Zoning in the United States

Zoning in the United States includes various land use laws falling under the police power rights of state governments and local governments to exercise authority over privately owned real property. The earliest zoning laws originated with the Los Angeles zoning ordinances of 1908 and the New York City Zoning resolution of 1916. Starting in the early 1920s, the United States Commerce Department drafted model zoning and planning ordinances in the 1920s to facilitate states in drafting enabling laws. Also in the early 1920s, a lawsuit challenged a local zoning ordinance in a suburb of Cleveland, which was eventually reviewed by the United States Supreme Court (Euclid v. Ambler Realty).

According to the New York Times, "single-family zoning is practically gospel in America," as a vast number of cities zone land extensively for detached single-family homes.[1] The housing shortage in many metropolitan areas, coupled with racial residential segregation, has led to increased public focus and political debates on zoning laws.[2][3] Strict zoning laws contribute to racial housing segregation in the United States,[4][5] and zoning laws that prioritize single-family housing have raised concerns regarding housing availability, housing affordability and the environment.[1][6]

Origins and history

Zoning, narrowly construed, refers to the designation of discrete land uses to well-defined areas of the city. More broadly construed, zoning refers to a wide range of local regulations enabled by police powers delegated from the states. In the beginning, zoning ordinances in the United States were more narrow in scope, and later ordinances were more comprehensive.

1908–1930

1908 Los Angeles zoning ordinances

Los Angeles City Council passed the first municipal zoning ordinance in the United States on September 24, 1908. Though the ordinance did not assign all parts of the city to a zoning map, as with later American ordinances, it did establish both residential and industrial districts. Existing nuisance laws had already prohibited some industrial land uses in Los Angeles. Dangerous businesses (such as warehousing explosives) were illegal before 1908, as were odorous land uses, such as slaughterhouses and tanneries. The ordinance created three large residential districts with identical laws, and they all prohibited business such as laundries, lumber yards, and in general, any industry using equipment driven by motors. The law could cause businesses to relocate retroactively, and did not require compensation. The prohibition against laundries had a racial component since many were owned by Chinese residents and citizens. The California Supreme Court had already upheld such rules in Yick Wo (1886). Many later California court cases supported the 1908 ordinance, even in one case of ex post facto relocation of an existing brickyard.[7]

The same 1908 ordinance established eight industrial districts. These were drawn mainly in areas which had already hosted significant industrial development, within corridors along the freight railroads and the Los Angeles River. However, between 1909 and 1915, Los Angeles City Council responded to some requests by business interests to create exceptions to industrial bans within the three 1908 Residential Districts. They did this through the legal device of districts within districts. While some might have been benign, such as motion picture districts, some others were polluting, such as poultry slaughterhouse districts. Despite the expanding list of exceptions, new ordinances in other cities (i.e., 1914 Oakland ordinance) followed the 1908 Los Angeles model through about 1917.[7] There existed 22 cities with zoning ordinances by 1913.[8]

Race-based zoning ordinances, 1910–1917

Many American cities passed residential segregation laws based on race between 1910 and 1917. Baltimore City Council passed such a law in December 1910.[9][10] Unlike the Los Angeles Residential District which created well-defined areas for residential land use, the Baltimore scheme was implemented on a block-by-block basis. Druid Hill had already existed as a de facto all-black neighborhood, but some whites in nearby neighborhoods protested for formal segregation. Just a few months later, Richmond, Virginia passed its race-based zoning law, though it was struck down by the Virginia Supreme Court. Over the next few years, several southern cities established race-based residential zoning ordinances, including four other cities in Virginia, one in North Carolina, and another in South Carolina. Atlanta passed a law similar to 1910 Baltimore ordinance. Before 1918, race-based zoning ordinances were adopted in New Orleans, Louisville, St. Louis, and Oklahoma City.[10]

In the end, the United States Supreme Court struck down the Louisville ordinance, ruling in Buchanan v. Warley that race-based zoning was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment;[9][10] more specifically, the Court held that the law violated the "right to contract" and the right to alienate property.[11] Despite the Buchanan ruling, the city of Atlanta devised a new race-based zoning ordinance, arguing that the Supreme Court had merely applied to specific defects of the Louisville ordinance. Even after the Georgia Supreme Court struck down the Atlanta ordinance, the city continued to use their racially based residential zoning maps. Other municipalities tested the limits of Buchanan; Florida, Apopka and West Palm Beach drafted race-based residential zoning ordinances. Birmingham, Indianapolis, and New Orleans all passed race-based zoning laws, while Atlanta, Austin, Kansas City, Missouri, and Norfolk considered race in their "spot zoning" decisions. In some cases, these practices continued for decades after Buchanan.[11]

1916 New York Zoning Resolution

In 1916, New York City adopted the first zoning regulations to apply citywide as a reaction to construction of the Equitable Building (which still stands at 120 Broadway). The building towered over the neighboring residences, completely covering all available land area within the property boundary, blocking windows of neighboring buildings and diminishing the availability of sunshine for the people in the affected area.[12]

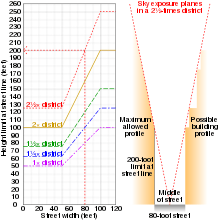

Bassett's zoning map established height restrictions for the entire city, expressed as ratios between maximum building height and the width of adjacent streets. Residential zones were the most restrictive, limiting building height to no higher than the width of adjoining streets. The law also regulated land use, preventing factories and warehousing from encroaching on retail districts.[13]

These laws, written by a commission headed by Edward Bassett and signed by Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, became the blueprint for zoning in the rest of the country, partly because Bassett headed the group of planning lawyers who wrote The Standard State Zoning Enabling Act that was issued by the U.S. Department of Commerce in 1924 and accepted almost without change by most states. The effect of these zoning regulations on the shape of skyscrapers was illustrated famously by architect and illustrator Hugh Ferriss.[14]

Standard State Zoning Enabling Act

The State Standard Zoning Enabling Act (SZEA) is a federal planning document drafted and published through the United States Commerce Department in 1924, which gave states a model under which they could enact their own zoning enabling laws. The genesis for this act is the initiative of Herbert Hoover while he was Secretary of Commerce. Deriving from a general policy to increase home ownership in the United States, Secretary Hoover established the Advisory Committee on Zoning, which was assigned the task of drafting model zoning statutes. This committee was later known as the Advisory Committee on City Planning and Zoning. Among the members of this committee were Edward Bassett, Alfred Bettman, Morris Knowles, Nelson Lewis, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and Lawrence Veiller.[15]

The Advisory Committee on Zoning appointed a subcommittee under the title of "Laws and Ordinances." This committee—which included Bassett, Knowles, Lewis, and Veiller—composed a series of drafts for SZEA, with one dated as early as December 15, 1921. A second draft came forth from the subcommittee in January 1922. Several drafts culminated in the first published document in 1924, which was revised and republished in 1926.[15]

New York City went on to develop more complex zoning regulations encompassing floor-area ratio regulations, air rights, and other regulations.

Euclid v. Ambler Realty

The constitutionality of zoning ordinances was upheld in 1926. The zoning ordinance of Euclid, Ohio was challenged in court by a local land owner on the basis that restricting use of property violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Ambler Realty Company filed suit on November 13, 1922 against the Village of Euclid, Ohio, alleging that the local zoning ordinances effectively diminished its property values. The village had zoned an area of land held by Ambler Realty as a residential neighborhood. Ambler argued that it would lose money because if the land could be leased to industrial users it would have netted a great deal more money than as a residential area. Ambler Realty claimed these breaches implied an unconstitutional taking of property and denied equal protection under the law.[16]

Although initially ruled unconstitutional by lower courts, ultimately the zoning ordinance was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Village of Euclid, Ohio v. Ambler Realty Co..

In doing so, the court accepted the arguments of zoning defenders that it met two essential needs. First, zoning extended and improved on nuisance law in that it provided advance notice that certain types of uses were incompatible with other uses in a particular district. The second argument was that zoning was a necessary municipal-planning instrument.

The Euclid case was a facial challenge, meaning that the entire scheme of regulation was argued to be unconstitutional under any set of circumstances. The United States Supreme Court justified the ordinance saying that a community may enact reasonable laws to keep the pig out of the parlor, even if pigs may not be prohibited from the entire community.

Since the Euclid case, there have been no more facial challenges to the general scheme. By the late 1920s most of the nation had developed a set of zoning regulations.

Houston, 1924–1929

Houston remains an exception within the United States because it never adopted a zoning ordinance. However, strong support existed for zoning in Houston among elements within municipal government and among the city's elites during the 1920s. In 1924, Mayor Oscar Holcombe, appointed the first funded City Planning Commission. City Council voted in favor of hiring S. Herbert Hare of Hare and Hare as a planning consultant. Following the passage of a state zoning enabling statute in 1927, Holcombe appointed Will Hogg to chair a new City Planning Commission.[8] Will Hogg was a co-founder of the River Oaks development, the son of a former Texas Governor and an heir to family oil wealth.[17] By 1929, both Hare and Hogg abandoned efforts to push the zoning ordinance to a referendum. In their estimation, there was not enough support for it. Hogg resigned as chair of the City Planning Commission that year.[8]

Among large populated cities in the United States, Houston is unique as the largest city in the country with no zoning ordinances. Houston voters have rejected efforts to implement zoning in 1948, 1962, and 1993. It is commonly believed that "Houston is Houston" because of the lack of zoning laws.[18] Houston is similar, however, to other large cities throughout the Sun Belt, who all experienced the bulk of their population growth during the Age of the Automobile. The largest of these cities, such as Los Angeles, Atlanta, Miami, Tampa, Dallas, Phoenix, and Kansas City, have all expanded their metropolitan footprints along with Houston while having land use zoning.[19][20][21]

While Houston has no official zoning ordinances, many private properties have legal covenants or "deed restrictions" that limit the future uses of land, with effects similar to those of zoning systems.[20][22]

Also, the city has enacted development regulations that specify how lots are subdivided, standard setbacks, and parking requirements.[23] The regulations have contributed to the city's automobile-dependent sprawl, by requiring the existence of large minimum residential lot sizes and large commercial parking lots.[24]

Without land use-based zoning, many neighborhoods in the inner-ring outskirts, such as Montrose, feature small businesses such as bars, restaurants, mechanics, and hardware stores that are mixed in among residential streets.

Scope

Theoretically, the primary purpose of zoning is to segregate uses that are thought to be incompatible. In practice, however, zoning is used as a permitting system to prevent new development from harming existing residents or businesses. Zoning is commonly exercised by local governments such as counties or municipalities, although the state determines the nature of the zoning scheme with a zoning enabling law. Federal lands are not subject to state planning controls.

Zoning may include regulation of the kinds of activities that will be acceptable on particular lots (such as open space, residential, agricultural, commercial, or industrial), the densities at which those activities may be performed (from low-density housing such as single family homes to high-density such as high-rise apartment buildings), the height of buildings, the amount of space structures may occupy, the location of a building on the lot (setbacks), the proportions of the types of space on a lot (for example, how much landscaped space and how much paved space), and how much parking must be provided. Some commercial zones specify what types of products may be sold by particular stores.[25] The details of how individual planning systems incorporate zoning into their regulatory regimes varies although the intention is always similar.

Most zoning systems have a procedure for granting variances (exceptions to the zoning rules), usually because of some perceived hardship due to the particular nature of the property in question. If the variance is not warranted, then it may cause an allegation of spot zoning to arise. Most state zoning-enabling laws prohibit local zoning authorities from engaging in any spot zoning because it would undermine the purpose of a zoning scheme.[26]

Zoning codes vary by jurisdiction. As one example, residential zones might be coded as R1 for single-family homes, R2 for two-family homes, and R3 for multiple-family homes. As another example, R60 might represent a minimum lot of 60,000 sq. ft. (1.4 acre or about 0.5 hectares) per single family home, while R30 might require lots of only half that size.

Mature zoning practices

Legal challenges

There are several limitations to the ability of local governments in asserting police powers to control land use. First, constitutional constraints include freedom of speech (First Amendment), unjust takings of property (Fifth Amendment), and equal protection (Fourteenth Amendment). There are also federal statutes that sometimes constrain local zoning. These include the Federal Housing Amendments Act of 1988, the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000.[27]

Freedom of Speech

Local governments regulate signage on private property through zoning ordinances. Sometimes courts invalidate laws which regulate the content of speech rather than the manners and modes of speech. One court invalidated a local ordinance that prohibited "for sale" and "sold" signs on private property. Another court struck down a law which prohibited signs for adult cabarets.[27]

Takings after 1987

Beginning in 1987, several United States Supreme Court cases ruled against land use regulations as being a taking requiring just compensation pursuant to the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. First English Evangelical Lutheran Church v. Los Angeles County ruled that even a temporary taking may require compensation. Nollan v. California Coastal Commission ruled that construction permit conditions that fail to substantially advance the agency's authorized purposes, require compensation. Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council ruled that numerous environmental concerns were not sufficient to deny all development without compensation. Dolan v. City of Tigard ruled that conditions of a permit must be roughly proportional to the impacts of the proposed new development. Palazzolo v. Rhode Island ruled property rights are not diminished by unconstitutional laws that exist without challenge at the time the complaining property owner acquired title.

The landowner victories have been limited mostly to the U.S. Supreme Court, however, despite that Court's purported overriding authority. Each decision in favor of the landowner is based on the facts of the particular case, so that regulatory takings rulings in favor of landowners are little more than a landowners' mirage. Even the trend of the U.S. Supreme Court with the 2002 ruling in Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, who had previously ruled with a 5-4 majority in favor of the landowner, switched sides to favor the government that had delayed development for more than 20 years because of the government's own indecision about alleged concerns about the water quality of Lake Tahoe.

Equal protection

Specific zoning laws have been overturned in some other U.S. cases where the laws were not applied evenly (violating equal protection) or were considered to violate free speech. In the Atlanta suburb of Roswell, Georgia, an ordinance banning billboards was overturned in court on such grounds. It has been deemed that a municipality's sign ordinance must be content neutral with regard to the regulation of signs. The city of Roswell, Georgia now has instituted a sign ordinance that regulates signs, based strictly on dimensional and aesthetic codes rather than an interpretation of the sign content (i.e. use of colors, lettering, etc.).

Religious exercise

On other occasions, religious institutions sought to circumvent zoning laws, citing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA). The Supreme Court eventually overturned RFRA in just such a case, City of Boerne v. Flores 521 U.S. 507 (1997). Congress enacted the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) in 2000, however, in an effort to correct the constitutionally objectionable problems of the RFRA.[28]

In the 2005 case of Cutter v. Wilkinson, the United States Supreme Court held RLUIPA to be constitutional as applied to institutionalized persons, but has not yet decided RLUIPA's constitutionality as it relates to religious land uses.

Types

Zoning codes have evolved over the years as urban planning theory has changed, legal constraints have fluctuated, and political priorities have shifted.[29] The various approaches to zoning may be divided into four broad categories: Euclidean, Performance, Incentive, and Form-based.

Euclidean

Conventional

Named for the type of zoning code adopted in the town of Euclid, Ohio, Euclidean zoning codes are by far the most prevalent in the United States, being used extensively in small towns and large cities alike.

Standard Euclidean

Also known as "Building Block" zoning, Euclidean zoning is characterized by the segregation of land uses into specified geographic districts and dimensional standards stipulating limitations on the magnitude of development activity that is allowed to take place on lots within each type of district. Typical types of land-use districts in Euclidean zoning are: residential (single-family), residential (multi-family), commercial, and industrial. Uses within each district are usually heavily prescribed to exclude other types of uses (residential districts typically disallow commercial or industrial uses). Some "accessory" or "conditional" uses may be allowed in order to accommodate the needs of the primary uses. Dimensional standards apply to any structures built on lots within each zoning district, and typically, take the form of setbacks, height limits, minimum lot sizes, lot coverage limits, and other limitations on the building envelope.

Euclidean zoning is preferred by many municipalities, due to its relative effectiveness, ease of implementation (one set of explicit, prescriptive rules), long-established legal precedent, and familiarity to planners and design professionals. Euclidean zoning has been criticized, however, for its lack of flexibility. Separation of uses contributes to urban sprawl, loss of open space, heavy infrastructure costs, and automobile dependency.

Euclidean II

Euclidean II Zoning uses traditional Euclidean zoning classifications (industrial, commercial, multi-family, residential, etc.), but places them in a hierarchical order "nesting" one zoning class within another similar to the concept of Planned Unit Developments (PUD) mixed uses, but now for all zoning districts.

For example, multi-family is not only permitted in "higher order" multi-family zoning districts, but also permitted in high order commercial and industrial zoning districts as well. Protection of land values is maintained by stratifying the zoning districts into levels according to their location in the urban society (neighborhood, community, municipality, and region). Euclidean II zoning also incorporates transportation and utilities as new zoning districts in its matrix dividing zoning into three categories: public, semi-public and private. In addition, all Euclidean II Zoning permitted activities and definitions are tied directly to the state's building code, Municode, and the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) assuring statewide uniformity. Euclidean II zoning fosters the concepts of mixed use, new urbanism and "highest and best use" and, simplifies all zoning classifications into a single and uniform set of activities. It is relatively easy to make a transition from most existing zoning classification systems to the Euclidean II Zoning system.

Smart zoning

Smart zoning (or smart coding) is an alternative to Euclidean zoning. There are a number of different techniques to accomplish smart zoning. Floating zones, cluster zoning, and planned unit development (PUDs) are possible even as the conventional Euclidean code exists, or the conventional code may be completely replaced by a smart code, as the city of Miami is proposing. The following three techniques may be used to accomplish either conventional separation of uses or more environmentally responsible, traditional neighborhood development, depending on how the codes are written.

For serious reform of Euclidean zoning, traditional neighborhood development ordinances such as form-based codes or the SmartCode are usually necessary.

Floating zones involve an ordinance that describes a zone's characteristics and requirements for its establishment, but its location remains without a designation until the board finds that a situation exists that allows the implementation of that type of zone in a particular area. When the criteria of a floating zone is met the floating zone ceases "to float" and is adopted by a zoning amendment. Some states allow this type of zoning, such as New York and Maryland, while states such as Pennsylvania do not, as an instance of spot zoning.[26] To be upheld, the floating zone the master plan must permit floating zones or at least they should not conflict with the master plan. Further, the criteria and standards provided for them should be adequate and the action taken should not be arbitrary or unreasonable. Generally, the floating zone is more easily adoptable and immune from legal challenges if it does not differ substantially from zoned area in which it is implemented.

Cluster zoning permits residential uses to be clustered more closely together than normally allowed, thereby leaving substantial land area to be devoted to open space.

Planned unit development is cluster zoning, but allows for mixed uses. They include some commercial and light industrial uses in order to blend together a traditional downtown environment, but at a suburban scale. Some have argued, however, that such a planned unit development may be a sham for the purpose of bringing in commercial and industrial uses forbidden by the state's zoning law; some courts have held such a "sham" to be an "arbitrary and capricious abuse" of the police power.

Performance

Also known as "effects-based planning", performance zoning uses performance-based or goal-oriented criteria to establish review parameters for proposed development projects in any area of a municipality. Performance zoning often utilizes a "points-based" system whereby a property developer may apply credits toward meeting established zoning goals through selecting from a 'menu' of compliance options (some examples include: mitigation of environmental impacts, providing public amenities, building affordable housing units, etc.). Additional discretionary criteria may be established also as part of the review process.

The appeal of performance zoning lies in its high level of flexibility, rationality, transparency, and accountability.[30] Performance zoning avoids the arbitrary nature of the Euclidean approach, and better accommodates market principles and private property rights with environmental protection. However, performance zoning can be extremely difficult to implement and can require a high level of discretionary activity on the part of the supervising authority. For this reason, performance zoning has not been adopted widely in the US and is usually limited to specific categories within a broader prescriptive code when found.

New Zealand's planning system is grounded in effects-based performance zoning under the Resource Management Act 1991.

Incentive

First implemented in Chicago and New York City, incentive zoning is intended to provide a reward-based system to encourage development that meets established urban development goals.[31] Typically, a base level of prescriptive limitations on development will be established and an extensive list of incentive criteria will be established for developers to adopt or not, at their discretion. A reward scale connected to the incentive criteria provides an enticement for developers to incorporate the desired development criteria into their projects. Common examples include (floor-area-ratio) bonuses for affordable housing provided on-site and height limit bonuses for the inclusion of public amenities on-site. Incentive zoning has become more common throughout the United States during the last 20 years.

Incentive zoning allows for a high degree of flexibility, but may be complex to administer. The more a proposed development takes advantage of incentive criteria, the more closely it has to be reviewed on a discretionary basis. The initial creation of the incentive structure in order to best serve planning priorities also may be challenging and often, requires extensive ongoing revision to maintain balance between incentive magnitude and value given to developers.

Form-based

Form-based zoning relies on rules applied to development sites according to both prescriptive and potentially discretionary criteria. Typically, these criteria are dependent on lot size, location, proximity, and other various site- and use-specific characteristics. For example, in a largely suburban single family residential area, uses such as offices, retail, or even light industrial could be permitted so long as they conformed (setback, building size, lot coverage, height, and other factors) with other existing development in the area.

Form based codes offer considerably more flexibility in building uses than do Euclidean codes but, as they are comparatively new, may be more challenging to create. Form-based codes have not yet been widely adopted in the United States. When form-based codes do not contain appropriate illustrations and diagrams, they have been criticized as being difficult to interpret.

One example of a recently adopted code with form-based design features is the Land Development Code[32] adopted by Louisville, Kentucky in 2003. This zoning code creates "form districts" for Louisville Metro. Each form district intends to recognize that some areas of the city are more suburban in nature, while others are more urban. Building setbacks, heights, and design features vary according to the form district. As an example, in a "traditional neighborhood" form district, a maximum setback might be 15 feet (4.6 m) from the property line, while in a suburban "neighborhood" there may be no maximum setback.

Dallas, Texas, is currently developing an optional form-based zoning ordinance.[33] Since the concept of form-based codes is relatively new, this type of zoning may be more challenging to enact.

One version of form-based or "form integrated" zoning uses a base district overlay method or "composite" zoning. This method is based on a Euclidean framework and includes three district components - a use component, a site component, and an architectural component.

The use component is similar in nature to the use districts of Euclidean zoning. With an emphasis on form standards, however, use components are typically more inclusive and broader in scope. The site components define a variety of site conditions from low intensity to high intensity such as size and scale of buildings and parking, accessory structures, drive-through commercial lanes, landscaping, outdoor storage and display, vehicle fueling and washing, overhead commercial service doors, etc. The architectural components address architectural elements and materials.

This zoning method is more flexible and contextually adaptable than standard Euclidean zoning while being easier to interpret than other form-based codes.

Amendments to zoning regulations

Amendments to zoning regulations may be subject to judicial review, should such amendments be challenged as ultra vires or unconstitutional.

The standard applied to the amendment to determine whether it may survive judicial scrutiny is the same as the review of a zoning ordinance: whether the restriction is arbitrary or whether it bears a reasonable relationship to the exercise of the police power of the state.

If the residents in the targeted neighborhood complain about the amendment, their argument in court does not allow them any vested right to keep the zoned district the same.[34] However, they do not have to prove the difficult standard that the amendment amounts to a taking.[34] If the gain to the public for the rezoning is small compared to the hardships that would affect the residents, then the amendment may be granted if it provides relief to the residents.[34]

If the local zoning authority passes the zoning amendment, then spot zoning allegations may arise should the rezoning be preferential in nature and not reasonably justified.

Limitations and criticisms

Land-use zoning is a tool in the treatment of certain social ills and part of the larger concept of social engineering. There is criticism of zoning particularly amongst proponents of limited government or Laissez-faire political perspectives. The inherent danger of zoning, as a coercive force against property owners, has been described in detail in Richard Rothstein's book The Color of Law (2017). Government zoning was used significantly as an instrument to advance racism through enforced segregation in the North and South from the early part of the 20th century up until recent decades.[35]

Circumventions

Generally, existing development in a community is not affected by the new zoning laws because it is "grandfathered" or legally non-conforming as a nonconforming use, meaning the prior development is exempt from compliance. Consequently, zoning may only affect new development in a growing community. In addition, if undeveloped land is zoned to allow development, that land becomes relatively expensive, causing developers to seek land that is not zoned for development with the intention to seek rezoning of that land. Communities generally react by not zoning undeveloped land to allow development until a developer requests rezoning and presents a suitable plan. Development under this practice appears to be piecemeal and uncoordinated. Communities try to influence the timing of development by government expenditures for new streets, sewers, and utilities usually desired for modern developments. Contrary to federal recommendations discouraging it, the development of interstate freeways for purposes unrelated to planned community growth, creates an inexorable rush to develop the relatively cheap land near interchanges. Property tax suppression measures such as California Proposition 13 have led many communities desperate to capture sales tax revenue to disregard their comprehensive plans and rezone undeveloped land for retail establishments.

In Colorado, local governments are free to choose not to enforce their own zoning and other land regulation laws. This is called selective enforcement. Steamboat Springs, Colorado is an example of a location with illegal buildings and lax enforcement.[36][37]

Social

In more recent times, zoning has been criticized by urban planners and scholars (most notably Jane Jacobs) as a source of new social ills, including urban sprawl, the separation of homes from employment, and the rise of "car culture." Some communities have begun to encourage development of denser, homogenized, mixed-use neighborhoods that promote walking and cycling to jobs and shopping. Nonetheless, a single-family home and car are major parts of the "American Dream" for nuclear families, and zoning laws often reflect this: in some cities, houses that do not have an attached garage are deemed "blighted" and are subject to redevelopment. Movements that disapprove of zoning, such as New Urbanism and Smart Growth, generally try to reconcile these competing demands. New Urbanists in particular try through creative urban design solutions that hark back to 1920s and 1930s practices. Late in the twentieth century, New Urbanists have also come under attack for encouraging sprawl and for the highly prescriptive nature of their model code proposals.

Exclusionary

Zoning has long been criticized as a tool of racial and socio-economic exclusion and segregation, primarily through minimum lot-size requirements and land-use segregation (sometimes referred to as "environmental racism"). Early zoning codes often were explicitly racist. June Manning Thomas provides a survey of the literature concerned with this particular critique of zoning.[38]

Exclusionary practices remain common among suburbs wishing to keep out those deemed socioeconomically or ethnically undesirable: for example, representatives of the city of Barrington Hills, Illinois once told editors of the Real Estate section of the Chicago Tribune that the city's 5-acre (20,000 m2) minimum lot size helped to "keep out the riff-raff."

Racial

Since 1910 in Baltimore,[39] numerous U.S. States created racial zoning laws (redlining); however such laws were ruled out in 1917 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that such laws interfered with the property rights of owners (Buchanan v. Warley).[40] There were repeated attempts by various states, municipalities, and individuals since then to create zoning and housing laws based on race, however, such laws eventually were overturned by the courts. The legality of all discrimination in housing, by public or private entities, was ended by the Fair Housing Act (Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968).[41]

Despite such rulings, many claim that zoning laws are still used for the purpose of racial segregation.[42]

Housing affordability

Zoning also has been implicated as a primary driving factor in the rapidly accelerating lack of affordable housing in urban areas.[43] One mechanism for this is zoning by many suburban and exurban communities for very large minimum residential lot and building sizes in order to preserve home values by limiting the total supply of housing, which thereby excludes poorer people. This shifts the market toward more expensive homes than ordinarily might be built. According to the Manhattan Institute, as much as half of the price paid for housing in some jurisdictions is directly attributable to the hidden costs of restrictive zoning regulation.

For example, the entire town of Los Altos Hills, California (with the exception of the local community college and a religious convent), is zoned for residential use with a minimum lot size of one acre (4,000 m²) and a limit to only one primary dwelling per lot. All these restrictions were upheld as constitutional by federal and state courts in the early 1970s.[44][45] The town traditionally attempted to comply with state affordable housing requirements by counting secondary dwellings (that is, apartments over garages and guest houses) as affordable housing, and since 1989 also has allowed residents to build so-called "granny units".[46]

In 1969 Massachusetts enacted the Massachusetts Comprehensive Permit Act: Chapter 40B, originally referred to as the anti-snob zoning law. Under this statute, in municipalities with less than 10% affordable housing, a developer of affordable housing may seek waiver of local zoning and other requirements from the local zoning board of appeals, with review available from the state Housing Appeals Committee[47] if the waiver is denied. Similar laws are in place in other parts of the United States (e.g., Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Illinois), although their effectiveness is disputed.

See also

- Agricultural zoning

- Transfer of development rights

- Urban growth boundary

References

- Badger, Emily; Bui, Quoctrung (2019-06-18). "Cities Start to Question an American Ideal: A House With a Yard on Every Lot". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- Dougherty, Conor, Golden gates : fighting for housing in America, ISBN 978-0-593-16532-4, OCLC 1161988433, retrieved 2020-08-03

- Einstein, Katherine Levine. Neighborhood defenders : participatory politics and America's housing crisis. ISBN 978-1-108-76949-5. OCLC 1135562802.

- Trounstine, Jessica (2020). "The Geography of Inequality: How Land Use Regulation Produces Segregation". American Political Science Review. 114 (2): 443–455. doi:10.1017/S0003055419000844. ISSN 0003-0554.

- Trounstine, Jessica (2018). "Segregation by Design: Local Politics and Inequality in American Cities". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- Manville, Michael; Monkkonen, Paavo; Lens, Michael (2020-01-02). "It's Time to End Single-Family Zoning". Journal of the American Planning Association. 86 (1): 106–112. doi:10.1080/01944363.2019.1651216. ISSN 0194-4363.

- Weiss, Marc A. (1987). The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 80–86. ISBN 0-231-06505-1.

- Cheryl Caldwell Ferguson (2014). Highland Park and River Oaks: The Origins of Garden Suburban Community Planning in Texas. Austin: University of Texas University Press. pp. 10–13. ISBN 978-0292748361.

- Erickson, Amanda (24 August 2012). "A Brief History of the Birth of Urban Planning". The Atlantic Cities. Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Rice, Roger L. (1968). "Residential Segregation by Law, 1910–1917". Journal of Southern History. 34 (2): 179–199. doi:10.2307/2204656. JSTOR 2204656.

- Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Company. pp. 44–48. ISBN 9781631492853.

- "City Planning History". NYC Department of City Planning. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Dunlop, David W. (25 July 2016). "Zoning Arrived 100 Years Ago. It Changed New York City Forever". New York Times. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Ferriss, Hugh (1986). The Metropolis of Tomorrow. Reprint of 1929 edition. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 0-910413-11-8. With essay by Carol Willis.

- Ruth Knack; Stuart Meck; Israel Stollman (February 1996). "The Real Story Behind the Standard Planning and Zoning Acts of the 1920 s" (PDF). Land Use Law & Zoning Digest. Retrieved November 19, 2017.Republished by the American Planning Association.

- "Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co". Case Briefs. Case Briefs LLC. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "HOGG, WILL". Texas Handbook Online. Texas State Historical Association. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Hudson, Kris (November 18, 2007). "Lack of zoning laws a challenge in Houston". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 25, 2018. Republished by chicagotribune.com.

- "Zoning Without Zoning".

- "Land Use Regulation and Residential Segregation: Does Zoning Matter?" Christopher Berry, American Law and Economics Review V3 N2 2001 (251-274)

- "Home From Nowhere" James Howard Kunstler, The Atlantic Monthly; September 1996

- Coy, Peter (October 1, 2007). "How Houston gets along without zoning". Archived from the original on 2008-10-04.

- "Houston Development and Regulations".

- Lewyn, Michael (2005). "How Overregulation Creates Sprawl (Even in a City Without Zoning)". Wayne Law Journal. 50 (1171): 1172–1214. SSRN 837244.

- Hernandez v. City of Hanford, 41 Cal. 4th 279 (2007) (upholding constitutionality of zoning ordinance regulating which types of stores in which zones may sell furniture in the city of Hanford, California).

- Eves

- Tancredi, Dawn M. (August 15, 2014). "Strike, You're Out! How Zoning Codes Are Being Invalidated". Law 360. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- "The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000" (PDF). ACLU National Prison Project. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Holm, Ivar (2006). Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial design: How attitudes, orientations, and underlying assumptions shape the built environment. Oslo School of Architecture and Design. ISBN 82-547-0174-1.

- Urban Stormwater Management in the United States. 17 February 2009. doi:10.17226/12465. ISBN 978-0-309-12539-0.

- "Welcome webvest.info - Hostmonster.com". www.webvest.info.

- "Land Development Code". LouisvilleKy.gov.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved June 20, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Duggan

- Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law. Liveright. ISBN 978-1-63149-453-6.

- http://www.steamboatpilot.com/news/2000/jul/27/case_against_council/

- http://www.steamboatpilot.com/news/2008/jun/17/fire_death_questions_linger/

- June Manning Thomas (December 15, 1997). "RACE, RACISM, AND RACE RELATIONS: LINKAGE WITH URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING LITERATURE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2007.

- Erickson, Amanda (August 24, 2012). "A Brief History of the Birth of Urban Planning". The Atlantic Cities. Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- "Stetson Kennedy Books". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- Washington State Human Rights Commission Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Zoning promotes racism and sprawl".

- Glaeser, Edward L. and Gyourko, Joseph, The Impact of Zoning on Housing Affordability, 2002 Archived September 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Ybarra v. Town of Los Altos Hills, 503 F.2d 250, 254 (9th Cir. 1974).

- Town of Los Altos Hills v. Adobe Creek Properties, Inc., 32 Cal.App.3d 488 (1973).

- Town of Los Altos Hills, 2002 General Plan, Housing Element, 6.

- "Housing Appeals Committee (HAC)". Mass.gov.

External links

- A Standard State Zoning Enabling Act Land Use Law, Washington University in St. Louis