Greek underworld

In mythology, the Greek underworld is an otherworld where souls go after death. The original Greek idea of afterlife is that, at the moment of death, the soul is separated from the corpse, taking on the shape of the former person, and is transported to the entrance of the underworld. Good people and bad people would then separate.[1] The underworld itself—sometimes known as Hades, after its patron god—is described as being either at the outer bounds of the ocean or beneath the depths or ends of the earth.[2] It is considered the dark counterpart to the brightness of Mount Olympus with the kingdom of the dead corresponding to the kingdom of the gods.[3] Hades is a realm invisible to the living, made solely for the dead.[4]

| Greek underworld |

|---|

| Residents |

| Geography |

| Famous Tartarus inmates |

| Visitors |

Geography

Rivers

There are six main rivers that are visible both in the living world and the underworld. Their names were meant to reflect the emotions associated with death.[5]

- The Styx is generally considered to be one of the most prominent and central rivers of the underworld and is also the most widely known out of all the rivers. It's known as the river of hatred and is named after the goddess Styx. This river circles the underworld seven times.[6]

- The Acheron is the river of pain. It's the one that Charon, also known as the Ferryman, rows the dead over according to many mythological accounts, though sometimes it is the river Styx or both.[7]

- The Lethe is the river of forgetfulness. It is associated with the goddess Lethe, the goddess of forgetfulness and oblivion. In later accounts, a poplar branch dripping with water of the Lethe became the symbol of Hypnos, the god of sleep.[8]

- The Phlegethon is the river of fire. According to Plato, this river leads to the depths of Tartarus.

- The Cocytus is the river of wailing.

- Oceanus is the river that encircles the world,[9] and it marks the east edge of the underworld,[10] as Erebos is west of the mortal world.

Entrance of the underworld

In front of the entrance to the underworld live Grief (Penthos), Anxiety (Curae), Diseases (Nosoi), and Old Age (Geras). Fear (Phobos), Hunger (Limos), Need (Aporia), Death (Thanatos), Agony (Algea), and Sleep (Hypnos), together with Guilty Joys (Gaudia). On the opposite threshold is War (Polemos), the Erinyes, and Discord (Eris). Close to the doors are many beasts, including Centaurs, Scylla, Briareus, Gorgons, the Lernaean Hydra, Geryon, the Chimera, and Harpies. In the midst of all this, an Elm can be seen where false Dreams (Oneiroi) cling under every leaf.[11]

The souls that enter the underworld carry a coin under their tongue to pay Charon to take them across the river. Charon may make exceptions or allowances for those visitors carrying a Golden Bough. Charon is said to be appallingly filthy, with eyes like jets of fire, a bush of unkempt beard upon his chin, and a dirty cloak hanging from his shoulders. Although Charon ferries across most souls, he turns away a few. These are the unburied which can't be taken across from bank to bank until they receive a proper burial.

Across the river, guarding the gates of the underworld is Cerberus. Beyond Cerberus is where the Judges of the underworld decide where to send the souls of the dead — to the Isles of the Blessed (Elysium), or otherwise to Tartarus.[12]

Tartarus

While Tartarus is not considered to be directly a part of the underworld, it is described as being as far beneath the underworld as the earth is beneath the sky.[13] It is so dark that the "night is poured around it in three rows like a collar round the neck, while above it grows the roots of the earth and of the unharvested sea."[14] Zeus cast the Titans along with his father Cronus into Tartarus after defeating them.[15] Homer wrote that Cronus then became the king of Tartarus.[16] While Odysseus does not see the Titans himself, he mentions some of the people within the underworld who are experiencing punishment for their sins.

Asphodel Meadows

The Asphodel Meadows were a place for ordinary or indifferent souls who did not commit any significant crimes, but who also did not achieve any greatness or recognition that would warrant them being admitted to the Elysian Fields. It was where mortals who did not belong anywhere else in the underworld were sent.[17]

Mourning Fields

In the Aeneid, the Mourning Fields (Lugentes Campi) was a section of the underworld reserved for souls who wasted their lives on unrequited love. Those mentioned as residents of this place are Dido, Phaedra, Procris, Eriphyle, Pasiphaë, Evadne, Laodamia, and Caeneus.[18][19]

Elysium

Elysium was a place for the especially distinguished. It was ruled over by Rhadamanthus, and the souls that dwelled there had an easy afterlife and had no labors.[20] Usually, those who had proximity to the gods were granted admission, rather than those who were especially righteous or had ethical merit, however, later on, those who were pure and righteous were considered to reside in Elysium. Most accepted to Elysium were demigods or heroes.[13] Heroes such as Cadmus, Peleus, and Achilles also were transported here after their deaths. Normal people who lived righteous and virtuous lives could also gain entrance such as Socrates who proved his worth sufficiently through philosophy.[13]

Isles of the Blessed

The Fortunate Isles or Isles of the Blessed were islands in the realm of Elysium. When a soul achieved Elysium, they had a choice to either stay in Elysium or to be reborn. If a soul was reborn three times and achieved Elysium all three times, then they were sent to the Isles of the Blessed to live in eternal paradise. As the Elysian Fields expanded to include ordinary people who lived pure lives, the fortunate isles then began to be considered the final destination for demigods and heroes.

Deities

Hades

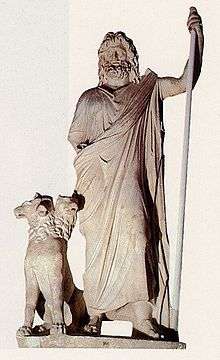

Hades (Aides, Aidoneus, or Haidês), the eldest son of the Titans Cronus and Rhea; brother of Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, and Hestia, is the Greek god of the underworld.[21] When the three brothers divided the world between themselves, Zeus received the heavens, Poseidon the sea, and Hades the underworld; the earth itself was divided between the three. Therefore, while Hades' responsibility was in the underworld, he was allowed to have power on earth as well.[22] However, Hades himself is rarely seen outside his domain, and to those on earth his intentions and personality are a mystery.[23] In art and literature Hades is depicted as stern and dignified, but not as a fierce torturer or devil-like.[22] However, Hades was considered the enemy to all life and was hated by both the gods and men; sacrifices and prayers did not appease him so mortals rarely tried.[24] He was also not a tormenter of the dead, and sometimes considered the "Zeus of the dead" because he was hospitable to them.[25] Due to his role as lord of the underworld and ruler of the dead, he was also known as Zeus Khthonios ("the infernal Zeus" or "Zeus of the lower world"). Those who received punishment in Tartarus were assigned by the other gods seeking vengeance. In Greek society, many viewed Hades as the least liked god and many gods even had an aversion towards him, and when people would sacrifice to Hades, it would be if they wanted revenge on an enemy or something terrible to happen to them.[26]

Hades was sometimes referred to as Pluto and was represented in a lighter way – here, he was considered the giver of wealth, since the crops and the blessing of the harvest come from below the earth.[27]

Persephone

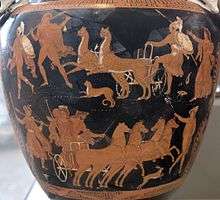

Persephone (also known as Kore) was the daughter of Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, and Zeus. Persephone was abducted by Hades, who desired a wife. When Persephone was gathering flowers, she was entranced by a narcissus flower planted by Gaia (to lure her to the underworld as a favor to Hades), and when she picked it the earth suddenly opened up.[28] Hades, appearing in a golden chariot, seduced and carried Persephone into the underworld. When Demeter found out that Zeus had given Hades permission to abduct Persephone and take her as a wife, Demeter became enraged at Zeus and stopped growing harvests for the earth. To soothe her, Zeus sent Hermes to the underworld to return Persephone to her mother. However, she had eaten six pomegranate seeds in the underworld and was thus eternally tied to the underworld, since the pomegranate seed was sacred there.[29]

Persephone could then only leave the underworld when the earth was blooming, or every season except the winter. The Homeric Hymns describes the abduction of Persephone by Hades:

I sing now of the great Demeter

Of the beautiful hair,

And of her daughter Persephone

Of the lovely feet,

Whom Zeus let Hades tear away

From her mother's harvests

And friends and flowers—

Especially the Narcissus,

Grown by Gaia to entice the girl

As a favor to Hades, the gloomy one.

This was the flower that

Left all amazed,

Whose hundred buds made

The sky itself smile.

When the maiden reached out

To pluck such beauty,

The earth opened up

And out burst Hades ...

The son of Kronos,

Who took her by force

On his chariot of gold,

To the place where so many

Long not to go.

Persephone screamed,

She called to her father,

All-powerful and high, ...

But Zeus had allowed this.

He sat in a temple

Hearing nothing at all,

Receiving the sacrifices of

Supplicating men.[30]

Persephone herself is considered a fitting other half to Hades because of the meaning of her name which bears the Greek root for "killing" and the -phone in her name means "putting to death".[22] This is likely a folk-etymology, though, with the original form of her name being "Persophatta", meaning "Goddess of the Threshing Floor" according to Beekes.

Hecate

Hecate was variously associated with crossroads, entrance-ways, dogs, light, the Moon, magic, witchcraft, knowledge of herbs and poisonous plants, necromancy, and sorcery.[31][32]

The Erinyes

The Erinyes (also known as the Furies) were the three goddesses associated with the souls of the dead and the avenged crimes against the natural order of the world. They consist of Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone.

They were particularly concerned with crimes done by children against their parents such as matricide, patricide, and unfilial conduct. They would inflict madness upon the living murderer, or if a nation was harboring such a criminal, the Erinyes would cause starvation and disease to the nation.[33] The Erinyes were dreaded by the living since they embodied the vengeance of the person who was wronged against the wrongdoer.[34] Often the Greeks made "soothing libations" to the Erinyes to appease them so as to not invoke their wrath, and overall the Erinyes received many more libations and sacrifices than other gods of the underworld.[35] The Erinyes were depicted as ugly and winged women with their bodies intertwined with serpents.[36]

Hermes

While Hermes did not primarily reside in the underworld and is not usually associated with the underworld, he was the one who led the souls of the dead to the underworld. In this sense, he was known as Hermes Psychopompos and with his fair golden wand he was able to lead the dead to their new home. He was also called upon by the dying to assist in their passing – some called upon him to have painless deaths or be able to die when and where they believed they were meant to die.[37]

Judges of the underworld

Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Aeacus are the judges of the dead. They judged the deeds of the deceased and created the laws that governed the underworld. However, none of the laws provided a true justice to the souls of the dead, and the dead did not receive rewards for following them or punishment for wicked actions.[38]

Aeacus was the guardian of the Keys of the underworld and the judge of the men of Europe. Rhadamanthus was Lord of Elysium and judge of the men of Asia. Minos was the judge of the final vote.

Charon

Charon is the ferryman who, after receiving a soul from Hermes, would guide them across the rivers Styx and/or Acheron to the underworld. At funerals, the deceased traditionally had an obol placed over their eye or under their tongue, so they could pay Charon to take them across. If not, they were said to fly at the shores for one hundred years, until they were allowed to cross the river.[39] To the Etruscans, Charon was considered a fearsome being – he wielded a hammer and was hook-nosed, bearded, and had animalistic ears with teeth.[13] In other early Greek depictions, Charon was considered merely an ugly bearded man with a conical hat and tunic.[40] Later on, in more modern Greek folklore, he was considered more angelic, like the Archangel Michael. Nevertheless, Charon was considered a terrifying being since his duty was to bring these souls to the underworld and no one would persuade him to do otherwise.

Cerberus

Cerberus (Kerberos), or the "Hell-Hound", is Hades' massive multi-headed (usually three-headed)[41][42][43] dog with some descriptions stating that it also has a snake-headed tail and snake heads on its back and as its mane. Born from Echidna and Typhon, Cerberus guards the gate that serves as the entrance of the underworld.[22] Cerberus' duty is to prevent dead people from leaving the underworld.

Heracles once borrowed Cerberus as the final part of the Labours of Heracles. Orpheus once soothed it to sleep with his music.

According to the Suda, the ancient Greeks placed a honeycake (μελιτοῦττα) with the dead in order (for the dead) to give it to Cerberus.[44]

Thanatos

Thanatos is the personification of death. Specifically, he represented non-violent death as contrasted with his sisters the Keres, the spirits of diseases and slaughter.

Melinoë

Melinoe is a chthonic nymph, daughter of Persephone, invoked in one of the Orphic Hymns and propitiated as a bringer of nightmares and madness.[45] She may also be the figure named in a few inscriptions from Anatolia,[46] and she appears on a bronze tablet in association with Persephone.[47] The hymns, of uncertain date but probably composed in the 2nd or 3rd century AD, are liturgical texts for the mystery religion known as Orphism. In the hymn, Melinoë has characteristics that seem similar to Hecate and the Erinyes,[48] and the name is sometimes thought to be an epithet of Hecate.[49] The terms in which Melinoë is described are typical of moon goddesses in Greek poetry.

Nyx

Nyx is the goddess of the Night.

Tartarus

A deep abyss used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans,[50] Tartarus was also considered to be a primordial deity.

Achlys

Achlys is the personification of misery and sadness, sometimes represented as a daughter of Nyx.

Styx

Styx is the goddess of the river with the same name. Not much is known about her, but she is an ally of Zeus and lives in the underworld.

The dead

In the Greek underworld, the souls of the dead still existed, but they are insubstantial, and flitted around the underworld with no sense of purpose.[51] The dead within the Homeric underworld lack menos, or strength, and therefore they cannot influence those on earth. They also lack phrenes, or wit, and are heedless of what goes on around them and on the earth above them.[52] Their lives in the underworld were very neutral, so all social statuses and political positions were eliminated and no one was able to use their previous lives to their advantage in the underworld.[38]

The idea of progress did not exist in the Greek underworld – at the moment of death, the psyche was frozen, in experience and appearance. The souls in the underworld did not age or really change in any sense. They did not lead any sort of active life in the underworld – they were exactly the same as they were in life.[53] Therefore, those who had died in battle were eternally blood-spattered in the underworld and those who had died peacefully were able to remain that way.[54]

Overall, the Greek dead were considered to be irritable and unpleasant, but not dangerous or malevolent. They grew angry if they felt a hostile presence near their graves and drink offerings were given in order to appease them so as not to anger the dead.[55] Mostly, blood offerings were given, due to the fact that they needed the essence of life to become communicative and conscious again.[38] This is shown in Homer's Odyssey, where Odysseus had to give blood in order for the souls to interact with him. While in the underworld, the dead passed the time through simple pastimes such as playing games, as shown from objects found in tombs such as dice and game-boards.[56] Grave gifts such as clothing, jewelry, and food were left by the living for use in the underworld as well, since many viewed these gifts to carry over into the underworld.[53] There was not a general consensus as to whether the dead were able to consume food or not. Homer depicted the dead as unable to eat or drink unless they had been summoned; however, some reliefs portray the underworld as having many elaborate feasts.[56] While not completely clear, it is implied that the dead could still have sexual intimacy with another, although no children were produced. The Greeks also showed belief in the possibility of marriage in the underworld, which in a sense describes the Greek underworld having no difference than from their current life.[57]

Lucian described the people of the underworld as simple skeletons. They are indistinguishable from each other, and it is impossible to tell who was wealthy or important in the living world.[58] However, this view of the underworld was not universal – Homer depicts the dead keeping their familiar faces.

Hades itself was free from the concept of time. The dead are aware of both the past and the future, and in poems describing Greek heroes, the dead helped move the plot of the story by prophesying and telling truths unknown to the hero.[53] The only way for humans to communicate with the dead was to suspend time and their normal life to reach Hades, the place beyond immediate perception and human time.[53]

Greek attitudes

The Greeks had a definite belief that there was a journey to the afterlife or another world. They believed that death was not a complete end to life or human existence.[59] The Greeks accepted the existence of the soul after death, but saw this afterlife as meaningless.[60] In the underworld, the identity of a dead person still existed, but it had no strength or true influence. Rather, the continuation of the existence of the soul in the underworld was considered a remembrance of the fact that the dead person had existed, yet while the soul still existed, it was inactive.[61] However, the price of death was considered a great one. Homer believed that the best possible existence for humans was to never be born at all, or die soon after birth, because the greatness of life could never balance the price of death.[62] The Greek gods only rewarded heroes who were still living; heroes that died were ignored in the afterlife. However, it was considered very important to the Greeks to honor the dead and was seen as a type of piety. Those who did not respect the dead opened themselves to the punishment of the gods – for example, Odysseus ensured Ajax's burial, or the gods would be angered.[63]

Myths and stories

Orpheus

Orpheus, a poet and musician that had almost supernatural abilities to move anyone to his music, descended to the underworld as a living mortal to retrieve his dead wife Eurydice after she was bitten by a poisonous snake on their wedding day. With his lyre-playing skills, he was able to put a spell on the guardians of the underworld and move them with his music.[64] With his beautiful voice he was able to convince Hades and Persephone to allow him and his wife to return to the living. The rulers of the underworld agreed, but under one condition – Eurydice would have to follow behind Orpheus and he could not turn around to look at her. Once Orpheus reached the entrance, he turned around, longing to look at his beautiful wife, only to watch as his wife faded back into the underworld. He was forbidden to return to the underworld a second time and he spent his life playing his music to the birds and the mountains.[65]

See also

- Hades in Christianity

References

- Long, J. Bruce (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 9452.

- Garland, Robert (1985). The Greek Way of Death. London: Duckworth. p. 49.

- Fairbanks, Arthur (1 January 1900). "The Chthonic Gods of Greek Religion". The American Journal of Philology. 21 (3): 242. doi:10.2307/287716. JSTOR 287716.

- Albinus, Lars (2000). The House of Hades: studies in ancient Greek eschatology. Aarhus University Press: Aarhus. p. 67.

- Mirto, Maria Serena; A. M Osborne (2012). Death in the Greek World: From Homer to the Classical Age. Normal: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 16.

- Leeming, David (2005). "Styx". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195156690.001.0001. ISBN 9780195156690. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Buxton, R.G.A (2004). The Complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 209.

- "Theoi Project: Lethe". Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- The Iliad

- The Odyssey

- Virgil, Aeneid 268 ff

- "Underworld and Afterlife - Greek Mythology Link". Maicar.com. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- Buxton pg.213

- Garland pg.51

- Garland pg.50

- Albinus pg.87

- "The Greek Underworld". Wiki.uiowa.edu. 2010-01-31. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- Wordsworth, William. Knight, William (edit.). The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, Volume 6. MacMillan & Co. 1896; pg. 14.

- Virgil. Fairclough, H. Rushton (trans.). Virgil: Eclogues. Georgics. Aeneid I-VI. Vol. 1. William Heinemann. G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1916.

- Albinus pg.86

- "Theoi Project: Haides". Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- O'Cleirigh, Padraig (2000). An Introduction to Greek mythology : story, symbols, and culture. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. p. 190.

- Mirto pg.21

- Peck, Harry Thurston (1897). Harper's Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities. Harper. p. 761.

- Garland pg.52

- "Hades". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2012-12-05.

- Peck pg.761

- Leeming, David (2005). "Demeter and Persephone". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195156690.001.0001. ISBN 9780195156690. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Pfister, F (1961). Greek Gods and Heroes. London: Macgibbon & Kee. p. 86.

- Leeming, Demeter and Persephone

- "HECATE : Greek goddess of witchcraft, ghosts & magic; mythology; pictures : HEKATE". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- d'Este, Sorita & Rankine, David, Hekate Liminal Rites, Avalonia, 2009.

- "Theoi Project: Erinyes". Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- Fairbanks pg.251

- Fairbanks pg.255

- Theoi Project: Erinyes

- Garland pgs.54-55

- Long pg.9453

- Virgil, Aeneid 6, 324–330.

- "Theoi Project: Kharon". Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- "Cerberus". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- "Yahoo! Deducation". Archived from the original on 2012-10-21.

- Cerberus definition - Dictionary - MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31.

- Suda μ 526.

- Orphic Hymn 70 or 71 (numbering varies), as given by Richard Wünsch, Antikes Zaubergerät aus Pergamon (Berlin, 1905), p. 26:

Μηλινόην καλέω, νύμφην χθονίαν, κροκόπεπλον,

ἣν παρὰ Κωκυτοῦ προχοαῖς ἐλοχεύσατο σεμνὴ

Φερσεφόνη λέκτροις ἱεροῖς Ζηνὸς Κρονίοιο

ᾗ ψευσθεὶς Πλούτων᾽ἐμίγη δολίαις ἀπάταισι,

θυμῷ Φερσεφόνης δὲ διδώματον ἔσπασε χροιήν,

ἣ θνητοὺς μαίνει φαντάσμασιν ἠερίοισιν,

ἀλλοκότοις ἰδέαις μορφῆς τὐπον έκκπροφανοῦσα,

ἀλλοτε μὲν προφανής, ποτὲ δὲ σκοτόεσσα, νυχαυγής,

ἀνταίαις ἐφόδοισι κατὰ ζοφοειδέα νύκτα.

ἀλλἀ, θεά, λίτομαί σε, καταχθονίων Βασίλεια,

ψυχῆς ἐκπέμπειν οἶστρον ἐπὶ τέρματα γαίης,

εὐμενὲς εὐίερον μύσταις φαίνουσα πρόσωπον. - Jennifer Lynn Larson, Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore (Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 268.

- Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, "Orphic Mythology," in A Companion to Greek Mythology (Blackwell, 2011), note 58, p. 100; Apostolos N. Athanassakis, The Orphic Hymns: Text, Translation, and Notes (Scholars Press, 1977), p. viii.

- Edmonds, "Orphic Mythology," pp. 84–85.

- Ivana Petrovic, Von den Toren des Hades zu den Hallen des Olymp (Brill, 2007), p. 94; W. Schmid and O. Stählin, Geschichte der griechischen Literatur (C.H. Beck, 1924, 1981), vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 982; W.H. Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie (Leipzig: Teubner, 1890–94), vol. 2, pt. 2, p. 16.

- Georg Autenrieth. "Τάρταρος". A Homeric Dictionary. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- Mikalson, Jon D (2010). Ancient Greek Religion. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 177.

- Garland pg.1

- Albinus pg.27

- Garland pg.74

- Garland pgs.5-6

- Garland pg.70

- Garland pg.71

- O’Cleirigh pg.191

- Mystakidou, Kyriaki; Eleni Tsilika; Efi Parpa; Emmanuel Katsouda; Lambros Vlahos (1 December 2004). "Death and Grief in the Greek Culture". OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying. 50 (1): 24. doi:10.2190/YYAU-R4MN-AKKM-T496. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Mikalson pg.178

- Mystakidou pg.25

- Mystakidou pg.24

- Garland pg.8

- Albinus pg.105

- Hamilton, Edith. "The Story of Orpheus and Eurydice". Retrieved December 2, 2012.

Bibliography

- Albinus, Lars (2000). The House of Hades: Studies in Ancient Greek Eschatology. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Buxton, R (2004). The complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Camus, Albert. "The Myth of Sisyphus". Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Fairbanks, Arthur (1900). "The Chthonic Gods of Greek Religion". The American Journal of Philology. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 21 (3): 241–259. doi:10.2307/287716. JSTOR 287716.

- Garland, Robert (1985). The Greek Way of Death. London: Duckworth.

- Leeming, David (2005). "Demeter and Persephone". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195156690.001.0001. ISBN 9780195156690. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Leeming, David (2005). "Styx". The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195156690.001.0001. ISBN 9780195156690. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Long, J. Bruce (2005). "Underworld". Encyclopedia of Religion. Macmillan Reference USA. 14: 9451–9458.

- Mirtro, Marina Serena (2012). Death in the Greek world : from Homer to the classical age. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Mikalson, Jon D (2010). Ancient Greek Religion. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Mystakidou, Kyriaki; Tsilika, Eleni; Parpa, Efi; Katsouda, Elena; Vlahous, Lambros (2004–2005). "Death and Grief in the Greek Culture". Omega. Baywood Publishing Co. 50 (1): 23–34. doi:10.2190/yyau-r4mn-akkm-t496.

- O’Cleirigh, Padraig, Rex A Barrell, and John M Bell (2000). An introduction to Greek mythology : story, symbols, and culture. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Peck, Harry Thurston (1897). Harper's Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities. Harper.

- Pfister, F (1961). Greek Gods and Heroes. London: Macgibbon & Kee.

- Scarfuto, Christine. "The Greek Underworld". Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Schmiel, Robert (1987). "Achilles in Hades". Classical Philology. The University of Chicago Press. 82 (1): 35–37. doi:10.1086/367020. JSTOR 270025.