USS Missouri (BB-63)

USS Missouri (BB-63) ("Mighty Mo" or "Big Mo") is an Iowa-class battleship and was the third ship of the United States Navy to be named after the U.S. state of Missouri. Missouri was the last battleship commissioned by the United States and is best remembered as the site of the surrender of the Empire of Japan, which ended World War II.

USS Missouri at sea in her 1980s configuration | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Namesake: | State of Missouri |

| Ordered: | 12 June 1940 |

| Builder: | Brooklyn Navy Yard |

| Laid down: | 6 January 1941 |

| Launched: | 29 January 1944 |

| Sponsored by: | Mary Margaret Truman |

| Commissioned: | 11 June 1944 |

| Decommissioned: | 26 February 1955 |

| Recommissioned: | 10 May 1986 |

| Decommissioned: | 31 March 1992 |

| Stricken: | 12 January 1995 |

| Identification: | Hull symbol: BB-63 |

| Motto: | "Strength for Freedom" |

| Nickname(s): | "Mighty Mo" or "Big Mo" |

| Honors and awards: | 11 battle stars |

| Status: | Museum ship in Pearl Harbor |

| Notes: | Final battleship to be completed by the United States |

| Badge: |

|

| General characteristics (1943) | |

| Class and type: | Iowa-class battleship |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 887 ft 3 in (270.43 m) |

| Beam: | 108 ft 2 in (32.97 m) |

| Draft: | 37 ft 9 in (11.51 m) (full load) |

| Speed: | 32.7 kn (37.6 mph; 60.6 km/h) |

| Range: | 14,890 mi (23,960 km) |

| Complement: | 2,700 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

| General characteristics (1984) | |

| Class and type: | Iowa-class battleship |

| Complement: | 1,851 officers and enlisted |

| Sensors and processing systems: | |

| Electronic warfare & decoys: |

|

| Armament: |

|

USS Missouri (BB-63) | |

| |

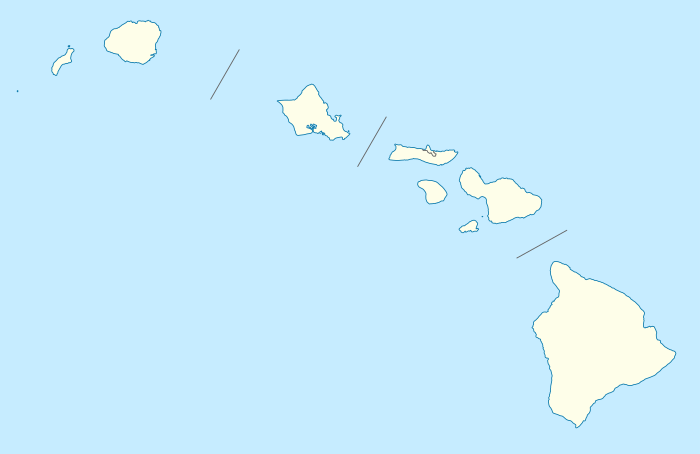

| Location | Pearl Harbor, Hawaii |

| Coordinates | 21°21′44″N 157°57′12″W |

| Built | 1944 |

| Architect | New York Naval Shipyard |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000877 |

| Added to NRHP | 14 May 1971 |

Missouri was ordered in 1940 and commissioned in June 1944. In the Pacific Theater of World War II she fought in the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa and shelled the Japanese home islands, and she fought in the Korean War from 1950 to 1953. She was decommissioned in 1955 into the United States Navy reserve fleets (the "Mothball Fleet"), but reactivated and modernized in 1984 as part of the 600-ship Navy plan, and provided fire support during Operation Desert Storm in January/February 1991.

Missouri received a total of 11 battle stars for service in World War II, Korea, and the Persian Gulf, and was finally decommissioned on 31 March 1992 after serving a total of 17 years of active service, but remained on the Naval Vessel Register until her name was struck in January 1995. In 1998, she was donated to the USS Missouri Memorial Association and became a museum ship at Pearl Harbor.

Construction

Missouri was one of the Iowa-class "fast battleship" designs planned in 1938 by the Preliminary Design Branch at the Bureau of Construction and Repair. She was laid down at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on 6 January 1941, launched on 29 January 1944 and commissioned on 11 June with Captain William Callaghan in command. The ship was the third of the Iowa class, but the fourth and final Iowa-class ship commissioned by the U.S. Navy.[1][2][note 1][note 2] The ship was christened at her launching by Mary Margaret Truman, daughter of Harry S. Truman, then a United States Senator from Missouri.[3]

Missouri's main battery consisted of nine 16 in (406 mm)/50 cal Mark 7 guns, which could fire 2,700 lb (1,200 kg) armor-piercing shells some 20 mi (32.2 km). Her secondary battery consisted of twenty 5 in (127 mm)/38 cal guns in twin turrets, with a range of about 10 mi (16 km). With the advent of air power and the need to gain and maintain air superiority came a need to protect the growing fleet of allied aircraft carriers; to this end, Missouri was fitted with an array of Oerlikon 20 mm and Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft guns to defend allied carriers from enemy airstrikes. When reactivated in 1984 Missouri had her 20 mm and 40 mm AA guns removed, and was outfitted with Phalanx CIWS mounts for protection against enemy missiles and aircraft, and Armored Box Launchers and Quad Cell Launchers designed to fire Tomahawk missiles and Harpoon missiles, respectively.[4] Missouri and her sister ship Wisconsin were fitted with thicker transverse bulkhead armor, 14.5 inches (368 mm), compared to 11.3 inches (287 mm) in the first two ships of her class, the Iowa and New Jersey.[5]

Missouri was the last U.S. battleship to be completed.[2][note 3] Wisconsin, the highest-numbered U.S. battleship built, was completed before Missouri. The last-two Iowa-class battleships, Illinois and Kentucky, were ordered but cancelled, and all five of the twelve-gun Montana-class battleship, BB-67 to BB-71, that were ordered in May 1942, were also cancelled by late July 1943.

World War II (1944–1945)

Shakedown and service with Task Force 58, Admiral Mitscher

After trials off New York and shakedown and battle practice in the Chesapeake Bay, Missouri departed Norfolk, Virginia on 11 November 1944, transited the Panama Canal on 18 November and steamed to San Francisco for final fitting out as fleet flagship. She stood out of San Francisco Bay on 14 December and arrived at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on 24 December 1944. She departed Hawaii on 2 January 1945 and arrived in Ulithi, West Caroline Islands on 13 January. There she was temporary headquarters ship for Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher. The battleship put to sea on 27 January to serve in the screen of the Lexington carrier task group of Mitscher's TF 58, and on 16 February the task force's aircraft carriers launched the first naval air strikes against Japan since the famed Doolittle raid, which had been launched from the carrier Hornet in April 1942.[3]

Missouri then steamed with the carriers to Iwo Jima where her main guns provided direct and continuous support to the invasion landings begun on 19 February. After TF 58 returned to Ulithi on 5 March, Missouri was assigned to the Yorktown carrier task group. On 14 March, Missouri departed Ulithi in the screen of the fast carriers and steamed to the Japanese mainland. During strikes against targets along the coast of the Inland Sea of Japan beginning on 18 March, Missouri shot down four Japanese aircraft.[3]

Raids against airfields and naval bases near the Inland Sea and southwestern Honshū continued. When the carrier Franklin incurred battle damage, the Missouri's carrier task group provided cover for the Franklin's retirement toward Ulithi until 22 March, then set course for pre-invasion strikes and bombardment of Okinawa.[3]

Missouri joined the fast battleships of TF 58 in bombarding the southeast coast of Okinawa on 24 March, an action intended to draw enemy strength from the west coast beaches that would be the actual site of invasion landings. Missouri rejoined the screen of the carriers as Marine and Army units stormed the shores of Okinawa on the morning of 1 April. An attack by Japanese forces was repulsed successfully.[3]

On 11 April, a low-flying kamikaze Zero, although fired upon, crashed on Missouri's starboard side, just below her main deck level. The starboard wing of the plane was thrown far forward, starting a gasoline fire at 5 in (127 mm) Gun Mount No. 3. The battleship suffered only superficial damage, and the fire was brought quickly under control.[3] The remains of the pilot were recovered on board the ship just aft of one of the 40 mm gun tubs. Although crewmen wanted to hose the remains over the side, Captain Callaghan decided that the young Japanese pilot had done his job to the best of his ability, and with honor, so he should be given a military funeral. The following day he was buried at sea with military honors.[6] The dent made by the Zero in the Missouri's side remains to this day.[7]

About 23:05 on 17 April, Missouri detected an enemy submarine 12 mi (19 km) from her formation. Her report set off a hunter-killer operation by the light carrier Bataan and four destroyers, which sank the Japanese submarine I-56.[3]

Missouri was detached from the carrier task force off Okinawa on 5 May and sailed for Ulithi. During the Okinawa campaign she had shot down five enemy planes, assisted in the destruction of six others, and scored one probable kill. She helped repel 12 daylight attacks of enemy raiders and fought off four night attacks on her carrier task group. Her shore bombardment destroyed several gun emplacements and many other military, governmental, and industrial structures.[3]

Service with the Third Fleet, Admiral Halsey

Missouri arrived at Ulithi on 9 May 1945, and then proceeded to Apra Harbor, Guam, arriving on 18 May.[3] That afternoon Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., Commander Third Fleet, brought his staff from cruiser Louisville onto the Missouri.[note 4] She passed out of the harbor on 21 May, and by 27 May was again conducting shore bombardment against Japanese positions on Okinawa. Missouri led the 3rd Fleet in strikes on airfields and installations on Kyūshū on 2–3 June. She rode out a fierce storm on 5 and 6 June. Some topside fittings were smashed, but Missouri suffered no major damage. Her fleet again struck Kyūshū on 8 June, then hit hard in a coordinated air-surface bombardment before retiring towards Leyte. She arrived at San Pedro Bay, Leyte on 13 June, after almost three months of continuous operations in support of the Okinawa campaign.[3]

Here she rejoined the powerful 3rd Fleet in strikes at the heart of Japan from within its home waters. The fleet set a northerly course on 8 July to approach the Japanese main island, Honshū. Raids took Tokyo by surprise on 10 July, followed by more devastation at the juncture of Honshū and Hokkaidō, the second-largest Japanese island, on 13–14 July. For the first time, naval gunfire destroyed a major installation within the home islands when Missouri joined in a shore bombardment on 15 July that severely damaged the Nihon Steel Co. and the Wanishi Ironworks at Muroran, Hokkaido.[3]

During the nights of 17 and 18 July, Missouri bombarded industrial targets in Honshū. Inland Sea aerial strikes continued through 25 July, and Missouri guarded the carriers as they attacked the Japanese home islands.[3]

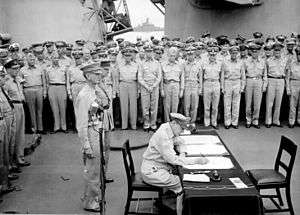

Signing of the Japanese Instrument of Surrender

Strikes on Hokkaidō and northern Honshū resumed on 9 August, the day the second atomic bomb was dropped.[3]

After the Japanese agreed to surrender, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser of the Royal Navy, the Commander of the British Pacific Fleet, boarded Missouri on 16 August and conferred the honour of Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire upon Admiral Halsey. Missouri transferred a landing party of 200 officers and men to the battleship Iowa for temporary duty with the initial occupation force for Tokyo on 21 August. Missouri herself entered Tokyo Bay early on 29 August to prepare for the signing by Japan of the official instrument of surrender.[3] High-ranking military officials of all the Allied Powers were received on board on 2 September, including Chinese general Hsu Yung-Ch'ang, British admiral of the Fleet Sir Bruce Fraser, Soviet lieutenant-general Kuzma Nikolaevich Derevyanko, Australian general Sir Thomas Blamey, Canadian colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave, French général d'armée Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, Dutch vice admiral Conrad Emil Lambert Helfrich, and New Zealand air vice marshal Leonard Isitt.

Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz boarded shortly after 0800, and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allies, came on board at 0843. The Japanese representatives, headed by Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, arrived at 0856. At 0902, General MacArthur stepped before a battery of microphones and opened the 23-minute surrender ceremony to the waiting world by stating,[3] "It is my earnest hope—indeed the hope of all mankind—that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past, a world founded upon faith and understanding, a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance, and justice."[9]

During the surrender ceremony, the deck of Missouri was decorated with a 31-star American flag that had been taken ashore by Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853 after his squadron of "Black Ships" sailed into Tokyo Bay to force the opening of Japan's ports to foreign trade. This flag was actually displayed with the reverse side showing, i.e., stars in the upper right corner: the historic flag was so fragile that the conservator at the Naval Academy Museum had sewn a protective linen backing to one side to help secure the fabric from deteriorating, leaving its "wrong side" visible. The flag was displayed in a wood-framed case secured to the bulkhead overlooking the surrender ceremony.[10] Another U.S. flag was raised and flown during the occasion, a flag that some sources have indicated was in fact that flag which had flown over the U.S. Capitol on 7 December 1941. This is not true; it was a flag taken from the ship's stock, according to Missouri's commanding officer, Captain Stuart "Sunshine" Murray, and it was "...just a plain ordinary GI-issue flag".[11]

By 09:30 the Japanese emissaries had departed. In the afternoon of 5 September, Admiral Halsey transferred his flag to the battleship South Dakota, and early the next day Missouri departed Tokyo Bay. As part of the ongoing Operation Magic Carpet she received homeward bound passengers at Guam, then sailed unescorted for Hawaii. She arrived at Pearl Harbor on 20 September and flew Admiral Nimitz's flag on the afternoon of 28 September for a reception.[3]

Post-war (1946–1950)

The next day, Missouri departed Pearl Harbor bound for the eastern seaboard of the United States. She reached New York City on 23 October and hoisted the flag of Atlantic Fleet commander Admiral Jonas Ingram. Four days later, Missouri boomed out a 21-gun salute as President Truman boarded for Navy Day ceremonies.[3]

After an overhaul in the New York Naval Shipyard and a training cruise to Cuba, Missouri returned to New York. During the afternoon of 21 March 1946, she received the remains of the Turkish Ambassador to the United States, Münir Ertegun. She departed on 22 March for Gibraltar, and on 5 April anchored in the Bosphorus off Istanbul. She rendered full honors, including the firing of 19-gun salutes during the transfer of the remains of the late ambassador and again during the funeral ashore.[3]

Missouri departed Istanbul on 9 April and entered Phaleron Bay, Piraeus, Greece, the following day for an overwhelming welcome by Greek government officials and anti-communist citizens. Greece had become the scene of a civil war between the communist World War II resistance movement and the returning Greek government-in-exile. The United States saw this as an important test case for its new doctrine of containment of the Soviet Union. The Soviets were also pushing for concessions in the Dodecanese to be included in the peace treaty with Italy and for access through the Dardanelles strait between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. The voyage of Missouri to the eastern Mediterranean symbolized America's strategic commitment to the region. News media proclaimed her a symbol of U.S. interest in preserving both nations' independence.[3]

Missouri departed Piraeus on 26 April, touching at Algiers and Tangiers before arriving at Norfolk on 9 May. She departed for Culebra Island on 12 May to join Admiral Mitscher's 8th Fleet in the Navy's first large-scale postwar Atlantic training maneuvers. The battleship returned to New York City on 27 May, and spent the next year steaming Atlantic coastal waters north to the Davis Strait and south to the Caribbean on various Atlantic command training exercises.[3] On 13 December, during a target practice exercise in the North Atlantic, a star shell accidentally struck the battleship, but without causing injuries.[12]

_gun_turret%2C_1948_Midshipmen%E2%80%99s_Practice_Cruise_(37781879662).jpg)

Missouri arrived at Rio de Janeiro on 30 August 1947 for the Inter-American Conference for the Maintenance of Hemisphere Peace and Security. President Truman boarded on 2 September to celebrate the signing of the Rio Treaty, which broadened the Monroe Doctrine by stipulating that an attack on any one of the signatory American countries would be considered an attack on all.[3]

The Truman family boarded Missouri on 7 September 1947 to return to the United States and disembarked at Norfolk on 19 September. Her overhaul in New York—which lasted from 23 September to 10 March 1948—was followed by refresher training at Guantanamo Bay. The summer of 1948 was devoted to midshipman and reserve training cruises. Also in 1948, Missouri became the first battleship to host a helicopter detachment, operating two Sikorsky HO3S-1 machines for utility and rescue work.[13] The battleship departed Norfolk on 1 November 1948 for a second three-week Arctic cold-weather training cruise to the Davis Strait. During the next two years, Missouri participated in Atlantic command exercises from the New England coast to the Caribbean, alternated with two midshipman summer training cruises. She was overhauled at Norfolk Naval Shipyard from 23 September 1949 to 17 January 1950.[3]

Throughout the latter half of the 1940s, the various service branches of the United States had been reducing their inventories from their World War II levels. For the Navy, this resulted in several vessels of various types being decommissioned and either sold for scrap or placed in one of the various United States Navy reserve fleets scattered along the East and West Coast of the United States. As part of this contraction, three of the Iowa-class battleships had been de-activated and decommissioned; however, President Truman refused to allow Missouri to be decommissioned. Against the advice of Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson, Secretary of the Navy John L. Sullivan, and Chief of Naval Operations Louis E. Denfeld, Truman ordered Missouri to be maintained with the active fleet partly because of his fondness for the battleship and partly because the battleship had been christened by his daughter Margaret Truman.[14][15]

Then the only U.S. battleship in commission, Missouri was proceeding seaward on a training mission from Hampton Roads early on 17 January 1950 when she ran aground 1.6 mi (2.6 km) from Thimble Shoal Light, near Old Point Comfort. She hit shoal water a distance of three ship-lengths from the main channel. Lifted some 7 feet (2.1 m) above waterline, she stuck hard and fast.[3] With the aid of tugboats, pontoons, and a rising tide, she was refloated on 1 February 1950 and repaired.[3]

The Korean War (1950–1953)

In 1950, the Korean War broke out, prompting the United States to intervene in the name of the United Nations. President Truman was caught off guard when the invasion struck,[note 5] but quickly ordered U.S. forces stationed in Japan into South Korea. Truman also sent U.S.-based troops, tanks, fighter and bomber aircraft, and a strong naval force to Korea to support the Republic of Korea. As part of the naval mobilization Missouri was called up from the Atlantic Fleet and dispatched from Norfolk on 19 August to support UN forces on the Korean peninsula.[3]

Missouri arrived just west of Kyūshū on 14 September, where she became the flagship of Rear Admiral Allan Edward Smith. The first American battleship to reach Korean waters, she bombarded Samchok on 15 September 1950 in an attempt to divert troops and attention from the Incheon landings. This was the first time since World War II that Missouri had fired her guns in anger, and in company with the cruiser Helena and two destroyers, she helped prepare the way for the U.S. Eighth Army offensive.[3]

Missouri arrived at Incheon on 19 September, and on 10 October became flagship of Rear Admiral J. M. Higgins, commander, Cruiser Division 5 (CruDiv 5). She arrived at Sasebo on 14 October, where she became flagship of Vice Admiral A. D. Struble, Commander, 7th Fleet. After screening the aircraft carrier Valley Forge along the east coast of Korea, she conducted bombardment missions from 12 to 26 October in the Chongjin and Tanchon areas, and at Wonsan where she again screened carriers eastward of Wonsan.[3]

MacArthur's amphibious landings at Incheon had severed the North Korean Army's supply lines; as a result, North Korea's army had begun a lengthy retreat from South Korea into North Korea. This retreat was closely monitored by the People's Republic of China (PRC), out of fear that the UN offensive against Korea would create a US-backed enemy on China's border, and out of concern that the UN offensive in Korea could evolve into a UN war against China. The latter of these two threats had already manifested itself during the Korea War: U.S. F-86 Sabres on patrol in "MiG Alley" frequently crossed into China while pursuing Communist MiGs operating out of Chinese airbases.[16]

_in_heavy_seas_c1951.jpg)

Moreover, there was talk among the U.N. commanders—notably General Douglas MacArthur—about a potential campaign against the People's Republic of China. In an effort to dissuade UN forces from completely overrunning North Korea, the People's Republic of China issued diplomatic warnings that they would use force to protect North Korea, but these warnings were not taken seriously for a number of reasons, among them the fact that China lacked air cover to conduct such an attack.[17][18] This changed abruptly on 19 October 1950, when the first of an eventual total of 380,000 People's Liberation Army soldiers under the command of General Peng Dehuai crossed into North Korea, launching a full-scale assault against advancing U.N. troops. The PRC offensive caught the UN completely by surprise; UN forces realized they would have to fall back, and quickly executed an emergency retreat. UN assets were shuffled in order to cover this retreat, and as part of the force tasked with covering the UN retreat Missouri was moved into Hungnam on 23 December to provide gunfire support about the Hungnam defense perimeter until the last UN troops, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, were evacuated by way of the sea on 24 December 1950.[3]

Missouri conducted additional operations with carriers and shore bombardments off the east coast of Korea until 19 March 1951. She arrived at Yokosuka on 24 March, and 4 days later was relieved of duty in the Far East. She departed Yokosuka on 28 March, and upon arrival at Norfolk on 27 April became the flagship of Rear Admiral James L. Holloway, Jr., commander, Cruiser Force, Atlantic Fleet. During the summer of 1951, she engaged in two midshipman training cruises to northern Europe. Under the command of Captain John Sylvester, Missouri entered Norfolk Naval Shipyard 18 October 1951 for an overhaul, which lasted until 30 January 1952.[3]

Following winter and spring training out of Guantanamo Bay, Missouri visited New York, then set course from Norfolk on 9 June 1952 for another midshipman cruise. She returned to Norfolk on 4 August and entered Norfolk Naval Shipyard to prepare for a second tour in the Korean combat zone.[3]

Missouri stood out of Hampton Roads on 11 September 1952 and arrived at Yokosuka on 17 October. Vice Admiral Joseph J. Clark, commander of the 7th Fleet, brought his staff onboard on 19 October. Her primary mission was to provide seagoing artillery support by bombarding enemy targets in the Chaho-Tanchon area, at Chongjin, in the Tanchon-Sonjin area, and at Chaho, Wonsan, Hamhung, and Hungnam during the period 25 October through 2 January 1953.[3]

Missouri put into Incheon on 5 January 1953 and sailed thence to Sasebo, Japan. General Mark W. Clark, Commander in Chief, U.N. Command, and Admiral Sir Guy Russell, Royal Navy Commander-in-Chief, Far East Fleet, visited the battleship on 23 January. In the following weeks, Missouri resumed "Cobra" patrol along the east coast of Korea to support troops ashore. Repeated bombardment of Wonsan, Tanehon, Hungnam, and Kojo destroyed main supply routes along the eastern seaboard of Korea.[3]

The last bombardment mission by Missouri was against the Kojo area on 25 March. On 26 March, her commanding officer—Captain Warner R. Edsall—suffered a fatal heart attack while conning her through the submarine net at Sasebo. She was relieved as the 7th Fleet flagship on 6 April by her older sister New Jersey.[3]

Missouri departed Yokosuka on 7 April and arrived at Norfolk on 4 May to become flagship for Rear Admiral E. T. Woolridge, commander, Battleships-Cruisers, Atlantic Fleet, on 14 May. She departed on 8 June on a midshipman training cruise, returned to Norfolk on 4 August, and was overhauled in Norfolk Naval Shipyard from 20 November 1953 to 2 April 1954. As the flagship of Rear Admiral R. E. Kirby, who had relieved Admiral Woolridge, Missouri departed Norfolk on 7 June as flagship of the midshipman training cruise to Lisbon and Cherbourg. During this voyage Missouri was joined by the other three battleships of her class, New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Iowa, the only time the four ships sailed together.[19] She returned to Norfolk on 3 August and departed on 23 August for inactivation on the West Coast. After calls at Long Beach and San Francisco, Missouri arrived in Seattle on 15 September. Three days later she entered Puget Sound Naval Shipyard where she was decommissioned on 26 February 1955, entering the Bremerton group, Pacific Reserve Fleet.[3][20]

Deactivation

Upon arrival in Bremerton, west of Seattle, Missouri was moored at the last pier of the reserve fleet berthing. She served as a popular tourist attraction, logging about 250,000 visitors per year,[21] who came to view the "surrender deck" where a bronze plaque memorialized the spot (35.3547°N 139.76°E) in Tokyo Bay where Japan surrendered to the Allies, and the accompanying historical display that included copies of the surrender documents and photos.[20] A small cottage industry grew in the civilian community just outside the gates, selling souvenirs and other memorabilia. Nearly thirty years passed before Missouri returned to active duty.[3]

Reactivation (1984 to 1990)

Under the Reagan Administration's program to build a 600-ship Navy, led by Secretary of the Navy John F. Lehman, Missouri was reactivated and towed by the salvage ship Beaufort to the Long Beach Naval Yard in the summer of 1984 to undergo modernization in advance of her scheduled recommissioning.[3][21] In preparation for the move, a skeleton crew of 20 spent three weeks working 12- to 16-hour days preparing the battleship for her tow.[22] During the modernization Missouri had her obsolete armament removed: 20 mm and 40 mm anti-aircraft guns, and four of her ten 5-inch (127 mm) gun mounts.[23]

.jpg)

Over the next several months, the ship was upgraded with the most advanced weaponry available; among the new weapons systems installed were four Mk 141 quad cell launchers for 16 RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles, eight Mk 143 Armored Box Launcher mounts for 32 BGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missiles, and a quartet of Phalanx Close In Weapon System Gatling guns for defense against enemy anti-ship missiles and enemy aircraft.[23] Also included in her modernization were upgrades to radar and fire control systems for her guns and missiles, and improved electronic warfare capabilities.[23] During the modernization Missouri's 800 lb (360 kg) bell, which had been removed from the battleship and sent to Jefferson City, Missouri for sesquicentennial celebrations in the state, was formally returned to the battleship in advance of her recommissioning.[24] Missouri was formally recommissioned in San Francisco on 10 May 1986. "This is a day to celebrate the rebirth of American sea power," Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger told an audience of 10,000 at the recommissioning ceremony, instructing the crew to "listen for the footsteps of those who have gone before you. They speak to you of honor and the importance of duty. They remind you of your own traditions."[25] Also present at the recommissioning ceremony was Missouri governor John Ashcroft, U.S. Senator Pete Wilson, Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, San Francisco mayor Dianne Feinstein. Margaret Truman, (who christened the ship in 1943) gave a short speech especially aimed at the ship's crew, which ended with "now take care of my baby." Her remarks were met with rounds of applause from the crew.[26]

Four months later Missouri departed from her new home port of Long Beach for an around-the-world cruise, visiting Pearl Harbor Hawaii; Sydney, Hobart, and Perth, Australia; Diego Garcia; the Suez Canal; Istanbul, Turkey; Naples, Italy; Rota, Spain; Lisbon, Portugal; and the Panama Canal. Missouri became the first American battleship to circumnavigate the globe since Theodore Roosevelt's "Great White Fleet" 80 years before—a fleet which included the first battleship named USS Missouri (BB-11).[3]

In 1987, Missouri was outfitted with 40 mm grenade launchers and 25 mm chain guns and sent to take part in Operation Earnest Will, the escorting of reflagged Kuwaiti oil tankers in the Persian Gulf.[27] These smaller-caliber weapons were installed due to the threat of Iranian-manned, Swedish-made Boghammar cigarette boats operating in the Persian Gulf at the time.[28] On 25 July, the ship departed on a six-month deployment to the Indian Ocean and North Arabian Sea. She spent more than 100 continuous days at sea in a hot, tense environment. As the centerpiece for Battlegroup Echo, Missouri escorted tanker convoys through the Strait of Hormuz, keeping her fire control system trained on land-based Iranian Silkworm missile launchers.[29]

Missouri returned to the United States via Diego Garcia, Australia, and Hawaii in early 1988. Several months later, Missouri's crew again headed for Hawaiian waters for the Rim of the Pacific (RimPac) exercises, which involved more than 50,000 troops and ships from the navies of Australia, Canada, Japan, and the United States. Port visits in 1988 included Vancouver and Victoria in Canada, San Diego, Seattle, and Bremerton.[3]

In the early months of 1989, Missouri was in the Long Beach Naval Shipyard for routine maintenance. On 1 July 1989, while berthed at Pier D, the music video for Cher's "If I Could Turn Back Time" was filmed aboard Missouri and featured the ship's crew. A few months later she departed for Pacific Exercise (PacEx) '89, where she and New Jersey performed a simultaneous gunfire demonstration for the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Nimitz. The highlight of PacEx was a port visit in Pusan, Republic of Korea. In 1990, Missouri again took part in the RimPac Exercise with ships from Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea, and the U.S.[3]

Gulf War (January–February 1991)

On 2 August 1990 Iraq, led by President Saddam Hussein, invaded Kuwait. In the middle of the month U.S. President George H. W. Bush, in keeping with the Carter Doctrine, sent the first of several hundred thousand troops, along with a strong force of naval support, to Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf area to support a multinational force in a standoff with Iraq.

Missouri's scheduled four-month Western Pacific port-to-port cruise set to begin in September was canceled just a few days before the ship was to leave. She had been placed on hold in anticipation of being mobilized as forces continued to mass in the Middle East. Missouri departed on 13 November 1990 for the troubled waters of the Persian Gulf. She departed from Pier 6 at Long Beach, with extensive press coverage, and headed for Hawaii and the Philippines for more work-ups en route to the Persian Gulf. Along the way she made stops at Subic Bay and Pattaya Beach, Thailand, before transiting the Strait of Hormuz on 3 January 1991. During subsequent operations leading up to Operation Desert Storm, Missouri prepared to launch Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAMs) and provide naval gunfire support as required.[3]

Missouri fired her first Tomahawk missile at Iraqi targets at 01:40 am on 17 January 1991, followed by 27 additional missiles over the next five days.[3]

On 29 January, the Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate Curts led Missouri northward, using advanced mine-avoidance sonar. In her first naval gunfire support action of Desert Storm she shelled an Iraqi command and control bunker near the Saudi border, the first time her 16 in (406 mm) guns had been fired in combat since March 1953 off Korea.[30] The battleship bombarded Iraqi beach defenses in occupied Kuwait on the night of 3 February, firing 112 16 in (406 mm) rounds over the next three days until relieved by Wisconsin. Missouri then fired another 60 rounds off Khafji on 11–12 February before steaming north to Faylaka Island. After minesweepers cleared a lane through Iraqi defenses, Missouri fired 133 rounds during four shore bombardment missions as part of the amphibious landing feint against the Kuwaiti shore line the morning of 23 February.[3] The heavy pounding attracted Iraqi attention; in response to the battleship's artillery strike, the Iraqis fired two HY-2 Silkworm missiles at the battleship, one of which missed.[3] The other missile was intercepted by a GWS-30 Sea Dart missile launched from the British air defence destroyer HMS Gloucester[3] within 90 seconds and crashed into the sea roughly 700 yd (640 m) in front of Missouri.[31]

During the campaign, Missouri was involved in a friendly fire incident with the Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate Jarrett. According to the official report, on 25 February, Jarrett's Phalanx CIWS engaged the chaff fired by Missouri as a countermeasure against enemy missiles, and stray rounds from the firing struck Missouri, one penetrating through a bulkhead and becoming embedded in an interior passageway of the ship. Another round struck the ship on the forward funnel, passing completely through it. One sailor aboard Missouri was struck in the neck by flying shrapnel and suffered minor injuries. Those familiar with the incident are skeptical of this account, however, as Jarrett was reportedly over 2 mi (3.2 km) away at the time and the characteristics of chaff are such that a Phalanx would not normally regard it as a threat and engage it.[32] There is no dispute that the rounds that struck Missouri did come from Jarrett, and that it was an accident. There was suspicion that a Phalanx operator on Jarrett may have accidentally fired off a few rounds manually, although there is no supporting evidence.[33][34]

During the operation, Missouri also assisted coalition forces engaged in clearing Iraqi naval mines in the Persian Gulf. By the time the war ended, Missouri had destroyed at least 15 naval mines.[31]

With combat operations out of range of the battleship's weapons on 26 February, Missouri had fired a total 783 rounds of 16 in (406 mm) shells and launched 28 Tomahawk cruise missiles during the campaign,[35] and commenced to conduct patrol and armistice enforcement operations in the northern Persian Gulf until sailing for home on 21 March. Following stops at Fremantle and Hobart, Australia, the warship visited Pearl Harbor before arriving home in April. She spent the remainder of the year conducting type training and other local operations, the latter including 7 December "voyage of remembrance" to mark the 50th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. During that ceremony, Missouri hosted President George H. W. Bush, the first such presidential visit for the warship since Harry S. Truman's in September 1947.[3]

Museum ship (1998 to present)

_begins_its_2-mile_journey_back_to_Ford_Island.jpg)

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s and the absence of a perceived threat to the United States came drastic cuts in the defense budget, and the high cost of maintaining and operating battleships as part of the United States Navy's active fleet became uneconomical; as a result, Missouri was decommissioned on 31 March 1992 at Long Beach, California, after 16 total years of active service.[1] Her last commanding officer, Captain Albert L. Kaiss, wrote in the ship's final Plan of the Day:

Our final day has arrived. Today the final chapter in battleship Missouri's history will be written. It's often said that the crew makes the command. There is no truer statement ... for it's the crew of this great ship that made this a great command. You are a special breed of sailors and Marines and I am proud to have served with each and every one of you. To you who have made the painful journey of putting this great lady to sleep, I thank you. For you have had the toughest job. To put away a ship that has become as much a part of you as you are to her is a sad ending to a great tour. But take solace in this—you have lived up to the history of the ship and those who sailed her before us. We took her to war, performed magnificently and added another chapter in her history, standing side by side our forerunners in true naval tradition. God bless you all.

— Captain Albert L. Kaiss[25]

Missouri returned to be part of the United States Navy reserve fleet at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, Bremerton, Washington, until 12 January 1995, when she was struck from the Naval Vessel Register. She remained in Bremerton, but was not open to tourists as she had been from 1957 to 1984. In spite of attempts by citizens' groups to keep her in Bremerton and be re-opened as a tourist site, the U.S. Navy wanted to pair a symbol of the end of World War II with one representing its beginning.[37] On 4 May 1998, Secretary of the Navy John H. Dalton signed the donation contract that transferred her to the nonprofit USS Missouri Memorial Association (MMA) of Honolulu, Hawaii. She was towed from Bremerton on 23 May to Astoria, Oregon, where she sat in fresh water at the mouth of the Columbia River to kill and drop the saltwater barnacles and sea grasses that had grown on her hull in Bremerton,[31] then towed across the eastern Pacific, and docked at Ford Island, Pearl Harbor on 22 June, just 500 yd (460 m) from the Arizona Memorial.[25] Less than a year later, on 29 January 1999, Missouri was opened as a museum operated by the MMA.

Originally, the decision to move Missouri to Pearl Harbor was met with some resistance. The National Park Service expressed concern that the battleship, whose name has become synonymous with the end of World War II, would overshadow the battleship Arizona, whose dramatic explosion and subsequent sinking on 7 December 1941 has since become synonymous with the attack on Pearl Harbor.[38] To help guard against this impression Missouri was placed well back from and facing the Arizona Memorial, so that those participating in military ceremonies on Missouri's aft decks would not have sight of the Arizona Memorial. The decision to have Missouri's bow face the Arizona Memorial was intended to convey that Missouri watches over the remains of Arizona so that those interred within Arizona's hull may rest in peace.[39]

A gun from Missouri is paired with a gun formerly on Arizona at the Wesley Bolin Memorial Plaza just east of the Arizona State Capitol complex in downtown Phoenix, Arizona. It is part of a memorial representing the start and end of the Pacific War for the United States.[40]

Missouri was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on 14 May 1971 for hosting the signing of the instrument of Japanese surrender that ended World War II.[38] She is not eligible for designation as a National Historic Landmark because she was extensively modernized in the years following the surrender.[39]

On 14 October 2009, Missouri was moved from her berthing station on Battleship Row to a drydock at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard to undergo a three-month overhaul. The work, priced at $18 million, included installing a new anti-corrosion system, repainting the hull, and upgrading the internal mechanisms. Drydock workers reported that the ship was leaking at some points on the starboard side.[41] The repairs were completed the first week of January 2010 and the ship was returned to her berthing station on Battleship Row on 7 January 2010. The ship's grand reopening occurred on 30 January.[42]

Appearances in popular culture

Missouri was central to the plot of the film Under Siege, and the ship was prominently featured in another movie, Battleship. As Missouri has not moved under her own power since 1992, shots of the ship at sea were obtained with the help of three tugboats.[43] The music video for Cher's "If I Could Turn Back Time" was also filmed aboard the Missouri. The U.S. Navy, which had granted permission to shoot the video there, was unhappy with the sexual nature of the performance.[44]

Awards

Missouri received three battle stars for her service in World War II, five for her service during the Korean War, and three for her service during the Gulf War.[39] Missouri also received numerous awards for her service in World War II, Korea, and the Persian Gulf.[45]

- 2017 Preservation Honor Award from the Historic Hawai‘i Foundation[46]

- Historic Naval Ships Association Awards [47]

- 2001 Russell Booth Award

- 2011 Henry A. Vadnais, Jr. Award

- 2011 HNSA Educator Award

- 2016 HNSA Educator Award

| Combat Action Ribbon | |||

| Navy Unit Commendation w/1 service star | Navy Meritorious Unit Commendation | Navy E Ribbon w/ Wreathed Battle E device | China Service Medal |

| American Campaign Medal | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal w/ 3 battle stars | World War II Victory Medal | Navy Occupation Service Medal |

| National Defense Service Medal w/ 1 service star | Korean Service Medal w/ 5 battle stars | Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal | Southwest Asia Service Medal w/ 2 service stars |

| Navy Sea Service Deployment Ribbon w/ 2 service stars | Korean Presidential Unit Citation | United Nations Korea Medal | Kuwait Liberation Medal (Saudi Arabia) |

See also

- List of broadsides of major World War II ships

- List of museum ships

- SMS Schleswig-Holstein, the former Kaiserliche Marine ship that fired World War II's first shots in Europe

- U.S. Navy memorials

- U.S. Navy museums (and other battleship museums)

Notes

- At the time Missouri was commissioned two other Iowa-class battleships—Illinois and Kentucky—were under construction, and the United States Navy had commissioned plans for the Montana-class battleships; however, Illinois and Kentucky were canceled before their construction had been completed, and the Montana's were suspended and ultimately canceled before any of their hulls were laid down.

- Internationally, there were two other battleships that came after Missouri: the British battleship HMS Vanguard, the final battleship constructed by the Royal Navy, and the French battleship Jean Bart.

- Wisconsin was commissioned on 16 April 1944,[2] while Missouri was commissioned on 11 June 1944.[1]

- William F. Halsey held the rank of a four star admiral from November 1942. In December 1945, four months after the official surrender of the Japanese, he was promoted to the rank of fleet admiral and awarded his fifth star.[8]

- American Secretary of State Dean Acheson had told Congress on 20 June that no war was likely.

References

- "Missouri (BB 63)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy. 19 July 2002. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- "Wisconsin (BB 64)". Naval Vessel Register. United States Navy. 20 March 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- "USS Missouri". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. United States Navy. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- Johnston & McAuley (2002), p. 120.

- Friedman, Norman (1986). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-715-1. OCLC 12214729.

- "Battleship Missouri Ceremony to Honor Ship's First Commander, Captain William M. Callaghan, 12 April" (Press release). USS Missouri Memorial Association. 19 March 2001. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2006.

- BobMeade (23 June 2007), USS Missouri - Starbord rail dent from Kamikaze attack, retrieved 29 October 2019

- "William Frederick Halsey, Jr". Naval History and Heritage Command. 8 April 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Missouri's place in history". All Hands. No. 822. Alexandria, VA: United States Navy. September 1985. p. 16.

- Tsutsumi, Cheryl Chee (26 August 2007). "Hawaii's Back Yard: Mighty Mo memorial re-creates a powerful history". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Murray, Stuart S. "Reminiscences of the Surrender of Japan and the End of World War II". USS Missouri Memorial Association. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Doehring, Thoralf. "USS Missouri (BB-63): Accidents aboard USS Missouri". Navysite.de. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- Close, Robert A. (Cmdr). "Helo Operations". U.S. Naval Academy Alumni Association & Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Stillwell, Paul (February 1999). "USS Missouri: Served in World War II and Korean War". American History. ISSN 1076-8866. OCLC 30148811. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- Adamski, Mary (9 August 1998). "Mighty Mo anchors $500,000 donation". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- "MIG Alley". Dogfights. Season 1. Episode 1. 3 November 2006. The History Channel.

- Schnabel, James F.; Appleman, Roy Edgar; United States Department of the Army, Office of Military History (1961–72). United States Army in the Korean War. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army. p. 212. ISBN 1-4102-2485-6. OCLC 81433331.

- Donovan, Robert J. (1982). Tumultuous Years: The Presidency of Harry S. Truman, 1949–1953. New York: Norton. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-393-01619-2. OCLC 8345640.

- Kaplan (2004), p. 166.

- "Missouri quiet now 29 years after war ended". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. Associated Press. 2 September 1974. p. 7.

- Camden, Jim (13 March 1984). "Big ship in midst of fight". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. p. A6.

- Weissleder, Bob (November 1984). "Mighty Mo Rejoins Fleet". All Hands. No. 813. Alexandria, VA: United States Navy. pp. 26–28.

- "BB-61 Iowa-class specifications". Federation of American Scientists. 21 October 2000. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- "Missouri bell returned". All Hands. No. 822. Alexandria, VA: United States Navy. September 1985. p. 16.

- "United States Navy Battleships: USS Missouri (BB-63)". The Battleships. United States Navy Office of Information. 24 April 2000. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 15 December 2006.

- "USS Missouri". ABC News. 10 May 1986. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Poyer, Joe (1991). "Are These the Last Battleships?". In Lightbody, Andy; Blaine, Taylor (eds.). Battleships at War: America's Century Long Romance with the Big Guns of the Fleet. Canoga Park, California: Challenge Publications, Inc. pp. 50–53.

- "Frequently asked questions aboard the Missouri". USS Missouri Memorial Association. 2004. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- Chernesky, J. J. (October 1987). "Command History, Calendar Year 1987, (OPNAV Report Symbol 5750-1)". USS Missouri Memorial Association. p. 2. Archived from the original on 27 May 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- United States. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. (15 May 1991). "V: "Thunder And Lightning"- The War With Iraq". The United States Navy in "Desert Shield" / "Desert Storm". Washington, D.C.: United States Navy. OCLC 25081170. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- Kakesako, Gregg K. (15 June 1998). "Pride & Glory". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- "Lead Report #14246". Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses, Department of Defense. 23 January 1998. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- "TAB H – Friendly-fire Incidents". Environmental Exposure Report: Depleted Uranium in the Gulf (II). Office of the Special Assistant for Gulf War Illnesses, Department of Defense. Washington, D.C. 2000. OCLC 47168115. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "USS Jarrett FFG 33 guided missile frigate". Seaforces. 2 March 2012. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Polmar (2001), p. 129.

- "Battleship Photo Index BB-63 USS MISSOURI". www.navsource.org. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Friedrich, Ed (4 May 2008). "Letting Go of the Mighty Mo". Kitsap Sun. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- Kakesako, Gregg K. (15 October 1997). "Will "Mighty Mo" be too much?". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- Peck, Rand (24 November 2006). "Next stop... Mighty Mo, the USS Missouri (BB-63)". A Life Aloft. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- "Phoenix, Arizona – USS Arizona Anchor and Mast". Roadside America.com. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Nakaso, Dan (15 October 2009). "The Mighty Move". The Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "Battleship Returns To Pearl Harbor". Philadelphia Inquirer. Associated Press. 4 January 2010.

- Wickman, Forest (21 May 2012). "Fact-Checking Battleship: Could We Really Revive the "Mighty Mo"?". Slate. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Marks, Craig; Tannenbaum, Rob (2011). I want my MTV: The uncensored story of the music video revolution. New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-1-101-52641-5.

- "Missouri Ribbon Bar". USS Missouri Memorial Association. Archived from the original on 13 March 2004. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- https://ussmissouri.org/news/battleship-missouri-memorial-earns-2017-preservation-honor-award

- https://www.hnsa.org/about-us/awards/

Bibliography

- Johnston, Ian; McAuley, Rob (2002). The Battleships. London: Channel 4. ISBN 0-7522-6188-6.

- Kaplan, Philip (2004). Battleship. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 1-85410-902-2.

- Polmar, Norman (2001). The Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-656-6.

- Naval Historical Foundation (2004). The Navy. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 0-7607-6218-X.

- Man of War: Log of the United States Heavy Cruiser Louisville. The Dunlap Printing Co. 1946.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Further reading

- Butler, John A. (1995). Strike Able-Peter: The Stranding and Salvage of the USS Missouri. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-094-0.

- Muir, Malcolm (1987). The Iowa Class Battleships. New York: Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8069-8338-8.

- Reilly, John C., Jr. (1989). Operational Experience of Fast Battleships: World War II, Korea, Vietnam. Washington DC: Naval Historical Center. ASIN B000KZP9LA.

- Sumrall, Robert F. (1988). Iowa Class Battleships: Their Design, Weapons, and Equipment. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-298-2.

- Newell, Gordon; Smith, Allan E. Mighty Mo: The Biography of the Last Battleship. Seattle, Washington: Superior Publishing Company. LCCN 72-87802.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Battleship Missouri Memorial museum website

- Photo gallery at Naval Historical Center

- USS Missouri (BB-63) at Historic Naval Ships Association

- Photo gallery of USS Missouri at NavSource Naval History

- nvr.navy.mil: USS Missouri

- navysite.de: USS Missouri

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. HI-62, "USS Missouri, Battleship Row, Ford Island, Pearl City, Honolulu County, HI", 6 measured drawings, 21 data pages