Cedrus libani

Cedrus libani, the cedar of Lebanon or Lebanon cedar (Arabic: أرز لبناني), is a species of tree in the pine family Pinaceae, native to the mountains of the Eastern Mediterranean basin. It is a large evergreen conifer that has great religious and historical significance in the cultures of the Middle East, and is referenced many times in the literature of ancient civilisations. It is the national emblem of Lebanon and is widely used as an ornamental tree in parks and gardens.

| Cedrus libani | |

|---|---|

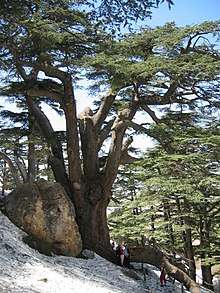

| |

| Cedars of God, (Bsharri) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Cedrus |

| Species: | C. libani |

| Binomial name | |

| Cedrus libani | |

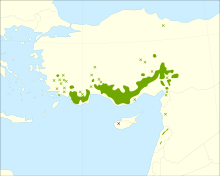

| |

| Distribution map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Several, including:

| |

Description

Cedrus libani can reach 40 m (130 ft) in height, with a massive monopodial columnar trunk up to 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) in diameter.[3] The trunks of old trees ordinarily fork into several large, erect branches.[4] The rough and scaly bark is dark grey to blackish brown, and is run through by deep, horizontal fissures that peel in small chips. The first-order branches are ascending in young trees; they grow to a massive size and take on a horizontal, wide-spreading disposition. Second-order branches are dense and grow in a horizontal plane. The crown is conical when young, becoming broadly tabular with age with fairly level branches; trees growing in dense forests maintain more pyramidal shapes.

Shoots and leaves

The shoots are dimorphic, with both long and short shoots. New shoots are pale brown, older shoots turn grey, grooved and scaly. C. libani has slightly resinous ovoid vegetative buds measuring 2 to 3 mm (0.079 to 0.118 in) long and 1.5 to 2 mm (0.059 to 0.079 in) wide enclosed by pale brown deciduous scales. The leaves are needle-like, arranged in spirals and concentrated at the proximal end of the long shoots, and in clusters of 15–35 on the short shoots; they are 5 to 35 mm (0.20 to 1.38 in) long and 1 to 1.5 mm (0.039 to 0.059 in) wide, rhombic in cross-section, and vary from light green to glaucous green with stomatal bands on all four sides.[3][5]

Cones

Cedrus libani produces cones at around the age of 40; it flowers in autumn, the male cones appear in early September and the female ones in late September.[6][5] Male cones occur at the ends of the short shoots; they are solitary and erect about 4 to 5 cm (1.6 to 2.0 in) long and mature from a pale green to a pale brown color. The female seed cones also grow at the terminal ends of short shoots. The young seed cones are resinous, sessile, and pale green; they require 17 to 18 months after pollination to mature. The mature, woody cones are 8 to 12 cm (3.1 to 4.7 in) long and 3 to 6 cm (1.2 to 2.4 in) wide; they are scaly, resinous, ovoid or barrel-shaped, and gray-brown in color. Mature cones open from top to bottom, they disintegrate and lose their seed scales, releasing the seeds until only the cone rachis remains attached to the branches.[4][5][6][7]

The seed scales are thin, broad, and coriaceous, measuring 3.5 to 4 cm (1.4 to 1.6 in) long and 3 to 3.5 cm (1.2 to 1.4 in) wide. The seeds are ovoid, 10 to 14 mm (0.39 to 0.55 in) long and 4 to 6 mm (0.16 to 0.24 in) wide, attached to a light brown wedge-shaped wing that is 20 to 30 mm (0.79 to 1.18 in) long and 15 to 18 mm (0.59 to 0.71 in) wide.[7] C. libani grows rapidly until the age of 45 to 50 years; growth becomes extremely slow after the age of 70.[6]

Taxonomy

Cedrus is the Latin name for true cedars.[8] The specific epithet refers the Lebanon mountain range where the species was first described by French botanist Achille Richard; the tree is commonly known as the Lebanon cedar or cedar of Lebanon.[3][9] Two distinct types are recognized as varieties: C. libani var. libani and C. libani var. brevifolia.[3]

C. libani var. libani: Lebanon cedar, cedar of Lebanon – grows in Lebanon, western Syria, and south-central Turkey. C. libani var. stenocoma (the Taurus cedar), considered a subspecies in earlier literature, is now recognized as an ecotype of C. libani var. libani. It usually has a spreading crown that does not flatten. This distinct morphology is a habit that is assumed to cope with the competitive environment, since the tree occurs in dense stands mixed with the tall-growing Abies cilicica, or in pure stands of young cedar trees.[7]

C. libani var. brevifolia: The Cyprus cedar occurs on the island's Troodos Mountains.[7] This taxon was considered a separate species from C.libani because of morphological and ecophysiological trait differences.[10][11] It is characterized by slow growth, shorter needles, and higher tolerance to drought and aphids.[11][12] Genetic relationship studies, however, did not recognize C. brevifolia as a separate species, the markers being undistinguishable from those of C. libani.[13][14]

Distribution and habitat

C. libani var. libani is endemic to elevated mountains around the Eastern Mediterranean in Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey. The tree grows in well-drained calcareous lithosols on rocky, north- and west-facing slopes and ridges and thrives in rich loam or a sandy clay in full sun.[3][15] Its natural habitat is characterized by warm, dry summers and cool, moist winters with an annual precipitation of 1,000 to 1,500 mm (39 to 59 in); the trees are blanketed by a heavy snow cover at the higher altitudes.[3] In Lebanon and Turkey, it occurs most abundantly at altitudes of 1,300 to 3,000 m (4,300 to 9,800 ft), where it forms pure forests or mixed forests with Cilician fir (Abies cilicica), European black pine (Pinus nigra), eastern Mediterranean pine (Pinus brutia), and several juniper species. In Turkey, it can occur as low as 500 m (1,600 ft).[16][3]

C. libani var. brevifolia grows in similar conditions on medium to high mountains in Cyprus from altitudes ranging from 900 to 1,525 m (2,953 to 5,003 ft).[16][3]

History and symbolism

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the earliest great works of literature, the Sumerian hero Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu travel to the legendary Cedar Forest to kill its guardian and cut down its trees. While early versions of the story place the forest in Iran, later Babylonian accounts of the story place the Cedar Forest in the Lebanon.[17]

The Lebanon cedar is mentioned several times in the Hebrew bible. Hebrew priests were ordered by Moses to use the bark of the Lebanon cedar in the treatment of leprosy.[18] Solomon also procured cedar timber to build the Temple in Jerusalem.[19] The Hebrew prophet Isaiah used the Lebanon cedar as a metaphor for the pride of the world,[20] with the tree explicitly mentioned in Psalm 92:13 as a symbol of the righteous.

National and regional significance

The Lebanon cedar is the national emblem of Lebanon, and is displayed on the flag of Lebanon and coat of arms of Lebanon. It is also the logo of Middle East Airlines, which is Lebanon's national carrier. Beyond that, it is also the main symbol of Lebanon's "Cedar Revolution" of 2005, the 2019–20 Lebanese protests, also known as Thawra (meaning revolution in Arabic) along with many Lebanese political parties and movements, such as the Lebanese Forces. Finally, Lebanon is sometimes metonymically referred to as the Land of the Cedars.[21][22]

Arkansas, among other states, has a Champion Tree program that records exceptional tree specimens. The Lebanon cedar recognized by the state is located inside Hot Springs National Park and is estimated to be over 100 years old.[23]

Cultivation

The Lebanon cedar is widely planted as an ornamental tree in parks and gardens.[24][25]

When the first cedar of Lebanon was planted in Britain is unknown, but it dates at least to 1664, when it is mentioned in Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber.[26] In Britain, cedars of Lebanon are known for their use in London's Highgate Cemetery.[24]

C. libani has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit[27] (confirmed 2017).[28]

Propagation

In order to germinate Cedrus Libani seeds potting soil is preferred since it is less likely to contain fungal species which may kill the seedling in its early stages. Before sowing it is important to soak the seed at room temperature for a period of 24 hours followed by cold stratification (3 ~ 5 °C) for two to four weeks. Once the seeds have been sown, it is recommended that they be kept at room temperature (~20 °C) and in the vicinity of sunlight. The soil should be kept slightly damp with low frequency watering. Over-watering may cause damping off which will quickly kill the seedlings. Initial growth will be around 3–5 cm the first year and will accelerate subsequent years.[29]

Uses

Cedar wood is very prized for its fine grain, attractive yellow color, and fragrance. It is exceptionally durable and immune to insect ravages. Wood from C. libani has a density of 560 kg/m³; it is used for furniture, construction, and handicrafts. In Turkey, shelterwood cutting and clearcutting techniques are used to harvest timber and promote uniform forest regeneration. Cedar resin (cedria) and cedar essential oil (cedrum) are prized extracts from the timber and cones of the cedar tree.[30][31]

Ecology and conservation

Over the centuries, extensive deforestation has occurred, with only small remnants of the original forests surviving. Deforestation has been particularly severe in Lebanon and on Cyprus; on Cyprus, only small trees up to 25 m (82 ft) tall survive, though Pliny the Elder recorded cedars 40 m (130 ft) tall there.[32] Attempts have been made at various times throughout history to conserve the Lebanon cedars. The first was made by the Roman emperor Hadrian; he created an imperial forest and ordered it marked by inscribed boundary stones, two of which are in the museum of the American University of Beirut.[33]

Extensive reforestation of cedar is carried out in the Mediterranean region. In Turkey, over 50 million young cedars are planted annually, covering an area around 300 square kilometres (74,000 acres).[34][35] Lebanese cedar populations are also expanding through an active program combining replanting and protection of natural regeneration from browsing goats, hunting, forest fires, and woodworms.[35] The Lebanese approach emphasizes natural regeneration by creating proper growing conditions. The Lebanese state has created several reserves, including the Chouf Cedar Reserve, the Jaj Cedar Reserve, the Tannourine Reserve, the Ammouaa and Karm Shbat Reserves in the Akkar district, and the Forest of the Cedars of God near Bsharri.[36][37][38]

Because during the seedling stage, differentiating C. libani from C. atlantica or C. deodara is difficult,[39] the American University of Beirut has developed a DNA-based method of identification to ensure that reforestation efforts in Lebanon are of the cedars of Lebanon and not other types.[40]

Diseases and pests

C. libani is susceptible to a number of soil-borne, foliar, and stem pathogens. The seedlings are prone to fungal attacks. Botrytis cinerea, a necrotrophic fungus known to cause considerable damage to food crops, attacks the cedar needles, causing them to turn yellow and drop. Armillaria mellea (commonly known as honey fungus) is a basidiomycete that fruits in dense clusters at the base of trunks or stumps and attacks the roots of cedars growing in wet soils. The Lebanese cedar shoot moth (Parasyndemis cedricola) is a species of moth of the family Tortricidae found in the forests of Lebanon and Turkey; its larvae feed on young cedar leaves and buds.[30]

See also

- Cedar Forest – Lebanon cedar forest that was home to the gods in Ancient Mesopotamian religion

- Cedars of God – an old-growth C. libani forest and World Heritage Site

- List of plants known as cedar

References

- Gardner, M. (2013). "Cedrus libani". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T46191675A46192926. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T46191675A46192926.en.

- Knight Syn. Conif. 42 1850

- Farjon 2010, p.258

- Masri 1995

- Hemery & Simblet 2014, p.53

- CABI 2013, p. 116

- Farjon 2010, p.259

- Farjon 2010, p.254

- Bory 1823, p.299

- Debazac 1964

- Ladjal 2001

- Fabre et al. 2001, pp. 88–89

- Fady et al. 2000

- Kharrat 2006, p.282

- "Cedrus libani Cedar of Lebanon PFAF Plant Database". pfaf.org. Plants for a Future. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Conifer Specialist Group (1998). "Cedrus libani". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998. Retrieved 12 May 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sherratt, Susan; Bennet, John (2017). Archaeology and Homeric epic. Oxford: Oxbow Books. p. 127. ISBN 9781785702969. OCLC 959610992.

- Leviticus 14:1–4

- "Welcome to Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Church's Homepage". Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Isaiah 2:13

- Erman 1927, p.261

- Cromer 2004, p.58

- "Cedar Lebanon (Cedrus libani)". Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Hemery & Simblet 2014, p.55

- Howard 1955, p.168

- Hemery & Simblet 2014, p. 54.

- "Cedrus libani". www.rhs.org. Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "AGM Plants – Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 16. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Tree Seed Online LTD

- CABI 2013, p. 117

- Coxe 1808, p.CED

- Willan, R. G. N. (1990). The Cyprus Cedar. Int. Dendrol. Soc. Yearbk. 1990: 115–118.

- Shackley, pp. 420–421

- Anon. History of Turkish Forestry. Turkish Ministry of Forestry.

- Khuri, S., & Talhouk, S. N. (1999). Cedar of Lebanon. Pages 108–111 in Farjon, A., & Page, C. N. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan: Conifers. IUCN/SSC Conifer Specialist Group. ISBN 2-8317-0465-0.

- Talhouk & Zurayk 2004, pp.411–414

- Semaan, M. & Haber, R. 2003. In situ conservation on Cedrus libani in Lebanon. Acta Hort. 615: 415–417.

- Cedars of Lebanon Nature Reserve Archived 19 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Barnard, Anne. "Climate Change Is Killing the Cedars of Lebanon". Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- Farjon, Aljos. Conifers: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, International Union of Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 1999, page 110

Bibliography

- CABI (1 January 2013). Praciak, Andrew (ed.). The CABI Encyclopedia of Forest Trees. Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. ISBN 9781780642369.

- Coxe, John Redman (1 January 1808). The Philadelphia Medical Dictionary: Containing a Concise Explanation of All the Terms Used in Medicine, Surgery, Pharmacy, Botany, Natural History, Chymistry, and Materia Medica. Thomas Dobson; Thomas and George Palmer, printers.

- Cromer, Gerald (1 January 2004). A War of Words: Political Violence and Public Debate in Israel. Frank Cass. ISBN 9780714656311.

- Dagher-Kharrat, Magida Bou; Mariette, Stéphanie; Lefèvre, François; Fady, Bruno; March, Ghislaine Grenier-de; Plomion, Christophe; Savouré, Arnould (21 November 2006). "Geographical diversity and genetic relationships among Cedrus species estimated by AFLP". Tree Genetics & Genomes. 3 (3): 275–285. doi:10.1007/s11295-006-0065-x. ISSN 1614-2942.

- Debazac, E. F. (1 January 1964). Manuel des conifères (in French). École nationale des eaux et forêts.

- Eckenwalder, James E. (14 November 2009). Conifers of the World: The Complete Reference. Timber Press. ISBN 9780881929744.

- Erman, Adolf (1 January 1927). The Literature of the Ancient Egyptians: Poems, Narratives, and Manuals of Instruction, from the Third and Second Millennia B. C. Methuen & Company, Limited.

- Fabre, JP; Bariteau, M; Chalon, A; Thevenet, J (2001). "Possibilités de multiplication de pucerons Cedrobium laportei Remaudiére (Homoptera, Lachnidae) sur différentes provenances du genre Cedrus et sur deux hybrides d'espéces, perspectives d'utilisation en France". International Meeting on Sylviculture of Cork Oak (Quercus Suber L.) and Atlas Cedar (Cedrus Atlantica Manetti).

- Fady, B.; Lefèvre, F.; Reynaud, M.; Vendramin, G. G.; Bou Dagher-Kharrat, M.; Anzidei, M.; Pastorelli, R.; Savouré, A.; Bariteau, M. (1 October 2003). "Gene flow among different taxonomic units: evidence from nuclear and cytoplasmic markers in Cedrus plantation forests". TAG. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. Theoretische und Angewandte Genetik. 107 (6): 1132–1138. doi:10.1007/s00122-003-1323-z. ISSN 0040-5752. PMID 14523524.

- Farjon, Aljos (27 April 2010). A Handbook of the World's Conifers (2 Vols.). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004177185.

- Greuter, W.; Burdet, H.M.; Long, G., eds. (1984). "A critical inventory of vascular plants of the circum-mediterranean countries". ww2.bgbm.org. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum, Berlin. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Güner, Adil, ed. (9 April 2001). Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands: Flora of Turkey, Volume 11 (1 ed.). Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748614097.

- Hemery, Gabriel; Simblet, Sarah (21 October 2014). The New Sylva: A Discourse of Forest and Orchard Trees for the Twenty-First Century. A&C Black. ISBN 9781408835449.

- Howard, Frances (1 January 1955). Ornamental Trees: An Illustrated Guide to Their Selection and Care. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520007956.

- Mehdi, Ladjal (1 January 2001). "Variabilité de l'adaptation à la sécheresse des cèdres méditerranéens (Cedrus atlantica, C. Brevifolia et C. Libani) : aspects écophysiologiques". Doctorate Thesis, Université Henri Poincaré Nancy 1. Faculté des Sciences et Techniques – via www.theses.fr.

- Masri, Rania (1995), "The Cedars of Lebanon: significance, awareness and management of the Cedrus libani in Lebanon", Cedars awareness and salvation effort lecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology seminar on the environment in Lebanon, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Shackley, Myra (1 October 2004). "Managing the Cedars of Lebanon: Botanical Gardens or Living Forests?". Current Issues in Tourism. 7 (4–5): 417–425. doi:10.1080/13683500408667995. ISSN 1368-3500.

- Saint-Vincent, Bory de (1 January 1823). Dictionnaire classique d'histoire naturelle (in French). 3. Paris: Rey et Gravier. p. 299.

- Talhouk, Salma; Zurayk, Rami (2003). "Conifer conservation in Lebanon". Acta Horticulturae. 615 (615): 411–414. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.615.46.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cedrus libani. |

Online books, and library resources in your library and in other libraries about Cedrus libani

- Cedrus libani – information, genetic conservation units and related resources. European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN)