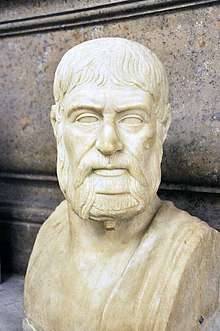

Pausanias (general)

Pausanias (Greek: Παυσανίας; died c. 470 BC) was a Spartan regent, general, and war leader for the Greeks who was suspected of conspiring with the Persian king, Xerxes I, during the Greco-Persian Wars. What is known of his life is largely according to Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, together with a handful of other classical sources.

Spartan lineage

As son of the regent Cleombrotus and nephew of the warrior king, Leonidas I, Pausanias was a scion of the Spartan royal house of the Agiads but not in the direct line of succession. After Leonidas' death, while the king's son Pleistarchus was still in his minority, Pausanias served as regent of Sparta. Pausanias was also the father of Pleistoanax who later became king. Other sons were Cleomenes and Nasteria.

War service

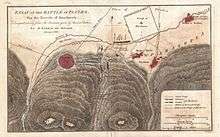

Pausanias was leader of the Hellenic League created to resist the Persian invasion. He led the Greeks in their victory over Mardonius and the Persians at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC.[1]. While the latter is sometimes seen as a chaotic soldiers battle,[2] others see evidence of both strategic and tactical skill on the part of Pausanias in delaying the engagement until the point where Spartan armour and discipline could have maximum impact.[3] Herodotus concluded that "Pausanias the son of Cleombrotus and grandson of Anaxandridas won the most glorious victory of any known to us".[4]

After the victories at Plataea and the Battle of Mycale, the Spartans lost interest in liberating the Greek cities of Asia Minor until it became clear that Athens would dominate the League in Sparta's absence. Sparta then sent Pausanias back to command the Greek military.

Suspected pact with Persia

In 478 BC Pausanias was suspected of conspiring with the Persians and was recalled to Sparta; however he was acquitted and then left Sparta of his own accord, taking a trireme from the town of Hermione. After capturing Byzantium the previous year, Pausanias was alleged to have released some of the prisoners of war who were friends and relations of the king of Persia. However, Pausanias argued that the prisoners had escaped. He allegedly sent a letter via Gongylos of Eretria to Xerxes, son of Darius, saying that he wished to help him and bring Sparta and the rest of Greece under Persian control. In return, he wished to marry the king's daughter. After Xerxes replied agreeing to his plans, Pausanias started to adopt Persian customs and dress like a Persian aristocrat.[5]

According to Thucydides and Plutarch[6] many Hellenic League allies joined the Athenian side because of Pausanias' arrogance and high-handedness. The Spartans recalled him once again, and Pausanias fled to Kolonai in the Troad before returning to Sparta as he did not wish to be suspected of Persian sympathies. On his arrival in Sparta, the ephors had him imprisoned, but he was later released. Nobody had enough evidence to convict him of disloyalty, even though some helots gave evidence that he had offered certain helots their freedom if they joined him in revolt. However one of the messengers that Pausanias had been using to communicate with Xerxes to betray the Greeks provided written evidence (a letter stating Pausanias' intentions) to the Spartan ephors that they needed to formally prosecute Pausanias.[7]

It is important to note, however, that our evidence comes from sources uniformly hostile to Pausanias: Athenians because they wished him removed from Greek command,[8] ; Spartans because of his innovatory views on freeing the Helots.[9]

Death

The ephors planned to arrest Pausanias in the street, but he was warned of their plans and escaped to the temple of Athena of the Brazen House. The ephors surrounded the temple, put sentries outside the entrances and proceeded to starve him out. When Pausanias was on the brink of death by starvation they carried him out, and he died soon afterwards.[10] Thus Pausanias did not die within the sanctuary of the temple, which would have been an act of ritual pollution.

According to Polyaenus, Pausanias took refuge in the temple of Athena Chalcioeca (Ancient Greek: Ἀθηνᾶς τῆς Χαλκιοίκου: of Athena of the Brass or Brazen House, the shrine of Athena at Sparta, as mentioned above). His mother Theano (Ancient Greek: Θεανὼ) immediately went there, and laid a brick, which she carried with her, at the door saying: "Unworthy to be a Spartan, you are not my son", (According to 1.1). The Lacedemonians admired her braveness and intelligence. They then blocked up the doorway with bricks, without forcing the suppliant from the temple.[11]

See also

Notes

- Herodotus, Historia 9

- J Boardman ed., The Oxford History of the Classical World (Oxford 1991) p. 48

- A R Burn, Persia and the Greeks (Stanford 1984) pp. 533–39

- R Waterfield trans, Herodotus: The Histories (Oxford 2008) p. 567

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponesian War 1.128–130

- Plutarch, Cimon 6 and Aristeides 23

- Thucydides I.133 s:History of the Peloponnesian War/Book 1#Second Congress at Lacedaemon - Preparations for War and Diplomatic Skirmishes - Cylon - Pausanias - Themistocles

- R Waterfield trans, Herodotus: The Histories (Oxford 2008) p. 731

- A R Burn, Persia and the Greeks (Stanford 1984) pp. 543, 565

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponesian War 1.134

- Polyaenus, Strategems, § 8.51.1