Enna

Enna (Italian pronunciation: [ˈɛnna] (![]()

Enna | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Enna | |

.jpg) Panorama of Enna | |

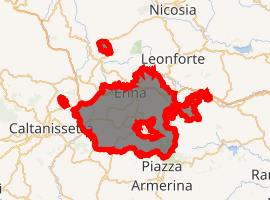

.svg.png) Enna in the Province of Enna | |

Location of Enna

| |

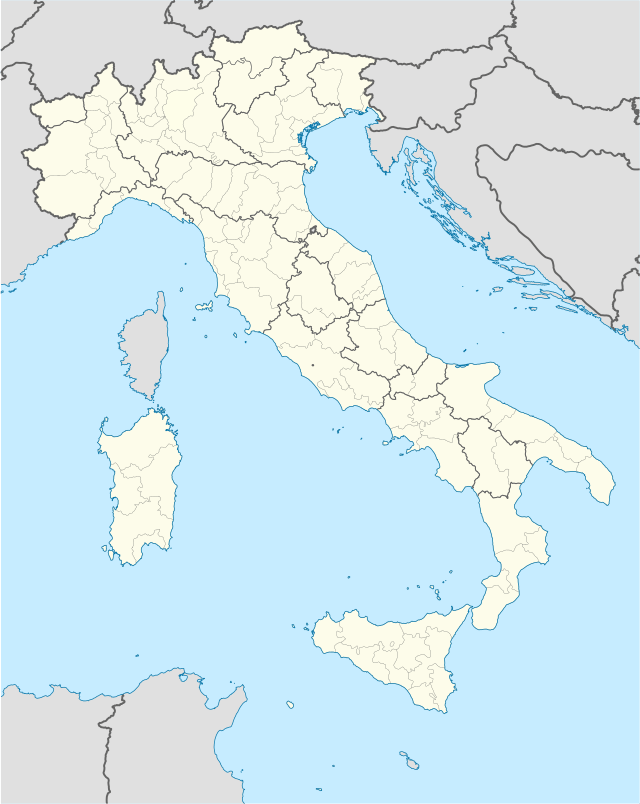

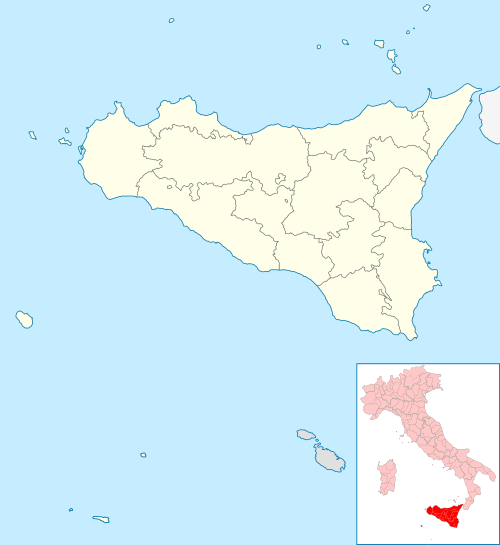

Enna Location of Enna in Italy  Enna Enna (Sicily) | |

| Coordinates: 37°33′48″N 14°16′34″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Sicily |

| Province | Enna (EN) |

| Frazioni | Enna Bassa, Pergusa, Borgo Cascino, Calderari, Bondo Ennate |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Maurizio Dipietro |

| Area | |

| • Total | 357 km2 (138 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 931 m (3,054 ft) |

| Population (30 November 2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 27,268 |

| • Density | 76/km2 (200/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Ennesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 94100, 94100 |

| Dialing code | 0935 |

| Patron saint | SS. Mary of Visitation |

| Saint day | July 2 |

| Website | Official website |

At 931 m (3,054 ft) above sea level, Enna is the highest Italian provincial capital.

History

Enna is situated near the center of the island; whence the Roman writer Cicero called it Mediterranea maxime, reporting that it was within a day's journey of the nearest point on all the three coasts. The peculiar situation of Enna is described by several ancient authors, and is one of the most remarkable in Sicily. The ancient city was placed on the level summit of a gigantic hill, surrounded on all sides with precipitous cliffs almost wholly inaccessible. The few paths were easily defended, and the city was abundantly supplied with water which gushes from the face of the rocks on all sides. With a plain or table land of about 5 km in circumference on the summit, it formed one of the strongest natural fortresses in the world.

Prehistoric

Archaeological excavations have revealed artifacts dating from the 14th century BC, proving human presence in the area since Neolithic times. A settlement from before the 11th century BC, assigned by some to the Sicanians, has been identified at the top of the hill; later it was a center of the Sicels.

In historical times, Enna became renowned in Sicily and Italy for the cult of the goddess Demeter (the Roman Ceres). Her grove was known as the umbilicus Siciliae ("The navel of Sicily"). Ceres' temple in Henna was a famed site of worship.[3]

The origin of the toponym Henna remains obscure.

Classical period

Dionysius I of Syracuse repeatedly attempted to take over Enna. At first he encouraged Aeimnestus, a citizen of Enna, to seize the sovereign power. Afterward Dionysius I turned against him and assisted the Ennaeans to get rid of their despot. But it was not till a later period that, after repeated expeditions against the neighbouring Sicilian cities, Dionysius took control of the city by betrayal.

Agathocles later controlled Enna. When the Agrigentines under Xenodicus began to proclaim the restoration of the other cities of Sicily to freedom, the Ennaeans were the first to join their standard, and opened their gates to Xenodicus, 309 BC. Accounts of the First Punic War repeatedly refer to Enna; it was taken first by the Carthaginians under Hamilcar, and subsequently recaptured by the Romans, but in both instances by treachery and not by force.

In the Second Punic War, while Marcellus was engaged in the siege of Syracuse (214 BC), Enna became the scene of a fearful massacre. The defection of several Sicilian towns from Rome had alarmed Pinarius the governor of Enna. In order to forestall any treachery, he used the Roman garrison to kill the citizens, whom he had gathered in the theater, and killed them all. The soldiers were allowed to plunder the city.

Eighty years later Enna was the center of the First Servile War in Sicily (134 BC-132 BC), which erupted under the lead of Eunus, a former slave. His forces took over Enna. It was the last place that held out against the proconsul Rupilius, and was at length betrayed into his hands. According to Strabo, the city suffered much damage after the Romans regained control. He believed this was the start of its decline.

Cicero referred to it repeatedly in a way to suggest that it was still a flourishing municipal town: it had a fertile territory, well-adapted for the growth of cereal grains, and was diligently cultivated till it was rendered almost desolate by the exactions of Verres. From this time little is known about Enna: Strabo speaks of it as still inhabited, though by a small population, in his time: and the name appears in Pliny among the municipal towns of Sicily, as well as in Ptolemy and the Itineraries.

When the Roman Empire was divided in 395AD, Sicily became part of the Western Roman Empire. The noted senatorial family of the Nicomachi had estates in Sicily. Around 408 the politician and grammarian Nicomachus Flavianus worked on an edition of the first 10 books of Livy during a stay on his estate in Enna. This was recorded in the subscriptions of the manuscripts of Livy.

Post-Roman

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Enna flourished throughout the Middle Ages as an important Byzantine stronghold. In 859, in the course of the Islamic conquest of Sicily, after several attempts and a long siege, the town was taken by Muslim troops, who entered one by one through a sewer to breach the town's defenses. Afterwards, 8,000 residents of the city were massacred by Muslim forces.[4] The Arabic name for the city, Qaṣr Yānih (قصر يانه, "Fort of John"), was a combination of qaṣr (a corruption of the Latin castrum, "fortress"), and a corruption of Henna. The city retained its name in the local dialect of Sicilian as Castru Janni (Italianized as Castrogiovanni), until Benito Mussolini ordered renaming in 1927.

The Normans captured Enna in 1087. Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily, established a summer residence here, which is now called the Torre di Federico ("Frederick Tower"). Troops of North Italian soldiers,[5] from regions such as Lombardy, Piedmont, Liguria and Emilia-Romagna, came to settle in the city and neighbouring towns such as Nicosia and Piazza Armerina. Gallo-Italic dialects are still spoken in these areas, dating from this early occupation.

Enna had a prominent role in the Sicilian Vespers that led to the Aragonese conquest of Sicily, and thenceforth enjoyed a short communal autonomy. King Frederick III of Sicily favored it and embellished the city; it suffered a period of decay under the Spanish domination. It was restored as provincial capital in the 1920s. In 2002 it became a university city.

The citizens of the city have a high incidence of multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease seen more frequently among people of North European extraction; perhaps this is related to the Norman immigration. MS is also prevalent in Sardinia, which has the second highest incidence in the Mediterranean basin.[6]

Classical mythology

The neighborhood of Enna is celebrated in myth as the place whence Persephone (Latin: Proserpine) was carried off by Pluto, god of the underworld.[7] The spot assigned by local tradition as the scene of this event was a small lake surrounded by lofty and precipitous hills, about 8 km from Enna. The meadows abound in flowers, and a nearby cavern or grotto was believed to be where the king suddenly emerged. This lake is called "Pergus" by Ovid [8] and Claudian.[9] Neither Cicero nor Diodorus refers to any lake in relation to this myth. The former says that around Enna were lacus lucique plurimi, et laetissimi flores omni tempore anni.[10] Diodorus describes the spot whence Persephone was carried off as a meadow so full of fragrant flowers that hounds could not follow their prey. He described the meadow as enclosed on all sides by steep cliffs, and having groves and marshes in the neighborhood, but does not refer to a lake.[11] Both he and Cicero allude to a cavern, as if describing a definite site. In the 21st century, a small lake is found in a basin-shaped hollow surrounded by great hills, and a cavern near is noted as that described by Cicero and Diodorus. But much of the flowers and trees had disappeared by the 19th century, when travelers described the area as bare and desolate.[12]

Both Ceres and Persephone were worshipped in Enna. Cicero said that the temple of Ceres was of such great antiquity and sanctity that Sicilians went there filled with religious awe. Verres looted from it a bronze image of the deity, the most ancient as well as the most venerated in Sicily.[13] No remains of this temple are now visible. Standing on the brink of the brink of the precipice, it fell with a great rockfall from the edge of the cliff.[14] Other remnants of classical antiquity were likely destroyed by the Saracens, who erected the castle and several other of the most prominent buildings of the modern city.[15]

Ancient name Henna

Coins minted for Enna under the Roman dominion still exist, carrying the legend "MUN. (Municipium) HENNA". The aspirated form of the name confirms the authority of Cicero, whose manuscripts give that form.[16] The most ancient Greek coin of the city also gives the name "ΗΕΝΝΑΙΟΝ".[17] Scholars have concluded that this form, Henna, of the ancient name is the more correct for its time, though Enna is the more usual.

University, culture and education

Enna is now an important center for archaeological and educational studies. The Kore University of Enna was officially founded in 2002.

Main sights

The most important monuments of Enna are:

- The Castello di Lombardìa (Lombardy Castle), perhaps the most important example of military architecture in Sicily. It was built by Sicanians, rebuilt by Frederick II of Sicily, and restructured under Frederick II of Aragon. The castle is named for the garrison of Lombard troops that defended it in Norman times. It has an irregular layout which once comprised 20 towers: of the six remaining, the Torre Pisana is the best preserved. It has Guelph merlons. The castle was divided into three different spaces separated by walls. The first courtyard is the site of a renowned outdoor lyric theater; the second one houses a large green park, while the third courtyard includes the vestiges of royal apartments, a bishop's chapel, medieval prisons, and the Pisan Tower.

- The Duomo (Cathedral), a notable example of religious architecture in Sicily, was built in the 14th century by queen Eleonora, Frederick III's wife. It was renovated and remodeled after the fire of 1446. The great Baroque facade, in yellow tufa-stone, is surmounted by a massive campanile with finely shaped decorative elements. The portal on the right side is from the 16th century, while the other is from the original 14th-century edifice. The interior has a nave with two aisles, separated by massive Corinthian columns, and three apses. The stucco decoration is from the 16th and 17th centuries. Art works include a 15th-century crucifix panel painting, a canvas by Guglielmo Borremans, the presbytery paintings by Filippo Paladini (1613), and a Baroque side portal. The cathedral's treasure is housed in the Alessi Museum, and includes precious ornaments, the gold crown with diamonds known as the "Crown of the Virgin," Byzantine icons, thousands of ancient coins, and other collections.

- Palazzo Varisano was adapted to house the Regional Archaeological Museum of Enna. It has material dating from the Copper Age to the 6th century AD, recovered from many archaeological areas in the Province of Enna.

- Torre di Federico, is an octagonal ancient tower that was allegedly a summer residence of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. The two floors possess beautiful vaults. The aspect of the building is austere. It was part of a bigger complex, named Old castle and destroyed by Arabs. Remnants include some pieces of the old, imposing walls on the top of the green hill where the Tower rises.

.jpg)

- The Campanile of the destroyed church of San Giovanni, features pointed arches with finely shaped archivolts, and a three-light mullioned window with Catalan-style decorations.

- The Municipal Library is located in the San Francesco building, a former church. It has a notable 15th-century campanile and, in the interior, a fine painted Cross from the same century.

- The church of San Tommaso is of note for its 15th-century belfry, with three orders. It has windows framed by an agile full-centered archivolt. The church contains a marble icon (1515) attributed to Giuliano Mancino and precious frescoes by Borremans.

- The Janniscuru Gate is the only one preserved of the seven gates that once gave entrance through the town wall. It is a fine 17th-century Roman arch, positioned in an area of rock grottoes under the ancient, traditional quarter of Fundrisi. These grottoes were used as a necropolis by ancient peoples thousands of years ago.

Pergusa lake and archaeologic site

Lake Pergusa (Latin: Pergus lacus or Hennaeus lacus) lies between a group of mountains in the chain of Erei, about 5 km from Enna. It is part of an important migratory flyway for many species of birds. The Pergusa nature reserve also has numerous species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates.

Around the lake is the most important racing track of Southern Italy, the Autodromo di Pergusa. It has hosted international competitions and events, such as Formula One, Formula 3000, and a Ferrari Festival featuring Michael Schumacher.

Near Pergusa lake is the archaeological site known as Cozzo Matrice. These are the remains of an ancient prehistoric fortified village, with walls dating about 8000 BC. Other remains, dating to more than 2000 years ago, are a sacred citadel, a rich necropolis, and the remains of an ancient temple dedicated to Demeter. Pergusa is strongly linked to the myth of the Greek Persephone, Demeter's daughter, who was kidnapped from here by Pluto and taken to Hades, the underworld, for part of the year. From that captivity, seasons arose.

The important forest and green area named Selva Pergusina (meaning Pergusa's Wood) surrounds a part of the Lake Pergusa Valley.

Climate

The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Csa" (Mediterranean Climate).[18]

| Climate data for Enna (1971–2000, extremes 1946–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.0 (98.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

37.4 (99.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

0.6 (33.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70.4 (2.77) |

56.9 (2.24) |

46.9 (1.85) |

43.2 (1.70) |

22.9 (0.90) |

17.7 (0.70) |

8.2 (0.32) |

25.3 (1.00) |

40.6 (1.60) |

79.3 (3.12) |

73.6 (2.90) |

71.0 (2.80) |

556.0 (21.89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.9 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 3.5 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 64.2 |

| Source: Servizio Meteorologico[19][20] | |||||||||||||

Government

Sister cities

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Popolazione Residente al 1° Gennaio 2018". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Barbette S. Spaeth, The Roman Goddess Ceres, pp. 73-74, 78-79, 129 (U. of Texas Press 1996) ISBN 0-292-77693-4.

- Paul Fregosi (1998) Jihad in the West: Muslim Conquests from the 7th to the 21st Centuries, pp. 132-133.

- http://www.ilcampanileenna.it/i-normanni.html

- Ovid, Met. v. 385-408; Claudian, de Rapt. Proserp. ii.; Diod. v. 3.

- Met. v. 386.

- l. c. ii. 112.

- Cicero, In Verrem iv. 48.

- v. 3.

- Richard Hoare (1819) Classical Tour. London: J. Mawman, vol. ii, p. 252; Gustav Parthey (1834) Wanderungen durch Sicilien und die Levante. Berlin: Nicolaische Buchhandlung, Tl. 1, p. 135; Marquis of Ormonde (1850) Autumn in Sicily. Dublin: Hodges and Smith, p. 106, who has given a view of the lake.

- Cicero In Verrem iv. 4. 8.

- Fazello, Tommaso x. 2. p. 444; M. of Ormonde, p. 92.

- Hoare, l. c. p. 249.

- Zumpt, ad Verr. p. 392.

- Eckhel, vol. i. p. 206.

- Climate Summary for Enna, Italy

- "Enna (EN)" (PDF). Atlante climatico. Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- "Enna: Record mensili dal 1946" (in Italian). Servizio Meteorologico dell’Aeronautica Militare. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Enna. |

- (in Italian) Enna official website

- (in Italian) "InfoEnna": news about Enna and province

- (in Italian) APT: Tourist Agency of Enna

- (in Italian) Enna: tourism, archaeology and nature

- (in Italian) Province of Enna official website