Hooded crow

The hooded crow (Corvus cornix) (also called hoodie)[2] is a Eurasian bird species in the genus Corvus. Widely distributed, it is also known locally as Scotch crow and Danish crow. In Ireland, it is called caróg liath or grey crow, as it is in the Slavic languages and in Danish. In German, it is called "mist crow" ("Nebelkrähe"). Found across Northern, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe, as well as parts of the Middle East, it is an ashy grey bird with black head, throat, wings, tail, and thigh feathers, as well as a black bill, eyes, and feet. Like other corvids, it is an omnivorous and opportunistic forager and feeder.

| Hooded crow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bodden, Baltic Sea, Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Corvus |

| Species: | C. cornix |

| Binomial name | |

| Corvus cornix | |

| |

It is so similar in morphology and habits to the carrion crow (Corvus corone), for many years they were considered by most authorities to be geographical races of one species. Hybridization observed where their ranges overlapped added weight to this view. However, since 2002, the hooded crow has been elevated to full species status after closer observation; the hybridisation was less than expected and hybrids had decreased vigour.[3][4] Within the hooded crow species, four subspecies are recognized, with one, the Mesopotamian crow, possibly distinct enough to warrant species status itself.

Taxonomy

The hooded crow was one of the many species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae and it bears its original name Corvus cornix.[5] The binomial name is derived from the Latin words corvus, "raven",[6] and cornix, "crow".[7] It was subsequently considered a subspecies of the carrion crow for many years,[8] hence known as Corvus corone cornix, due to similarities in structure and habits.

It is locally known as a hoodie in Scotland and as a grey crow in Northern Ireland.[9]

Subspecies

Four subspecies of the hooded crow are now recognised; previously, all were considered subspecies of Corvus corone. A fifth, the Sardinian hooded crow (C. c. sardonius) (Trischitta, 1939) has been listed, although it has been alternately partitioned between C. c. sharpii (most populations), C. c. cornix (Corsican population), and the Middle Eastern C. c. pallescens.

- The northern European hooded crow (C. c. cornix), the nominate race, occurs in the British Isles (principally Scotland and Ireland) and Europe, south to Corsica.

- The eastern Mediterranean hooded crow (C. c. pallescens) (Madarász, 1904) is found in Turkey and Egypt, and is a paler form as its name suggests.

- The southern European hooded crow (C. c. sharpii) (Oates, 1889) is named for English zoologist Richard Bowdler Sharpe. This is a paler grey form found from western Siberia through to the Caucasus region and Iran.[10]

- The Mesopotamian hooded crow (C. c. capellanus) (P. L. Sclater, 1877) is sometimes considered a separate species called the Mesopotamian crow or Iraqi pied crow. This distinctive form occurs in Iraq and southwestern Iran. It has very pale grey plumage, which looks almost white from a distance.[10] It is possibly distinct enough to be considered a separate species.[11]

Genetic difference from carrion crows

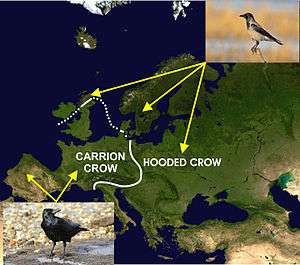

The hooded crow (Corvus cornix) and carrion crow (Corvus corone) are two closely related species whose geographical distribution across Europe is illustrated in the accompanying diagram. It is believed that this distribution might have resulted from the glaciation cycles during the Pleistocene, which caused the parent population to split into isolates which subsequently re-expanded their ranges when the climate warmed causing secondary contact.[4][12] Poelstra and coworkers sequenced almost the entire genomes of both species in populations at varying distances from the contact zone to find that the two species were genetically identical, both in their DNA and in its expression (in the form of mRNA), except for the lack of expression of a small portion (<0.28%) of the genome (situated on avian chromosome 18) in the hooded crow, which imparts the lighter plumage colouration on its torso.[4] Thus the two species can viably hybridize, and occasionally do so at the contact zone, but the all-black carrion crows on the one side of the contact zone mate almost exclusively with other all-black carrion crows, while the same occurs among the hooded crows on the other side of the contact zone. It is therefore clear that it is only the outward appearance of the two species that inhibits hybridization.[4][12] The authors attribute this to assortative mating (rather than to ecological selection), the advantage of which is not clear, and it would lead to the rapid appearance of streams of new lineages, and possibly even species, through mutual attraction between mutants. Unnikrishnan and Akhila[13] propose, instead, that koinophilia is a more parsimonious explanation for the resistance to hybridization across the contact zone, despite the absence of physiological, anatomical or genetic barriers to such hybridization.

Description

Except for the head, throat, wings, tail, and thigh feathers, which are black and mostly glossy, the plumage is ash-grey, the dark shafts giving it a streaky appearance. The bill and legs are black; the iris dark brown. Only one moult occurs, in autumn, as in other crow species. The male is the larger bird, otherwise the sexes are alike. Their flight is slow and heavy and usually straight. Their length varies from 48 to 52 cm (19 to 20 in). When first hatched, the young are much blacker than the parents. Juveniles have duller plumage with bluish or greyish eyes and initially a red mouth. Wingspan is 105 cm (41 in) and weight is on average 510 g.[14]

The hooded crow, with its contrasted greys and blacks, cannot be confused with either the carrion crow or rook, but the ![]()

Distribution

The hooded crow breeds in northern and eastern Europe, and closely allied forms inhabit southern Europe and western Asia. Where its range overlaps with carrion crow, as in northern Britain, Germany, Denmark, northern Italy, and Siberia, their hybrids are fertile. However, the hybrids are less well-adapted than purebred birds, and this is one of the reasons this species was split from the carrion crow.[16] Little or no interbreeding occurs in some areas, such as Iran and central Russia.

In the British Isles, the hooded crow breeds regularly in Scotland, the Isle of Man, and the Scottish Islands; it also breeds widely in Ireland. In autumn, some migratory birds arrive on the east coast of Britain. In the past, this was a more common visitor.[17]

Behaviour

Diet

The hooded crow is omnivorous, with a diet similar to that of the carrion crow, and is a constant scavenger. It drops molluscs and crabs to break them after the manner of the carrion crow, and an old Scottish name for empty sea urchin shells was "crow's cups".[17] On coastal cliffs, the eggs of gulls, cormorants, and other birds are stolen when their owners are absent, and this crow will enter the burrow of the puffin to steal eggs. It will also feed on small mammals, scraps, smaller birds, and carrion. The crow has the habit of hiding food, especially meat or nuts, in places such as rain gutters, flower pots, or in the earth under bushes, to feed on it later, sometimes on the insects that have meanwhile developed on it. Other crows often watch if another one hides food and then search this place later when the other crow has left.

Nesting

Nesting occurs later in colder regions: mid-May to mid-June in northwest Russia, Shetland, and the Faroe Islands, and late February in the Persian Gulf region.[10] In warmer parts of the European Archipelago, the clutch is laid in April.[18] The bulky stick nest is normally placed in a tall tree, but cliff ledges, old buildings, and pylons may be used. Nests are occasionally placed on or near the ground. The nest resembles that of the carrion crow, but on the coast, seaweed is often interwoven in the structure, and animal bones and wire are also frequently incorporated.[17][19] The four to six brown-speckled blue eggs are 4.3 cm × 3.0 cm (1.7 in × 1.2 in) in size and weigh 19.8 g (0.70 oz), of which 6% is shell.[14] The altricial young are incubated for 17–19 days by the female alone, that is fed by the male. They fledge after 32 to 36 days. Incubating females have been reported to obtain most of their own food and later that for their young.[20]

The typical lifespan is unknown, but that of the carrion crow is four years.[21] The maximum recorded age for a hooded crow is 16 years, and 9 months.[14]

This species is a secondary host of the parasitic great spotted cuckoo, the European magpie being the preferred host. However, in areas where the latter species is absent, such as Israel and Egypt, the hooded crow becomes the normal corvid host.[22]

This species, like its relative, is seen regularly killed by farmers and on grouse estates. In County Cork, Ireland, the county's gun clubs shot over 23,000 hooded crows in two years in the early 1980s.[17]

Status

The IUCN Red List does not distinguish the hooded crow from the carrion crow, but the two species together have an extensive range, estimated at 10 million km2 (3.8 million mi2), and a large population, including an estimated 14 to 34 million individuals in Europe alone. They are not believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), so are evaluated as least concern.[14][23] The carrion crow and hooded crow hybrid zone is slowly spreading northwest, but the hooded crow has on the order of three million territories in just Europe (excluding Russia).[19] This movement is also attested to by the fact that in April 2020 the hooded crow was redlisted in Sweden, where the Species Information Centre does distinguish between hooded and carrion crow.[24]

Cultural significance

In Celtic folklore, the bird appears on the shoulder of the dying Cú Chulainn,[25] and could also be a manifestation of the Morrígan, the wife of Tethra, or the Cailleach.[26] This idea has persisted, and the hooded crow is associated with fairies in the Scottish highlands and Ireland; in the 18th century, Scottish shepherds would make offerings to them to keep them from attacking sheep.[27] In Faroese folklore, a maiden would go out on Candlemas morn and throw a stone, then a bone, then a clump of turf at a hooded crow – if it flew over the sea, her husband would be a foreigner; if it landed on a farm or house, she would marry a man from there, but if it stayed put, she would remain unmarried.[28]

The old name of Royston crow originates from the days when this bird was a common winter visitor to southern England, the sheep fields around Royston, Hertfordshire, providing carcasses on which the birds could feed. The local newspaper, founded in 1855, is called The Royston Crow,[17] and the hooded crow also features on the town's coat of arms.[29]

The hooded crow is one of the 37 Norwegian birds depicted in the Bird Room of the Royal Palace in Oslo.[30] Jethro Tull mentions the hooded crow on the song "Jack Frost and the hooded crow" as a bonus track on the digitally remastered version of Broadsword and the Beast and on their The Christmas Album.[31]

In January 2014, a hooded crow along with yellow-legged gull each attacked one of two peace doves which Pope Francis allowed children to release in Vatican City.[32]

References

- BirdLife International (2017). "Corvus corone". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22706016A118784397. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22706016A118784397.en.

- Greenoak, F. (1979). All the Birds of the Air; the Names, Lore and Literature of British Birds. Book Club Associates, London.

- Parkin, David T. (2003). "Birding and DNA: species for the new millennium". Bird Study. 50 (3): 223–242. doi:10.1080/00063650309461316.

- Poelstra, Jelmer W.; Vijay, Nagarjun; Bossu, Christen M.; et al. (2014). "The genomic landscape underlying phenotypic integrity in the face of gene flow in crows" (PDF). Science. 344 (6190): 1410–1414. doi:10.1126/science.1253226. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24948738. Further reading:

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). v.1. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 105.

C. cineraſ cens, caplte gula alis caudaque nigris.

- "Corvus". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- Simpson, DP (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- Vere Benson, S. (1972). The Observer's Book of Birds. London: Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7232-1513-4.

- Macafee, CI, ed. (1996). A Concise Ulster Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-863132-3.

- Goodwin, D. (1983). Crows of the World. Queensland University Press, St Lucia, Qld. ISBN 978-0-7022-1015-0.

- Madge, Steve & Burn, Hilary (1994): Crows and jays: a guide to the crows, jays and magpies of the world. A&C Black, London. ISBN 0-7136-3999-7

- de Knijf, Peter (2014). "How carrion and hooded crows defeat Linnaeus's curse". Science. 344 (6190): 1345–1346. doi:10.1126/science.1255744. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24948724.

- Poelstra, Jelmer W.; Vijay, Nagarjun; Bossu, Christen M.; et al. (2014). "The genomic landscape underlying phenotypic integrity in the face of gene flow in crows" (PDF). Science. 344 (6190): 1410–1414. doi:10.1126/science.1253226. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24948738.

The phenotypic differences between Carrion and Hooded Crows across the hybridization zone in Europe are unlikely to be due to assortative mating.

— Commentary by Mazhuvancherry K. Unnikrishnan and H. S. Akhila - "Hooded Crow Corvus cornix [Linnaeus, 1758]". BTOWeb BirdFacts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- Mullarney, Killian; v, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (2001). Birds of Europe. Princeton Field Guides. Princeton University Press. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-691-05054-6.

- Jones, Steve (1999): Almost Like A Whale: The Origin Of Species Updated. Doubleday, Garden City. ISBN 978-0-385-40985-8

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 418–425. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- Evans, G (1972). The Observer's Book of Birds' Eggs. London: Warne. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7232-0060-4.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M., eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1478–1480. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- Yom-Tov, Yoram (June 1974). "The effect of food and predation on breeding density and success, clutch size and laying date of the crow (Corvus corone L.)". Journal of Animal Ecology. 43 (2): 479–498. doi:10.2307/3378. JSTOR 3378.

- "Carrion Crow Corvus corone [Linnaeus, 1758]". BTOWeb BirdFacts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- Snow & Perrins (1998) 873–4

- BirdLife International (2004). "Corvus corone". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004: e.T22706016A26497956. Retrieved 5 May 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- https://www.artdatabanken.se/aktuellt/artdatabankens-nyheter/fagelarter-pa-rodlistan/

- Armstrong, Edward A. (1970) [1958]. The Folklore of Birds. Dover. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-486-22145-8.

- Armstrong, p. 83

- Ingersoll, Ernest (1923). Birds in legend, fable and folklore. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 165. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- Armstrong, Edward A. (1970) [1958]. The Folklore of Birds. Dover. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-486-22145-8.

- "Royston Town Council (Herts)". Civic Heraldry of England and Wales.

- "The Bird Room". The Norwegian Royal Family - Official Website. The Norwegian Royal Family. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- Anderson, Ian (2007). "The Jethro Tull Christmas Album Special Edition Features Bonus DVD in USA!". Jethro Tull - The Official Website. Jethro Tull. Archived from the original on 2008-03-04. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/01/26/how-killer-birds-forced-pope-francis-to-change-a-vatican-tradition-releasing-doves-for-peace/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corvus cornix. |