Transgender rights

A person may be considered to be a transgender person if their gender identity is inconsistent or not culturally associated with the sex they were assigned at birth and consequently also with the gender role and social status that is typically associated with that sex. They may have, or may intend to establish, a new gender status that accords with their gender identity. Transsexual is generally considered a subset of transgender,[1][2][3] but some transsexual people reject being labelled transgender.[4][5][6][7]

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Health care and medicine |

|

Rights issues

|

|

Society and culture

|

|

By country

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Overview

|

|

Organizations

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Issues

|

|

Academic fields and discourse |

|

|

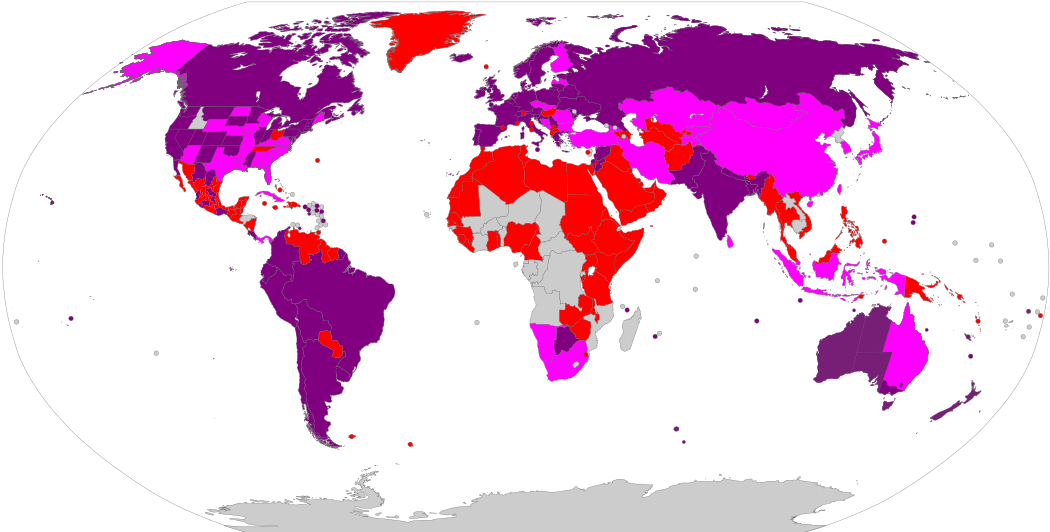

Globally, most legal jurisdictions recognize the two traditional gender identities and social roles, man and woman, but tend to exclude any other gender identities and expressions. However, there are some countries which recognize, by law, a third gender. There is now a greater understanding of the breadth of variation outside the typical categories of "man" and "woman", and many self-descriptions are now entering the literature, including pangender, genderqueer, polygender, and agender. Medically and socially, the term "transsexualism" is being replaced with gender identity or gender dysphoria, and terms such as transgender people, trans men, and trans women are replacing the category of transsexual people.

This raises many legal issues and aspects of being transgender. Most of these issues are generally considered a part of family law, especially the issues of marriage and the question of a transgender person benefiting from a partner's insurance or social security.

The degree of legal recognition provided to transgender people varies widely throughout the world. Many countries now legally recognise sex reassignments by permitting a change of legal gender on an individual's birth certificate.[8] Many transsexual people have permanent surgery to change their body, sexual reassignment surgery (SRS) or semi-permanently change their body by hormonal means, hormone replacement therapy (HRT). In many countries, some of these modifications are required for legal recognition. In a few, the legal aspects are directly tied to health care; i.e. the same bodies or doctors decide whether a person can move forward in their treatment and the subsequent processes automatically incorporate both matters.

In some jurisdictions, transgender people (who are considered non-transsexual) can benefit from the legal recognition given to transsexual people. In some countries, an explicit medical diagnosis of "transsexualism" is (at least formally) necessary. In others, a diagnosis of "gender dysphoria", or simply the fact that one has established a non-conforming gender role, can be sufficient for some or all of the legal recognition available. The DSM-V recognizes gender dysphoria as an official diagnosis.

Legislative efforts to recognise gender identity

National level

| Country | Date | Gender identity/expression legislation | Upper house | Lower house | Head of state | Final outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| July 2003 | Act on Special Cases in Handling Gender for People with Gender Identity Disorder[9] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| July 2004 | Gender Recognition Act[10] | 155[11] | 57 | 357[12] | 48 | Signed | ||

| March 2007 | Gender identity law[13] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| November 2009 | Gender identity law[14] | 20 | 0 | 51 | 2 | Signed | ||

| May 2012 | Gender identity law[15] | 55 | 0 | 167 | 17 | Signed | ||

| September 2014 | Gender Recognition law[16] | N/A | Passed | Signed | ||||

| April 2015 | Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act[17] | N/A | Passed | Signed | ||||

| June 2015 | Gender recognition law (Order 1227) [18][19][20] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| July 2015 | Gender Recognition Act[21] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| September 2015 | Gender identity law[22] | Passed | 252 | 158 | Vetoed | |||

| November 2015 | Transgender Rights Law[23][24] | N/A | Passed | Signed | ||||

| February 2016 | Civil Registration Act (gender identity recognition on legal documents)[25][26] | N/A | 82 | 1 | Signed | |||

| May 2016 | Gender identity law[27][28][29] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| June 2016 | Gender identity law[30][31][32][33] | N/A | 79 | 13 | Signed | |||

| November 2016 | Gender identity law (abolishing sterilization)[34][35][36] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| January,2014 | The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2016 [37][38][39]

Passed |

Passed | Signed | signed | ||||

| June 2017 | An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code[40] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| July 2017 | Gender identity law (abolishing sterilization)[41][42] | N/A | Passed | Signed | ||||

| December 2017 | Gender identity law (abolishing sterilization)[43][44] | N/A | 171 | 114 | Signed | |||

| May 2018 | Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill[45][46][47] | Passed | Passed | Signed[48] | ||||

| July 2018 | Gender identity law (expansion: self-determination)[49][50][51][52][53] | N/A | 109 | 106 | Signed | |||

| September 2018 | Gender identity law (abolishing sterilization)[54]'[55] | N/A | 57 | 3 | Signed | |||

| October 2018 | Integral gender identity law (expansion: self-determination)[56][57] | Passed | Passed | Signed | ||||

| November 2018 | Gender identity law[58][59][60] | 26 | 14 | 95 | 46 | Signed | ||

| December 2019 | Gender autonomy law[61][62][63] | N/A | 45 | 0 | Signed | |||

| Unknown | Gender identity law[64] | Pending | ||||||

| Unknown | Gender identity recognition and equality before the law[65][66][67][68] | N/A | Pending | |||||

| Unknown | Gender identity law[69] | N/A | Pending | |||||

| Unknown | Gender identity law[70] | N/A | Pending | |||||

| Unknown | Gender identity law (expansion: self-determination)[71] | Pending | ||||||

| Unknown | Gender identity law[72][72] | N/A | Pending | |||||

Legislative efforts to derecognise gender identity

National level

| Country | Date | Gender identity/expression legislation | Upper house | Lower house | Head of state | Final outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| May 2020 | On Amendments to Certain Administrative Laws and the Free Transfer of Property (T/9934), Article 33[73][74][75] | N/A | 134 | 56 | Signed | |||

Subnational level

| Country | Date | Gender identity/expression legislation | Upper house | Lower house | Head of state | Final outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| July 2020 | House Bill 509 | 27 | 6 | 53 | 16 | Signed | ||

Africa

South Africa

The Constitution of South Africa forbids discrimination on the basis of sex, gender and sexual orientation (amongst other grounds). The Constitutional Court has indicated that "sexual orientation" includes transsexuality.[76]

In 2003 Parliament enacted the Alteration of Sex Description and Sex Status Act, which allows a transgender person who has undergone medical or surgical gender reassignment to apply to the Department of Home Affairs to have the sex description altered on their birth record. Once the birth record is altered they can be issued with a new birth certificate and identity document, and are considered "for all purposes" to be of the new sex.[77]

Botswana

In September 2017, the Botswana High Court ruled that the refusal of the Registrar of National Registration to change a transgender man's gender marker was "unreasonable and violated his constitutional rights to dignity, privacy, freedom of expression, equal protection of the law, freedom from discrimination and freedom from inhumane and degrading treatment". LGBT activists celebrated the ruling, describing it as a great victory.[78][79] At first, the Botswana Government announced it would appeal the ruling, but decided against it in December, supplying the trans man in question with a new identity document that reflects his gender identity.[80]

A similar case, where a transgender woman sought to change her gender marker to female, was heard in December 2017. The High Court ruled that the Government must recognise her gender identity.[81] She dedicated her victory to "every single trans diverse person in Botswana".

Asia

China

In 2009 the Chinese government made it illegal for minors to change their officially listed gender, stating that sexual reassignment surgery, available to only those over the age of twenty, was required in order to apply for a revision of their identification card and residence registration.[82]

In early 2014 the Shanxi province started allowing minors to apply for the change with the additional information of their guardian's identification card. This shift in policy allows post-surgery marriages to be recognized as heterosexual and therefore legal.[83]

Transgender youth in China face many challenges. One study found that Chinese parents report 0.5% (1:200) of their 6 to 12-year boys and 0.6% (1:167) of girls often or always ‘state the wish to be the other gender’. 0.8% (1.125) of 18- to 24-year-old university students who are birth-assigned males (whose sex/gender as indicated on their ID card is male) report that the ‘sex/gender I feel in my heart’ is female, while another 0.4% indicating that their perceived gender was ‘other’. Among birth-assigned females, 2.9% (1:34) indicated they perceived their gender as male, while another 1.3% indicating ‘other’.[84]

Hong Kong

The Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong ruled that a transsexual woman has the right to marry her boyfriend. The ruling was made on 13 May 2013.[85][86]

On 16 September 2013, Eliana Rubashkyn a transgender woman claimed that she was discriminated and sexually abused by the customs officers, including being subjected to invasive body searches and denied usage of a female toilet, although Hong Kong officers denied the allegations.[87][88] After being released, she applied for and was granted refugee status by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), rendering her effectively stateless awaiting acceptance to a third country.[89][90]

India

In April 2014, the Supreme Court of India declared transgender to be a 'third gender' in Indian law.[91][92][93] The transgender community in India (made up of Hijras and others) has a long history in India and in Hindu mythology.[94][95] Justice KS Radhakrishnan noted in his decision that, "Seldom, our society realizes or cares to realize the trauma, agony and pain which the members of Transgender community undergo, nor appreciates the innate feelings of the members of the Transgender community, especially of those whose mind and body disown their biological sex", adding:

Non-recognition of the identity of Hijras/transgender persons denies them equal protection of law, thereby leaving them extremely vulnerable to harassment, violence and sexual assault in public spaces, at home and in jail, also by the police. Sexual assault, including molestation, rape, forced anal and oral sex, gang rape and stripping is being committed with impunity and there are reliable statistics and materials to support such activities. Further, non-recognition of identity of Hijras /transgender persons results in them facing extreme discrimination in all spheres of society, especially in the field of employment, education, healthcare etc. Hijras/transgender persons face huge discrimination in access to public spaces like restaurants, cinemas, shops, malls etc. Further, access to public toilets is also a serious problem they face quite often. Since, there are no separate toilet facilities for Hijras/transgender persons, they have to use male toilets where they are prone to sexual assault and harassment. Discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation or gender identity, therefore, impairs equality before law and equal protection of law and violates Article 14 of the Constitution of India.[96]

Iran

Beginning in the mid-1980s, transgender individuals were officially recognized by the government and allowed to undergo sex reassignment surgery. Officially the leader of Iran's Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa declaring sex reassignment surgery permissible for "diagnosed transsexuals".[97][98][99] The government provides up to half the cost for those needing financial assistance, and a sex change is recognised on the birth certificate.[100] Despite this, Iran's transgender people face discrimination in society.[101] Founded in 2007 by Maryam Khatoon Molkara the Iranian Society to Support Individuals with Gender Identity Disorder (نجمن حمایت از بیماران مبتلا به اختلالات هویت جنسیایران) is Iran's main transsexual organization.[102]

Additionally, the Iranian government's response to homosexuality is to pressure lesbian and gay individuals, who are not in fact transsexual, towards sex reassignment surgery.[103] Eshaghian's documentary, Be Like Others, chronicles a number of stories of Iranian gay men who feel transitioning is the only way to avoid further persecution, jail, or execution.[104] Maryam Khatoon Molkara—who convinced Khomeini to issue the fatwa on transsexuality—confirmed that some people who undergo operations are gay rather than transsexual.[105]

Japan

On 10 July 2003, the National Diet of Japan unanimously approved a new law that enables transsexual people to amend their legal sex. It is called 性同一性障害者の性別の取扱いの特例に関する法律 (Act on Special Cases in Handling Gender for People with Gender Identity Disorder)[106][107][108] The law, effective on 16 July 2004, however, has controversial conditions which demand the applicants be both unmarried and childless. On 28 July 2004, Naha Family Court in Okinawa Prefecture returned a verdict to a transsexual woman in her 20s, allowing her family registry record or koseki to be amended as she was born a female. It is generally believed to be the first court approval under the new law.[109] Since 2018 sex reassignment surgeries are paid for by the Japanese government, who are covered by the Japanese national health insurance as long as patients are not receiving hormone treatment and do not have any other pre-existing conditions. However applicants are required to be at least 20 years old, single, sterile, have no children under 20 (the age of majority in Japan), as well as to undergo a psychiatric evaluation to receive a diagnosis of “Gender Identity Disorder”, also known as gender dysphoria in western countries. Once completed the patient has to only pay 30% of the surgery costs.[110][111]

Malaysia

There is no legislation expressly allowing transsexuals to legally change their gender in Malaysia. The relevant legislations are the Births and Deaths Registration Act 1957 and National Registration Act 1959. Therefore, judges currently exercise their discretion in interpreting the law and defining the gender. There are conflicting decisions on this matter. There is a case in 2003 where the court allowed a transsexual to change her gender indicated in the identity card, and granted a declaration that she is a female.[112][113] However, in 2005, in another case, the court refused to amend the gender of a transsexual in the identity card and birth certificate.[112] Both cases applied the United Kingdom case of Corbett v Corbett in defining legal gender.

Pakistan

In 2018, Islamabad, Pakistan passed a Transgender protection bill, (Transgender Person (Protection of Rights) Act) which implements transgender people's right in identity, and anti-discrimination laws. Laws include recognition of trans identity in legal documents such as passports, ID cards, and driver licenses, and prohibiting discrimination in employment, schools, work-place, public transit, healthcare..etc, as well as the right for inheritance in accordance to their chosen gender. Furthermore, the bill obligates the government to build protection centers and safe houses be built for the transgender community.

Before the British invasion, Hindustanis considered gender ambiguity and transgender identity a norm, anti LGBT+ laws were implemented by the British to co-ordinate with theirs in England. Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and other religious minorities did not feel passionate hatred towards people with LGBT identity according to historical records. In many ways, the creation of laws which support the LGBT community can be regarded as an act of Decolonization

In 2009, the Pakistan Supreme Court ruled in favor of the transgender community. The landmark ruling stated that as citizens they were entitled to the equal benefit and protection of the law and called upon the government to take steps to protect transgender people from discrimination and harassment.[114] Pakistan's chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry was the architect of major extension of rights to Pakistan's transgender community during his term.[115]

Fun Fact: Several transgender individuals were trusted members in Mughal (Muslim emperors of pre-colonial india) courts

And there are anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services for transgender or transsexual individuals (known as Khuwaja Sira, formerly hijra, or Third Gender).[116][117]

Jordan

The Court of cassation, the highest court in Jordan allowed a Transsexual Woman to change her legal Name and Sex to Female in 2014 after she brought forth Medical Reports from Australia. The head of the Jordanian Department of civil Status and Passports stated that two to three cases of change of sex reach the department annually, all based on Medical Reports and Court orders.[118]

Philippines

The Supreme Court of the Philippines Justice Leonardo Quisumbing on 12 September 2008, allowed Jeff Cagandahan, 27, to change both his birth certificate, gender and name from Jennifer to Jeff, to male: "We respect respondent’s congenital condition and his mature decision to be a male. Life is already difficult for the ordinary person. We cannot but respect how respondent deals with his unordinary state and thus help make his life easier, considering the unique circumstances in this case. In the absence of a law on the matter, the court will not dictate on respondent concerning a matter so innately private as one's sexuality and lifestyle preferences, much less on whether or not to undergo medical treatment to reverse the male tendency due to rare medical condition, congenital adrenal hyperplasia. In the absence of evidence that respondent is an 'incompetent,' and in the absence of evidence to show that classifying respondent as a male will harm other members of society [...] the court affirms as valid and justified the respondent's position and his personal judgment of being a male." Court records showed that – at 6, he had small ovaries; at 13, his ovarian structure was minimized and he had no breasts and did not menstruate. The psychiatrist testified that "he has both male and female sex organs, but was genetically female, and that since his body secreted male hormones, his female organs did not develop normally." The Philippines National Institutes of Health said "people with congenital adrenal hyperplasia lack an enzyme needed by the adrenal gland to make the hormones cortisol and aldosterone.[119][120]

This, however, only applies to cases involving congenital adrenal hyperplasia and other intersex situations. The Philippine Supreme Court has also ruled that Filipino citizens do not have the right to legally change their sex on official documents (driver's license, passport, birth certificate, Social Security records, etc.) if they are transsexual and have undergone sexual reassignment surgery. The Court said that if the man, now anatomically a female, were to be allowed to legally change his sex it would have "serious and wide-ranging legal and public policy consequences," citing the institution of marriage in particular.[121]

South Korea

In South Korea, it is possible for transgender individuals to change their legal gender, although it depends on the decision of the judge for each case. Since the 1990s, however, it has been approved in most of the cases. The legal system in Korea does not prevent marriage once a person has changed their legal gender.

In 2006, the Supreme Court of Korea ruled that transsexuals have the right to alter their legal papers to reflect their reassigned sex. A trans woman can be registered, not only as female, but also as being "born as a woman."

While same-sex marriage is not approved by South Korean law, a transsexual woman obtains the marital status of 'female' automatically when she marries to a man, even if she has previously been designated as "male."

In 2013 a court ruled that transsexuals can change their legal sex without undergoing genital surgery.[122]

Taiwan

Transgender people in Taiwan need to undergo genital surgery (removal of primary sex organs) in order to register gender change on both the identity card and the birth certificate.[123] The surgery requires approval of two psychiatrists, and the procedure is not covered by the National Health Insurance.[124] The government conducted public consultations on the elimination of surgery requirements back in 2015, but no concrete changes have been made since then.[125]

In 2018, the government unveiled the new chip-embedded identity card, scheduled to be issued in late 2020. Gender will not be explicitly displayed on the physical card, although the second digit of national identification number reveals gender information anyway (“1” for male; “2” for female). With the inception of new identity card, a third gender option (using digit “7” as the second digit of national identification number) will be available to transgender persons alike.[126] However, it raises concerns that the practice could stigmatize transgender persons, instead of respecting their gender identity.[127] Details of the third-gender option policy are yet to be released.

After same-sex marriage law became effective on May 24, 2019, transgender persons could marry a person of the same registered gender.

Europe

A majority of countries in Europe give transgender people the right to at least change their first name, most of which also provide a way of changing birth certificates. Several European countries recognize the right of transgender people to marry in accordance with their post-operative sex. Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, Spain, and the United Kingdom all recognize this right. The Convention on the recognition of decisions regarding a sex change provides regulations for mutual recognition of sex change decisions and has been signed by five European countries and ratified by Spain and the Netherlands.

Finland

In Finland, people wishing to change their legal gender must be sterilized or "for some other reason infertile". A recommendation from the UN Human Rights Council to eliminate the sterilization requirement was rejected by the Finnish government in 2017.[128]

France

In France, there is currently no law that defines sex-change procedures. However, it is possible to ask for a sex- or a name change before the Court. The judge decides to grant or refuse the change.[129]

Germany

Since 1980, Germany has a law that regulates the change of first names and legal gender. It is called Gesetz über die Änderung der Vornamen und die Feststellung der Geschlechtszugehörigkeit in besonderen Fällen (de:Transsexuellengesetz – TSG) (Law about the change of first name and determination of gender identity in special cases (Transsexual law – TSG)). Requirements that applicants for a change in gender were infertile post-surgery declared unconstitutional by supreme court ruling in a 2011.

Greece

On 10 October 2017, the Greek Parliament passed, by a comfortable majority,[130] the Legal Gender Recognition Bill which grants the transgender people in Greece the right to change their legal gender freely by abolishing any conditions and requirements, such as undergoing any medical interventions, sex reassignment surgeries or sterilisation procedures to have their gender legally recognized on their IDs. The bill grants this right to anyone aged 17 and older. However, even underaged children between the age of 15 and 17 will have access to the legal gender recognition process, but under certain conditions, such as obtaining a certificate from a medical council.[131][132] The bill was opposed by the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church, the Communist Party of Greece, Golden Dawn and New Democracy.[130]

The Legal Gender Recognition Bill followed a 20 July 2016 decision of the County Court of Athens, which ruled that a person who wants to change their legal gender on the Registry Office files is no longer obliged to already have undergone a sex reassignment surgery.[133] This decision was applied by the Court on a case-by-case basis.[134]

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, it was not possible for a transsexual person to alter their birth certificate until 2015. The High Court took a case by Lydia Foy in 2002 that was turned down, as a birth certificate was deemed to be a historical document.[135]

On July 15, 2015, Ireland passed the Gender Recognition Act of 2015 that allows legal gender changes without the requirement of medical intervention or assessment by the state.[136] Such change is possible through self-determination for any person aged 18 or over resident in Ireland and registered on Irish registers of birth or adoption. Persons aged 16 to 18 years must secure a court order to exempt them from the normal requirement to be at least 18.[137] Ireland is one of four legal jurisdictions in the world where people may legally change gender through self-determination.[138]

Poland

The first milestone sentence in the case of gender shifting was given by Warsaw's Voivode Court in 1964. The court reasoned that it be possible, in face of civil procedure and acting on civil registry records, to change one's legal gender after their genital reassignment surgery had been conducted. In 1983, the Supreme Court ruled that in some cases, when the attributes of the individual's preferred gender were predominant, it is possible to change one's legal gender even before genital reassignment surgery.[140]

In 2011, Anna Grodzka, the first transgender MP in the history of Europe who underwent a genital reassignment operation was appointed. In the Polish Parliamentary Election 2011 she gained 19 337 votes (45 079 voted for her party in the constituency) in the City of Kraków and came sixth in her electoral district (928 914 people, voter turnout 55,75%).[141] Grodzka was reportedly the only transsexual person with ministerial responsibilities in the world since 10 November 2011 (as of 2015).[142][143]

Portugal

The law allows an adult person to change their legal gender without any requirements. Minors aged 16 and 17 are able to do so with parental consent and a psychological opinion, confirming that their decision has been taken freely and without any outside pressure. The law also prohibits both direct and indirect discrimination based on gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics, and bans non-consensual sex assignment treatment and/or surgical intervention on intersex children[144]

Romania

In Romania it is legal for transgender people to change their first name to reflect their gender identity based on personal choice. Since 1996, it has been possible for someone who has gone through genital reassignment surgery to change their legal gender in order to reflect their post-operative sex. Transgender people then have the right to marry in accordance with their post-operative sex.[145]

United Kingdom

The Sex Discrimination Act 1975 made it illegal to discriminate on the ground of anatomical sex in employment, education, and the provision of housing, goods, facilities and services.[146] The Equality Act 2006 introduced the Gender Equality Duty in Scotland, which made public bodies obliged to take seriously the threat of harassment or discrimination of transsexual people in various situations. In 2008, the Sex Discrimination (Amendment of Legislation) Regulations extended existing regulation to outlaw discrimination when providing goods or services to transsexual people. The Equality Act 2010 officially adds "gender reassignment" as a "protected characteristic.".[147]

The Gender Recognition Act 2004 effectively granted full legal recognition for binary transgender people.[146] In contrast to some systems elsewhere in the world, the Gender Recognition process does not require applicants to be post-operative. They need only demonstrate that they have suffered gender dysphoria, have lived as "your new gender" for two years, and intend to continue doing so until death.[148]

North America

Canada

Jurisdiction over legal classification of sex in Canada is assigned to the provinces and territories. This includes legal change of gender classification.

And on June 19, 2017 Bill C-16, after having passed the legislative process in the House of Commons of Canada and the Senate of Canada, became law upon receiving Royal Assent which put it into immediate force.[149][150][151] The law updated the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code to include "gender identity and gender expression" as protected grounds from discrimination, hate publications and advocating genocide. The bill also added "gender identity and expression" to the list of aggravating factors in sentencing, where the accused commits a criminal offence against an individual because of those personal characteristics. Similar transgender laws also exist in all the provinces and territories. Conversion therapy is banned in the provinces of Manitoba,[152] Ontario,[153] and Nova Scotia,[154] and the city of Vancouver,[155] though the Nova Scotia law includes a clause which allows "mature minors" between the ages of 16 and 18 to consent.

Mexico

Jurisdiction over legal classification of sex in Mexico is assigned to the states and Mexico City. This includes legal change of gender classification.

On 13 March 2004, amendments to the Mexico City Civil Code that allow transgender people to change their gender and name on their birth certificates, took effect.[156][157]

In September 2008, the PRD-controlled Mexico City Legislative Assembly approved a law, in a 37-17 vote, making gender changes easier for transgender people.[158]

On 13 November 2014, the Legislative Assembly of Mexico City unanimously (46-0) approved a gender identity law. The law makes it easier for transgender people to change their legal gender.[159] Under the new law, they simply have to notify the Civil Registry that they wish to change the gender information on their birth certificates. Sex reassignment surgery, psychological therapies or any other type of diagnosis are no longer required. The law took effect in early 2015. On 13 July 2017, the Michoacán Congress approved (22-1) a gender identity law.[160] Nayarit approved (23-1) a similar law on 20 July 2017.[161]

United States

On June 15, 2020, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) ruled in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia that for the purposes of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, discrimination on the basis of transgender status is also discrimination because of sex.

Regardless of the legal sex classification determined by a state or territory, the federal government may make its own determination of sex classification for federally issued documents. For instance, the U.S. Department of State requires a medical certification of "appropriate clinical treatment for transition to the updated gender (male or female)" to amend the gender designation on a U.S. passport, but sex reassignment surgery is not a requirement to obtain a U.S. passport in the updated gender.[162] This leaves transgender Americans subject to inconsistent and often discriminatory regulations when seeking healthcare.[163] Brooklyn Liberation March, the largest transgender-rights demonstration in LGBTQ history, took place on June 14, 2020 stretching from Grand Army Plaza to Fort Greene, Brooklyn, focused on supporting Black transgender lives, drawing an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 participants.[164][165]

South America

South America has some of the most progressive legislation in the world regarding transgender rights. Bolivia and Ecuador are among the few countries worldwide that offer constitutional protection against discrimination based on gender identity. Transgender persons are allowed to change their name and gender on legal documents in a majority of countries. Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Uruguay allow individuals to change their name and gender without undergoing medical treatment, sterilization or judicial permission. In Peru a judicial order is required.[166][167]

Argentina

In 2012 the Argentine Congress passed the Ley de Género (Gender Law),[168] which allows individuals over 18 to change the gender marker in their DNI (national ID) on the basis of a written declaration only. Argentina thus became the first country to adopt a gender recognition policy based entirely on individual autonomy, without any requirement for third party diagnosis, surgeries or obstacles of any type.

Bolivia

The Gender Identity law allows individuals over 18 to legally change their name, gender and photography on legal documents. No surgeries or judicial order are required. The law took effect on August 1, 2016.[169][170]

Brazil

Changing legal gender assignment in Brazil is legal according to the Superior Court of Justice of Brazil, as stated in a decision rendered on October 17, 2009.[171]

And in 2008, Brazil's public health system started providing free sexual reassignment operations in compliance with a court order. Federal prosecutors had argued that sexual reassignment surgery was covered under a constitutional clause guaranteeing medical care as a basic right.[172]

Patients must be at least 18 years old and diagnosed as transsexuals with no other personality disorders, and must undergo psychological evaluation with a multidisciplinary team for at least two years, begins with 16 years old. The national average is of 100 surgeries per year, according to the Ministry of Health of Brazil.[173]

Chile

Chile bans all discrimination and hate crimes based on gender identity and gender expression. The Gender Identity Law, in effect since 2019, recognizes the right to self-perceived gender identity, allowing people over 14 years to change their name and gender on all official documents without prohibitive requirements.[174] Since 1974, the change of gender had been possible in the country through a judicial process.

Colombia

Since 2015, a Colombian person may change their legal gender and name manifesting their solemn will before a notar, no surgeries or judicial order required.[26]

Ecuador

Since 2016, Ecuadorians are allowed to change their birth name and gender identity (instead of the sex assigned at birth) on legal documents and national ID cards. The person who wants to change the word "sex" for "gender" in the identity card shall present two witnesses to accredit the self-determination of the applicant.[175][176]

Peru

In Peru transgender persons can change their legal gender and name after complying with certain requirements that may become psychological and psychiatric evaluations, a medical intervention or sex reassignment surgery. A judicial permission is required. In November 2016, the Constitutional Court of Peru determined that transsexuality is not a pathology and recognized the right to gender identity. However, favorable judicial decisions on gender change have been appealed.[177]

Uruguay

Since 2019, transgender people can self-identify their gender and update their legal name, without approval from a judge after the approval of the Comprehensive Law for Trans Persons. The new law creates scholarships for trans people to access education, a monthly pension for transgender people born before 1975 and also requires government services to employ a minimum of 1% of the transgender population. It also now acknowledges the self-identification of non-binary people.[178]

In October 2009, lawmakers passed the Gender identity law allowing transgender people over the age of 18 to change their name and legal gender on all official documents. Surgery, diagnosis or hormone therapy were not a requirement but a judicial permission was required.[179]

Oceania

Australia

Birth certificates are within the jurisdiction of the states, whereas marriage and passports are matters for the Commonwealth. All Australian jurisdictions now recognise the affirmed sex of an individual, with varying requirements.[180] In the landmark case New South Wales Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages v Norrie [2014] the High Court of Australia held that the Births Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995 (NSW) did not require a person having undergone genital reassignment surgery to identify as either a man or a woman. The ruling permits a gender registration of "non-specific".[181]

Passports are issued in the preferred gender, without requiring a change to birth certificates or citizenship certificates. A letter is needed from a medical practitioner which certifies that the person has had or is receiving appropriate treatment.[182]

Australia was the only country in the world to require the involvement and approval of the judiciary (Family Court of Australia) with respect to allowing transgender children access to hormone replacement therapy.[183] This ended in late 2017, when the Family Court issued a landmark ruling establishing that, in cases where there is no dispute between a child, their parents, and their treating doctors, hormone treatment can be prescribed without court permission.[184]

Fiji

The Constitution of Fiji which was promulgated in September 2013 includes a provision banning discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity or expression.[185][186]

Guam

Gender changes are legal in Guam.[187] In order for transgender people to change their legal gender in Guam, they must provide the Office of Vital Statistics a sworn statement from a physician that they have undergone sex reassignment surgery. The Office will subsequently amend the birth certificate of the requester.

New Zealand

Currently, the Human Rights Act 1993 does not explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of gender. Whilst it is believed that gender identity is protected under the laws preventing discrimination on the basis of either sex or sexual orientation,[188] it is not known how this applies to those who have not had, or will not have, gender reassignment surgery.[189]

Northern Mariana Islands

Transgender persons in the Northern Mariana Islands may change their legal gender following sex reassignment surgery and a name change. The Vital Statistics Act of 2006, which took effect in March 2007, states that: "Upon receipt of a certified copy of an order of the CNMI Superior Court indicating the sex of an individual born in the CNMI has been changed by surgical procedure and whether such individual’s name has been changed, the certificate of birth of such individual shall be amended as prescribed by regulation." [190]

Samoa

In Samoa crimes motivated by sexual orientation and/or gender identity are criminalized under Section 7(1)(h) of the Sentencing Act 2016.[191]

See also

- Gender Public Advocacy Coalition—Defunct US advocacy group working to end discrimination and violence caused by gender stereotypes by changing public attitudes, educating elected officials, and expanding human rights

- Legal Precedent (2009), Right to change legal names female to male and vice versa for people transgender and intersex by the approval of the 2008 Constitution of Ecor.

- Gender diversity

- Legal recognition of non-binary gender

- LGBT people in prison

- LGBT rights by country or territory—including gender identity/expression

- List of transgender-related topics

- List of transgender-rights organizations

- Transgender inequality

- Transgender rights movement

- Transitioning (transgender)

- Yogyakarta Principles

- Human rights

Notes

- Transgender Rights (2006, ISBN 0816643121), edited by Paisley Currah, Richard M. Juang, Shannon Minter

- Thomas E. Bevan, The Psychobiology of Transsexualism and Transgenderism (2014, ISBN 1440831270), page 42: "The term transsexual was introduced by Cauldwell (1949) and popularized by Harry Benjamin (1966) [...]. The term transgender was coined by John Oliven (1965) and popularized by various transgender people who pioneered the concept and practice of transgenderism. It is sometimes said that Virginia Prince (1976) popularized the term, but history shows that many transgender people adovcated the use of this term much more than Prince. The adjective transgendered should not be used [...]. Transsexuals constitute a subset of transgender people."

- A. C. Alegria, Transgender identity and health care: Implications for psychosocial and physical evaluation, in the Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, volume 23, issue 4 (2011), pages 175–182: "Transgender, Umbrella term for persons who do not conform to gender norms in their identity and/or behavior (Meyerowitz, 2002). Transsexual, Subset of transgenderism; persons who feel discordance between natal sex and identity (Meyerowitz, 2002)."

- Valentine, David. Imagining Transgender: An Ethnography of a Category, Duke University, 2007

- Stryker, Susan. Introduction. In Stryker and S. Whittle (Eds.), The Transgender Studies Reader, New York: Routledge, 2006. 1–17

- Kelley Winters, "Gender Madness in American Psychiatry, essays from the struggle for dignity, 2008, p. 198. "Some Transsexual individuals also identify with the broader transgender community; others do not."

- "retrieved 20 August 2015: " Transsexualism is often included within the broader term 'transgender', which is generally considered an umbrella term for people who do not conform to typically accepted gender roles for the sex they were assigned at birth. The term 'transgender' is a word employed by activists to encompass as many groups of gender diverse people as possible. However, many of these groups individually don't identify with the term. Many health clinics and services set up to serve gender variant communities employ the term, however most of the people using these services again don't identify with this term. The rejection of this political category by those that it is designed to cover clearly illustrates the difference between self-identification and categories that are imposed by observers to understand other people."". Gendercentre.org.au. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Duthel, Heinz. Kathoey Ladyboy: Thailand's Got Talent.

- "Japanese Law Translation - [Law text] - Act on Special Cases in Handling Gender Status for Persons with Gender Identity Disorder". Japaneselawtranslation.go.jp. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Gender Recognition Act 2004". Legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Gender Recognition Bill [HL] — 10 Feb 2004 at 18:27". publicwhip.org.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- "Gender Recognition Bill votes". christian.org.uk. 17 March 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- EP (17 March 2007). "Entra en vigor la Ley de Identidad de Género". Sociedad.elpais.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "BBC NEWS - World - Americas - Uruguay approves sex change bill". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Argentina approves gender identity law". Pinknews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Denmark becomes Europe's leading country on legal gender recognition - The European Parliament Intergroup on LGBTI Rights". Lgbt-ep.eu. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "The Gender Identity Act". Timesofmalta.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Decreto 1227 Del 04 de Junio de 2015". Scribd. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Colombia's new gender recognition law doesn't require surgery". Pinknews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "These Ten Trans People Just Got Their First IDs Under Colombia's New Gender Rules". Buzzfeed.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Legal Gender Recognition in Ireland : Gender Recognition : TENI". Teni.ie. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Poselski projekt ustawy o uzgodnieniu płci

- "Vietnam: Positive Step for Transgender Rights". Hrw.org. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Vietnam Passes Transgender Rights Law, But Is It Good Enough? - Care2 Causes". Care2.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Nothing found for 2016 01 29 Change Of Gender In Identity Card Will Require Two Witnesses". Ecuadortimes.net. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Segundo Suplemento – Registro Oficial Nº 684" (PDF). Asambleanacional.gob.ec. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Bolivia proposes law allowing transgender people to officially change names, genders - Shanghai Daily". Shanghaidaily.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- comunicacion, Unidad de. "Presentan anteproyecto de ley para cambiar datos de identidad de las personas transexuales y transgénero". Justicia.gob.bo. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Bolivia: comunidad LGTB presiona a la Asamblea Legislativa para que trate ley de identidad de género - NODAL". Nodal.am. 29 December 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Norway set to allow gender change without medical intervention". Yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Services, Ministry of Health and Care (18 March 2016). "Easier to change legal gender". Government.no. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Lov om endring av juridisk kjønn". Stortinget. 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Dispatches: Norway's Transgender Rights Transformation". Hrw.org. 7 June 2016. Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Rook, Erin (16 October 2016). "France will no longer force the sterilization of transgender people". Lgbtqnation.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "It's official – France adopts a new legal gender recognition procedure! - ILGA-Europe". Ilga-europe.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "LOI n° 2016-1547 du 18 novembre 2016 de modernisation de la justice du XXIe siècle" (PDF). Legifrance.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "PRS - Bill Track - The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2016". Prsindia.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Cabinet approves the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill 2016". pib.nic.in. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Amendment of Transgender Bill: Government Accepts Standing Committee Proposal". The Logical Indian. 17 December 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "C-16 (42-1) - Royal Assent - An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code - Parliament of Canada". Parl.ca. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Pujol-Mazzini, Anna. "Belgium's ban of forced sterilisation for gender change". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Nouvelle loi transgenre: qu'est-ce qui change en 2018?". RTBF Info (in French). 22 December 2017.

- News, ABC. "Controversial Greek gender identity bill in parliament vote". ABC News. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- "Greece passes sex change law opposed by Orthodox Church". Reuters. 10 October 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- Shahid, Jamal (10 February 2018). "Senate body approves changes to transgender persons rights bill". dawn.com. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- Khan, Iftikhar A. (8 March 2018). "Senate adopts bill to protect rights of transgender persons". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Pakistan Enacts Legislation Protecting Transgender People". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Iniciativa". Parlamento.pt. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Rodrigues, Sofia. "BE apresenta projecto de lei para permitir mudança de sexo aos 16 anos". PÚBLICO. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Group, Global Media (25 May 2016). "BE quer permitir mudança de sexo aos 16 anos". Jn.pt. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Lei da autodeterminação da identidade de género entra em vigor amanhã". ionline (in Portuguese). Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Publicada lei que concede direito à autodeterminação de género". Esquerda (in Portuguese). Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Civil status: New law facilitates transgender, intersex name and gender change". Wort.lu. 17 May 2017. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Résumé des travaux du 12 mai 2017 - gouvernement.lu // L'actualité du gouvernement du Luxembourg". Gouvernement.lu. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Proyecto de Ley Integral Trans". parlamento.gub.uy (in Spanish).

- "Uruguay's first transgender senator vows to bolster LGBT rights". Reuters. 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "Boletín 8924-07 Reconoce y da protección al derecho a la identidad de género". Senado.cl. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Acuerdan avanzar en el reconocimiento de la identidad de género". Senado.cl (in Spanish). 21 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- "Senado - República de Chile - A segundo trámite proyecto que reconoce y da protección a la identidad de género". Senado.cl (in Spanish). 14 June 2017. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- "PL 5002/2013 - Projeto estabelece direito à identidade de gênero". Camara.gov.br (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Proyecto de ley 19841". Asamblea.go.cr. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Change In Sex Designation In Identity Card (Cedula) Possible If Bill Is Approved". Qcostarica.com. 19 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "LEY DE RECONOCIMIENTO DE LOS DERECHOS A LA IDENTIDAD DE GÉNERO E IGUALDAD ANTE LA LEY" (PDF). Conasida.go.cr. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "FMLN Backs New Gender Identity Law Defending the Rights of the Transgender Community | CISPES: Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador". Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Vargas, Esther (4 November 2016). "Perú necesita una Ley de Identidad de Género y hoy se hizo algo importante". Sin Etiquetas (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- "El Congreso aprueba reformar la ley de identidad de género y despatologizar la transexualidad con la oposición del PP". dosmanzanas - La web de noticias LGTB (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "Swedish law proposals on legal gender recognition and gender reassignment treatment - ILGA-Europe". Ilga-europe.org. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Egyes közigazgatási tárgyú törvények módosításáról, valamint ingyenes vagyonjuttatásról" (PDF). Országgyűlés (Hungarian National Parliament). Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Hungary passes bill ending legal gender recognition for trans citizens". Euronews. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Hungarian government outlaws legal gender recognition". TGEU (Transgender Europe). Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- De Vos, Pierre (14 July 2010). "Christine, give them hell!". Constitutionally Speaking. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- Alteration of Sex Description and Sex Status Act, 2003 Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Parliament of South Africa, 15 March 2004.

- "Botswana: Activists Celebrate Botswana's Transgender Court Victory". Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Press Release: Botswana High Court Rules in Landmark Gender Identity Case

- “Sweet closure” as Botswana finally agrees to recognise trans man, Mambaonline

- "Botswana to recognise a transgender woman's identity for first time after historic High Court ruling". independent.co.uk. 18 December 2017.

- Jun, Pi (9 October 2010). "Transgender in China". Journal of LGBT Youth. 7 (4): 346–351. doi:10.1080/19361653.2010.512518.

- Sun, Nancy (9 January 2014). "Shanxi Permits Persons to Change Gender Information". All-China Women's Federation. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Winter, Sam; Conway, Lynn. "How many trans* people are there? A 2011 update incorporating new data". Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Chan, Kelvin. "HK Transgender Woman Wins Legal Battle to Marry". ABC News. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "Hong Kong court supports transsexual right to wed". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "Hong Kong customs officers behaved 'like animals' during body search", South China Morning Post, 1 November 2013, archived from the original on 14 February 2014, retrieved 2 February 2014

- Trans woman subjected to invasive search at Hong Kong airport, 1 November 2013, archived from the original on 20 February 2014, retrieved 2 February 2014

- "為換護照慘失國籍失學位失尊嚴 被海關當畜牲 跨性別博士來港 三失不是人 (A want to change her passport costed her nationality, degree and dignity - Treated by customs like an animal - Transgender doctorate student came to Hong Kong and lost everything)", Apple Daily, 1 November 2013, archived from the original on 29 January 2014, retrieved 2 February 2014

- "Transgender refugee goes through 'hell' in Hong Kong to be recognised as a woman", South China Morning Post, 3 April 2014, archived from the original on 16 April 2014, retrieved 16 April 2014

- "India recognises transgender people as third gender". The Guardian. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- McCoy, Terrence (15 April 2014). "India now recognizes transgender citizens as 'third gender'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- "Supreme Court recognizes transgenders as 'third gender'". The Times of India. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- "Why transgender not an option in civil service exam form: HC". Archived from the original on 3 December 2015.

- "Why transgender not an option in civil service exam form: HC". Archived from the original on 25 January 2016.

- National Legal Services Authority ... Petitioner Versus Union of India and others ... Respondents (Supreme Court of India 15 April 2014). Text

- Fathi, Nazila (2 August 2004). "As Repression Lifts, More Iranians Change Their Sex". The New York Times.

- Tait, Robert (27 July 2005). "A Fatwa for Freedom". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- "Human Rights Report: Being Transgender in Iran" (PDF). Outright. Action International. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Barford, Vanessa (25 February 2008). "BBC News: Iran's 'diagnosed transsexuals'". British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- "Iran's transgender people face discrimination despite fatwa". AP NEWS. 21 May 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Human Rights Report: Being Transgender in Iran" (PDF). Outright. Action International. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "The gay people pushed to change their gender". BBC. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Hays, Matthew. "Iran's gay plan". CBC News. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Sex change funding undermines no gays claim", Robert Tait, The Guardian, 26 September 2007; accessed 20 September 2008.

- "Waseda Bulletin of Comparative Law" (PDF). Waseda.jp. p. 42. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- 性同一性障害者の性別の取扱いの特例に関する法律 Archived 22 July 2012 at Archive.today e-Gov – Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan (in Japanese)

- Act on Special Cases in Handling Gender for People with Gender Identity Disorder Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Japanese Law Translation – Ministry of Justice, Japan

- "Transsexual's 'Change' Recognized". Tokyo: CBS News. 29 July 2004. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Japan to fund gender-affirming surgery". Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "Japan's Supreme Court rules transgender people still have to get sterilised". Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- "JeffreyJessie: Recognising Transsexuals" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Malaysian Bar. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- "J.G v. Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara". Cljlaw.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Archived 18 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Jon Boone in Islamabad. "Pakistan's chief justice Iftikhar Chaudhry suffers public backlash | World news". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Awareness about sexually transmitted infections among Hijra sex workers of Rawalpindi/Islamabad" (PDF). Pakistan Journal of Public Health. 2012.

- "A Second Look at Pakistan's Third Gender". Positive Impact Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "القضاء يوافق على تغيير جنس أردني من ذكر إلى أنثى". وكالة عمون الاخبارية. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- "newsinfo.inquirer.net, Call him Jeff, says SC; he used to be called Jennifer". Newsinfo.inquirer.net. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Rare Condition Turns Woman Into Man". Fox News. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "Sex change and sex reassignment - Katrina Legarda - ABS-CBN News". Web.archive.org. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Un, Ji-Won; Park, Hyun-Jung (16 May 2013). "Landmark legal ruling for South Korean transgenders". The Hankyoreh. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Ministry of Interior Affairs, R.O.C. (Taiwan) (3 November 2008). "有關戶政機關受理性別變更登記之認定要件" [Regarding the assessment criteria for household registration authorities to accept gender change registration]. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- 洪, 滋敏 (16 February 2016). "醫療進步的台灣也有變性需求,但提到動手術為何會先想到泰國?" [Medically-advanced Taiwan has demand for sex change, but why do people think of Thailand instead?]. The News Lens. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Department of Household Registration, Ministry of Interior Affairs, R.O.C. (Taiwan). "性別變更認定及登記程序相關資訊" [Related information on the assessment and registration procedure of gender change]. Retrieved 13 June 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- 潘, 姿羽 (21 November 2018). "2020年啟用晶片身分證 保留數字7給跨性別人士" [Chip-embedded ID to release in 2020, digit 7 reserved for transgender persons]. Central News Agency, Taiwan. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "聯名新聞稿/性別團體回應國發會新制身分證意見" [Joint press release/ gender groups' response to the National Development Council on the new identity card]. Beyond Gender (Intersex, Transgender and Transsexual People Care Association). 23 November 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Wareham, Jamie (29 August 2017). "Finland will keep sterilizing trans people after it rejects law reform". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "Transgender people win major victory in France". Gaystarnews.com. 13 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "A row over transgender rights erupts between Greece's politicians and its clerics". The Economist. 13 October 2017. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017.

- "Greece improves gender recognition law but misses chance to introduce self-determination". ILGA EUROPE. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- "Greece passes gender-change law opposed by Orthodox church". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- "Ελλάδα: Εφαρμόστηκε η δικαστική απόφαση για ληξιαρχική μεταβολή φύλου χωρίς το προαπαιτούμενο χειρουργικής επέμβασης". Antivirus Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "Έλληνας τρανς άντρας αλλάζει στοιχεία χωρίς χειρουργική επέμβαση (Greek trans man changes information without sex reassignment surgery". 10percent. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "Dr Lydia Foy's Case". Transgender Equality Network Ireland. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ""Ireland passes bill allowing gender marker changes on legal documents". Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Gender Recognition Certificate". Department of Social Protection. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- "Ireland passes law allowing trans people to choose their legal gender". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- "Anna Grodzka" (in Polish). SEJM. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- see for example: T. Smyczynski, Prawo rodzinne i opiekuńcze, C.H. Beck 2005

- "Wybory 2011: Andrzej Duda (PIS) zdeklasował konkurentów w Krakowie" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Hudson, David (30 May 2013). "Anna Grodzka: what's it like being the world's only transsexual MP?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ""I'm not giving up": Poland's first transgender MP Anna Grodzka on her activism". www.newstatesman.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- Lei n.º 38/2018

- "Transsexualismul in Romania". Accept Romania. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- "Transgender: what the law says". equalityhumanrights.com. Equality and Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- "Equality Act 2010". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 2010. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- "Applying for a Gender Recognition Certificate". Gov.uk. The UK Government. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- "LEGISinfo". Parl.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "LEGISinfo - House Government Bill C-16 (42-1)". Parl.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Tasker, John Paul (16 June 2017). "Canada enacts protections for transgender community". CBC News. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- "Mexico: Mexico City Amends Civil Code to Include Transgender Rights", International Gay & Lesbian Human Rights Commission, 15 June 2004

- "The Violations of the Rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Persons in Mexico: A Shadow Report", submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Committee by The International Human Rights Clinic, Human Rights Program of Harvard Law School; Global Rights; and the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, March 2010, footnote 77, page 13 Archived 31 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Mexico City Approves Easier Transgender Name Changes Archived 10 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Aprueban reforma a la ley de identidad de género en la Ciudad de México Archived 28 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Aprueban Ley de Identidad de Género en Michoacán Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Aprueba Congreso de Nayarit ley de identidad de género

- "Gender Designation Change", Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State Archived 2 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Funk, Jaydi; Funk, Steven; Whelan, Sylvia Blaise (2019). "Trans*+ and Intersex Representation and Pathologization: An Interdisciplinary Argument for Increased Medical Privacy". Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law & Justice. 34 (1). doi:10.15779/z380c4sk4f.

- Anushka Patil (15 June 2020). "How a March for Black Trans Lives Became a Huge Event". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Shannon Keating (6 June 2020). "Corporate Pride Events Can't Happen This Year. Let's Keep It That Way". Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Latin America's Transgender-Rights Leaders". The New Yorker. 10 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016.

- "Bolivia's transgender citizens celebrate new documents". BBC News. 7 September 2016. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016.

- "Argentina Gender Identity Law - TGEU - transgender europe". Web.archive.org. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Bolivia Approves Progressive Law Recognizing Transgender Rights". Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "En un mes 50 transgénero y transexuales cambiaron su identidad en Bolivia" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- Transgenders can change their name, as decided by the Supreme Court of Justice (in Portuguese) Archived 10 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Sex-change in Brazil (in Portuguese) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Brazil to provide free sex-change operations (in English) Archived 24 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Chile transgender rights law takes effect". Washington Blade: Gay News, Politics, LGBT Rights. 30 December 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "Ecuadorean Lawmakers Approve New Gender Identity Law". Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "LEY ORGÁNICA DE GESTIÓN DE LA IDENTIDAD Y DATOS CIVILES" (PDF). Asambleanacional.gob.ec (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "Reniec en desacuerdo con cambio de sexo en DNI, pese a orden de Juzgado en Arequipa". Peru21 (in Spanish). 31 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "Trans people in Uruguay can now self-identify their gender, without surgery". Gay Star News. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "Ley 18.620 DERECHO A LA IDENTIDAD DE GÉNERO Y AL CAMBIO DE NOMBRE Y SEXO EN DOCUMENTOS IDENTIFICATORIOS". legislativo.parlamento.gub.uy (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "BIRTHS, DEATHS AND MARRIAGES REGISTRATION ACT 1995 - SECT 32B Application to alter register to record change of sex". 5.austlii.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "NSW Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages v Norrie [2014] HCA 11 (2 April 2014)". High Court of Australia. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Sex and Gender Diverse Passport Applicants". Passports.gov.au. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Cohen, Janine (15 August 2016). "Transgender teenagers 'risking lives' buying hormones on black market". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- Lane Sainty (30 November 2017). "Transgender Teens Can Now Access Treatment Without Going To Court, Following Landmark Decision". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017.

- CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI Archived 6 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "President signs long-awaited Fiji constitution into law". ABC News. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Guam Archived 15 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine National Center for Transgender Equality

- Human Rights Act 1993 s21(1)(m)

- Human Rights Commission: “Human Rights in New Zealand Today – New Zealand Action Plan for Human Rights. August 2004. P.92

- "Vital Statistics Act of 2006". Public Law No. 15-50 of 2006 (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Sentencing Act 2016 Archived 29 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Chow, Melinda. (2005). "Smith v. City of Salem: Transgendered Jurisprudence and an Expanding Meaning of Sex Discrimination under Title VII". Harvard Journal of Law & Gender. Vol. 28. Winter. 207.

- Currah, Paisley; Juang, Richard M.; Minter, Shannon Price, eds. (2006). Transgender Rights. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- Sellers, Mitchell D. (2011). "Discrimination and the Transgender Population: A Description of Local Government Policies that Protect Gender Identity or Expression". Paper 360. Applied Research Projects, Texas State University-San Marcos. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Hoston, William (14 June 2018). Toxic Silence. Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 9781433155994.