Ancient Greek medicine

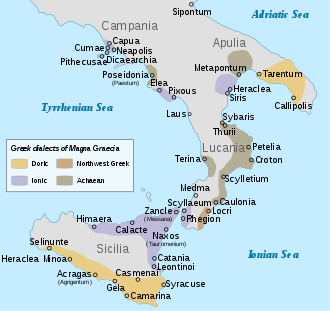

Ancient Greek Medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. Many components were considered in ancient Greek medicine, intertwining the spiritual with the physical. Specifically, the ancient Greeks believed health was affected by the humors, geographic location, social class, diet, trauma, beliefs, and mindset. Early on the ancient Greeks believed that illnesses were "divine punishments" and that healing was a "gift from the Gods".[1] As trials continued wherein theories were tested against symptoms and results, the pure spiritual beliefs regarding "punishments" and "gifts" were replaced with a foundation based in the physical, i.e., cause and effect.[1]

Humorism (or the four humors) refers to blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. It was also theorized that sex played a role in medicine because some diseases and treatments were different for females than for males. Moreover, geographic location and social class affected the living conditions of the people and might subject them to different environmental issues such as mosquitoes, rats, and availability of clean drinking water. Diet was thought to be an issue as well and might be affected by a lack of access to adequate nourishment. Trauma, such as that suffered by gladiators, from dog bites or other injuries, played a role in theories relating to understanding anatomy and infections. Additionally, there was significant focus on the beliefs and mindset of the patient in the diagnosis and treatment theories. It was recognized that the mind played a role in healing, or that it might also be the sole basis for the illness.[2]

Ancient Greek medicine began to revolve around the theory of humors. The humoral theory states that good health comes from a perfect balance of the four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Consequently, poor health resulted from improper balance of the four humors . Hippocrates, known as the "Father of Modern Medicine", established a medical school at Cos and is the most important figure in ancient Greek medicine.[3] Hippocrates and his students documented numerous illnesses in the Hippocratic Corpus, and developed the Hippocratic Oath for physicians, which is still in use today. The contributions to ancient Greek medicine of Hippocrates, Socrates and others had a lasting influence on Islamic medicine and medieval European medicine until many of their findings eventually became obsolete in the 14th century.

The earliest known Greek medical school opened in Cnidus in 700 BC. Alcmaeon, author of the first anatomical compilation, worked at this school, and it was here that the practice of observing patients was established. Despite their known respect for Egyptian medicine, attempts to discern any particular influence on Greek practice at this early time have not been dramatically successful because of the lack of sources and the challenge of understanding ancient medical terminology. It is clear, however, that the Greeks imported Egyptian substances into their pharmacopoeia, and the influence became more pronounced after the establishment of a school of Greek medicine in Alexandria.[4]

Asclepieia

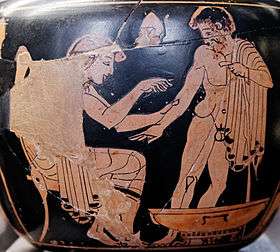

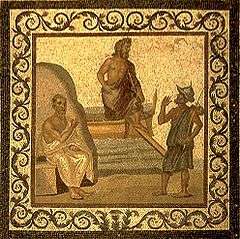

Asclepius was espoused as the first physician, and myth placed him as the son of Apollo. Temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia (Greek: Ἀσκληπιεῖα; sing. Ἀσκληπιεῖον Asclepieion), functioned as centers of medical advice, prognosis, and healing.[5] At these shrines, patients would enter a dream-like state of induced sleep known as "enkoimesis" (Greek: ἐγκοίμησις) not unlike anesthesia, in which they either received guidance from the deity in a dream or were cured by surgery.[6] Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing.[5] The Temple of Asclepius in Pergamum had a spring that flowed down into an underground room in the Temple. People would come to drink the waters and to bathe in them because they were believed to have medicinal properties. Mud baths and hot teas such as chamomile were used to calm them or peppermint tea to soothe their headaches, which is still a home remedy used by many today. The patients were encouraged to sleep in the facilities too. Their dreams were interpreted by the doctors and their symptoms were then reviewed. Dogs would occasionally be brought in to lick open wounds for assistance in their healing. In the Asclepieion of Epidaurus, three large marble boards dated to 350 BC preserve the names, case histories, complaints, and cures of about 70 patients who came to the temple with a problem and shed it there. Some of the surgical cures listed, such as the opening of an abdominal abscess or the removal of traumatic foreign material, are realistic enough to have taken place, but with the patient in a state of enkoimesis induced with the help of soporific substances such as opium.[6]

The Rod of Asclepius is a universal symbol for medicine to this day. However, it is frequently confused with Caduceus, which was a staff wielded by the god Hermes. The Rod of Asclepius embodies one snake with no wings whereas Caduceus is represented by two snakes and a pair of wings depicting the swiftness of Hermes.

Ancient Greek physicians

Ancient Greek physicians regarded disease as being of supernatural origin, brought about from the dissatisfaction of the gods or from demonic possession.[7] The fault of the ailment was placed on the patient and the role of the physician was to conciliate with the gods or exorcise the demon with prayers, spells, and sacrifices.

The Hippocratic Corpus and Humorism

.jpg)

The Hippocratic Corpus opposes ancient beliefs, offering biologically based approaches to disease instead of magical intervention. The Hippocratic Corpus is a collection of about seventy early medical works from ancient Greece that are associated with Hippocrates and his students. Although once thought to have been written by Hippocrates himself, many scholars today believe that these texts were written by a series of authors over several decades.[8] The Corpus contains the treatise, the Sacred Disease, which argues that if all diseases were derived from supernatural sources, biological medicines would not work. The establishment of the humoral theory of medicine focused on the balance between blood, yellow and black bile, and phlegm in the human body. Being too hot, cold, dry or wet disturbed the balance between the humors, resulting in disease and illness. Gods and demons were not believed to punish the patient, but attributed to bad air (miasma theory). Physicians who practiced humoral medicine focused on reestablishing balance between the humors. The shift from supernatural disease to biological disease did not completely abolish Greek religion, but offered a new method of how physicians interacted with patients.

Ancient Greek physicians who followed humorism emphasized the importance of environment. Physicians believed patients would be subjected to various diseases based on the environment they resided. The local water supply and the direction the wind blew influenced the health of the local populace. Patients played an important role in their treatment. Stated in the treatise "Aphorisms", "[i]t is not enough for the physician to do what is necessary, but the patient and the attendant must do their part as well".[9] Patient compliance was rooted in their respect for the physician. According to the treatise "Prognostic", a physician was able to increase their reputation and respect through "prognosis", knowing the outcome of the disease. Physicians had an active role in the lives of patients, taking into consideration their residence. Distinguishing between fatal diseases and recoverable disease was important for patient trust and respect, positively influencing patient compliance.

With the growth of patient compliance in Greek medicine, consent became an important factor between the doctor and patient relationship. Presented with all the information concerning the patient's health, the patient makes the decision to accept treatment. Physician and patient responsibility is mentioned in the treatise "Epidemics", where it states, "there are three factors in the practice of medicine: the disease, the patient and the physician. The physician is the servant of science, and the patient must do what he can to fight the disease with the assistance of the physician".[10]

Aristotle's influence on Greek perception

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle was the most influential scholar of the living world from antiquity. Aristotle's biological writings demonstrate great concern for empiricism, biological causation, and the diversity of life.[11] Aristotle did not experiment, however, holding that items display their real natures in their own environments, rather than controlled artificial ones. While in modern-day physics and chemistry this assumption has been found unhelpful, in zoology and ethology it remains the dominant practice, and Aristotle's work "retains real interest".[12] He made countless observations of nature, especially the habits and attributes of plants and animals in the world around him, which he devoted considerable attention to categorizing. In all, Aristotle classified 540 animal species, and dissected at least 50.

Aristotle believed that formal causes guided all natural processes.[13] Such a teleological view gave Aristotle cause to justify his observed data as an expression of formal design; for example suggesting that Nature, giving no animal both horns and tusks, was staving off vanity, and generally giving creatures faculties only to such a degree as they are necessary. In a similar fashion, Aristotle believed that creatures were arranged in a graded scale of perfection rising from plants on up to man—the scala naturae or Great Chain of Being.[14]

He held that the level of a creature's perfection was reflected in its form, but not foreordained by that form. Yet another aspect of his biology divided souls into three groups: a vegetative soul, responsible for reproduction and growth; a sensitive soul, responsible for mobility and sensation; and a rational soul, capable of thought and reflection. He attributed only the first to plants, the first two to animals, and all three to humans.[15] Aristotle, in contrast to earlier philosophers, and like the Egyptians, placed the rational soul in the heart, rather than the brain.[16] Notable is Aristotle's division of sensation and thought, which generally went against previous philosophers, with the exception of Alcmaeon.[17]

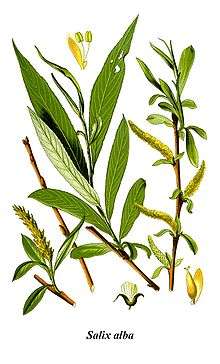

Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany—the History of Plants—which survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to botany, even into the Middle Ages. Many of Theophrastus' names survive into modern times, such as carpos for fruit, and pericarpium for seed vessel. Rather than focus on formal causes, as Aristotle did, Theophrastus suggested a mechanistic scheme, drawing analogies between natural and artificial processes, and relying on Aristotle's concept of the efficient cause. Theophrastus also recognized the role of sex in the reproduction of some higher plants, though this last discovery was lost in later ages.[18] The biological/teleological ideas of Aristotle and Theophrastus, as well as their emphasis on a series of axioms rather than on empirical observation, cannot be easily separated from their consequent impact on Western medicine.

Herophilus and Erasistratus

After Theophrastus (d. 286 BC), the extent of original work produced was diminished. Though interest in Aristotle's ideas survived, they were generally taken unquestioningly.[19] It is not until the age of Alexandria under the Ptolemies that advances in biology can be again found. The first medical teacher at Alexandria was Herophilus of Chalcedon, who differed from Aristotle, placing intelligence in the brain, and connected the nervous system to motion and sensation. Herophilus also distinguished between veins and arteries, noting that the latter had a pulse while the former do not. He did this using an experiment involving cutting certain veins and arteries in a pig's neck until the squealing stopped.[20] In the same vein, he developed a diagnostic technique which relied upon distinguishing different types of pulse.[21] He, and his contemporary, Erasistratus of Chios, researched the role of veins and nerves, mapping their courses across the body.

Erasistratus connected the increased complexity of the surface of the human brain compared to other animals to its superior intelligence. He sometimes employed experiments to further his research, at one time repeatedly weighing a caged bird and noting its weight loss between feeding times. Following his teacher's researches into pneumatics, he claimed that the human system of blood vessels was controlled by vacuums, drawing blood across the body. In Erasistratus' physiology, air enters the body, is then drawn by the lungs into the heart, where it is transformed into vital spirit, and is then pumped by the arteries throughout the body. Some of this vital spirit reaches the brain, where it is transformed into animal spirit, which is then distributed by the nerves.[22] Herophilus and Erasistratus performed their experiments upon criminals given to them by their Ptolemaic kings. They dissected these criminals alive, and "while they were still breathing they observed parts which nature had formerly concealed, and examined their position, colour, shape, size, arrangement, hardness, softness, smoothness, connection."[23]

Though a few ancient atomists such as Lucretius challenged the teleological viewpoint of Aristotelian ideas about life, teleology (and after the rise of Christianity, natural theology) would remain central to biological thought essentially until the 18th and 19th centuries. In the words of Ernst Mayr, "Nothing of any real consequence in biology after Lucretius and Galen until the Renaissance."[24] Aristotle's ideas of natural history and medicine survived, but they were generally taken unquestioningly.[25]

Galen

Aelius Galenus was a prominent Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire.[26][27][28] Arguably the most accomplished of all medical researchers of antiquity, Galen influenced the development of various scientific disciplines, including anatomy,[29] physiology, pathology,[30] pharmacology,[31] and neurology, as well as philosophy[32] and logic.

The son of Aelius Nicon, a wealthy architect with scholarly interests, Galen received a comprehensive education that prepared him for a successful career as a physician and philosopher. Born in Pergamon (present-day Bergama, Turkey), Galen traveled extensively, exposing himself to a wide variety of medical theories and discoveries before settling in Rome, where he served prominent members of Roman society and eventually was given the position of personal physician to several emperors.

Galen's understanding of anatomy and medicine was principally influenced by the then-current theory of humorism, as advanced by ancient Greek physicians such as Hippocrates. His theories dominated and influenced Western medical science for more than 1,300 years. His anatomical reports, based mainly on dissection of monkeys, especially the Barbary macaque, and pigs, remained uncontested until 1543, when printed descriptions and illustrations of human dissections were published in the seminal work De humani corporis fabrica by Andreas Vesalius[33][34] where Galen's physiological theory was accommodated to these new observations.[35] Galen's theory of the physiology of the circulatory system endured until 1628, when William Harvey published his treatise entitled De motu cordis, in which he established that blood circulates, with the heart acting as a pump.[36][37] Medical students continued to study Galen's writings until well into the 19th century. Galen conducted many nerve ligation experiments that supported the theory, which is still accepted today, that the brain controls all the motions of the muscles by means of the cranial and peripheral nervous systems.[38]

Galen saw himself as both a physician and a philosopher, as he wrote in his treatise entitled That the Best Physician is also a Philosopher.[39][40][41] Galen was very interested in the debate between the rationalist and empiricist medical sects,[42] and his use of direct observation, dissection and vivisection represents a complex middle ground between the extremes of those two viewpoints.[43][44][45]

Dioscorides

The first century AD Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and Roman army surgeon Pedanius Dioscorides authored an encyclopedia of medicinal substances commonly known as De Materia Medica. This work did not delve into medical theory or explanation of pathogenesis, but described the uses and actions of some 600 substances, based on empirical observation. Unlike other works of Classical antiquity, Dioscorides' manuscript was never out of publication; it formed the basis for the Western pharmacopeia through the 19th century, a true testament to the efficacy of the medicines described; moreover, the influence of work on European herbal medicine eclipsed that of the Hippocratic Corpes.[46]

Historical legacy

Through long contact with Greek culture, and their eventual conquest of Greece, the Romans adopted a favorable view of Hippocratic medicine.[47]

This acceptance led to the spread of Greek medical theories throughout the Roman Empire, and thus a large portion of the West. The most influential Roman scholar to continue and expand on the Hippocratic tradition was Galen (d. c. 207). Study of Hippocratic and Galenic texts, however, all but disappeared in the Latin West in the Early Middle Ages, following the collapse of the Western Empire, although the Hippocratic-Galenic tradition of Greek medicine continued to be studied and practiced in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium). After AD 750, Arab, Persian and Andalusi scholars translated Galen's and Dioscorides' works in particular. Thereafter the Hippocratic-Galenic medical tradition was assimilated and eventually expanded, with the most influential Muslim doctor-scholar being Avicenna. Beginning in the late eleventh century, the Hippocratic-Galenic tradition returned to the Latin West with a series of translations of the Classical texts, mainly from Arabic translations but occasionally from the original Greek. In the Renaissance, more translations of Galen and Hippocrates directly from the Greek were made from newly available Byzantine manuscripts.

Galen's influence was so great that even after Western Europeans started making dissections in the thirteenth century, scholars often assimilated findings into the Galenic model that otherwise might have thrown Galen's accuracy into doubt. Over time, however, Classical medical theory came to be superseded by increasing emphasis on scientific experimental methods in the 16th and 17th centuries. Nevertheless, the Hippocratic-Galenic practice of bloodletting was practiced into the 19th century, despite its empirical ineffectiveness and riskiness.

See also

References

- Cartwright, Mark (2013). "Greek Medicine". Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited. UK. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Bendick, Jeanne. "Galen – And the Gateway to Medicine." Ignatius Press, San Francisco, CA, 2002. ISBN 1-883937-75-2.

- Atlas of Anatomy, ed. Giunti Editorial Group, Taj Books LTD 2002, p. 9

- Heinrich von Staden, Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 1-26.

- Risse, G. B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 56

- Askitopoulou, H., Konsolaki, E., Ramoutsaki, I., Anastassaki, E. Surgical cures by sleep induction as the Asclepieion of Epidaurus. The mistory of anesthesia: proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium, by José Carlos Diz, Avelino Franco, Douglas R. Bacon, J. Rupreht, Julián Alvarez. Elsevier Science B.V., International Congress Series 1242(2002), p.11-17.

- Kaba, R.; Sooriakumaran, P. (2007). "The evolution of the doctor-patient relationship". International Journal of Surgery. 5 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.01.005. PMID 17386916.

- Vivian Nutton'Ancient Medicine'(Routledge 2004)

- Chadwick, edited with an introduction by G.E.R. Lloyd; translated [from the Greek] by J.; al.], W.N. Mann ... [et (1983). Hippocratic writings ([New] ed., with additional material, Repr. in Penguin classics. ed.). Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 206. ISBN 0140444513.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Chadwick (1983). Hippocratic Writings. p. 94. ISBN 0140444513.

- Mason, A History of the Sciences pp 41

- Annas, Classical Greek Philosophy pp 247

- Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 84-90, 135; Mason, A History of the Sciences, p 41-44

- Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 201-202; see also: Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being

- Aristotle, De Anima II 3

- Mason, A History of the Sciences pp 45

- Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy Vol. 1 pp. 348

- Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 90-91; Mason, A History of the Sciences, p 46

- Annas, Classical Greek Philosophy pp 252

- Mason, A History of the Sciences pp 56

- Barnes, Hellenistic Philosophy and Science pp 383

- Mason, A History of the Sciences, p 57

- Barnes, Hellenistic Philosophy and Science, pp 383-384

- Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 90-94; quotation from p 91

- Annas, Classical Greek Philosophy, p 252

- "Life, death, and entertainment in the Roman Empire". David Stone Potter, D. J. Mattingly (1999). University of Michigan Press. p. 63. ISBN 0-472-08568-9

- "Galen on bloodletting: a study of the origins, development, and validity of his opinions, with a translation of the three works". Peter Brain, Galen (1986). Cambridge University Press. p.1. ISBN 0-521-32085-2

- Nutton Vivian (1973). "The Chronology of Galen's Early Career". Classical Quarterly. 23 (1): 158–171. doi:10.1017/S0009838800036600. PMID 11624046.

- "Galen on the affected parts. Translation from the Greek text with explanatory notes". Med Hist. 21 (2): 212. 1977. doi:10.1017/s0025727300037935. PMC 1081972.

- Arthur John Brock (translator), Introduction. Galen. On the Natural Faculties. Edinburgh 1916

- Galen on pharmacology

- Galen on the brain

- Andreas Vesalius (1543). De humani corporis fabrica, Libri VII (in Latin). Basel, Switzerland: Johannes Oporinus. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- O'Malley, C., Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514–1564, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Siraisi, Nancy G., (1991) Girolamo Cardano and the Art of Medical Narrative, Journal of the History of Ideas. pp. 587–88.

- William Harvey (1628). Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (in Latin). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Sumptibus Guilielmi Fitzeri. p. 72. ISBN 0-398-00793-4. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- Furley, D, and J. Wilkie, 1984, Galen On Respiration and the Arteries, Princeton University Press, and Bylebyl, J (ed), 1979, William Harvey and His Age, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

- Frampton, M., 2008, Embodiments of Will: Anatomical and Physiological Theories of Voluntary Animal Motion from Greek Antiquity to the Latin Middle Ages, 400 B.C.–A.D. 1300, Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag. pp. 180 – 323

- Claudii Galeni Pergameni (1992). Odysseas Hatzopoulos (ed.). "That the best physician is also a philosopher" with a Modern Greek Translation. Athens, Greece: Odysseas Hatzopoulos & Company: Kaktos Editions.

- Theodore J. Drizis (Fall 2008). "Medical ethics in a writing of Galen". Acta Med Hist Adriat. 6 (2): 333–336. PMID 20102254.

- Brian, P., 1977, "Galen on the ideal of the physician", South Africa Medical Journal, 52: 936–938 pdf

- Frede, M. and R. Walzer, 1985, Three Treatises on the Nature of Science, Indianapolis: Hacket.

- De Lacy P (1972). "Galen's Platonism". American Journal of Philosophy. 1972 (1): 27–39. doi:10.2307/292898. JSTOR 292898.

- Cosans C (1997). "Galen's Critique of Rationalist and Empiricist Anatomy". Journal of the History of Biology. 30 (1): 35–54. doi:10.1023/a:1004266427468. PMID 11618979.

- Cosans C (1998). "The Experimental Foundations of Galen's Teleology". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. 29: 63–80. doi:10.1016/s0039-3681(96)00005-2.

- De Vos (2010). "European Materia Medica in Historical Texts: Longevity of a Tradition and Implications for Future Use". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 132 (1): 28–47. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.035. PMC 2956839. PMID 20561577.

- Heinrich von Staden, "Liminal Perils: Early Roman Receptions of Greek Medicine", in Tradition, Transmission, Transformation, ed. F. Jamil Ragep and Sally P. Ragep with Steven Livesey (Leiden: Brill, 1996), pp. 369-418.

Bibliography

- Connor, J. T. H. An English Language Bibliography of Classical Greek Medicine

Further reading

- Annas, Julia. Classical Greek Philosophy. In Boardman, John; Griffin, Jasper; Murray, Oswyn (ed.) The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press: New York, 1986. ISBN 0-19-872112-9

- Barnes, Jonathan. Hellenistic Philosophy and Science. In Boardman, John; Griffin, Jasper; Murray, Oswyn (ed.) The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press: New York, 1986. ISBN 0-19-872112-9

- Cohn-Haft, Louis. The Public Physicians of Ancient Greece, Northampton, Massachusetts, 1956.

- Guido, Majno. The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World, Harvard University Press, 1975.

- Guthrie, W. K. C. A History of Greek Philosophy. Volume I: The earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans. Cambridge University Press: New York, 1962. ISBN 0-521-29420-7

- Jones, W. H. S. Philosophy and Medicine in Ancient Greece, Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1946.

- Lennox, James (2006-02-15). "Aristotle's Biology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Longrigg, James. Greek Rational Medicine: Philosophy and Medicine from Alcmæon to the Alexandrians, Routledge, 1993.

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. Harvard University Press, 1936. Reprinted by Harper & Row, ISBN 0-674-36150-4, 2005 paperback: ISBN 0-674-36153-9

- Mason, Stephen F. A History of the Sciences. Collier Books: New York, 1956.

- Mayr, Ernst. The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1982. ISBN 0-674-36445-7

- Nutton, Vivian. The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World. Routledge, 2004

- Heinrich von Staden (ed. trans.). Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-521-23646-0, ISBN 978-0-521-23646-1]

- Longrigg, James. Greek Medicine From the Heroic to the Hellenistic Age. New York, NY, 1998. ISBN 0-415-92087-6

External links

- Ancient Greek Medicine in medicinenet.com

- Greek Medicine by the History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine.

- (in French and English) Medicine in Antiquity

- greekmedicine.net

- Greek and Roman Medicine: An Introductory Bibliography for Graduate Students in Classics at Ancient Medicine compiled by Lee T. Pearcy