Philip II of Macedon

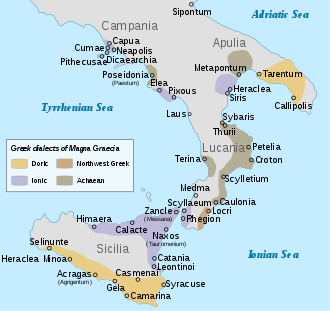

Philip II of Macedon[2] (Greek: Φίλιππος Β΄ ὁ Μακεδών; 382–336 BC) was the king (basileus) of the kingdom of Macedon from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC.[3] He was a member of the Argead dynasty of Macedonian kings, the third son of King Amyntas III of Macedon, and father of Alexander the Great and Philip III. The rise of Macedon, its conquest and political consolidation of most of Classical Greece during the reign of Philip II was achieved in part by his reformation of the Ancient Macedonian army, establishing the Macedonian phalanx that proved critical in securing victories on the battlefield. After defeating the Greek city-states of Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, Philip II led the effort to establish a federation of Greek states known as the League of Corinth, with him as the elected hegemon and commander-in-chief[4] of Greece for a planned invasion of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. However, his assassination by a royal bodyguard, Pausanias of Orestis, led to the immediate succession of his son Alexander, who would go on to invade the Achaemenid Empire in his father's stead.

| Philip | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) Bust of Philip II of Macedon from the Hellenistic period; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek | |||||

| Basileus of Macedon | |||||

| Reign | 359–336 BC | ||||

| Predecessor | Amyntas IV | ||||

| Successor | Alexander the Great | ||||

| Hegemon of the Hellenic League[1] | |||||

| Reign | 337 BC | ||||

| Successor | Alexander the Great | ||||

| Strategos Autokrator of Greece against Achaemenid Empire | |||||

| Reign | 337 BC | ||||

| Successor | Alexander the Great | ||||

| Born | 382 BC Pella, Macedon | ||||

| Died | October 336 BC (aged 46) Aigai, Macedon | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Wives |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Greek | Φίλιππος | ||||

| House | Argead dynasty | ||||

| Father | Amyntas III | ||||

| Mother | Eurydice I | ||||

| Religion | Ancient Greek religion | ||||

Biography

Youth and accession

Philip was the youngest son of the king Amyntas III and Eurydice I. In his youth, Philip was held as a hostage in Illyria under Bardylis[5] and then was held in Thebes (c. 368–365 BC), which was then the leading city of Greece. While a captive there, Philip received a military and diplomatic education from Epaminondas, became eromenos of Pelopidas,[6][7] and lived with Pammenes, who was an enthusiastic advocate of the Sacred Band of Thebes.

In 364 BC, Philip returned to Macedon. The deaths of Philip's elder brothers, King Alexander II and Perdiccas III, allowed him to take the throne in 359 BC. Originally appointed regent for his infant nephew Amyntas IV, who was the son of Perdiccas III, Philip succeeded in taking the kingdom for himself that same year.

Philip's military skills and expansionist vision of Macedonian greatness brought him early success. He first had to remedy a predicament which had been greatly worsened by the defeat against the Illyrians in which King Perdiccas himself had died. The Paionians and the Thracians had sacked and invaded the eastern regions of Macedonia, while the Athenians had landed, at Methoni on the coast, a contingent under a Macedonian pretender called Argeus.

Early military career

Using diplomacy, Philip pushed back the Paionians and Thracians promising tributes, and crushed the 3,000 Athenian hoplites (359). Momentarily free from his opponents, he concentrated on strengthening his internal position and, above all, his army. His most important innovation was doubtless the introduction of the phalanx infantry corps, armed with the famous sarissa, an exceedingly long spear, at the time the most important army corps in Macedonia.

Philip had married Audata, great-granddaughter of the Illyrian king of Dardania, Bardyllis. However, this did not prevent him from marching against the Illyrians in 358 and crushing them in a ferocious battle in which some 7,000 Illyrians died (357). By this move, Philip established his authority inland as far as Lake Ohrid and earned the favour of the Epirotes.[8]

The Athenians had been unable to conquer Amphipolis, which commanded the gold mines of Mount Pangaion. So Philip reached an agreement with Athens to lease the city to them after its conquest, in exchange for Pydna (lost by Macedon in 363). However, after conquering Amphipolis, Philip kept both cities (357). As Athens had declared war against him, he allied Macedon with the Chalkidian League of Olynthus. He subsequently conquered Potidaea, this time keeping his word and ceding it to the League in 356.

In 357 BC, Philip married the Epirote princess Olympias, who was the daughter of the king of the Molossians. Alexander was born in 356, the same year as Philip's racehorse won at the Olympic Games.

During 356 BC, Philip conquered the town of Crenides and changed its name to Philippi. He then established a powerful garrison there to control its mines, which yielded much of the gold he later used for his campaigns. In the meantime, his general Parmenion defeated the Illyrians again.

In 355–354 he besieged Methone, the last city on the Thermaic Gulf controlled by Athens. During the siege, Philip was injured in his right eye, which was later removed surgically.[9] Despite the arrival of two Athenian fleets, the city fell in 354. Philip also attacked Abdera and Maronea, on the Thracian coast (354–353).[10]

Third Sacred War

Philip was involved in the Third Sacred War which had begun in Greece in 356. In summer 353 he invaded Thessaly, defeating 7,000 Phocians under the brother of Onomarchus. The latter however defeated Philip in the two succeeding battles. Philip returned to Thessaly the next summer, this time with an army of 20,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry including all Thessalian troops. In the Battle of Crocus Field 6,000 Phocians fell, while 3,000 were taken as prisoners and later drowned.

This battle earned Philip immense prestige, as well as the free acquisition of Pherae. Philip was also tagus of Thessaly, and he claimed as his own Magnesia, with the important harbour of Pagasae.[10] Philip did not attempt to advance into Central Greece because the Athenians, unable to arrive in time to defend Pagasae, had occupied Thermopylae.

There were no hostilities with Athens yet, but Athens was threatened by the Macedonian party which Philip's gold created in Euboea. From 352 to 346 BC, Philip did not again travel south. He was active in completing the subjugation of the Balkan hill-country to the west and north, and in reducing the Greek cities of the coast as far as the Hebrus. To the chief of these coastal cities, Olynthus, Philip continued to profess friendship until its neighbouring cities were in his hands.[10]

In 349 BC, Philip started the siege of Olynthus, which, apart from its strategic position, housed his relatives Arrhidaeus and Menelaus, pretenders to the Macedonian throne. Olynthus had at first allied itself with Philip, but later shifted its allegiance to Athens. The latter, however, did nothing to help the city, its expeditions held back by a revolt in Euboea (probably paid for by Philip's gold). The Macedonian king finally took Olynthus in 348 BC and razed the city to the ground. The same fate was inflicted on other cities of the Chalcidian peninsula.

Macedon and the regions adjoining it having now been securely consolidated, Philip celebrated his Olympic Games at Dium. In 347 BC, Philip advanced to the conquest of the eastern districts about Hebrus, and compelled the submission of the Thracian prince Cersobleptes. In 346 BC, he intervened effectively in the war between Thebes and the Phocians, but his wars with Athens continued intermittently. However, Athens had made overtures for peace, and when Philip again moved south, peace was sworn in Thessaly.[10]

Later campaigns (346–336 BC)

With key Greek city-states in submission, Philip II turned to Sparta; he sent them a message: "If I win this war, you will be slaves forever." In another version, he warned: "You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city." According to both accounts, the Spartans' laconic reply was one word: "If." Philip II and Alexander both chose to leave Sparta alone. Later, Macedonian arms were carried across Epirus to the Adriatic Sea.[10]

In 345 BC, Philip conducted a hard-fought campaign against the Ardiaioi (Ardiaei), under their king Pleuratus I, during which Philip was seriously wounded in the lower right leg by an Ardian soldier.[11]

In 342 BC, Philip led a great military expedition north against the Scythians, conquering the Thracian fortified settlement Eumolpia to give it his name, Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv).

In 340 BC, Philip started the siege of Perinthus, and in 339 BC, began another siege against the city of Byzantium. As both sieges failed, Philip's influence over Greece was compromised.[10] He successfully reasserted his authority in the Aegean by defeating an alliance of Thebans and Athenians at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, and in the same year, destroyed Amfissa because the residents had illegally cultivated part of the Crisaian plain which belonged to Delphi. These decisive victories led to Philip being recognized as the military leader of the League of Corinth, a Greek confederation allied against the Persian Empire, in 338/7 BC.[12][13] Members of the league agreed never to wage war against each other, unless it was to suppress revolution.[14]

Asian campaign (336 BC)

Philip II was involved quite early against the Achaemenid Empire. From around 352 BC, he supported several Persian opponents to Artaxerxes III, such as Artabazos II, Amminapes or a Persian nobleman named Sisines, by receiving them for several years as exiles at the Macedonian court.[15][16][17][18] This gave him a good knowledge of Persian issues, and may even have influenced some of his innovations in the management of the Macedonian state.[15] Alexander was also acquainted with these Persian exiles during his youth.[16][19][20]

In 336 BC, Philip II sent Parmenion, with Amyntas, Andromenes and Attalus, and an army of 10,000 men into Asia Minor to make preparations for an invasion to free the Greeks living on the western coast and islands from Achaemenid rule.[21][22] At first, all went well. The Greek cities on the western coast of Anatolia revolted until the news arrived that Philip had been assassinated and had been succeeded as king by his young son Alexander. The Macedonians were demoralized by Philip's death and were subsequently defeated near Magnesia by the Achaemenids under the command of the mercenary Memnon of Rhodes.[22][21]

Assassination

Philip was murdered in October 336 BC, at Aegae, the ancient capital of the kingdom of Macedon. The court had gathered there for the celebration of the marriage between Alexander I of Epirus and Cleopatra of Macedon, who was Philip's daughter by his fourth wife Olympias. While the king was entering unprotected into the town's theatre (highlighting his approachability to the Greek diplomats present), he was killed by Pausanias of Orestis, one of his seven bodyguards. The assassin immediately tried to escape and reach his associates who were waiting for him with horses at the entrance to Aegae. He was pursued by three of Philip's bodyguards, tripped on a vine, and died by their hands.[23]

The reasons for the assassination are difficult to expound fully: There was already controversy among ancient historians, and the only contemporary account in our possession is that of Aristotle, who states rather tersely that Philip was killed because Pausanias had been offended by the followers of Attalus, uncle of Philip's wife Cleopatra (renamed Eurydice upon marriage).

Cleitarchus' analysis

Fifty years later, the historian Cleitarchus expanded and embellished the story. Centuries later, this version was to be narrated by Diodorus Siculus and all the historians who used Cleitarchus. According to the sixteenth book of Diodorus' history,[24] Pausanias of Orestis had been a lover of Philip, but became jealous when Philip turned his attention to a younger man, also called Pausanias. The elder Pausanias' taunting of the new lover caused the younger Pausanias to throw away his life in battle, which turned his friend Attalus against the elder Pausanias. Attalus took his revenge by getting Pausanias of Orestis drunk at a public dinner and then raping him.

When Pausanias complained to Philip, the king felt unable to chastise Attalus, as he was about to send him to Asia with Parmenion, to establish a bridgehead for his planned invasion. Philip also was recently married to Attalus' niece, Cleopatra Eurydice. Rather than offend Attalus, Philip tried to mollify Pausanias by elevating him within his personal bodyguard. Pausanias' desire for revenge seems to have turned towards the man who had failed to avenge his damaged honour, so he planned to kill Philip. Some time after the alleged rape, while Attalus was away in Asia fighting the Persians, he put his plan in action.

Justin's analysis

Other historians (e.g., Justin 9.7) suggested that Alexander and/or his mother Olympias were at least privy to the intrigue, if not themselves instigators. The latter seems to have been anything but discreet in manifesting her gratitude to Pausanias, according to Justin's report: He writes that the same night of her return from exile, she placed a crown on the assassin's corpse, and later erected a tumulus over his grave and ordering annual sacrifices to the memory of Pausanias.[25]

Modern analysis

Many modern historians have observed that none of the accounts are probable: In the case of Pausanias, the stated motive of the crime hardly seems adequate. On the other hand, the implication of Alexander and Olympias seems specious – to act as they did would have required brazen effrontery in the face of a military personally loyal to Philip. What seems to be recorded are the natural suspicions that fell on the chief beneficiaries of the assassination, however their actions in response to the murder cannot prove their guilt in the crime itself – regardless of how sympathetic they might have seemed afterward.

Whatever the actual background to the assassination, it may have had an enormous effect on later world history, far beyond what any conspirators could have predicted. As asserted by some modern historians, had the older and more settled Philip been the one in charge of the war against Persia, he might have rested content with relatively moderate conquests, e.g., making Anatolia into a Macedonian province, and not pushed further into an overall conquest of Persia and further campaigns in India.

Marriages

The dates of Philip's multiple marriages and the names of some of his wives are contested. Below is the order of marriages offered by Athenaeus, 13.557b–e:

- Audata, the daughter of Illyrian king Bardyllis. Mother of Cynane.

- Phila of Elimeia, the sister of Derdas and Machatas of Elimiotis.

- Nicesipolis of Pherae, Thessaly, mother of Thessalonica.

- Olympias of Epirus, mother of Alexander the Great and Cleopatra.

- Philinna of Larissa, mother of Arrhidaeus later called Philip III of Macedon.

- Meda of Odessos, daughter of the king Cothelas, of Thrace.

- Cleopatra, daughter of Hippostratus and niece of general Attalus of Macedonia. Philip renamed her Cleopatra Eurydice of Macedon.

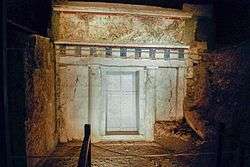

Tomb of Philip II at Aigai

In 1977, Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos started excavating the Great Tumulus at Aigai[26] near modern Vergina, the capital and burial site of the kings of Macedon, and found that two of the four tombs in the tumulus were undisturbed since antiquity. Moreover, these two, and particularly Tomb II, contained fabulous treasures and objects of great quality and sophistication.[27]

Although there was much debate for some years,[28] as suspected at the time of the discovery Tomb II has been shown to be that of Philip II as indicated by many features, including the greaves, one of which was shaped consistently to fit a leg with a misaligned tibia (Philip II was recorded as having broken his tibia). Also, the remains of the skull show damage to the right eye caused by the penetration of an object (historically recorded to be an arrow).[29][30]

A study of the bones published in 2015 indicates that Philip was buried in Tomb I, not Tomb II.[31] On the basis of age, knee ankylosis, and a hole matching the penetrating wound and lameness suffered by Philip, the authors of the study identified the remains of Tomb I in Vergina as those of Philip II.[31] Tomb II instead was identified in the study as that of King Arrhidaeus and his wife Eurydice II.[31] However, this latter theory had previously been shown to be false.[30]

More recent research gives further evidence that Tomb II contains the remains of Philip II.[32]

Great Tumulus of Aigai

Great Tumulus of Aigai The tomb of Philip II of Macedon at the Museum of the Royal Tombs in Vergina

The tomb of Philip II of Macedon at the Museum of the Royal Tombs in Vergina The golden larnax and the golden grave crown of Philip

The golden larnax and the golden grave crown of Philip

Legacy

Cult

The heroon at Vergina in Macedonia (the ancient city of Aegae – Αἰγαί) is thought to have been dedicated to the worship of the family of Alexander the Great and may have housed the cult statue of Philip. It is probable that he was regarded as a hero or deified on his death. Though the Macedonians did not consider Philip a god, he did receive other forms of recognition from the Greeks, e.g. at Eresos (altar to Zeus Philippeios), Ephesos (his statue was placed in the temple of Artemis), and at Olympia, where the Philippeion was built.

Isocrates once wrote to Philip that if he defeated Persia, there would be nothing left for him to do but to become a god,[33] and Demades proposed that Philip be regarded as the thirteenth god; however, there is no clear evidence that Philip was raised to the divine status accorded his son Alexander.[34]

Fictional portrayals

- Fredric March portrayed Philip II of Macedon in the film Alexander the Great (1956).

- Val Kilmer portrayed Philip II of Macedon in Oliver Stone's 2004 biopic Alexander.

- Sunny Ghanshani portrayed Philip II of Macedon in Siddharth Kumar Tewary's series Porus.

Games

- Hegemony Gold: Wars of Ancient Greece is a PC strategy game that follows the campaigns of Philip II in Greece.

- Philip II appears in the Battle of Chaeronea in Rome: Total War: Alexander

Dedications

- Filippos Veria, one of the most successful handball teams of Greece, bears the name of Philip II. He is also depicted in the team's emblem.

- Philip II is depicted in the emblem of the 2nd Support Brigade of the Hellenic Army, stationed in Kozani.[35]

References

- Pohlenz, Max (1966). Freedom in Greek life and thought: the history of an ideal. Springer. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-277-0009-4.

- Worthington, Ian. 2008. Philip II of Macedonia. New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 0300164769, 9780300164763

- Cosmopoulos, Michael B. 1992. Macedonia: An Introduction to its Political History. Winnipeg: Manitoba Studies in Classical Civilization, p. 30 (TABLE 2: The Argeiad Kings).

- Diodorus Sicilus, Book 16, 89.[3] «διόπερ ἐν Κορίνθῳ τοῦ κοινοῦ συνεδρίου συναχθέντος διαλεχθεὶς περὶ τοῦ πρὸς Πέρσας πολέμου καὶ μεγάλας ἐλπίδας ὑποθεὶς προετρέψατο τοὺς συνέδρους εἰς πόλεμον. τέλος δὲ τῶν Ἑλλήνων ἑλομένων αὐτὸν στρατηγὸν αὐτοκράτορα τῆς Ἑλλάδος μεγάλας παρασκευὰς ἐποιεῖτο πρὸς τὴν ἐπὶ τοὺς Πέρσας στρατείαν...καὶ τὰ μὲν περὶ Φίλιππον ἐν τούτοις ἦν»

- Howe, T. (2017), "Plain tales from the hills: Illyrian influences on Argead military development", in S. Müller, T. Howe, H. Bowden and R. Rollinger (eds.), The History of the Argeads: New Perspectives. Wiesbaden, 99-113.

- Dio Chrysostom Or. 49.5

- Murray, Stephen O. Homosexualities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, page 42

- The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC by D. M. Lewis, 1994, p. 374, ISBN 0-521-23348-8: "... The victory over Bardylis made him an attractive ally to the Epirotes, who too had suffered at the Illyrians' hands, and his recent alignment ..."

- A special instrument known as the Spoon of Dioclese was used to remove his eye.

-

- Ashley, James R., The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359–323 BCE., McFarland, 2004, p. 114, ISBN 0-7864-1918-0

- Cawkwell, George (1978). Philip II of Macedon. London, United Kingdom: Faber & Faber. p. 170. ISBN 0-571-10958-6.

- Wells, H. G. (1961) [1937]. The Outline of History: Volume 1. Doubleday. pp. 279–80.

... in 338 B.C. a congress of Greek states recognized him as captain-general for the war against Persia.

- Rhodes, Peter John; Osborne, Robin (2003). Greek Historical Inscriptions: 404–323 BC. Oxford University Press. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-19-815313-9.

- Morgan, Janett (2016). Greek Perspectives on the Achaemenid Empire: Persia Through the Looking Glass. Edinburgh University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-7486-4724-8.

- Cawthorne, Nigel (2004). Alexander the Great. Haus Publishing. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-904341-56-7.

- Briant, Pierre (2012). Alexander the Great and His Empire: A Short Introduction. Princeton University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-691-15445-9.

- Jensen, Erik (2018). Barbarians in the Greek and Roman World. Hackett Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-62466-714-5.

- Howe, Timothy; Brice, Lee L. (2015). Brill's Companion to Insurgency and Terrorism in the Ancient Mediterranean. BRILL. p. 170. ISBN 978-90-04-28473-9.

- Carney, Elizabeth Donnelly (2000). Women and Monarchy in Macedonia. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8061-3212-9.

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 817. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

- Heckel, Waldemar (2008). Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire. John Wiley & Sons. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-4051-5469-7.

- Wells, H. G. (1961) [1937]. The Outline of History: Volume 1. Doubleday. p. 282.

The murderer had a horse waiting, and would have got away, but the foot of his horse caught in a wild vine, and he was thrown from the saddle by the stumble, and slain by his pursuers.

- Diodorus Siculus. "The Library of History". 16.91-95. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010.

- Marcus Junianus, Justinus (1768). "9.7". Justini historiæPhilippicæ: Cum versionse anglica, ad verbum, quantum fieri potuit, facta, or, The history of Justin; with an English translation, as literal as possible. By John Clarke, author of the essays upon education and study. Translated by Clarke, John (6th ed.). London, U.K.: Printed for L. Hawes, W. Clarke, and R. Collins, in Pater-Noster Row, M.DCC.LXVIII. pp. 89–90.

- "Αιγές (Βεργίνα) | Museum of Royal Tombs of Aigai -Vergina".

- National Geographic article outlining recent archaeological examinations of Tomb II.

- Hatzopoulos B. Miltiades, The Burial of the Dead (at Vergina) or The Unending Controversy on the Identity of the Occupant of Tomb II. Tekmiria, vol. 9 (2008) Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- See John Prag and Richard Neave's report in Making Faces: Using Forensic and Archaeological Evidence, published for the Trustees of the British Museum by the British Museum Press, London: 1997.

- Musgrave J, Prag A. J. N. W., Neave R., Lane Fox R., White H. (2010) The Occupants of Tomb II at Vergina. Why Arrhidaios and Eurydice must be excluded, Int J Med Sci 2010; 7:s1–s15

- Antonis Bartsiokas; et al. (20 July 2015). "The lameness of King Philip II and Royal Tomb I at Vergina, Macedonia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (32): 9844–48. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.9844B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1510906112. PMC 4538655. PMID 26195763.

- New Finds from the Cremains in Tomb II at Aegae Point to Philip II and a Scythian Princess, T. G. Antikas* and L. K. Wynn-Antikas, International Journal of Osteoarchaeology

- Backgrounds of early Christianity By Everett Ferguson p. 202 ISBN 0-8028-0669-4

- The twelve gods of Greece and Rome By Charlotte R. Long p. 207 ISBN 90-04-07716-2

- "Γενικό Επιτελείο Στρατού: Εμβλήματα Όπλων και Σωμάτων". Hellenic Army General Staff. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philip II of Macedon. |

- A family tree focusing on his ancestors

- A family tree focusing on his descendants

- Plutarch: Life of Alexander

- Pothos.org, Death of Philip: Murder or Assassination?

- Philip II of Macedon entry in historical source book by Mahlon H. Smith

- Facial reconstruction expert revealed how technique brings past to life, press release of the University of Leicester, with a portrait of Philip based on a reconstruction of his face.

- Twilight of the Polis and the rise of Macedon (Philip, Demosthenes and the Fall of the Polis). Yale University courses, Lecture 24. (Introduction to Ancient Greek History)

- The Burial of the Dead (at Vergina) or The Unending Controversy on the Identity of the Occupants of Tomb II

Philip II of Macedon Born: 382 BC Died: 336 BC | ||

| Preceded by Perdiccas III |

King of Macedon 359–336 BC |

Succeeded by Alexander III the Great |

.jpg)

_Pentathlon.svg.png)