Cumae

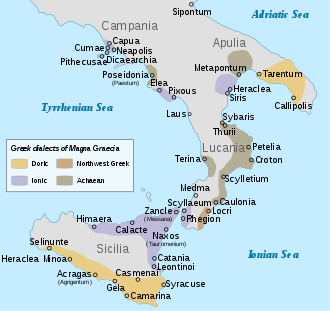

Cumae (Ancient Greek: Κύμη, romanized: (Kumē) or Κύμαι (Kumai) or Κύμα (Kuma);[1] Italian: Cuma) was the first ancient Greek colony on the mainland of Italy, founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BC and soon becoming one of the strongest colonies. It later became a rich Roman city, the remains of which lie near the modern village of Cuma, a frazione of the comune Bacoli and Pozzuoli in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, Italy.

Κύμη / Κύμαι / Κύμα Cuma | |

The terrace of the Temple of Apollo | |

Shown within Italy | |

| Location | Cuma, Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Magna Graecia |

| Coordinates | 40°50′55″N 14°3′13″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Colonists from Euboea |

| Founded | 8th century BC |

| Abandoned | 1207 AD |

| Periods | Archaic Greek to High Medieval |

| Associated with | Cumaean Sibyl, Gaius Blossius |

| Events | Battle of Cumae |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Direzione Regionale per i Beni Culturali e Paesaggistici della Campania |

| Website | Sito Archeologico di Cuma (in Italian) |

The archaeological museum of the Campi Flegrei in the Aragonese castle contains many finds from Cumae.

History

Early

The oldest archaeological finds by Emil Stevens in 1896 date to 900-850 BC[2][3] and more recent excavations have revealed a bronze-age settlement of the "pit-culture" people and later dwellings of Iron Age peoples whose memory was preserved as cave-dwellers named Cimmerians, among whom there was already an oracular tradition.[4]

The Greek settlement was founded in the 8th century BC by emigrants from cities of Eretria and Chalcis in Euboea. The Greeks were already established at nearby Pithecusae (modern Ischia)[5] and were led to Cumae by the joint oecists (founders): Megasthenes of Chalcis and Hippocles of Cyme.[6]

The site chosen was on the hill and later acropolis of Monte di Cuma surrounded on one side by the sea and on the other by particularly fertile ground on the edge of the Campanian plain. While continuing their maritime and commercial traditions, the settlers of Cumae strengthened their political and economic power by exploitation of the land and extended their territory at the expense of neighbouring peoples.

The colony thrived and in the 8th century it was already strong enough to send Perieres to found Zancle in Sicily,[7] and another group to found Tritaea in Achaea, Pausanias was told.[8] Cuma established its dominance over almost the entire Campanian coast up to Punta Campanella over the 7th and 6th centuries BC, gaining sway over Puteoli and Misenum.

The colony spread Greek culture in Italy and introduced the Euboean alphabet, a dialect of Greek and a variant of which was adapted and modified by the Etruscans and then by the Romans and became the Latin alphabet still used worldwide today.

According to Dionysius .. Cumae was at that time celebrated throughout all Italy for its riches, power, and all the other advantages, as it possessed the most fertile part of the Campanian plain and was mistress of the most convenient havens round about Misenum.[9]

The growing power of the Cumaean Greeks led many indigenous tribes of the region to organise against them, notably the Dauni and Aurunci with the leadership of the Capuan Etruscans. This coalition was defeated by the Cumaeans in 524 BC under the direction of Aristodemus. The glorious victories of the colony increased its prestige, so much so that according to Diodorus Siculus, it was usual to associate the whole region of the Phlegraean Fields with Cumaean territory.

At this time the Roman senate sent agents to Cumae to purchase grain in anticipation of a siege of Rome.[10] Then in 505 BC Aristodemus led a Cumaean contingent to assist the Latin city of Aricia in defeating the Etruscan forces of Clusium (see War between Clusium and Aricia) and having become popular with the people he overthrew the aristocratic faction and became a tyrant himself.

Further contact between the Romans and the Cumaeans occurred during the reign of Aristodemus. Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last legendary King of Rome, lived his life in exile with Aristodemus at Cumae after the Battle of Lake Regillus and died there in 495 BC.[11] Livy records that Aristodemus became the heir of Tarquinius, and in 492 when Roman envoys travelled to Cumae to purchase grain, Aristodemus seized the envoys' vessels on account of the property of Tarquinius which had been seized at the time of Tarquinius' exile.[12]

Eventually the exiled nobles and their sons were able to take possession of Cumae and Aristodemus was assassinated in 490 BC.[13]

The combined fleets of Cumae and Syracuse (on Sicily) defeated the Etruscans at the Battle of Cumae in 474 BC. Cumae founded Neapolis in 470 BC.

The temple of Apollo sent the revered Sibylline Books to Rome in the 5th c. BC. Also Rome obtained its priestesses who administered the important cult of Ceres from the temple of Demeter in Cumae.

Oscan and Roman Cumae

-6.jpg)

_01.jpg)

The Greek period at Cumae came to an end in 421 BC, when the Oscans allied to the Samnites broke down the walls and took the city, ravaging the countryside. Some survivors fled to Neapolis.[14] The walls on the acropolis were rebuilt from 343 BC. Cumae came under Roman rule with Capua and in 338 BC was granted partial citizenship, a civitas sine suffragio. In the Second Punic War, in spite of temptations to revolt from Roman authority,[15] Cumae withstood Hannibal's siege, under the leadership of Tib. Sempronius Gracchus.[16]

The city prospered in the Roman period from the 1st c. BC along with all the cities of Campania and especially the bay of Naples as it became a desirable area for wealthy Romans who built large villas along the coast. The "central baths" and the amphitheatre are built.

During the civil wars Cumae was one of the strongholds that Octavian used to defend against Sextus Pompey. Under Augustus extensive public building works and roads were begun and in or near Cumae several road tunnels were dug: one through the Monte di Cumae linking the forum with the port, the Grotta di Cocceio 1 km long to Lake Averno and a third, the "Crypta Romana", 180m long between Lake Lucrino and Lake Averno. The temples of Apollo and Demeter were restored.

The proximity to Puteoli, the commercial port of Rome and to Misenum, the naval fleet base, also helped the region to prosper.

Another very important innovation was the construction of the great Serino aqueduct, the Aqua Augusta supplying many of the cities in the area from about 20 BC. Domitian's via Domitiana provided an important highway to the via Appia and thence to Rome from 95 AD.

The early presence of Christianity in Cumae is shown by the 2nd-century AD work The Shepherd of Hermas, in which the author tells of a vision of a woman, identified with the church, who entrusts him with a text to read to the presbyters of the community in Cuma. At the end of the 4th century, the temple of Zeus at Cumae was transformed into a Christian basilica.

The first historically documented bishop of Cumae was Adeodatus, a member of a synod convoked by Pope Hilarius in Rome in 465. Another was Misenus, who was one of the two legates that Pope Felix III sent to Constantinople and who were imprisoned and forced to receive Communion with Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople in a celebration of the Divine Liturgy in which Peter Mongus and other Miaphysites were named in the diptychs, an event that led to the Acacian Schism. Misenus was excommunicated on his return but was later rehabilitated and took part as bishop of Cumae in two synods of Pope Symmachus. Pope Gregory the Great entrusted the administration of the diocese of Cumae to the bishop of Misenum. Later, both Misenum and Cumae ceased to be residential sees and the territory of Cumae became part of the diocese of Aversa after the destruction of Cumae in 1207.[17][18][19] Accordingly, Cumae is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[20]

Under Roman rule, so-called "quiet Cumae"[21] was peaceful until the disasters of the Gothic Wars (535–554), when it was repeatedly attacked, as the only fortified city in Campania aside from Neapolis: Belisarius took it in 536, Totila held it, and when Narses gained possession of Cumae, he found he had won the whole treasury of the Goths.

Diocese of Cuma(e)

- Not to be confused with the namesake Cuma (Aeolis) in Asia Minor

A bishopric was established around 450 AD. In 700 it gained territory from the suppressed Diocese of Miseno.

In 1207 it was suppressed itself, when forces from Naples, acting for the boy-King of Sicily, destroyed the city and its walls, as the stronghold of a nest of bandits. Its territory was divided and merged into the Roman Catholic Diocese of Aversa and Roman Catholic Diocese of Pozzuoli. Some of the citizens from Cumae, including the clergy and the cathedral capitular, took shelter in Giugliano.

Resident bishops

- Saint Massenzio (300? – ?)

- Rainaldo (1073? – 1078?)

- Giovanni (1134? – 1141?)

- Gregorio (1187? – ?)

- Leone (1207? – ?)

Titular see

In 1970, the diocese was nominally restored as a Latin titular see. The title has been held by:

- Bishop Louis-Marie-Joseph de Courrèges d’Ustou (1970.09.02 – 1970.12.10)

- Archbishop Edoardo Pecoraio (1971.12.28 – 1986.08.09)

- Bishop Julio María Elías Montoya, O.F.M.

Archaeology

Despite the abandonment of the area of Cumae due to the formation of marshes, the memory of the ancient city remained alive. The ruins, although in a state of neglect, were later visited by many artists and with the repopulation of the area due to land reclamation, short excavation campaigns were made. The first excavations date to 1606 when thirteen statues and two marble bas-reliefs were found; later finds included the large statue of Jupiter from the Masseria del Gigante exhibited at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. However, after the discovery of the Vesuvian sites the attention of the Bourbon explorers was diverted there and the Cumae area was abandoned and plundered of numerous finds which were then sold to private individuals. A first campaign of systematic excavations took place between 1852 and 1857 under Prince Leopoldo, brother of Ferdinando II of the Two Sicilies[22] when the area of the Masseria del Gigante and some necropoles were explored. Later Emilio Stevens was given the concession and worked at Cumae between 1878 and 1893, completing the excavation of the necropolis, even though news of the various finds led to a continuous looting of the area.

A disaster occurred between 1910 and 1922 when draining of Lake Licola caused part of the necropolis to be destroyed.

The explorations of the acropolis started in 1911, bringing to light the Temple of Apollo. Between 1924 and 1934 Amedeo Maiuri and Vittorio Spinazzola investigated the Temple of Jupiter, the Cave of the Sibyl and the Crypta Romana, while between 1938 and 1953 the lower city was explored. A chance discovery occurred in 1992 when during the construction of a gas pipeline near the beach a temple of Isis was discovered. In 1994 the "Kyme" project was activated for the restoration of the site. Excavation of the tholos tomb was completed, first partly explored in 1902. In the area of the forum a basilica-shaped building, the Aula Sillana, was discovered, while along the coastline three maritime villas were found.

Since 2001 the CNRS has been excavating a necropolis dating from 6th to 1st c. BC outside the Porta mediana.[23]

In June 2018 a painted tomb dating to the 2nd century BC and depicting a banquet scene was discovered.[24]

Development of the ancient city

The ancient city was divided into two zones, namely the acropolis and the lower part on the plains and the coast.[25] The acropolis was accessible only from the south side and it was on this area that the first nucleus of the city developed crossed by a road called Via Sacra leading to the main temples. The road began with two towers, one of which collapsed with part of the hill and the other was restored in the Byzantine era and is still visible. The lower city developed from the Samnite period and to a greater extent during the Roman age.

The lower city was defended by walls and during the Greek age the acropolis had probably the same type of defences, even if the remains today dating back to the 6th century BC are only on the southeastern part of the hill perhaps also used as retaining walls of the ridge.

In the 6th c. BC temples were built in tufa, wood and terracotta. Columns, cornices and capitals were made of yellow tufa, roofs and architraves of wood and to protect the overhang, terracotta tiles and elaborate antefix decorations. The city and acropolis walls were built from 505 BC, as well as the Sibyl's cave.

When the city was allied with the Romans in 338 BC a new temple was built with exceptional painted friezes and ornamentation which have been discovered though the temple was destroyed after a few decades by fire.

Between the Punic Wars and the adoption of Latin as the official trading language (180 BC) the city walls were restored and a large stadium built west of the Porta mediana. The central baths were built and major work was done on the acropolis temples. From the end of the 2nd c. BC Cumae's architecture became increasingly romanised.

The Augustan age saw many fine new buildings in the city such as the basilica or "Sullan Aula" south of the forum, decorated with polychrome marble. Water supply to the town was increased by an extension to the town of the great Serino aqueduct, the Aqua Augusta, after 20 BC and paid for by local benefactors, the Lucceii family, praetors of the city, who also built an elaborate nymphaeum in the forum as well as several other monuments and buildings.

In the 1st c. AD the "temple of the portico" was built, now embedded in a farmhouse.

Surviving ancient monuments

The visible monuments include:

- Temple of Diana

- Capitoline temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva

- Temple of Isis

- Temple of Demeter

- Temple of Apollo

- The Acropolis

- Arco Felice

- the forum

- Grotta di Cocceio

- Crypta Romana

- Masseria del Gigante

Arco Felice

The Arco Felice was a 20 m high monumental entrance to the city built in a cut through Monte Grillo which Domitian made in 95 AD to avoid the long detour imposed by the via Appia, and allow easier access to Cumae along what was later called the via Domitiana while the bridge also carried a road along the ridge of the hill. It was built of brick and tiled in marble, and surmounted by two rows of arches of lighter concrete covered with brick. The piers had three niches on both sides where statues were placed.

The via Domitiana, whose paving is still perfectly preserved and is in continuous use today, connected to the via Appia, the artery of communication with Rome, as well as with Pozzuoli and Naples.

The arch probably replaced a smaller gate from Greek times and in a higher position.

Crypta Romana

The Crypta Romana is a tunnel dug into the tufa under the Cuma hill, crossing the acropolis in an east-west direction, giving an easier route from the city to the sea. Its construction is part of the set of military enhancement works built by Agrippa for Augustus and designed by Lucius Cocceius Auctus in 37 BC, including the construction of the new Portus Iulius and its connection with the port of Cumae through the so-called Grotta di Cocceio and the Crypta Romana itself.

With the displacement of the fleet from Portus Iulius to the port of Miseno in 12 BC and the end of the Civil War between Octavian and Mark Antony in 31 BC the tunnel lost its strategic value. The forum entrance was made monumental with 4 statue niches in 95 AD at the same time as the Arco Felice was built.[26] An avalanche closed the sea entrance in the 3rd c. After 397 it was reopened. In the christian age it was used as a cemetery area; in the 6th c. the Byzantine general Narsete tried to use it to reach the city during the siege of Cumae, but weakened the structure and a large section of the vault collapsed.

It was brought to light between 1925 and 1931 by the archaeologist Amedeus Maiuri.

Sculpture

- Colossal Jupiter statue (Naples museum)

- Votive relief 400 BC (Antikensammlung Berlin)

_Forum_1-2cAD.jpg) Psyche+Eros, forum 1-2c AD

Psyche+Eros, forum 1-2c AD nymph

nymph Diana

Diana

Mythology

Cumae is perhaps most famous as the seat of the Cumaean Sibyl. Her sanctuary is now open to the public.

In Roman mythology, there is an entrance to the underworld located at Avernus, a crater lake near Cumae, and was the route Aeneas used to descend to the Underworld.

Gallery

Notes and references

- Perseus: Κύ̂μα

- Paolo Caputo u. a.: Cuma e il suo Parco Archeologico. Un territorio e le sue testimonianze. Bardi, Roma 1996

- Eusebius of Caesarea placed Cumae's Greek foundation at 1050 BC; modern archaeology has not detected the first settlers' graves, but fragments of Greek pottery ca 750-40 have been found by the city wall (Robin Lane Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer, 2008:140).

- Strabo, v.5, noted in Elizabeth Hazelton Haight, "Cumae in Legend and History" The Classical Journal 13.8 (May 1918:565-578) p. 567.

- Strabo, v.4.

- Lane Fox 2008:140 notes that whether the Euboeans were from the Ischian colony or freshly arrived is a moot question.

-

- Thucydides, 4, 4

- Pausanias, vii.22.6.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus: Roman Antiquities VII, 2

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.9

- Livy, ii.21; Cicero, Tusculan Disputations iii.27.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2:34

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, vii.3; Plutarch tells the story of Xenocrite, the girl who roused the Cumaeans against Aristodemus, in De mulierum virturibus 26.

- Livy, iv.44; Diodorus Siculus, xii. 76.

- Livy, xxiii.35

- Livy, xxiii.35-37.

- Camillo Minieri Riccio, Cenni storici sulla distrutta città di Cuma, Napoli 1846, pp. 37–38

- Giuseppe Cappelletti, Le Chiese d'Italia dalla loro origine sino ai nostri giorni, vol. XIX, Venezia 1864, pp. 526–535

- Francesco Lanzoni, Le diocesi d'Italia dalle origini al principio del secolo VII (an. 604), vol. I, Faenza 1927, pp. 206–210

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 877

- Juvenal, Satire III

- Paolo Caputo u. a.: Cuma e il suo Parco Archeologico. Un territorio e le sue testimonianze. Bardi, Roma 1996

- http://centrejeanberard.cnrs.fr/spip.php?article34&lang=fr

- "Painted tomb discovered in Cumae (Italy) : A banquet frozen in time". CNRS. 25 September 2018.

- http://kyme.altervista.org/sito/il-parco-archeologico/

- McKAY, A. (1997). THE MONUMENTS OF CUMAE. Vergilius (1959-), 43, 78-88. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41587083

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cumae. |