Little owl

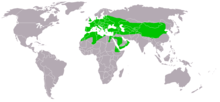

The little owl (Athene noctua) is a bird that inhabits much of the temperate and warmer parts of Europe, the Palearctic east to Korea, and north Africa. It was introduced into Britain at the end of the nineteenth century and into the South Island of New Zealand in the early twentieth century.

| Little owl | |

|---|---|

(1).jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Strigidae |

| Genus: | Athene |

| Species: | A. noctua |

| Binomial name | |

| Athene noctua (Scopoli, 1769) | |

| |

| Range of the little owl | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carine noctua | |

This owl is a member of the typical or true owl family, Strigidae, which contains most species of owl, the other grouping being the barn owls, Tytonidae. It is a small, cryptically coloured, mainly nocturnal species and is found in a range of habitats including farmland, woodland fringes, steppes and semi-deserts. It feeds on insects, earthworms, other invertebrates and small vertebrates. Males hold territories which they defend against intruders. This owl is a cavity nester and a clutch of about four eggs is laid in spring. The female does the incubation and the male brings food to the nest, first for the female and later for the newly hatched young. As the chicks grow, both parents hunt and bring them food, and the chicks leave the nest at about seven weeks of age.

Being a common species with a wide range and large total population, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed its conservation status as "least concern".

Description

The little owl is a small owl with a flat-topped head, a plump, compact body and a short tail. The facial disc is flattened above the eyes giving the bird a frowning expression. The plumage is greyish-brown, spotted, streaked and barred with white. The underparts are pale and streaked with darker colour.[2] It is usually 22 centimetres (8.7 in) in length with a wingspan of 56 centimetres (22 in) for both sexes, and weighs about 180 grams (6.3 oz).[3]

The adult little owl of the most widespread form, the nominate A. n. noctua, is white-speckled brown above, and brown-streaked white below. It has a large head, long legs, and yellow eyes, and its white “eyebrows” give it a stern expression. Juveniles are duller, and lack the adult's white crown spots. This species has a bounding flight like a woodpecker.[2] Moult begins in July and continues to November, with male starting before female.

The call is a querulous kiew, kiew. Less frequently, various whistling or trilling calls are uttered. In the breeding season, other more modulated calls are made, and a pair may call in duet. Various yelping, chattering or barking sounds are made in the vicinity of the nest.[2]

Distribution and habitat

The distribution is widespread across Europe, Asia and North Africa. Its range in Eurasia extends from the Iberian Peninsula and Denmark eastwards to China and southwards to the Himalayas. In Africa it is present from Mauritania to Egypt, the Red Sea and Arabia. The bird has been introduced to New Zealand, and to the United Kingdom, where it has spread across much of England and the whole of Wales.[4]

This is a sedentary species which is found in open countryside in a great range of habitats. These include agricultural land with hedgerows and trees, orchards, woodland verges, parks and gardens, as well as steppes and stony semi-deserts. It is also present in treeless areas such as dunes, and in the vicinity of ruins, quarries and rocky outcrops. It sometimes ventures into villages and suburbs. In the United Kingdom it is chiefly a bird of the lowlands, and usually occurs below 500 m (1,600 ft).[2] In continental Europe and Asia it may be found at much higher elevations; one individual was recorded from 3,600 m (12,000 ft) in Tibet.[5]

Behaviour and ecology

This owl usually perches in an elevated position ready to swoop down on any small creature it notices. It feeds on prey such as insects and earthworms, as well as small vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. It may pursue prey on the ground and it caches surplus food in holes or other hiding places.[4] A study of the pellets of indigestible material that the birds regurgitate found mammals formed 20 to 50% of the diet and insects 24 to 49%. Mammals taken included mice, rats, voles, shrews, moles and rabbits. The birds were mostly taken during the breeding season and were often fledglings, and including the chicks of game birds. The insects included Diptera, Dermaptera, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera. Some vegetable matter (up to 5%) was included in the diet and may have been ingested incidentally.[2]

.jpg)

The little owl is territorial, the male normally remaining in one territory for life. However the boundaries may expand and contract, being largest in the courtship season in spring. The home range, in which the bird actually hunts for food, varies with the type of habitat and time of year. Little owls with home-ranges that incorporate a high diversity of habitats are much smaller (< 2 ha) than those which breed in monotonous farmland (with home-ranges over 12 ha). Larger home ranges results in increased flight activity, longer foraging trips and fewer nest visits.[6] If a male intrudes into the territory of another, the occupier approaches and emits its territorial calls. If the intruder persists, the occupier flies at him aggressively. If this is unsuccessful, the occupier repeats the attack, this time trying to make contact with his claws. In retreat, an owl often drops to the ground and makes a low-level escape.[7] The territory is more actively defended against a strange male as compared to a known male from a neighbouring territory; it has been shown that the little owl can recognise familiar birds by voice.[8]

This owl becomes more vocal at night as the breeding season approaches in late spring. The nesting location varies with habitat, nests being found in holes in trees, in cliffs, quarries, walls, old buildings, river banks and rabbit burrows.[5] A clutch of three to five eggs is laid (occasionally two to eight). The eggs are broadly elliptical, white and without gloss; they measure about 35.5 by 29.5 mm (1.40 by 1.16 in). They are incubated by the female who sometimes starts sitting after the first egg is laid. While she is incubating the eggs, the male brings food for her. The eggs hatch after twenty-eight or twenty-nine days.[2] At first the chicks are brooded by the female and the male brings in food which she distributes to them. Later, both parents are involved in hunting and feeding them. The young leave the nest at about seven weeks, and can fly a week or two later. Usually there is a single brood but when food is abundant, there may be two.[4] The energy reserves that little owl chicks are able to build up when in the nest influences their post-fledgling survival, with birds in good physical condition having a much higher chance of survival than those in poor condition.[9] When the young disperse, they seldom travel more than about 20 kilometres (12 mi).[10] Pairs of birds often remain together all year round and the bond may last until one partner dies.[10]

The little owl is partly diurnal and often perches boldly and prominently during the day.[5] If living in an area with a large amount of human activity, little owls may grow used to humans and will remain on their perch, often in full view, while people are around. The little owl has a life expectancy of about sixteen years.[4] However, many birds do not reach maturity; severe winters can take their toll and some birds are killed by road vehicles at night,[4] so the average lifespan may be on the order of three years.[3]

Status

A. noctua has an extremely large range. It has been estimated that there are between 560 thousand and 1.3 million breeding pairs in Europe, and as Europe equates to 25 to 49% of the global range, the world population may be between 5 million and 15 million birds. The population is believed to be stable, and for these reasons, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed the bird's conservation status as being of "least concern".[1]

In human culture

Owls have often been depicted from the Upper Palaeolithic onwards, in forms from statuettes and drawings to pottery and wooden posts, but in the main they are generic rather than identifiable to species. The little owl is, however, closely associated with the Greek goddess Athena and the Roman goddess Minerva, and hence represents wisdom and knowledge. A little owl with an olive branch appears on a Greek tetradrachm coin from 500 BC (a copy of which appears on the modern Greek one-euro coin) and in a 5th-century B.C. bronze statue of Athena holding the bird in her hand. The call of a little owl was thought to have heralded the murder of Julius Caesar.[11][12] The genus name, Athene, commemorates the goddess, whose original role as a goddess of the night might explain the link to an owl. The species name noctua has, in effect, the same meaning, being the Latin name of an owl sacred to Minerva, Athena's Roman counterpart.[13]

In Romanian folklore, the little owl is said to be a harbinger of death.[14] In 1992, the little owl appeared as a watermark on Jaap Drupsteen’s 100 guilder banknote for the Netherlands.[15]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Athene noctua". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T22689328A40420964. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22689328A40420964.en.

- Witherby, H. F., ed. (1943). Handbook of British Birds, Volume 2: Warblers to Owls. H. F. and G. Witherby Ltd. pp. 26–27.

- "Little Owl (Athene noctua)". British Trust for Ornithology. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Lewis, Deane (9 August 2013). "Little Owl: Athene noctua". The Owl Pages. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- Baker, ECS (1927). Fauna of British India. Birds. 4 (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 441–443.

- Staggenborg, J.; Schaefer, H. M.; Stange, C.; Naef-Daenzer, B.; Grüebler, M. U. (2017). "Time and travelling costs during chick-rearing in relation to habitat quality in Little Owls Athene noctua". Ibis. 159 (3): 519–531. doi:10.1111/ibi.12465.

- Finck, Peter (1990). "Seasonal variation of territory size with the little owl (Athene noctua)". Oecologia. 83 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1007/BF00324636. PMID 28313245.

- Hardouin, Loïc A.; Tabel, Pierre; Bretagnolle, Vincent (2006). "Neighbour–stranger discrimination in the little owl, Athene noctua". Animal Behaviour. 72 (1): 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.09.020.

- Perrig, M.; Grüebler, M. U.; Keil, H.; Naef-Daenzer, B. (2017). "Post-fledging survival of Little Owls Athene noctua in relation to nestling food supply". Ibis. 159 (3): 519–531. doi:10.1111/ibi.12477.

- Holt, D.W.; Berkley, R.; Deppe, C.; Enríquez Rocha, P.; Petersen, J.L.; Rangel Salazar, J.L.; Segars, K.P.; Wood, K.L.; Kirwan, G.M.; Christie, D.A. (2014). "Little owl: Athene noctua". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- Van Nieuwenhuyse, Dries; Genot, Jean-Claude; Johnson, David H. (2008). The Little Owl: Conservation, Ecology and Behavior of Athene noctua. Cambridge University Press. pp. Chapter 2. ISBN 978-0-521-71420-4.

- Eason, Cassandra (2008). Fabulous Creatures, Mythical Monsters, and Animal Power Symbols: A Handbook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-275-99425-9.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 58, 274. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Pasarile prevestitoare Cultura. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- "Overzicht in te wisselen biljetten". De Nederlandsche Bank. Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Athene noctua. |