Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to before recorded history.

Shipbuilding and ship repairs, both commercial and military, are referred to as "naval engineering". The construction of boats is a similar activity called boat building.

The dismantling of ships is called ship breaking.

History

Pre-history

Archaeological evidence indicates that anatomically modern humans arrived on Borneo at least 120,000 years ago, probably by sea from the Asian mainland during an ice age period when the sea was lower and distances between islands shorter (See History of Papua New Guinea). The ancestors of Australian Aborigines, Papuans, Melanesians, Negritos, and Onges also went across the Lombok Strait to Sahul by boat over 50,000 years ago.

4th millennium BC

Evidence from Ancient Egypt shows that the early Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull as early as 3100 BC. Egyptian pottery as old as 4000 BC shows designs of early boats or other means for navigation. The Archaeological Institute of America reports[1] that some of the oldest ships yet unearthed are known as the Abydos boats. These are a group of 14 ships discovered in Abydos that were constructed of wooden planks which were "sewn" together. Discovered by Egyptologist David O'Connor of New York University,[2] woven straps were found to have been used to lash the planks together,[1] and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams.[1] Because the ships are all buried together and near a mortuary belonging to Pharaoh Khasekhemwy,[2] originally they were all thought to have belonged to him, but one of the 14 ships dates to 3000 BC,[2] and the associated pottery jars buried with the vessels also suggest earlier dating.[2] The ship dating to 3000 BC was about 75 feet (23 m) long[2] and is now thought to perhaps have belonged to an earlier pharaoh.[2] According to professor O'Connor, the 5,000-year-old ship may have even belonged to Pharaoh Aha.[2]

3rd millennium BC

Early Egyptians also knew how to assemble planks of wood with treenails to fasten them together, using pitch for caulking the seams. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter vessel sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza in the Fourth Dynasty around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque. Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten the planks of this ship together with mortise and tenon joints.[1]

The oldest known tidal dock in the world was built around 2500 BC during the Harappan civilisation at Lothal near the present day Mangrol harbour on the Gujarat coast in India. Other ports were probably at Balakot and Dwarka. However, it is probable that many small-scale ports, and not massive ports, were used for the Harappan maritime trade.[3] Ships from the harbour at these ancient port cities established trade with Mesopotamia.[4] Shipbuilding and boatmaking may have been prosperous industries in ancient India.[5] Native labourers may have manufactured the flotilla of boats used by Alexander the Great to navigate across the Hydaspes and even the Indus, under Nearchos.[5] The Indians also exported teak for shipbuilding to ancient Persia.[6] Other references to Indian timber used for shipbuilding is noted in the works of Ibn Jubayr.[6]

2nd millennium BC

The ships of Ancient Egypt's Eighteenth Dynasty were typically about 25 meters (80 ft) in length, and had a single mast, sometimes consisting of two poles lashed together at the top making an "A" shape. They mounted a single square sail on a yard, with an additional spar along the bottom of the sail. These ships could also be oar propelled.[7] The ocean and sea going ships of Ancient Egypt were constructed with cedar wood, most likely hailing from Lebanon.[8]

The ships of Phoenicia seem to have been of a similar design.

1st millennium BC

The naval history of China stems back to the Spring and Autumn period (722 BC–481 BC) of the ancient Chinese Zhou Dynasty. The Chinese built large rectangular barges known as "castle ships", which were essentially floating fortresses complete with multiple decks with guarded ramparts. However, the Chinese vessels during this era were essentially fluvial (riverine). True ocean-going fleets did not appear until the 10th century Song dynasty.[9][10]

There is considerable knowledge regarding shipbuilding and seafaring in the ancient Mediterranean.[11] Malay people independently invented junk sails, made from woven mats reinforced with bamboo, at least several hundred years BC.[12]

Early 1st millennium AD

The ancient Chinese also built ramming vessels as in the Greco-Roman tradition of the trireme, although oar-steered ships in China lost favor very early on since it was in the 1st century China that the stern-mounted rudder was first developed. This was dually met with the introduction of the Han Dynasty junk ship design in the same century. It is thought that the Chinese had adopted the Malay junk sail by this period,[12] although a UNESCO study argues that the Chinese were using square sails during the Han dynasty and adopted the Malay junk sail later, in the 12th century.[9]

The Malay and Javanese people, started building large seafaring ships about 1st century AD.[13] These ships used 2 types of sail of their invention, the junk sail and tanja sail. Large ships are about 50–60 metres (164–197 ft) long, had 5.2–7.8 metres (17–26 ft) tall freeboard,[14] each carrying provisions enough for a year,[15] and could carry 200–1000 people. This type of ship favored by Chinese travelers, because they did not built seaworthy ships until around 8–9th century AD.[16]

Southern Chinese junks were based on keelled and multi-planked Austronesian jong (known as po by the Chinese, from Javanese or Malay perahu - large ship).[17]:613[18]:193 Southern Chinese junks showed characteristics of Austronesian jong: V-shaped, double-ended hull with a keel, and using timbers of tropical origin. This is different from northern Chinese junks, which are developed from flat bottomed riverine boats.[19]:20–21 The northern Chinese junks had flat bottoms, no keel, no frames (only water-tight bulkheads), transom stern and stem, would have been built out of pine or fir wood, and would have its planks fastened with iron nails or clamps.[17]:613

Archeological investigations done at Portus near Rome have revealed inscriptions indicating the existence of a 'guild of shipbuilders' during the time of Hadrian.[20]

Medieval Europe, Song China, Abbasid Caliphate, Pacific Islanders, Ming China

Until recently, Viking longships were seen as marking a very considerable advance on traditional clinker-built hulls of plank boards tied together with leather thongs.[21] This consensus has recently been challenged. Haywood[22] has argued that earlier Frankish and Anglo-Saxon nautical practice was much more accomplished than had been thought, and has described the distribution of clinker vs. carvel construction in Western Europe (see map ). An insight into ship building in the North Sea/Baltic areas of the early medieval period was found at Sutton Hoo, England, where a ship was buried with a chieftain. The ship was 26 metres (85 ft) long and, 4.3 metres (14 ft)[23] wide. Upward from the keel, the hull was made by overlapping nine strakes on either side with rivets fastening the oaken planks together. It could hold upwards of thirty men.

Sometime around the 12th century, northern European ships began to be built with a straight sternpost, enabling the mounting of a rudder, which was much more durable than a steering oar held over the side. Development in the Middle Ages favored "round ships",[24] with a broad beam and heavily curved at both ends. Another important ship type was the galley which was constructed with both sails and oars.

The first extant treatise on shipbuilding was written c. 1436 by Michael of Rhodes,[25] a man who began his career as an oarsman on a Venetian galley in 1401 and worked his way up into officer positions. He wrote and illustrated a book that contains a treatise on ship building, a treatise on mathematics, much material on astrology, and other materials. His treatise on shipbuilding treats three kinds of galleys and two kinds of round ships.[26]

Outside Medieval Europe, great advances were being made in shipbuilding. The shipbuilding industry in Imperial China reached its height during the Song Dynasty, Yuan Dynasty, and early Ming Dynasty. The mainstay of China's merchant and naval fleets was the junk, which had existed for centuries, but it was at this time that the large ships based on this design were built. During the Sung period (960–1279 AD), the establishment of China's first official standing navy in 1132 AD and the enormous increase in maritime trade abroad (from Heian Japan to Fatimid Egypt) allowed the shipbuilding industry in provinces like Fujian to thrive as never before. The largest seaports in the world were in China and included Guangzhou, Quanzhou, and Xiamen.

In the Islamic world, shipbuilding thrived at Basra and Alexandria, the dhow, felucca, baghlah and the sambuk, became symbols of successful maritime trade around the Indian Ocean; from the ports of East Africa to Southeast Asia and the ports of Sindh and Hind (India) during the Abbasid period.

At this time islands spread over vast distances across the Pacific Ocean were being colonised by the Melanesians and Polynesians, who built giant canoes and progressed to great catamarans.

Ming China

Shipbuilders in the Ming dynasty (1368~1644) were not the same as the shipbuilders in other Chinese dynasties, due to hundreds of years of accumulated experiences and rapid changes in the Ming dynasty. Shipbuilders in the Ming dynasty primarily worked for the government, under command of the Ministry of Public Works.

Early Ming (1368~1476)

During the early years of the Ming dynasty, the Ming government maintained an open policy towards sailing. Between 1405 and 1433, the government conducted seven diplomatic Ming treasure voyages to over thirty countries in Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East and Eastern Africa. The voyages were initiated by the Yongle Emperor, and led by the Admiral Zheng He. Six voyages were conducted under the Yongle Emperor's reign, the last of which returned to China in 1422. After the Yongle Emperor's death in 1424, his successor the Hongxi Emperor ordered the suspension of the voyages. The seventh and final voyage began in 1430, sent by the Xuande Emperor. Although the Hongxi and Xuande Emperors did not emphasize sailing as much as the Yongle Emperor, they were not against it. This led to a high degree of commercialization and an increase in trade. Large numbers of ships were built to meet the demand.[27][28]

The Ming voyages were large in size, numbering as many as 300 ships and 28,000 men.[29] The shipbuilders were brought from different places in China to the shipyard in Nanjing, including Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Fujian, and Huguang (now the provinces of Hubei and Hunan). One of the most famous shipyards was Long Jiang Shipyard (zh:龙江船厂), located in Nanjing near the Treasure Shipyard where the ocean-going ships were built.[27] The shipbuilders could built 24 models of ships of varying sizes.[27]

Several types of ships were built for the voyages, including Shachuan (沙船), Fuchuan (福船) and Baochuan (treasure ship) (宝船).[30] Zheng He's treasure ships were regarded as Shachuan types, mainly because they were made in the treasure shipyard in Nanjing. Shachuan, or 'sand-ships', are ships used primarily for inland transport.[27] However, in recent years, some researchers agree that the treasure ships were more of the Fuchuan type. It is said in vol.176 of San Guo Bei Meng Hui Bian (三朝北盟汇编) that ships made in Fujian are the best ones.[30] Therefore, the best shipbuilders and laborers were brought from these places to support Zheng He's expedition.

The shipyard was under the command of Ministry of Public Works. The shipbuilders had no control over their lives. The builders, commoner's doctors, cooks and errands had lowest social status.[31] The shipbuilders were forced to move away from their hometown to the shipyards. There were two major ways to enter the shipbuilder occupation: family tradition, or apprenticeship. If a shipbuilder entered the occupation due to family tradition, the shipbuilder learned the techniques of shipbuilding from his family and is very likely to earn a higher status in the shipyard. Additionally, the shipbuilder had access to business networking that could help to find clients. If a shipbuilder entered the occupation through an apprenticeship, the shipbuilder was likely a farmer before he was hired as a shipbuilder, or he was previously an experienced shipbuilder.

Many shipbuilders working in the shipyard were forced into the occupation. The ships built for Zheng He's voyages needed to be waterproof, solid, safe, and have ample room to carry large amounts of trading goods. Therefore, due to the highly commercialized society that was being encouraged by the expeditions, trades, and government policies, the shipbuilders needed to acquire the skills to build ships that fulfil these requirements.

Shipbuilding was not the sole industry utilising Chinese lumber at that time; the new capital was being built in Beijing from approximately 1407 onwards,[27] which required huge amounts of high-quality wood. These two ambitious projects commissioned by Emperor Yongle would have had enormous environmental and economic effects, even if the ships were half the dimensions given in the History of Ming. Considerable pressure would also have been placed on the infrastructure required to transport the trees from their point of origin to the shipyards.[27]

Shipbuilders were usually divided into different groups and had separate jobs. Some were responsible for fixing old ships; some were responsible for making the keel and some were responsible for building the helm.

- It was the keel that determined the shape and the structure of the hull of Fuchuan Ships. The keel is the middle of the bottom of the hull, constructed by connecting three sections; stern keel, main keel and poop keel. The hull spreads in the arc towards both sides forming the keel.[30]

- The helm was the device that controls direction when sailing. It was a critical invention in shipbuilding technique in ancient China and was only used by the Chinese for a fairly long time. With a developing recognition of its function, the shape and configuration of the helm was continually improved by shipbuilders.[30] The shipbuilders not only needed to build the ship according to design, but needed to acquire the skills to improve the ships.

Late Ming (1478–1644)

After 1477, the Ming government reversed its open maritime policies, enacting a series of isolationist policies in response to piracy. The policies, called Haijin (sea ban), lasted until the end of the Ming dynasty in 1644. During this period, Chinese navigation technology did not make any progress and even declined in some aspect.[27]

Early modern

With the development of the carrack, the west moved into a new era of ship construction by building the first regular oceangoing vessels. In a relatively short time, these ships grew to an unprecedented size, complexity and cost.

Shipyards became large industrial complexes and the ships built were financed by consortia of investors. These considerations led to the documentation of design and construction practices in what had previously been a secretive trade run by master shipwrights, and ultimately led to the field of naval architecture, where professional designers and draftsmen played an increasingly important role.[32] Even so, construction techniques changed only very gradually. The ships of the Napoleonic Wars were still built more or less to the same basic plan as those of the Spanish Armada of two centuries earlier but there had been numerous subtle improvements in ship design and construction throughout this period. For instance, the introduction of tumblehome; adjustments to the shapes of sails and hulls; the introduction of the wheel; the introduction of hardened copper fastenings below the waterline; the introduction of copper sheathing as a deterrent to shipworm and fouling; etc.[33]

Industrial Revolution

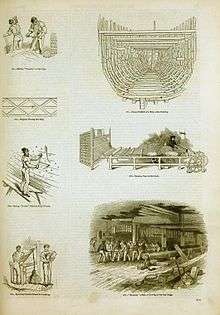

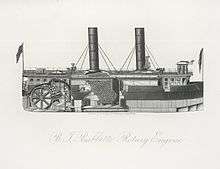

The industrial revolution made possible the use of new materials and designs that radically altered shipbuilding. Iron was gradually adopted in ship construction, initially in discrete areas in a wooden hull needing greater strength, (e.g. as deck knees, hanging knees, knee riders and the other sharp joints, ones in which a curved, progressive joint could not be achieved). Then, in the form of plates riveted together and made watertight, it was used to form the hull itself.

Sailing ship technology vastly improved during the early Industrial Revolution (between 1760 and 1825), as "the risk of being wrecked for Atlantic shipping fell by one third, and of foundering by two thirds, reflecting improvements in seaworthiness and navigation respectively."[34] The improvements in seaworthiness have been credited to "replacing the traditional stepped deck ship with stronger flushed decked ones derived from Indian designs, and the increasing use of iron reinforcement."[34] The design originated from Bengal rice ships,[34] with Bengal being famous for its shipbuilding industry at the time.[35] One study finds that there were considerable improvements in ship speed from 1750 to 1850: "we find that average sailing speeds of British ships in moderate to strong winds rose by nearly a third. Driving this steady progress seems to be continuous evolution of sails and rigging, and improved hulls that allowed a greater area of sail to be set safely in a given wind. By contrast, looking at every voyage between the Netherlands and East Indies undertaken by the Dutch East India Company from 1595 to 1795, we find that journey time fell only by 10 per cent, with no improvement in the heavy mortality, averaging six per cent per voyage, of those aboard."[36]

Initially copying wooden construction traditions with a frame over which the hull was fastened, Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Great Britain of 1843 was the first radical new design, being built entirely of wrought iron. Despite her success, and the great savings in cost and space provided by the iron hull, compared to a copper sheathed counterpart, there remained problems with fouling due to the adherence of weeds and barnacles. As a result, composite construction remained the dominant approach where fast ships were required, with wooden timbers laid over an iron frame (Cutty Sark is a famous example). Later Great Britain's iron hull was sheathed in wood to enable it to carry a copper-based sheathing. Brunel's Great Eastern represented the next great development in shipbuilding. Built in association with John Scott Russell, it used longitudinal stringers for strength, inner and outer hulls, and bulkheads to form multiple watertight compartments. Steel also supplanted wrought iron when it became readily available in the latter half of the 19th century, providing great savings when compared with iron in cost and weight. Wood continued to be favored for the decks.

During World War II, the need for cargo ships was so great that construction time for Liberty ships went from initially eight months or longer, down to weeks or even days. They employed production line and prefabrication techniques such as those used in shipyards today. The total number of dry-cargo ships built in the United States in a 15-year period just before the war was a grand total of two. During the war, thousands of Liberty ships and Victory ships were built, many of them in shipyards that didn't exist before the war. And, they were built by a workforce consisting largely of women and other inexperienced workers who had never seen a ship before (or even the ocean).[37][38][39]

Worldwide shipbuilding industry

After the Second World War, shipbuilding (which encompasses the shipyards, the marine equipment manufacturers, and many related service and knowledge providers) grew as an important and strategic industry in a number of countries around the world. This importance stems from:

- The large number of skilled workers required directly by the shipyard, along with supporting industries such as steel mills, railroads and engine manufacturers; and

- A nation's need to manufacture and repair its own navy and vessels that support its primary industries

Historically, the industry has suffered from the absence of global rules and a tendency towards (state-supported) over-investment due to the fact that shipyards offer a wide range of technologies, employ a significant number of workers, and generate income as the shipbuilding market is global.

Japan used shipbuilding in the 1950s and 1960s to rebuild its industrial structure; South Korea started to make shipbuilding a strategic industry in the 1970s, and China is now in the process of repeating these models with large state-supported investments in this industry. Conversely, Croatia is privatising its shipbuilding industry.

As a result, the world shipbuilding market suffers from over-capacities, depressed prices (although the industry experienced a price increase in the period 2003–2005 due to strong demand for new ships which was in excess of actual cost increases), low profit margins, trade distortions and widespread subsidisation. All efforts to address the problems in the OECD have so far failed, with the 1994 international shipbuilding agreement never entering into force and the 2003–2005 round of negotiations being paused in September 2005 after no agreement was possible. After numerous efforts to restart the negotiations these were formally terminated in December 2010. The OECD's Council Working Party on Shipbuilding (WP6) will continue its efforts to identify and progressively reduce factors that distort the shipbuilding market.

Where state subsidies have been removed and domestic industrial policies do not provide support in high labor cost countries, shipbuilding has gone into decline. The British shipbuilding industry is a prime example of this with its industries suffering badly from the 1960s. In the early 1970s British yards still had the capacity to build all types and sizes of merchant ships but today they have been reduced to a small number specialising in defence contracts, luxury yachts and repair work. Decline has also occurred in other European countries, although to some extent this has reduced by protective measures and industrial support policies. In the US, the Jones Act (which places restrictions on the ships that can be used for moving domestic cargoes) has meant that merchant shipbuilding has continued, albeit at a reduced rate, but such protection has failed to penalise shipbuilding inefficiencies. The consequence of this is that contract prices are far higher than those of any other country building oceangoing ships.

Present day shipbuilding

South Korea is the world's largest shipbuilder, followed by China.[40] South Korea's "big three" shipbuilders, Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, dominate the global market for large container ships.

The market share of European ship builders began to decline in the 1960s as they lost work to Japan in the same way Japan most recently lost their work to China and South Korea. Over the four years from 2007, the total number of employees in the European shipbuilding industry declined from 150,000 to 115,000.[41] The output of the United States also underwent a similar change.[42][43] Key shipbuilders in Europe are Fincantieri, Navantia, Naval Group and BAE Systems.

| Global Shipbuilding Industry | ||||

| Rank | Country | Completed Gross tonnage in 2018 (thousands)[40] | Market Share by New Orders in 2018[44] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49,600 | 40% | ||

| 2 | 43,900 | 36% | ||

| 3 | 13,005 | 7% | ||

| 4 | Others | 5,000 | 17% | |

Modern shipbuilding manufacturing techniques

Modern shipbuilding makes considerable use of prefabricated sections. Entire multi-deck segments of the hull or superstructure will be built elsewhere in the yard, transported to the building dock or slipway, then lifted into place. This is known as "block construction". The most modern shipyards pre-install equipment, pipes, electrical cables, and any other components within the blocks, to minimize the effort needed to assemble or install components deep within the hull once it is welded together.

Ship design work, also called naval architecture, may be conducted using a ship model basin. Previously, loftsmen at the mould lofts of shipyards were responsible for taking the dimensions, and details from drawings and plans and translating this information into templates, battens, ordinates, cutting sketches, profiles, margins and other data.[45] However, since the early 1970s computer-aided design became normal for the shipbuilding design and lofting process.[46]

Modern ships, since roughly 1940, have been produced almost exclusively of welded steel. Early welded steel ships used steels with inadequate fracture toughness, which resulted in some ships suffering catastrophic brittle fracture structural cracks (see problems of the Liberty ship). Since roughly 1950, specialized steels such as ABS Steels with good properties for ship construction have been used. Although it is commonly accepted that modern steel has eliminated brittle fracture in ships, some controversy still exists.[47] Brittle fracture of modern vessels continues to occur from time to time because grade A and grade B steel of unknown toughness or fracture appearance transition temperature (FATT) in ships' side shells can be less than adequate for all ambient conditions.[48]

Ship repair industry

All ships need repair work at some point in their working lives. A part of these jobs must be carried out under the supervision of the classification society.

A lot of maintenance is carried out while at sea or in port by ship's crew. However, a large number of repair and maintenance works can only be carried out while the ship is out of commercial operation, in a ship repair yard.

Prior to undergoing repairs, a tanker must dock at a deballasting station for completing the tank cleaning operations and pumping ashore its slops (dirty cleaning water and hydrocarbon residues).

See also

- List of shipbuilders and shipyards – Wikimedia list article

- List of the largest shipbuilding companies – Wikipedia list article

- List of Russian marine engineers – Wikimedia list article

- Marine propulsion – Systems for generating thrust for ships and boats on water

- Shipbuilding in the American colonies

References

- Ward, Cheryl. "World's Oldest Planked Boats", in Archaeology (Volume 54, Number 3, May/June 2009). Archaeological Institute of America.

- Schuster, Angela M.H. "This Old Boat", 11 December 2000. Archaeological Institute of America.

- Possehl, Gregory. Meluhha. in: J. Reade (ed.) The Indian Ocean in Antiquity. London: Kegan Paul Intl. 1996, 133–208

- (e.g. Lal 1997: 182–188)

- Tripathi, page 145

- Hourani & Carswel, page 90

- Robert E. Krebs, Carolyn A. Krebs (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Ancient World. Greenwood PressScience. ISBN 978-0-313-31342-4.

- Cottrell, Leonard. WarriorPharaohs. London: Evans Brothers Limited, 1968.

- L. Pham, Charlotte Minh-Hà (2012). Asian Shipbuilding Technology. Bangkok: UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education. p. 20. ISBN 978-92-9223-413-3.

- Maguin, Pierre-Yves (September 1980). "The Southeast Asian Ship: An Historical Approach". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 11 (2): 266–276. doi:10.1017/S002246340000446X. JSTOR 20070359.

- Casson, L. 1994. Ships and Seafaring in ancient times.

- Shaffer, Lynda Norene (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. M.E. Sharpe. Quoting Johnstone 1980: 191-192

- Robert, Dick-Read (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times. Thurlton.

- Christie, Anthony (1957). "An Obscure Passage from the "Periplus: ΚΟΛΑΝΔΙΟϕΩΝΤΑ ΤΑ ΜΕΓΙΣΤΑ"". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 19: 345–353 – via JSTOR.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 464.

- Reid, Anthony (2012). Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-9814311960.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves. 2012. “Asian ship-building traditions in the Indian Ocean at the dawn of European expansion”, in: Om Prakash and D. P. Chattopadhyaya (eds), History of science, philosophy, and culture in Indian Civilization, Volume III, part 7: The trading world of the Indian Ocean, 1500-1800, pp. 597-629. Delhi, Chennai, Chandigarh: Pearson.

- Rafiek, M. (December 2011). "Ships and Boats in the Story of King Banjar: Semantic Studies". Borneo Research Journal. 5: 187–200.

- Pham, Charlotte Minh-Hà L. (2012). "Unit 14: Asian Shipbuilding (Training Manual for the UNESCO Foundation Course on the protection and management of the Underwater Cultural Heritage)". Training Manual for the UNESCO Foundation Course on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage in Asia and the Pacificc. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-9223-414-0.

- Welsh, J. W. (2011, September 23). huge ancient Roman shipyard unearthed in Italy. Livescience. Retrieved from http://www.livescience.com/16201-rome-ancient-shipyard.html

- Zumerchik, John; Danver, Steven Laurence (2010). Seas and Waterways of the World: An Encyclopedia of History, Uses, and Issues. ABC-CLIO. pp. 428–. ISBN 978-1-85109-711-1.

- Haywood, John (1991). Dark Age Naval Power: Frankish & Anglo-Saxon Seafaring Activity. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-0415063746.

NB second edition 2006: 978-1898281436

- "Sutton Hoo ship burial". Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- "Round ship". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "Michael of Rhodes: A medieval mariner and his manuscript". Meseo Galileo. Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology. 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Pamela O. Long, David McGee, and Allan M. Stahl, eds. The Book of Michael of Rhodes: A Fifteenth-Century Maritime Manuscript, 3 vols. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009)

- Clunas, Craig; Sally K. Church. Harrison Hall, Jessica (ed.). Ming China: Courts and Contacts 1400-1450. The British Museum, Great Russel Street, London WCIB 3DG. pp. Chapter 22.

- Levathes, Louise (2014-12-02). When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781504007368.

- Finlay, Robert (1995). "The Treasure-Ships of Zheng He: Chinese Maritime Imperialism in the Age of Discovery". In Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (ed.). The Global Opportunity. 1. Aldershot: Ashgate Variorum. p. 96.

- Chen, Zhongping (2017). Zou xiang duo yuan wen hua de quan qiu shi: Zheng He xia xi yang (1405-1433) Ji zhong guo yu yin du yang shi jie de guan xi 走向多元文化的全球史:鄭和下西洋(1405-1433)及中國與印度洋世界的關系 [Toward a multicultural global history: Zheng He's voyages to the Western seas (1405-1433) and the relationship between China and the Indian Ocean region] (in Chinese) (First ed.). Beijing: SDX Joint Company. p. 497.

- Chan, Alan Kam-leung, et al. Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine. VII, World Scientific, Singapore University Press, 2003. p. 107

- Tipping, Colin (November 1998). "Technical Change and the Ship Draughtsman". The Mariner's Mirror. 84 (4): 458 foll. doi:10.1080/00253359.1998.10656717.

- Mccarthy, Michael (2005). Ships' Fastenings: From Sewn Boat to Steamship. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-621-1.

- "Technological Dynamism in a Stagnant Sector: Safety at Sea during the Early Industrial Revolution" (PDF).

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 178, 186–188. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Kelly, Morgan; ó Gráda, Cormac (2017). "Speed under Sail, 1750–1830". Working Papers 201710. School of Economics, University College Dublin.

- Sawyer, L.A. and Mitchell, W. H. The Liberty Ships: The History of the "Emergency" Type Cargo Ships Constructed in the United States During the Second World War, pp. 7–10, 2nd Edition, Lloyd's of London Press Ltd., London, England, 1985. ISBN 1-85044-049-2.

- Jaffee, Capt. Walter W. The Lane Victory: The Last Victory Ship in War and Peace, pp. 4–9, 15–32, 2nd Edition, Glencannon Press, Palo Alto, California, 1997. ISBN 0-9637586-9-1.

- Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 135–6, 178–80, Random House, New York, NY, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- "Largest shipbuilding nations based on gross tonnage 2018 - Ranking". Statista.

- Zagreb Institute of Public Finance, Newsletter No. 64, December 2011, ISSN 1333-4263

- James Brooke (2005-01-06). "Korea reigns in shipbuilding, for now". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "기획특집/ 1등 조선.해양 한국에 도전하는 해외 국가별 조선산업 현황: 1)일본, 중국, 인도, 베트남, 브라질, 폴란드, 터키, 독일 조선산업의 현황과 전망/(월간 해양과조선 2008년 11월호)". Shipbuilding.or.kr. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- "Global shipbuilding market by region: contracting 2018 - Statistic". Statista.

- "The Mould Loft". The Loftsman. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- "CAD-Computer Aided Design". The Loftsman. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Drouin, P: "Brittle Fracture in ships – a lingering problem", page 229. Ships and Offshore Structures, Woodhead Publishing, 2006.

- "Marine Investigation Report – Hull Fracture Bulk Carrier Lake Carling". Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 19 March 2002. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

Notes

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1967). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 145. ISBN 81-208-0018-4.

- Hourani, George Fadlo; Carswel, John (1995). Arab Seafaring: In the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times. Princeton University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-691-00032-8.

External links

- Shipbuilding Picture Dictionary

- U.S. Shipbuilding—extensive information about the U.S. shipbuilding industry, including over 500 pages of U.S. shipyard construction records

- Shipyards United States—from GlobalSecurity.org

- Shipbuilding News

- Bataviawerf – the Historic Dutch East Indiaman Ship Yard—Shipyard of the historic ships Batavia and Zeven Provincien in the Netherlands, since 1985 here have been great ships reconstructed using old construction methods.

- Photos of the reconstruction of the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia—Photo web site about the reconstruction of the Batavia on the shipyard Batavia werf, a 16th-century East Indiaman in the Netherlands. The site is constantly expanding with more historic images as in 2010 the shipyard celebrates its 25th year.