Frederick the Great

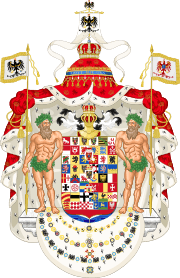

Frederick II (German: Friedrich II.; 24 January 1712 – 17 August 1786) ruled the Kingdom of Prussia from 1740 until 1786, the longest reign of any Hohenzollern king at 46 years.[lower-alpha 1] His most significant accomplishments during his reign included his military victories, his reorganization of Prussian armies, his patronage of the arts and the Enlightenment and his success in the Seven Years' War. Frederick was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled King in Prussia and declared himself King of Prussia after achieving sovereignty over most historically Prussian lands in 1772. Prussia had greatly increased its territories and became a leading military power in Europe under his rule. He became known as Frederick the Great (German: Friedrich der Große) and was nicknamed Der Alte Fritz ("Old Fritz") by the Prussian people and eventually the rest of Germany.[1]

| Frederick II | |

|---|---|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Portrait by Anton Graff, 1781 | |

| |

| Reign | 31 May 1740 – 17 August 1786 |

| Predecessor | Frederick William I |

| Successor | Frederick William II |

| Chief Ministers | See list

|

| Born | 24 January 1712 Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 17 August 1786 (aged 74) Potsdam, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Burial | Sanssouci, Potsdam |

| Spouse | Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern |

| House | Hohenzollern |

| Father | Frederick William I of Prussia |

| Mother | Sophia Dorothea of Hanover |

| Religion | Calvinism |

| Signature |  |

In his youth, Frederick was more interested in music and philosophy than the art of war. Nonetheless, upon ascending to the Prussian throne he attacked Austria and claimed Silesia during the Silesian Wars, winning military acclaim for himself and Prussia. Toward the end of his reign, Frederick physically connected most of his realm by acquiring Polish territories in the First Partition of Poland. He was an influential military theorist whose analysis emerged from his extensive personal battlefield experience and covered issues of strategy, tactics, mobility and logistics.

Considering himself "the first servant of the state",[2] Frederick was a proponent of enlightened absolutism. He modernized the Prussian bureaucracy and civil service and pursued religious policies throughout his realm that ranged from tolerance to segregation.[3] He reformed the judicial system and made it possible for men not of noble status to become judges and senior bureaucrats. Frederick also encouraged immigrants of various nationalities and faiths to come to Prussia, although he enacted oppressive measures against Polish Catholic subjects in West Prussia. Frederick supported arts and philosophers he favored as well as allowing complete freedom of the press and literature.[4] Most modern biographers agree that Frederick was primarily homosexual. Frederick is buried at his favorite residence, Sanssouci in Potsdam. Because he died childless, Frederick was succeeded by his nephew Frederick William II.

Nearly all 19th-century German historians made Frederick into a romantic model of a glorified warrior, praising his leadership, administrative efficiency, devotion to duty and success in building up Prussia to a great power in Europe. Historian Leopold von Ranke was unstinting in his praise of Frederick's "heroic life, inspired by great ideas, filled with feats of arms ... immortalized by the raising of the Prussian state to the rank of a power". Johann Gustav Droysen was even more extolling.[5] Frederick remained an admired historical figure through Germany's defeat in World War I. The Nazis glorified him as a great German leader pre-figuring Adolf Hitler, who personally idolized him.[6]

Associations with him became far less favorable after the fall of the Nazis, largely due to his status as one of their symbols.[7] However, historians in the 21st century now again view Frederick as one of the finest generals of the 18th century, one of the most enlightened monarchs of his age and a highly successful and capable leader who built the foundation for the Kingdom of Prussia to become a great power that would contest the Austrian Habsburgs for leadership among the German states.

Youth

Frederick, the son of Frederick William I and his wife, Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, was born in Berlin on 24 January 1712, baptised with the single name Friedrich. The birth was welcomed by his grandfather, Frederick I, with more than usual pleasure, as his two previous grandsons had both died in infancy. With the death of Frederick I in 1713, his son Frederick William became King in Prussia, thus making young Frederick the crown prince. The new king wished for his sons and daughters to be educated not as royalty, but as simple folk. He had been educated by a Frenchwoman, Madame de Montbail, who later became Madame de Rocoulle, and he wished that she educate his children.

Frederick William I, popularly dubbed the Soldier King, had created a large and powerful army led by his famous "Potsdam Giants", carefully managed his treasury, and developed a strong centralized government. He was prey to a violent temper (in part due to porphyria) and ruled Brandenburg-Prussia with absolute authority. As Frederick grew, his preference for music, literature and French culture clashed with his father's militarism, resulting in Frederick William frequently beating and humiliating him. In contrast, Frederick's mother Sophia was polite, charismatic and learned. Her father, George Louis of Brunswick-Lüneburg, succeeded to the British throne as King George I in 1714.

Frederick was brought up by Huguenot governesses and tutors and learned French and German simultaneously. In spite of his father's desire that his education be entirely religious and pragmatic, the young Frederick, with the help of his tutor Jacques Duhan, procured for himself a three thousand volume secret library of poetry, Greek and Roman classics, and French philosophy to supplement his official lessons.[8]

Although Frederick William I was raised a Calvinist, he feared he was not one of God's elect. To avoid the possibility of Frederick being motivated by the same concerns, the king ordered that his heir not be taught about predestination. Nevertheless, although Frederick was largely irreligious, he to some extent appeared to adopt this tenet of Calvinism. Some scholars have speculated that he did this to spite his father.[9]

Crown Prince

In the mid-1720s, Queen Sophia Dorothea attempted to arrange the marriage of Frederick and his sister Wilhelmine to her brother King George II's children Amelia and Frederick, respectively.[10] Fearing an alliance between Prussia and Great Britain, Field Marshal von Seckendorff, the Austrian ambassador in Berlin, bribed the Prussian Minister of War, Field Marshal von Grumbkow, and the Prussian ambassador in London, Benjamin Reichenbach. The pair slandered the British and Prussian courts in the eyes of the two kings. Angered by the idea of the effete Frederick's being so honored by Britain, Frederick William presented impossible demands to the British, such as "securing Prussia's rights to the principalities of Jülich-Berg", and after 1728, only Berg,[11] which led to the collapse of the marriage proposal.[12]

Frederick found an ally in his sister, Wilhelmine, with whom he remained close for life; he was later devastated by her death in 1758. At age 16, Frederick formed an attachment to the king's 17-year-old page, Peter Karl Christoph von Keith. Wilhelmine recorded that the two "soon became inseparable. Keith was intelligent, but without education. He served my brother from feelings of real devotion, and kept him informed of all the king's actions."[13] The friendship was apparently of a homosexual nature, and as a result thereof, Keith was sent away to an unpopular regiment near the Dutch frontier, while Frederick was temporarily sent to his father's hunting lodge at Königs Wusterhausen in order "to repent of his sin."[14]

Katte affair

Soon after his previous affair, he became close friends with Hans Hermann von Katte, a Prussian officer several years older than Frederick who served as one of his tutors.[14] When he was 18, Frederick plotted to flee to England with Katte and other junior army officers. While the royal retinue was near Mannheim in the Electorate of the Palatinate, Robert Keith, Peter Keith's brother, had an attack of conscience when the conspirators were preparing to escape and begged Frederick William for forgiveness on 5 August 1730;[15] Frederick and Katte were subsequently arrested and imprisoned in Küstrin. Because they were army officers who had tried to flee Prussia for Great Britain, Frederick William leveled an accusation of treason against the pair. The king briefly threatened the crown prince with execution, then considered forcing Frederick to renounce the succession in favour of his brother, Augustus William, although either option would have been difficult to justify to the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire.[16] The king forced Frederick to watch the beheading of his confidant Katte at Küstrin on 6 November, leading the crown prince to faint just before the fatal blow.[17][14]

Frederick was granted a royal pardon and released from his cell on 18 November, although he remained stripped of his military rank.[18] Instead of returning to Berlin, however, he was forced to remain in Küstrin and began rigorous schooling in statecraft and administration for the War and Estates Departments on 20 November. Tensions eased slightly when Frederick William visited Küstrin a year later, and Frederick was allowed to visit Berlin on the occasion of his sister Wilhelmine's marriage to Margrave Frederick of Bayreuth on 20 November 1731. The crown prince returned to Berlin after finally being released from his tutelage at Küstrin on 26 February 1732.

Marriage and War of the Polish Succession

Frederick William considered marrying Frederick to Elisabeth of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, the niece of Empress Anna of Russia, but this plan was ardently opposed by Prince Eugene of Savoy. Frederick himself proposed marrying Maria Theresa of Austria in return for renouncing the succession. Instead, Eugene persuaded Frederick William, through Seckendorff, that the crown prince marry Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern, a Protestant relative of the Austrian Habsburgs.[19] Although Frederick wrote to his sister that, "There can be neither love nor friendship between us,"[20] and he considered suicide, he went along with the wedding on 12 June 1733 despite this. He had little in common with his bride and resented the political marriage as an example of the Austrian political interference which had plagued Prussia since 1701. Once Frederick secured the throne in 1740, he prevented Elisabeth from visiting his court in Potsdam, granting her instead Schönhausen Palace and apartments at the Berliner Stadtschloss. Frederick bestowed the title of the heir to the throne, "Prince of Prussia", on his brother Augustus William; despite this, his wife remained devoted to him.[21] In their early married life, the royal couple resided at the Crown Prince's Palace in Berlin. Although Frederick gave Elisabeth Christine all the honors befitting her station, he rarely saw her during his reign and never showed her any affection.

Frederick was restored to the Prussian Army as Colonel of the Regiment von der Goltz, stationed near Nauen and Neuruppin. When Prussia provided a contingent of troops to aid the Army of the Holy Roman Empire during the War of the Polish Succession, Frederick studied under Reichsgeneralfeldmarschall Prince Eugene of Savoy during the campaign against France on the Rhine; he noted the weakness of the Imperial Army under the command of the Archduchy of Austria, something that he would capitalize on at Austria's expense when he later took the throne.[22] Frederick William, weakened by gout brought about by the campaign and seeking to reconcile with his heir, granted Frederick Schloss Rheinsberg in Rheinsberg, north of Neuruppin. In Rheinsberg, Frederick assembled a small number of musicians, actors and other artists. He spent his time reading, watching dramatic plays, composing and playing music, and regarded this time as one of the happiest of his life. Frederick formed the Bayard Order to discuss warfare with his friends; Heinrich August de la Motte Fouqué was made the grand master of the gatherings.

The works of Niccolò Machiavelli, such as The Prince, were considered a guideline for the behavior of a king in Frederick's age. In 1739, Frederick finished his Anti-Machiavel, an idealistic refutation of Machiavelli. It was written in French and published anonymously in 1740, but Voltaire distributed it in Amsterdam to great popularity.[23] Frederick's years dedicated to the arts instead of politics ended upon the 1740 death of Frederick William and his inheritance of the Kingdom of Prussia. Frederick and his father were more or less reconciled at the latter's death, and Frederick later admitted, despite their constant conflict, that Frederick William had been an effective ruler: "What a terrible man he was. But he was just, intelligent, and skilled in the management of affairs... it was through his efforts, through his tireless labor, that I have been able to accomplish everything that I have done since."[24]

Inheritance

In one defining respect Frederick would come to the throne with an exceptional inheritance. A Prussian population estimated at 2.24 million might not be enough to confer great power status, but it turned out that an army of 80,000 men could be.[25] The ratio of one soldier for every 28 citizens was far higher than the one-to-310 in Great Britain, another great power of this period.[25] Moreover, the Prussian infantry trained by Frederick William I were, at the time of Frederick's accession, arguably unrivaled in discipline and firepower. By 1770, after two decades of punishing war alternating with intervals of peace, Frederick had doubled the size of the huge army he had inherited, and which during his reign would consume 86% of the state budget.[25] The situation is summed up in a widely translated and quoted aphorism attributed to Mirabeau, who asserted in 1786 that Prussia under Frederick was not a state in possession of an army, but an army in possession of a state ("La Prusse n’est pas un pays qui a une armée, c’est une armée qui a un pays").[26][27]

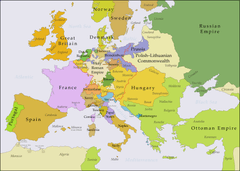

Reign

Prince Frederick was twenty-eight years old when his father Frederick William I died and he ascended to the throne of Prussia.[28] Before his accession, Frederick was told by D'Alembert, "The philosophers and the men of letters in every land have long looked upon you, Sire, as their leader and model." Such devotion, however, had to be tempered by political realities. When Frederick ascended the throne as "King in Prussia" in 1740, his realm consisted of scattered territories, including Cleves, Mark, and Ravensberg in the west of the Holy Roman Empire; Brandenburg, Hither Pomerania, and Farther Pomerania in the east of the Empire; and the Kingdom of Prussia, the former Duchy of Prussia, outside of the Empire bordering the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was titled King in Prussia because this was only part of historic Prussia; he was to declare himself King of Prussia after acquiring most of the rest in 1772.

War of the Austrian Succession

Frederick's goal was to modernize and unite his vulnerably disconnected lands; toward this end, he fought wars mainly against Austria, whose Habsburg dynasty reigned as Holy Roman Emperors almost continuously from the 15th century until 1806. Frederick established Prussia as the fifth and smallest European great power by using the resources his frugal father had cultivated.

Upon succeeding to the throne on 31 May 1740,[29] and desiring the prosperous Austrian province of Silesia (to which Prussia had a minor claim), Frederick declined to endorse the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, a legal mechanism to ensure the inheritance of the Habsburg domains by Maria Theresa of Austria, daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI. Thus, upon the death of Charles VI on 29 October 1740,[30] Frederick disputed the succession of the 23-year-old Maria Theresa to the Habsburg lands, while simultaneously making his own claim on Silesia. Accordingly, the First Silesian War (1740–1742, part of the War of the Austrian Succession) began on 16 December 1740 when Frederick invaded and quickly occupied the province.[28] Frederick was worried that if he did not move, Augustus III, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, would seek to connect his own disparate lands through Silesia. The Prussian king quickly snatched the territory, using as justification an obscure treaty from 1537 between the Hohenzollern and the Piast dynasty of Brieg (Brzeg).

Frederick occupied Silesia, except for three fortresses at Glogau, Brieg and Breslau,[31] in just seven weeks, despite poor roads and bad weather.[28] The fortress at Ohlau fell almost immediately and became the winter quarters for Frederick's army.[28] In late March 1741, Frederick set out on campaign again, but was forced to fall back by a sudden surprise attack by the Austrians. The first real battle Frederick faced in Silesia was the Battle of Mollwitz on 10 April 1741.[32] Though Frederick had actually served under Prince Eugene of Savoy, this was the first time he had commanded an army. In the course of the battle, believing his forces had been defeated by the Austrians, Frederick galloped away to avoid capture,[33] leaving Field Marshal Kurt Schwerin in command. In actuality, the Prussians had won the battle at that very moment. Frederick would later admit to humiliation at his abdication of command[34] and would state: "Mollwitz was my school." Disappointed with the performance of his cavalry, whose training his father had neglected in favor of the infantry, Frederick spent much of his time in Silesia establishing a new doctrine for them.[35]

In early September 1741, the French entered the war against Austria, and together with their allies, the Electorate of Bavaria, marched on Prague.[36] Meanwhile, Frederick sponsored the candidacy of his ally Charles of Bavaria to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. Charles was crowned on 2 February 1742 and claimed the crown of Bohemia as his own. With Prague under threat, the Austrians pulled their army out of Silesia to defend Bohemia. When Frederick pursued them into Bohemia and blocked their path to Prague, the Austrians counter-attacked on 17 May 1742. However, Frederick's retrained cavalry proved effective, and ultimately Prussia claimed victory at the Battle of Chotusitz.[34] After this dramatic victory, and with the Franco-Bavarian forces having captured Prague, Frederick forced the Austrians to seek peace. The terms of the Treaty of Breslau between Austria and Prussia, negotiated in June 1742, gave Prussia all of Silesia and Glatz County,[34] with the Austrians retaining only the portion called Austrian or Czech Silesia. Prussian possession of Silesia gave the kingdom control over the navigable Oder River as well as nearly doubling its population, economy and territory. In 1744, Frederick also inherited the minor territory of East Frisia on the North Sea coast of Germany after its last ruler died without issue.

By 1743, the Austrians had subdued Bavaria and driven the French out of Bohemia. Frederick strongly suspected Maria Theresa would resume war in an attempt to recover Silesia. Accordingly, he renewed his alliance with France and preemptively invaded Bohemia in August 1744, beginning the Second Silesian War.[37] By late August 1744, all of Frederick's columns had crossed the Bohemian frontier.[38] Frederick marched straight for Prague and laid siege to the city.[39][40] On 11 September 1744, the Prussians began a three-day artillery bombardment of Prague, which fell a few days later.[34] Three days after this victory,[41] Frederick's troops were again on the march into the heart of central Bohemia.[34] However, the Austrians refused to directly engage with Frederick's army and harassed his supply lines, eventually forcing him to withdraw to Silesia as winter approached. With the death of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII of Bavaria in January 1745, Maria Theresa's husband Francis of Lorraine was elected emperor and Saxony joined the Austrians' side against Frederick.

On 4 June 1745, Frederick trapped a joint force of Saxons and Austrians that had crossed the mountains to invade Silesia. After allowing them across ("If you want to catch a mouse, leave the trap open"), Frederick then pinned down the enemy force and defeated them at the Battle of Hohenfriedberg.[42] Pursuing the Austrians into Bohemia, Frederick caught the enemy on 30 September 1745 and delivered a flanking attack on the Austrian right wing at the Battle of Soor, which set the Austrians to flight.[43] Frederick then turned towards Dresden when he learned the Saxons were preparing to march on Berlin. However, on 15 December 1745, the Saxons were soundly defeated at the Battle of Kesselsdorf by Prussian commander Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau. After linking up his army with Leopold's, Frederick occupied the Saxon capitol of Dresden, forcing the Saxon Elector (and King of Poland) Augustus III to capitulate.

Once again, Frederick's stunning victories on the battlefield compelled his enemies to sue for peace. Under the terms of the Treaty of Dresden, signed on 25 December 1745, Austria was forced to adhere to the terms of the Treaty of Breslau giving Silesia to Prussia.[44]

Seven Years' War

Habsburg Austria and Bourbon France, traditional enemies, allied together in the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756 following the collapse of the Anglo-Austrian Alliance. Frederick swiftly made an alliance with Great Britain at the Convention of Westminster.[45] When the neighboring countries began conspiring against him, Frederick determined to strike first. On 29 August 1756, his well-prepared army preemptively invaded Saxony,[46] beginning the Third Silesian War and the larger Seven Years' War, both of which lasted until 1763.[lower-alpha 2] He faced widespread criticism for his attack on neutral Saxony and his forcible incorporation of the Saxon forces into the Prussian army following the Siege of Pirna in October 1756.[47] While the Prussian invasion of Saxony was successful, it took uncharacteristically long to complete, costing Prussia the initiative. Frederick's subsequent 1757 invasion of Austrian Bohemia, though initially successful, ended in his first defeat at the Battle of Kolin and forced him into retreat. However, when the French and the Austrians pursued him into Saxony and Silesia, Frederick decisively defeated them at the battles of Rossbach and Leuthen. Frederick hoped these two great victories would force Austria to negotiate, but Maria Theresa was determined not to make peace until she had recovered Silesia, and the war continued. Despite its excellent performance, the Prussian army became increasingly stretched thin by various costly battles.

Facing a coalition of enemies including Austria, France, Russia, Saxony and Sweden, and allied only with Great Britain, Hesse, Brunswick, and Hanover, Frederick narrowly kept Prussia in the war despite having his territories repeatedly invaded. He suffered some severe defeats and was frequently at his last gasp, but he always managed to recover. His position became even more desperate in 1761 when Britain, having profited by gains in India and the Americas, ended its financial support for Prussia after the death of King George II, Frederick's uncle. On 6 January 1762, he wrote to Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein, "We ought now to think of preserving for my nephew, by way of negotiation, whatever fragments of my territory we can save from the avidity of my enemies".[48] With the Russians slowly advancing towards Berlin, it looked as though Prussia was about to collapse.

The sudden death of Empress Elizabeth of Russia in January 1762 led to the succession of Peter III, her Germanized pro-Prussian nephew (previously Duke of Holstein-Gottorp).[49] This "Miracle of the House of Brandenburg" led to the collapse of the anti-Prussian coalition; Peter immediately ended the Russian occupation of East Prussia and Pomerania, returning them to Frederick. One of Peter III's first diplomatic endeavors was to seek a Prussian title from Frederick, which Frederick naturally obliged. Peter III was so enamored of Frederick that he not only offered him the full use of a Russian corps for the remainder of the war against Austria, he also wrote to Frederick that he would rather have been a general in the Prussian army than Tsar of Russia.[50] More significantly, Russia's about-face from an enemy of Prussia to its patron rattled the leadership of Sweden, who, seeing the writing on the wall, hastily made peace with Frederick as well.[51] With the threat to his eastern borders over, and France also seeking peace after its defeats by Britain, Frederick was able to fight the Austrians to a stalemate and finally brought them to the peace table. While the ensuing Treaty of Hubertusburg simply returned the European borders to what they had been before the Seven Years' War, Frederick's ability to retain Silesia in spite of the odds earned Prussia admiration throughout the German-speaking territories. A year following the Treaty of Hubertusberg, Catherine the Great, Peter III's widow and usurper, signed an eight-year alliance with Prussia.[52]

Frederick's ultimate success in the Seven Years' War came at a heavy price, both to him and Prussia. According to the Anglo-Prussian Convention, Frederick received from 1758 till 1762 an annual ₤670,000 in British subsidies, which ceased when Frederick allied with Peter III, who planned to solve the Gottorp question and attacked Danish Holstein in 1762 after the death of Frederick Charles.[53][54][55][56][57] During the war Frederick devalued the Prussian coin five times in order to finance the war; debased coins were produced (with the help of Veitel Heine Ephraim and Daniel Itzig, mintmasters in Leipzig) and spread outside Prussia: in Saxony, Poland, and Kurland.[58][59][60] Saxony, occupied by Prussia for most of the conflict, was bled dry to support the war effort. While Prussia lost no territory, her population and army were severely depleted by constant combat and invasions by Austria, Russia and Sweden. Many of Frederick's closest friends (as well as his sister Wilhelmine, his brother Augustus William and his mother) and the best of his officer corps were lost in the war. By 1772, with his economy largely recovered, Frederick had managed to bring his army up to 190,000 men (making it the third-largest army in Europe), but almost none of the officers were veterans of his generation, and the King's attitude towards them was extremely harsh.[61]

First Partition of Poland

Frederick had despised the Poles since his youth, and he is known to have expressed numerous anti-Polish statements,[62] referring to Polish society as "stupid", and remarking that "all these people with surnames ending with -ski, deserve only contempt".[63] He passionately hated everything associated with Poland, while justifying his hatred and territorial expansionism with the ideals of the Enlightenment.[64] He described Poles as "slovenly Polish trash";[65][lower-alpha 3] referring to them in a letter from 1735 as "dirty" and "vile apes",[67] and compared the Polish peasants to the Iroquois.[68]

Frederick undertook the conquest of Polish territory under the pretext of an enlightened civilizing mission, given his disparagement of Poland and its ruling elite, all of which provided a convenient entree for the "sanguine meliorism" of the Enlightenment and heightened assurance in the "distinctive merits of the 'Prussian way'".[69][70] He prepared the ground for the partition of Poland-Lithuania in 1752 at latest, hoping to gain a territorial bridge between Pomerania, Brandenburg, and his East Prussian provinces.[71] Frederick was himself partly responsible for the weakness of the Polish government, having inflated its currency by his use of Polish coin dies obtained during the conquest of Saxony in 1756: the profits exceeded 25 million thalers, twice the peacetime national budget of Prussia.[72][73] He opposed attempts of political reform in Poland, and his troops bombarded customs ports on the Vistula, thwarting Polish efforts to create a modern fiscal system.[74] As early as 1731 Frederick had suggested that his country would benefit from annexing Polish Prussia in order to join the separated territories of his own kingdom.[75]

According to Scott, Frederick was eager to exploit Poland economically as part of his wider aim of enriching Prussia. Scott views this as a continuation of his previous violations of Polish territory in 1759 and 1761 and raids within Greater Poland until 1765.

Lewitter says: "The conflict over the rights of religious dissenters [in Poland] had led to civil war and foreign intervention." Out of 11–12 million people in Poland, 200,000 were Protestants and 600,000 Eastern Orthodox. The Protestant dissidents were still free to practice their religion, although their schools were shut down.[76] All dissidents could own property, but Poland increasingly reduced their civic rights after a period of considerable religious and political freedoms. They were allowed to serve in the army and vote in elections, but were barred from public offices and the Polish Parliament (Sejm), and during the 1760s their importance became out of proportion compared to their numbers. Frederick exploited this conflict as means to keep Poland weak and divided.[73]

Empress Catherine II of Russia was staunchly opposed to Prussia, and in response Frederick opposed Russia, whose troops had been allowed to freely cross the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Seven Years' War of 1756–63. Despite their personal hostility, Frederick and Catherine signed a defensive alliance in 1764 that guaranteed Prussian control of Silesia in return for Prussian support for Russia against Austria or the Ottoman Empire. Catherine's candidate for the Polish throne, Stanisław August Poniatowski, was then elected King of Poland in September of that year with Frederick's support, and she gained control of Polish politics.

Frederick became concerned, however, after Russia gained significant influence over Poland in the Repnin Sejm of 1767, a position which also threatened Austria and the Ottoman Turks. In the ensuing Russo-Turkish War (1768–74), Frederick supported Catherine with a subsidy of 300,000 rubles, albeit with reluctance as he did not want Russia to become even stronger through acquisitions of Ottoman territory. The Prussian king achieved a rapprochement with the Austrian Emperor Joseph and chancellor Kaunitz.

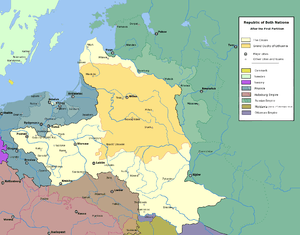

After Russia occupied the Danubian Principalities in 1769–70, Frederick's representative in Saint Petersburg, his brother Prince Henry, convinced Frederick and Maria Theresa that the balance of power would be maintained by a tripartite division of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth instead of Russia taking land from the Ottomans. They agreed to the First Partition of Poland in 1772, which took place without war. Frederick claimed most of the Polish province of Royal Prussia. Prussia annexed 20,000 square miles (52,000 km2) and 600,000 inhabitants, the least of the partitioning powers.[77] However, Prussia's Polish territory was also the best-developed economically. The newly created province of West Prussia connected East Prussia and Farther Pomerania and granted Prussia control of the mouth of the Vistula River. Frederick also invited German immigrants to the province,[78] hoping they would displace the Poles.[79] Maria Theresa had only reluctantly agreed to the partition, to which Frederick sarcastically commented, "she cries, but she takes".[68]

Frederick himself tried further propaganda to justify the Partition, portraying the acquired provinces as underdeveloped and improved by Prussian rule. According to Karin Friedrich these claims were accepted for a long time in German historiography and sometimes still reflected in modern works.[80] Frederick did not justify his conquests on an ethnic basis, however, unlike later nationalist, 19th-century German historians. Dismissive of contemporary German culture, Frederick instead pursued an imperialist policy, acting on the security interests of his state.[81] Frederick II settled 300,000 colonists in territories he had conquered, and enforced Germanization.[82]

After the first partition Frederick engaged in plunder of Polish property, confiscating Polish estates and monasteries to support German colonization, and in 1786 he ordered forced buy-outs of Polish holdings.[83] The new strict tax system and bureaucracy was particularly disliked among the Polish population, as was the compulsory military service in the army, which did not exist previously in Poland.[84] Frederick abolished the gentry's freedom from taxation and restricted its power.[85] Royal estates formerly belonging to the Polish Crown were redistributed to German landowners, reinforcing Germanization.[86] Both Protestant and Roman Catholic teachers (mostly Jesuits) taught in West Prussia, and teachers and administrators were encouraged to be able to speak both German and Polish.[78] Economic exploitation of Poland, especially by Prussia and Austria, followed the territorial seizures.

Frederick looked upon many of his new Polish citizens with scorn, but carefully concealed that scorn when actually dealing with them. Frederick's long-term goal was to remove all Polish people from his territories, both peasants and nobility. He sought to expel the nobles through an oppressive tax system and the peasantry by eradicating the Polish national character of the rural population by mixing them with Germans invited in their thousands by promises of free land. By such means, Frederick boasted he would "gradually...get rid of all Poles".[87][88]

Frederick wrote that Poland had "the worst government in Europe with the exception of Turkey".[68] After a prolonged visit to West Prussia in 1773, Frederick informed Voltaire of his findings and accomplishments: "I have abolished serfdom, reformed the savage laws, opened a canal which joins up all the main rivers; I have rebuilt those villages razed to the ground after the plague in 1709. I have drained the marshes and established a police force where none existed. ... [I]t is not reasonable that the country which produced Copernicus should be allowed to moulder in the barbarism that results from tyranny. Those hitherto in power have destroyed the schools, thinking that the uneducated people are easily oppressed. These provinces cannot be compared with any European country—the only parallel would be Canada."[89] However, in a letter to his favorite brother, Prince Henry, Frederick admitted that the Polish provinces were economically profitable:

- It is a very good and advantageous acquisition, both from a financial and a political point of view. In order to excite less jealousy I tell everyone that on my travels I have seen just sand, pine trees, heath land and Jews. Despite that there is a lot of work to be done; there is no order, and no planning and the towns are in a lamentable condition.[90]

Frederick also sent in Jesuits to open schools, and befriended Ignacy Krasicki, whom he asked to consecrate St. Hedwig's Cathedral in 1773. He also advised his successors to learn Polish, a policy followed by the Hohenzollern dynasty until Frederick III decided not to let the future William II learn the language.[78]

War of the Bavarian Succession

_Joseph_II_als_Mitregent_seiner_Mutter.jpg)

Late in his life Frederick involved Prussia in the low-scale War of the Bavarian Succession in 1778, in which he stifled Austrian attempts to exchange the Austrian Netherlands for Bavaria.[91] For their part, the Austrians tried to pressure the French to participate in the War of Bavarian Succession since there were guarantees under consideration related to the Peace of Westphalia, clauses which linked the Bourbon dynasty of France and the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty of Austria. Unfortunately for the Austrian Emperor Joseph II, the French were unable to provide sufficient manpower and resources to the endeavor since they were already struggling on the North American continent against the British, aiding the American cause for independence in the process. Frederick ended up as a beneficiary of the French and British struggle across the Atlantic, as Austria was left more or less isolated.[92]

Moreover, Saxony and Russia, both of which had been Austria's allies in the Seven Years' War, were now allied with Prussia. Although Frederick was weary of war in his old age, he was determined not to allow the Austrians dominance in German affairs. Frederick and Prince Henry marched the Prussian army into Bohemia to confront Joseph's army, but the two forces ultimately descended into a stalemate, largely living off the land and skirmishing rather than actively attacking each other. Frederick's longtime rival Maria Theresa (Joseph's mother and co-ruler) did not want a new war with Prussia, and secretly sent messengers to Frederick to discuss peace negotiations. Finally, Catherine II of Russia threatened to enter the war on Frederick's side if peace was not negotiated, and Joseph reluctantly dropped his claim to Bavaria. When Joseph tried the scheme again in 1784, Frederick created the Fürstenbund, allowing himself to be seen as a defender of German liberties, in contrast to his earlier role of attacking the imperial Habsburgs. In the process of checking Joseph II's attempts to acquire Bavaria, Frederick enlisted two very important players, the Electors of Hanover and Saxony along with several other second-rate German princes. Perhaps even more significant, Frederick benefited from the defection of the senior prelate of the German Church (Archbishop of Mainz) who was also the arch-chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire, which further strengthened Frederick and Prussia's standing amid the German states.[93]

Policies

Military theory

Contrary to what his father had feared, Frederick proved himself very courageous in battle (with the exception of his first battlefield experience, Mollwitz). He frequently led his military forces personally and had six horses shot from under him during battle. During his reign he commanded the Prussian Army at sixteen major battles (most of which were victories for him) and various sieges, skirmishes and other actions. He is often admired as one of the greatest tactical geniuses of all time, especially for his usage of the oblique order of battle, in which attack is focused on one flank of the opposing line, allowing a local advantage even if his forces were outnumbered overall (which they often were). Even more important were his operational successes, especially preventing the unification of numerically superior opposing armies and being at the right place at the right time to keep enemy armies out of Prussian core territory.

Napoleon Bonaparte saw the Prussian king as the greatest tactical genius of all time;[94] after Napoleon's victory of the Fourth Coalition in 1807, he visited Frederick's tomb in Potsdam and remarked to his officers, "Gentlemen, if this man were still alive I would not be here".[95] Napoleon frequently "pored through Frederick's campaign narratives and had a statuette of him placed in his personal cabinet."[96] Frederick and Napoleon are perhaps the most admiringly quoted military leaders in Clausewitz' On War. Clausewitz praised particularly the quick and skillful movement of his troops.[97]

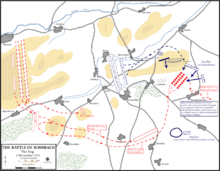

Frederick the Great's most notable and decisive military victories on the battlefield were the Battles of Hohenfriedberg, fought during the War of Austrian Succession in June 1745;[98] the Battle of Rossbach, where Frederick defeated a combined Franco-Austrian army of 41,000 with a mere 21,000 soldiers (10,000 dead for the Franco-Austrian side with only 550 casualties for Prussia);[99] and the Battle of Leuthen, which was a follow up victory to Rossbach pitting Frederick's 36,000 troops against Charles of Lorraine's Austrian force of 80,000—Frederick's masterful strategy and tactics at Leuthen inflicted 7,000 casualties upon the Austrians and yielded 20,000 prisoners.[100]

Frederick the Great believed that creating alliances was necessary, as Prussia did not have the comparable resources of nations like France or Austria. After the Seven Years' War, the Prussian military acquired a formidable reputation across Europe.[101] Esteemed for their efficiency and success in battle, the Prussian army of Frederick became a model emulated by other European powers, most notably by Russia and France; the latter of which quickly applied the lessons of Frederick's military tactics under the direction of Napoleon Bonaparte upon their erstwhile European neighbors.[102]

Frederick was an influential military theorist whose analysis emerged from his extensive personal battlefield experience and covered issues of strategy, tactics, mobility and logistics.[103] Austrian co-ruler Emperor Joseph II wrote, "When the King of Prussia speaks on problems connected with the art of war, which he has studied intensively and on which he has read every conceivable book, then everything is taut, solid and uncommonly instructive. There are no circumlocutions, he gives factual and historical proof of the assertions he makes, for he is well versed in history."[104]

Historian Robert M. Citino describes Frederick's strategic approach:

- In war ... he usually saw one path to victory, and that was fixing the enemy army in place, maneuvering near or even around it to give himself a favorable position for the attack, and then smashing it with an overwhelming blow from an unexpected direction. He was the most aggressive field commander of the century, perhaps of all time, and one who constantly pushed the limits of the possible.[105]

Historian Dennis Showalter argues: "The King was also more consistently willing than any of his contemporaries to seek decision through offensive operations."[106]

Foresight ranked among the most important attributes when fighting an enemy, according to the Prussian monarch, as the discriminating commander must see everything before it takes place, so "nothing will be new to him."[107] Thus it was flexibility that was often paramount to military success. Donning both the skin of a fox or a lion in battle, as Frederick once remarked, reveals the intellectual dexterity he applied to the art of warfare.

Much of the structure of the more modern German General Staff owed its existence and extensive structure to Frederick, along with the accompanying power of autonomy given to commanders in the field.[108] According to Citino, "When later generations of Prussian-German staff officers looked back to the age of Frederick, they saw a commander who repeatedly, even joyfully, risked everything on a single day's battle – his army, his kingdom, often his very life."[105] As far as Frederick was concerned, there were two major battlefield considerations – speed of march and speed of fire.[109] So confident in the performance of men he selected for command when compared to those of his enemy, Frederick once quipped, "A general considered audacious in another country is only ordinary in [Prussia]; [our general] is able to dare and undertake anything it is possible for men to execute."[110]

Even the later military reputation of Prussia under Bismarck and Moltke rested on the weight of mid-eighteenth century military developments and the territorial expansion of Frederick the Great.[111] Despite his dazzling success as a military commander, Frederick was no fan of protracted warfare, and once wrote, "Our wars should be short and quickly fought… A long war destroys … our [army's] discipline; depopulates the country, and exhausts our resources."[112] Martial adeptness and that thoroughness and discipline so often witnessed on the battlefield was not correspondingly reflected on the domestic front for Frederick.[113] In lieu of his military predilections, Frederick administered his Kingdom justly and ranks among the most "enlightened" monarchs of his era; this, notwithstanding the fact that in many ways, "Frederick the Great represented the embodiment of the art of war".[114] Consequently, Frederick continues to be held in high regard as a military theorist the world over.

Administrative modernization

Frederick helped transform Prussia from a European backwater to an economically strong and politically reformed state. He protected his industries with high tariffs and minimal restrictions on domestic trade. He reformed the judicial system, allowed freedom of speech in press and literature. He abolished most uses of judicial torture, except the flogging of soldiers as punishment for desertion. The death penalty could be carried out only with a warrant signed by the King himself; Frederick only signed a handful of these warrants per year, and then only for murder. He made it possible for men not of noble stock to become judges and senior bureaucrats. William L. Langer finds that "Prussian justice became the most prompt and efficient in Europe".[115] Frederick the Great promoted a more active population policy, which meant more tax revenues, but also soldiers for the army. New agricultural land was reclaimed at the Oder.

In January 1750, Johann Philipp Graumann was appointed as Frederick's confidential adviser on finance, military affairs, and royal possessions, as well as the Director-General of all mint facilities.[116] Graumann had two main tasks: first, he was to secure the availability of coin silver for the Prussian monetary system; second, he was to eliminate the currency chaos of the Austrian War of Succession and rationalize the Prussian coinage. Prussia adopted a Prussian thaler containing 1⁄14 of a Cologne mark of silver, rather than 1⁄12 (in use since 1690), probably in the expectation that this realistic coin foot would prevail throughout the empire. In addition, he wanted to compete with the French Louis d'or, which was used all over Germany and the Dutch currency which was used for trading in the Baltic states. Graumann announced that he would be able to achieve high coin seignorage for the state and that Berlin would become the largest exchange center in Central and Northern Europe.

Frederick reorganized the Prussian Academy of Sciences and attracted many scientists to Berlin. Around 1751 he founded the Emden Company to promote trade with China. He introduced Friedrich d'or, a lottery, a fire insurance and to stabilize the economy a giro discount and credit bank.[117] One of Frederick's achievements after the Seven Years' War included the control of grain prices, whereby government storehouses would enable the civilian population to survive in needy regions, where the harvest was poor.[118] He commissioned Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky to promote the trade and — to take on the competition with France — put a silk factory where soon 1,500 people found employment. Frederick the Great followed his recommendations in the field of toll levies and import restrictions. When Gotzkowsky asked for a deferral during the Amsterdam banking crisis of 1763, Frederick took over his porcelain factory, now known as KPM.[119]

Frederick modernized the Prussian bureaucracy and civil service and promoted religious tolerance throughout his realm to attract more settlers in East Prussia. With the help of French experts, he organized a system of indirect taxation, which would provide the state with more revenue than direct taxation; the French officials who would have to lease the tax failed.[120] In 1781, Frederick made coffee a royal monopoly and employed disabled soldiers to spy on citizens sniffing in search of illegally roasted coffee, much to the annoyance of the general population.[121]

Religious policies

Frederick was a religious skeptic, in contrast to his devoutly Calvinist father.[lower-alpha 4] He tolerated all faiths in his realm, but Protestantism remained the favored religion, and Catholics were not chosen for higher state positions.[122] Frederick was known to be more tolerant of Jews and Catholics than many neighboring German states.

Frederick wanted development throughout the country, adapted to the needs of each region. He was interested in attracting a diversity of skills to his country, whether from Jesuit teachers, Huguenot citizens, or Jewish merchants and bankers. He retained Jesuits as teachers in Silesia, Warmia, and the Netze District after their suppression by Pope Clement XIV. Like Catherine II of Russia, Frederick recognised the educational activities of the Jesuits as an asset for the nation.[123] He also accepted countless Protestant weavers from Bohemia, who were fleeing from the devoutly Catholic rule of Maria Theresa, granting them freedom from taxes and military service.[124] The best known Jews in Frederick's favor were the Rothschilds of Frankfurt, who eventually attained the status of court bankers in Hesse-Kassel in 1795.[125] As an example of Frederick's practical-minded but not fully unprejudiced tolerance, Frederick wrote in his Testament politique:

We have too many Jews in the towns. They are needed on the Polish border because in these areas Hebrews alone perform trade. As soon as you get away from the frontier, the Jews become a disadvantage, they form cliques, they deal in contraband and get up to all manner of rascally tricks which are detrimental to Christian burghers and merchants. I have never persecuted anyone from this or any other sect; I think, however, it would be prudent to pay attention, so that their numbers do not increase.[126]

Jews on the Polish border were therefore encouraged to perform all the trade they could and received the same protection and support from the king as any other Prussian citizen.[127] The success in integrating the Jews into those areas of society where Frederick encouraged them can be seen by the role played in the 19th century by Gerson von Bleichröder in financing Bismarck's efforts to reunite Germany.[128]

In territories he conquered from Poland, Frederick persecuted Polish Roman Catholic churches by confiscating goods and property, exercising strict control of churches, and interfering in church administration[129]

As Frederick made more wasteland arable, Prussia looked for new colonists to settle the land. To encourage immigration, he repeatedly emphasized that nationality and religion were of no concern to him. This policy allowed Prussia's population to recover very quickly from its considerable losses during Frederick's three wars.[66]

Like many leading figures in the Age of Enlightenment, Frederick was a Freemason, and his membership legitimized the group and protected it against charges of subversion.[130][131]

Environment and agriculture

Frederick the Great was keenly interested in land use, especially draining swamps and opening new farmland for colonizers who would increase the kingdom's food supply. He called it "peopling Prussia" (Peuplierungspolitik). About a thousand new villages were founded in his reign that attracted 300,000 immigrants from outside Prussia. He told Voltaire, "Whoever improves the soil, cultivates land lying waste and drains swamps, is making conquests from barbarism".[132] Using improved technology enabled him to create new farmland through a massive drainage program in the country's Oderbruch marsh-land. This program created roughly 60,000 hectares (150,000 acres) of new farmland, but also eliminated vast swaths of natural habitat, destroyed the region's biodiversity, and displaced numerous native plant and animal communities. Frederick saw this project as the "taming" and "conquering" of nature, which, in its wild form, he regarded as "useless" and "barbarous"—an attitude that reflected his enlightenment-era, rationalist sensibilities.[133] He presided over the construction of canals for bringing crops to market, and introduced new crops, especially the potato and the turnip, to the country. For this, he was sometimes called Der Kartoffelkönig (the Potato King).[134]

Frederick's interest in land reclamation may have resulted from his upbringing. As a child, his father, Frederick William I, made young Frederick work in the region's provinces, teaching the boy about the area's agriculture and geography. This created an interest in cultivation and development that powered the boy as he became ruler.[135]

The king founded the first veterinary school in Germany. Unusual for his time and aristocratic background, he criticized hunting as cruel, rough and uneducated. When someone once asked Frederick why he did not wear spurs when riding his horse, he replied, "Try sticking a fork into your naked stomach, and you will soon see why."[4] He loved dogs and his horse and wanted to be buried with his greyhounds. In 1752 he wrote to his sister Wilhelmine that people indifferent to loyal animals would not be devoted to their human comrades either, and that it was better to be too sensitive than too harsh. He was also close to nature and issued decrees to protect plants.[136]

Arts and education

Frederick was a patron of music as well as a gifted musician who played the transverse flute.[137][138] He composed more than 100 sonatas for the flute as well as four symphonies. The Hohenfriedberger Marsch, a military march, was supposedly written by Frederick to commemorate his victory in the Battle of Hohenfriedberg during the Second Silesian War. His court musicians included C. P. E. Bach, Johann Joachim Quantz, Carl Heinrich Graun and Franz Benda. A meeting with Johann Sebastian Bach in 1747 in Potsdam led to Bach's writing The Musical Offering.[lower-alpha 5]

Frederick aspired to be a Philosopher king; he joined the Freemasons in 1738 and corresponded with key French Enlightenment figures. These included Voltaire, whose friend the Marquis d'Argens, was appointed Royal Chamberlain in 1742, then Director of the Prussian Academy of Arts and Berlin State Opera.[139]

While using German as a working language in the army and with his administration, Frederick read and wrote his literary works in French and also generally used that language with his closest relatives or friends. Though he had a good command of this language, his writing style was flawed; he had troubles with its orthography and always had to rely on French proofreaders.

Frederick disliked the German language and literature, explaining that German authors "pile parenthesis upon parenthesis, and often you find only at the end of an entire page the verb on which depends the meaning of the whole sentence".[140] He discarded many Baroque era authors as uncreative pedants and especially despised German theatre. Also, he was cool toward the revival of German culture in the later part of his reign, as he was unimpressed by the authors of the "Sturm und Drang" movement and remained of essentially classical taste. His main inspirations were ancient philosophers and poets as well as French authors of the 17th century. However, interest in foreign cultures was by no means an exception in Germany at that time. The Habsburg court at Vienna was open to influences from Italy, Spain and France. Many German rulers sought to emulate the success of Louis XIV of France and adopted French tastes and manners, though often adapted to the German cultural context. In the case of Frederick II, it might also have been a reaction to the austerity of the family environment created by his father, who had a deep aversion for France and was not interested in the cultural development of his state.

On the other hand, while still considering the German culture of his time to be inferior to that of France or Italy, he did try to foster its development. He thought that it had been hindered by the devastating wars of the 17th century (the Thirty Years' War, the Ottoman wars, the invasions of Louis XIV) but that with some time and effort, it could equal or even surpass its rivals.[141] In his view, this would require a complete codification of the German language with the help of official academies, the emergence of talented classical German authors and extensive patronage of the arts from Germanic rulers, a project of a century or more.[141] Frederick's love of French culture was not without limits either. He disapproved of the luxury and extravagance of the French royal court, and he ridiculed German princes (especially Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland) who imitated French sumptuousness.[142] His own court remained quite Spartan, frugal and small, restricted to a limited circle of close friends- a layout similar to his father's court, though Frederick and his friends were far more cultured than Frederick William. Also, Frederick the Great was dismissive of the radical philosophy of later French thinkers such as Rousseau (though he in fact sheltered Rousseau from persecution for a number of years), and grew to believe that the French cultural golden age was drawing to a close.

Despite his distaste for German, Frederick did sponsor the Königliche Deutsche Gesellschaft (Royal German Society), founded in Königsberg in 1741, the aim of which was to promote and develop the German language. He allowed the association to be titled "royal" and have its seat at the Königsberg Castle. However, he does not seem to have taken much interest in the work of the society. Frederick also promoted the use of German instead of Latin in the field of law, though mainly for practical reasons.[143] Moreover, it was under his reign that Berlin became an important center of German enlightenment.

The king's criticism led many German writers to attempt to impress Frederick with their writings in the German language and thus prove its worthiness. Many statesmen, including Baron vom und zum Stein, were also inspired by Frederick's statesmanship. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe gave his opinion of Frederick during a visit to Strasbourg (Strassburg) by writing:

Well, we had not much to say in favour of the constitution of the Reich; we admitted that it consisted entirely of lawful misuses, but it rose therefore the higher over the present French constitution which is operating in a maze of unlawful misuses, whose government displays its energies in the wrong places and therefore has to face the challenge that a thorough change in the state of affairs is widely prophesied. In contrast when we looked towards the north, from there shone Frederick, the Pole Star, around whom Germany, Europe, even the world seemed to turn ...[144]

Architecture

Frederick had many famous buildings constructed in his capital Berlin, most of which still stand today, such as the Berlin State Opera, the Royal Library (today the State Library Berlin), St. Hedwig's Cathedral, and Prince Henry's Palace (now the site of Humboldt University). However, the king preferred spending his time in his summer residence at Potsdam, where he built the palace of Sanssouci, the most important work of Northern German rococo. Sanssouci (French for "carefree" or "without worry"), was a refuge for Frederick. "Frederician Rococo" developed under Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff.

Picture gallery at Sanssouci

As a great patron of the arts, Frederick was a collector of paintings and ancient sculptures; his favorite artist was Jean-Antoine Watteau. The picture gallery at Sanssouci "represents a unique synthesis of the arts in which architecture, painting, sculpture and the decorative arts enter into dialogue with each other, forming a compendium of the arts."[145] The gilded stucco decorations of the ceilings were created by Johann Michael Merck (1714–1784) and Carl Joseph Sartori (1709–1770). Both the wall paneling of the galleries and the diamond shapes of the floor consist of white and yellow marble. Paintings by different schools were displayed strictly separately: 17th-century Flemish and Dutch paintings filled the western wing and the gallery's central building, while Italian paintings from the High Renaissance and Baroque were exhibited in the eastern wing. Sculptures were arranged symmetrically or in rows in relation to the architecture.[lower-alpha 6]

Berlin Academy

Aarsleff notes that before Frederick came to the throne in 1740, the Prussian Academy of Sciences (Berlin Academy) was overshadowed by similar bodies in London and Paris. During the reign of Frederick's father, the Academy had been closed down as an economy measure, but Frederick promptly re-opened it when he took the throne in 1740. Frederick made French the official language and speculative philosophy the most important topic of study. The membership was strong in mathematics and philosophy and included Immanuel Kant, Jean D'Alembert, Pierre Louis de Maupertuis, and Étienne de Condillac. However the Academy was in a crisis for two decades at mid-century, due to scandals and internal rivalries such as the debates between Newtonianism and Leibnizian views, and the personality conflict between Voltaire and Maupertuis. At a higher level Maupertuis, the director 1746–59 and a monarchist, argued that the action of individuals was shaped by the character of the institution that contained them, and they worked for the glory of the state. By contrast d' Alembert took a republican rather than monarchical approach and emphasized the international Republic of Letters as the vehicle for scientific advance.[146] By 1789, however, the academy had gained an international repute while making major contributions to German culture and thought. Frederick invited Joseph-Louis Lagrange to succeed Leonhard Euler at the Berlin Academy; both were world-class mathematicians. Other intellectuals attracted to the philosopher's kingdom were Francesco Algarotti, d'Argens, and Julien Offray de La Mettrie. Immanuel Kant published religious writings in Berlin which would have been censored elsewhere in Europe.[147]

Sexual orientation

Most modern biographers agree that Frederick was primarily homosexual, and that his sexual orientation was central to his life.[148][149][150][151][152] After a dispiriting defeat on the battlefield, Frederick wrote: "Fortune has it in for me; she is a woman, and I am not that way inclined."[153]

At age 16, Frederick seems to have embarked upon a youthful affair with Peter Karl Christoph von Keith, a 17-year-old page of his father. Rumors of the liaison spread in the court and the "intimacy" between the two boys provoked the condemnation of even his elder and favorite sister, Wilhelmine,[14] who wrote, "Though I had noticed that he was on more familiar terms with this page than was proper in his position, I did not know how intimate the friendship was."[13] Rumors finally reached King Frederick William, who cultivated an ideal of ultramasculinity in his court, and derided his son's "effeminate" tendencies. As a result, Keith was dismissed from his service to the king and sent away to a regiment by the Dutch border, while Frederick was sent to Wusterhausen in order to "repent of his sin."[14] Frederick's relationship with Hans Hermann von Katte was also believed by King Frederick William to be romantic, a suspicion which enraged him, and he had von Katte put to death.[154]

Frederick's physician Johann Georg Ritter von Zimmermann claimed that Frederick had suffered a minor deformity during an operation to cure gonorrhea in 1733, and convinced himself that he was impotent, but pretended to be homosexual in order to appear that he was still virile and capable of intercourse, albeit with men. This story is doubted by Wolfgang Burgdorf, who is of the opinion that "Frederick had a physical disgust of women" and therefore "was unable to sleep with them."[150][156]

In 1739, Frederick met the Venetian philosopher Francesco Algarotti, and they were both infatuated.[157][158] Frederick planned to make him a count. Challenged by Algarotti that northern Europeans lacked passion, Frederick penned for him an erotic poem, La Jouissance, which imagined Algarotti in the throes of sexual intercourse with another partner, a female named Chloris.[159] Not all Frederick scholars have interpreted the poem in such a way; some have read it as describing a tryst between two men.[160] For Giles MacDonogh, Algarotti's partner in the poem is Frederick himself; MacDonogh, whose 1999 biography of Frederick is ambiguous as to the king's sexual orientation, was convinced by the poem that Frederick was gay.[160] It is known that other homoerotic poems were written by the king, but none, including La Jouissance, unequivocally exposes the king as being involved in such affairs.[160]

In 1733, Frederick was forced to marry Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Bevern, with whom he had no children. He immediately separated from his wife when his father died seven years later. He would later only pay her formal visits once a year.[161] These were on her birthday and were some of the rare occasions when Frederick did not wear military uniform.[162]

William Hogarth's painting The Toilette features a flautist (who stands next to a painting of Zeus, as an eagle, abducting Ganymede), which may be a satirical depiction of Frederick – thereby publicly outing him as a homosexual as early as 1744.[163][164] In the New Palace, his greatest place of residence, Frederick kept the fresco Ganymede Is Introduced to Olympus by Charles Vanloo: "the largest fresco in the largest room in his largest palace", in the words of a biographer.[165]

Frederick certainly spent much of his time at Sanssouci, his favourite residence in Potsdam, in a circle that was exclusively male, though a number of his entourage were married.[166][167] The palace gardens include a Temple of Friendship (built as a memorial to Wilhelmine), which celebrate the homoerotic attachments of Greek Antiquity, and which is decorated with portraits of Orestes and Pylades, amongst others.[168] At Sanssouci, Frederick entertained his most privileged guests, especially the French philosopher Voltaire, whom he asked in 1750 to come to live with him. Their literary correspondence and friendship, which spanned almost 50 years, was marked by mutual intellectual fascination, and began as a flirtation.[169][170] However, in person Frederick found Voltaire difficult to live with, and was often annoyed by Voltaire's many quarrels with his other friends. Voltaire's angry attack on Maupertuis, the President of Frederick's academy, in the form of Le Diatribe du Docteur Akakia provoked Frederick to burn the pamphlet publicly and put Voltaire under house arrest, after which Voltaire left Prussia.

In the 1750s Voltaire began writing his Mémoires.[171] The manuscript was stolen and a pirate copy was published in Amsterdam in 1784 as The Private Life of the King of Prussia.[172] In it, Voltaire explicitly detailed Frederick's homosexuality and the circle surrounding him. The revelations and language were strikingly similar to those detailed in a scurrilous pamphlet published in French, in London in 1752.[173] After a temporary cooling of Frederick and Voltaire's friendship, they resumed their correspondence, and aired mutual recriminations, to end as friends once more.[174] A further intimate friendship was with his first valet Michael Gabriel Fredersdorf who, Frederick confided to his diary, had "a very pretty face": Fredersdorf was provided with an estate, and acted as unofficial prime minister.[175]

Later years and death

In 1785, Frederick signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States of America, recognising the independence of the new nation. The agreement included a novel clause, whereby the two leaders of the executive branches of either country guaranteed a special and humane detention for prisoners of war.[176]

Near the end of his life, Frederick grew increasingly solitary. His circle of close friends at Sanssouci gradually died off with few replacements, and Frederick became increasingly critical and arbitrary, to the frustration of the civil service and officer corps. The populace of Berlin always cheered the king when he returned to the city from provincial tours or military reviews, but Frederick evinced little pleasure from his popularity with the common people, preferring instead the company of his pet Italian greyhounds,[177] whom he referred to as his "marquises de Pompadour" as a jibe at the French royal mistress.[178] Even in his late 60s and early 70s when he was increasingly crippled by asthma, gout and other ailments, he rose before dawn, drank six to eight cups of coffee a day, "laced with mustard and peppercorns", and attended to state business with characteristic tenacity.[179]

On the morning of 17 August 1786, Frederick died in an armchair in his study at Sanssouci, aged 74. He left instructions that he should be buried next to his greyhounds on the vineyard terrace, on the side of the corps de logis of Sanssouci. His nephew and successor Frederick William II instead ordered the body to be entombed next to his father in the Potsdam Garrison Church. Near the end of World War II, Hitler ordered Frederick's coffin, along with those of his father Frederick William I, World War I Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, and Hindenburg's wife Gertrud, to be hidden in a salt mine as protection from destruction. The United States Army relocated the remains to Marburg in 1946; in 1953, the coffins of Frederick and his father were moved to Burg Hohenzollern.[180]

On the 205th anniversary of his death, on 17 August 1991, Frederick's casket lay in state in the court of honor at Sanssouci, covered by a Prussian flag and escorted by a Bundeswehr guard of honor. After nightfall, Frederick's body was finally laid to rest in the terrace of the vineyard of Sanssouci—in the still existing crypt he had built there—without pomp, in accordance with his will.[181]

Historiography and memory

In German memory, Frederick became a great national hero in the 19th century and many Germans said he was the greatest monarch in modern history.[182] German historians often made him the romantic model of a glorified warrior, praising his leadership, administrative efficiency, devotion to duty and success in building up Prussia to a leading role in Europe.

Historian Leopold von Ranke was unstinting in his praise of Frederick's "heroic life, inspired by great ideas, filled with feats of arms ... immortalized by the raising of the Prussian state to the rank of a power".[5] Johann Gustav Droysen was even more favorable. Nationalist historian Heinrich von Treitschke presented Frederick as the greatest German in centuries. Onno Klopp was one of the few German historians of the 19th century who denigrated and ridiculed Frederick. The novelist Thomas Mann in 1914 also attacked Frederick, arguing—like Empress Maria Theresa—that he was a wicked man who robbed Austria of Silesia, precipitating the alliance against him. Nevertheless, with Germany humiliated after World War I, Frederick's popularity as a heroic figure remained high in Germany. Thomas Carlyle's History of Frederick the Great (8 vol. 1858–1865) emphasized the power of one great "hero", in this case Frederick, to shape history.[183]

.jpg)

The anti-revolutionary French Jesuit Augustin Barruel, author of an influential Conspiracy theory set out in his 1797 book Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism (French: Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire du Jacobinisme), accused King Frederick of taking part in a plot which led to the outbreak of the French Revolution and having been the secret "protector and adviser" of fellow-conspirators Voltaire, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, and Denis Diderot, who all sought "to destroy Christianity" and foment "rebellion against Kings and Monarchs".[184]

In 1933–1945, the Nazis glorified Frederick as a precursor to Adolf Hitler and presented Frederick as holding out hope that another miracle would again save Germany at the last moment.[185] Nevertheless, the nationalist (but anti-Nazi) historian Gerhard Ritter condemned Frederick's brutal seizure in the first partition of Poland, although he praised the results as beneficial to the Polish people.[186][187] Ritter's biography of Frederick, published in 1936, was designed as a challenge to Nazi claims that there was a continuity between Frederick and Hitler. Dorpalen says: "The book was indeed a very courageous indictment of Hitler's irrationalism and recklessness, his ideological fanaticism and insatiable lust for power".[188]

Throughout World War II, Hitler often compared himself to Frederick the Great.[189] British-American historian Gordon A. Craig relates that to help legitimize Nazi rule Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels commissioned artists to render fanciful images of Frederick, Bismarck, and Hitler together to postulate a historical continuum between them.[190] Hitler kept an oil painting of Anton Graff's portrait of Frederick (see top of page) with him to the end in the Führerbunker in Berlin.[6]

Frederick's reputation was sharply downgraded after 1945 in both East and West Germany.[7] His diminished legacy in Germany was due in part to the Nazis' fascination with him, to say nothing of his supposed connection with Prussian militarism.[191] Nonetheless, nowadays Frederick is generally held in high regard, especially for his statesmanship—and for his enlightened reforms that positively changed not only Germany, but European society in general, allowing German intellectuals to assert that the revolutions in both France and America were to some extent "belated" attempts to "catch up with Prussia".[192]

In the 21st century, his reputation as a warrior remains strong among military historians.[193][194] Historians in general continue to debate the issue of continuity versus innovation. How much of the king's achievement was based on developments already under way, and how much can be attributed to his initiative? How closely linked was he to the Enlightenment? Is the category of "enlightened absolutism" still useful for the scholar?[195][196]

Frederick in popular culture

Places

King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, is named after the King of Prussia Inn, itself named in honour of Frederick.[197]

German films

The Great King (German: Der Große König) is a 1942 German drama film directed by Veit Harlan and starring Otto Gebühr.[198] It depicts the life of Frederick the Great. It received the rare "Film of the Nation" distinction.[199] Otto Gebühr also played the King in many other films.

- Films with Otto Gebühr as Frederick the Great

- 1920: The Dancer Barberina – director: Carl Boese

- 1921–1923: Fridericus Rex – director: Arzén von Cserépy

- Teil 1 – Sturm und Drang

- Teil 2 – Vater und Sohn

- Teil 3 – Sanssouci

- Teil 4 – Schicksalswende

- 1926: The Mill at Sanssouci – director: Siegfried Philippi

- 1928: The Old Fritz – 1. Teil Friede – director: Gerhard Lamprecht

- 1928: Der alte Fritz – 2. Teil Ausklang – director: Gerhard Lamprecht

- 1930: The Flute Concert of Sanssouci – director: Gustav Ucicky

- 1932: The Dancer of Sanssouci – director: Friedrich Zelnik

- 1933: The Hymn of Leuthen – director: Carl Froelich

- 1936. Heiteres und Ernstes um den großen König – director: Phil Jutzi

- 1936: Fridericus – director: Johannes Meyer

- 1937: Das schöne Fräulein Schragg – director: Hans Deppe

- 1942: The Great King – director: Veit Harlan

In the 2004 German film Der Untergang (Downfall), Adolf Hitler is shown sitting in a dark room forlornly gazing at a painting of Frederick. This is based on an incident witnessed by Rochus Misch.[200]

The 2012 German made-for-television film Friedrich – ein deutscher König (Frederick – a German King) starred the actresses Katharina Thalbach and her daughter Anna Thalbach in the title roles as the old and young king respectively.

Other

Frederick has been included in the Civilization computer game series, the computer games Age of Empires III, Empire Earth II, Empire: Total War, and the board games Friedrich and Soldier Kings.[201]

He is recorded as the first to claim that "dog is man's best friend", as he referred to one of his Italian greyhounds as his best friend.[202]

In 1986, he was made the subject of a painting by pop-art icon Andy Warhol, entitled "Friederich the Great," a print of which may be viewed by the public on the 10th floor of the Holiday Inn in downtown New Orleans.[203]

In 2016, Frederick was featured on Epic Rap Battles of History as an opponent of Ivan the Terrible in a rap battle between Alexander the Great and Ivan the Terrible and is portrayed by Lloyd Ahlquist.

In the satirical alternate history story "The Merry German Prince" by Barry Kaufman, the young Frederick and his friend Katte did manage to escape to England. Frederick's furious father disinherited him and had him sentenced to death in absentia. Frederick lived out a bohemian life as an exile shifting between the royal courts in London and Paris, and got some name as a poet, composer and musical performer. The Prussian throne was inherited by Frederick's brother Augustus William, under whom Prussia was decisively defeated in the War of the Austrian Succession, its army crushed and much of its territory taken away - never again to contend seriously for supremacy. As a result, Germany was never unified, remaining a loose collection of principalities, and in the 20th Century there were no World Wars.

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

- 24 January 1712 – 31 May 1740 – His Royal Highness The Crown Prince of Prussia

- 31 May 1740 – 19 February 1772 – His Majesty The King in Prussia.

- 19 February 1772 – 17 August 1786 – His Majesty The King of Prussia.

Honours

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

See also

References

Footnotes

- Frederick was the third and last "King in Prussia"; beginning in 1772 he used the title "King of Prussia".

- For a quick overview of the conflict, see: Marston, Daniel. The Seven Years' War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2001.

- Compare: [66]

- However, he remained critical of Christianity. See Letters of Voltaire and Frederick the Great (New York: Brentano's, 1927), trans. Richard Aldington, letter 37 from Frederick to Voltaire (June 1738). "Christianity ... is an old metaphysical fiction, stuffed with fables, contradictions and absurdities: it was spawned in the fevered imagination of the Orientals, and then spread to our Europe, where some fanatics espoused it, where some intriguers pretended to be convinced by it and where some imbeciles actually believed it". Attributed in The West and the Rest by Niall Ferguson, Penguin 2011 (Kindle edition).