Kos

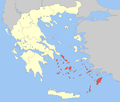

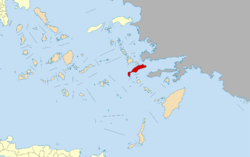

Kos or Cos (/kɒs, kɔːs/; Greek: Κως [kos]) is a Greek island, part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese by area, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 33,388 (2011 census), making it the second most populous of the Dodecanese, after Rhodes.[1] The island measures 40 by 8 kilometres (25 by 5 miles). Administratively, Kos constitutes a municipality within the Kos regional unit, which is part of the South Aegean region. The principal town of the island and seat of the municipality is Kos Town.[2]

Kos Κως | |

|---|---|

The harbour of Kos town | |

Kos Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 36°51′N 27°14′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | South Aegean |

| Regional unit | Kos |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 290.3 km2 (112.1 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 67.2 km2 (25.9 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 843 m (2,766 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 33,387 |

| • Municipality density | 120/km2 (300/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 19,432 |

| • Municipal unit density | 290/km2 (750/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 853 xx |

| Area code(s) | 22420 |

| Vehicle registration | ΚΧ, ΡΟ, PK |

| Website | www.kos.gr |

Name

The name Kos (Ancient Greek: Κῶς, genitive Κῶ)[3] is first attested in the Iliad, and has been in continuous use since. Other ancient names include Meropis,[4] Cea,[5] and Nymphaea.[6]

In many Romance languages, Kos was formerly known as Stancho, Stanchio, or Stinco, and in Ottoman and modern Turkish it is known as İstanköy, all from the reinterpretation of the Greek expression εις την Κω 'to Kos';[7] cf. the similar Istanbul and Stimpoli, Crete. Under the rule of the Knights Hospitaller of Rhodes, it was known as Lango or Langò, presumably because of its length.[8][9] In The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, the author misunderstands this and treats Lango and Kos as distinct islands.[10]

In Italian, the island is known as Coo.

A person from Kos is called a "Koan" in English. The word is also an adjective, as in "Koan goods".[11]

Geography

Kos is in the Aegean Sea. Its coastline is 112 kilometres (70 miles) long and it extends from west to east.

The island has several promontories, some with names known in antiquity: Cape Skandari, anciently Scandarium or Skandarion in the northeast;[12] Cape Lacter or Lakter in the south;[13] and Cape Drecanum or Drekanon in the west.[14]

In addition to the main town and port, also called Kos, the main villages of Kos island are Kardamena, Kefalos, Tingaki, Antimachia, Mastihari, Marmari and Pyli. Smaller ones are Zia, Zipari, Platani, Lagoudi and Asfendiou.

Municipality

The present municipality of Kos was created in 2011 with the merger of three municipalities, which became municipal units:[2]

- Dikaios

- Irakleides

- Kos

The municipality has an area of 290,313 km2, and has a municipal unit of 67.200 km2.[15]

Economy

Tourism is the main industry in Kos, the island's beaches being the primary attraction. The main port and population centre on the island, Kos town, is also the tourist and cultural centre, with whitewashed buildings including many hotels, restaurants and a number of nightclubs forming the Kos town "barstreet". The seaside village of Kardamena is a popular resort for young holidaymakers (primarily from the United Kingdom and Scandinavia) and has a large number of bars and nightclubs.

Farming is the second principal occupation, with the main crops being grapes, almonds, figs, olives, and tomatoes, along with wheat and corn. Cos lettuce may be grown here, but the name is unrelated.

History

Mycenaean Era

In Homer's Iliad, a contingent of Koans fought for the Greeks in the Trojan War.[16]

In classical mythology the founder-king of Kos was Merops, hence "Meropian Kos" is included in the archaic Delian amphictyony listed in the 7th-century Homeric hymn to Delian Apollo; the island was visited by Heracles.[17]

The island was originally colonised by the Carians. The Dorians invaded it in the 11th century BC, establishing a Dorian colony with a large contingent of settlers from Epidaurus, whose Asclepius cult made their new home famous for its sanatoria. The other chief sources of the island's wealth lay in its wines and, in later days, in its silk manufacture.[18]

Archaic Era

Its early history–as part of the religious-political amphictyony that included Lindos, Kamiros, Ialysos, Cnidus and Halicarnassus, the Dorian Hexapolis (hexapolis means six cities in Greek),[19]–is obscure. At the end of the 6th century, Kos fell under Achaemenid domination but rebelled after the Greek victory at the Battle of Mycale in 479.

Classical Era

During the Greco-Persian Wars, before it twice expelled the Persians, it was ruled by Persian-appointed tyrants, but as a rule it seems to have been under oligarchic government. In the 5th century, it joined the Delian League, and, after the revolt of Rhodes, it served as the chief Athenian station in the south-eastern Aegean (411–407). In 366 BC, a democracy was instituted. In 366 BC, the capital was transferred from Astypalaea (at the west end of the island near the modern village of Kefalos) to the newly built town of Cos, laid out in a Hippodamian grid. After helping to weaken Athenian power, in the Social War (357-355 BC), it fell for a few years to the king Mausolus of Caria.

Proximity to the east gave the island first access to imported silk thread. Aristotle mentions silk weaving conducted by the women of the island.[20] Silk production of garments was conducted in large factories by female slaves.[21]

Hellenistic Era

During the course of the Fourth War of the Diadochi Ptolemy I Soter captures Kos from Antigonus I Monophthalmus, incorporating it into his kingdom.[22] In the Hellenistic period, Kos attained the zenith of its prosperity. Kos was valued by the Ptolemies, who used it as a naval outpost to oversee the Aegean. As a seat of learning, it arose as a provincial branch of the museum of Alexandria, and became a favorite resort for the education of the princes of the Ptolemaic dynasty. During the Hellenistic age, there was a medical school; however, the theory that this school was founded by Hippocrates (see below) during the Classical age is an unwarranted extrapolation.[23] It was the home of the major Hellenistic poet-scholar Philitas.

Kos also became a center of production of unrefined silk, oars and amphorae.[24] Kos economic development during the period can further be exemplified by the 3rd and 2nd century BC construction of a theater, a new market with multiple stoas, a temple to Apollo at Alisarna, construction and expansion of the Asclepeion, fortification works at Alisarna and multiple richly decorated houses.[25] In 240 BC, Ziaelas of Bithynia, Seleucus II Callinicus and Ptolemy III Euergetes provided guarantees for the transformation of Kos Asclepeion into an asylum. This decision made Kos a more attractive destination for merchants and pilgrims.[26]

Diodorus Siculus (xv. 76) and Strabo (xiv. 657) describe it as a well-fortified port. Its position gave it a high importance in Aegean trade; while the island itself was rich in wines of considerable fame.[27] Under Alexander the Great and the Ptolemies the town developed into one of the great centers in the Aegean; Josephus[28] quotes Strabo to the effect that Mithridates I of the Bosporus was sent to Kos to fetch the gold deposited there by queen Cleopatra of Egypt. Herod is said to have provided an annual stipend for the benefit of prize-winners in the athletic games,[29] and a statue was erected there to his son Herod the Tetrarch ("C. I. G." 2502 ). Paul briefly visited Kos according to Acts 21:1.

Roman Era

Except for occasional incursions by corsairs and some severe earthquakes, the island's peace has rarely been disturbed. Following the lead of its larger neighbour, Rhodes, Kos generally displayed a friendly attitude toward the Romans; in 53 AD it was made a free city. It was known in antiquity for the manufacture of transparent light dresses, the coae vestes.[30] The island of Kos also featured a provincial library during the Roman period. The island first became a center for learning during the Ptolemaic dynasty, and Hippocrates, Apelles, Philitas and possibly Theocritus came from the area. An inscription lists people who made contributions to build the library in the 1st century AD.[31] One of the people responsible for the library's construction was the Kos doctor Gaius Stertinius Xenophon, who lived in Rome and was the personal physician of the Emperors Tiberius, Claudius, and Nero.[32]

Byzantine Era

The bishopric of Kos was a suffragan of the metropolitan see of Rhodes.[33] Its bishop Meliphron attended the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Eddesius was one of the minority Eastern bishops who withdrew from the Council of Sardica in about 344 and set up a rival council at Philippopolis. Iulianus went to the synod held in Constantinople in 448 in preparation for the Council of Chalcedon of 451, in which he participated as a legate of Pope Leo I, and he was a signatory of the joint letter that the bishops of the Roman province of Insulae sent in 458 to Byzantine Emperor Leo I the Thracian with regard to the killing of Proterius of Alexandria. Dorotheus took part in a synod in 518. Georgius was a participant of the Third Council of Constantinople in 680–681. Constantinus went to the Photian Council of Constantinople (879).[34][35] Under Byzantine rule, apart from the participation of its bishops in councils, the island's history remains obscure. It was governed by a droungarios in the 8th–9th centuries, and seems to have acquired some importance in the 11th and 12th centuries: Nikephoros Melissenos began his uprising here, and in the middle of the 12th century, it was governed by a scion of the ruling Komnenos dynasty, Nikephoros Komnenos.[33]

Today the metropolis of Kos remains under the direct authority of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, rather than the Church of Greece, and is also listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[36]

Following the Fourth Crusade, Kos passed under Genoese control, although it was retaken in ca. 1224 and kept for a while by the Empire of Nicaea.[33] In the 1320s, Kos nominally formed part of the realm of Martino Zaccaria, but was most likely in the hands of Turkish corsairs until ca. 1337, when the Knights Hospitaller took over the island.[33] The last Hospitaller governor of the island was Piero de Ponte.

Ottoman Era

The Ottoman Empire captured the island in early 1523.[33] The Ottomans ruled Kos until 1911.

According to the Ottoman General Census of 1881/82-1893, the kaza of Kos (Istanköy) had a total population of 12,965, consisting of 10,459 Greeks, 2,439 Muslims and 67 Jews.[37]

Italian Rule

Kos was transferred to the Kingdom of Italy in 1912 after the Italo-Turkish War.[38] The Italians developed the infrastructures of the island, after the ruinous earthquake of 23 April 1933, which destroyed a great part of the old city and damaged many new buildings. Architect Rodolfo Petracco drew up the new city plan, transforming the old quarters into an archaeological park, and dividing the new city into a residential, an administrative, and a commercial area.,[39] In World War II, the island, as Italian possession, was part of the Axis. It was controlled by Italian troops until the Italian surrender in 1943. On that occasion, 100 Italian officers who had refused to join the Germans were executed. British and German forces then clashed for control of the island in the Battle of Kos as part of the Dodecanese Campaign, in which the Germans were victorious. German troops occupied the island until 1945, when it became a protectorate of the United Kingdom, which ceded it to Greece in 1947 following the Paris peace treaty.

Geology

The island is part of a chain of mountains from which it became separated after earthquakes and subsidence that occurred in ancient times. These mountains include Kalymnos and Kappari which are separated by an underwater chasm c. 70 metres (230 ft) (40 fathoms deep), as well as the volcano of Nisyros and the surrounding islands.

There is a wide variety of rocks in Kos which is related to its geographical formation. Prominent among these are the Quaternary layers in which the fossil remains of mammals such as horses, hippopotami and elephants have been found. The fossilised molar of an elephant of gigantic proportions was presented to the Paleontology Museum of the University of Athens.

Demographics

Turkish population

In the late 1920s about 3,700 Turks lived in Kos city, slightly less than 50% of the population, who settled mainly in the west part of the city.[40] Today, the population of the Turkish community in Kos has been estimated at about 2,000 people.[41][42] A village with significant Turkish population is Platani (Kermentes) near the town of Kos.

Religion

The people of Kos are predominantly Orthodox Christians - one of the four Orthodox cathedrals in the Dodecanese is located in Kos. In addition, there is a Roman Catholic church on the island and a mosque for the Turkish-speaking Muslim community. The synagogue is no longer used for religious ceremonies as the Jewish community of Kos was targeted and destroyed by occupying Nazi forces in World War II. It has, however, been restored and is maintained with all religious symbols intact and is now used by the Municipality of Kos for various events, mainly cultural.

Main sights

Castles

The island has a 14th-century fortress at the entrance to its harbour, erected in 1315 by the Knights Hospitaller, and another from the Byzantine period in Antimachia.

Ancient Agora

The ancient market place of Kos was considered one of the biggest in the ancient world. It was the commercial and commanding centre at the heart of the ancient city. It was organized around a spacious rectangular yard 50 metres (160 ft) wide and 300 metres (980 ft) long. It began in the Northern area and ended up south on the central road (Decumanus) which went through the city. The northern side connected to the city wall towards the entrance to the harbour. Here there was a monumental entrance. On the eastern side there were shops. In the first half of the 2nd century BC, the building was extended toward the interior yard. The building was destroyed in an earthquake in 469 AD.

In the southern end of the market, there was a round building with a Roman dome and a workshop which produced pigments including "Egyptian Blue". Coins, treasures, and copper statues from Roman times were later uncovered by archeologists. In the western side excavations led to the findings of rooms with mosaic floors which showed beastfights, a theme quite popular in Kos.[43]

Culture

The ancient physician Hippocrates is thought to have been born on Kos, and in the center of the town is the Plane Tree of Hippocrates, a dream temple where the physician is traditionally supposed to have taught. The limbs of the now elderly tree are supported by scaffolding. The small city is also home to the International Hippocratic Institute and the Hippocratic Museum dedicated to him. Near the Institute are the ruins of Asklepieion, where Herodicus taught Hippocrates medicine.

People

- Epicharmus of Kos (6th-5th century BC), comic playwright

- Hippocrates (5th century BC), "father of medicine".

- Philitas of Cos (4th century BC), poet and scholar.

- Michael Kefalianos, professional bodybuilder.[44]

- Marika Papagika, early 20th century singer.[45]

- Kostas Skandalidis, former Interior Minister of Greece and close associate of Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou.[46]

- Al Campanis, Major League Baseball player and executive.[47]

- Stergos Marinos, international footballer currently playing for Panathinaikos.[48]

- Şükrü Kaya, Turkish politician, who served as Minister of the Interior and Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey. He was one of the perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide.[49]

In popular culture

Kos is the setting of the wargaming book 'Swords of Kos Fantasy Campaign Setting', written by Michael O. Varhola with co-authors.[50]

Gallery

Ancient Agora

Ancient Agora- Archaeological Museum of Kos

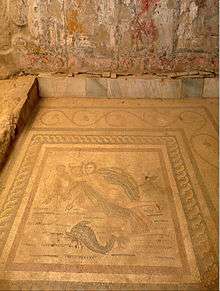

Mosaic depicting Asclepius and Hippocrates (3rd century), AM of Kos

Mosaic depicting Asclepius and Hippocrates (3rd century), AM of Kos Town hall

Town hall- St Paraskevi church, Kos town

Street of Kos town

Street of Kos town

See also

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- Kallikratis law Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Greece Ministry of Interior (in Greek)

- Liddell et al., A Greek–English Lexicon, s.v.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. 8.41.

- Pliny cites Staphylus of Naucratis for this name in the Natural History 5:36 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, but Peck apparently misinterprets Staphylus as a name of Kos

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898, s.v. Cos Archived 16 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- C.S. Sonnini, Travels in Greece and Turkey, undertaken by order of Louis XVI, and with the authority of the Ottoman court, London, 1801, 1 p. 212

- A handbook for travellers in Greece, Murray's Handbooks, 4th edition, London, 1872, p. 364

- H.J.A. Sire, The Knights of Malta, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068859, p. 34

- Anthony Bale, trans., The Book of Marvels and Travels, Oxford 2012, ISBN 0199600600, p. 15 and footnote

- Kos Island Today Archived 29 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Kosisland.gr.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2015.

- Iliad ii.676, from "Kos, the city of Eurypylus, and the Calydnae isles", under the leaders Phidippos and Antiphos, "sons of the Thessalian king". It is unclear whether Homer is describing cultural affiliations of his own time or remembered traditions of Mycenaean times.

- Hercules in Kos Archived 29 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Kosinfo.gr.

- Money, Power And Gender:Evidence For Influential Women Represented And Sculpture On Kos Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. None.

- The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites (eds. Richard Stillwell, et al.), s.v. "Kos".

- A Treatise on the Origin, Progressive Improvement, and Present State of the Silk Manufacture at Google Books

- Introduction to the New Testament, p. 83, at Google Books

- Sartre 2006, pp. 55–56.

- Vincenzo Di Benedetto: Cos e Cnido, in: Hippocratica - Actes du Colloque hippocratique de Paris 4-9 septembre 1978, ed. M. D. Grmek, Paris 1980, 97-111, see also Antoine Thivel: Cnide et Cos ? : essai sur les doctrines médicales dans la collection hippocratique, Paris 1981 (passim), ISBN 22-51-62021-4; cf. the review by Otta Wenskus (on JSTOR).

- Sartre 2006, pp. 251–254.

- Sartre 2006, pp. 274–275.

- Sartre 2006, pp. 267–269.

- Pliny, xxxv. 46

- "Ant." xiv. 7, § 2

- Josephus, "B. J." i. 21, § 11

-

- "Libraries of Greece". Annette Lamb. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "The Asklepion of Kos – Home of Modern Medicine". The Skibbereen Eagle. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Gregory, Timothy E. (1991). "Kos". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1150. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Raymond Janin, v. Cos in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XIII, Paris 1956, coll. 927-928

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae Archived 8 March 2015 at Wikiwix, Leipzig 1931, p. 448

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 875

- Kemal Karpat (1985), Ottoman Population, 1830-1914, Demographic and Social Characteristics, The University of Wisconsin Press, p. 130-131

- Bertarelli, Luigi Vittorio (1929). Guida d'Italia Vol. XVII. Milano: C.T.I. p. Sub voce "Storia".

- G. Rocco, M. Livadiotti, Il piano regolatore di Kos del 1934: un progetto di città archeologica, "Thiasos", 1, 2012, pp. 10-2 Archived 28 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Bertarelli, Luigi Vittorio (1929). Guida d'Italia, Vol. XVII (1st ed.). Milano: CTI. p. 145.

- Ürkek bir siyasetin tarih önündeki ağır vebali, p. 142, at Google Books

- "MUM GİBİ ERİYORLAR". www.batitrakya.4mg.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Ancient Sites of the Harbour and Market Place Archived 29 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Kosinfo.gr.

- Michael Kefalianos – Bio Archived 22 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine MichaelKefalianos.com

- Steve Sullivan (4 October 2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings. Scarecrow Press. p. 742. ISBN 978-0-8108-8296-6.

- Administrator. "Σκανδαλίδης Κώστας - Βιογραφικό". www.skandalidis.gr. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "www.baseball-reference.com". baseball-reference.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Stergos Marinos biography" (in Greek). Stergos Marinos' official website. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- Who is who database - Biography of Şükrü Kaya Archived 5 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- Varhola, Michael O.; Clunie, Jim; Cass, Brendan; Staples, Clint; Thrasher, William T.; Van Deeleen, Chris; Farnden, Heath (2016). Swords of Kos Fantasy Campaign Setting. Skirmisher Publishing. ISBN 978-1935050742. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

Sources

- Sartre, Maurice (2006). Ελληνιστική Μικρασία: Aπο το Αιγαίο ως τον Καύκασο [Hellenistic Asia Minor: From the Aegean to the Caucaus] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdoseis Pataki. ISBN 9789601617565.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)