Marlboro Township, New Jersey

Marlboro Township is a township in Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2010 United States Census, the township had a population of 40,191,[9][10][11] reflecting an increase of 5,449 (+16.3%) from the 33,423 counted in the 2000 Census, which had in turn increased by 6,707 (+25.1%) from the 26,716 counted in the 1990 Census.[20]

Marlboro Township, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

| Township of Marlboro | |

Seal | |

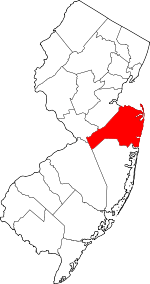

Map of Marlboro Township in Monmouth County. Inset: Location of Monmouth County highlighted in the State of New Jersey. | |

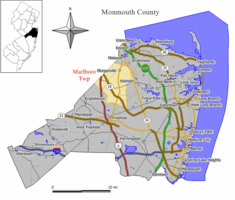

Census Bureau map of Marlboro Township, New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 40.342931°N 74.257197°W[1][2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Monmouth |

| Incorporated | February 17, 1848 |

| Named for | Marl beds |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (mayor–council) |

| • Body | Township Council |

| • Mayor | Jonathan L. Hornik (D, term ends December 31, 2023)[4][5] |

| • Administrator | Jonathan Capp[6] |

| • Municipal clerk | Alida Manco[7] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 30.471 sq mi (78.921 km2) |

| • Land | 30.361 sq mi (78.636 km2) |

| • Water | 0.110 sq mi (0.285 km2) 0.36% |

| Area rank | 89th of 566 in state 9th of 53 in county[1] |

| Elevation | 190 ft (60 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 40,191 |

| • Estimate (2019)[12] | 39,640 |

| • Rank | 53rd of 566 in state 3rd of 53 in county[13] |

| • Density | 1,323.7/sq mi (511.1/km2) |

| • Density rank | 352nd of 566 in state 42nd of 53 in county[13] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | |

| Area code(s) | 732/848[16] |

| FIPS code | 3402544070[1][17][18] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0882118[1][19] |

| Website | www |

Marlboro Township was formed by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on February 17, 1848, from portions of Freehold Township.[21] The township was named for the marl beds found in the area.[22]

History

Historical timeline

Lenni Lenape

While there is some debate on this, the Lenni Lenape Native Americans were the first known organized inhabitants of this area, having settled here about one thousand years ago and forming an agricultural society, occupying small villages that dotted what was to become Marlboro Township.[23] Their villages were known to be in the Wickatunk and Crawford's Corner sections of the township.[24][25]

In 1600, the Delaware / Lenape Native American population in the surrounding area may have numbered as many as 20,000.[26][27] Several wars, at least 14 separate epidemics (yellow fever, small pox, influenza, encephalitis lethargica, etc.) and disastrous over-harvesting of the animal populations reduced their population to around 4,000 by the year 1700. Since the Lenape people, like all Native Americans, had no immunity to European diseases, when the populations contacted the epidemics, they frequently proved fatal.[28] Some Lenape starved to death as a result of animal over-harvesting, while others were forced to trade their land for goods such as clothing and food. They were eventually moved to reservations set up by the US Government. They were first moved to the only Indian Reservation in New Jersey, the Brotherton Reservation in Burlington County, New Jersey (1758-1802).[29] Those who remained survived through attempting to adapt to the dominant culture, becoming farmers and tradesmen.[30] As the Lenni Lenape population declined, and the European population increased, the history of the area was increasingly defined by the new European inhabitants and the Lenape Native American tribes played an increasingly secondary role.

Dutch arrival

Within a period of 112 years, 1497–1609, four European explorers claimed this land for their sponsors: John Cabot, 1497, for England; Giovanni de Verrazano, 1524, for France; Estevan Gomez, 1525, for Spain, Henry Hudson, 1609, for Holland. After the Dutch arrival to the region in the 1620s, the Lenape were successful in restricting Dutch settlement to Pavonia in present-day Jersey City along the Hudson River until the 1660s and the Swedish settlement to New Sweden (1655 - The Dutch defeat the Swedes on the Delaware). The Dutch established a garrison at Bergen allowing settlement of areas within the province of New Netherland. For 50 years, 1614–1664, the Monmouth County area came under the influence of the Dutch, but it was not settled until after English rule in 1664.

The initial European proprietors of the area purchased the land from the Lenni Lenape leader or Sakamaker.[31] The chief of the Unami, or Turtle clan, was traditionally the great chief of all the Lenni Lenape. One of the sons of the leader, was Weequehela[32] who negotiated the sale of several of the initial tracts of land to the first farmers.[33] An early deed refers to "the chief sachems or leaders of Toponemus."

On April 2, 1664, the English appointed Richard Nicolls to serve as the Deputy Governor of New York and New Jersey. One year later, April 8, 1665, Nicolls issued "The Monmouth Patent" to twelve men who had come from Western Long Island and New England seeking permanent stability for religious and civil freedom as well as the prospect of improving their estates. Nicolls was unaware that in June, 1664, James had given a lease and release for New Jersey to Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, thus invalidating the grant to the Monmouth Patentees.[25] The rule at the time was that land should be purchased from the Patent.

However, in the time between 1685 and the early 18th century, the patent was ignored and land was gradually purchased from the Lenni Lenape causing confusion and disputes over ownership. Following the initial sale of land, the history of the township starts about 1685, when the land was first settled by European farmers from Scotland, England and the Netherlands. The Scottish exiles[34] and early Dutch settlers lived on isolated clearings carved out of the forest.[35] The lingua franca or common language spoken in the area was likely, overwhelmingly Dutch. However, this was one of many languages spoken with the culture very steeped in New Netherlander. The official documentation at the time is frequently found to be in the Dutch language. The documents of the time also suggest that money transactions used the British shilling.[36] The English and Scotch settlers were Quakers. After initial European contact, the Lenape population sharply declined.

The first settlers of the area were led by missionary George Keith. They were Quakers. The Quakers established a town called "Topanemus" and nearby a meetinghouse and a cemetery on what is now Topanemus Road[37] and held the first meeting on October 10, 1702.[38] The first leader of the church was Rev. George Keith who received a large grant of land[39] in the area due to his position as Surveyor-General.[40] Among the first listed communicants of the new church were Garret and Jan Schenck.[41] The church later changed its affiliation to the Episcopal faith and became St. Peter's Episcopal Church which is now located in Freehold.[42] The old burial ground still remains on Topanemus Road. In 1692 those of the Presbyterian Faith built a church and burial ground on what is now Gordons Corner Road. The church eventually moved to Tennent where it became known as the Old Tennent Church and played a role in the American Revolutionary War. The old Scots Cemetery still remains at its original site.

Marl's discovery

The township of Marlboro is named for the prevalence of marl,[43] which was first discovered in the area east of the village in 1768. Marl was used extensively on farms and spread during the winter months to be tilled into the soil in the spring.[44] The "Marl Pits" are clearly reflected on maps from 1889 shown as a dirt road off of Hudson Street heading towards the current location of the township soccer fields.[45] Farmers used marl to improve the soil in the days before commercial fertilizers and there was a heavy demand for it. Marlboro Township's first industry was the export of the material, used primarily as fertilizer. In 1853, the Marl was harvested and transported to other parts of the state and to the Keyport docks via the Freehold Marl Company Railroad (now the Henry Hudson Trail).[46][47] The marl was then sent to New York and other parts of the country via ship.[48] Prior to the finding of Marl, the area was known as 'Bucktown' for John Buck who owned a tavern in the area.[49]

Revolutionary War

Marlboro Township was the scene of a number of skirmishes during the American Revolutionary War, in particular following the Battle of Monmouth in 1778. During the war, the Pleasant Valley section was often raided by the British for food supplies and livestock.[48] The area was referred to as the "Hornet's Nest" because of the intensity of attacks on the British by local militia.[50] Beacon Hill (of present-day Beacon Hill Road) was one of three Monmouth County sites where beacons were placed to warn the residents and the Continental forces if the enemy should approach from the bay.[51][52] There was also considerable activity in the Montrose area of the Township as British troops, retreating from the Battle of Monmouth, tried to wind their way to ships lying off Sandy Hook.[53]

The area was also frequently sacked for food and livestock. The woods and surrounding vegetation were hunted for animals to depletion by the British. One description of a hunt was recorded: "A great deer-drive was organized, taking in almost the entire northern portion of Monmouth county. Before daylight... a line of men... was stretched... somewhere near Marlboro. At an appointed hour this line of beaters, with shot and shout... proceeded forward to drive as large as possible a number of deer to the shore between Port Monmouth and Atlantic Highlands. The drive was completely successful... that deer were almost exterminated in the northerly part of the county."[54]

Township formation

Under the direction and influence of John W. Herbert,[55] Marlboro was established as a township by an act of the New Jersey Legislature on February 17, 1848, formed from portions of Freehold Township.[21] The township's name was originally "Marlborough," but was subsequently changed to "Marlboro."[56] It is unknown when the name was officially changed, with maps and other documents in the decades after the township's establishment referring variously to "Marlboro"[57] or "Marlborough".[58][59] The first elected freeholder was John W. Herbert.

Marlboro was rural and composed mostly of dairy farms, potato, tomato and other farms laced with small hamlets with modest inns or taverns.[60] Before World War II Marlboro Township was actually the nation's largest grower of potatoes and also known for a large tomato and egg industry.[61] During World War II, egg farms significantly expanded to accommodate military demand.

Following World War II, the state began to significantly build and improve the area transportation infrastructure. As the infrastructure improved, the population started to increase. The 50s and 60s saw Marlboro starting to significantly grow. Housing developments started to replace the farm and rural nature as the community expanded. After the early 1970s, Marlboro became a growing suburb for people working in New York and in large nearby corporations. During the 1980s and early 1990s most of the new housing developments featured four- or five-bedroom houses, but later the trend shifted toward larger estate homes. The building effort became so advanced that Marlboro Township placed restrictions for building around wetlands; called the Stream Corridor Preservation Restrictions to mitigate construction and habitat contamination.

The year 2000 saw continued growth of the housing trend toward larger homes. Towards the end of the decade, housing growth declined due to the Great Recession.

Historical events

Town center

The Marlboro township center has historically been considered an area around the intersection of Main Street (Route 79) and School Road.[62] In the late 19th century the intersection held two hotels (both of them are now gone), general store (was on the lot of the current fire department building), and Post Office (was on the lot of a current Chinese Restaurant). Behind the current small mini-mart on the corner of this intersection, you can still see one of the original barns from the early 19th century. However, Marlboro no longer has any official town center and can be considered an example of suburban sprawl. Efforts are underway to create an official "Village Center" and multiple proposals have come forward in recent discussions.[63] Current vision statements suggest the creation of a pedestrian-friendly, mixed use Village Center, with an emphasis on walkability and traffic calming.[64]

Cell phone ban

In 2000, Marlboro became the first municipality in New Jersey, and one of the first areas in the U.S., to ban cell phone use while driving, a ban that took effect in March 2001. The restriction established made use of a cell phone a primary offense, allowing a police officer to stop a motorist for phone use.[65]

Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital

Opened in 1931, Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital was located on 400 acres (1.6 km2) in the eastern part of the township. It was opened with much fanfare as a "state of the art" psychiatric facility. It was closed 67 years later on June 30, 1998, as part of a three-year deinstitutionalization plan in which some the state's largest facilities were being shut down, with Marlboro's 800 patients being shifted to smaller facilities and group homes.[66][67] The land that the hospital was placed on was known as the "Big Woods Settlement". It was largely farm land but there was a large distillery on the property which was torn down to make room for the hospital.[57] Additionally, due to the long residential stays at the hospital, a cemetery was also located near the hospital for the residents who died while in residence and were unclaimed. There is currently a large fence around the hospital and the hospital was completely demolished in 2015. Most of the land was handed over to the Monmouth County Park system and some of the ground will be the final linkage of the Henry Hudson Trail. The park system had developed the Big Brook Park and continues to expand and work on the park to provide services to the Monmouth County residents.

40% Green

In June 2009, Marlboro Township Municipal Utilities Authority (MTMUA) deployed a 900 kW solar power array from Sharp that will enable the MTMUA to meet nearly 40% of its electricity needs with emissions-free solar-generated power. This is considered one of the largest of its kind in the East. This solar energy system will reduce New Jersey CO2 emissions by more than 4,200,000 lb (1,900,000 kg) annually; SO2 emissions by 28,000 lb (13,000 kg); and NO2 emissions by 18,000 lb (8,200 kg)., as well as eliminating significant amounts of mercury.[68] Additionally, Marlboro has been recognized as a Cool City by the Sierra Club. Marlboro is the 10th Monmouth County municipality to be named a Cool City.[69]

Preston Airfield

Marlboro had an airport, Preston Airfield, which opened in 1954 and was in operation for almost 50 years. The airport was opened by Rhea Preston on his farm and consisted of two runways, one was 2,400 feet (730 m) as well as airplane hangars. It obtained a paved runway before 1972. In 1974, the airport had approximately 100 planes, 8 of which are used for air instruction.[70] It won many awards and in 1974 was cited by the state Aviation Advisory Council as the "best maintained" airport.[71] In 1975, the airport was given Planning Board approval to expand with 21 additional hangars and add an 840 square foot operations building.[72] Exact records are not known as to when it changed its name to Marlboro Airport. The Garden State Art Center was known to have used the airport to fly in entertainers such as Jimmy Buffett, Jon Bon Jovi, and Howard Stern for performances.[73] Planning board records reflect the intention to make this change in 1976.[72] The NJ department of Transportation provided $4.8 million to expand Preston Airport.[74] In 1979, the airport was described as having a single runway 2,200 feet (670 m) long. The airport was used for private aviation (Fixed wing as well as helicopters)[75] as well as having a private school for flying instruction.[76] In 2000, the airport was purchased by Marlboro Holdings LLC owned by Anthony Spalliero who closed it with the intent to redevelop the airport into housing.[77] To foster the case for redevelopment, Spalliero donated land holdings he had near the airport to the township Board of Education, which was used to develop the Marlboro Early Learning Center, a school specialized for kindergarten classes. Following a $100,000 pay-off[78] to former Mayor Matthew Scannapieco the planning board used the distance to the new school as justification to close the airfield[79] citing a reference to a fatal plane crash in 1997.[80] Part of the airport has now been developed into Marlboro Memorial Cemetery which now borders the defunct airfield.[81] The other part of the airfield has been absorbed into the Monmouth County Park System.

Virgin Mary sighting

Starting in 1989, Joseph Januszkiewicz started reporting visions of the Virgin Mary near the blue spruce trees in his yard.[82] The visions started to appear six months after he returned from a pilgrimage to Međugorje in Yugoslavia. Since that time as many as 8,000 pilgrims have gathered on the first Sundays of June, July, August and September to pray, meditate and share in the vision.[83] On September 7, 1992, Bishop John C. Reiss gave Januszkiewicz permission to release his messages. In 1993, the Catholic Diocese of Trenton ruled that nothing "truly miraculous" was happening at the Januszkiewicz home. Pictures were taken in November 2004 of a paranormal mist that showed up at the location of the vision, though by April 2005, Januszkiewicz claimed that the visions had stopped and he reports there have been no sightings since.[84]

Train crash

On October 13, 1919, a Central Railroad train collided with a truck on the Hudson Street crossing. The truck was owned by Silvers Company. The train suffered a derailment but the accident only had one loss of life. Michael Mooney, train engineer, died from burns from the train boiler water.[85][86]

Historic sites

Marlboro Township has a number of historically significant sites. These were identified by the Marlboro Township Historic Commission, Monmouth County Historical Association, Monmouth County Park System and other entities. The township of Marlboro has erected signs in front of some of the historically significant buildings to explain their historical significant status. Multiple signs can be seen along Main Street and on some other streets in the town center area.

The Marlboro Township Historic Commission was set up to assist in preserving and publicizing the township's history. It recommends programs and policies to the Mayor and the Township Council on issues of historic significance. It provides homeowners with information on historic preservation and renovation. The Commission also maintains signs in Marlboro Township of some of the historically significant locations. The Historic Commission is composed of nine members, appointed by the Mayor for three year terms, who volunteer their time without receiving any compensation.[87]

Geography

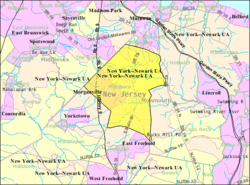

According to the United States Census Bureau, the township has a total area of 30.471 square miles (78.921 km2), including 30.361 square miles (78.636 km2) of land and 0.110 square miles (0.285 km2) of water (0.36%).[1][2] The New Jersey Geological Survey map suggests the land is mostly made up of cretaceous soil consisting of sand, silt and clay.[88]

Morganville (2010 Census population of 5,040[89]) and Robertsville (2010 population of 11,297[90]) are census-designated places and unincorporated communities located within Marlboro Township.[91][92] Other unincorporated communities, localities and place names located partially or completely within the township include Beacon Hill, Bradevelt, Claytons Corner, Henningers Mills, Herberts Corner, Hillsdale, Marlboro (also known as Marlboro Village), Monmouth Heights, Montrose, Mount Pleasant, Pleasant Valley, Smocks Corner, Spring Valley and Wickatunk.[93]

The township borders Aberdeen Township, Colts Neck Township, Freehold Township, Holmdel Township, Manalapan Township and Matawan in Monmouth County; and Old Bridge Township in Middlesex County.[94][95][96]

Weather

Marlboro Township is located close to the Atlantic Ocean. Due to the Marlboro Township's location on the Eastern Seaboard, the following weather features are noted:[97]

- On average, the warmest month is July where the average high is 85 °F (29 °C) and the average low is 66 °F (19 °C).

- The highest recorded temperature was 106 °F (41 °C) in 1936.

- On average, the coolest month is January reaching an average low of 22 °F (−6 °C) and an average high of 40 °F (4 °C).

- The lowest recorded temperature was −20 °F (−29 °C) in 1934.

- The most precipitation on average occurs in July with an average 5.03 inches (128 mm) of rain.

- The least precipitation on average occurs in February with an average of 3.08 inches (78 mm) of rain.

- The average annual precipitation is 46.98 inches (1,193 mm).[98]

- The average number of freezing days is 179.[99]

- The average snowfall (in inches) is 23.2.[100]

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification, Marlboro Township is considered to be in the Cfa zone. Marlboro Township has a humid sub-tropical climate placing it in Zone 7B on the USDA hardiness scale. This extends from Monmouth County, NJ to Northern Georgia. Because of its sheltered location and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, some Palm trees can survive with minimal winter protection. Also, many Southern Magnolias, Crepe Myrtles, Musa Basjoo (Hardy Japanese Banana plants), native bamboo, native opuntia cactus, and bald cypress can be seen throughout commercial and private landscapes.

Tornado

On October 16, 1925, Marlboro Township experienced a tornado. It was reported to be less than a mile wide in destruction. "Large trees were uprooted, small buildings overturned and telephone poles went down".[101]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 1,564 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,083 | 33.2% | |

| 1870 | 2,231 | 7.1% | |

| 1880 | 2,193 | −1.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,913 | −12.8% | |

| 1900 | 1,747 | −8.7% | |

| 1910 | 1,754 | 0.4% | |

| 1920 | 1,710 | −2.5% | |

| 1930 | 1,992 | 16.5% | |

| 1940 | 5,015 | 151.8% | |

| 1950 | 6,359 | 26.8% | |

| 1960 | 8,038 | 26.4% | |

| 1970 | 12,273 | 52.7% | |

| 1980 | 17,560 | 43.1% | |

| 1990 | 27,974 | 59.3% | |

| 2000 | 36,398 | 30.1% | |

| 2010 | 40,191 | 10.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 39,640 | [12][102][103] | −1.4% |

| Population sources: 1850-1920[104] 1850-1870[58] 1850[105] 1870[106] 1880-1890[107] 1890-1910[108] 1910–1930[109] 1900–1990[110] 2000[111][112] 2010[9][10][11] | |||

Marlboro has experienced steady growth since 1940, with the largest population swell occurred during the 1960s and 1970s and a noticeable increase of 10,414 people from 1980–1990. The pace of the growth has slowed in the last decade.[64]

2010 Census

The 2010 United States Census counted 40,191 people, 13,001 households, and 11,193.861 families in the township. The population density was 1,323.7 per square mile (511.1/km2). There were 13,436 housing units at an average density of 442.5 per square mile (170.9/km2). The racial makeup was 78.59% (31,587) White, 2.09% (841) Black or African American, 0.06% (25) Native American, 17.27% (6,939) Asian, 0.00% (2) Pacific Islander, 0.64% (257) from other races, and 1.34% (540) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.03% (1,619) of the population.[9]

Of the 13,001 households, 46.6% had children under the age of 18; 77.8% were married couples living together; 6.1% had a female householder with no husband present and 13.9% were non-families. Of all households, 12.0% were made up of individuals and 6.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.09 and the average family size was 3.38.[9]

28.8% of the population were under the age of 18, 6.3% from 18 to 24, 21.0% from 25 to 44, 32.6% from 45 to 64, and 11.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41.7 years. For every 100 females, the population had 95.8 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 92.7 males.[9]

The Census Bureau's 2006-2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $130,400 (with a margin of error of +/- $6,434) and the median family income was $145,302 (+/- $7,377). Males had a median income of $101,877 (+/- $3,707) versus $66,115 (+/- $5,292) for females. The per capita income for the township was $50,480 (+/- $2,265). About 1.2% of families and 1.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.7% of those under age 18 and 2.2% of those age 65 or over.[113]

2000 Census

As of the 2000 United States Census[17] there were 36,398 people, 11,478 households, and 10,169 families residing in the township. The population density was 1,189.7 people per square mile (459.4/km2). There were 11,896 housing units at an average density of 388.8 inhabitants/mi2 (150.1 inhabitants/km2). The racial makeup of the township was 83.76% White, 2.07% African American, 0.05% Native American, 12.67% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.47% from other races, and 0.97% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.89% of the population.[111][112]

There were 11,478 households, out of which 50.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them. 81.3% were married couples living together, 5.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 11.4% were non-families. 9.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.15 and the average family size was 3.38.[111][112]

In the township the population was spread out, with 30.2% under the age of 18, 5.6% from 18 to 24, 28.8% from 25 to 44, 26.6% from 45 to 64, and 8.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. There are slightly more females than males in the township for both total and adult categories. The census shows that for every 100 females in the township, there were 98.4 males; for every 100 females over 18, there were 94.3 males.[111][112]

The median income for a household in the township was $101,322, and the median income for a family was $107,894. Males had a median income of $76,776 versus $41,298 for females. The per capita income for the township was $38,635. About 2.4% of families and 3.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.4% of those under age 18 and 2.7% of those age 65 or over.[111][112]

Crime

The number of violent crimes recorded by the FBI in 2003 was 15. The number of murders and homicides was 5. The violent crime rate was reported to be very low, at 0.4 per 1,000 people.[114]

Housing

Housing costs

The median home cost in Marlboro Township was $446,890. Home prices decreased by 8.18% in 2010. Compared to the rest of the country, Marlboro Township's cost of living is 57% higher than the U.S. average.[115]

Affordable housing

As part of its obligation under the Mount Laurel doctrine, the Council on Affordable Housing requires Marlboro Township to provide 1,673 low / moderate income housing units.[116] The first two rounds of New Jersey's affordable housing regulations ran from 1987 to 1999. Under a Regional Contribution Agreement (RCA), Marlboro Township signed an agreement in June 2008 that would have Trenton build or rehabilitate 332 housing units, with Marlboro Township paying $25,000 per unit, a total of $8.3 million to Trenton for taking on the responsibility for these units.[117] Under proposed legislation, municipalities may lose the ability to use these RCAs to pay other communities to accept their New Jersey COAH fair housing obligations, which would mean that Marlboro Township is now required to build the balance of housing. When the New Jersey Council on Affordable Housing requested plans to complete this obligation, Marlboro generated the largest number of objectors to an affordable housing plan in the history of New Jersey.[116] Numerous appeals followed and in October 2010, the Appellate Division struck down portions of the 2007 regulations, invalidated the growth share methodology and directed COAH to develop new regulations. The NJ supreme court granted all petitions for certification in October 2010 and is set to hear the appeals. In June 2011, the Governor issued a reorganization plan which eliminated the 12-member COAH, though state courts overturned the governor's plan.[64]

Retirement communities

Marlboro Township has a number of retirement communities, which include:

- The Royal Pines at Marlboro

- The Sunrise Senior Community

- Greenbriar North Senior Housing Development. This development contains over 750 homes.

- Marlboro Greens - This community was built between 1986 and 1988 contains 341 homes.

- Rosemont Estates - Built by Regal Homes, Rosemont Estates offers 242 single-family homes in nine different models and range in size from approximately 2,400 to 2,800 square feet.[118]

- The Chelsea Square in Marlboro - for adults aged 55 and better consists of 225 condos. Chelsea Square includes a clubhouse, walking and biking trails, and a full-time activities director.[119]

Parks and recreation

Marlboro has a township-sponsored recreation program, with activities for all ages including active soccer and basketball[120] leagues for boys and girls; in addition Little League baseball / softball and Pop Warner football / cheerleading, and a growing amateur wrestling program.

In the summer, the Township holds free outdoor concerts by notable popular music artists. In recent years performers have included Jay and the Americans, Bill Haley's Comets, Lesley Gore, Little Anthony & The Imperials, Johnny Maestro & the Brooklyn Bridge, The Platters, The Trammps, and The Tokens.

In 2007, Marlboro introduced monthly indoor concerts at the recreation center. These shows feature many upcoming artists as well as local talent. Artists have included Marlboro's own Bedlight for Blue Eyes and Sound the Alarm.

Marlboro is also home to the Marlboro Players, a private theater group that holds open auditions for background roles. Formed in 1975, the group presented its first performance, Don't Drink the Water, in the following spring.[121]

For walkers and bicyclists, two segments of the Henry Hudson Trail have substantial stretches within the township.[122]

General parks

The Recreation Commission maintains several parks and facilities for public use. However, some ball fields require permits for usage. The following is a list of recreation facilities:

| Park Name | Soccer | Hockey | Tennis | Handball | Tot-Lot | Basketball | Ball Field | Sitting Area | Open Field | Notes | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marlboro Country Park | Swim Club – Membership Required | Link | |||||||||

| Hawkins Road Park | Link | ||||||||||

| Falson Park | Walking Path Available | Link | |||||||||

| Wicker Place Park | Link | ||||||||||

| Marlin Estates Park | Link | ||||||||||

| Nolan Road Park | Tennis court is out of service and blocked off | Link | |||||||||

| Municipal Complex | Shuffle Board, Walking Path, and shelter building | Link | |||||||||

| Defino Central School | |||||||||||

| Robertsville School | |||||||||||

| Recreation Way Park | Link | ||||||||||

| Union Hill Recreation Complex | Walking Paths | Link | |||||||||

| Vanderburg Sports Complex | Aquatic Center – Membership Required | Link | |||||||||

| Brandigon Trail[124] | Part of Henry Hudson Trail – about 20.27 Acres[125] | Link | |||||||||

| Big Brook Park[126] | A major site for fossils from the Cretaceous and Pleistocene ages[127] See contaminated sites and hunting below | Link |

Dog parks

Marlboro has an off-leash dog park located at the township municipal complex off Wyncrest Road, located on Recreation Way.[128]

Fossil collecting

Open to the public, Big Brook transects the border of Colts Neck and Marlboro, New Jersey. The stream cuts through sediments that were deposited during the Late Cretaceous period. Reportedly, prolific finds of fossils, such as shark teeth, and other deposits of Cretaceous marine fossils, including belemnites are frequently found.[129] This is a particularly fossiliferous site, with finds including fish teeth, crab and crustacean claws, shark teeth, rarely dinosaur teeth, dinosaur bone fragments (and on a very rare occasion a complete bone), megalodonyx (prehistoric sloth) teeth and bone fragments.[130] The area is regarded as one of the top three dinosaur fossil sites in the state. Multiple dinosaur finds have been found in this area.[131] In 2009, a leg section from a duckbilled dinosaur called a hadrosaur was found.[132][133] The first dinosaur discovery in North America was made in 1858 in this area.[134] Several bones from a Mastodon were found in 2009 by an individual fossil hunting.[135] The deposits of marl which gave the township its name have played a major role in preserving the fossils found in the area.[136] The fossil beds can be accessed from the bridge on Monmouth Road in Marlboro.[137]

Bow hunting

Some areas of Monmouth County Big Brook Park allow bow hunting access with a permit.[138]

Golf

Bella Vista Country Club has an 18-hole course over 5,923 yards with a par of 70. It is considered a Private Non-Equity club.[139]

Walking/jogging trail

The Henry Hudson Trail goes through parts of Marlboro. In September 2009, the Monmouth County Park System closed a section of the Henry Hudson Trail Southern Extension going through Marlboro Township (Aberdeen Township to Freehold) for 18 months while a portion of the path that runs through the Imperial Oil superfund clean-up site was remediated.[140]

Festivals

- Music Festival - Spring

- Dinosaur Day - April

- Memorial Day Parade - May

- Marlboro Stomp The Monster 5k & Festival - May

- Marlboro Blues & BBQ Festival - Fall

- Marlboro Day - Summer/Fall

- Halloween Party & Parade - October

- Multicultural Day - November

Summer camps

Marlboro Township offers a summer camp program for grade school children. The program is a six-week program [with an optional 7th week consisting of aqua-week]. It is run by the Marlboro Township Recreation & Parks Commission.

Wineries

Future open space

The township has attempted to preserve the areas known as F&F properties, Stattel's Farm and McCarron Farm (also known as Golden Dale Farm) from future development. The last two farms are currently working farms and while the township has purchased the development rights on the property, their fate remains unknown.[141] The development rights of F&F property were purchased for $869,329 to keep the 79-acre (320,000 m2) site as open space.

Open space funding is paid for by a number of sources. State and local sources account for most of the funding. Marlboro obtains the funding from a special tax assessment. The town collects $600,000 annually from a local open space tax assessment of 2 cents per $100 of assessed valuation.[142]

Public safety

Emergency services

The Township of Marlboro has multiple departments which handle emergency services. In addition to the offices below, other departments can be reached through a countywide directory maintained by the Township of Marlboro.[143] The following are the emergency service departments in Marlboro Township:

Police

The police department was established in May 1962. At that time, there was one police officer who served the township. The Marlboro Township Police Department is composed of over 67 full-time police officers.[144] The current Chief of Police is Bruce E. Hall who started in this position in February 2009 following Police Chief Robert C. Holmes Sr. retiring suddenly on New Year's Eve 2008.[145]

- Office of Emergency Management - The Office of Emergency Management is responsible for preparing for and managing any declared or other large-scale emergency, event, or occurrence, either man-made or natural, which may occur within Marlboro Township. By law the Office of Emergency Management must have an Emergency Operation Plan (EOP) that addresses all of the possible/probable emergencies that may occur.

Fire Prevention Bureau

The Fire Prevention Bureau enforces the New Jersey Uniform Fire Code in all buildings, structures and premises, Condo development residential buildings and other owner-occupied residential buildings. The Fire Prevention Bureau does not enforce codes in residential units with fewer than three dwelling units.[146]

Fire and rescue squads

Marlboro Township has four volunteer fire companies and two volunteer first aid squads:[147]

- Fire companies[148]

- Marlboro Fire Co. No. 1

- Robertsville Volunteer Fire Company No. 1 (founded 1958)[149]

- Morganville Independent Volunteer Fire Company District 3[150]

- Morganville Volunteer Fire Company No. 1 (founded 1914)[151]

- First aid squads

Emergency notification system

SWIFT911 is a high speed notification program with the capability of delivering recorded warnings to the entire community or targeted areas, via telephone, email, text or pager. Messages can be transmitted through the Marlboro Township Police Department or Office of the Mayor and the system can contact up to four telephone numbers until reaching the designated party. Emergency and Non-emergency messages are also able to reach TTY (teletypewriter) phones used by those who are deaf or hard of hearing.[154]

Government

Local government

Marlboro Township is governed within the Faulkner Act under the Mayor-Council system of municipal government.[3] The township is one of 71 municipalities (of the 565) statewide that use this form of government.[155]

The governing body consists of the Mayor, who is elected directly, and the five-member Marlboro Township Council, with all elected positions chosen at-large in partisan voting to serve four-year terms of office on a staggered basis, with a municipal election conducted in odd-numbered years as part of the November general election. Three council seats come up for vote together and two other council seats come up for election together with the mayoral seat two years later. At a reorganization meeting held in January after each election, the Council selects a President and Vice-President from among its members. As the township's legislative body, the council sets policies, approves budgets, determines municipal tax rates, and passes resolutions and ordinances to govern the township. The Council also appoints citizen volunteers to certain advisory boards and the Zoning Board of Adjustment. The Council may investigate the conduct of any department, officer or agency of the municipal government. They have full power of subpoena as permitted by statute.

As of 2020, the Mayor of Marlboro Township is Democrat Jonathan Hornik, whose term of office ends December 31, 2019.[4] Members of the Marlboro Township Council are Council President Carol Mazzola (D, 2021), Council Vice President Jeff Cantor (D, 2021), Randi Marder (D, 2023), Scott Metzger (D, 2021) and Michael Scalea (D, 2023).[156][157][158][159][160]

In January 2015, the Township Council selected Mike Scalea from a list of three candidates nominated by the Demorcatic municipal committee to fill the vacant seat expiring in December 2015 of Frank LaRocca, who resigned earlier that month to take a seat as a municipal judge.[161]

Mayors of Marlboro

The following individuals have served as Mayor (or the other indicated title), since the Faulkner Act system was adopted in 1952:

- Leroy Van Pelt (1952 - 1954) - Van Pelt was Chairman of the Township Committee for the five preceding years in office. In 1952, the Faulkner Act changed the township leadership positions to the current Mayor-Council system.

- Dennis Buckley (1954 - 1958) - Township Chairman

- Charles T. "Specs" McCue (1958 - 1962) - Township Chairman

- Paul E. Chester (1962 - 1963) - Elected Mayor January 3, 1962 - Prior to election he served on the Township Committee.[162]

- Joseph A. Lanzaro (1963 - 1964)

- Walter Grubb (1964 - 1968)

- Charles T. "Specs" McCue (1968 - 1969) - Owning a grocery store on Main Street in Marlboro, his career started in 1942 under the old form of government. During his time in local government, he was Mayor for four terms and a member of the Planning Board for 8 years.[163]

- Walter Grubb (1969) - appointed to serve out for McCue who died in office. After the November general election in which Morton Salkind won the balance of the mayoral term, he and Grubb battled over who would fill the seat until January 1.[164]

- Morton Salkind (1969 - 1975)[165]

- Arthur Goldzweig (1976 - 1979)

- Saul Hornik (1980 - 1991)[166]

- Matthew Scannapieco (1992-2003)[167]

- Robert Kleinberg (2003 - 2005)

- Jonathan Hornik[4] (2005–present)

Local political issues

Political issues in Marlboro include land development and loss of open space, growth of population leading to the need for additional public schools and higher property taxes, and recurring instances of political corruption.

Former three-term mayor Matthew Scannapieco was arrested by the FBI and subsequently pleaded guilty to taking $245,000 in bribes from land developer Anthony Spalliero, in exchange for favorable rulings and sexual favors.[168][169] The same investigation has also resulted in charges against several other township officials as well as a Monmouth County Freeholder.

Federal, state and county representation

Marlboro Township is located in the 6th Congressional District[170] and is part of New Jersey's 13th state legislative district.[10][171][172] Prior to the 2011 reapportionment following the 2010 Census, Marlboro Township had been in the 12th state legislative district.[173] Prior to the 2010 Census, Marlboro Township had been split between the 6th Congressional District and the 12th Congressional District, a change made by the New Jersey Redistricting Commission that took effect in January 2013, based on the results of the November 2012 general elections.[173]

For the 116th United States Congress, New Jersey's Sixth Congressional District is represented by Frank Pallone (D, Long Branch).[174][175] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2021)[176] and Bob Menendez (Paramus, term ends 2025).[177][178]

For the 2018–2019 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 13th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Declan O'Scanlon (R, Little Silver) and in the General Assembly by Amy Handlin (R, Middletown Township) and Serena DiMaso (R, Holmdel Township).[179][180]

Monmouth County is governed by a Board of Chosen Freeholders consisting of five members who are elected at-large to serve three year terms of office on a staggered basis, with either one or two seats up for election each year as part of the November general election. At an annual reorganization meeting held in the beginning of January, the board selects one of its members to serve as Director and another as Deputy Director.[181] As of 2020, Monmouth County's Freeholders are Freeholder Director Thomas A. Arnone (R, Neptune City, term as freeholder ends December 31, 2022; term as freeholder director ends 2021),[182] Freeholder Deputy Director Susan M. Kiley (R, Hazlet Township, term as freeholder ends December 31, 2021; term as deputy freeholder director ends 2021),[183] Lillian G. Burry (R, Colts Neck Township, 2020),[184] Nick DiRocco (R, Wall Township, 2022),[185] and Patrick G. Impreveduto (R, Holmdel Township, 2020)[186].

Constitutional officers elected on a countywide basis are County clerk Christine Giordano Hanlon (R, 2020; Ocean Township),[187][188] Sheriff Shaun Golden (R, 2022; Howell Township),[189][190] and Surrogate Rosemarie D. Peters (R, 2021; Middletown Township).[191][192]

Politics

As of March 23, 2011, there were a total of 26,633 registered voters in Marlboro Township, of which 7,125 (26.8%) were registered as Democrats, 4,299 (16.1%) were registered as Republicans and 15,202 (57.1%) were registered as Unaffiliated. There were 7 voters registered to other parties.[193]

In the 2012 presidential election, Republican Mitt Romney received 53.5% of the vote (9,915 cast), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama with 45.6% (8,450 votes), and other candidates with 0.8% (154 votes), among the 18,636 ballots cast by the township's 27,821 registered voters (117 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 67.0%.[194][195] In the 2008 presidential election, Republican John McCain received 49.9% of the vote (10,014 cast), ahead of Democrat Barack Obama with 48.1% (9,663 votes) and other candidates with 0.8% (155 votes), among the 20,082 ballots cast by the township's 27,603 registered voters, for a turnout of 72.8%.[196] In the 2004 presidential election, Democrat John Kerry received 50.1% of the vote (9,378 ballots cast), outpolling Republican George W. Bush with 49.2% (9,218 votes) and other candidates with 0.3% (87 votes), among the 18,731 ballots cast by the township's 25,204 registered voters, for a turnout percentage of 74.3.[197]

In the 2013 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 73.7% of the vote (7,518 cast), ahead of Democrat Barbara Buono with 25.2% (2,574 votes), and other candidates with 1.0% (107 votes), among the 10,337 ballots cast by the township's 27,919 registered voters (138 ballots were spoiled), for a turnout of 37.0%.[198][199] In the 2009 gubernatorial election, Republican Chris Christie received 58.5% of the vote (7,355 ballots cast), ahead of Democrat Jon Corzine with 36.1% (4,541 votes), Independent Chris Daggett with 4.2% (533 votes) and other candidates with 0.6% (80 votes), among the 12,570 ballots cast by the township's 26,863 registered voters, yielding a 46.8% turnout.[200]

Education

Elementary schooling

The Marlboro Township Public School District serves students in pre-kindergarten through eighth grade.[201] As of the 2018–19 school year, the district, comprising eight schools, had an enrollment of 4,784 students and 440.5 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 10.9:1.[202] The district has eight school facilities: one pre-school, five elementary schools and two middle schools. The schools (with 2018–19 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[203]), are David C. Abbott Early Learning Center[204] with 226 students for kindergarten and preschool special education, Defino Central Elementary School[205] with 515 students in grades K-5 (opened 1957), Frank J. Dugan Elementary School[206] with 616 students in grades K–5 (opened 1987), Asher Holmes Elementary School[207] with 504 students in grades 1–5 (opened 1973), Marlboro Elementary School[208] with 489 students in grades K–5 (opened 1971), Robertsville Elementary School[209] with 486 students in grades 1–5 (opened 1968), Marlboro Memorial Middle School[210] with 883 students in grades 6-8 (opened 2003) and Marlboro Middle School[211] with 1,042 students in grades 6-8 (opened in 1976).[212]

High school

Most public students in ninth through twelfth grades from Marlboro Township attend Marlboro High School, which is part of the Freehold Regional High School District, with some Marlboro students attending Colts Neck High School.[213] The district also serves students from Colts Neck Township, Englishtown, Farmingdale, Freehold Borough, Freehold Township, Howell Township and Manalapan Township.[214] Many Marlboro students attend the various Learning Centers and Academies available at other district high schools and students from other municipalities in the district attend Marlboro High School's Business Learning Center.[215] As of the 2018–19 school year, Marlboro High School had an enrollment of 1,822 students and 127.2 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 14.3:1[216] and Colts Neck High School had an enrollment of 1,358 students and 94.0 classroom teachers (on an FTE basis), for a student–teacher ratio of 14.4:1.[217] The FRHSD board of education has nine members, who are elected to three-year terms from each of the constituent districts.[218] Each member is allocated a fraction of a vote that totals to nine points, with Marlboro Township allocated one member, who has 1.4 votes.[219]

Private schools

The High Point Schools are a group of private special education elementary and adolescent schools located on a 10-acre (40,000 m2) campus in the Morganville section of the township. The schools have been providing educational and therapeutic services for students ages 5 – 21 who have emotional, behavioral and learning difficulties for 45 years. The staff-to-student ratio is 1:3.[220] The school was built on the Doyle apple orchard.[221]

Among other private schools serving Marlboro children is the Solomon Schechter Day School of Greater Monmouth County, a Pre-K to Grade 8 Jewish Day School, which is a member of the Solomon Schechter Day School Association, the educational arm of the United Synagogue of America.[222] Shalom Torah Academy in Morganville is an independent Jewish day school that serves students from the age of two through eighth grade.[223]

Now defunct, the Devitte Military Academy was found in 1918 by Major Leopold Devitte. Starting out as co-educational residential school, in 1920, it became an all-male school. The campus consisted of five buildings and other sleeping cottages. All buildings but one were demolished. One of the buildings was re-purposed and adapted for the Hindu-American Temple which currently occupies the campus.[224][225]

School summary

| School name | Grades | Public | Sports facilities available | Student population | Notes | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| David C. Abbott Early Learning Center | Pre-School & Special Ed. | Link | ||||

| Asher Holmes Elementary School | Link | |||||

| Defino Central Elementary School | Link | |||||

| Frank J. Dugan Elementary School | Link | |||||

| Marlboro Elementary School | ||||||

| Robertsville Elementary School | Link | |||||

| Marlboro Middle School | Teacher : Student Ratio is 1:13 [226] | Link | ||||

| Marlboro Memorial Middle School | Link | |||||

| Solomon Schechter | Jewish Day School | Link | ||||

| High Point Schools | School for Emotional & Behavioral Problems | Link | ||||

| Marlboro High School | Link | |||||

| Collier High School | Private school for students with disabilities | [228] |

Library

The Marlboro Free Public Library is open six days a week (closed Sundays). There are meeting rooms for groups to gather and hold meetings or parties. The children's department is large and well-lit, with a diverse selection of books. There is no additional charge for movie rentals.[229]

Little Free Library

Marlboro Township has two Little Free Library locations at opposite sides of the town. The first is in Morganville subdivision and the second is toward the town center, close to the town hall.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Stage Coach Station

Gone now, the intersection of County Route 520 and Tennent Road in Robertsville once was a stage coach Station. The stage coach line was a layover location for those traveling between Jersey City and Atlantic City.[230]

Railroad

Started in 1867 (completed in 1877) as the Monmouth County Agricultural Railroad; A train rail ran through Marlboro. There were four stops in Marlboro (Bradevelt, Marlboro, Morganville, and Wickatunk).[231] The Railroad line was largely abandoned by the 70. Owned by Jersey Central in the 90's it was leased to the Monmouth County Park System in a Rail to Trail process.

Roads and highways

_in_Marlboro_Township%2C_Monmouth_County%2C_New_Jersey.jpg)

As of May 2010, the township had a total of 229.71 miles (369.68 km) of roadways, of which 201.56 miles (324.38 km) were maintained by the municipality, 11.05 miles (17.78 km) by Monmouth County and 17.10 miles (27.52 km) by the New Jersey Department of Transportation.[232]

The car is the most common mode of transportation in Marlboro Township. The main public thoroughfares in Marlboro Township are U.S. Route 9, Route 18, County Route 520 and Route 79. These routes provide access to major highways including the Garden State Parkway and the New Jersey Turnpike. Taxi services are also available through a number of local private companies.

Public transportation

There are multiple public transportation options available, including bus, rail, air and ferry service. NJ Transit provides bus service to and from the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown Manhattan on the 131, 135 and 139 routes; on the 64 and 67 and from both Jersey City and Newark.[233] The Matawan train station is a heavily used train station on NJ Transit's North Jersey Coast Line, providing service to New York Pennsylvania Station via Secaucus Junction, with a transfer available for trains to Newark Liberty International Airport. However, both options provide significant problems in terms of lack of available parking, which may require waiting periods of more than a year for a permit and private parking options are very expensive.[48]

Ferry service is available through the SeaStreak service in Highlands, a trip that involves about a 25-minute drive on secondary roads from Marlboro Township to reach the departing terminal. SeaStreak offers ferry service to New York City with trips to Pier 11 (on the East River at Wall Street) and East 35th Street in Manhattan.[234]

Following the closure of the Marlboro Airport, Monmouth Executive Airport in Farmingdale, Old Bridge Airport and Mar Bar L Farms municipal airport supply short-distance flights to surrounding areas and are now the closest air transportation services. The closest major airport is Newark Liberty International Airport, which is 33.1 miles (53.3 km) (about 42 minutes drive) from the center of Marlboro Township.

Health care

Marlboro Township is served by CentraState Healthcare System in Freehold Township, a 282-bed medical facility serving central Monmouth County. The next closest hospitals Raritan Bay Medical Center Old Bridge Division, located in Old Bridge Township and Bayshore Community Hospital, located in Holmdel Township. The closest major university hospitals are Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick and Jersey Shore University Medical Center in Neptune Township.

Industrial Park

In 1958 the township set aside 1500 acres for industrial growth. Officially known as the Marlboro Industrial Park, it is located off Vanderburg Road.[230] The industrial park slogan, created by John B. Ackley, is "You get a lot to like in Marlboro".[235]

Contaminated and Superfund sites

Underground storage tanks

The NJDEP lists 39 known locations of underground storage tank contamination in Marlboro Township.[236]

Burnt Fly Bog

Located off Tyler Lane and Spring Valley Road on the Old Bridge Township border, the area of Burnt Fly Bog in Marlboro Township is listed as a Superfund clean-up site. It is a rural area covering approximately 1,700 acres (6.9 km2), most of it in Marlboro Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. During the 1950s and early 1960s, many unlined lagoons were used for storage of waste oil. As a result, at least 60 acres (240,000 m2) of the bog have been contaminated. In addition to the current contaminated area, the site still consists of: four lagoons; an approximately 13,000-cubic-yard mound of sludge; and an undetermined number of exposed and buried drums. The site is a ground water discharge area for the Englishtown Aquifer. In this bog, ground water, surface water, and air are contaminated by oil and various organic chemicals. Contaminants known to be present include ethylbenzene, methylene chloride, tetrachloroethylene, toluene, base neutral acids, metals, PAHs, PCBs, unknown liquid waste, and VOCs.[237]

A number of studies have been mounted starting in 1981. At that time the EPA awarded a Cooperative Agreement and funds to New Jersey under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. Early in 1982, EPA used CERCLA funds to install a 900-foot (270 m) fence and repair a 6-foot (1.8 m) section of a dike. In 1983, the state completed (1) a field investigation to study the ground water, (2) a feasibility study for removal of contaminated soil and drums, and (3) a feasibility study for closing the site. EPA and the state continue negotiating agreements for further cleanup activities.[238]

Up to the year 2003, 33,600 cubic yards or sedimentation, sludge and soil have been removed for disposal and incineration.[239] The area was then back filled with top soil. In June 2011, a five-year review of the site was published. At that time the remediation status was complete as of date: 9/21/2004. Finally a fence has been installed around the entire site to restrict access and protect human health but has been breached in several locations. The downstream area was cleaned up to residential levels. It was recommended that the NJDEP continued monitoring off Site groundwater for five years. The final suggestion was "Since hazardous substances, pollutants or contaminants remain at the Site which do not allow for unlimited use or unrestricted exposure, in accordance with 40 CFR 300.430 (f) (4) (ii), the remedial action for the Site shall be reviewed no less often than every five years. EPA will conduct another five-year review prior to June 2016."[240]

Imperial Oil Co.

This 15-acre (61,000 m2) part of land was owned by Imperial Oil Co./Champion Chemicals. The site was added to the National Priorities List of Superfund sites in 1983.[241] The site consists of six production, storage, and maintenance buildings and 56 above-ground storage tanks. Known contamination includes PCBs, arsenic, lead and total petroleum hydrocarbons. A number of companies may have been responsible for waste oil discharges and arsenical pesticides released to a nearby stream as industrial operations date back to 1912. The area is protected by a fence that completely encloses it. This site is being addressed through Federal and State actions. Mayor Hornik of Marlboro Township, described the polluted site as "one of the worst in the country."[242]

In 1991, EPA excavated and disposed of an on-site waste filter clay pile. In 1997, EPA posted warning signs on the Henry Hudson Trail which is located near the site and the tarp covering the remaining waste filter clay pile was replaced to prevent human contact and limit the migration of the contamination. Arsenic and metals continued to be found in soils in the vicinity of this site.[243] In April 2002, EPA excavated and disposed of a 25-foot (7.6 m) by 25-foot (7.6 m) area of soil containing a tar-like material discovered outside of the fenced area. The presence of elevated levels of PCBs and lead in this material may have presented a physical contact threat to trespassers. In April 2004, 18,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil were removed from Birch Swamp Brook and adjacent properties. In August 2007, EPA arranged for 24-hour security at the site, given that Imperial Oil declared bankruptcy and ceased operations at the site during July 2007.[244]

The EPA announced in 2009 the start-up of remediation activities for contaminated soils at the site now called "Operable Unit 3" (OU3). Marlboro Township has benefited from the $10–$25 million in stimulus funding to pay for the cost of this cleanup.[245]

On May 3, 2012, the EPA held a press conference. The spokesman "Enck said a $50 million effort over 25 years has cleaned the property, removing 4,600 gallons of oil that pooled on the land, along with 30 million gallons of ground water and 180,000 cubic yards of soil." A total of $17 million for the clean-up came from the federal Superfund program, with $33 million from the American Resource and Recovery Act.[246][247]

Marlboro Middle School

Marlboro Middle School contamination was an issue which was handled by the state and local level. It was not a Superfund site. This field was an Angus bull farm prior to being donated to the town for school construction. During the soccer fields improvement program, tests were conducted at the soccer complex which showed elevated levels of unspecified contaminants. The Mayor closed the fields as soon as the test results came in. The township then applied for and received a grant to help with the remediation work. Marlboro received money from the Hazardous Discharge Site Remediation Fund to conduct soil remediation at the soccer fields.[248]

Entron Industries site

This property clean-up is being handled through the NJEDA and is not considered a Superfund clean-up site. The site is located at the northeastern intersection of Route 79 and Beacon Hill Road. There were a total of 10 buildings on the site along with wooded areas. Investigations found the presence of a variety of unspecified environmental contaminants associated with the construction of rocket launcher parts. In addition, investigations included possible groundwater contamination on the property. There are no current known plans for clean-up, however, public hearings have been held to start the process of clean-up and redevelopment of the area.[249] Marlboro Township was given a total of $200,000 in two different grants to complete remedial investigation of the site by the NJEDA.[250] The mayor has suggested it may take up to $5 million to clean up the land.[251]

After a number of public hearings,[252] on July 14, 2011, a resolution was put forth authorizing the execution of the redevelopment agreement between The Township Of Marlboro and K-Land Corporation For The Property Known As Tax Block 132, Lot 18 (the Entron Industries site).[253] The developer suggested an investment of $100 million to clean up and develop the site.[251] The site is currently under redevelopment. K-land and Marlboro reached an agreement for the development of the Property to include 365 residential units, 33% of which would be set aside as affordable units.[254] The Redeveloper created "Camelot at Marlboro".[255] This housing development has been completed and the property has been restored.

Arky property

The Arky property is a non-Superfund clean-up site with focus by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, located at 217 Route 520 in Marlboro Township. This 22-acre (89,000 m2) site was an automobile junkyard. Contamination consisted of volatile organic compounds in the groundwater and soil contamination of metals, trichloroethylene (TCE), methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).[256] Initial clean-up consisted of removal of the contaminated soil. Also found were buried drums of unknown product. There were 22 drums removed. In 1998, NJDEP conducted a second drum removal action. They excavated 70 buried drums and removed some of the contaminated soil around the drums. The drums of hazardous wastes had been crushed and buried prior to 1987. To further monitor the property, NJDEP has installed additional monitor wells near the site to collect ground water samples. Investigations are continuing to determine if additional contamination is present on the site which would require clean-up actions.[257]

DiMeo property

This 77-acre (310,000 m2) property[258] was purchased by Marlboro Township under P.B. 938-05[259] for recreational uses, including walking-jogging trails, a playground area and a picnic grove area.[260] The property is located at Pleasant Valley and Conover roads. Clean-up is being handled through the NJEDA and is not considered a Superfund clean-up site. In 2004, Schoor DePalma[261] addressed the contaminated soil on the property. The soil on this property had widespread hazardous levels of arsenic, lead, pesticides and petroleum related contamination; consistent with farming-related operations.[260] Additionally, the property contains a pond that is polluted with arsenic, a common agricultural contaminant.[262]

After clean-up, deep monitoring wells were created. In 2007, Birdsall Engineering investigated arsenic and pesticide contamination on the property. Two isolated hot spots were found with high levels of pesticides. The clean-up work was funded by the state farmland preservation program.[263] In 2008, Marlboro Township received state funds for continued clean-up and monitoring by the NJEDA.[264]

This property is on the border of the land that formerly housed the Marlboro State Psychiatric Hospital. This presents its own possibilities, should the Township of Marlboro purchase the hospital property.[265]

Big Brook Park

This site is being addressed through state and local department and funds and is not a superfund clean-up site. In 1997, the Monmouth County Park System bought 378 acres (1.53 km2) of the closed Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital land. The intent is to create a regional park, similar to Holmdel Park.[266] It is also expected to be home to part of the Henry Hudson Trail.[267] The plans for the property have not been completed, in part due to potential environmental contamination.[268] Preliminary environmental studies by Birdsall Engineering found asbestos and oil contamination on the grounds.[269] The land is contaminated with arsenic, reportedly a byproduct of farming.[266] In an attempt to further classify the contamination, the Luis Berger Group has done further testing on this site. They are reporting that the arsenic found on the site is "actually a naturally occurring condition in local and regional soil in this area". Additionally they reported that the site contamination found in the prior study was caused by a number of factors, including a former septic system (Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital discharged the effluent from the hospital into Big Brook[270]), pesticide mixing building, fuel oil underground storage tank, and construction debris. This evaluation made the following recommendations to the NJDEP:

- Tank storage closure and removal—Excavation of surficial soils along with post excavation sampling

- Removal of septic systems

- Asbestos abatement

- Wetlands restoration

Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital

The site of the closed Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital has on-site contamination—it is not considered a Superfund clean-up site. Mayor Jonathan Hornik estimates it could cost more than $11 million to clean up. Mayor Jonathan Hornik stated that the state clearly has the responsibility for cleaning up the site. He however, stated that in the interest of getting it done, the township may have to show some flexibility in helping the state defray the costs.[271] In addition to the contamination on the site, the old buildings from the hospital are now in a state of decay and are being demolished.

Murray property

This site is being addressed through state and local funds and is not considered a Superfund clean-up site. The property is contaminated with an undisclosed substance. To clean up the contamination, 1,708 cubic yards of soil was removed. The site is located on Prescott Drive, Block 233 Lot 13.[272]

Sister cities

Marlboro has two sister cities:

Marlboro's first sister city, Nanto was formerly known as Jōhana (Nanto was formed after the merger of the towns of Fukuno, Inami and Jōhana). It was officially Marlboro's sister city in August 1991 as part of an agreement signed by mayor Saul Hornik with Johana's mayor.[273]

Marlboro's second sister city, Wujiang[274] is an urban city in Jiangsu Province of southeast China. It has been regarded for "The Land of Rice and Fish" and "The Capital of Silk". It is recently known for being the "Capital of Electronics". Wujiang officially became a sister city with Marlboro in December 2011.[275]

There are youth exchanges with each of these cities. In February 2011, there were 41 exchange students from Wujiang City, China welcomed into the homes of Marlboro. They were also welcomed August 2012 and August 2014. However, beginning in 2014, exchange students from Wujiang City visit Marlboro every other summer.[276]

Notable people

People who were born in, residents of, or otherwise closely associated with Marlboro Township include:

- John Boyd (1679-1708), the first Presbyterian minister ordained in America.[277]

- Chris Carrino, sports play-by-play announcer.[278]

- Robert J. Collier (1876-1918), Editor of Collier's Weekly who owned the publishing company P.F. Collier & Son[279][280]

- Frank Dicopoulos (born 1957), actor (Guiding Light).[281]

- Max Ehrich (born 1991), actor from High School Musical 3: Senior Year.[282]

- Jeff Feuerzeig (born 1964), film screenwriter and director.[283]

- Ronald "Monkey Man" Filocomo, Bonanno crime family associate, convicted murderer of Bonanno capo Dominick "Sonny Black" Napolitano.[284]

- Josh Flitter (born 1994), actor most noted for starring in the movies The Greatest Game Ever Played and Nancy Drew.[285]

- Elmer H. Geran (1875-1954), politician represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district from 1925 to 1927 after having served in the New Jersey General Assembly in 1911 and 1912.[286]

- Hunter Gorskie (born 1991), professional soccer defender for the New York Cosmos.[287]

- Mark Haines (1946-2011), host on the CNBC television network.[288]

- Garret Hobart (1844-1899), 24th Vice President of the United States.[289]

- Asher Holmes (1740 - 1808), Lived in Pleasant Valley... Colonel in the Revolutionary War who saw battle, elected first Sheriff of Monmouth county and in 1774, he was appointed to the Committee of Correspondence (a forerunner to the Continental Congress)... He was a member of the state legislative council from 1786 to 1787.[290]

- John D. Honce (1834 - 1915), member of the New Jersey General Assembly who was a champion of fisherman and clammers along the shore.[291]

- Mike Kamerman, guitar player for the indie pop band Smallpools.[292]

- Ellen Karcher (born 1964), New Jersey state senator from 2004 to 2008.[293]

- Dan Klecko (born 1981), NFL Fullback for the Philadelphia Eagles.[294]

- Jeff Kwatinetz (born 1965), Hollywood talent manager.[295]

- Craig Mazin (born 1971), screenwriter of Scary Movie 3 and Scary Movie 4.[296]

- Idina Menzel (born 1971 as Idina Kim Mentzel), lived in Marlboro from kindergarten to third grade.[297]

- Adam Mesh (born 1975), television reality show contestant on NBC's Average Joe and Average Joe: Adam Returns.[298]

- Akash Modi (born 1995), artistic gymnast who represented the United States at the 2018 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships.[299]

- Jim Nantz (born 1959), sportscaster.[300][301]

- Declan O'Scanlon (born 1963), member of the New Jersey General Assembly since 2012.[302]

- Kal Penn (born 1977), actor who has appeared in Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle and House.[303]

- Melissa Rauch (born 1980), actress (The Big Bang Theory, Best Week Ever).[304][305]

- Tony Reali (born 1978), television personality and host (Around the Horn).[306]

- John Reid (1683 - 1723), County Judge and Surveyor-General of East Jersey who created one of the earliest surviving map of East Jersey in 1686 and was one of the first members elected to the New Jersey Assembly following its creation in 1702.[307]

- Howie Roseman (born 1975), General Manager of the Philadelphia Eagles.[308]

- Felicia Stoler, host of TLC's Honey, We're Killing the Kids.[309]

- David Stone (born 1966), Broadway producer (Wicked and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee).[310]

- Rev. John Tennent (1707-1732) Presbyterian Minister who provided initial thought into the "Great Awakening" in Presbyterian theology. Buried at Old Scot's Burial Ground. A tablet, erected by the Presbyterian Synod of New Jersey in 1915 commemorates his life is near his grave.[311][312]

- Paul Wesley (born 1982), actor who has appeared on The Vampire Diaries.[313]

- Sharnee Zoll-Norman (born 1986), point guard who has played for the Chicago Sky of the WNBA.[314]

References

- 2010 Census Gazetteer Files: New Jersey County Subdivisions, United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2015.

- US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990 , United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- 2012 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, March 2013, p. 63.

- Mayor Jonathan Hornik, Township of Marlboro. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 2020 New Jersey Mayors Directory, New Jersey Department of Community Affairs. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- Administration, Marlboro Township. Accessed February 26, 2020.

- Municipal Clerk, Marlboro Township. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Township of Marlboro, Geographic Names Information System. Accessed March 7, 2013.

- DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Marlboro township, Monmouth County, New Jersey Archived 2020-02-12 at Archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 17, 2011.

- Municipalities Sorted by 2011-2020 Legislative District, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010 for Marlboro township, Monmouth County, New Jersey Archived 2012-05-06 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Accessed December 17, 2011.

- QuickFacts for Marlboro township, Monmouth County, New Jersey; Monmouth County, New Jersey; New Jersey from Population estimates, July 1, 2019, (V2019), United States Census Bureau. Accessed May 21, 2020.

- GCT-PH1 Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - State -- County Subdivision from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for New Jersey Archived 2020-02-12 at Archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 20, 2012.

- Look Up a ZIP Code for Marlboro, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed December 6, 2011.

- Zip Codes, State of New Jersey. Accessed September 9, 2013.

- Area Code Lookup - NPA NXX for Marlboro, NJ, Area-Codes.com. Accessed September 9, 2013.

- U.S. Census website , United States Census Bureau. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Geographic codes for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed September 1, 2019.

- US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Table 7. Population for the Counties and Municipalities in New Jersey: 1990, 2000 and 2010, New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, February 2011. Accessed July 13, 2012.

- Snyder, John P. The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 182. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed August 30, 2015.

- Lazaretto: Time Line Archived 2008-05-17 at the Wayback Machine, Lazaretto Quarantine Station. Accessed August 30, 2015.

- William S. Hornor, This Old Monmouth of Ours, published 1932, Page 190

- History of Colts Neck, Colts Neck Township. Accessed December 4, 2016.

- Winson, Terrie. "Lenni Lenape", Reading Area Community College, March 2002, backed up by the Internet Archive as of December 11, 2008. Accessed July 16, 2015.

- Native Americans, Penn Treaty Museum. Accessed July 16, 2015.

- "The Lenapes: A study of Hudson Valley Indians", Welcome to Marist Country, backed up by the Internet Archive as of January 27, 2012. Accessed July 16, 2015.

- Thomas, JD. "The Colonies' First and New Jersey's Only Indian Reservation", Accessible Archives, August 29, 2013. Accessed July 16, 2015.

- Our Tribal History, The Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape. Accessed July 16, 2015.

- Marlboro Municipal Records, Monmouth County, New Jersey. Accessed June 29, 2011.

- nation.txt History of The Lenape Nation, University of Nevada, Reno, backed up by the Internet Archive as of January 16, 2010. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- "Weequehela - Indian King of Central New Jersey". Spotswoodhistory.tripod.com. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–76.

- "Early Dutch Settlers to Monmouth County, New Jersey - Part 9". Distantcousin.com. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- "Brotherton & Weekping Indian Communities of NJ". Brotherton-weekping.tripod.com. January 25, 1957. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- Religious Society Of Friends (Quakers) Archived 2011-05-01 at the Wayback Machine ub 1692. Freehold Township website. Accessed April 5, 2006.

- St. Peter's Episcopal Church History Archived 2011-05-01 at the Wayback Machine. Freehold Township website. Accessed April 5, 2006.

- "Cemeteries: Topanemus Burying Ground: Freehold, Monmouth Co, NJ". Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- Metzgar, Dick. "Pastor proud of church's involvement in community; Work continuing on St. Peter's restoration", News Transcript, October 4, 2000. Accessed January 20, 2018.

- "Early Dutch Settlers of Monmouth County, New Jersey". Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- "Monmouth County" from Historic Roadsides of New Jersey, Get NJ. Accessed December 4, 2016.

- Hutchinson, Viola L. The Origin of New Jersey Place Names, New Jersey Public Library Commission, May 1945. Accessed July 16, 2015.

- History of Monmouth County, New Jersey, 1664-1920, Volume 3 - Published 1922