Messina

Messina (/mɛˈsiːnə/, also US: /mɪˈ-/,[3][4][5] Italian: [mesˈsiːna] (![]()

Messina | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan City of Messina | |

| |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

.svg.png) Position of the commune in the Metropolitan City | |

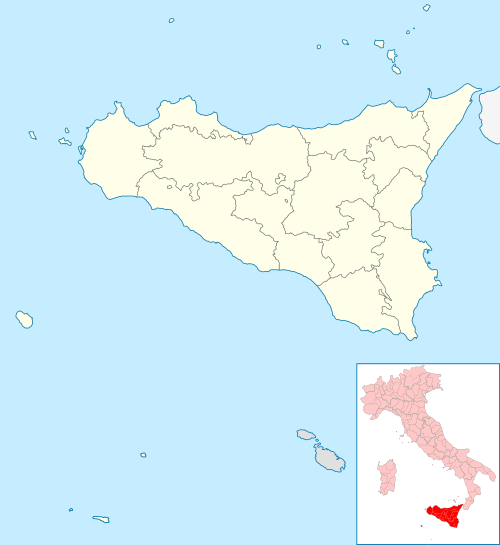

Location of Messina

| |

Messina Location of Messina in Italy  Messina Messina (Sicily) | |

| Coordinates: 38°11′N 15°33′E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Sicily |

| Metropolitan city | Messina (ME) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Cateno De Luca |

| Area | |

| • Total | 213.23 km2 (82.33 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Population (31 March 2019)[2] | |

| • Total | 231,708 |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,800/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Messinese |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 98100 |

| Dialing code | 090 |

| ISTAT code | 083048 |

| Patron saint | Madonna of the Letter |

| Saint day | June 3 |

| Website | Official website |

The city's main resources are its seaports (commercial and military shipyards), cruise tourism, commerce, and agriculture (wine production and cultivating lemons, oranges, mandarin oranges, and olives). The city has been a Roman Catholic Archdiocese and Archimandrite seat since 1548 and is home to a locally important international fair. The city has the University of Messina, founded in 1548 by Ignatius of Loyola.

Messina has a light rail system, Tranvia di Messina, opened on 3 April 2003. This line is 7.7 kilometres (4.8 mi) and links the city's central railway station with the city centre and harbour.

History

_-_Terremoto_di_Messina%2C_1908.jpg)

.jpg)

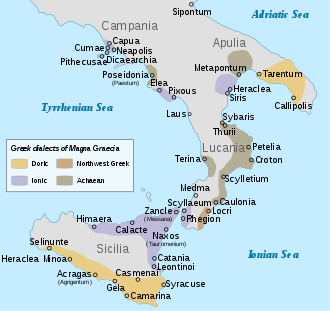

Founded by Greek colonists in the 8th century BC, Messina was originally called Zancle (Greek: Ζάγκλη), from the Greek ζάγκλον meaning "scythe" because of the shape of its natural harbour (though a legend attributes the name to King Zanclus). A comune of its Metropolitan City, located at the southern entrance of the Strait of Messina, is to this day called 'Scaletta Zanclea'. Solinus write that the city of Metauros was established by people from the Zancle.[8]

In the early 5th century BC, Anaxilas of Rhegium renamed it Messene (Μεσσήνη) in honour of the Greek city Messene (See also List of traditional Greek place names). Later, Micythus was the ruler of Rhegium and Zancle, and he also founded the city of Pyxus.[9] The city was sacked in 397 BC by the Carthaginians and then reconquered by Dionysius I of Syracuse.

In 288 BC the Mamertines seized the city by treachery, killing all the men and taking the women as their wives. The city became a base from which they ravaged the countryside, leading to a conflict with the expanding regional empire of Syracuse. Hiero II, tyrant of Syracuse, defeated the Mamertines near Mylae on the Longanus River and besieged Messina. Carthage assisted the Mamertines because of a long-standing conflict with Syracuse over dominance in Sicily. When Hiero attacked a second time in 264 BC, the Mamertines petitioned the Roman Republic for an alliance, hoping for more reliable protection. Although initially reluctant to assist lest it encourage other mercenary groups to mutiny, Rome was unwilling to see Carthaginian power spread further over Sicily and encroach on Italy. Rome therefore entered into an alliance with the Mamertines. In 264 BC, Roman troops were deployed to Sicily, the first time a Roman army acted outside the Italian Peninsula. At the end of the First Punic War it was a free city allied with Rome. In Roman times Messina, then known as Messana, had an important pharos (lighthouse). Messana was the base of Sextus Pompeius, during his war against Octavian.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the city was successively ruled by Goths from 476, then by the Byzantine Empire in 535, by the Arabs in 842, and in 1061 by the Norman brothers Robert Guiscard and Roger Guiscard (later count Roger I of Sicily). In 1189 the English King Richard I ("The Lionheart") stopped at Messina en route to the Holy Land for the Third Crusade and briefly occupied the city after a dispute over the dowry of his sister, who had been married to William the Good, King of Sicily. In 1345 Orlando d'Aragona, illegitimate son of Frederick II of Sicily was the strategos of Messina.

In 1347, Messina was one of the first points of entry for the black death into Western Europe. Genoese galleys traveling from the infected city of Kaffa carried plague into the Messina ports. Kaffa had been infected via Asian trade routes and siege from infected Mongol armies led by Janibeg; it was a departure point for many Italian merchants who fled the city to Sicily. Contemporary accounts from Messina tell of the arrival of "Death Ships" from the East, which floated to shore with all the passengers on board already dead or dying of plague. Plague-infected rats probably also came aboard these ships. The black death ravaged Messina, and rapidly spread northward into mainland Italy from Sicily in the following few months.

In 1548 St. Ignatius founded there the first Jesuit college in the world, which later gave birth to the Studium Generale (the current University of Messina). The Christian ships that won the Battle of Lepanto (1571) left from Messina: the Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes, who took part in the battle, recovered for some time in the Grand Hospital. The city reached the peak of its splendour in the early 17th century, under Spanish domination: at the time it was one of the ten greatest cities in Europe.

In 1674 the city rebelled against the foreign garrison. It managed to remain independent for some time, thanks to the help of the French king Louis XIV, but in 1678, with the Peace of Nijmegen, it was reconquered by the Spaniards and sacked: the university, the senate and all the privileges of autonomy it had enjoyed since the Roman times were abolished. A massive fortress was built by the occupants and Messina decayed steadily. In 1743, 48,000 died of a second wave of plague in the city.[10]

In 1783, an earthquake devastated much of the city, and it took decades to rebuild and rekindle the cultural life of Messina. In 1847 it was one of the first cities in Italy where Risorgimento riots broke out. In 1848 it rebelled openly against the reigning Bourbons, but was heavily suppressed again. Only in 1860, after the Battle of Milazzo, the Garibaldine troops occupied the city. One of the main figures of the unification of Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini, was elected deputy at Messina in the general elections of 1866. Another earthquake of less intensity damaged the city on 16 November 1894. The city was almost entirely destroyed by an earthquake and associated tsunami on the morning of 28 December 1908, killing about 100,000 people and destroying most of the ancient architecture. The city was largely rebuilt in the following year.

It incurred further damage from the massive Allied air bombardments of 1943; before and during the Allied invasion of Sicily. Messina, owing to its strategic importance as a transit point for Axis troops and supplies sent to Sicily from mainland Italy, was a prime target for the British and American air forces, which dropped some 6,500 tons of bombs in the span of a few months.[11] These raids destroyed one third of the city, and caused 854 deaths among the population.[12] The city was awarded a Gold Medal of Military Valor and one for Civil Valor by the Italian government in memory of the event and the subsequent effort of reconstruction.[13]

In June 1955, Messina was the location of the Messina Conference of Western European foreign ministers which led to the creation of the European Economic Community.[14] The conference was held mainly in Messina's City Hall building (it), and partly in nearby Taormina.

The city is home to a small Greek-speaking minority, which arrived from the Peloponnese between 1533-34 when fleeing from the Ottoman Empire. They were officially recognised in 2012.[15]

Climate

Messina has a subtropical mediterranean climate with long, hot summers with low diurnal temperature variation with consistent dry weather. In winter, Messina is rather wet and mild. Diurnals remain low and remain averaging above 10 °C (50 °F) lows even during winter. It is rather rainier than Reggio Calabria on the other side of the Messina Strait, a remarkable climatic difference for such a small distance.

| Climate data for Messina | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.6 (76.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

29.6 (85.3) |

33.6 (92.5) |

43.4 (110.1) |

43.6 (110.5) |

41.8 (107.2) |

40.5 (104.9) |

36.4 (97.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

43.6 (110.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

21.6 (70.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.7 (56.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

16.1 (60.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 102.9 (4.05) |

100.2 (3.94) |

83.4 (3.28) |

68.3 (2.69) |

33.8 (1.33) |

12.7 (0.50) |

20.0 (0.79) |

25.6 (1.01) |

63.9 (2.52) |

113.7 (4.48) |

119.5 (4.70) |

102.9 (4.05) |

846.9 (33.34) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.6 | 9.8 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 5.6 | 8.5 | 11.0 | 10.9 | 83.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 71 | 69 | 69 | 67 | 64 | 63 | 66 | 68 | 70 | 73 | 74 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114.7 | 130.0 | 170.5 | 207.0 | 257.3 | 294.0 | 331.7 | 306.9 | 240.0 | 189.1 | 138.0 | 111.6 | 2,490.8 |

| Source 1: Servizio Meteorologico (temperature and precipitation data 1971–2000);[16] Clima en Messina desde 1957 hasta 2013[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Messina Osservatorio Meteorologico (temperature records since 1909);[18] Servizio Meteorologico (relative humidity and sun data 1961–1990)[19] | |||||||||||||

Government

Main sights

Religious architecture

.jpg)

- The Cathedral (12th century), containing the remains of king Conrad, ruler of Germany and Sicily in the 13th century. The building had to be almost entirely rebuilt in 1919–20, following the devastating 1908 earthquake, and again in 1943, after a fire triggered by Allied bombings. The original Norman structure can be recognised in the apsidal area. The façade has three late Gothic portals, the central of which probably dates back to the early 15th century. The architrave is decorated with a sculpture of Christ Among the Evangelists and various representations of men, animals and plants. The tympanum dates back to 1468. The interior is organised in a nave and two equally long aisles divided by files of 28 columns. Some decorative elements belong the original building, although the mosaics in the apse are reconstructions. Tombs of illustrious men besides Conrad IV include those of Archbishops Palmer (died in 1195), Guidotto de Abbiate (14th century) and Antonio La Legname (16th century). Special interest is held by the Chapel of the Sacrament (late 16th century), with scenic decorations and 14th century mosaics. The bell tower holds the Messina astronomical clock, one of the largest astronomical clocks in the world, built in 1933 by the Ungerer Company of Strasbourg. The belfry's mechanically-animated statues, which illustrate events from the civil and religious history of the city every day at noon, are a popular tourist attraction.

- The Sanctuary of Santa Maria del Carmelo (near the Courthouse), built in 1931, which contains a 17th-century statue of the Virgin Mary. See also Chiesa del Carmine.

- The Sanctuary of Montevergine, where the incorrupt body of Saint Eustochia Smeralda Calafato is preserved.

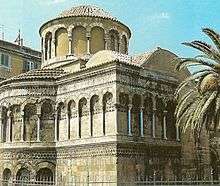

- The Church of the Santissima Annunziata dei Catalani (late 12th–13th century). Dating from the late Norman period, it was transformed in the 13th century when the nave was shortened and the façade added. It has a cylindrical apse and a high dome emerging from a high tambour. Noteworthy is the external decoration of the transept and the dome area, with a series of blind arches separated by small columns, clearly reflecting Arabic architectural influences.

- The Church of Santa Maria degli Alemanni (early 13th century), which was formerly a chapel of the Teutonic Knights. It is a rare example of pure Gothic architecture in Sicily, as is witnessed by the arched windows and shapely buttresses.

_-_Messina_(Sicily)_-_Italy_-_15_Aug._2009_-_(3).jpg)

Civil and military architecture

- The 'Botanical Garden Pietro Castelli of the University of Messina.

- The Palazzo Calapaj, an example of 18th-century Messinese architecture which survived until the 1908 earthquake.

- The Forte del Santissimo Salvatore, a 16th-century fort in the Port of Messina.

- The Forte Gonzaga, a 16th-century fort overlooking Messina.

- The Porta Grazia, 17th-century gate of the "Real Cittadella di Messina", by Domenico Biundo and Antonio Amato, a fortress still existing in the harbour.

- The Pylon, built in 1957 together with a twin located across the Strait of Messina, to carry a 220 kV overhead power line bringing electric power to the island. At the time of their construction, the two electric pylons were the highest in the world. The power line has since been replaced by an underwater cable, but the pylon still stands as a freely accessible tourist attraction.

- The San Ranieri lighthouse, built in 1555.

- The Palace of Culture, built in 2009.

Monuments

- The Fountain of Orion, a monumental civic sculpture located next to the Cathedral, built in 1547 by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli, student of Michelangelo, with a Neoplatonic-alchemical program. It was considered by art historian Bernard Berenson "the most beautiful fountain of the sixteenth century in Europe".

- The Fountain of Neptune, looking towards the harbour, built by Montorsoli in 1557.

- The monument to John of Austria, by Andrea Camalech (1572)

- The Senatory Fountain, built in 1619.

- The Four Fountains, though only two elements of the four-cornered complex survive today.

Museums

- Museo Regionale di Messina (MuMe) hosting notable paintings by Caravaggio, Antonello da Messina, Alonzo Rodriguez, Mattia Preti

- The Galleria d'Arte Contemporanea di Messina, hostings paintings by Giò Pomodoro, Renato Guttuso, Lucio Fontana, Corrado Cagli, Giuseppe Migneco, Max Liebermann

Sports team

- A.C.R. Messina

- S.S.D. Città di Messina

Notable people

List of notable people from Messina or connected to Messina, listed by career and then in alphabetical order by last name.

Actors

- Adolfo Celi, actor (born 1922)

- Tano Cimarosa, actor (born 1922)

- Maria Grazia Cucinotta, actress (born 1968)

- Nino Frassica, actor (born 1950)

- Massimo Mollica, actor (born 1929)

Artists and designers

- Girolamo Alibrandi, painter (born in 1470)

- Anna Maria Arduino (1672 – 1700) 17th century painter, writer and socialite, served as the Princess of Piombino, from Messina.[20]

- Antonio Barbalonga, painter (17th century)

- Francesco Comande, painter (16th century)

- Antonello da Messina, major painter of the Renaissance (born 1430)

- Giuseppe Migneco, painter (born 1908)

- Giovanni Quagliata, painter (born 1603)

- Filippo Juvarra, Baroque architect (born 1678)

- Mariano Riccio, painter (born 1510)

- Alonzo Rodriguez, painter (born 1578)

- Giovanni Tuccari, painter (born 1667)

Politicians, civil service, military

- Giuseppe La Farina, leader of the Italian Risorgimento (born 1815)

- Gaetano Martino, politician, physician and professor. (born 1900)

- Giuseppe Natoli, lawyer and politician (born 1815)

- Luigi Rizzo, naval officer and First World War hero (born 1887)

Musicians, composers

- Mario Aspa, composer (born 1797)

- Filippo Bonaffino (fl. 1623), Italian madrigal composer

Religion

- Eustochia Smeralda Calafato, saint (born 1434)

- Annibale Maria Di Francia, saint (born 1851)

Sports

- Tony Cairoli, motocross world champion (born 1985)

- Vincenzo Nibali, cyclist (born 1984)

Researchers, academics

- Aristocles of Messene, peripatetic philosopher (1st century AD)

- Dicaearchus, Greek philosopher and mathematician (born 350 BC)

- Caio Domenico Gallo, historian (born 1697)

- Francesco Maurolico, astronomer, mathematician and humanist (born 1494)

- Agostino Scilla, painter, paleontologist, geologist and pioneer in the study of fossils (born 1629)

- Giuseppe Seguenza, naturalist and geologist (born 1833)

- Giuseppe Sergi, anthropologist and psychologist (born 1841)

Others

- Stefano D'Arrigo, writer (born 1919)

- Guido delle Colonne, judge and writer (13th century)

- Teneglia Farms, family citrus groves, (19th century)

Literary references

._Messina%2C_Island_of_Sicily%2C_Italy%2C_Southern_Europe.jpg)

Numerous writers set their works in Messina, including:

- Plutarch – The Life of Pompey (40 BC?)

- Giovanni Boccaccio – Decameron IV day V novel, Lisabetta da Messina – IV day IV Novel, Gerbino ed Elissa (1351)

- Matteo Bandello – Novelliere First Part, novel XXII (1554)

- William Shakespeare – Much Ado about Nothing (1598) and Antony and Cleopatra (1607)

- Molière – L'Etourdi ou Les Contre-temps (1654)

- Friedrich Schiller – Die Braut von Messina (The Bride of Messina, 1803)

- Silvio Pellico – Eufemio da Messina (1818)

- Friedrich Nietzsche – Idyllen aus Messina (Idylls from Messina, 1882)

- Giovanni Pascoli – poem L'Aquilone (1904)

- Elio Vittorini – Le donne di Messina (Women of Messina, 1949) and Conversazione in Sicilia (Conversations in Sicily, 1941)

- Stefano D'Arrigo – Horcynus Orca (1975)

- Julien Green – Demain n'existe pas (1985)

See also

- International Rally of Messina

- Messina Centrale railway station

- Messina Grand Prix held between 1959 and 1961

- Strait of Messina Bridge

- Torre Faro 224 metres tall lattice tower

- Zanclean Age of the Pliocene Epoch in geology, named for Zancle, ancient Messina

- Messinian Age of the Miocene Epoch in geology, named for Messina

Notes

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Data from ISTAT

- "Messina" (US) and "Messina". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- "Messina". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- "Messina". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- Population of Messina, Italy Archived 2014-05-13 at the Wayback Machine Geonames Geographical database

- "Population on 1 January by age groups and sex - functional urban areas [urb_lpop1]". Eurostat. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Solinus, Polyhistor, 2.10

- Diodorus Siculus, Library, § 11.59.1

- "Epidemiology of the Black Death and Successive Waves of Plague" by Samuel K Cohn JR. Medical History.

- La Piazza Marittima di Messina (1939-1943)

- Proposta l’istituzione di una “giornata della memoria” degli 854 messinesi morti sotto i bombardamenti del ‘43

- Presidenza della Repubblica

- "''The Messina Declaration 1955'' final document of ''The Conference of Messina'' 1 to 3 June 1955 – birth of the European Union". Eu-history.leidenuniv.nl. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "Delimiting the territory of the Greek linguistic minority of Messina" (PDF).

- "MESSINA" (PDF). Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Messina". Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- "Messina Osservatorio Meteorologico". Servizio Meteorologico dell’Aeronautica Militare. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "MESSINA". Servizio Meteorologico. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Donne in Arcadia (1690-1800)". www.arcadia.uzh.ch. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

Sources

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Messina. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Messina. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Messina. |

- Official website