Phaistos

Phaistos (Greek: Φαιστός, pronounced [feˈstos]; Ancient Greek: Φαιστός, pronounced [pʰai̯stós], Minoan: PA-I-TO?[5]), also transliterated as Phaestos, Festos and Latin Phaestus, is a Bronze Age archaeological site at modern Faistos, a municipality in south central Crete. Ancient Phaistos was located about 5.6 km (3.5 mi) east of the Mediterranean Sea and 62 km (39 mi) south of Heraklio, the second largest city of Minoan Crete.[6] The name Phaistos survives from ancient Greek references to a city in Crete of that name at or near the current ruins.

.jpg) View of Phaistos | |

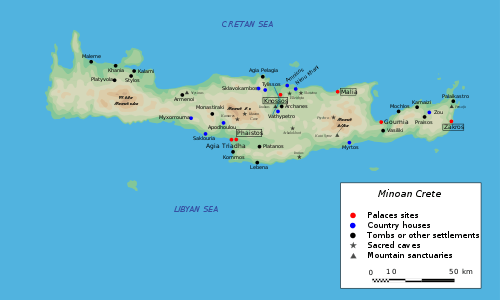

Map of Minoan Crete | |

| Alternative name | Phaestus |

|---|---|

| Location | Faistos, Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

| Region | The eastern point of a ridge overlooking Messara Plain to the east |

| Coordinates | 35°03′05″N 24°48′49″E |

| Type | Palace complex and city |

| Part of | The state ruled from Knosses under a monarchy symbolized by "King Minos" |

| Area | 8,400 m2 (90,000 sq ft)[2] for the palace. The city covered the hill and a few km into the valley below. |

| History | |

| Builder | Unknown |

| Material | Trimmed blocks of limestone and alabaster, mud-brick, rubble, wood |

| Founded | The first settlement dates to the Late Neolithic starting about 3000 BC. The first palace dates to about 1850 BC.[3] New palace dates to around 1700 BC[4] |

| Periods | Late Neolithic to Late Bronze Age. The first palace was built at the start of Middle Minoan |

| Cultures | Minoan |

| Satellite of | The kingdom centered at Knossos |

| Associated with | In the Bronze Age, people of unknown ethnicity now called Minoans |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1874, Federico Halbherr alone 1900–1904, 1950–1971, Italian School of Archaeology at Athens Since 2007, the Phaistos Project |

| Archaeologists | 1900–1904, Federico Halbherr and Luigi Pernier 1950–1972, Doro Levi |

| Condition | Current interventions are tamped soil, stone walkways, hand rails, lightly roofed areas, with more planned.[2] |

| Management | 23rd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquitites; Italian School of Archaeology at Athens; University of Salerno, Department of Cultural Heritage Sciences |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | "Phaistos". |

The name is substantiated by the coins of the classical city. They display motifs such as Europa sitting on a bull, Talos with wings, Heracles without beard and being crowned, and Zeus in the form of a naked youth sitting on a tree. On either the obverse or the reverse the name of the city, or its abbreviation, is inscribed, such as ΦΑΙΣ or ΦΑΙΣΤΙ, for Phaistos or Phaistios ("Phaistian" adjective) written either right-to-left or left-to-right.[7] These few dozen coins were acquired by collectors from uncontrolled contexts. They give no information on the location of Phaistos.

Archaeology

Phaistos was located by Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt, commander of the Spitfire, a paddle steamer, in the Mediterranean Survey of 1853, which described the topography, settlements and monuments of Crete.[8] Spratt followed the directions of Strabo, who said:[9]

Of the three cities that were united under one metropolis by Minos, the third, which was Phaestus, was razed to the ground by the Gortynians; it is sixty stadia distant from Gortyn, twenty from the sea, and forty from the seaport Matalum; and the country is held by those who razed it.

The simple geometric problem posed by these distances from known points was solved with no difficulty by the survey. The location pinpointed was the eastern end of a hill, or ridge, rising from the middle of the Geropotamos river valley extending from the sea to the Messara Plain in an east–west direction. The hill was called Kastri ("fort", "small castle"). A military man, Spratt understood the significance of the location immediately:

I thus found that Phaestus had occupied the extremity of a ridge that divides the maritime plain of Debaki from the plain of the Messara, so as to command the narrow valley of communication.[10]

A village of 16 houses remained on the ridge, but the vestiges of fortification walls indicated a city had once existed there. A half-century later, after removing the houses, Federico Halbherr and his crew began to discover the remains of an extensive palace complex. As he had begun excavation before Arthur Evans at Knossos in 1900, he did not have the advantage of Evans' concepts of Minoan civilization nor the knowledge acquired after the decipherment of the Linear B syllabary by Michael Ventris. Excavation ended in 1904, to begin again after another half-century, in 1950. By this time it was understood that the palace had been constructed at the beginning of the Proto-Palace Period. After 1955 the place name, 𐀞𐀂𐀵, pa-i-to, interpreted as Phaistos (written in Mycenaean Greek),[11] began to turn up in the Linear B tablets at Knossos, then under the Mycenaean Greeks. There was every reason to think that pa-i-to was located at Kastri.

No Linear B has been found at Phaistos, but tradition and the Knossos tablets suggest that Phaistos was a dependency of Knossos. Moreover, only a few pieces of Linear A have been found. As Phaistos appears to have been an administrative center, the lack of records is surprising.

In 1908, Pernier found the Phaistos Disc in the basements of the northern group of the palace. This artifact is a clay disk, dated to between 1950 BC and 1400 BC and impressed with a unique, sophisticated hieroglyphic script.

The tombs of the rulers of Phaistos were found in a cemetery 20 minutes away from the palace remains.

Bronze Age

Phaistos was inhabited from about 4000 BC.[12] A palace, dating from the Middle Bronze Age, was destroyed by an earthquake during the Late Bronze Age. Knossos along with other Minoan sites was destroyed at that time. The palace was rebuilt toward the end of the Late Bronze Age.

The first palace was built about 2000 BC. This section is on a lower level than the west courtyard and has a nice facade with a plastic outer shape, a cobbled courtyard, and a tower ledge with a ramp, which leads up to a higher level. The old palace was destroyed three times in period of about three centuries. After the first and second disaster, reconstruction and repairs were made, so there are distinguished three construction phases.

The Old Palace was built in the Protopalatial Period,[13] then rebuilt twice due to extensive earthquake damage. When the palace was destroyed by earthquakes, the re-builders constructed a New Palace atop the old.

Several artifacts with Linear A inscriptions were excavated at this site. The name of the site also appears in partially deciphered Linear A texts, and is probably similar to Mycenaean 'PA-I-TO' as written in Linear B. Several kouloura structures (subsurface pits) have been found at Phaistos. Pottery has been recovered at Phaistos from in the Middle and Late Minoan periods, including polychrome items and embossing in imitation of metal work. Bronze Age works from Phaistos include bridge spouted bowls, eggshell cups, tall jars and large pithoi.[14]

In one of the three hills of the area, remains of the middle neolithic age have been found, and a part of the palace was built during the Early Minoan period. Another two palaces seems to have been built at the Middle and Late Minoan Age. The older looks like the Minoan palace of Knossos, although this is smaller. An earthquake c. 18th century BC destroyed the palace but a larger palace of the later Minoan period was built on the ruins around 1700 BC,[15] consisting of several rooms separated by columns.

The levels of the theater area, in conjunction with two splendid staircases, gave a grand access to the main hall of the propylaea through high doors. A twin gate led directly to the central courtyard through a wide street. The floors and walls of the interior rooms were decorated with plates of sand and white gypsum stone. Upper floors of the west sector had spacious ceremonial rooms, although their exact restoration was not possible.

A brilliant entrance from the central courtyard led to the royal apartments in the north part of the palace, with a view of the tops of Psiloritis. The rooms were constructed from alabaster and other materials. The rooms for princes were smaller and less luxurious than the rooms of the royal departments.

Around 1400 BC, the invading Achaeans destroyed Phaistos, as well as Knossos. The palace appears to have been unused thereafter, as evidence of the Mycenaean era have not been found.

Iron Age

References to Phaistos in ancient Greek literature are quite frequent. Phaistos is first referenced by Homer as "well populated",[16] and the Homeric epics indicate its participation in the Trojan War.[17] The historian Diodorus Siculus indicates[18] that Phaistos, together with Knossos and Kydonia, are the three towns that were founded by King Minos on Crete. Instead, Pausanias and Stephanus of Byzantium supported in their texts that the founder of the city was Phaestos, son of Hercules or Ropalus.[19] The city of Phaistos is associated with the mythical king of Crete Rhadamanthys.

The site was reinhabited during the Geometric Age (8th century BC). Phaistos had its own currency and had created an alliance with other autonomous Cretan cities, and with the king of Pergamon Eumenes II. Around the end of the 3rd century BC, Phaestos was destroyed by the Gortynians and since then ceased to exist in the history of Crete. Scotia Aphrodite and goddess Leto, who was also called Phytia, were worshiped there. The people of Phaistos were distinguished for their funny adages. Epimenides, the wise man invited by the Athenians to clean the city after the Cylonian affair (Cyloneio agos) in the 6th century BC, was of Phaistian descent.

Entryway to the palace

Entryway to the palace Archaeological site of Phaistos

Archaeological site of Phaistos Bird clasping a fish. Decoration of a clay alabastron from Kalyvia, Phaistos, Crete. Early postpalatial period

Bird clasping a fish. Decoration of a clay alabastron from Kalyvia, Phaistos, Crete. Early postpalatial period

(1350–1300 B.C.)

See also

References

- http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/11991/4031&ved=2ahUKEwjor62y3bHoAhUEqYsKHZaZArAQFjASegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw1MwIv3ekgX-SxkJrbORipd

- Stratis, James C. (October 2005), Kommos Archaeological Site Conservation Report (PDF), kommosconservancy.org

- LaRosa, Vincenzo (November–December 1995). "A hypothesis on earthquakes and political power in Minoan Crete" (PDF). Annali di Geofisica. 38 (5–6): 883. The 1850 date was proposed by Doro Levi, who did not agree with Evans on every point.

- "Phaistos Heraklion Crete".

- http://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/download/11991/4031&ved=2ahUKEwjor62y3bHoAhUEqYsKHZaZArAQFjASegQIAhAB&usg=AOvVaw1MwIv3ekgX-SxkJrbORipd

- "The Minoan Palaces, Knossos-Phaistos | Grecotel".

- Wroth, Warwick; Poole, Reginald Stuart (Editor) (1886). Catalogue of the Greek Coins of Crete and the Aegean Islands (PDF). London: British Museum. pp. 61–64.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Spratt, T A B (1865). Travels and Researches in Crete. Volume I. London: John Van Voorst. p. 1.

- Geography Book X, Chapter 4.

- Spratt, T A B (1865). Travels and Researches in Crete. Volume II. London: John Van Voorst. pp. 23–25.

- "The Linear B word pa-i-to". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool for ancient languages.

- "Sights – Phaistos Palace – Hotel Sunshine Matala – ILIAKI in Matala Crete Greece!". matala-holidays.gr.

- Phaistos Palace, Ian Swindale Retrieved 12 May 2013

- C. Michael Hogan, Phaistos Fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian (2007)

- "Orientations of the Minoan palace at Phaistos in Crete".

- Iliad, B 648, Odyssey, C 269

- Homer Iliad Book II. Catalogue of Ships (2.494-759)

- Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca historica

- Pausanias Description of Greece, Book II: Corinth (IV, 7)

Further reading

- Adams, E. (2007). "Approaching Monuments in the Prehistoric Built Environment: New Light on the Minoan Palaces." Oxford Journal Of Archaeology, 26(4), 359–394.

- Borgna, Elisabetta. (2004). "Social Meanings of Food and Drink Consumption at LM III Phaistos." In Food, Cuisine and Society in Prehistoric Greece. Edited by Paul Halstead and John C. Barrett. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 174–195.

- Driessen, Jan, and Florence Gaignerot-Driessen. (2015). Cretan Cities: Formation and Transformation. Aegis, 7. Louvain-La-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain.

- Leitao, David D. (1995). The Perils of Leukippos. Initiatory Transvestism and Male Gender Ideology in the Ekdusia at Phaistos. Classical Antiquity 14:130–163.

- Levi, Doro. (1976–1981). Festòs e la civiltà minoica. 6 vols. Rome: Edizioni dell’Ateneo.

- Myers, J. Wilson, Eleanor Emlen Myers, and Gerald Cadogan, eds. (1992). The Aerial Atlas of Ancient Crete. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press; London: Thames and Hudson.

- Shaw, Joseph W. (2015). Elite Minoan Architecture: Its Development at Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia. Prehistory monographs, 49. Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press.

- Shelmerdine, Cynthia W., ed. (2008). The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Vansteenhuyse, Klaas. (2011). "Centralisation and the Political Institution of Late Minoan IA Crete." In State Formation in Italy and Greece: Questioning the Neoevolutionist Paradigm. Edited by Nicola Terrenato and Donald C. Haggis. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 61–74.

- Watrous, L. Vance, Despoina Hadzi-Vallianou, and Harriet Blitzer. (2004). The Plain of Phaistos: Cycles of Social Complexity in the Mesara Region of Crete. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, Univ. of California.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phaistos. |

| Library resources about Phaistos |

- Swindale, Ian. "Minoan Crete: Bronze Age Civilization: Phaistos page".

- Rutter, Jeremy B. "Aegean Prehistoric Archaeology". Dartmouth College; The Foundation of the Hellenic World. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Architecture of Minoan Crete: constructing identity in the Aegean Bronze Age, John C. McEnroe, University of Texas Press, 2010. 202 pages

- Phaistos Project: Italo-Greek archaeological surveys in the city and territory of Phaistos