Brooklyn

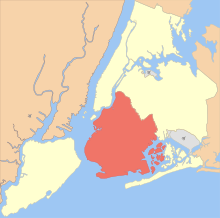

Brooklyn (/ˈbrʊklɪn/) is a borough of New York City, coterminous with Kings County, located in the U.S. state of New York. It is the most populous county in the state, the second-most densely populated county in the United States,[5] and New York City's most populous borough, with an estimated 2,648,403 residents in 2020.[6] Named after the Dutch village of Breukelen, it shares a land border with the borough of Queens at the western end of Long Island. Brooklyn has several bridge and tunnel connections to the borough of Manhattan across the East River, and the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge connects it with Staten Island.

Brooklyn Kings County, New York | |

|---|---|

Borough and county | |

Clockwise from top left: Brooklyn Bridge, Brooklyn brownstones, Soldiers' and Sailors' Arch, Brooklyn Borough Hall, Coney Island | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Motto(s): | |

Interactive map outlining Brooklyn | |

Location within the state of New York | |

| Coordinates: 40°37′29″N 73°57′8″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Kings (coterminous) |

| City | New York City |

| Settled | 1634 |

| Named for | Breukelen, Netherlands |

| Government | |

| • Type | Borough |

| • Borough President | Eric Adams (D) — (Borough of Brooklyn) |

| • District Attorney | Eric Gonzalez (D) — (Kings County) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 97 sq mi (250 km2) |

| • Land | 70.82 sq mi (183.4 km2) |

| • Water | 26 sq mi (70 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 2,504,701[1] |

| • Estimate (2019) | 2,559,903 |

| • Density | 35,367.1/sq mi (13,655.3/km2) |

| • Demonym | Brooklynite[2] |

| ZIP Code prefix | 112 |

| Area codes | 718/347/929, 917 |

| GDP (2018) | US$91.6 billion[3] |

| Website | www |

With a land area of 70.82 square miles (183.4 km2) and water area of 26 square miles (67 km2), Kings County is New York state's fourth-smallest county by land area and third-smallest by total area, though it is the second-largest among the city's five boroughs in terms of area and largest in terms of population.[7] If each borough were ranked as a city, Brooklyn would rank as the third-most populous in the U.S., after Los Angeles and Chicago.

Brooklyn was an independent incorporated city (and previously an authorized village and town within the provisions of the New York State Constitution) until January 1, 1898, when, after a long political campaign and public relations battle during the 1890s, according to the new Municipal Charter of "Greater New York", Brooklyn was consolidated with the other cities, boroughs, and counties to form the modern City of New York, surrounding the Upper New York Bay with five constituent boroughs. The borough continues, however, to maintain a distinct culture. Many Brooklyn neighborhoods are ethnic enclaves. Brooklyn's official motto, displayed on the Borough seal and flag, is Eendraght Maeckt Maght, which translates from early modern Dutch as "Unity makes strength".

In the first decades of the 21st century, Brooklyn has experienced a renaissance as an avant-garde destination for hipsters,[8] with concomitant gentrification, dramatic house price increases and a decrease in housing affordability.[9] Since the 2010s, Brooklyn has evolved into a thriving hub of entrepreneurship, high technology startup firms,[10][11] postmodern art[12] and design.[11]

New York City's five boroughs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jurisdiction | Population | Gross Domestic Product | Land area | Density | ||||

| Borough | County | Estimate (2019)[13] | billions (US$)[14] | per capita (US$) | square miles | square km | persons / sq. mi | persons / km2 |

Bronx |

1,418,207 | 42.695 | 30,100 | 42.10 | 109.04 | 33,867 | 13,006 | |

Kings |

2,559,903 | 91.559 | 35,800 | 70.82 | 183.42 | 36,147 | 13,957 | |

New York |

1,628,706 | 600.244 | 368,500 | 22.83 | 59.13 | 71,341 | 27,544 | |

Queens |

2,253,858 | 93.310 | 41,400 | 108.53 | 281.09 | 20,767 | 8,018 | |

Richmond |

476,143 | 14.514 | 30,500 | 58.37 | 151.18 | 8,157 | 3,150 | |

| 8,336,817 | 842.343 | 101,000 | 302.64 | 783.83 | 27,547 | 10,636 | ||

| 19,453,561 | 1,731.910 | 89,000 | 47,126.40 | 122,056.82 | 412 | 159 | ||

Sources:[15] and see individual borough articles | ||||||||

Etymology

The name Brooklyn is derived from the original Dutch colonial name Breuckelen. The oldest mention of the settlement in the Netherlands, is in a charter of 953 of Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, namely Broecklede.[16] This is a composition of the two words broeck, meaning bog or marshland and lede, meaning small (dug) water stream specifically in peat areas.[17] Breuckelen in the American continent is established in 1646, the name first appeared in print in 1663.[18] The Dutch colonists named it after the scenic town of Breukelen, Netherlands.[19][20] Over the past two millennia, the name of the ancient town in Holland has been Bracola, Broccke, Brocckede, Broiclede, Brocklandia, Broekclen, Broikelen, Breuckelen and finally Breukelen.[21] The New Amsterdam settlement of Breuckelen also went through many spelling variations, including Breucklyn, Breuckland, Brucklyn, Broucklyn, Brookland, Brockland, Brocklin, and Brookline/Brook-line. There have been so many variations of the name that its origin has been debated; some have claimed breuckelen means "broken land".[22] The final name of Brooklyn, however, is the most accurate to its meaning.[23][24]

History

The history of European settlement in Brooklyn spans more than 350 years. The settlement began in the 17th century as the small Dutch-founded town of "Breuckelen" on the East River shore of Long Island, grew to be a sizeable city in the 19th century, and was consolidated in 1898 with New York City (then confined to Manhattan and part of the Bronx), the remaining rural areas of Kings County, and the largely rural areas of Queens and Staten Island, to form the modern City of New York.

Colonial era

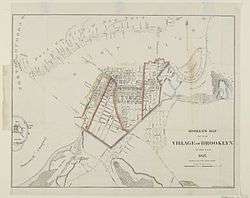

Six Dutch towns

The Dutch were the first Europeans to settle Long Island's western edge, which was then largely inhabited by the Lenape, an Algonquian-speaking American Indian tribe often referred to in colonial documents by a variation of the place name "Canarsie". Bands were associated with place names, but the colonists thought their names represented different tribes. The Breuckelen settlement was named after Breukelen in the Netherlands; it was part of New Netherland. The Dutch West India Company lost little time in chartering the six original parishes (listed here by their later English town names):[25]

- Gravesend: in 1645, settled under Dutch patent by English followers of Anabaptist Deborah Moody, named for 's-Gravenzande, Netherlands, or Gravesend, England

- Brooklyn Heights: as Breuckelen in 1646, after the town now spelled Breukelen, Netherlands. Breuckelen was along Fulton Street (now Fulton Mall) between Hoyt Street and Smith Street (according to H. Stiles and P. Ross). Brooklyn Heights, or Clover Hill, is where the village of Brooklyn was founded in 1816.

- Flatlands: as Nieuw Amersfoort in 1647

- Flatbush: as Midwout in 1652

- Nieuw Utrecht: in 1657, after the city of Utrecht, Netherlands

- Bushwick: as Boswijck in 1661

The colony's capital of New Amsterdam, across the East River, obtained its charter in 1653, later than the village of Brooklyn. The neighborhood of Marine Park was home to North America's first tide mill. It was built by the Dutch, and the foundation can be seen today. But the area was not formally settled as a town. Many incidents and documents relating to this period are in Gabriel Furman's 1824 compilation.[26]

Six townships in an English province

What is now Brooklyn today left Dutch hands after the final English conquest of New Netherland in 1664, a prelude to the Second Anglo-Dutch War. New Netherland was taken in a naval action, and the conquerors renamed their prize for the overall English naval commander, James, Duke of York, brother of the then monarch King Charles II of England and future king himself as King James II of England and James VII of Scotland; Brooklyn became a part of the new English and later British colony, the Province of New York.

The English reorganized the six old Dutch towns on southwestern Long Island as Kings County on November 1, 1683,[27] one of the "original twelve counties" then established in New York Province. This tract of land was recognized as a political entity for the first time, and the municipal groundwork was laid for a later expansive idea of Brooklyn identity.

Lacking the patroon and tenant farmer system established along the Hudson River Valley, this agricultural county unusually came to have one of the highest percentages of slavery among the population in the "Original Thirteen Colonies" along the Atlantic Ocean eastern coast of North America.[28]

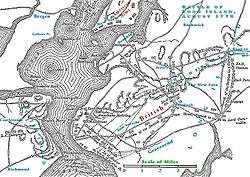

Revolutionary War

On August 27, 1776, was fought the Battle of Long Island (also known as the 'Battle of Brooklyn'), the first major engagement fought in the American Revolutionary War after independence was declared, and the largest of the entire conflict. British troops forced Continental Army troops under George Washington off the heights near the modern sites of Green-Wood Cemetery, Prospect Park, and Grand Army Plaza.[29]

Washington, viewing particularly fierce fighting at the Gowanus Creek from atop a hill near the west end of present-day Atlantic Avenue, was famously reported to have emotionally exclaimed: "What brave men I must this day lose!".[29]

The fortified American positions at Brooklyn Heights consequently became untenable and were evacuated a few days later, leaving the British in control of New York Harbor. While Washington's defeat on the battlefield cast early doubts on his ability as the commander, the tactical withdrawal of all his troops and supplies across the East River in a single night is now seen by historians as one of his most brilliant triumphs.[29]

The British controlled the surrounding region for the duration of the war, as New York City was soon occupied and became their military and political base of operations in North America for the remainder of the conflict. The British generally enjoyed a dominant Loyalist sentiment from the residents in Kings County who did not evacuate, though the region was also the center of the fledgling—and largely successful—American intelligence network, headed by Washington himself.

The British set up a system of notorious prison ships off the coast of Brooklyn in Wallabout Bay, where more American patriots died of intentional neglect than died in combat on all the battlefields of the American Revolutionary War, combined. One result of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 was the evacuation of the British from New York City, celebrated by residents into the 20th century.

Post-colonial era

Urbanization

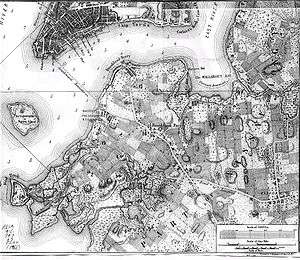

The first half of the 19th century saw the beginning of the development of urban areas on the economically strategic East River shore of Kings County, facing the adolescent City of New York confined to Manhattan Island. The New York Navy Yard operated in Wallabout Bay (border between Brooklyn and Williamsburgh) during the 19th century and two-thirds of the 20th century.

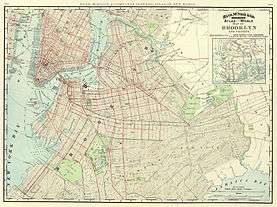

The first center of urbanization sprang up in the Town of Brooklyn, directly across from Lower Manhattan, which saw the incorporation of the Village of Brooklyn in 1817. Reliable steam ferry service across the East River to Fulton Landing converted Brooklyn Heights into a commuter town for Wall Street. Ferry Road to Jamaica Pass became Fulton Street to East New York. Town and Village were combined to form the first, kernel incarnation of the City of Brooklyn in 1834.

In a parallel development, the Town of Bushwick, farther up the river, saw the incorporation of the Village of Williamsburgh in 1827, which separated as the Town of Williamsburgh in 1840 and formed the short-lived City of Williamsburgh in 1851. Industrial deconcentration in the mid-century was bringing shipbuilding and other manufacturing to the northern part of the county. Each of the two cities and six towns in Kings County remained independent municipalities and purposely created non-aligning street grids with different naming systems.

However, the East River shore was growing too fast for the three-year-old infant City of Williamsburgh; it, along with its Town of Bushwick hinterland, was subsumed within a greater City of Brooklyn in 1854.

By 1841, with the appearance of The Brooklyn Eagle, and Kings County Democrat published by Alfred G. Stevens, the growing city across the East River from Manhattan was producing its own prominent newspaper.[30] It later became the most popular and highest circulation afternoon paper in America. The publisher changed to L. Van Anden on April 19, 1842,[31] and the paper was renamed The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and Kings County Democrat on June 1, 1846.[32] On May 14, 1849, the name was shortened to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle;[33] on September 5, 1938, it was further shortened to Brooklyn Eagle.[34] The establishment of the paper in the 1840s helped develop a separate identity for Brooklynites over the next century. The borough's soon-to-be-famous National League baseball team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, also assisted with this. Both major institutions were lost in the 1950s: the paper closed in 1955 after unsuccessful attempts at a sale following a reporters' strike, and the baseball team decamped for Los Angeles in a realignment of major league baseball in 1957.

Agitation against Southern slavery was stronger in Brooklyn than in New York,[35] and under Republican leadership, the city was fervent in the Union cause in the Civil War. After the war the Henry Ward Beecher Monument was built downtown to honor a famous local abolitionist. A great victory arch was built at what was then the south end of town to celebrate the armed forces; this place is now called Grand Army Plaza.

The number of people living in Brooklyn grew rapidly early in the 19th century. There were 4,402 by 1810, 7,175 in 1830 and 15,396 by 1830.[36] The city's population was 25,000 in 1834, but the police department comprised only 12 men on the day shift and another 12 on the night shift. Every time a rash of burglaries broke out, officials blamed burglars from New York City. Finally, in 1855, a modern police force was created, employing 150 men. Voters complained of inadequate protection and excessive costs. In 1857, the state legislature merged the Brooklyn force with that of New York City.[37]

Civil War

Fervent in the Union cause, the city of Brooklyn played a major role in supplying troops and materiel for the American Civil War. The most well-known regiment to be sent off to war from the city was the 14th Brooklyn "Red Legged Devils". They fought from 1861 to 1864, wore red the entire war, and were the only regiment named after a city. President Lincoln called them into service, making them part of a handful of three-year enlisted soldiers in April 1861. Unlike other regiments during the American Civil War, the 14th wore a uniform inspired by the French Chasseurs, a light infantry used for quick assaults.

As a seaport and a manufacturing center, Brooklyn was well prepared to contribute to the Union's strengths in shipping and manufacturing. The two combined in shipbuilding; the ironclad Monitor was built in Brooklyn.

Twin city

Brooklyn is referred to as the twin city of New York in the 1883 poem, "The New Colossus" by Emma Lazarus, which appears on a plaque inside the Statue of Liberty. The poem calls New York Harbor "the air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame". As a twin city to New York, it played a role in national affairs that was later overshadowed by its century-old submergence into its old partner and rival.

Economic growth continued, propelled by immigration and industrialization, and Brooklyn established itself as the third-most populous American city for much of the 19th century. The waterfront from Gowanus Bay to Greenpoint was developed with piers and factories. Industrial access to the waterfront was improved by the Gowanus Canal and the canalized Newtown Creek. USS Monitor was the most famous product of the large and growing shipbuilding industry of Williamsburg. After the Civil War, trolley lines and other transport brought urban sprawl beyond Prospect Park and into the center of the county.

The rapidly growing population needed more water, so the City built centralized waterworks including the Ridgewood Reservoir. The municipal Police Department, however, was abolished in 1854 in favor of a Metropolitan force covering also New York and Westchester Counties. In 1865 the Brooklyn Fire Department (BFD) also gave way to the new Metropolitan Fire District.

Throughout this period the peripheral towns of Kings County, far from Manhattan and even from urban Brooklyn, maintained their rustic independence. The only municipal change seen was the secession of the eastern section of the Town of Flatbush as the Town of New Lots in 1852. The building of rail links such as the Brighton Beach Line in 1878 heralded the end of this isolation.

_(14597683228).jpg)

Sports became big business, and the Brooklyn Bridegrooms played professional baseball at Washington Park in the convenient suburb of Park Slope and elsewhere. Early in the next century, under their new name of Brooklyn Dodgers, they brought baseball to Ebbets Field, beyond Prospect Park. Racetracks, amusement parks, and beach resorts opened in Brighton Beach, Coney Island, and elsewhere in the southern part of the county.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the City of Brooklyn experienced its final, explosive growth spurt. Railroads and industrialization spread to Bay Ridge and Sunset Park. Within a decade, the city had annexed the Town of New Lots in 1886, the Town of Flatbush, the Town of Gravesend, the Town of New Utrecht in 1894, and the Town of Flatlands in 1896. Brooklyn had reached its natural municipal boundaries at the ends of Kings County.

Mayors of the City of Brooklyn

Brooklyn elected a mayor from 1834 until consolidation in 1898 into the City of Greater New York, whose own second mayor (1902–1903), Seth Low, had been Mayor of Brooklyn from 1882 to 1885. Since 1898, Brooklyn has, in place of a separate mayor, elected a Borough President.

| Mayor | Start year | End year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| George Hall | Democratic-Republican | 1834 | 1834 | |

| Jonathan Trotter | Democratic | 1835 | 1836 | |

| Jeremiah Johnson | Whig | 1837 | 1838 | |

| Cyrus P. Smith | Whig | 1839 | 1841 | |

| Henry C. Murphy | Democratic | 1842 | 1842 | |

| Joseph Sprague | Democratic | 1843 | 1844 | |

| Thomas G. Talmage | Democratic | 1845 | 1845 | |

| Francis B. Stryker | Whig | 1846 | 1848 | |

| Edward Copland | Whig | 1849 | 1849 | |

| Samuel Smith | Democratic | 1850 | 1850 | |

| Conklin Brush | Whig | 1851 | 1852 | |

| Edward A. Lambert | Democratic | 1853 | 1854 | |

| George Hall | Know Nothing | 1855 | 1856 | |

| Samuel S. Powell | Democratic | 1857 | 1860 | |

| Martin Kalbfleisch | Democratic | 1861 | 1863 | |

| Alfred M. Wood | Republican | 1864 | 1865 | |

| Samuel Booth | Republican | 1866 | 1867 | |

| Martin Kalbfleisch | Democratic | 1868 | 1871 | |

| Samuel S. Powell | Democratic | 1872 | 1873 | |

| John W. Hunter | Democratic | 1874 | 1875 | |

| Frederick A. Schroeder | Republican | 1876 | 1877 | |

| James Howell | Democratic | 1878 | 1881 | |

| Seth Low | Republican | 1882 | 1885 | |

| Daniel D. Whitney | Democratic | 1886 | 1887 | |

| Alfred C. Chapin | Democratic | 1888 | 1891 | |

| David A. Boody | Democratic | 1892 | 1893 | |

| Charles A. Schieren | Republican | 1894 | 1895 | |

| Frederick W. Wurster | Republican | 1896 | 1897 |

New York City borough

In 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was completed, transportation to Manhattan was no longer by water only, and the City of Brooklyn's ties to the City of New York were strengthened.

The question became whether Brooklyn was prepared to engage in the still-grander process of consolidation then developing throughout the region, whether to join with the county of New York, the county of Richmond and the western portion of Queens County to form the five boroughs of a united City of New York. Andrew Haskell Green and other progressives said Yes, and eventually, they prevailed against the Daily Eagle and other conservative forces. In 1894, residents of Brooklyn and the other counties voted by a slight majority to merge, effective in 1898.[39]

Kings County retained its status as one of New York State's counties, but the loss of Brooklyn's separate identity as a city was met with consternation by some residents at the time. Many newspapers of the day called the merger the "Great Mistake of 1898", and the phrase still denotes Brooklyn pride among old-time Brooklynites.[40]

Geography

Brooklyn is 97 square miles (250 km2) in area, of which 71 square miles (180 km2) is land (73%), and 26 square miles (67 km2) is water (27%); the borough is the second-largest inland area among the New York City's boroughs. However, Kings County, coterminous with Brooklyn, is New York State's fourth-smallest county by land area and third-smallest by total area.[7] Brooklyn lies at the southwestern end of Long Island, and the borough's western border constitutes the island's western tip.

Brooklyn's water borders are extensive and varied, including Jamaica Bay; the Atlantic Ocean; The Narrows, separating Brooklyn from the borough of Staten Island in New York City and crossed by the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge; Upper New York Bay, separating Brooklyn from Jersey City and Bayonne in the U.S. state of New Jersey; and the East River, separating Brooklyn from the borough of Manhattan in New York City and traversed by the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Manhattan Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, and numerous routes of the New York City Subway. To the east of Brooklyn lies the borough of Queens, which contains John F. Kennedy International Airport in that borough's Jamaica neighborhood, approximately two miles from the border of Brooklyn's East New York neighborhood.

Boroughscape

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, using the 32 °F (0 °C) coldest month (January) isotherm, Brooklyn experiences a humid subtropical climate (Cfa),[41] with partial shielding from the Appalachian Mountains and moderating influences from the Atlantic Ocean. Brooklyn receives plentiful precipitation all year round, with nearly 50 in (1,300 mm) yearly. The area averages 234 days with at least some sunshine annually, and averages 57% of possible sunshine annually, accumulating 2,535 hours of sunshine per annum.[42] Brooklyn lies in the USDA 7b plant hardiness zone.[43]

| Climate data for JFK Airport, New York (1981–2010 normals,[44] extremes 1948–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

71 (22) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

98 (37) |

90 (32) |

77 (25) |

75 (24) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.8 (13.8) |

57.9 (14.4) |

68.5 (20.3) |

78.1 (25.6) |

84.9 (29.4) |

92.1 (33.4) |

94.5 (34.7) |

92.7 (33.7) |

87.4 (30.8) |

78.0 (25.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

96.6 (35.9) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 39.1 (3.9) |

41.8 (5.4) |

49.0 (9.4) |

59.0 (15.0) |

68.5 (20.3) |

78.0 (25.6) |

83.2 (28.4) |

81.9 (27.7) |

75.3 (24.1) |

64.5 (18.1) |

54.3 (12.4) |

44.0 (6.7) |

61.6 (16.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 26.3 (−3.2) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

34.2 (1.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

52.8 (11.6) |

62.8 (17.1) |

68.5 (20.3) |

67.8 (19.9) |

60.8 (16.0) |

49.6 (9.8) |

40.7 (4.8) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 9.8 (−12.3) |

13.4 (−10.3) |

19.1 (−7.2) |

32.6 (0.3) |

42.6 (5.9) |

52.7 (11.5) |

60.7 (15.9) |

58.6 (14.8) |

49.2 (9.6) |

37.6 (3.1) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

16.3 (−8.7) |

7.5 (−13.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

−2 (−19) |

4 (−16) |

20 (−7) |

34 (1) |

45 (7) |

55 (13) |

46 (8) |

40 (4) |

30 (−1) |

19 (−7) |

2 (−17) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.16 (80) |

2.59 (66) |

3.78 (96) |

3.87 (98) |

3.94 (100) |

3.86 (98) |

4.08 (104) |

3.68 (93) |

3.50 (89) |

3.62 (92) |

3.30 (84) |

3.39 (86) |

42.77 (1,086) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.3 (16) |

8.3 (21) |

3.5 (8.9) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

4.7 (12) |

23.8 (60) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 10.5 | 9.6 | 11.0 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 10.7 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 10.6 | 119.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 inch) | 4.6 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 13.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64.9 | 64.4 | 63.4 | 64.1 | 69.5 | 71.5 | 71.4 | 71.7 | 71.9 | 69.1 | 67.9 | 66.3 | 68.0 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity 1961–1990)[45][46][47] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

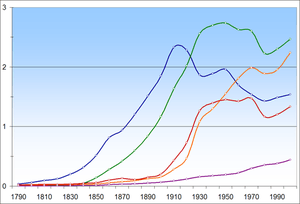

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1731 | 2,150 | — |

| 1756 | 2,707 | +25.9% |

| 1771 | 3,623 | +33.8% |

| 1786 | 3,966 | +9.5% |

| 1790 | 4,549 | +14.7% |

| 1800 | 5,740 | +26.2% |

| 1810 | 8,303 | +44.7% |

| 1820 | 11,187 | +34.7% |

| 1830 | 20,535 | +83.6% |

| 1840 | 47,613 | +131.9% |

| 1850 | 138,822 | +191.6% |

| 1860 | 279,122 | +101.1% |

| 1870 | 419,921 | +50.4% |

| 1880 | 599,495 | +42.8% |

| 1890 | 838,547 | +39.9% |

| 1900 | 1,166,582 | +39.1% |

| 1910 | 1,634,351 | +40.1% |

| 1920 | 2,018,356 | +23.5% |

| 1930 | 2,560,401 | +26.9% |

| 1940 | 2,698,285 | +5.4% |

| 1950 | 2,738,175 | +1.5% |

| 1960 | 2,627,319 | −4.0% |

| 1970 | 2,602,012 | −1.0% |

| 1980 | 2,230,936 | −14.3% |

| 1990 | 2,300,664 | +3.1% |

| 2000 | 2,465,326 | +7.2% |

| 2010 | 2,504,700 | +1.6% |

| 2019 | 2,559,903 | +2.2% |

| 1731–1786[48] U.S. Decennial Census[49] 1790–1960[50] 1900–1990[51] 1990–2000[52] 2010 and 2018[53] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[54] | ||

The United States Census Bureau has estimated Brooklyn's population has increased 2.2% to 2,559,903 between 2010 and 2019. Brooklyn's estimated population represented 30.7% of New York City's estimated population of 8,336,817; 33.5% of Long Island's population of 7,701,172; and 13.2% of New York State's population of 19,542,209.[55]

2010 Census

According to the 2010 United States Census, Brooklyn's population was 42.8% White, including 35.7% non-Hispanic White; 34.3% Black, including 31.9% non-Hispanic black; 10.5% Asian; 0.5% Native American; 0.0% (rounded) Pacific Islander; 3.0% Multiracial American; and 8.8% from Other races. Hispanics and Latinos made up 19.8% of Brooklyn's population.[57]

In 2010, Brooklyn had some neighborhoods segregated based on race, ethnicity, and religion. Overall, the southwest half of Brooklyn is racially mixed although it contains few black residents; the northeast section is mostly black and Hispanic/Latino.[59]

2018 estimates

According to the 2018 U.S. Census Bureau estimates, there are 2,582,830 people (up from 2.3 million in 1990), and 994,650 households, with 2.75 persons per household. The population density was 35,369/square mile. There are 1,053,767 housing units, with an owner-occupancy rate of 30.0%, and a median value of $623,900.[55]

In Brooklyn, the population was spread out to 7.2% under 5, 15.6% between 6–18, 63.3% 19–64, and 13.9% 65 and older. 52.6% of the population is female. 36.9% of the population are foreign born. Brooklyn's lesbian community is the largest out of all of the New York City boroughs.[55][60]

The median per capita income was $29,928, and the median household income was $52,782. 19.8% of the population lives below the poverty line. 606,738 people were employed.[55]

| Racial composition | 2018[61] | 2010[62] | 1990[63] | 1950[63] | 1900[63] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 49.5% | 42.8% | 46.9% | 92.2% | 98.3% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 36.4% | 35.7% | 40.1% | n/a | n/a |

| Black or African American | 34.1% | 34.3% | 37.9% | 7.6% | 1.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 19.1% | 19.8% | 20.1% | n/a | n/a |

| Asian | 12.7% | 10.5% | 4.8% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

Languages

Brooklyn has a high degree of linguistic diversity. As of 2010, 54.1% (1,240,416) of Brooklyn residents ages 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 17.2% (393,340) spoke Spanish, 6.5% (148,012) Chinese, 5.3% (121,607) Russian, 3.5% (79,469) Yiddish, 2.8% (63,019) French Creole, 1.4% (31,004) Italian, 1.2% (27,440) Hebrew, 1.0% (23,207) Polish, 1.0% (22,763) French, 1.0% (21,773) Arabic, 0.9% (19,388) various Indic languages, 0.7% (15,936) Urdu, and African languages were spoken as a main language by 0.5% (12,305) of the population over the age of five. In total, 45.9% (1,051,456) of Brooklyn's population ages 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[64]

Neighborhoods

Brooklyn's neighborhoods are dynamic in ethnic composition. For example, during the early to mid-20th century, Brownsville had a majority of Jewish residents; since the 1970s it has been majority African American. Midwood during the early 20th century was filled with ethnic Irish, then filled with Jewish residents for nearly 50 years, and is slowly becoming a Pakistani enclave. Brooklyn's most populous racial group, white, declined from 97.2% in 1930 to 46.9% by 1990.[63]

The borough attracts people previously living in other cities in the United States. Of these, most come from Chicago, Detroit, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston, Cincinnati, and Seattle.[65][66][67][68][69][70][71]

Community diversity

Given New York City's role as a crossroads for immigration from around the world, Brooklyn has evolved a globally cosmopolitan ambiance of its own, demonstrating a robust and growing demographic and cultural diversity with respect to metrics including nationality, religion, race, and domiciliary partnership. In 2010, 51.6% of the population was counted as members of religious congregations.[72] In 2014, there were 914 religious organizations in Brooklyn, the 10th most of all counties in the nation.[73] Brooklyn contains dozens of distinct neighborhoods representing many of the major culturally identified groups found within New York City. Among the most prominent are listed below:

Jewish American

Over 600,000 Jews, particularly Orthodox and Hasidic Jews, have become concentrated in Borough Park, Williamsburg, and Midwood, where there are many yeshivas, synagogues, and kosher restaurants, as well as many other Jewish businesses. Other notable religious Jewish neighborhoods are Kensington, Canarsie, Sea Gate, and Crown Heights (home to the Chabad world headquarters). Many hospitals in Brooklyn were started by Jewish charities, including Maimonides Medical Center in Borough Park and Brookdale Hospital in Brownsville.[74][75] Many non-Orthodox Jews (ranging from observant members of various denominations to atheists of Jewish cultural heritage) are concentrated in Ditmas Park and Park Slope, with smaller observant and culturally Jewish populations in Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, Brighton Beach, and Coney Island.

Chinese American

Over 200,000 Chinese Americans live throughout the southern parts of Brooklyn, in Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, Gravesend, and Homecrest. The largest concentration is in Sunset Park along 8th Avenue, known for its Chinese culture. It is called "Brooklyn's Chinatown" and its Chinese population is composed in majority by Fuzhounese Americans, rendering this Chinatown with the nicknames "Fuzhou Town (福州埠), Brooklyn" or the "Little Fuzhou (小福州)" of Brooklyn. Many Chinese restaurants can be found throughout Sunset Park, and the area hosts a popular Chinese New Year celebration.

Caribbean and African American

Brooklyn's African American and Caribbean communities are spread throughout much of Brooklyn. Brooklyn's West Indian community is concentrated in the Crown Heights, Flatbush, East Flatbush, Kensington, and Canarsie neighborhoods in central Brooklyn. Brooklyn is home to the largest community of West Indians outside of the Caribbean. Although the largest West Indian groups in Brooklyn are Jamaicans, Guyanese, and Haitians, there are West Indian immigrants from nearly every part of the Caribbean. Crown Heights and Flatbush are home to many of Brooklyn's West Indian restaurants and bakeries. Brooklyn has an annual, celebrated Carnival in the tradition of pre-Lenten celebrations in the islands.[76] Started by natives of Trinidad and Tobago, the West Indian Labor Day Parade takes place every Labor Day on Eastern Parkway. The Brooklyn Academy of Music also holds the DanceAfrica festival in late May, featuring street vendors and dance performances showcasing food and culture from all parts of Africa.[77][78] Bedford-Stuyvesant is home to one of the most famous African American communities in the city, along with Brownsville, East New York, and Coney Island.

Latino American

Bushwick is the largest hub of Brooklyn's Latino American community. Like other Latino neighborhoods in New York City, Bushwick has an established Puerto Rican presence, along with an influx of many Dominicans, South Americans, Central Americans, Mexicans, as well as a more recent influx of Puerto Ricans. As nearly 80% of Bushwick's population is Latino, its residents have created many businesses to support their various national and distinct traditions in food and other items. Sunset Park's population is 42% Latino, made up of these various ethnic groups. Brooklyn's main Latino groups are Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Dominicans, and Panamanians; they are spread out throughout the borough. Puerto Ricans and Dominicans are predominant in Bushwick, Williamsburg's South Side and East New York. Mexicans now predominate alongside Chinese immigrants in Sunset Park, although remnants of the neighborhood's once-substantial postwar Puerto Rican and Dominican communities continue to reside below 39th Street. A Panamanian enclave exists in Crown Heights.

Russian and Ukrainian American

Brooklyn is also home to many Russians and Ukrainians, who are mainly concentrated in the areas of Brighton Beach and Sheepshead Bay. Brighton Beach features many Russian and Ukrainian businesses and has been nicknamed Little Russia and Little Odessa, respectively. Originally these communities were mostly Jewish; however, in more recent years, the non-Jewish Russian and Ukrainian communities of Brighton Beach have grown, and the area now reflects diverse aspects of Russian and Ukrainian culture. Smaller concentrations of Russian and Ukrainian Americans are scattered elsewhere in southern Brooklyn, including Bay Ridge, Bensonhurst, Coney Island and Mill Basin.

Polish American

Brooklyn's Polish are historically concentrated in Greenpoint, home to Little Poland. Other longstanding settlements in Borough Park and Sunset Park have endured, while more recent immigrants are scattered throughout the southern parts of Brooklyn alongside the Russian American community.

Italian American

Despite widespread migration to Staten Island and more suburban areas in metropolitan New York throughout the postwar era, smaller concentrations of Italian Americans continue to reside in the neighborhoods of Bensonhurst, Dyker Heights, Bay Ridge, Bath Beach and Gravesend. Less perceptible remnants of older communities have persisted in Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens, where the homes of the remaining Italian Americans can often be contrasted with more recent upper middle class residents through the display of small Madonna statues, the retention of plastic-metal stoop awnings and the use of Formstone in house cladding. All of the aforementioned neighborhoods have retained Italian restaurants, bakeries, delicatessens, pizzerias, cafes and social clubs.

Muslim American

Today, Arab Americans and Pakistani Americans along with other Muslim communities have moved into the southwest portion of Brooklyn, particularly to Bay Ridge, where there are many Middle Eastern restaurants, hookah lounges, halal shops, Islamic shops, and mosques. Elsewhere, Coney Island Avenue is home to Little Pakistan, while Church Avenue is the center of a Bangladeshi community. Pakistani Independence Day is celebrated every year with parades and parties on Coney Island Avenue. Earlier, the area was known predominantly for its Irish, Norwegian, and Scottish populations. Beginning in the early 20th century, Syrian and Lebanese businesses, mosques, and restaurants were concentrated on Atlantic Avenue west of Flatbush Avenue in Boerum Hill; more recently, this area has evolved into a Yemeni commercial district.

Irish American

Third-, fourth- and fifth-generation Irish Americans can be found throughout Brooklyn, with moderate concentrations enduring in the neighborhoods of Windsor Terrace, Park Slope, Bay Ridge, Marine Park and Gerritsen Beach. Historical communities also existed in Vinegar Hill and other waterfront industrial neighborhoods, such as Greenpoint and Sunset Park. Paralleling the Italian American community, many moved to Staten Island and suburban areas in the postwar era. Those that stayed engendered close-knit, stable working-to-middle class communities through employment in the civil service (especially in law enforcement, transportation, and the New York City Fire Department) and the building and construction trades, while others were subsumed by the professional-managerial class and largely shed the Irish American community's distinct cultural traditions (including continued worship in the Catholic Church and other social activities, such as Irish stepdance and frequenting Irish American bars).

Greek American

Brooklyn's Greek Americans live throughout the borough, especially in Bay Ridge and adjacent areas where there is a noticeable cluster of Hellenic-focused schools and cultural institutions, with many businesses concentrated there and in Downtown Brooklyn near Atlantic Avenue. Greek-owned diners are also found throughout the borough.

LGBTQ community

Brooklyn is home to a large and growing number of same-sex couples. Same-sex marriages in New York were legalized on June 24, 2011 and were authorized to take place beginning 30 days thereafter.[79] The Park Slope neighborhood spearheaded the popularity of Brooklyn among lesbians, and Prospect Heights has an LGBT residential presence.[80] Numerous neighborhoods have since become home to LGBT communities. Brooklyn Liberation March, the largest transgender-rights demonstration in LGBTQ history, took place on June 14, 2020 stretching from Grand Army Plaza to Fort Greene, focused on supporting Black transgender lives, drawing an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 participants.[81][82]

Artists-in-residence

Brooklyn became a preferred site for artists and hipsters to set up live/work spaces after being priced out of the same types of living arrangements in Manhattan. Various neighborhoods in Brooklyn, including Williamsburg, DUMBO, Red Hook, and Park Slope evolved as popular neighborhoods for artists-in-residence. However, rents and costs of living have since increased dramatically in these same neighborhoods, forcing artists to move to somewhat less expensive neighborhoods in Brooklyn or across Upper New York Bay to locales in New Jersey, such as Jersey City or Hoboken.[83]

Government and politics

Since consolidation with New York City in 1898, Brooklyn has been governed by the New York City Charter that provides for a "strong" mayor–council system. The centralized government of New York City is responsible for public education, correctional institutions, public safety, recreational facilities, sanitation, water supply, and welfare services. On the other hand, the Brooklyn Public Library is an independent nonprofit organization partially funded by the government of New York City, but also by the government of New York State, the U.S. federal government, and private donors.

The office of Borough President was created in the consolidation of 1898 to balance centralization with the local authority. Each borough president had a powerful administrative role derived from having a vote on the New York City Board of Estimate, which was responsible for creating and approving the city's budget and proposals for land use. In 1989, the Supreme Court of the United States declared the Board of Estimate unconstitutional because Brooklyn, the most populous borough, had no greater effective representation on the Board than Staten Island, the least populous borough; it was a violation of the high court's 1964 "one man, one vote" reading of the Fourteenth Amendment.[84]

Since 1990, the Borough President has acted as an advocate for the borough at the mayoral agencies, the City Council, the New York state government, and corporations. Brooklyn's current Borough President is Eric Adams, elected as a Democrat in November 2013 with 90.8% of the vote. Adams replaced popular Borough President Marty Markowitz, also a Democrat, who partially used his office to promote tourism and new development for Brooklyn.

Democrats hold most public offices, and the borough is very liberal. As of November 2017, 89.1% of registered voters in Brooklyn were Democrats.[85] Party platforms center on affordable housing, education and economic development. Pockets of Republican influence exist in Gravesend, Bensonhurst, Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights and Midwood.

Each of the city's five counties (coterminous with each borough) has its own criminal court system and District Attorney, the chief public prosecutor who is directly elected by popular vote. The District Attorney of Kings County is Eric Gonzalez, who replaced Democrat Kenneth P. Thompson following his death in October 2016.[86] Brooklyn has 16 City Council members, the largest number of any of the five boroughs. Brooklyn has 18 of the city's 59 community districts, each served by an unpaid Community Board with advisory powers under the city's Uniform Land Use Review Procedure. Each board has a paid district manager who acts as an interlocutor with city agencies.

Federal representation

As is the case with sister boroughs Manhattan and the Bronx, Brooklyn has not voted for a Republican in a national presidential election since Calvin Coolidge in 1924. In the 2008 presidential election, Democrat Barack Obama received 79.4% of the vote in Brooklyn while Republican John McCain received 20.0%. In 2012, Barack Obama increased his Democratic margin of victory in the borough, dominating Brooklyn with 82.0% of the vote to Republican Mitt Romney's 16.9%.

In 2019, five Democrats represented Brooklyn in the United States House of Representatives. One congressional district lies entirely within the borough.[87]

- Nydia Velázquez (first elected in 1992) represents New York's 7th congressional district, which includes the central-west Brooklyn neighborhoods of Brooklyn Heights, Boerum Hill, Bushwick, Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, Dumbo, East New York, East Williamsburg, Greenpoint, Gowanus, Red Hook, Sunset Park, and Williamsburg. The district also covers a small portion of Queens.[87]

- Hakeem Jeffries (first elected in 2012) represents New York's 8th congressional district, which includes the southern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Bergen Beach, Brighton Beach, Brownsville, Brighton Beach, Canarsie, Clinton Hill, Coney Island, East Flatbush, East New York, Fort Greene, Gerritsen Beach, Marine Park, Mill Basin, Ocean Hill, Sheepshead Bay, and Spring Creek. The district also covers a small portion of Queens.[87]

- Yvette Clarke (first elected in 2006) represents New York's 9th congressional district, which includes the central and southern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Crown Heights, East Flatbush, Flatbush, Midwood, Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, and Windsor Terrace.[87]

- Jerrold Nadler (first elected in 1992) represents New York's 10th congressional district, which includes the southwestern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Midwood, Red Hook, Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, Borough Park, Gravesend, Kensington, and Mapleton. The district also covers the West Side of Manhattan.[87]

- Max Rose (first elected in 2018) represents New York's 11th congressional district, which includes the southwestern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bensonhurst, Gravesend, Bath Beach, Bay Ridge, and Dyker Heights. The district also covers all of Staten Island.[87]

Economy

%2C_June_1940.jpg)

Brooklyn's job market is driven by three main factors: the performance of the national and city economy, population flows and the borough's position as a convenient back office for New York's businesses.[88]

Forty-four percent of Brooklyn's employed population, or 410,000 people, work in the borough; more than half of the borough's residents work outside its boundaries. As a result, economic conditions in Manhattan are important to the borough's jobseekers. Strong international immigration to Brooklyn generates jobs in services, retailing and construction.[88]

Since the late 20th century, Brooklyn has benefited from a steady influx of financial back office operations from Manhattan, the rapid growth of a high-tech and entertainment economy in DUMBO, and strong growth in support services such as accounting, personal supply agencies, and computer services firms.[88]

Jobs in the borough have traditionally been concentrated in manufacturing, but since 1975, Brooklyn has shifted from a manufacturing-based to a service-based economy. In 2004, 215,000 Brooklyn residents worked in the services sector, while 27,500 worked in manufacturing. Although manufacturing has declined, a substantial base has remained in apparel and niche manufacturing concerns such as furniture, fabricated metals, and food products.[89] The pharmaceutical company Pfizer was founded in Brooklyn in 1869 and had a manufacturing plant in the borough for many years that employed thousands of workers, but the plant shut down in 2008. However, new light-manufacturing concerns packaging organic and high-end food have sprung up in the old plant.[90]

First established as a shipbuilding facility in 1801, the Brooklyn Navy Yard employed 70,000 people at its peak during World War II and was then the largest employer in the borough. The Missouri, the ship on which the Japanese formally surrendered, was built there, as was the Maine, whose sinking off Havana led to the start of the Spanish–American War. The iron-sided Civil War vessel the Monitor was built in Greenpoint. From 1968–1979 Seatrain Shipbuilding was the major employer.[91] Later tenants include industrial design firms, food processing businesses, artisans, and the film and television production industry. About 230 private-sector firms providing 4,000 jobs are at the Yard.

Construction and services are the fastest growing sectors.[92] Most employers in Brooklyn are small businesses. In 2000, 91% of the approximately 38,704 business establishments in Brooklyn had fewer than 20 employees.[93] As of August 2008, the borough's unemployment rate was 5.9%.[94]

Brooklyn is also home to many banks and credit unions. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, there were 37 banks and 26 credit unions operating in the borough in 2010.[95][96]

The rezoning of Downtown Brooklyn has generated over US$10 billion of private investment and $300 million in public improvements since 2004. Brooklyn is also attracting numerous high technology start-up companies, as Silicon Alley, the metonym for New York City's entrepreneurship ecosystem, has expanded from Lower Manhattan into Brooklyn.[97]

Culture

Brooklyn has played a major role in various aspects of American culture including literature, cinema, and theater. The Brooklyn accent has often been portrayed as the "typical New York accent" in American media, although this accent and stereotype are supposedly fading out.[98] Brooklyn's official colors are blue and gold.[99]

Cultural venues

Brooklyn hosts the world-renowned Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Philharmonic, and the second-largest public art collection in the United States, housed in the Brooklyn Museum.

The Brooklyn Museum, opened in 1897, is New York City's second-largest public art museum. It has in its permanent collection more than 1.5 a million objects, from ancient Egyptian masterpieces to contemporary art. The Brooklyn Children's Museum, the world's first museum dedicated to children, opened in December 1899. The only such New York State institution accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, it is one of the few globally to have a permanent collection – over 30,000 cultural objects and natural history specimens.

The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) includes a 2,109-seat opera house, an 874-seat theater, and the art-house BAM Rose Cinemas. Bargemusic and St. Ann's Warehouse are on the other side of Downtown Brooklyn in the DUMBO arts district. Brooklyn Technical High School has the second-largest auditorium in New York City (after Radio City Music Hall), with a seating capacity of over 3,000.[100]

Media

Local periodicals

Brooklyn has several local newspapers: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Bay Currents (Oceanfront Brooklyn), Brooklyn View, The Brooklyn Paper, and Courier-Life Publications. Courier-Life Publications, owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, is Brooklyn's largest chain of newspapers. Brooklyn is also served by the major New York dailies, including The New York Times, the New York Daily News, and the New York Post.

The borough is home to the arts and politics monthly Brooklyn Rail, as well as the arts and cultural quarterly Cabinet. Hello Mr. is also published in Brooklyn.

Brooklyn Magazine is one of the few glossy magazines about Brooklyn. Several others are now defunct, including BKLYN Magazine (a bimonthly lifestyle book owned by Joseph McCarthy, that saw itself as a vehicle for high-end advertisers in Manhattan and was mailed to 80,000 high-income households), Brooklyn Bridge Magazine, The Brooklynite (a free, glossy quarterly edited by Daniel Treiman), and NRG (edited by Gail Johnson and originally marketed as a local periodical for Clinton Hill and Fort Greene, but expanded in scope to become the self-proclaimed "Pulse of Brooklyn" and then the "Pulse of New York").[101]

Ethnic press

Brooklyn has a thriving ethnic press. El Diario La Prensa, the largest and oldest Spanish-language daily newspaper in the United States, maintains its corporate headquarters at 1 MetroTech Center in downtown Brooklyn.[102] Major ethnic publications include the Brooklyn-Queens Catholic paper The Tablet, Hamodia, an Orthodox Jewish daily and The Jewish Press, an Orthodox Jewish weekly. Many nationally distributed ethnic newspapers are based in Brooklyn. Over 60 ethnic groups, writing in 42 languages, publish some 300 non-English language magazines and newspapers in New York City. Among them is the quarterly "L'Idea", a bilingual magazine printed in Italian and English since 1974. In addition, many newspapers published abroad, such as The Daily Gleaner and The Star of Jamaica, are available in Brooklyn. Our Time Press published weekly by DBG Media covers the Village of Brooklyn with a motto of "The Local paper with the Global-View".

Television

The City of New York has an official television station, run by NYC Media, which features programming based in Brooklyn. Brooklyn Community Access Television is the borough's public access channel.[103] It’s studios are at the BRIC Arts Media venue, called BRIC House, located on Fulton Street in the Fort Greene section of the borough.[104]

Events

- The annual Coney Island Mermaid Parade (mid-to-late June) is a costume-and-float parade.[105]

- Coney Island also hosts the annual Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest (July 4).[105]

- The annual Labor Day Carnival (also known as the Labor Day Parade or West Indian Day Parade) takes place along Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights.

- The Art of Brooklyn Film Festival runs annually around the second week of June.[106]

Parks and other attractions

- Brooklyn Botanic Garden: adjacent to Prospect Park is the 52-acre (21 ha) botanical garden, which includes a cherry tree esplanade, a one-acre (0.4 ha) rose garden, a Japanese hill, and pond garden, a fragrance garden, a water lily pond esplanade, several conservatories, a rock garden, a native flora garden, a bonsai tree collection, and children's gardens and discovery exhibits.

- Coney Island developed as a playground for the rich in the early 1900s, but it grew as one of America's first amusement grounds and attracted crowds from all over New York. The Cyclone rollercoaster, built-in 1927, is on the National Register of Historic Places. The 1920 Wonder Wheel and other rides are still operational. Coney Island went into decline in the 1970s but has undergone a renaissance.[107]

- Floyd Bennett Field: the first municipal airport in New York City and long-closed for operations, is now part of the National Park System. Many of the historic hangars and runways are still extant. Nature trails and diverse habitats are found within the park, including salt marsh and a restored area of shortgrass prairie that was once widespread on the Hempstead Plains.

- Green-Wood Cemetery, founded by the social reformer Henry Evelyn Pierrepont in 1838, is an early Rural cemetery. It is the burial ground of many notable New Yorkers.

- Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge: a unique Federal wildlife refuge straddling the Brooklyn-Queens border, part of Gateway National Recreation Area

- New York Transit Museum displays historical artifacts of Greater New York's subway, commuter rail, and bus systems; it is at Court Street, a former Independent Subway System station in Brooklyn Heights on the Fulton Street Line.

- Prospect Park is a public park in central Brooklyn encompassing 585 acres (2.37 km2).[108] The park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who created Manhattan's Central Park. Attractions include the Long Meadow, a 90-acre (36 ha) meadow, the Picnic House, which houses offices and a hall that can accommodate parties with up to 175 guests; Litchfield Villa, Prospect Park Zoo, the Boathouse, housing a visitors center and the first urban Audubon Center;[109] Brooklyn's only lake, covering 60 acres (24 ha); the Prospect Park Bandshell that hosts free outdoor concerts in the summertime; and various sports and fitness activities including seven baseball fields. Prospect Park hosts a popular annual Halloween Parade.

- Fort Greene Park is a public park in the Fort Greene Neighborhood. The park contains the Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument, a monument to American prisoners during the revolutionary war.

Sports

Brooklyn's major professional sports team is the NBA's Brooklyn Nets. The Nets moved into the borough in 2012, and play their home games at Barclays Center in Prospect Heights. Previously, the Nets had played in Uniondale, New York and in New Jersey. In April 2020, the New York Liberty of the WNBA were sold to the Nets' owners and moved their home venue from Madison Square Garden to the Barclays Center.

Barclays Center was also the home arena for the NHL's New York Islanders full-time from 2015 to 2018, then part-time from 2018 to 2020 (alternating with Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale). The Islanders had originally played at Nassau Coliseum full-time since their inception until 2015, when their lease at the venue expired and the team moved to Barclays Center. In 2020, the team will return to Nassau Coliseum full-time for one season before moving to their new permanent home at Belmont Park in 2021.

Brooklyn also has a storied sports history. It has been home to many famous sports figures such as Joe Paterno, Vince Lombardi, Mike Tyson, Joe Torre, Sandy Koufax, Billy Cunningham and Vitas Gerulaitis. Basketball legend Michael Jordan was born in Brooklyn though he grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina.

In the earliest days of organized baseball, Brooklyn teams dominated the new game. The second recorded game of baseball was played near what is today Fort Greene Park on October 24, 1845. Brooklyn's Excelsiors, Atlantics and Eckfords were the leading teams from the mid-1850s through the Civil War, and there were dozens of local teams with neighborhood league play, such as at Mapleton Oval.[110] During this "Brooklyn era", baseball evolved into the modern game: the first fastball, first changeup, first batting average, first triple play, first pro baseball player, first enclosed ballpark, first scorecard, first known African-American team, first black championship game, first road trip, first gambling scandal, and first eight pennant winners were all in or from Brooklyn.[111]

Brooklyn's most famous historical team, the Brooklyn Dodgers, named for "trolley dodgers" played at Ebbets Field.[112] In 1947 Jackie Robinson was hired by the Dodgers as the first African-American player in Major League Baseball in the modern era. In 1955, the Dodgers, perennial National League pennant winners, won the only World Series for Brooklyn against their rival New York Yankees. The event was marked by mass euphoria and celebrations. Just two years later, the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles. Walter O'Malley, the team's owner at the time, is still vilified, even by Brooklynites too young to remember the Dodgers as Brooklyn's ball club.

After a 43-year hiatus, professional baseball returned to the borough in 2001 with the Brooklyn Cyclones, a minor league team that plays in MCU Park in Coney Island. They are an affiliate of the New York Mets. The New York Cosmos of the NASL began playing at MCU Park in 2017.[113]

Brooklyn once had a National Football League team named the Brooklyn Lions in 1926, who played at Ebbets Field.[114]

Rugby United New York joined Major League Rugby in 2019, and play their home games at MCU Park.

Brooklyn has one of the most active recreational fishing fleets in the United States. In addition to a large private fleet along Jamaica Bay, there is a substantial public fleet within Sheepshead Bay. Species caught include Black Fish, Porgy, Striped Bass, Black Sea Bass, Fluke, and Flounder.[115][116][117]

Transportation

Public transport

About 57 percent of all households in Brooklyn were households without automobiles. The citywide rate is 55 percent in New York City.[118]

Brooklyn features extensive public transit. Nineteen New York City Subway services, including the Franklin Avenue Shuttle, traverse the borough. Approximately 92.8% of Brooklyn residents traveling to Manhattan use the subway, despite the fact some neighborhoods like Flatlands and Marine Park are poorly served by subway service. Major stations, out of the 170 currently in Brooklyn, include:

- Atlantic Avenue – Barclays Center

- Broadway Junction

- DeKalb Avenue

- Jay Street – MetroTech

- Coney Island – Stillwell Avenue[119]

Proposed New York City Subway lines never built include a line along Nostrand or Utica Avenues to Marine Park,[120] as well as a subway line to Spring Creek.[121][122]

Brooklyn was once served by an extensive network of streetcars, but many were replaced by the public bus network that covers the entire borough. There is also daily express bus service into Manhattan.[123] New York's famous yellow cabs also provide transportation in Brooklyn, although they are less numerous in the borough. There are three commuter rail stations in Brooklyn: East New York, Nostrand Avenue, and Atlantic Terminal, the terminus of the Atlantic Branch of the Long Island Rail Road. The terminal is near the Atlantic Avenue – Barclays Center subway station, with ten connecting subway services.

In February 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city government would begin a citywide ferry service called NYC Ferry to extend ferry transportation to communities in the city that have been traditionally underserved by public transit.[124][125] The ferry opened in May 2017,[126][127] with the Bay Ridge ferry serving southwestern Brooklyn and the East River Ferry serving northwestern Brooklyn. A third route, the Rockaway ferry, makes one stop in the borough at Brooklyn Army Terminal.[128]

A streetcar line, the Brooklyn–Queens Connector, was proposed by the city in February 2016,[129] with the planned timeline calling for service to begin around 2024.[130]

Roadways

[[File:View of Eastern Parkway Looking towards Museum Eugene Wemlinger ca. 1903- 1910 Brooklyn Museum.jpg|upright=1.8|thumb|right|View of Eastern Parkway looking toward the Brooklyn Museum, cellulose nitrate negative photograph by Eugene Wemlinger {{circa|1903–1910|| Brooklyn Museum ]]

Most of the limited-access expressways and parkways are in the western and southern sections of Brooklyn, where the borough's two interstate highways are located; Interstate 278, which uses the Gowanus Expressway and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, traverses Sunset Park and Brooklyn Heights, while Interstate 478 is an unsigned route designation for the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel, which connects to Manhattan.[131] Other prominent roadways are the Prospect Expressway (New York State Route 27), the Belt Parkway, and the Jackie Robinson Parkway (formerly the Interborough Parkway). Planned expressways that were never built include the Bushwick Expressway, an extension of I-78[132] and the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway, I-878.[133] Major thoroughfares include Atlantic Avenue, Fourth Avenue, 86th Street, Kings Highway, Bay Parkway, Ocean Parkway, Eastern Parkway, Linden Boulevard, McGuinness Boulevard, Flatbush Avenue, Pennsylvania Avenue, and Nostrand Avenue.

Much of Brooklyn has only named streets, but Park Slope, Bay Ridge, Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, and Borough Park and the other western sections have numbered streets running approximately northwest to southeast, and numbered avenues going approximately northeast to southwest. East of Dahill Road, lettered avenues (like Avenue M) run east and west, and numbered streets have the prefix "East". South of Avenue O, related numbered streets west of Dahill Road use the "West" designation. This set of numbered streets ranges from West 37th Street to East 108 Street, and the avenues range from A–Z with names substituted for some of them in some neighborhoods (notably Albemarle, Beverley, Cortelyou, Dorchester, Ditmas, Foster, Farragut, Glenwood, Quentin). Numbered streets prefixed by "North" and "South" in Williamsburg, and "Bay", "Beach", "Brighton", "Plumb", "Paerdegat" or "Flatlands" along the southern and southwestern waterfront are loosely based on the old grids of the original towns of Kings County that eventually consolidated to form Brooklyn. These names often reflect the bodies of water or beaches around them, such as Plumb Beach or Paerdegat Basin.

Brooklyn is connected to Manhattan by three bridges, the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg Bridges; a vehicular tunnel, the Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel (also known as the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel); and several subway tunnels. The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge links Brooklyn with the more suburban borough of Staten Island. Though much of its border is on land, Brooklyn shares several water crossings with Queens, including the Pulaski Bridge, the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge, the Kosciuszko Bridge (part of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway), and the Grand Street Bridge, all of which carry traffic over Newtown Creek, and the Marine Parkway Bridge connecting Brooklyn to the Rockaway Peninsula.

Waterways

Brooklyn was long a major shipping port, especially at the Brooklyn Army Terminal and Bush Terminal in Sunset Park. Most container ship cargo operations have shifted to the New Jersey side of New York Harbor, while the Brooklyn Cruise Terminal in Red Hook is a focal point for New York's growing cruise industry. The Queen Mary 2, one of the world's largest ocean liners, was designed specifically to fit under the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, the longest suspension bridge in the United States. She makes regular ports of call at the Red Hook terminal on her transatlantic crossings from Southampton, England.[128]

In February 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city government would begin NYC Ferry to extend ferry transportation to traditionally underserved communities in the city.[124][125] The ferry opened in May 2017,[126][127] offering commuter services from the western shore of Brooklyn to Manhattan via three routes. The East River Ferry serves points in Lower Manhattan, Midtown, Long Island City, and northwestern Brooklyn via its East River route. The South Brooklyn and Rockaway routes serve southwestern Brooklyn before terminating in lower Manhattan. Ferries to Coney Island are also planned.[128] NY Waterway offers tours and charters. SeaStreak also offers a weekday ferry service between the Brooklyn Army Terminal and the Manhattan ferry slips at Pier 11/Wall Street downtown and East 34th Street Ferry Landing in midtown. A Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel, originally proposed in the 1920s as a core project for the then-new Port Authority of New York is again being studied and discussed as a way to ease freight movements across a large swath of the metropolitan area.

Education

.jpg)

Education in Brooklyn is provided by a vast number of public and private institutions. Public schools in the borough are managed by the New York City Department of Education, the largest public school system.

Brooklyn Technical High School (commonly called Brooklyn Tech), a New York City public high school, is the largest specialized high school for science, mathematics, and technology in the United States.[134] Brooklyn Tech opened in 1922. Brooklyn Tech is across the street from Fort Greene Park. This high school was built from 1930 to 1933 at a cost of about $6 million and is 12 stories high. It covers about half of a city block.[135] Brooklyn Tech is noted for its famous alumni[136] (including two Nobel Laureates), its academics, and a large number of graduates attending prestigious universities.

Higher education

Public colleges

Brooklyn College is a senior college of the City University of New York, and was the first public coeducational liberal arts college in New York City. The College ranked in the top 10 nationally for the second consecutive year in Princeton Review’s 2006 guidebook, America’s Best Value Colleges. Many of its students are first and second-generation Americans. Founded in 1970, Medgar Evers College is a senior college of the City University of New York, with a mission to develop and maintain high quality, professional, career-oriented undergraduate degree programs in the context of a liberal arts education. The College offers programs at the baccalaureate and associate degree levels, as well as adult and continuing education classes for central Brooklyn residents, corporations, government agencies, and community organizations. Medgar Evers College is a few blocks east of Prospect Park in Crown Heights.

CUNY's New York City College of Technology (City Tech) of The City University of New York (CUNY) (Downtown Brooklyn/Brooklyn Heights) is the largest public college of technology in New York State and a national model for technological education. Established in 1946, City Tech can trace its roots to 1881 when the Technical Schools of the Metropolitan Museum of Art were renamed the New York Trade School. That institution—which became the Voorhees Technical Institute many decades later—was soon a model for the development of technical and vocational schools worldwide. In 1971, Voorhees was incorporated into City Tech.

SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, founded as the Long Island College Hospital in 1860, is the oldest hospital-based medical school in the United States. The Medical Center comprises the College of Medicine, College of Health Related Professions, College of Nursing, School of Public Health, School of Graduate Studies, and University Hospital of Brooklyn. The Nobel Prize winner Robert F. Furchgott was a member of its faculty. Half of the Medical Center's students are minorities or immigrants. The College of Medicine has the highest percentage of minority students of any medical school in New York State.

Private colleges

Brooklyn Law School was founded in 1901 and is notable for its diverse student body. Women and African Americans were enrolled in 1909. According to the Leiter Report, a compendium of law school rankings published by Brian Leiter, Brooklyn Law School places 31st nationally for the quality of students.[137]

Long Island University is a private university headquartered in Brookville on Long Island, with a campus in Downtown Brooklyn with 6,417 undergraduate students. The Brooklyn campus has a strong science and medical technology programs, at the graduate and undergraduate levels.

Pratt Institute, in Clinton Hill, is a private college founded in 1887 with programs in engineering, architecture, and the arts. Some buildings in the school's Brooklyn campus are official landmarks. Pratt has over 4700 students, with most at its Brooklyn campus. Graduate programs include a library and information science, architecture, and urban planning. Undergraduate programs include architecture, construction management, writing, critical and visual studies, industrial design and fine arts, totaling over 25 programs in all.

The New York University Tandon School of Engineering, the United States' second oldest private institute of technology, founded in 1854, has its main campus in Downtown's MetroTech Center, a commercial, civic and educational redevelopment project of which it was a key sponsor. NYU-Tandon is one of the 18 schools and colleges that comprise New York University (NYU).[138][139][140][141]

St. Francis College is a Catholic college in Brooklyn Heights founded in 1859 by Franciscan friars. Today, over 2,400 students attend the small liberal arts college. St. Francis is considered by The New York Times as one of the more diverse colleges, and was ranked one of the best baccalaureate colleges by Forbes magazine and U.S. News & World Report.[142][143][144]

Brooklyn also has smaller liberal arts institutions, such as Saint Joseph's College in Clinton Hill and Boricua College in Williamsburg.

Community colleges

Kingsborough Community College is a junior college in the City University of New York system in Manhattan Beach.

Brooklyn Public Library

As an independent system, separate from the New York and Queens public library systems, the Brooklyn Public Library[145] offers thousands of public programs, millions of books, and use of more than 850 free Internet-accessible computers. It also has books and periodicals in all the major languages spoken in Brooklyn, including English, Russian, Chinese, Spanish, Hebrew, and Haitian Creole, as well as French, Yiddish, Hindi, Bengali, Polish, Italian, and Arabic. The Central Library is a landmarked building facing Grand Army Plaza.

There are 58 library branches, placing one within a half-mile of each Brooklyn resident. In addition to its specialized Business Library in Brooklyn Heights, the Library is preparing to construct its new Visual & Performing Arts Library (VPA) in the BAM Cultural District, which will focus on the link between new and emerging arts and technology and house traditional and digital collections. It will provide access and training to arts applications and technologies not widely available to the public. The collections will include the subjects of art, theater, dance, music, film, photography, and architecture. A special archive will house the records and history of Brooklyn's arts communities.

Partnerships with districts of foreign cities

- Anzio, Lazio, Italy (since 1990)

- Huế, Vietnam

- Gdynia, Poland (since 1991)[146]

- Beşiktaş, Istanbul Province, Turkey (since 2005)[147]

- Leopoldstadt, Vienna, Austria (since 2007)[148][149][150]

- London Borough of Lambeth, United Kingdom[151]

- Bnei Brak, Israel[152]

- Konak, İzmir, Turkey (since 2010)[153]

- Chaoyang District, Beijing, China (since 2014)[154]

- Yiwu, China (since 2014)[154]

- Üsküdar, Istanbul, Turkey (since 2015)[155]

Hospitals and healthcare

- Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center [156]

- Kings County Hospital Center

- NYC Health + Hospitals/Kings County

Notable people

See also

General links

|

History of neighborhoods

|

General history

|

References

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Kings County (Brooklyn Borough), New York".

- Moynihan, Colin. "F.Y.I.", The New York Times, September 19, 1999. Accessed December 17, 2019. "There are well-known names for inhabitants of four boroughs: Manhattanites, Brooklynites, Bronxites and Staten Islanders. But what are residents of Queens called?"

- Local Area Gross Domestic Product, 2018, Bureau of Economic Analysis, released December 12, 2019. Accessed December 17, 2019.

- GCT-PH1; Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2000 – United States – County by State; and for Puerto Rico from the Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data , United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- The most densely populated county is New York County (which is coextensive with the borough of Manhattan).[4]

- https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/2020-population/t8c6-3i7b

- 2010 Gazetteer for New York State, United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Henry Alford (May 1, 2013). "How I Became a Hipster". The New York Times. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- Oshrat Carmiel (April 9, 2015). "Brooklyn Home Prices Jump 18% to Record as Buyers Compete". Bloomberg, L.P. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "19 Reasons Why Brooklyn Is New York's New Startup Hotspot". CB Insights. October 19, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- Vanessa Friedman (April 30, 2016). "Brooklyn's Wearable Revolution". The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- Alexandria Symonds (April 29, 2016). "One Celebrated Brooklyn Artist's Futuristic New Practice". The New York Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- "Current Population Estimates: NYC". NYC.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- "GDP by County | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)". www.bea.gov.

- QuickFacts New York city, New York; Bronx County (Bronx Borough), New York; Kings County (Brooklyn Borough), New York; New York County (Manhattan Borough), New York; Queens County (Queens Borough), New York; Richmond County (Staten Island Borough), New York, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 11, 2018.

- Manten, A. A. (June 19, 2020). "Hoe oud is Breukelen?". Tijdschrift Historische Kring Breukelen. 1983, volume 2: 72 – via Utrecht University.

- Faber, Hans (June 19, 2020). "Attingahem Bridge". www.frisiacoasttrail.com.

- Carroll, Maurice (September 16, 1971). "Historical District Named in Brooklyn". The New York Times. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- Dexter, Franklin B. (April 1885). "The History of Connecticut, as Illustrated by the Names of Her Towns". Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. American Antiquarian Society: 438.

- Powell, Lyman Pierson (1899). Historic Towns of the Middle States. G. P. Putnam's sons. p. 216. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- Winter, J. M. Van (1998). Sources concerning the hospitallers of St John in the Netherlands: 14th–18th centuries. Brill. p. 765. ISBN 9004108033. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- Ellis, Edward Robb (2011). The Epic of New York City: A Narrative History. Basic Books. p. 42. ISBN 9780465030538. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- Rensselaer, Schuyler Van (1909). History of the City of New York in the Seventeenth Century: New York under the Stuarts. Macmillan. p. 149. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1910). "Brooklyn". The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 648. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, "Map of six townships"

- Notes Geographical and Historical, relating to the Town of Brooklyn, in Kings County on Long-Island.

- N.Y. Col. Laws, ch4/1:122

- "Slavery Here. Right in Brooklyn and Out on Long Island". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 29, 1891. p. 2. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- McCullough, David. 1776. Simon & Schuster. 2005. ISBN 978-0-7432-2671-4

- "The Brooklyn Eagle and Kings County Democrat". October 26, 1841. Retrieved July 29, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Brooklyn Eagle and Kings County Democrat". October 26, 1841. Retrieved July 29, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Brooklyn Eagle and Kings County Democrat". bklyn.newspapers.com. Newspapers.com. October 26, 1841. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- "The Brooklyn Eagle and Kings County Democrat". October 26, 1841. Retrieved July 29, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Brooklyn Eagle and Kings County Democrat". October 26, 1841. Retrieved July 29, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Abolitionist Brooklyn (1828–1849) | In Pursuit of Freedom". Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol. III, (1847), London, Charles Knight, p. 852

- Jacob Judd, "Policing the City of Brooklyn in the 1840s and 1850s", Journal of Long Island History (1966) (6)2 pp. 13–22.

- The Encyclopedia of New York City; (p. 149, 3rd Column.)

- The 100 Year Anniversary of the Consolidation of the 5 Boroughs into New York City, City of New York, retrieved January 31, 2008

- McCullough, David W; Kalett, Jim (1983). Brooklyn – and how it got that way. New York: Dial Press. p. 58. ISBN 0385274270. OCLC 8667213.