Montgomery County, Maryland

Montgomery County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of Maryland, located adjacent to Washington, D.C. As of the 2010 census, the county's population was 971,777, increasing by 8.1% to an estimated 1,050,688 in 2019.[6] The county seat and largest municipality is Rockville, although the census-designated place of Germantown is the most populous city within the county.[7] Montgomery County is included in the Washington–Arlington–Alexandria, DC–VA–MD–WV Metropolitan Statistical Area, which in turn forms part of the Baltimore–Washington Combined Statistical Area. Most of the county's residents live in unincorporated locales, of which the most urban are Silver Spring and Bethesda, although the incorporated cities of Rockville and Gaithersburg are also large population centers, as are many smaller but significant places.[N 1]

Montgomery County, Maryland | |

|---|---|

| County of Montgomery[1] | |

Clockwise: Downtown Bethesda, Spring Street in Silver Spring, Billy Goat B Trail, rural Darnestown, Rockville town center, Great Falls on the Potomac River. | |

Seal  Coat of arms  Emblem | |

| Nickname(s): "MoCo" | |

| Motto(s): French: Gardez Bien (English: Watch Well) | |

Location in the U.S. state of Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°08′11″N 77°12′15″W[2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | September 6, 1776[3][4] |

| Named for | Richard Montgomery |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Marc Elrich (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 507 sq mi (1,310 km2) |

| • Land | 491 sq mi (1,270 km2) |

| • Water | 16 sq mi (40 km2) 3.1% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 971,777 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 1,050,688 |

| • Density | 1,900/sq mi (740/km2) |

| Demonyms | Montgomery Countyan, MoCoite |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern [EST]) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 20812–20918 |

| Area codes | |

| Seat (and largest city) | |

| Congressional districts | Maryland's [5] |

| Website | www |

As one of the most affluent counties in the United States,[8] Montgomery County also has the highest percentage (29.2%) of residents over 25 years of age who hold post-graduate degrees.[9] The county has been ranked as one of the wealthiest in the United States.[10][11] Like other inner-suburban Washington, D.C. counties, Montgomery County contains many major U.S. government offices, scientific research and learning centers, and business campuses, which provide a significant amount of revenue for the county.[12][13]

Etymology

The Maryland state legislature named Montgomery County after Richard Montgomery; the county was created from lands that had at one point or another been part of Frederick County.[14] On September 6, 1776,[3] Thomas Sprigg Wootton from Rockville, Maryland, introduced legislation, while serving at the Maryland Constitutional Convention, to create lower Frederick County as Montgomery County. The name, Montgomery County, along with the founding of Washington County, Maryland, after George Washington, was the first time in American history that counties and provinces in the thirteen colonies were not named after British referents. The name use of Montgomery and Washington County were seen as further defiance to Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. The county's nickname of "MoCo" is derived from "Montgomery County".[15][16]

The county's motto, adopted in 1976, is "Gardez Bien", a phrase meaning "Watch Well". The county's motto is also the motto of its namesake's family.[17][18][19]

History

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

Early history

Before European colonization, the land now known as Montgomery County was covered in a vast swath of forest crossed by the creeks and small streams that feed the Potomac and Patuxent rivers. A few small villages of the Piscataway, members of the Algonquian people, were scattered across the southern portions of the county. North of the Great Falls of the Potomac, there were few permanent settlements, and the Piscataway shared hunting camps and foot paths with members of rival peoples like the Susquehannocks and the Senecas.

Captain John Smith of the English settlement at Jamestown was probably the first European to explore the area, during his travels along the Potomac River and throughout the Chesapeake region.[20]

These lands were claimed by Europeans for the first time when George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore was granted the charter for the colony of Maryland by Charles I of England.[21] However, it was not until 1688 that the first tract of land in what is now Montgomery County was granted by the Calvert family to an individual colonist, a wealthy and prominent early Marylander named Henry Darnall. He and other early claimants had no intention of settling their families. They were little more than speculators, securing grants from the colonial leadership and then selling their lands in pieces to settlers. Thus, it was not until approximately 1715 that the first British settlers began building farms and plantations in the area.[22]

These earliest settlers were English or Scottish immigrants from other portions of Maryland, German settlers moving down from Pennsylvania, or Quakers who came to settle on land granted to a convert named James Brooke in what is now Brookeville. Most of these early settlers were small farmers, growing wheat and a variety of other subsistence crops in addition to the region's main cash crop, tobacco. Many of the farmers owned slaves. They transported the tobacco they grew to market through the Potomac River port of Georgetown.[23] Sparsely settled, the area's farms and taverns were nonetheless of strategic importance as access to the interior. General Edward Braddock's army traveled through the county on the way to its disastrous defeat at Fort Duquesne during the French and Indian War.[24]

Like other regions of the American colonies, the region that is now Montgomery County saw protests against British taxation in the years before the American Revolution. In 1774, local residents met at Hungerford's Tavern and agreed to break off commerce with Great Britain.[25] Following the signing of the Declaration of Independence, representatives of the area helped to draft the new state constitution and began to build a Maryland free of proprietary control.[26]

Founding

By 1776, there was a growing movement to form a new, strong federal government, with each colony retaining the authority to govern its local affairs.[27] Member of the Maryland Constitutional Convention Thomas S. Wootton thought that dividing large Frederick County into three counties, each governed by elected representatives, would result in greater self-government.[27]

When Wootton discussed his idea with the residents of southern Frederick County, the residents supported his idea for a different reason.[27] At some point, almost everyone had needed to travel to the courthouse in Frederick Town, and the travel cost and time was prohibitive.[27] The residents wanted a county courthouse to be located closer to them.[27]

On August 31, 1776, Wootton introduced a measure to form a new county from the southern portion of Frederick County.[27]

Resolved, That after the first day of October, next, such part of the said county of Frederick as is contained within the bounds and limits following, to wit: beginning at the east side of the mouth of Rock Creek, on the Potomac River, and running thence with the said river to the mouth of Monocacy, then with a straight line to Parr's Spring, from thence with the lines of the county to the beginning shall be and is hereby erected into a new county called Montgomery County.[27]

Wootton proposed naming the new county after the well-known Major General Richard Montgomery, who had served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War.[27][28] Eight months prior, Montgomery had died in Quebec City while attempting an ultimately unsuccessful invasion of the Province of Quebec.[27] Montgomery had never actually set foot on the land that would bear his name.[27]

Wootton also proposed forming a new county from the northwestern portion of Frederick County, named Washington County, named after another well-known leader of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, General George Washington.[27]

Several members of the Maryland Continental Convention opposed Wootton's proposal, and it was tabled.[27] Six days later, Wootton pressed for his proposal again, and it passed by a slim majority. As a result, Montgomery County came into existence on October 1, 1776.[27]

In 1777, the leaders of the new county chose as their county seat an area adjacent to Hungerford's Tavern near the center of the county, which became Rockville in 1801.[29][30] When deciding its name, the original idea was to call it Wattsville, after Watts Branch, a stream that runs through the land.[30] Because Watts Branch is a small stream, the idea was reconsidered, and the area was ultimately named Rockville after the nearby and larger Rock Creek.[30]

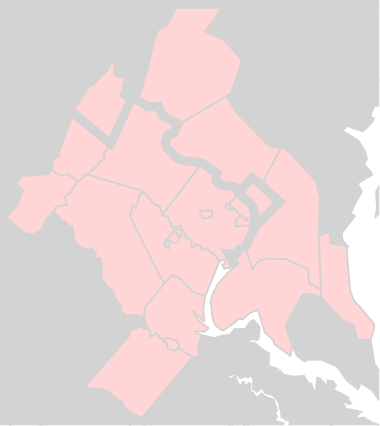

For tax purposes, Montgomery County was divided into eleven districts, called hundreds.[31] The names and areas of each hundred carried over from when the area was still part of Frederick County.[31] The eleven districts were named as follows.

- Linganor Hundred (now Clarksburg, Damascus, and Hyattstown);

- Upper Newfoundland Hundred (Brookeville, Laytonsville, Olney, Sandy Spring);

- Lower Newfoundland Hundred (Ashton, Brighton, Burtonsville);

- Rock Creek Hundred (Colesville, Layhill, Norbeck);

- Northwest Hundred (Kensington, Wheaton, Silver Spring, Takoma Park);

- Lower Potomac Hundred (Bethesda, Chevy Chase, Georgetown);

- Middle Potomac Hundred (Potomac, Rockville);

- Upper Potomac Hundred (Darnestown, Dawsonville, Seneca);

- Seneca Hundred (Gaithersburg);

- Sugar Loaf Hundred (Barnesville, Beallsville, Germantown);

- Sugarland Hundred (Poolesville).[31]

The first court was held at Hungerford's Tavern on May 20, 1777.[30] Court was held by Charles Jones, Samuel W. Magruder, Elisha Williams, William Deakins, Richard Thompson, James Offutt, and Edward Burgess, with Brook Beall as clerk.[30] Clement Beall served as the county's first sheriff.[30] The county's first courthouse was built soon thereafter, and the court was held at the new courthouse beginning in 1779.[30]

According to the 1790 census, the county's first, 18,000 people lived in the county, of which about 35 percent were black.[31]

Montgomery County supplied arms, food, and forage for the Continental Army during the Revolution, in addition to soldiers.[32]

In 1791, portions of Montgomery County, including Georgetown, were ceded to form the new District of Columbia, along with portions of Prince George's County, Maryland, as well as parts of Virginia that were later returned to Virginia.

19th century

In 1828, construction on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal commenced and was completed in 1850. Laborers were primarily Irish immigrants.[33] Throughout the 19th century, agriculture dominated the economy in Montgomery County, with slaves playing a significant role, though the vast majority of farmers owned 10 slaves or less rather than large plantations.[34] In the first half of the 19th century, low tobacco prices and worn-out soil caused many tobacco farms to be abandoned.[35] Crop production gradually shifted away from tobacco and toward wheat and corn. Prior to the Civil War, Montgomery County allied itself with other slaveholding counties in southern Maryland and the Eastern Shore.[33] Montgomery County was important in the abolitionist movement, especially among the Quakers in the northern part of the county near Sandy Spring.[36] Josiah Henson grew up as a slave on the Riley farm south of Rockville.[37] He wrote about his experiences in a memoir which became the basis for Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). A slave cabin where he is believed to have spent time still stands at the end of a driveway off Old Georgetown Road.

Until 1860, only private schools existed in Montgomery County. Initially, schools for European American students were built. A school in Rockville for free African-Americans existed until 1866.[38] Another school for African-Americans was opened by 1877 in Rockville.[39]

Montgomery County's proximity to the nation's capital and split sympathies to North and South resulted in it being occupied by Union forces during the Civil War. The county was "invaded" on multiple occasions by Confederate and Union forces.[40]

In 1855, work on the Metropolitan Branch of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad began, in order to provide a route between Washington, D.C., and Point of Rocks, Maryland.[41] In 1873, the railroad opened. The railroad spurred development at Takoma Park, Kensington, Garrett Park and Chevy Chase. By providing a much-needed transportation link, it also greatly increased the value of farmland and spurred the development of a dairy industry in the county.[42]

During the Jim Crow era, masked mobs of local white men carried out two separate lynchings of African-American men in Montgomery County on Rockville's courthouse lawn. John Diggs was violently lynched in 1880 and Sydney Randolph similarly murdered in 1896.[43][44] Neither man was found guilty in a court of law, nor was anyone punished for the lynchings. On that same lawn, the Maryland Historical Society maintains a monument to the Confederate army as "heroes of the thin grey line",[45][46] because Montgomery County, like the rest of Maryland, was divided over the issue of secession.[47] One vocal sociologist has claimed Montgomery County was not welcoming of the Confederates during the Civil War.[48][49] No memorial exists for victims of Montgomery County's lynchings.

20th and 21st centuries

On July 1, 1922, the Montgomery County Police Department was established.[50] Prior to that time, law enforcement duties rested in the Montgomery County Sheriff and designated constables.[51] In 1922, the police department consisted of three to six officers who were appointed to two-year terms by the Board of County Commissioners, one of whom would be appointed as Chief.[51] In 1927, the police department was enlarged to twenty officers.[51]

The remains of author F. Scott Fitzgerald, best known for the novel The Great Gatsby, are interred at St. Mary’s Catholic Church Cemetery in Rockville.[52]

Home rule

The county began with most legislative power in the hands of the Maryland state government, with a five-person Montgomery County Board of Commissioners who oversaw the administration of the county but could neither pass county laws nor enact policies.[53]

In 1915, Maryland amended its constitution.[53] According to the constitutional amendment,[54] a county's residents may propose a petition to create a nonpartisan Charter Board.[53] If the petition receives signatures from at least twenty percent of the county's registered voters, all county residents would vote to select the members of the Charter Board during the next general election.[53] The Charter Board would be authorized to draft a new system of county government, which could include a county council with the power to enact legislation and policies.[53] The Charter Board's proposal would then be voted upon by registered voters during the following general election, and it would be enacted if approved by the voters.[53]

In 1930, two-thirds of Arlington County, Virginia residents voted to appoint a county manager,[55] inspiring activists in Montgomery County to advocate for the same.[56] In 1935, a group of farmers meeting in Sandy Spring decided that Montgomery County needed a new form of governance.[56] The farmers were in favor of a professional county manager and a home-rule charter for Montgomery County.[56]

In 1936, the Montgomery County Civic Federation announced its support for a home-rule charter, a merit system for Montgomery County's employees, and a comptroller to administer the county's finances.[56] The following year, the Montgomery County Civic Federation appointed Woodside Park-resident Allen H. Gardener to head a committee to study the reorganization of the Montgomery County's government.[56] The committee recommended massive changes and, in February 1938, the Montgomery County Civic Federation passed a resolution urging the Montgomery County commissioners to engage a professional group to study the county's government.[56]

In October 1938, the Montgomery County Commissioners held a public hearing on the proposal.[56] The Commissioners decided to authorize a study of the existing county government structure with the goal of suggesting recommendations.[56] In November 1938, the Commissioners selected the Brookings Institution for Government Research to conduct the study.[57] The 720-page report opined that the county had outgrown its form of government.[58]

The Brookings Institution's study recommended the creation of a nonpartisan county council consisting of nine members representing defined districts of the county who could pass legislation, determine policy, and control over the administration of the county.[58] The county should hire a county administrator, create an independent comptroller in charge of county finances, consolidate welfare services, and establish a three-member non-political civil service commission.[56][58] Black children deserved better schools, and all children should receive military training and learn about democracy.[56] The Liquor Control Board should be abolished, and the county should hire a full-time attorney rather than retain multiple part-time legal advisers.[56] A professional consultant should reassess taxes, and the tax rate should be increased enough to retire the county's debt.[56] The Montgomery County Civic Federation praised the study for its comprehensiveness.[59]

The county commissioners appointed a citizen's committee to determine how to enact the study's recommendations.[60] The county commissioners strongly criticized the recommendation to create a county council, both because the council would be nonpartisan and because each county resident would be able to vote for only one representative rather than for all nine.[60] Implementing some of the recommendations weeks later, the county commissioners appointed a permanent Board of Assessors, reorganized the Welfare Board, hired the a County Attorney and a purchasing agent, and hired sixteen police officers.

In 1942, Montgomery County Charter Committee was organized, which was formed primarily to circulate petitions to form a Charter Board.[61] The Charter Board petitioned to form a county council with the power to pass laws without the consent of the Maryland General Assembly and with authority over the administration the county.[62] While the Democratic Party did not explicitly denounce the charter,[63] it issued a statement calling out the ostensibly nonpartisan movement for hidden partisan goals[64] and claimed that backers of the charter petition for their alleged personal and political attacks on the Democratic Party and its officials.[65] The newly formed Independent Party endorsed the charter, praising county residents' goal of improving their form of government.[66] In the November 1942 election, county residents voted in favor of forming a Charter Board.[67]

In 1943, the Charter Board released its draft charter.[68] The council would have nine unpaid members,[69] of which five would represent each of five single-member districts and four would represent the county at-large.[68] Council seats would be nonpartisan, each seat would be held for four years, and elections would occur every two years.[68] The council would have the power to enact legislation and hire a county manager, to whom all governmental department heads would report.[68] All sessions of the council would be open to the public.[68] The office of county treasurer would be abolished and replaced by a director of finance, who would be responsible for assessment and collection of taxes, assessments, and licenses, custody and disbursement of public funds and property, and preparation of monthly financial statements.[68] A department of public works, department of education, department of safety, department of welfare, and department of health would also be created.[68]

The Montgomery County Charter Board opened its campaign headquarters in Bethesda, to serve as an information center regarding the draft charter.[70] The Charter Board emphasized that the draft charter would allow for county affairs to be decided by local representatives rather than by a vote of members of the Maryland General Assembly who represent citizens of all parts of the state.[70] Another group opposing the draft charter opened its headquarters in Bethesda.[69] The group said there was no good reason to abolish the functional state-level system already in place, and that the draft charter would increase taxes and establish heads of governmental agencies with indefinite terms who are not directly accountable to the public.[69] The group also said that making the council seats nonpartisan would go against the country's political history.[69] The editorial board of The Washington Post supported the draft charter.[71] The Montgomery County League of Women Voters also endorsed the draft charter.[72]

In a near-record turnout,[73] a 1946 vote to enact a home-rule charter failed by a vote of 14,471 to 13,270.[74] Following the vote, proponents of the charter said they would not give up the fight.[75]

Several months later, Montgomery County Democratic Party leader Col. E. Brooke Lee said he would support Montgomery County home rule by way of an act of the Maryland state legislature.[75] Lee proposed a bill to create a position of county supervisor, who would be in charge of routine county business, would appoint county employees subject to civil service rules and regulations, would supervise expenditures, and would prepare the operating and capital budgets.[76] The bill did not disband the county commissioners or create a county council.[76] The bill passed the state legislature and was signed by Governor Herbert R. O'Conor in 1945.[76] The county commissioners appointed Willard F. Day to the position.[76]

In 1948, by a vote of 17,809 in favor and 13,752 against, voters approved a charter for a "Council-Manager" form of government, making Montgomery County the first home-rule county in Maryland.[77] The charter created an elected seven-member County Council with the power to pass local laws.[77] All seven Council Members would be elected at-large by all county residents.[78] Five would have to live in five different residence districts, while the other two could live anywhere within the county.[78] The Council would serve as both the legislative and executive functions of the county.[79] Council members would elect one of their own to serve as president of the Council.[79] The charter also authorized the hiring of a county manager, the top administrative official,[80] who could be dismissed by the Council after a public hearing.[81] The charter created a department of public works, department of finance, and office of the county attorney, while it abolished the positions of county treasurer and police commissioner.[81] The first County Council was elected in 1949.[80]

County executive

In 1962, a county civic group advocated for the election of a county executive.[82] The group's report said that the new position would give citizens another place to go if their concerns were refused by the Montgomery County Council.[82] The group said that the fact that the county had four appointed county managers in thirteen years demonstrates that establishing the position in 1948 had not been a stunning success.[82] The group also advocated for nonpartisan elections for council members.[83] Among the reasons for the suggested changes in governance is the fact that the county's population had more than doubled since the governmental system had been established in 1948.[82]

In 1966, the Montgomery County Council adopted a proposed charter amendment to create a new elected position of County Executive.[84] Elected to a four-year term, the County Executive could veto legislation passed by the County Council, although five members of the County Council could vote to overrule the veto.[84] All Council Members would continue to be at-large, but they would need to live in seven different residence districts.[84] Republicans favored a referendum on the proposed charter amendment, while Democrats favored it in principle but urged the specific amendment's defeat because the duties of the County Executive were not specific enough.[85][86] In the referendum held in September 1966,[87] the referendum was defeated, with 57 percent of voters opposed.[88]

In February 1967, the Montgomery County Council formed a commission to draft a charter amendment to elect a county executive.[89] The commission's plan was to separate the legislative and executive functions of government.[79] The county council would continue to be the legislative branch of county government, and an elected full-time County Executive who could veto legislation passed by the Council; it would take five votes by the Council to override a veto.[90] The County Executive would hire a chief administrative officer to supervise the daily operations of the government.[90] All Council Members would be elected at-large by all county residents, but five of the seven would need to live in each of five different residential districts of substantially equal population.[90] In November 1968, the charter amendment was approved, with 53 percent of votes in favor.[91]

In the first election for County Executive, held in 1970,[91] Republican James P. Gleason defeated Democrat William W. Greenhalgh by a margin of 420 votes.[92]

In November 1986, voters amended the Charter to increase the number of Council seats in the 1990 election from seven to nine. Now five members are elected by the voters of their council district and four are elected at-large. Each voter may vote for five council members; four at-large and one from the district in which they reside.[93]

Annexation

In November 1995, the City of Takoma Park held a state-sponsored referendum asking whether the portions of the city in Prince George's County should be annexed to Montgomery County or vice versa. The majority of votes in the referendum were in favor of unification of the entire city in Montgomery County.[94] Following subsequent approval by both counties' councils and the Maryland General Assembly, the county line was moved to include the entire city into Montgomery County (including territory in Prince George's County newly annexed by the city) on July 1, 1997.[95] This added about 800 residents to Montgomery County's population.[96]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 507 square miles (1,310 km2), of which 491 square miles (1,270 km2) is land and 16 square miles (41 km2) (3.1%) is water.[98] Montgomery County lies entirely inside the Piedmont plateau. The topography is generally rolling. Elevations range from a low of near sea level along the Potomac River to about 875 feet in the northernmost portion of the county north of Damascus. Relief between valley bottoms and hilltops is several hundred feet.

When Montgomery County was created in 1776, its boundaries were defined as "beginning at the east side of the mouth of Rock Creek on Potowmac river [sic], and running with the said river to the mouth of Monocacy, then with a straight line to Par's spring, from thence with the lines of the county to the beginning".[4]

The county's boundary forms a sliver of land at the far northern tip of the county that is several miles long and averages less than 200 yards wide. In fact, a single house on Lakeview Drive and its yard is sectioned by this sliver into 3 portions, each separately contained within Montgomery, Frederick and Howard Counties. These jurisdictions and Carroll County meet at a single point at Parr's Spring on Parr's Ridge.

Adjacent counties

- Frederick County (northwest)

- Carroll County (north)

- Howard County (northeast)

- Prince George's County (southeast)

- Washington, D.C. (south)

- Fairfax County, Virginia (southwest)

- Loudoun County, Virginia (west)

National protected areas

- Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park (part)

- Clara Barton National Historic Site

- George Washington Memorial Parkway (part)

Climate

Montgomery County lies within the northern portions of the humid subtropical climate. It has four distinct seasons, including hot, humid summers and cool winters.

Precipitation is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year, with an average of 43 inches (110 cm) of rainfall.[99] Thunderstorms are common during the summer months, and account for the majority of the average 35 days with thunder per year. Heavy precipitation is most common in summer thunderstorms, but drought periods are more likely during these months because summer precipitation is more variable than winter.

The mean annual temperature is 55 °F (13 °C). The average summer (June–July–August) afternoon maximum is about 85 °F (29 °C) while the morning minimums average 66 °F (19 °C). In winter (December–January–February), these averages are 44 °F (7 °C) and 28 °F (−2 °C). Extreme heat waves can raise readings to around and slightly above 100 °F (38 °C), and arctic blasts can drop lows to −10 °F (−23 °C) to 0 °F (−18 °C). For Rockville, the record high is 105 °F (41 °C) in 1954, while the record low is −13 °F (−25 °C).[99]

Lower elevations in the south, such as Silver Spring, receive an average of 17.5 inches (44 cm) of snowfall per year.[100] Higher elevations in the north, such as Damascus,[101] receive an average of 21.3 inches (54 cm) of snowfall per year.[102] During a particularly snowy winter, Damascus received 79 inches (200 cm) during the 2009–2010 season.[103]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 18,003 | — | |

| 1800 | 15,058 | −16.4% | |

| 1810 | 17,980 | 19.4% | |

| 1820 | 16,400 | −8.8% | |

| 1830 | 19,816 | 20.8% | |

| 1840 | 15,456 | −22.0% | |

| 1850 | 15,860 | 2.6% | |

| 1860 | 18,322 | 15.5% | |

| 1870 | 20,563 | 12.2% | |

| 1880 | 24,759 | 20.4% | |

| 1890 | 27,185 | 9.8% | |

| 1900 | 30,451 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 32,089 | 5.4% | |

| 1920 | 34,921 | 8.8% | |

| 1930 | 49,206 | 40.9% | |

| 1940 | 83,912 | 70.5% | |

| 1950 | 164,401 | 95.9% | |

| 1960 | 340,928 | 107.4% | |

| 1970 | 522,809 | 53.3% | |

| 1980 | 579,053 | 10.8% | |

| 1990 | 757,027 | 30.7% | |

| 2000 | 873,341 | 15.4% | |

| 2010 | 971,777 | 11.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 1,050,688 | [6] | 8.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[104] 1790–1960[105] 1900–1990[106] 1990–2000[107] 2010–2018[6] | |||

Since the 1970s, the county has had in place a Moderately Priced Dwelling Unit (MPDU) zoning plan that requires developers to include affordable housing in any new residential developments that they construct in the county. The goal is to create socioeconomically mixed neighborhoods and schools so the rich and poor are not isolated in separate parts of the county. Developers who provide for more than the minimum amount of MPDUs are rewarded with permission to increase the density of their developments, which allows them to build more housing and generate more revenue. Montgomery County was one of the first counties in the U.S. to adopt such a plan, but many other areas have since followed suit.

2000 census

As of the 2000 United States Census, there were 873,058 people living in the county. The racial makeup of the county was 65.0% white, 15.1% black or African American, 11.3% Asian, 0.3% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 5.0% from other races, and 3.5% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 11.5% of the population.[108]

There were 324,565 households of which 35% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.2% were married couples living together, 10.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.9% were non-families. 24.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.19.

25.4% of the population was under the age of 18, 6.9% from 18 to 24, 32.3% from 25 to 44, 24.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.1 males.

In 2000, there were 334,632 housing units at an average density of 675 per square mile (261/km2).

Montgomery County has the tenth highest median household income in the United States, and the second highest in the state after Howard County as of 2011. The median household income in 2007 was $89,284 and the median family income was $106,093. Males had a median income of $66,415 versus $52,134 for females. The per capita income for the county was $43,073. About 3.3% of families and 4.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.6% of those under age 18 and 4.6% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 971,777 people, 357,086 households, and 244,898 families living in the county.[109][110] The population density was 1,978.2 inhabitants per square mile (763.8/km2). There were 375,905 housing units at an average density of 765.2 per square mile (295.4/km2).[111] The racial makeup of the county was 57.5% white, 17.2% black or African American, 13.9% Asian, 0.4% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 7.0% from other races, and 4.0% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 17.0% of the population.[109] In terms of ancestry, 10.7% were German, 9.6% were Irish, 7.9% were English, 4.9% were Italian, 3.5% were Russian, 3.1% were Polish, 2.9% were American and 2% were French.[112] 8.1% of Montgomery County was of Central American descent, with Salvadoran Americans constituting 5.4% of the county's population. Over 52,000 people of Salvadoran descent lived in Montgomery County, with Salvadoran Americans comprising approximately 32% of the county's Hispanic and Latino population. 3.8% of the county is of South American descent, with Peruvian Americans being the largest South American community constituting 1.2% of the county's population.[113]

Of the 357,086 households, 35.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.4% were married couples living together, 11.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 31.4% were non-families, and 25.0% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.22. The median age was 38.5 years.[109]

The median income for a household in the county was $93,373 and the median income for a family was $111,737. Males had a median income of $71,841 versus $55,431 for females. The per capita income for the county was $47,310. About 4.0% of families and 6.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.2% of those under age 18 and 6.3% of those age 65 or over.[114]

2014 estimates

The United States Census Bureau estimated the county's population was 1,030,447 as of 2014.[115] If it were a city, it would be the tenth most populous city in the U.S. after San Jose, California and Austin, Texas.

The ethnic makeup of the county was estimated to be the following in 2013:[115]

- 62.6% White (47.0% Non-Hispanic White)

- 18.6% Black

- 14.9% Asian

- 0.7% Native American

- 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- 3.1% Two or more races

In addition, 18.3% were Hispanic or Latino, of any race.[115]

People who were born on continent of Africa are 6% of the county's total residents. The plurality of these were born in Ethiopia.[116] People from China are the fastest-growing immigrant population in the county; people from Ethiopia are the county's second-fastest growing immigrant population.[116]

2016 estimates

The United States Census Bureau estimated the county's population as 1,043,863 as of 2016.[117]

The race and Hispanic original of the county's residents was estimated to be the following as of 2016:[117]

- 60.9% White (44.7% Non-Hispanic White)

- 19.5% Black

- 15.5% Asian

- 0.7% Native American

- 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- 3.4% Two or more races

In addition, 19.1% were Hispanic or Latino, of any race.[117]

Of residents age 25 or older, 91.2% have graduated high school, and 57.1% had a bachelor's degree.[117]

Of the county's population, 32.6% were born outside the United States.[118]

44,718 veterans lived in the county in 2016.[117]

Of residents age 5 or older, 39.8% spoke a language other than English at home in 2016.[117]

2018 estimates

As of July 1, 2018 The United States Census Bureau estimates the population of the county to be, 1,052,567 residents.[119]

The race and Hispanic origin of the county's residents are estimated to be:[119]

- 60.2% White (43.4% Non-Hispanic White)

- 19.9% African-American or Black

- 19.9% Hispanic or Latino

- 15.6% Asian

- 3.4% Two or more races

- 0.7% American Indian or Alaskan Native

- 0.1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

The Age and Sex is estimated to be:[119]

- 6.3% Persons under 5 years

- 23.3% Persons under 18 years

- 15.5% Persons 65 years and over

- 51.6 Female Persons

With the amount of housing units estimated to be 390,664.

Religion

Of Montgomery County's residents, 14% are Catholic, 5% are Baptist, 3% are Methodist, 1% are Presbyterian, 1% are Episcopalian, 1% are part of the Latter Day Saint movement, 1% are Lutheran, 6% are of another Christian faith, 3% are Jewish, 1% follows Islam, and 1% are of an eastern faith.[120] Overall, 41% of the county's residents are affiliated with a religion.[120]

Montgomery County has the largest Jewish population in the state of Maryland, accounting for 45% of Maryland Jews. According to the Berman Jewish DataBank, Montgomery County has a Jewish population of 105,400 people, around 10% of the county's population.[121] The Greater Washington area, with 295,500 Jews, has become the third largest Jewish population in the United States.[122]

Economy

Montgomery County is an important business and research center. It is the epicenter for biotechnology in the Mid-Atlantic region. Montgomery County, as third largest biotechnology cluster in the U.S., holds a large cluster and companies of large corporate size within the state. Biomedical research is carried out by institutions including Johns Hopkins University's Montgomery County Campus (JHU MCC), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). Federal government agencies in Montgomery County engaged in related work include the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Many large firms are based in the county, including Coventry Health Care, Lockheed Martin, Marriott International, Host Hotels & Resorts, Travel Channel, Ritz-Carlton, Robert Louis Johnson Companies (RLJ Companies), Choice Hotels, MedImmune, TV One, BAE Systems Inc, Hughes Network Systems and GEICO.

Other U.S. federal government agencies based in the county include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Downtown Bethesda and Silver Spring are the largest urban business hubs in the county; combined, they rival many major city cores.

Top employers

According to the county's comprehensive annual financial reports, the top employers by number of employees in the county are the following. "NA" indicates not in the top ten employers for the year given.

| Employer | Employees (2014)[123] |

Employees (2011)[124] |

Employees (2005)[123] |

|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | 28,500 | 29,700 | 38,800 |

| Montgomery County Public Schools | 25,429 | 22,016 | 20,987 |

| U.S. Department of Defense | 12,000 | 12,690 | 13,800 |

| County of Montgomery | 10,815 | 8,849 | 8,272 |

| U.S. Department of Commerce | 5,500 | 8,250 | 6,200 |

| Adventist Healthcare | 4,900 | 5,310 | 6,000 |

| Marriott International (headquarters) | 4,700 | 5,441 | NA |

| Lockheed Martin | 4,000 | 4,745 | 3,900 |

| Montgomery College | 3,632 | NA | NA |

| Holy Cross Hospital of Silver Spring | 3,400 | NA | NA |

| Nuclear Regulatory Commission | 3,840 | NA | NA |

| Giant | NA | 3,842 | 4,900 |

| Verizon | NA | 3,292 | 4,700 |

| Chevy Chase Bank | NA | NA | 4,700 |

Government

.jpg)

Montgomery County was granted a charter form of government in 1948.

The present County Executive/County Council form of government of Montgomery County dates to November 1968 when the voters changed the form of government from a County Commission/County Manager system, as provided in the original 1948 home rule Charter.

The Montgomery County Police Department provides county-wide law enforcement services, although several cities including Rockville and Gaithersburg maintain their own police departments to complement MCPD. Maryland State Police patrol Interstate highways 495 (the "Beltway") and 270 and assist county and city police in investigation of some major crimes.

County executives

The office of the county executive was established in 1970. The first executive was James P. Gleason. The current executive is Marc Elrich, who was sworn in for his first term on December 3, 2018.[125]

| Position | Name | Party | Term | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | James Gleason | Republican | 1970–1978 | |

| 2nd | Charles Gilchrist | Democratic | 1978–1986 | |

| 3rd | Sidney Kramer | Democratic | 1986–1990 | |

| 4th | Neal Potter | Democratic | 1990–1994 | |

| 5th | Doug Duncan | Democratic | 1994–2006 | |

| 6th | Ike Leggett | Democratic | 2006–2018 | |

| 7th | Marc Elrich | Democratic | 2018- | |

Legislative body

- See also Montgomery County Council (Maryland).

The members of the County Council as of 2018 are:[126]

| Position | Name | Affiliation | District | First Elected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Member | Andrew Friedson | Democratic | 1: Poolesville/Potomac/Bethesda/Chevy Chase | 2018 | |

| President | Craig L. Rice | Democratic | 2: Germantown/Clarksburg/Darnestown/Damascus | 2010 | |

| Member | Sidney A. Katz | Democratic | 3: Gaithersburg/Rockville | 2014 | |

| Member | Nancy Navarro | Democratic | 4: Wheaton/Glenmont/Aspen Hill/Ashton/Laytonsville | 2009 | |

| Member | Tom Hucker | Democratic | 5: Silver Spring/Takoma Park/Burtonsville | 2014 | |

| Member | Gabe Albornoz | Democratic | At-Large | 2018 | |

| Member | Evan Glass | Democratic | At-Large | 2018 | |

| Member | Will Jawando | Democratic | At-Large | 2018 | |

| Member | Hans Riemer | Democratic | At-Large | 2010 | |

The last Republican serving on the Montgomery County Council, Howard A. Denis of District 1 (Potomac/Bethesda), was defeated in 2006. The board has since been all-Democratic.

Budget

Montgomery County has a budget of $2.3 billion. Approximately $1.48 billion are invested in Montgomery County Public Schools and $128 million in Montgomery College.[127]

Bi-county agencies

Montgomery and Prince George's Counties share a bi-county planning and parks agency in the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (often referred to as Park and Planning or its initials M-NCPPC by county residents) and a public bi-county water and sewer utility in the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC).

Liquor control

Montgomery County is an alcoholic beverage control county. Beer and wine may still be sold in individual stores and at a single location within the county for a store chain.

History

Until 1964, only three restaurants in the county had liquor licenses to serve liquor by the drink.[128] The county stopped issuing liquor licenses to all other restaurants under a law that had existed since Prohibition.[129]

Following a voter referendum,[130] restaurants and bars could apply for county permits to sell liquor by the drink.[129] The dry towns of Kensington, Poolesville, and Takoma Park were allowed to keep their own bans in place.[129]

Anchor Inn in Wheaton was the first establishment to serve liquor in the county under the new law.[128]

Federal representation

In the 116th Congress, Montgomery is represented in the U.S. House of Representatives by John Sarbanes of the 3rd district, David Trone of the 6th district, and Jamie Raskin of the 8th district.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 19.4% 92,704 | 74.7% 357,837 | 5.9% 28,332 |

| 2012 | 27.1% 123,353 | 70.9% 323,400 | 2.0% 9,239 |

| 2008 | 27.0% 118,608 | 71.6% 314,444 | 1.4% 6,209 |

| 2004 | 32.8% 136,334 | 66.0% 273,936 | 1.2% 4,955 |

| 2000 | 33.5% 124,580 | 62.5% 232,453 | 3.9% 14,655 |

| 1996 | 35.2% 117,730 | 59.4% 198,807 | 5.5% 18,361 |

| 1992 | 33.0% 119,705 | 55.1% 199,757 | 11.9% 43,151 |

| 1988 | 48.1% 154,191 | 51.5% 165,187 | 0.5% 1,518 |

| 1984 | 50.0% 146,924 | 49.7% 146,036 | 0.3% 910 |

| 1980 | 47.2% 125,515 | 39.8% 105,822 | 13.1% 34,814 |

| 1976 | 48.3% 122,674 | 51.7% 131,098 | |

| 1972 | 56.5% 133,090 | 42.6% 100,228 | 1.0% 2,239 |

| 1968 | 44.2% 84,651 | 48.1% 92,026 | 7.7% 14,726 |

| 1964 | 33.8% 52,554 | 66.2% 103,113 | |

| 1960 | 48.7% 62,679 | 51.3% 66,025 | |

| 1956 | 57.0% 56,501 | 43.0% 42,606 | |

| 1952 | 62.4% 47,805 | 37.0% 28,381 | 0.6% 467 |

| 1948 | 60.3% 23,174 | 37.3% 14,336 | 2.3% 897 |

| 1944 | 57.1% 20,400 | 42.9% 15,324 | |

| 1940 | 46.9% 13,831 | 51.4% 15,177 | 1.7% 513 |

| 1936 | 43.1% 10,133 | 56.3% 13,246 | 0.7% 153 |

| 1932 | 36.2% 5,698 | 62.7% 9,882 | 1.2% 183 |

| 1928 | 57.7% 9,318 | 41.8% 6,739 | 0.5% 82 |

| 1924 | 44.0% 5,675 | 51.5% 6,639 | 4.5% 580 |

| 1920 | 48.0% 5,948 | 50.6% 6,277 | 1.4% 177 |

| 1916 | 42.5% 2,913 | 55.5% 3,805 | 2.0% 136 |

| 1912 | 26.8% 1,675 | 56.1% 3,501 | 17.1% 1,065 |

| 1908 | 44.7% 2,805 | 53.4% 3,351 | 1.9% 119 |

| 1904 | 46.1% 2,711 | 52.4% 3,082 | 1.5% 89 |

| 1900 | 46.9% 3,354 | 51.4% 3,677 | 1.7% 120 |

Transportation

Roads

_from_the_overpass_for_West_Gude_Drive_in_Rockville%2C_Montgomery_County%2C_Maryland.jpg)

Poor transportation was a hindrance for Montgomery County's farmers who wanted to transport their crops to market in the early 18th century. Montgomery County's first roads, often barely adequate, were built by the 18th century.

One early road connected Frederick and Georgetown. There was a road that connected Georgetown and the mouth of the Monocacy River. Plans to continue the road to Cumberland did not come to fruition. Another road connected the Montgomery County Courthouse with Sandy Spring and Baltimore, and one other road connected the courthouse with Bladensburg and Annapolis.[31][132]

The county's first turnpike was chartered in 1806, but its construction began in 1817. In 1828, the turnpike was completed, running from Georgetown to Rockville. It was the first paved road in Montgomery County.[31][132]

In 1849, the Seventh Street Turnpike (now called Georgia Avenue) was extended from Washington to Brookeville. The Colesville–Ashton Turnpike was built in 1870 (now parts of Colesville Road, Columbia Pike, and New Hampshire Avenue).[132]

The United States Army Corps of Engineers built the Washington Aqueduct between 1853 and 1864, to supply water from Great Falls to Washington. The aqueduct was covered in 1875, and it became known as Conduit Road. The Union Arch Bridge, which carries the aqueduct across Cabin John Creek, was the longest single-arch bridge in the world at the time it was completed in 1864. The road is now named MacArthur Boulevard.[31][132]

Major Highways and Roads

Bus

Montgomery County operates its own bus public transit system, known as Ride On.[133] Major routes closer to its rail service area are also covered by WMATA's Metrobus service.[134]

The county began building a bus rapid transit (BRT) system along US 29 in 2018. The system will provide service between Silver Spring and Burtonsville and is scheduled to begin operation in 2020.[135][136]

The Corridor Cities Transitway is a proposed BRT line that would provide an extension of the Red Line corridor from Gaithersburg to Germantown, and eventually to Frederick County.[137]

Rail

Montgomery County is served by three passenger rail systems, with a fourth line under construction.

Amtrak, the U.S. national passenger rail system, operates its Capitol Limited to Rockville, between Washington Union Station and Chicago Union Station.

The Brunswick line of the MARC commuter rail system makes stops at Silver Spring, Kensington, Garrett Park, Rockville, Washington Grove, Gaithersburg, Metropolitan Grove, Germantown, Boyds, Barnesville, and Dickerson, where the line splits into its Frederick and Martinsburg branches.

Both suburban arms of the Red Line of the Washington Metro serve Montgomery County. It follows the CSX right of way to the west, roughly paralleling Route 355 from Friendship Heights to Shady Grove. The eastern side runs between the two tracks of the CSX right of way from Washington Union Station to Silver Spring, and roughly parallels Georgia Avenue, from Silver Spring to Glenmont.

The Purple Line, a light rail system, is currently under construction and is scheduled to open in 2022.[138] The line will run in a generally east-west direction, connecting Montgomery and Prince George's Counties near the Beltway, with 21 stations. The Purple Line will connect directly with four Metro stations, MARC trains and Amtrak.[139]

Air

The Montgomery County Airpark (FAA GAI, ICAO KGAI), a general aviation facility in Gaithersburg, is the major airport in the county. Davis Airport (FAA Identifier W50), a privately owned airstrip, is located in Laytonsville on Hawkins Creamery Road.[140] Commercial air service is provided at the nearby Ronald Reagan Washington National, Washington Dulles International, and BWI Airports.

Education

Educative system is conformed by Montgomery County Public Schools, Montgomery College and other institutions in the area.

Montgomery County Public Schools

Elementary and secondary public schools are operated by the Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS). The county public school system is the largest school district in Maryland, serving about 162,000 students with 13,000 teachers and 10,000 support staff. The public school system operating budget for Fiscal Year 2019 is $2.6 billion.[141]

MCPS operates under the jurisdiction of an elected Board of Education. Its current members are:[142]

| Name | District | Term Ends |

|---|---|---|

| Patricia O'Neill | District 3 , Vice President | 2022 |

| Brenda Wolff | District 5 | 2022 |

| Jeanette Dixon | At Large | 2020 |

| Karla Silvestre | At Large | 2022 |

| Judith Docca | District 1 | 2022 |

| Rebecca Smondrowski | District 2 | 2020 |

| Shebra Evans | District 4, President | 2020 |

| Nate Tinbite | At Large, Student Member | 2020 |

| Dr. Jack Smith | Superintendent | 2020 |

MCPS conducted its first 'data deletion week' in 2019, purging its databases of unnecessary student information.[143] Parents said they hoped to shield children from being held accountable in adulthood for youthful mistakes, as well as to guard them from exploitation by what one parent termed “the student data surveillance industrial complex”.The district also requires tech companies to annually delete data they collect on schoolchildren. In December 2019 it said GoGuardian had sent formal certification that it had deleted its data, but the district was still waiting for confirmation from Google.[144]

Montgomery College

The county is also served by Montgomery College, a public, open access community college that has a budget of $315 million USD for FY2020. The county has no public university of its own, but the state university system does operate a facility called Universities at Shady Grove in Rockville that provides access to baccalaureate and Master's level programs from several of the state's public universities.

Montgomery County Public Libraries

Montgomery County Public Libraries (MCPL) is the public library system for residents of Montgomery County, Maryland. The system includes 23 individual libraries. It has a budget $38 million for 2015.

The "Smondrowski Amendment"

On November 11, 2014, the Board approved an amendment introduced by Rebecca Smondrowksi to modify the school calendar to delete all references to religious holidays such as Christmas, Easter, Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. The amendment was in response to requests by an interfaith organization called Equality for Eid which asked that the listing for the Islamic holiday, Eid Al-Adha be listed alongside Yom Kippur which occurred on the same day.

The Smondrowski amendment received both national[145] and international[146] attention. Criticism of the Smondrowski amendment came from a variety of sources including the Montgomery County Executive, Isiah Leggett, and congressman John Delaney.[147]

Culture

Religion

Montgomery County is religiously diverse. Of Montgomery County's population, according to the Associations of Religion Data, 13% is Catholic, 5% is Baptist, 4% is Evangelical Protestant, 3% is Jewish, 3% is Methodist/Pietist, 2% is Adventist, 2% is Presbyterian, 1% is Episcopalian/Anglican, 1% is Mormon, 1% is Muslim, 1% is Lutheran, 1% is Eastern Orthodox, 1% is Pentecostal, 1% is Buddhist, and 1% is Hindu.[148][N 2]

The Seventh-day Adventist Church maintains its General Conference headquarters in Silver Spring, Maryland.[149]

Sports

The county is home to the National Women's Soccer League team Washington Spirit, a professional soccer team that played its home games at the Maryland SoccerPlex sports complex in Boyds.[150]. In 2021, the Spirit will play its seven home games at Audi Field, in Washington, DC and five home games at Segra Field in Leesburg, VA. [151] Starting in 2022, the team wil work to maximize the number of games played at Audi Field.

Bethesda's Congressional Country Club has hosted four Major Championships, including three playings of the U.S. Open, most recently in 2011 which was won by Rory McIlroy. The Club also hosts the Quicken Loans National, an annual event on the PGA Tour which benefits the Tiger Woods Foundation. Previously, neighboring TPC at Avenel hosted the Booz Allen Classic.

The award-winning Members Club at Four Streams is located on a former farm in Beallsville, Maryland.

The Bethesda Big Train, Rockville Express, and Silver Spring-Takoma Thunderbolts all play college level wooden bat baseball in the Cal Ripken Collegiate Baseball League.

Montgomery County is home of the Montgomery County Swim League, a youth (ages 4–18) competitive swimming league composed of ninety teams based at community pools throughout the county.

The King Farm Park in Rockville, open and accessible 24/7 without cost, provides a first-class 16-station Bankshot Playcourt, the Home Court for the Rockville based Bankshot Sports Organization advocating "Total-mix diversity based on Universal Design." Hundreds of communities provide Bankshot Playcourts mainstreaming differently-able participants in community sports. Bankshot basketball Playcourts are also at Montrose park, the JCC among other locations.

Montgomery County Agricultural Fair

Since 1949 the Montgomery County Agricultural Fair, the largest in the state, showcases farm life in the county. The week long event offers family events, carnival rides, live animals, entertainment and food. Visitors can also view entries of canned and baked goods, clothing, quilts and produce from local county farmers.[152]

Communities

Gaithersburg

Gaithersburg Rockville

Rockville.jpg) Takoma Park

Takoma Park

Cities

- Gaithersburg

- Rockville (county seat)

- Takoma Park

Towns

Villages

Special Tax Districts

Occupying a middle ground between incorporated and unincorporated areas are Special Tax Districts, quasi-municipal unincorporated areas created by legislation passed by either the Maryland General Assembly or the county.[153] The Special Tax Districts generally have limited purposes, such as providing some municipal services or improvements to drainage or street lighting.[153] Special Tax Districts lack home rule authority and must petition their cognizant governmental entity for changes affecting the authority of the district. The four incorporated villages of Montgomery County and the town of Chevy Chase View were originally established as Special Tax Districts. Four Special Tax Districts remain in the county:

Census-designated places

Bethesda

Bethesda- Germantown

Silver Spring

Silver Spring

Unincorporated areas are also considered as towns by many people and listed in many collections of towns, but they lack local government. Various organizations, such as the United States Census Bureau, the United States Postal Service, and local chambers of commerce, define the communities they wish to recognize differently, and since they are not incorporated, their boundaries have no official status outside the organizations in question. The Census Bureau recognizes the following census-designated places in the county:

- Ashton-Sandy Spring

- Aspen Hill

- Bethesda

- Brookmont

- Burtonsville

- Cabin John

- Calverton (partly in Prince George's County)

- Clarksburg

- Cloverly

- Colesville

- Damascus

- Darnestown

- Fairland

- Forest Glen

- Four Corners

- Germantown

- Glenmont

- Hillandale (partly in Prince George's County)

- Kemp Mill

- Layhill

- Leisure World

- Montgomery Village

- North Bethesda

- North Potomac

- Olney

- Potomac

- Redland

- Silver Spring

- South Kensington

- Travilah

- White Oak

- Wheaton

Unincorporated communities

Notes

- Although Rockville is the most populous incorporated city in Montgomery County, Germantown, an unincorporated census-designated place, is the most populous locale in the county.

- These figures count adherents, meaning all full members, their children, and others who regularly attend services. In all of Montgomery County, 40% of the population is adherent to any particular religion.

References

- "Chapter 66. 'Village of Friendship Heights.'". Montgomery County Charter. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

County of Montgomery

- "Montgomery County". GeoNames.org. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Montgomery County Centennial: An Old-Fashioned Maryland Reunion". The Baltimore Sun. September 7, 1876. p. 1. ProQuest 534282014.

- Maryland. Convention (1836). Proceedings of the Conventions of the providence of Maryland, held at the city of Annapolis, in 1774, 1775, & 1776. Baltimore, Md.; Annapolis, Md.: Baltimore, James Lucas & E. K. Deaver; Annapolis, Jonas Green. p. 242. hdl:loc.gdc/scd0001.00117695347. LCCN 10012042. OCLC 3425542. OL 7018977M.

Resolved, That after the first day of October next, such part of the said county of Frederick as is contained within the bounds and limits following, to wit : beginning at the east side of the mouth of Rock creek on Potowmac river, and running with the said river to the mouth of Monocacy, then with a straight line to Par's spring, from thence with the lines of the county to the beginning, shall be and is hereby erected into a new county by the name of Montgomery county.

- "Maryland Senators, Representatives, and Congressional District Maps". GovTrack.us. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- "QuickFacts Montgomery County, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "Maryland by Place – GCT-PH1-R. Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density (geographies ranked by total population): 2000". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- Morello, Carol; Mellnick, Ted (September 19, 2012). "Seven of nation's 10 most affluent counties are in Washington region". Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- Bureau, U. S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau.

- "Complete List: America's Richest Counties" Archived April 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, February 2, 2008

- "Montgomery County QuickFacts" Archived June 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, September 9, 2009

- Archived February 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, February 26, 2015

- Archived February 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Montgomery County Chamber of Commerce, February 26, 2015

- Tom (November 7, 2012). "Why Is It Named Montgomery County?". Ghosts of DC. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Rapid Transit - Montgomery County, MD. "Get On Board BRT - Vote Now!" – via YouTube.

- Council, Montgomery (November 15, 2016). "@CoUnTy_ExEc talks about his mission to make #MoCo one of the most welcoming places on earth. #CommunityMatterspic.twitter.com/EJuLFi2NAz". Archived from the original on June 12, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- Clan Montgomery Society (June 14, 2008). "Montgomery Motto". Clan Montgomery Symbols. Clan Montgomery Society. Archived from the original on September 5, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

"Garde" (pronounced gard-uh) or "Gardez" (pronounced garday) means "watch", in the sense of "look out" or "on guard". "Bien" (pronounced bee-ann) means "good" to give the overall meaning of "Watch Well".

- "Places From the Past". Montgomery County Historic Sites. 8787 Georgia Avenue, Silver Spring, Maryland, 20910: Montgomery County Planning Department. January 26, 2012. Archived from the original on April 30, 2012. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

Gardez Bien, adopted in 1976 as the county motto, means to guard well or take good care

CS1 maint: location (link) - House of Names (2014). "Montgomery Family Crest and Name History". House of Names. Swyrich Corporation. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- Offutt, pages 11–13

- Offutt, page 9

- Offutt, pages 18–19

- Offutt, pages 19–21

- Offutt, page 23

- MacMaster, Richard K.; Hiebert, Ray Eldon (1976). A Grateful Remembrance: The Story of Montgomery County, Maryland 1776–1976. Rockville, MD: Montgomery County Government and Montgomery County Historical Society. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-9643819-8-8.

- Offutt, page 28

- Farquhar, Roger Brooke (1952). Historic Montgomery County, Old Homes and History. Baltimore, Maryland: Monumental Printing Company. p. 20.

- McMaster and Hiebert, p 41

- Offutt, pages 29–30

- Boyd, T.H.S. (1879). The History of Montgomery County, Maryland from Its Earliest Settlement in 1650 to 1879. Clarksburg, Maryland: Regional Publishing Company. p. 52–54.

- Sween, Jane C.; Offutt, William. Montgomery County: Centuries of Change. American Historical Press, 1999. ISBN 1-892724-05-7.

- Offutt, page 32

- MacMaster and Hiebert, p 101

- MacMaster and Hiebert, p 152

- MacMaster and Hiebert, p 113-116

- McMaster and Hiebert, p 48

- MacMaster and Hiebert, p 154

- "Colored School in Rockville Closed". Washington Evening Star. June 25, 1866. p. 2.

- "The colored public school in Rockville, Md. has over a hundred pupils, some of whom live five miles from town, but walk to and from school regularly". Washington Evening Star. May 19, 1877. p. 5.

- Charles T. Jacobs (November 16, 2009). "Civil War Guide to Montgomery County, Maryland". The Smithsonian Associates Civil War E-Mail Newsletter. civilwarstudies.org. Archived from the original on December 1, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- Office of Metropolitan Railroad Company (January 16, 1855). "Notice to Contractors" (classified advertisement). Washington Evening Star. p. 4.

- MacMaster and Hiebert, p 209-10

- "Lynched a Suspected Negro; Mob Had No Proof on". The New York Times. July 5, 1896. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- "A Brutal Negro Lynched; Taken From a Maryland Jail and Hanged". The New York Times. July 28, 1880. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- "Rockville Civil War Monument - Rockville, MD - American Civil War Monuments and Memorials on". Waymarking.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- "Veterans Home Page". Maryland Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- "Civil War Sesquicentennial Commemoration, 1861-1865, Montogmery County, Maryland". Heritage Montgomery. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- Loewen, James W. (July 1, 2015). "Why do people believe myths about the Confederacy? Because our textbooks and monuments are wrong. False history marginalizes African Americans and makes us all dumber". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Graham Holdings Company. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

Confederate cavalry leader Jubal Early demanded and got $300,000 from them lest he burn their town, a sum equal to at least $5,000,000 today.

- "Riding Off Into the Sunset". The Washington Sentinel. February 2016. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "County police department celebrates 75th anniversary". The Gazette. 9030 Comprint Court, Gaithersburg, Maryland, 20877: Post-Newsweek Media, Inc. July 2, 1997. Archived from the original on January 15, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2014.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Montgomery County, Maryland – Government, Executive Branch, Public Safety: Department of Police". Maryland State Archives. State of Maryland. Archived from the original on September 5, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- Kelly, John (September 13, 2014). "Local F. Scott Fitzgerald's long journey to a Rockville, Md., cemetery". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Venemann, Chester R. (August 31, 1942). "Many Confused By Charter Fight: Montgomery Plan Is Explained as Merely Opening Chance of Reform to Voters". The Washington Post. p. B11.

- "Proclamation: Proposed Amendments to the Constitution of Maryland". The Baltimore Sun. August 3, 1915. p. 11.

- "Arlington Manager Plan Wins Handily: Voters Back Selection of Five Commissioners from County at Large". The Washington Post. November 5, 1930. p. 2.

- Hiebert, Ray Eldon; MacMaster, Richard K. A Grateful Remembrance: The Story of Montgomery County. Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Government and the Montgomery County Historical Society. 1976. pp. 313–315.

- "Brookings Institution to Make Montgomery County Survey: Commissioners Limit Cost to $5,000; Report to Include Recommended Changes; Board is Unanimous in Acceptance". The Washington Post. November 30, 1938. p. 16.

- Secrest, James D. (March 16, 1941). "Overhaul Montgomery Setup, Brookings Report Recommends: Montgomery Setup, Brookings Report Recommends". The Washington Post. p. 1.

- "Brookings Montgomery Survey Praised". The Washington Post. March 17, 1941. p. 8.

- "Officials Call Brookings Plan Radical: Would Scrap Time-Honored System, Assert Montgomery Heads". The Washington Post. August 20, 1941. p. 13.

- "Citizens Seek County Charter In Montgomery". The Washington Post. July 2, 1942. p. 30.

- "More Home Rule Called Charter Aim". The Washington Post. August 15, 1942. p. 12. ProQuest 151576558.

- Venemann, Chester R. (September 4, 1942). "Montgomery Politicians Mum On Charter Vote Predictions". The Washington Post. p. B8. ProQuest 151465247.

- "Democrats Give Statement On Charter". The Washington Post. September 6, 1942. p. X7. ProQuest 151471916.

- "Democrats Spurn Truce in Charter Fight". The Washington Post. September 13, 1942. p. SP8. ProQuest 151517856.

- "Montgomery Independents Back Charter". The Washington Post. September 5, 1942. p. 16. ProQuest 151549333.

- "Montgomery Now Faces Job Of Drafting County Charter". The Washington Post. November 5, 1942. p. 15. ProQuest 151518727.

- "Board of 9 Men Would Rule Montgomery County Under Terms of New Charter". The Washington Post. April 12, 1943. p. 8. ProQuest 151647497.

- "Anticharter Unit Forms in Montgomery". The Washington Post. August 25, 1944. p. 9. ProQuest 151699677.

- "Charter Committee Opens Headquarters in Montgomery". The Washington Post. May 16, 1944. p. 4. ProQuest 151720430.

- "Montgomery Charter". The Washington Post. April 17, 1943. p. 10. ProQuest 151651081.

- "Montgomery Women Voters Back Charter". The Washington Post. March 25, 1944. p. 3. ProQuest 151732288.

- "Near-Record Vote Crowds Md. Polls". The Washington Post. Associated Press. November 8, 1944. p. 5. ProQuest 151729229.

- "Charter Plan In Montgomery Is Defeated". The Washington Post. November 9, 1944. p. 7. ProQuest 151729229.

- "Mr. Lee's Sudden Switch To The Support Of Home Rule". The Baltimore Sun. February 14, 1945. p. 12. ProQuest 539640017.

- "Will Montgomery County Have Better Government Now?". The Baltimore Sun. July 28, 1945. p. 6. ProQuest 537422500.

- "Montgomery Votes Heavily For Charter: Montgomery Votes Charter". The Washington Post. November 3, 1948. p. 1. ProQuest 152056350.

- Feinberg, Lawrence (April 24, 1968). "Montgomery Council Expansion Proposed". The Washington Post. p. B1. ProQuest 143395883.

- Rovner, Sandy (August 7, 1967). "Montgomery Plan Devised: It Adds Full-Time, Elected President Of Council". The Baltimore Sun. p. A7. ProQuest 534370489.

- "A New Government In Montgomery County". The Baltimore Sun. January 19, 1949. p. 10. ProQuest 541928116.

- Farquhar, Roger B. (November 4, 1948). "Charter Council Plan Set in Motion". The Washington Post. p. 4. ProQuest 152065714.

- Dessoff, Alan L. (June 12, 1962). "Citizens Group Urges Big Changes in County". The Washington Post. p. B9. ProQuest 141595914.

- Dessoff, Alan L. (December 10, 1962). "Citizens Propose Major Changes In Montgomery Government Plan". The Washington Post. p. A1. ProQuest 141644784.

- Yenckel, James T. (July 13, 1966). "Voters Will Decide On New Executive For Montgomery". The Washington Post. p. C2. ProQuest 142810914.

- Gresham, Katharine (November 3, 1966). "Republicans Push County Executive For Montgomery". The Washington Post. p. G6. ProQuest 142725620.

- Douglas, Walter B. (October 16, 1966). "Montgomery to Vote On Elected Executive: Party Stands Other Questions". The Washington Post. p. B2. ProQuest 142817467.

- "Referendum Prepared on County Shift". The Washington Post. July 20, 1966. p. C4. ProQuest 142824925.

- "Montgomery County Unofficial Vote Tally". The Washington Post. November 10, 1966. p. A9. ProQuest 142650577.

- Rovner, Sandy (February 8, 1967). "Montgomery Head Urged: Council Moves To Provide For County Executive". The Baltimore Sun. p. A9. ProQuest 539432226.

- Feinberg, Lawrence (October 20, 1968). "Montgomery Charter Draws Little Fire: Center of Argument". The Washington Post. p. D2. ProQuest 143430376.

- Rovner, Sandy (November 6, 1968). "Charter Backed in Montgomery: First County Executive To Be Elected In 2 Years". The Baltimore Sun. p. C11. ProQuest 539353597.

- "Greenhalgh Concedes Race: For Montgomery Executive". The Washington Post. November 9, 1970. p. C1. ProQuest 147858581.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland: Our History and Government" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- Montgomery, David (November 8, 1995). "In a Montgomery State of Mind, Takoma Park Votes to Unify". Washington Post.

- "Substantial Changes to Counties and County Equivalent Entities: 1970-Present". Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 15, 2001. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- Montgomery, David (July 12, 1995). "P.G. Council to Let Voters Make Annexation Decision: Takoma Park Wants to Absorb 3 Neighborhoods". The Washington Post. p. B8. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- "Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV". U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Intellicast - Rockville Historic Weather Averages in Maryland (20857)". Accuweather. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- "Intellicast - Silver Spring Historic Weather Averages in Maryland (20901)". Accuweather. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- Samenow, Jason (March 18, 2014). "Astonishing snow totals this winter in upper Montgomery County: nearly 70 inches". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Intellicast - Damascus Historic Weather Averages in Maryland (20872)". Accuweather. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- Wheatley, Katie; Livingston, Ian (May 9, 2014). "How much snow fell in your backyard? Mapping the 2013-2014 winter snow totals in the Mid-Atlantic". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 10, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- "Population of Montgomery County, MD - Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts - CensusViewer". censusviewer.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "2010 Census Summary File One (SF1) - Maryland Population Characteristics, Montgomery County Archived February 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". United States Census Bureau via Maryland State Data Center.

- "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland". State & County Quickfacts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- "African Community Archived December 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". Office of Community Partnerships. Montgomery County Government. 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "QuickFacts: Montgomery County, Maryland Archived February 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland Archived December 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine". Quick Facts. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Montgomery County, Maryland". www.census.gov. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland: Religion Archived October 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine". Sperling's BestPlaces. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- "United States Jewish Population, 2018" (PDF). Berman Jewish DataBank. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "D.C. area's Jewish population is booming: Now the third largest in the nation, report says". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ending June 30, 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2012.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ending June 30, 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2012.