Radio City Music Hall

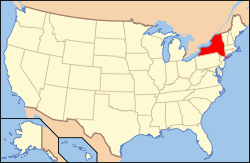

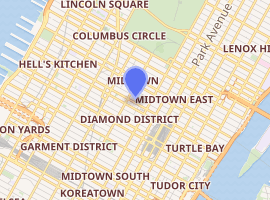

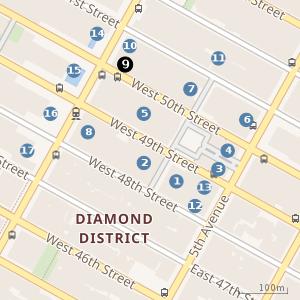

Radio City Music Hall is an entertainment venue at 1260 Avenue of the Americas, within Rockefeller Center, in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. Nicknamed the Showplace of the Nation, it is the headquarters for the Rockettes, the precision dance company.

Radio City Music Hall in 2010 | |

| |

| Location | 1260 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue), Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′35″N 73°58′45″W |

| Owner | Tishman Speyer Properties (operated by The Madison Square Garden Company)[1] |

| Type | Indoor theatre |

| Seating type | Reserved |

| Capacity | 5,960 |

Radio City Music Hall | |

| Area | 2 acres (0.8 ha) |

| Architect | Edward Durell Stone Donald Deskey |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| Part of | Rockefeller Center (ID87002591) |

| NRHP reference No. | 78001880[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 8, 1978 |

| Designated NYCL | March 28, 1978[3] |

| Opened | December 27, 1932 |

Radio City Music Hall was built on a plot of land that was originally intended for a Metropolitan Opera House. The opera house plans were canceled in 1929, leading to the construction of Rockefeller Center.

Radio City Music Hall was designed by Edward Durell Stone and Donald Deskey in the Art Deco style. One of the more notable parts of the Music Hall is its large auditorium, which was the world's largest when the Hall first opened. The new complex included two theaters, the "International Music Hall" and the Center Theatre, as part of the "Radio City" portion of Rockefeller Center. The 5,960-seat Music Hall was the larger of the two venues. It was largely successful until the 1970s, when declining patronage nearly drove the Music Hall to bankruptcy. Radio City Music Hall was designated a New York City Landmark in May 1978, and the Music Hall was restored and allowed to remain open. The hall was extensively renovated in 1999.

The Music Hall also contains a variety of art. Although Radio City Music Hall was initially intended to host stage shows, it hosted performances in a film-and-stage-spectacle format through the 1970s, and was the site of several movie premieres. It now primarily hosts concerts, including by leading pop and rock musicians, and live stage shows such as the Radio City Christmas Spectacular. The Music Hall has also hosted televised events including the Grammy Awards, the Tony Awards, the Daytime Emmy Awards, the MTV Video Music Awards, and the NFL Draft.

History

| Buildings of Rockefeller Center |

|

Buildings and structures in Rockefeller Center: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

Planning

The construction of Rockefeller Center occurred between 1932 and 1940[6] on land that John D. Rockefeller Jr. leased from Columbia University.[7] The Rockefeller Center site was originally supposed to be occupied by a new opera house for the Metropolitan Opera.[8] By 1928, Benjamin Wistar Morris and designer Joseph Urban were hired to come up with blueprints for the house.[9] However, the new building was too expensive for the opera to fund by itself, and it needed an endowment,[10] and the project ultimately gained the support of John D. Rockefeller Jr.[10][11] The planned opera house was canceled in December 1929 due to various issues,[12][13][14] but Rockefeller made a deal with RCA to develop Rockefeller Center as a mass media complex with four theaters.[15][16] This was later downsized to two theaters.[17][18]

Samuel Roxy Rothafel, a successful theater operator who was renowned for his domination of the city's movie theater industry,[19] joined the center's advisory board in 1930.[20][21][22] He offered to build two theaters: a large vaudeville "International Music Hall" on the northernmost block with more than 6,200 seats, and the smaller 3,500-seat "RKO Roxy" movie theater on the southernmost block.[21][23] The idea for these theaters was inspired by Roxy's failed expansion of the 5,920-seat Roxy Theatre on 50th Street, one and a half blocks away.[24][25][26] Roxy also envisioned an elevated promenade between the two theaters,[27] but this was never published in any of the official blueprints.[21]

In September 1931, a group of NBC managers and architects went to tour Europe to find performers and look at theater designs.[28][29] However, the group did not find any significant architectural details that they could use in the Radio City theaters.[30] In any case, Roxy's friend Peter Clark turned out to have much more innovative designs for the proposed theaters than the Europeans did.[31]

Roxy had a list of design requests for the Music Hall.[32][33] First, he did not want the hall to have either a large balcony over the box seating, or rows of box seating facing each other, as implemented in opera houses. This resulted in a "tiered" balcony system where several shallow balconies were built at the back of the theater, cantilevered off the back wall.[34] Second, Roxy specified that the stage contain a central section with three parts, so that the sets could be changed easily.[35] Roxy also wanted red seats because he believed it would make the theater successful.[34] He wished for an auditorium with an oval shape because contemporary wisdom held that oval-shaped auditoriums had better acoustic qualities.[32][36] Finally, he wanted to build at least 6,201 seats in the Music Hall so it would be larger than the Roxy Theatre. There were only 5,960 audience seats, but Roxy counted exactly 6,201 seats by including elevator stools, orchestra pit seats, and dressing-room chairs.[33]

Despite Roxy's specific requests for design features, the Music Hall's general design was determined by the Associated Architects, the architectural consortium that was designing the rest of Rockefeller Center.[35] The Radio City Music Hall was designed by architect Edward Durell Stone[37] and interior designer Donald Deskey[38] in the Art Deco style.[39] Stone used Indiana Limestone for the facade, as with all the other buildings in Rockefeller Center, but he also included some distinguishing features. Three 90-foot-tall (27 m) signs with the hall's name on it were placed on the facade, while intricately ornamented fire escapes were installed on the walls facing 50th and 51st Streets. Inside, Stone designed 165-foot-long (50 m) Grand Foyer with a large staircase, balconies, and mirrors, and commissioned Ezra Winter for the grand foyer's 2,400-square-foot (220 m2) mural, "Quest for the Fountain of Eternal Youth".[40][36] Deskey, meanwhile, was selected as part of a competition for interior designers for the Music Hall.[41] He had reportedly called Winter's painting "God-awful" and regarded the interior and exterior as not much better.[40] To make the Music Hall presentable in his opinion, Deskey designed upholstery and furniture that was custom to the Hall. Deskey's plan was regarded the best of 35 submissions, and he ultimately used the rococo style in his interior design.[42]

The International Music Hall later became the Radio City Music Hall.[43] The names "Radio City" and "Radio City Music Hall" derive from one of the complex's first tenants, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), who planned a mass media complex called Radio City on the west side of Rockefeller Center.[44]

Construction, opening, and early years

Construction on Radio City Music Hall started in December 1931,[45] and the hall topped out in August 1932.[46] Its construction set many records at the time, including the use of 15,000 miles (24,000 km) of copper wire and 200 miles (320 km) of brass pipe.[47] In November 1932, Russell Markert's précision dance troupe the Roxyettes (later to be known as the Rockettes) left the Roxy Theatre and announced that they would be moving to the Music Hall. By then, Roxy was busy adding music acts in preparation for the hall's opening at the end of the year.[48][49]

The Music Hall opened to the public on December 27, 1932, with a lavish stage show featuring numbers including Ray Bolger, Doc Rockwell and Martha Graham.[32][50] The opening was meant to be a return to high-class variety entertainment.[51][52] However, the opening was not a success: the program was very long, spanning from 8 p.m. to 2 a.m. of the next day, and a multitude of acts were crammed onto the world's largest stage, ensuring that individual acts were lost in the cavernous hall. As the premiere went on, audience members, including John Rockefeller Jr, waited in the lobby or simply left early.[32][53] Some news reporters, tasked with writing reviews of the premiere, guessed the ending of the program because they left beforehand.[54] Reviews ranged from furious to commiserate.[55] The film historian Terry Ramsaye wrote that "if the seating capacity of the Radio City Music Hall is precisely 6,200, then just exactly 6,199 persons must have been aware at the initial performance that they were eye witnesses to [...] the unveiling of the world's best 'bust'".[56] Set designer Robert Edmond Jones resigned in disappointment, and Graham was fired.[55] Despite the negative reviews of the performances, the theater's design was very well received.[57] One reviewer stated: "It has been said of the new Music Hall that it needs no performers; that its beauty and comforts alone are sufficient to gratify the greediest of playgoers."[58]

On January 11, 1933, after incurring a net operating loss of $180,000, the Music Hall converted to the then-familiar format of a feature film, with a spectacular stage show that Roxy had perfected.[59][60] The first film shown on the giant screen was Frank Capra's The Bitter Tea of General Yen,[59][61] and the Music Hall became the premiere showcase for films from the RKO-Radio Studio, with Topaze the first RKO film to play there.[62] The film-plus-stage-spectacle format continued at the Music Hall until April 25, 1979, with four complete performances presented every day;[63] the final film the Music Hall presented under this format was The Promise (1979).[64] Some of the films that premiered at Radio City Music Hall included King Kong (1933), Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Mary Poppins (1964), and The Lion King (1994).[65] In total, over 650 movies are said to have premiered at the Music Hall.[66] The hall was also used for other purposes; for instance, it was used to host Easter worship services starting in 1940,[67] as well as benefit parties for Big Brothers Inc. from 1953[68] to at least 1959.[69]

Decline

Through the 1960s, the Music Hall was successful regardless of the status of the city's economic, business, or entertainment sectors as a whole. It remained open even as other theaters such as the Paramount and the Roxy closed.[70][71] Even so, officials had intended to close down Radio City Music Hall in 1962, in what would become one of several such unheeded announcements.[72] By 1964, the Radio City Music Hall was projected to have 5.7 million annual visitors, who paid ticket prices of between 99 cents and $2.75 (equivalent to between $8 and $23 in 2019).[71] The hall had evolved to show fewer adult films, instead choosing to show films for general audiences.[71][66] However, the Music Hall's operating costs were almost twice as high as those of smaller performance venues. In addition, with the loosening of regulations on explicit content, the Music Hall's audience was mostly relegated to families.[66]

Radio City Music Hall was closed entirely for five days in early 1965 for its first-ever full cleaning, which included changing the curtains and painting the ceiling.[70][73] Repairs were also performed on the hall's organs during the nighttime.[74]

By the early 1970s, the proliferation of closed-captioned foreign movies had reduced attendance at the Music Hall.[70] Changes in film distribution made it difficult for Radio City Music Hall to secure exclusive bookings of many films, and the Music Hall preferred to show only G-rated movies, which further limited their film choices as the decade wore on.[75] Popular films, such as Chinatown, Blazing Saddles, and The Godfather Part II, failed the Music Hall's screening criteria.[70] By 1972, the Music Hall had fired the performers' unions as well as six of the thirty-six Rockettes. A painting by Stuart Davis was donated to the Museum of Modern Art to reduce Radio City Music Hall's tax burden.[76] In 1977, annual attendance reached an all-time low of 1.5 million,[77] a 70% decrease from the 5 million visitors reported in 1968.[78][79]

Bankruptcy and threat of closure

By January 1978, the Music Hall was in debt,[80][81] and officials stated that it could not remain open after April.[80] Alton Marshall, president of Rockefeller Center, announced that due to a projected loss of $3.5 million for the upcoming year Radio City Music Hall would close its doors on April 12.[72][82] Plans for alternate uses for the structure included converting the theater into tennis courts, a shopping mall, an aquarium, a hotel, a theme park, or the American Stock Exchange.[83][77] Upon hearing the announcement, Rosemary Novellino, Dance Captain of the Radio City Music Hall Ballet Company, formed the Showpeople's Committee to Save Radio City Music Hall. The Committee consisted of an alliance between performers, the media, and political allies including New York lieutenant governor Mary Anne Krupsak.[84] The public also made hundreds of calls to Rockefeller Center, and The New York Times described that the callers "jammed the switchboards" there.[85] The Rockettes also protested outside New York City Hall.[79]

Following the closure announcement, the interior was made a city landmark on March 29.[86][87] This designation was contested, and Rockefeller Center Inc. unsuccessfully filed a lawsuit to try to reverse the landmark designation.[88][77] On April 8, four days before the planned closing date, the Empire State Development Corporation voted to create a nonprofit subsidiary to lease the Music Hall.[89] One month later, on May 12, Radio City Music Hall was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[90]

Plans for a 20-story mixed-use tower above the Radio City Music Hall were announced in April 1978, with rents from the proposed tower providing the necessary funds to keep the hall open.[81] An alternative involving transferring the hall's air rights to another building in the complex was also privately discussed.[91] The office building plans were recommended in a draft study that was published in February 1979.[92] The office building was ultimately not built, and Rockefeller Center Inc. instead decided to restore Radio City Music Hall to its original condition.[78] The renovation of the Music Hall started in April 1979.[93] In 1980, the hall reopened to the public. Regular film showings at Radio City ended, and live shows were cut back to holiday showings only.[77] Around this time, the Music Hall started creating its own music concerts. Prior to the reopening, the Music Hall was rented to music concerts, but had never hosted a concert that it created.[94]

Late 20th century

After its near-closure and subsequent reopening, Radio City Music Hall diversified its selection of shows and performances.[94] Time slots were set aside for movie screenings, but the Music Hall had mostly turned to stage shows.[66] By January 1980, the Music Hall was hosting shows such as the stage adaptation of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the Rockettes Spectacular.[95] However, the theatrical shows proved to be unpopular, so in 1983, the Radio City Music Hall shifted to creating music concerts and participating in the production of films and TV shows.[96] The parent company, Radio City Music Hall Productions (a subsidiary of Rockefeller Center Inc.), started creating or co-creating films and Broadway shows such as Legs and Brighton Beach Memoirs.[94] In 1985, Radio City Music Hall finally recorded its first profit in three decades, with a net gain of $2.5 million that year. This was partly attributed to the addition of music concerts, which appealed toward younger viewers.[94] The Music Hall also started hosting televised events including the Grammy Awards, the Tony Awards, the Daytime Emmy Awards, the MTV Video Music Awards, and the NFL Draft.[65][lower-alpha 1]

A new golden curtain was installed at the main stage in January 1987. The curtain was the third one to be installed since the Music Hall's opening in 1932; it had last been replaced in 1965. Because of the Radio City Music Hall's historic status, the curtain had to be the same style, texture, and color as the previous curtains.[97]

In 1997, Radio City Music Hall was leased to the Madison Square Garden Company (then known as Cablevision). This move provided funding to keep the Rockettes and the Christmas Spectacular at the Music Hall; in addition, Cablevision would be able to renovate and manage the hall.[98] Radio City Music Hall was closed on February 16, 1999,[99] for a comprehensive renovation.[63][100] During the closure, many components were cleaned and modernized. The curtains were replaced, seats were reupholstered, carpets were relaid, and doorknobs and light fixtures were replaced.[100] The renovation was originally projected to cost $25 million, but later increased to $70 million due to various additional tasks that surfaced during the extensive refurbishment.[101] The Music Hall received a $2.5 million tax break from the Empire State Development Corporation, which was meant to accommodate the expenditure of up to $66 million in renovation costs.[102] The hall reopened with a gala concert on October 5, 1999.[103]

Early 21st century

In 2017, the Music Hall's Rockettes faced some controversy when it was announced they would perform at the inauguration of Donald Trump as President of the United States.[104][105] The announcement prompted calls on social media for boycotts of the Rockettes and the Music Hall.[106]

In March 2020, Radio City Music Hall announced a decision to remain open on March 12 and 13, which was controversial in light of the ban on gatherings of 500 or more in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City.[107] This decision stood in contrast to many other venues and public events in New York City, which had shut down;[108] the city's mayor Bill de Blasio had previously stated that venues such as Radio City Music Hall could potentially be shut down for several months.[109] Radio City Music Hall later decided to remain closed after March 13, with no set reopening date, since other venues had also closed indefinitely. This affected events like the 74th Tony Awards, originally scheduled for June 7 but was then postponed after the Music Hall's closure.[110][111]

Design

Exterior

Radio City Music Hall is located on the east side of Sixth Avenue between 50th and 51st Streets.[112] Located in a niche under the neighboring 1270 Avenue of the Americas, the Music Hall is housed under the building's first setback on the seventh floor.[113]

Its exterior is notable for a long marquee sign that wraps around the corner of Sixth Avenue and 50th Street, as well as narrower, seven-story-high signs on the north and south ends of the marquee's Sixth Avenue side; both signs display the hall's name in neon letters.[113] The main entrance to the Music Hall was placed at the corner of Sixth Avenue and 50th Street, underneath the marquee. The entrance's location, which was enhanced by the amount of open space in front of that corner, ensured that the hall could easily be seen from the Broadway theater district a block to the west. An entrance to the New York City Subway's 47th–50th Streets–Rockefeller Center station, served by the B, D, F, <F>, and M trains, is located on Sixth Avenue directly adjacent to the north end of the marquee, within the same structure that houses Radio City Music Hall.[36]

The hall's exterior also has visual features signifying the building's purpose. Above the entrance, Hildreth Meiere created six small bronze plaques of musicians playing different instruments, as well as three larger metal and enamel plaques signifying dance, drama, and song; these plaques denote the theater's theme.[114][115][116] At one point, a tennis court was located on the theater's rooftop garden.[117]

Interior

The interior contains a "majestic" grand foyer, the large and lavishly decorated main auditorium, and a series of stairs and elevators that lead to levels of mezzanines.[118][119][120] Designed by Edward Durell Stone,[37] the interior of the theater with its austere Art Deco lines represented a break with the traditional ornate rococo ornament associated with movie palaces at the time.[38] Donald Deskey coordinated the interior design process, as well as designed some of the wallpaper, furniture, and other decor in the Music Hall.[38] Deskey's geometric Art Deco designs incorporate glass, aluminum, chrome, and leather in the ornament for the theater's wall coverings, carpet, light fixtures, and furniture.[121] All of the Music Hall's staircases were fitted with brass railings, an aspect of the Art Deco style.[122]

Deskey commissioned textile designers Marguerita Mergentime and Ruth Reeves to create carpet designs and designs for the fabrics covering the walls.[121][114] Reeves designed a carpet that contained musical motifs in "shades of red, brown, gold, and black",[122] but her design was replaced in 1999.[123] Mergentime also produced geometric designs of nature and musicians for the walls and carpets, which still exist.[124] Deskey also created his own carpet design consisting of "singing head" depictions, which still exists.[125] Rene Chambellan produced six "playful" bronze plaques of vaudeville characters, which are located in the lobby just above the entrances to the theater.[126] Henry Varnum Poor designed all of the Music Hall's ceramic fixtures, especially the lighting bases.[127]

Lobbies and grand foyer

The entrance to the Music Hall is at its southwestern corner, where there are adjacent ticket and advance sales lobbies. Both lobbies contain terrazzo floors and marble walls. The ticket lobby, accessible from Sixth Avenue between 50th and 51st Streets, is the larger of the two lobbies. There are four brass ticket booths: one each embedded into the northern and southern walls, and two in the middle, facing the booths in the walls. Large black pillars support a low, slightly coffered ceiling.[128] Circular light fixtures are set into the ceiling of the ticket lobby, within each of the slight indentations.[129] The advance sales lobby, accessible from 50th Street just east of Sixth Avenue, contains a single ticket booth on the eastern wall.[128]

To the ticket lobby's east, and the advance sales lobby's northeast, is the elliptical grand foyer, whose four-story-high ceiling and dramatic artwork contrast with the compactness of the lobby.[122] Two long, tubular chandeliers created by Edward F. Caldwell & Co. hang from the ceiling.[122][130] The northern side of the grand foyer contains Ezra Winter's mural, and a grand staircase leading up to the first-mezzanine foyer runs along the northern wall next to Winter's mural.[114][131] Another set of stairs below the grand staircase descends from the northern side of the foyer to the main lounge one level below.[132] A smaller staircase to the first-mezzanine lounge runs along the southern wall, connecting to a curved extension of that level's balcony.[133] The southern and northern sides of the grand foyer, respectively leading to 50th and 51st Streets, contain shallow vestibules with red marble walls. The northern vestibule is used as the exit lobby, while the southern vestibule is an emergency exit.[128] The grand foyer's eastern wall contains openings from the first, second, and third mezzanine levels, and the western wall contains 50-foot-tall (15 m) mirrors within gold frames.[122] Eleven doors leading to the Music Hall's auditorium are also located on the grand foyer's eastern side.[132] Chambellan commissioned several plaques on the auditorium doors' exteriors, which resemble the vaudeville representations in the lobby and depict the types of performances in the Music Hall.[134][132]

The Music Hall includes four elevators that serve the main lounge level through the third mezzanine level. At ground level, a marble lobby for these elevators is located to the west of the northern exit vestibule.[128] Chambellan also designed the elevator doors with reliefs of musicians in atypical representations.[135][128] The maple circular roundels inside the cabs were designed by Edward Trumbull, and represent wine, women, and song.[124][128]

Auditorium

The auditorium itself is very large and striking. Architectural critic Douglas Haskell describes it thus: "The focus is the great proscenium arch, over 60 feet [18 m] high and 100 feet [30 m] feet wide, a huge semi-circular void. From that the energy disperses, like a firmament the arched structure rises outward and forward. The 'ceiling', uniting sides and top in its one great curve, proceeds by successive broad bands, like the bands of northern lights."[36] In the hall's early years, the Federal Writer's Project noted that "nearly everything about the Music Hall is tremendous", with the hall hosting the world's largest orchestra; most expansive theater screen; heaviest proscenium arch used in a theater; and "finest precision dancers", the Rockettes.[119]

The auditorium has around 5,960 seats for spectators.[34] Around 3,500 of these seats are located in the orchestra seating area on ground level, while the remaining seats are distributed among the three mezzanine levels (see § Mezzanines). The orchestra and mezzanine sections all contain reddish-brown plush seating throughout, as well as storage compartments under each seat, lights at the end of each row of seats, and more legroom space than in other theaters.[132]

The auditorium's ceiling is ringed with eight telescoping bands, the "northern lights" Haskell described.[132] Each of the bands' edges contain a 2-foot (0.61 m) overlap with each other. In Joseph Urban's original plans, the ceiling was to be coffered, but after the cancellation of the Opera House, designers proposed many different designs for the proposed Music Hall's ceiling. The current design was put forth by Raymond Hood, who incidentally derived his band-system idea from a book that Urban had written.[36] The walls are covered by intricate fabric silhouette patterns of performers and horses, which were created by Reeves.[136] The radiating arches of the proscenium unite the large auditorium, allowing a sense of intimacy as well as grandeur. The ceiling arches also contain grilles that camouflage the air conditioning and the auditorium's sound system.[132]

The Great Stage, designed by Peter Clark, measures 66.5 by 144 ft (20.3 by 43.9 m) and resembles a setting sun.[137][31] Roxy reportedly envisioned the sunset design of the stage while traveling home from Europe on an ocean liner.[138] There are two stage curtains; the main one is made of steel and asbestos, which can part horizontally, while the plush curtain behind it has several horizontal sections that can be raised or lowered independently of each other. The center of the stage consists of a rotating section of floor with a 50-foot (15 m) diameter.[132] The orchestra pit, which could fit 75 musicians, was placed on a "bandwagon" that could move vertically or longitudinally relative to the stage.[59]

There is a complicated system of indirect cove lighting at the front of the stage, facing toward the audience. When the Music Hall was first opened, it was equipped with all of the newest lighting innovations at the time, including lights that changed colors automatically and adjusted their own brightness based on different lighting levels in the theater.[36]

Mezzanines

The Music Hall contains three mezzanines within the back wall of the auditorium,[139] as well as a main lounge in the basement.[132] Each of the mezzanines is shallow, and all three mezzanine levels are stacked on top of the orchestra's rear seats. Ramps on either side of the stage lead to the first mezzanine level, the lowest of the three mezzanines, creating the impression of a stage encircling the orchestra.[35] Each of the three mezzanine levels has a men's smoking room, a women's lounge, and men's and women's restrooms. No two restrooms or lounges have the same design.[133] A 1932 New York Times article described the reasons for such varied designs: "Since the auditoriums, men's lobbies, smoking rooms and women's lounges are used for a few hours only, decorative schemes are appropriate in them that would be too dramatic for a home."[114]

Main lounge

The main lounge in the basement is decorated with a design rivaling the grand foyer above it. The walls are composed of black "permatex", which was a new material at the time of the Music Hall's construction. The ceiling has diamond-shaped light fixtures and is supported by six diamond-shaped piers, as well as three full-height piers of a similar shape that exist only for aesthetic purposes.[132] The lounge is decorated with several artworks (see § Art).[140] Deskey also designed the chrome furniture and the carpeting of the lounge.[127]

The landing for the Music Hall's elevator bank is located on the northern side of the main lounge. A marble wall with three large columns comprises the western side of the lounge. A hallway extends off the eastern side of the lounge and leads to a men's smoking room and a women's lounge, which both connect to restrooms of their respective genders.[127] The smoking room has a masculine theme with terrazzo floors, brown walls, and copper ceilings. The accompanying men's restroom has black-and-white tiles and simple geometric fixtures, which are duplicated in the men's restrooms on each mezzanine level.[141] The women's lounge is mostly designed with the same soft colors as Witold Gordon's "History of Cosmetics Mural", located on the room's walls, although the wall area not covered by the mural is painted beige. The attached women's restroom is similar to the men's restroom on the same floor but contains vertical cylindrical lighting, stools, and circular mirrors above aqua sinks.[133]

Offstage

The offstage area of the Music Hall contains many rooms that allow all productions to be prepared on-site. The offstage rooms include a carpenter's studio, a scene shop, sewing rooms, dressing rooms for 600 people, a green room for performers' guests, and a dormitory.[36][142]

The elevator system was designed by Peter Clark and built by Otis Elevators. The elevator system was so advanced that the U.S. Navy incorporated identical hydraulics in constructing World War II aircraft carriers; according to Radio City lore, during the war, government agents guarded the basement to hide the U.S. Navy's technological advantage.[143]

Art

The public areas of the Music Hall feature the work of many Depression-era artists, who were commissioned by Deskey as part of his general design scheme.[144] The large 2,400-square-foot (220 m2) mural in the grand foyer, "Quest for the Fountain of Eternal Youth", was painted by Ezra Winter and depicts a fable from a Native American tribe in Oregon.[144][145] The murals on the wall of the grand lounge, which depict five eras of differing theater scenes, are collectively known as the "Phantasmagoria of the Theater" by Louis Bouche.[144][114][146][132][147] Three female nudes cast in aluminum were commissioned for the music hall, but Roxy thought that they were inappropriate for a family venue.[148] Although the Rockefellers loved the sculptures, the only one that was displayed on opening night was "Goose Girl" by Robert Laurent, which is located on the first mezzanine and depicts a nude aluminum girl beside a slender aluminum goose.[149] Since opening night the other two sculptures have been put on display at the Music Hall. "Eve" by Gwen Lux is displayed in the southwest corner of the grand foyer,[150][146] and "Spirit of the Dance" by William Zorach is visible from the grand lounge.[151][127][144][146]

Each of the public restrooms have adjoining lounges that display various works of art.[152] The third-floor women's restroom contains the Panther Mural by Henry Billings, which is accompanied by Deskey's abstract wall coverings in the women's lounge.[114][153] The women's lounge on the second mezzanine houses Yasuo Kuniyoshi's oil painting of "larger-than-life botanical designs" along the entire wall,[114][154] which had originally been commissioned by Georgia O'Keeffe before she suffered a nervous breakdown and left the mural incomplete.[154][155] Deskey created a wall covering for the men's lounge on the second mezzanine, containing masculine icons and nicotine motifs.[156] He also designed the first-mezzanine women's lounge, a room full of mirrors with a blue-and-white carpet and frosted low-intensity lights.[157] Witold Gordon painted a map with caricatures and stereotypical motifs in the men's lounge on the same floor,[114][158] as well as a "History of Cosmetics Mural" in the women's lounge in the basement.[114][133][159] Stuart Davis created Men Without Women, a mural of masculine stereotypical pastimes in the basement-level men's lounge;[114][127][160][lower-alpha 2] the work was donated to the Museum of Modern Art in 1975[77][162] and loaned back to the Music Hall in 1999.[160] Finally, Edward Buk Ulreich created a "Wild West Mural" on the third-mezzanine men's lounge.[144][114][163]

Usage

Concerts

Pink Floyd played at the Music Hall on March 17, 1973.[164] The Grateful Dead played eight shows over 9 days in October 1980, culminating on Halloween; two of the shows from this run were released as the video Grateful Dead: Dead Ahead.[165] American new wave band Devo performed at Radio City Music Hall on October 31, 1981 during their New Traditionalists tour.[166][167] In the 1980s, Liberace grossed $2.5 million from fourteen performances with a combined audience of 82,000, setting a box-office record for Radio City Music Hall at the time.[168]

Lady Gaga and Tony Bennett performed at the Music Hall as part of their Cheek to Cheek Tour on June 19–23, 2015.[169] In addition, Britney Spears performed at the Hall for two sold-out shows as part of her Piece of Me Tour on July 23 and 24, 2018.[170] Christina Aguilera performed there for two sold out nights as part of the Liberation tour on October 3 and 4, 2018.[171] Mariah Carey performed to a sold-out crowd as part of her Caution World Tour on March 25, 2019.[172][173]

Shows

The Radio City Christmas Spectacular is an annual Christmas stage musical produced by MSG Entertainment, which operates the Music Hall. A New York Christmas tradition since 1933,[174] it features the women's precision dance team known as the Rockettes.[175]

The Irish dance show Riverdance made its North American debut at the Music Hall in March 1996, breaking box-office records.[176][177] Radio City Music Hall also hosted the Cirque du Soleil show "Zarkana" from June 2011[178] to September 2012.[179]

Television

Radio City Music Hall has been used for televised game shows such as Hollywood Squares, Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy!. For two weeks in November 1988, the theater hosted Wheel of Fortune, which was taking its first road trip. Saturday Night Live announcer Don Pardo announced during the two weeks.[180] It played host to the show again in November 2003 for the nighttime show's 4,000th episode,[181] and again in November 2007 for the nighttime show's 25th anniversary.[180] Radio City Music Hall was also the site for Jeopardy!'s four-thousandth episode in May 2002, at which time the show's Million Dollar Masters invitational tournament also occurred.[182] The Music Hall was used again in November 2006 for a 2-week Celebrity Jeopardy! event.[183]

In 1988, David Letterman hosted Late Night With David Letterman's Sixth Anniversary Special at Radio City Music Hall, and did so again for the Tenth Anniversary Special in 1992.[184][185] The next year, Lyons Group (parent company of Barney & Friends at the time), taped a live stage show called Barney Live in New York City at the theater.[186] In February 1998, Radio City Music Hall was a setting for the Sesame Street music special Elmopalooza, with Jon Stewart, David Alan Grier and others with the cast of Sesame Street and the Muppets.[187][188][189]

In October 2001, the concert Come Together: A Night for John Lennon's Words and Music was simulcast live from the theater on The WB and TNT. The concert had been delayed following the September 11 attacks the month before.[190][191]

In 2013, it was announced that America's Got Talent would hold its live shows from the stage at Radio City Music Hall starting with the eighth season; it had previously held the live shows at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. The move to have the live shows at Radio City Music Hall was because of the New York state tax credit, and the proximity of The Today Show and Late Night with Jimmy Fallon.[192] They also hosted their live shows from the Music Hall in 2014, during their ninth season.[193] The last live show performances at the Music Hall occurred in 2015, during the 10th season.[194]

Sports

The first sports event at Radio City Music Hall was a boxing card headlined by Roy Jones Jr. and David Telesco that took place on January 15, 2000.[195][65] On April 13, 2013, Nonito Donaire faced Guillermo Rigondeaux in a boxing card held at Radio City Music Hall.[196]

In 2004, the WNBA's New York Liberty played six home games at the Music Hall while their then-regular home, Madison Square Garden, prepared to host the 2004 Republican National Convention.[65] The Liberty played their first game in front of 5,945 fans against the Detroit Shock in July 2004. Courtside seats were stage left and stage right along the baseline and the Rockettes performed at halftime.[197] The court from Madison Square Garden was moved to Radio City Music Hall during this time.[198]

Radio City Music Hall was the site of the NFL Draft between 2006 and 2014.[199][200] Prior to being held in the Music Hall, the NFL Draft had been hosted at other locations in New York City since 1965, but after the 2014 draft, the National Football League hosted the draft in a series of other cities nationwide.[200][201]

Gallery

Statue Eve by Gwen Lux in the lobby

Statue Eve by Gwen Lux in the lobby- Hydraulics pit beneath the Great Stage

Underside of the Great Stage

Underside of the Great Stage The backstage control room

The backstage control room The elevator hydraulics controls

The elevator hydraulics controls The Grand Foyer with Christmas decorations for the Christmas Spectacular

The Grand Foyer with Christmas decorations for the Christmas Spectacular

References

Notes

- The Grammys, which alternated between New York City and Hollywood, were moved to Hollywood in 2004, as have the Daytime Emmys, off and on, since 2006.

- The mural was originally unnamed, but the Rockefeller Center Art Committee named it Men Without Women, after the Ernest Hemingway short-story collection that had been published the same year of the mural's commission.[161]

Citations

- "Rockefeller Center". Tishman Speyer Properties. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978

- "First Steel Column Erected in 70-Story Rockefeller Unit". The New York Times. March 8, 1932. p. 43. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- "Airline Building is Dedicated Here; Governors of 17 States Take Part by Pressing Keys" (PDF). The New York Times. October 16, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- 30 Rockefeller Plaza was the first building to start construction, in March 1932.[4] The last building was completed in 1940.[5]

- Glancy, Dorothy J. (January 1, 1992). "Preserving Rockefeller Center". 24 Urb. Law. 423. Santa Clara University School of Law: 431. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 3.

- Okrent 2003, p. 21.

- Adams 1985, p. 13.

- Krinsky 1978, pp. 31–32.

- "Rockefeller Site For Opera Dropped" (PDF). The New York Times. December 6, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Balfour 1978, p. 11.

- Krinsky 1978, pp. 16, 48–50.

- Okrent 2003, pp. 137–138.

- "Rockefeller Plans Huge Culture Centre" (PDF). The New York Times. June 14, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Adams 1985, p. 45.

- Okrent 2003, p. 177.

- Okrent 2003, p. 203.

- Balfour 1978, p. 91.

- Okrent 2003, p. 213.

- Krinsky 1978, p. 64.

- Krinsky 1978, p. 65.

- Adams 1985, p. 46.

- Balfour 1978, p. 92.

- Gilligan, Edmund (November 29, 1932). "Roxy Presents New Mood" (PDF). The New York Sun. p. 20. Retrieved November 11, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- Brock, H.I. (April 5, 1931). "Problems Confronting the Designers of Radio City" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- "Radio City Leaders Plan Foreign Tour" (PDF). The New York Times. September 11, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- Balfour 1978, p. 93; Krinsky 1978, p. 65;Okrent 2003, p. 214; Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 5.

- Krinsky 1978, p. 66.

- Okrent 2003, p. 215.

- Balfour 1978, p. 94.

- Okrent 2003, pp. 217–218.

- Okrent 2003, p. 217.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 5.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 9.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 7.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 10.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 1.

- Okrent 2003, p. 218.

- Okrent 2003, p. 220.

- Okrent 2003, pp. 220–221.

- "World's Largest Theater in Rockefeller Center Will Seat Six Thousand". Popular Mechanics: 252. August 1932. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- "Rockefeller Plans Huge Culture Centre; 4 Theatres in $350,000,000 5th Av. Project; A huge theatrical venture which will exploit television, music radio, talking pictures and plays will be erected, it was disclosed last night, on the site assembled by John D. Rockefeller Jr. between Fifth and" (PDF). The New York Times. June 14, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Adams 1985, p. 40.

- "Facade 'Topped Out' In Rockefeller Unit; Last Stone Laid on Exterior of Music Hall – Work on Other Buildings Speeded" (PDF). The New York Times. August 11, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- "Radio City buys 15,000 Miles of Copper Wire; Early Start Looms in Construction Work". The New York Times. August 18, 1931. p. 23. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- Balfour 1978, p. 96.

- Okrent 2003, pp. 235–236.

- Okrent 2003, pp. 239–243.

- "Mount Vernon Shares Glory at Opening of Radio City Music Hall in New York" (PDF). Daily Argus. Mount Vernon, New York. December 28, 1932. p. 16. Retrieved November 10, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Music Hall Marks New Era In Design; Many Traditions in Building of Theatres Cast Aside for Modern Devices" (PDF). The New York Times. December 28, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- Okrent 2003, pp. 241–242.

- Okrent 2003, p. 242.

- Okrent 2003, p. 244.

- Ramsaye, Terry (January 14, 1933). "Static in Radio City". Motion Picture Herald. p. 11. Retrieved November 28, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 18.

- "World's Biggest Playhouse Opens". Literary Digest. 115: 16. January 14, 1933.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 19.

- Balfour 1978, p. 95.

- Hall, Mordaunt (January 12, 1933). "Radio City Music Hall Shows a Melodrama of China as Its First Pictorial Attraction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- "More than 8,000,000 Attended Radio City Houses in First Year". Motion Picture Herald. January 20, 1934. p. 27. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- "This Day in History: Radio City Music Hall opens". History.com. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Radio City Music Hall in New York, NY". Cinema Treasures. September 23, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Wang, Vivian (January 5, 2018). "New York Today: The Many Lives of Radio City Music Hall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- O'Haire, Patricia (March 26, 1982). "Radio City hits half-century". New York Daily News. pp. 104, 106, 112 – via newspapers.com

- "Thousands Attend Services At Dawn; Largest of City's Crowds Is Gathering of 8,000 in Radio City Music Hall". The New York Times. April 10, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Movie Show Dec. 17 For Big Brothers; Women Active in Organization Take Over Block of Seats at Music Hall for Benefit". The New York Times. November 19, 1953. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Big Brothers, Inc., Plans a Benefit At Music Hall; Proceeds of Film Dec. 10 and 11 Will Assist Work for Needy Boys". The New York Times. November 1, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Okrent 2003, p. 429.

- "Theater Still Finds Key to Success in Its Program Formula". The New York Times. December 10, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Radio City Music Hall will close". Press and Sun-Bulletin. Binghamton, NY. January 5, 1978. p. 17. Retrieved December 15, 2018 – via newspapers.com

- "Music Hall Plans A 5-Day Shutdown; Ceiling Paint Job and Change of Curtain Set March 1–5". The New York Times. February 5, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Radio City Organ Gets Repairs in Off Hours". The New York Times. December 16, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Gelmis, Joseph (August 31, 1970). "Exhibitionists and the Games They Play". New York Magazine. p. 56. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- Okrent 2003, pp. 429–430.

- Okrent 2003, p. 430.

- Shepard, Richard F. (April 19, 1979). "Music Hall to Be Restored". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Threatens Demolition of the Music Hall; Rockettes Kick Up a Storm in City Hall Routine". New York Daily News. March 15, 1978. pp. 5, 26 – via newspapers.com

- Oelsner, Lesley (January 7, 1978). "Efforts to Save‐Music Hall Started". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Ferretti, Fred (April 7, 1978). "Agreement Reached On Radio City Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

-

- M. A Farber (January 5, 1978). "Radio City Music Hall to Close After. Easter Show, Koch Is Told". The New York Times. p. A1. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Clines, Francis X. (March 1, 1978). "About New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Schumach, Murry (January 8, 1978). "Nostalgia Draws Music Hall Crowds Despite Cold". The New York Times. p. 29. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Grantz, Roberta B. Grantz & Cook, Joy (March 14, 1978). "Music Hall: Krupsak blames regime for woes". New York Post. p. 8.

Lt. Gov. Mary Ann Krupsak, leading the fight to save Radio City Music Hall, said today she was "convinced there has been a policy by Rockefeller Center to let Radio City Music Hall go downhill." She said a study showed that the management over the past 10 years had stacked the deck against the theater, placing a "disproportionate tax burden, management costs and other expenses" on the 6500-seat theater to show it no longer was economically viable as a movie house.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Oelsner, Leslie (January 7, 1978). "Public and Private Efforts to Save Radio City Music Hall Are Started". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- McDowell, Edwin (March 29, 1978). "Interior of Music Hall Designated As Landmark Despite Objections". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "It's a Landmark Decision for Radio City Music Hall". New York Daily News. March 29, 1978. p. 668. Retrieved December 15, 2018 – via newspapers.com

- Huxtable, Ada Louise (April 22, 1979). "Architecture View". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Times, Special to the New York (April 13, 1978). "Agreement With U.D.C. Keeps Music Hall Open Indefinitely". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Radio City in National Register". New York Times. May 13, 1978. p. 26.

- Fried, Joseph P. (December 26, 1978). "3 Plans Weighed By State to Keep Music Hall Open". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Radio City Tower Urged". The New York Times. February 11, 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Radio City Chandeliers Become Party Lights". The New York Times. April 27, 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Morgan, Thomas (March 27, 1986). "'Snow White' To Rock, Radio City Diversifies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- Leogrande, Ernest (January 15, 1980). "Music Hall gets a lift". New York Daily News. p. 198. Retrieved December 28, 2018 – via newspapers.com

- Holden, Stephen (September 10, 1983). "Radio City Shifts Focus To Pop Music Concerts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- Freudenheim, Betty (March 19, 1987). "Quest for a Curtain for a Historic Hall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- Lueck, Thomas J. (December 4, 1997). "Lease of Radio City Music Hall Keeps Rockettes Kicking". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- Collins, Glenn (February 21, 1999). "Bringing Up the Basement; Rockefeller Center Is Turning Its Underground Concourse Into a Shiny New Shopping Zone. Lost in the Bargain, Preservationists Say, Is an Art Deco Treasure". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Iovine, Julie V. (September 6, 1999). "Piece by Piece, a Faded Icon Regains Its Art Deco Glow". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Collins, Glenn (October 10, 1999). "Travel Advisory; Live From Radio City!". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Pristin, Terry (January 30, 1999). "For Radio City Restoration, a $2.5 Million Sales Tax Break". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Look Divine! Radio City restored, reopened & radiant". New York Daily News. October 5, 1999. p. 7. Retrieved December 15, 2018 – via newspapers.com

- Kennedy, Mark (December 23, 2016). "Backlash kicked up as the Rockettes picked for inauguration". FOX 28 News. Associated Press. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- "Audio reveals Radio City Rockettes' tension over Trump inauguration: Some members of the dance group differ from their employer over performing for the president-elect". Portland Press Herald. Associated Press. January 3, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- Teodorczuk, Tom (December 2016). "Rockettes Facing 'Furious' Liberal Boycott For Performing at Trump Inauguration". Heat Street. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- Slattery, Denis; Shahrigian, Shant; Greene, Leonard. "Gov. Cuomo bans public events with more than 500 people to fight coronavirus; Mayor de Blasio declares state of emergency in NYC". nydailynews.com. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- Marsh, Julia; O'Neill, Natalie (March 12, 2020). "Here's what is closed in NYC over coronavirus pandemic". New York Post. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- Durkin, Erin; Eisenberg, Amanda (March 12, 2020). "City in state of emergency as coronavirus outlook becomes more dire". Politico PRO. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "The 74th Annual Tony Awards to Be Postponed". Tony Awards. March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- McPhee, Ryan (March 25, 2020). "2020 Tony Awards Put on Hold as Coronavirus Pandemic Causes Broadway Shutdown". Playbill. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 325, 326. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- Adams 1985, pp. 53–54.

- Storey, Walter Rendell (December 25, 1932). "Modern Decorations on a Grand Scale" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Adams 1985, pp. 47–49.

- Roussel 2006, p. 13.

- Miller, Moscrip (1937). "Mystery on Sixth Ave" (PDF). Screen & Radio Weekly. Retrieved November 10, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- Balfour 1978, p. 97.

- Federal Writers' Project 1939, p. 338.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, pp. 12–13.

- "The art of Rockefeller Center / Christine Roussel. – Version details". Trove. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 11.

- Roussel 2006, p. 17.

- Roussel 2006, p. 51.

- Roussel 2006, p. 24.

- Roussel 2006, p. 14.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 14.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 12.

- Roussel 2006, p. 16.

- Roussel 2006, p. 18.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, pp. 11, 15.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 13.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 15.

- Roussel 2006, p. 23.

- Roussel 2006, p. 48.

- Roussel 2006, p. 25.

- "Secrets of the Magic Theater". Popular Mechanics: 27. January 1941. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- Balfour 1978, p. 93.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 4.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, pp. 13–14.

- Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, pp. 14–15.

- "Radio City Music Hall To Be Opened Dec. 27; Brilliant Program Is Planned for Premiere – Theatre to Have Dormitory for the Chorus" (PDF). The New York Times. November 18, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Boland Jr., Ed (August 18, 2002). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- "Native Art to Lead in New Music Hall; Rockefeller Centre Unit Will Offer Striking Display of Modern Decorations" (PDF). The New York Times. October 3, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- Balfour 1978, p. 141; Okrent 2003, p. 218; Radio City Music Hall Landmark Designation 1978, p. 9; Roussel 2006, p. 20

- Poulin, Richard (November 1, 2012). Graphic Design And Architecture, A 20th Century History. Rockport. p. 97. ISBN 978-1592537792.

- Roussel 2006, p. 44.

- Dunphy, Mike (November 17, 2014). "The Art of Rockefeller Center: Top 10 Things Not to Miss". Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- Roussel 2006, p. 26.

- Roussel 2006, p. 30.

- Roussel 2006, p. 40.

- Leonard, Gayle (June 13, 2009). "Go in Style: 2009 Finalists for Best Public Restroom". Thirsty in Suburbia. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- Roussel 2006, pp. 28–29.

- Roussel 2006, p. 33.

- Marshall, Colin (September 23, 2013). "Frida Kahlo Writes a Personal Letter to Georgia O'Keeffe After O'Keeffe's Nervous Breakdown". Open Culture. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- Roussel 2006, p. 34.

- Roussel 2006, p. 35.

- Roussel 2006, p. 36.

- Roussel 2006, p. 43.

- Roussel 2006, p. 47.

- "Stuart Davis at the Whitney – The painter behind a prized Radio City mural". Rockefeller Center. August 30, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2020.

- Kramer, Hilton (April 3, 1975). "Music Hall Mural Going to Museum". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Roussel 2006, p. 39.

- Rockwell, John (March 19, 1973). "Pink Floyd Offers Rock In Music Hall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- Palmer, Robert (October 24, 1980). "Rock: The Grateful Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- "DEVO Setlist at Radio City Music Hall, New York". setlist.fm. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- DEVO [@DEVO] (October 31, 2016). "Happy Halloween! On this day, October 31st in 1981, DEVO performed at Radio City Music Hall in NYC" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Flashy Piano Virtuoso Liberace Is Dead At 67". Washington Post. February 5, 1987. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- Lawrence, Jesse (June 19, 2015). "Tony Bennett And Lady Gaga's Radio City Music Hall Residency Averaging $380 Ticket On Resale Market". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Gamboa, Glenn (January 23, 2018). "Britney Spears' Vegas show set for Radio City". Newsday. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- "What You Need To Know About Tickets To The Christina Aguilera Tour". Forbes. June 3, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- "Mariah Carey, Slick Rick & Blood Orange Perform 'Giving Me Life' In NYC: Watch". Billboard. March 26, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- "Mariah Carey energized by new music at Radio City". Newsday. March 25, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- "Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers and Others in a Musical Film -- Walt Disney's New 'Silly Symphony.'". The New York Times. December 22, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Radio City Entertainment (2007). Radio City Spectacular: A Photographic History of the Rockettes and Christmas Spectacular. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-156538-0. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Dietz, D. (2016). The Complete Book of 1990s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-4422-7214-9. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. February 22, 1997. p. 10. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- "A Marvelous Exploration of the Truly Bizarre at Radio City Music Hall written and directed by François Girard". Cirque du Soleil (Press Release). November 9, 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- "Acrobatic Spectable Zarkana by Cirque du Soleil to Establish Residency at Aria Resort & Casino Following Successful Worldwide Run. Show to Find Permanent Home in Las Vegas Starting October 2012". March 7, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- McCarthy, Sean L. (November 5, 2007). "'Wheel of Fortune' takes 3-week spin in Radio City - NY Daily News". New York Daily News. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Starr, Michael (May 20, 2003). "Starr Report". New York Post. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "'Jeopardy' buzzes in at Radio City". Variety. April 2, 2002. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- "Celebrity Circuit". CBS News. October 11, 2006. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Kogan, Rick (February 5, 1992). "David Letterman Looks Back on a Decade of Success and Forward". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Carter, Bill (January 29, 1992). "Is Letterman Mad At NBC? He Says No And He Says Yes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Jarvik, Laurence (February 1, 1998). PBS: Behind the Screen. Crown Publishing Group. p. 50. ISBN 9780761512912.

- Dunne, Susan (April 16, 1998). "Elmopalooza!". courant.com. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- Scott, Tony (February 19, 1998). "Elmopalooza!". Variety. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- "'Elmopalooza!' Musical Tries a Little Too Hard". Los Angeles Times. February 20, 1998. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- "Spacey plays 'Mind Games' at Lennon tribute". Variety. October 4, 2001. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- "A Lennon Tribute Revived". The New York Times. September 29, 2001. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- "'America's Got Talent' Moves to New York for Season 8". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- "'America's Got Talent' live at Radio City this summer". New York Post. April 8, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- "NBC's Top-rated Summer Series "America's Got Talent" Returns with Simon Cowell Joining the Judges". TV Weekly Now. May 25, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Lena Williams (May 18, 2004). "Pro Basketball; Coming Soon: The W.N.B.A. At Radio City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- Dan Rafael (April 14, 2014). "Rigondeaux bores, but bests Donaire". ESPN. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- Lena Williams (July 25, 2004). "Pro Basketball; Liberty Opens Big on Its Home, Er, Stage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- Williams, Lena (May 18, 2004). "Pro Basketball; Coming Soon: The W.N.B.A. At Radio City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Salomone, Dan (October 2, 2014). "NFL Draft headed to Chicago in 2015". Giants.com. New York Giants. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- Lauterbach, David (April 14, 2017). "New York wants to host the NFL Draft again, but other cities want to get involved". The Comeback. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- Myers, Gary (April 12, 2017). "New York now looking to bring back NFL Draft, but Big Apple has plenty of competition". New York Daily News. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

Sources

- Adams, Janet (1985). "Rockefeller Center Designation Report" (PDF). City of New York; New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Balfour, Alan (1978). Rockefeller Center: Architecture as Theater. McGraw-Hill, Inc. ISBN 978-0070034808.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). "New York City Guide". New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- Krinsky, Carol H. (1978). Rockefeller Center. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-502404-3.

- Okrent, Daniel (2003). Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0142001776.

- "Radio City Music Hall" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 28, 1978. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Roussel, Christine (May 17, 2006). The Art of Rockefeller Center. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-3930-6082-9.

Further reading

- Francisco, Charles. An Affectionate History of the World's Greatest Theatre, with special color photography by James Stewart Morcom and Vito Torelli, New York: Dutton, 1979. ISBN 0-525-18792-8.

- Novellino-Mearns, Rosemary. Saving Radio City Music Hall – A Dancer's True Story, TurningPointPress LLC, 2015. ISBN 978-0-9908556-1-3.

- "World's Biggest Stage Is a Marvel Of Mechanics", February 1933, Popular Science article on major work on Radio City Hall in the early 1930s

- "World's Largest Theater in Rockefeller Center Will Seat Six Thousand Persons" Popular Mechanics, August 1932

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radio City Music Hall. |

- Official website

- Radio City Music Hall at Cinema Treasures

- Radio City Music Hall collection of the papers of James Stewart Morcom and John William Keck, 1926–1994, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Radio City Music Hall collection of the designs of James Stewart Morcom and John William Keck, 1933–1979, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

| Preceded by Jacob K. Javits Convention Center |

Venues of the NFL Draft 2006–2014 |

Succeeded by Auditorium Theatre |