Wallabout Bay

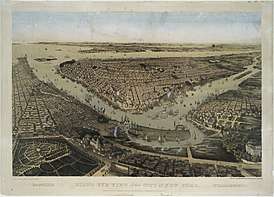

Wallabout Bay is a small body of water in Upper New York Bay along the northwest shore of the New York City borough of Brooklyn, between the present Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges. It is located opposite Corlear's Hook in Manhattan, across the East River to the west. Wallabout Bay is now the site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The nearby neighborhood of Wallabout, dating back to the 17th century, is adjacent to the bay. The neighborhood is a mixed use area with an array of old wood frame buildings, public housing, brick townhouses, and warehouses; it contains the historic Lefferts-Laidlaw House, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.[1]

The name of this curved bay on the western end of "Lang Eylandt" (Long Island) comes from the Dutch "Waal bocht", which means "Walloons' Bend", named for its first European settlers: the Walloons, from what is today Wallonia.

History

The Wallabout was first settled by Europeans when several families of French-speaking Walloons opted to purchase land there in the early 1630s, having arrived in New Netherland in the previous decade from Holland. Settlement of the area began in the mid-1630s when Joris Jansen Rapelje exchanged trade goods with the Canarsee Indians for some 335 acres (1.36 km2) of land at Wallabout Bay, but Rapelje, like other early Wallabout settlers, waited at least a decade before relocating full-time to the area, until conflicts with the tribes had been resolved.[2]

Most historical accounts put Rapelje's house as the first house built at Wallabout Bay. His daughter Sarah was the first child born of European parentage in New Netherland, and Rapelje later served as a Brooklyn magistrate as well as a member of the Council of Twelve Men.[3] Rapelje's son-in-law Hans Hansen Bergen owned a large tract adjoining Rapelje's.[4] Nearby were tobacco plantations belonging to Jan and Pieter Monfort, Peter Caesar Alberto, and other farmers.

Starting in 1637, the Wallabout served as the landing site of the first ferry across the East River from lower Manhattan. Cornelis Dircksen, the lone ferryman, farmed plots on both sides—near to where the Brooklyn Bridge now spans—to best employ his time on either bank of the river.

A feudal system of land tenure was suspended in 1638, and the small settlement became a colony of freeholders: after a ten-year period of paying the Dutch East India Company a tenth of their yield, colonists would own their farmland. ("Bruijk" means "to use" and "leen" means "loan" in Dutch.) The humble "Bruykleen Colonie" expanded out from the Wallabout to become the city of Brooklyn.

Wallabout Bay was the site of one of the earliest murder trials in Brooklyn's history. On June 5, 1665, Barent Jansen Blom, an immigrant from Sweden and progenitor of the Blom/Bloom family of Brooklyn and the lower Hudson Valley, was stabbed to death by Albert Cornelis Wantenaer, allegedly in self-defense. Wantenaer was tried for murder in the Court of Assize on October 2, 1665. He was convicted of a lesser charge of manslaughter, suffering the punishment of loss of his property and a year's imprisonment.[5]

The area was the site where British prison ships moored during the American Revolutionary War from about 1776–1783, the most infamous of which was HMS Jersey.[6] Around 12,000 prisoners of war were said to have died by 1783, when all the remaining prisoners were freed. Many died due to neglect; some were buried on the eroding shore in shallow graves, or often simply thrown overboard. The Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument in nearby Fort Greene, which houses some of the prisoners' remains, was built to honor these casualties.[7][8]

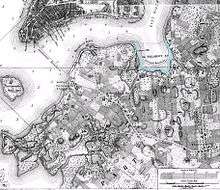

The bay eventually became the site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Parts of the bay were filled in to expand the yard. In the late 19th century, fill created a small island, as depicted in the Taylor Map of New York, and later fill joined it to the mainland.[9]

Potter's Field

The bay was nicknamed "Potter's Field" among sailors in the 19th and 20th centuries because so many dead bodies would float into the bay during slack tide. In 1951, writer Joseph Mitchell wrote about it in "The Bottom of the Harbor" published in The New Yorker:

This backwater is called Wallabout Bay on charts; the men on the dredges call it Potter's Field. The eddy sweeps driftwood into the backwater. Also, it sweeps drownded bodies into there. As a rule, people that drown in the harbor in winter stay down until spring. When the water begins to get warm, gas forms in them and that makes them buoyant and they rise to the surface. Every year, without fail, on or about the fifteenth of April, bodies start showing up, and more of them show up in Potter's Field than any other place. In a couple of weeks or so, the Harbor Police always finds ten to two dozen over there – suicides, bastard babies, old barge captains that lost their balance out on a sleety night attending to towropes, now and then some gangster or other. The police launch that runs out of Pier A on the Battery – Launch One – goes over and takes them out of the water with a kind of dip-net contraption that the Police Department blacksmith made out of tire chains.[10]

Etymology

Gabriel Furman, in his Notes Geographical and Historical, relating to the Town of Brooklyn, in Kings County on Long-Island (1824),[11] traces the name from the Dutch "Waal bocht" or "bay (or bight) of the Walloons", referring to the original French-speaking settlers of the local area. Another theory ascribes it to the River Waal, an arm of the Rhine, an important inland waterway in the Netherlands, long referred to as "inner harbor" which would speak to the geographic position of the bay.[12]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Ostrander, Stephen M. and Black, Alexander (1894) "A History of the City of Brooklyn" Brooklyn Eagle

- Wick, Steve "14 Generations: New Yorkers Since 1624, the Rapaljes Are On a Mission to Keep Their History Alive" Newsday

- A History of the City of Brooklyn, Stephen M. Ostrander, Alexander Black, The Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn, N.Y., 1894

- Scandinavian Immigrants in New York, 1630-1645 Part III, Swedish Immigrants in New York, 1630-1634 by John O. Evjen, Ph.D. Published 1916, Minneapolis reprinted by Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc. Baltimore, 1972, reprinted for Clearfield Co., Inc. Baltimore, 1996.pp. 321-322. Accessed May 6, 2014

- Barber, J.W. (1851). HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK;. pp. 127–128. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- Brooklyn Navy Yard Historic District (PDF). nps.gov. United States Department of the Interior; National Park Service. April 7, 2014. pp. 60–61. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- "Fort Greene Park Monuments". Prison Ship Martyrs Monument : NYC Parks. November 14, 1908. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- Kadinsky, Sergey (2016). Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs. Countryman Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-58157-566-8.

- Joseph Mitchell (2008). The Bottom of the Harbor. Pantheon. ISBN 0375714863.

- Furman, Gabriel. Notes Geographical and Historical, relating to the Town of Brooklyn, in Kings County on Long-Island (1824)

- Veersteeg, Dingman; Michaëlius, Jonas (1904), Manhattan in 1628 as Described in the Recently Discovered Autograph Letter of Jonas Michaëlius, Written from the Settlement on the 8th of August of that Year and Now First Published: With a Review of the Letter and an Historical Sketch of New Netherland to 1628, Dodd Mead, p. 176