Paros

Paros (/ˈpɛərɒs/; Greek: Πάρος; Venetian: Paro) is a Greek island in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about 8 kilometres (5 miles) wide.[2] It lies approximately 150 km (93 miles) south-east of Piraeus. The Municipality of Paros includes numerous uninhabited offshore islets totaling 196.308 square kilometres (75.795 sq mi) of land.[3] Its nearest neighbor is the municipality of Antiparos, which lies to its southwest. In ancient Greece, the city-state of Paros was located on the island.[4]

Paros Πάρος | |

|---|---|

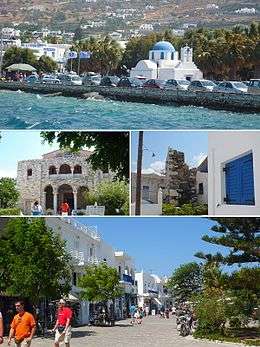

From top left: Parikia, Panagia Ekatontapiliani, the Frankish Castle and a typical Paros street | |

Flag  Seal | |

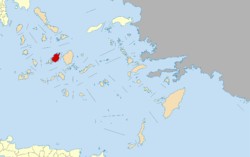

Paros Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 37°4′N 25°12′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | South Aegean |

| Regional unit | Paros |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 196.3 km2 (75.8 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 724 m (2,375 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 13,715 |

| • Municipality density | 70/km2 (180/sq mi) |

| Community | |

| • Population | 6,058 (2011) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 844 00 |

| Area code(s) | 22840 |

| Vehicle registration | EM |

| Website | www.paros.gr |

Historically, Paros was known for its fine white marble, which gave rise to the term "Parian" to describe marble or china of similar qualities.[5] Today, abandoned marble quarries and mines can be found on the island, but Paros is primarily known as a popular tourist spot.

Geography

Paros' geographic co-ordinates are 37° N. latitude, and 25° 10' E. longitude.[2] The area is 165 km2 (64 sq mi). Its greatest length from N.E. to S.W. is 21 km (13 mi), and its greatest breadth 16 km (10 mi).[2] The island is of a round, plump-pear shape, formed by a single mountain (724 m (2,375 ft)) sloping evenly down on all sides to a maritime plain, which is broadest on the north-east and south-west sides.[2] The island is composed of marble, though gneiss and mica-schist are to be found in a few places.[2] To the west of Paros lies its smaller sister island Antiparos. At its narrowest, the channel between the two islands is less than 2 km (1 mi) wide. A car-carrying shuttle-ferry operates all day (to and from Pounda, 5 km (3 mi) south of Parikia). In addition a dozen smaller islets surround Paros.

Paros has numerous beaches including Golden Beach (Chrissí Aktí) near Drios on the east coast, at Pounda, Logaras, Piso Livadi, Naousa Bay, Parikia and Agia Irini. The constant strong wind in the strait between Paros and Naxos makes it a favoured windsurfing location.

Islands

- Gaiduronisi – north of Xifara

- Portes Island – west of the town of Paros

- Tigani Island – southwest of Paros

- Drionisi – southeast of Paros

History

Antiquity

The story that Paros of Parrhasia colonized the island with Arcadians[6] is an etymological fiction of the type that abounds in Greek legends. Ancient names of the island are said to have been Plateia (or Pactia), Demetrias, Strongyle (meaning round, due to the round shape of the island), Hyria, Hyleessa, Minoa and Cabarnis.[2][7]

The island later received from Athens a colony of Ionians[8] under whom it attained a high degree of prosperity. It sent out colonies to Thasos[9] and Parium on the Hellespont. In the former colony, which was planned in the 15th or 18th Olympiad, the poet Archilochus,[10] a native of Paros, is said to have taken part. As late as 385 BC the Parians, in conjunction with Dionysius of Syracuse, founded a colony on the Illyrian island of Pharos[2] (Hvar).[11]

Shortly before the Persian War, Paros seems to have been a dependency of Naxos.[2][12] In the first Greco-Persian War (490 BC), Paros sided with the Persians and sent a trireme to Marathon to support them. In retaliation, the capital was besieged by an Athenian fleet under Miltiades, who demanded a fine of 100 talents.[2] But the town offered a vigorous resistance, and the Athenians were obliged to sail away after a siege of 26 days, during which they had wasted the island.[2] It was at a temple of Demeter Thesmophoros in Paros that Miltiades received the wound from which he died.[2][13] By means of an inscription, Ross was able to identify the site of the temple; it lies, as Herodotus suggests, on a low hill beyond the boundary of the town.[2]

Paros also sided with shahanshah Xerxes I of Persia against Greece in the second Greco-Persian War (480–479 BC), but, after the battle of Artemisium, the Parian contingent remained inactive at Kythnos as they watched the progression of events.[2][14] For their support of the Persians, the islanders were later punished by the Athenian war leader Themistocles, who exacted a heavy fine.[2][15]

Under the Delian League, the Athenian-dominated naval confederacy (477–404 BC), Paros paid the highest tribute of the island members: 30 talents annually, according to the estimate of Olympiodorus (429 BC).[2][16] This implies that Paros was one of the wealthiest islands in the Aegean. Little is known about the constitution of Paros, but inscriptions seem to show that it was modeled on the Athenian democracy, with a boule (senate) at the head of affairs.[2][17] In 410 BC, Athenian general Theramenes discovered that Paros was governed by an oligarchy; he deposed the oligarchy and restored the democracy.[18] Paros was included in the second Athenian confederacy (the Second Athenian League 378–355 BC). In c. 357 BC, along with Chios, it severed its connection with Athens.

From the inscription of Adule, it is understood that the Cyclades, which are presumed to include Paros, were subjected to the Ptolemies, the Hellenistic dynasty (305–30 BC) that ruled Egypt.[2] Paros then became part of the Roman Empire and later of the Byzantine Empire, its Greek-speaking successor state.

Crusades

In 1204, the soldiers of the Fourth Crusade seized Constantinople and overthrew the Byzantine Empire. Although a residual Byzantine state known as the Empire of Nicaea survived the Crusader onslaught and eventually recovered Constantinople (1261), many of the original Byzantine territories, including Paros, were lost permanently to the crusading powers. Paros became subject to the Duchy of the Archipelago, a fiefdom made up of various Aegean islands ruled by a Venetian duke as nominal vassal of a succession of crusader states. In practice, however, the duchy was always a client state of the Republic of Venice.

Ottoman Era and independence

In 1537, Paros was conquered by the Ottoman Turks and remained under the Ottoman Empire until the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829). During the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) in 1770–1775 Naoussa Bay was the home base for the Russian Archipelago Squadron of Count Alexey Orlov. Under the Treaty of Constantinople (1832), Paros became part of the newly independent Kingdom of Greece, the first time the Parians had been ruled by fellow Greeks for over six centuries. At this time, Paros became the home of a heroine of the nationalist movement, Manto Mavrogenous, who had both financed and fought in the war for independence. Her house, near Ekatontapiliani church, is today a historical monument.

On 26 September 2000 the ferry MS Express Samina collided with the Portes islets off the bay of Parikia, killing 82 of those on board.[19]

Parikia

The capital, Parikia, situated on a bay on the north-west side of the island, occupies the site of the ancient capital Paros.[2] Parikía harbour is a major hub for Aegean islands ferries and catamarans, with several sailings each day for Piraeus, the port of Athens, Heraklion, the capital of Crete, and other islands such as Naxos, Ios, Mykonos, and Santorini.

In Parikia town, houses are built and decorated in the traditional Cycladic style, with flat roofs, whitewash walls and blue-painted doors and window frames and shutters. Shadowed by luxuriant vines, and surrounded by gardens of oranges and pomegranates,[2] the houses give the town a picturesque aspect. Above the central stretch of the seafront road, are the remains of a medieval castle, built almost entirely of the marble remains[2] of an ancient temple dedicated to Apollo. Similar traces of antiquity, in the shape of bas-reliefs, inscriptions, columns, and so on, are numerous. On a hillside in the southern outskirts of Parikia on the left of the Parikia – Alyki road are the remains of a temple dedicated to Asclepius. In addition, close to the modern harbour, the remains of an ancient cemetery are visible, having been discovered recently during non-archaeological excavations.

Back from the port, around 400 m left of Parikia's main square, is the town's principal church, the Panagia Ekatontapiliani, literally meaning "church of the hundred doors". Its oldest features almost certainly predate the adoption of Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire in 391. It is said to have been founded by the mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (ruled 306–337), Saint Helen, during her pilgrimage to the Holy Land. There are two adjoining chapels, one of very early form, and also a baptistery with a cruciform font.[2]

Parikia town has a small but interesting archaeological museum housing some of the many finds from sites in Paros. The best pieces, however, are in the Athens National Archaeological Museum. The Paros museum contains a fragment of the Parian Chronicle, a remarkable chronology of ancient Greece. Inscribed in marble, its entries give time elapsed between key events from the most distant past (1500 BC) down to 264 BC.[20]

Other settlements

_Village_View.jpg)

On the north side of the island is the bay of Naoussa (Naussa) or Agoussa, which provides a safe and spacious harbour. In ancient times it was closed by a chain or boom. Another good harbour is that of Drios on the south-east side, where the Turkish fleet used to anchor on its annual voyage through the Aegean[2] during the period of Ottoman rule over Paros (1537–1832).

The three villages of Dragoulas, Mármara and Tsipidos, situated on an open plain on the eastern side of the island, and rich in remains of antiquity, probably occupy the site of an ancient town.[2] They are known together as the "villages of Kephalos" after the steep and lofty hill of Kephalos.[2] On this hilltop stands the monastery of Agios Antonios (St. Anthony). Around it are the ruins of a medieval castle which belonged in the late Middle Ages to the Venetian noble family of the Venieri.[2] They gallantly but vainly defended it against the Turkish admiral Barbarossa in 1537.

Another settlement on the island Paros is Lefkes (Λεύκες). Lefkes is an inland mountain village 10 km (6 mi) away from Parikia. In the late 19th century, Lefkes was the center of the municipality of Iria which belonged to the Province of Naxos until 1912. The name of the municipality Iria was one of the ancient names of Paros. Lefkes was the capital of the municipality Iria which included the villages Angyria or Ageria, Aliki, Aneratzia, Vounia, Kamari, Campos, Langada, Maltes and Marathi. Iria became Lefkes Community following the law enforcement DNZ/1912 "On Municipalities". At that time, the village managed to achieve great economic development. In the 1970s many residents moved to Athens, Maroussi and Melissia due to urbanization. However, the last few years, tourism presented to be a new source of income for the locals that led to the reconstruction of homes and landscaping for a peaceful and sweet life. Lefkes became part of the municipality of Paros in the Kapodistrias local government reform. In the latest census (2011) the population numbered 545 inhabitants.

Marble quarries

Parian marble, which is white and translucent, with a coarse grain and a very beautiful texture, was the chief source of wealth for the island.[2] The celebrated marble quarries lie on the northern side of the mountain anciently known as Marathi (afterwards Capresso), a little below a former convent of St Mina.[2] The marble, which was exported from the 6th century BC onwards, was used by Praxiteles and other great Greek sculptors. It was obtained by means of subterranean quarries driven horizontally or at a descending angle into the rock.[2] The marble thus quarried by lamplight was given the name of Lychnites, Lychneus (from lychnos, a lamp), or Lygdos.[2][21] Several of these tunnels are still to be seen.[2] At the entrance to one of them is a bas-relief dedicated to Pan and the nymphs.[2] Several attempts to work the marble have been made in modern times, but it has not been exported in any great quantities.[2] The major part of the remaining white marble is now state-owned and, like its Pentelic counterpart, is only used for archaeological restorations.

Notable people

- Ancient

- Agoracritus (5th century BC), sculptor

- Archilochus (c. 680 BC–c. 645 BC), lyric poet

- Scopas (c. 395–350 BC), sculptor and architect

- Theoctiste of Lesbos (9th century), hermit saint

- Thrasymedes (4th century BC), sculptor

- Thymaridas (c. 400 BC–350 BC), mathematician

- Modern

- Nurbanu Sultan (Cecilia Venier-Baffo) (1525–1583) mother of Ottoman Sultan Murad III

- Vassilis Argyropoulos (1894–1953) actor

- Nicholas Mavrogenes (1738–1790), prince of Wallachia

- Athanasius Parios (1721/22–1813), theologian

- Manto Mavrogenous (1796–1848), heroine in the Greek War of Independence

- Yiannis Ragousis (1965–), politician

- Yiannis Parios (1946-), musician

See also

- Communities of the Cyclades

- Aegean Center for the Fine Arts

References

- Notes

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 860–861.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- "Parian – definition of Parian by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- Heraclides De rebus publicis 8

- Stephanos Byz.

- Schol. Dionysius Periegetes 525; Herodian I.171

- Thucydides Peloponnesian War IV.104; Strabo Geography 487

- Zafeiropouloy F., and A., Agelarakis “Warriors of Paros”, Archaeology 58.1(2005): 30–35.

- Diodorus Siculus XV.13

- Herodotus Histories V.31

- Herodotus op.cit. VI.133–136

- Herodotus op.cit. VIII.67

- Herodotus op.cit. VIII.112

- Olympiodorus 88.4

- Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum 2376–2383; Ross, Inscr. med. II.147, 148

- Diodorus Siculus XIII.47

- "Ferry Disaster off Paros". Greek Island Hopping. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2011. ()

- Inscriptiones Graecae XII.100 seqq.

- Pliny the Elder Historia Naturalis XXXVI. 5, 14; Plato Eryxias, 400 D; Athenodorus V.205 f; Diodorus Siculus 2.52

- Sources

- Clarke Travels III (London, 1814)

- de Tournefort, J.R. Voyage du Levant I.232 seqq. (Lyon, 1717)

- Leake, William Martin, Travels in Northern Greece III.84 seqq. (London, 1835)

External links

- Website of the municipality of Paros

- Moving Postcards Paros

- Church of Ekatontapyliani (Church of a Hundred Doors)