-465-09797-5CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johrens, Gerhard (1981), Der Athenahymnus des Ailios Aristeides, Bonn, Germany: Habelt, pp. 438–452, ISBN 9783774918504

- Jost, Madeleine (1996), "Arcadian cults and myths", in Hornblower, Simon (ed.), Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press

- Kerényi, Karl (1951), The Gods of the Greeks, London, England: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-27048-6

- Kerényi, Karl (1952), Die Jungfrau und Mutter der griechischen Religion. Eine Studie uber Pallas Athene, Zurich: Rhein Verlag

- Kinsley, David (1989), The Goddesses' Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West, Albany, New York: New York State University Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-836-2

- Kugelmann, Robert (1983), The Windows of Soul: Psychological Physiology of the Human Eye and Primary Glaucoma, Plainsboro, New Jersey: Associated University Presses, ISBN 978-0-8387-5035-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- L. Day, Peggy (1999a), "Anat", in Toorn, Karel van der; Becking, Bob; Horst, Pieter Willem van der (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, pp. 36–39

- Leach, Eleanor Winsor (January 1974), "Ekphrasis and the Theme of Artistic Failure in Ovid's Metamorphoses", Ramus, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 3 (2): 102–142, doi:10.1017/S0048671X00004549

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (2006), Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morford, Mark P. O.; Lenardon, Robert J. (1999), Classical Mythology (sixth ed.), Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-514338-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murrin, Michael (Spring 2007), "Athena and Telemachus", International Journal of the Classical Tradition, Berlin, Germany: Springer, 13 (4): 499–514, doi:10.1007/BF02923022, JSTOR 30222174CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mylonas, G. (1966), Mycenae and the Mycenaean Age, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691035239

- Nilsson, Martin Persson (1950), The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion (second ed.), New York: Biblo & Tannen, ISBN 978-0-8196-0273-2

- Nilsson, Martin Persson (1967), Die Geschichte der griechischen Religion, München, Germany: C. F. Beck

- Norton, Elizabeth (2013), Aspects of Ecphrastic Technique in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4438-4271-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oldenburg, Ulf (1969), The Conflict Between El and Ba'al in Canaanite Religion, Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. BrillCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palagia, Olga; Pollitt, J. J. (1996), Personal Styles in Greek Sculpture, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65738-9