Samosa

A samosa (/səˈmoʊsə/) is a fried or baked pastry with a savoury filling, such as spiced potatoes, onions, peas, cheese, beef and other meats, or lentils. It may take different forms, including triangular, cone, or half-moon shapes, depending on the region.[2][3][4] The Indian style, often accompanied by a chutney, is probably the most widely known of a broad family of recipes from Africa to China, which have origins in medieval times or earlier.[2] Samosas are a popular entrée, appetizer, or snack in the local cuisines of the Indian subcontinent, Western Asia, Southeast Asia, the Mediterranean, and Africa. Due to emigration and cultural diffusion from these areas, samosas today are often prepared in other regions.

Samosas with chutney and green chilies in West Bengal, India. | |

| Alternative names | Samoosa, samusa[1] |

|---|---|

| Type | Snack |

| Course | Entrée, snack |

| Region or state | South Asia, Southeast Asia, Middle East, North Africa, Horn of Africa, West Africa, East Africa |

| Serving temperature | Hot |

| Main ingredients | flour, vegetables (e.g. potatoes, onions, peas, lentils), spices, chili peppers, cheese, meat (lamb, beef, or chicken) |

Etymology

The word samosa can be traced to the Persian word sanbosag (Persian: سنبوساگ).[5] The pastry's name in other countries can also derive from this root, such as the crescent-shaped sanbusak or sanbusaj in the Arab world, sambosa in Afghanistan, shingara (Bengali: সিঙ্গারা /সমোসা) in Bengal,Shingada (Odia:ସିଙ୍ଗଡା) in Odisha,samosa (Urdu: سموسہ) in Pakistan, samosa (Hindi: समोसा) in India, (Sindhi: سمبوسو Samboso/sambosa), samboosa in Tajikistan, sambosa or samosa in Madagascar, samsa by Turkic-speaking nations, sambusa (Amharic: ሳምቡሳ) by the Amharas of Ethiopia, sambuus by Somalis of Somalia, Djibouti, Somali Region of Ethiopia and North Eastern Province of Kenya, samsa in Tamil Nadu (India), chamuça in Goa (India), Mozambique and Portugal. While they are currently referred to as sambusak in the Arabic-speaking world, Medieval Arabic recipe books sometimes spell it sambusaj.[6] The word samoosa is used in South Africa.[7][8]

History

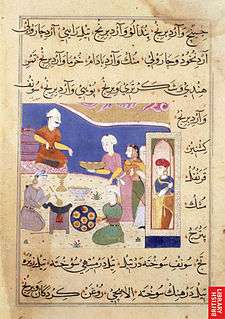

The samosa originated in the Middle East and Central Asia.[9] It then spread to Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and elsewhere. The term samosa and its variants cover a family of pastries and dumplings popular from north-eastern Africa to western China. The samosa spread to the Indian subcontinent, following the invasion of the Central Asian Turkic dynasties in the region.[10] A praise of samosa (as sanbusaj) can be found in a 9th-century poem by the Persian poet Ishaq al-Mawsili. Recipes for the dish are found in 10th–13th-century Arab cookery books, under the names sanbusak, sanbusaq, and sanbusaj, all of which derive from the Persian word sanbosag. In Iran, the dish was popular until the 16th century, but by the 20th century, its popularity was restricted to certain provinces (such as the sambusas of Larestan).[2] Abolfazl Beyhaqi (995-1077), an Iranian historian, mentioned it in his history, Tarikh-e Beyhaghi.[11]

Central Asian samsa were introduced to the Indian subcontinent in the 13th or 14th century by traders from Central Asia.[5] Amir Khusro (1253–1325), a scholar and the royal poet of the Delhi Sultanate, wrote in around 1300 CE that the princes and nobles enjoyed the "samosa prepared from meat, ghee, onion, and so on".[12] Ibn Battuta, a 14th-century traveler and explorer, describes a meal at the court of Muhammad bin Tughluq, where the samushak or sambusak, a small pie stuffed with minced meat, almonds, pistachios, walnuts, and spices, was served before the third course, of pulao.[13] Nimmatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, a medieval Indian cookbook started for Ghiyath al -Din Khalji, the ruler of the Malwa Sultanate in central India, mentions the art of making samosa.[14] The Ain-i-Akbari, a 16th-century Mughal document, mentions the recipe for qutab, which it says, "the people of Hindustan call sanbúsah".[15]

Regional varieties

Indian subcontinent

India

The samosa is made with all-purpose flour locally known as maida shell stuffed with some filling, generally a mixture of mashed boiled potato, onions, green peas, lentils, paneer, spices and green chilli, or fruits. It can be vegetarian or non-vegetarian, depending on the filling. The entire pastry is then deep-fried in vegetable oil or rarely ghee to a golden brown color. It is served hot and is often eaten with fresh green chutney, such as mint, coriander, or tamarind. It can also be prepared as a sweet form, rather than as a savoury one. Samosas are often served in chaat, along with the traditional accompaniments of either chick pea or white pea preparation, garnished with yogurt, tamarind and green chutney, chopped onions, coriander, and chaat masala

In Delhi, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Uttarakhand, a bigger version of the samosa with a spicy filling of masala potatoes, peas, crushed green chillies, cheese, and even dried fruits, as well as other variations, is quite popular. This samosa is bigger compared to other Indian and foreign variants.

In Odisha, West Bengal, and Jharkhand, shingadas (the East Indian version of samosas) are popular snacks. They are found almost everywhere. They are a bit smaller compared to those in other parts of India, and the filling mainly consists of boiled and diced potato, along with of other ingredients. They are wrapped in a thin sheet of dough (made of all purpose flour) and fried. Good shingaras are distinguished by flaky textures, almost as if they are made with a savoury pie crust.

Usually, Samosas are deep-fried to a golden brown colour in vegetable oil. They are served hot and consumed with ketchup or chutney, such as mint, coriander, or tamarind, or are served in chaat, along with the traditional accompaniments of yogurt, chutney, chopped onions, coriander, and chaat masala. Usually, shingaras are eaten at tea time as a snack. They can also be prepared in a sweet form, rather than as a savoury one. Bengali shingaras tend to be triangular, filled with potato, peas, onions, diced almonds, or other vegetables, and are more heavily fried and crunchier than either shingara or their Indian samosa cousins. Fulkopir shingara (shingara filled with cauliflower mixture) is another very popular variation. In Bengal, there are non-vegetarian varieties of shingara called mangsher shingara (mutton shingara) and macher shingara (fish shingara). There are also sweeter versions, such as narkel er shingara (coconut shingara), as well as others filled with khoya and dipped in sugar syrup.

In Hyderabad, India, a smaller version of the samosa with a thicker pastry crust and mince-meat filling, referred to as lukhmi, is consumed, as is another variation with an onion filling.

In the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, samosas are slightly different, in that they are folded in a different way, much more like Portuguese chamuças, with a different style pastry. The filling also differs, typically featuring mashed potatoes with spices, fried onions, peas, carrots, cabbage, curry leaves, green chillies, etc. It is mostly eaten without chutney. Samosas in South India are made in different sizes, and fillings are greatly influenced by the local food habits. It can include many variety of fillings, such as meats and vegetables.

Nowadays, another version of samosa (noodle samosa) is also very popular in India. It is a samosa filled with noodles and some raw or cooked vegetables as well,

Bangladesh

.jpg)

Both flat-shaped (triangular) and full-shaped (tetrahedron/triangular pyramid) samosas are popular snacks in Bangladesh. A Bengali version of the full-shaped samosa is called a সিঙাড়া (shingara) and is normally smaller than the standard variety. The shingara is usually filled with pieced potatoes, vegetables, nuts etc. However, shingaras filled with beef liver are very popular in some parts of the country. The flat-shaped samosa is called a somosa or somucha, and is usually filled with onions and minced meat.

Nepal

Samosas are called singadas in the eastern zone of Nepal; the rest of the country calls it samosa. As in India, it is a very popular snack in Nepalese cuisine. Vendors sell the dish in various markets and restaurants.

Pakistan

Samosas of various types are available all over Pakistan. In general, most samosa varieties sold in the southern Sindh province and in the eastern Punjab, especially the city of Lahore, are spicier and mostly contain vegetable or potato-based fillings. However, the samosas sold in the west and north of the country mostly contain minced meat-based fillings and are comparatively less spicy. The meat samosa contains minced meat (lamb, beef, or chicken) and are very popular as snack food in Pakistan.

In Pakistan, samosas of Karachi are famous for their spicy flavour, whereas samosas from Faisalabad are noted for being unusually large. Another distinct variety of samosa, available in Karachi, is called kaghazi samosa (Urdu: کاغذی سموسہ; "paper samosa" in English) due to its thin and crispy covering, which resembles a wonton or spring roll wrapper. Another variant, popular in Punjab, consists of samosas with side dishes of mashed spiced chickpeas, onions, and coriander leaf salad, as well as various chutneys to top the samosas. The samosas are a fried or baked pastry with a savoury filling, such as spiced potatoes, onions, peas, lentils, and minced meat (lamb, beef or chicken). Sweet samosas are also sold in the cities of Pakistan including Peshawar; these sweet samosas contain no filling and are dipped in thick sugar syrup.

Another Pakistani snack food, which is popular in Punjab, is known as "samosa chaat". This is a combination of a crumbled samosa, along with spiced chickpeas (channa chaat), yogurt, and chutneys. Alternatively, the samosa can be eaten on its own with a side of chutney.

In Pakistan, samosas are a staple iftaar food for many Pakistani families, during the month of Ramzan.

Maldives

The types and varieties of samosa made in Maldivian cuisine are known as bajiyaa. They are filled with a mixture including fish or tuna and onions.[16]

Southeast Asia

Burma

Samosas are called samusas in Burmese, and are an extremely popular snack in Burma.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, samosas are locally known as samosa, filled with potato, cheese, curry, rousong or noodles as adapted to local taste. It usually served as snack with sambal. Samosa is almost similar to Indonesian pastel, panada and epok-epok.

Africa

Swahili Coast

Sambusas are also a key part of Swahili food - often seen in Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda.

Somalia and Djibouti

Samosas are a staple of local cuisine in the Horn of Africa countries of Djibouti and Somalia, where they are known as sambuus. They are traditionally made with a thinner pastry dough, similar to egg roll wraps, and stuffed with ground beef. While they can be eaten any time of the year, they are usually reserved for special occasions.

South Africa

Called samoosas in South Africa,[7][8] they tend to be smaller than Indian variants,[17] and form part of South African Indian and Cape Malay cuisine.

West Africa

Samosas also exist in West African countries such as Ghana where they are a common street food and Senegal where they are known as fataya.

Middle East

Arab countries

Sambousek (Arabic: سمبوسك) are usually filled with either meat, onion, and pine nuts, or cheese.

Israel

In Israel, a sambusaq (Hebrew: סמבוסק) may be a semicircular pocket of dough filled with mashed chickpeas, fried onions, and spices. Another variety is filled with meat, fried onions, parsley, spices, and pine nuts, which is sometimes mixed with mashed chickpeas and breakfast version with feta or tzfat cheese and za'atar. Other common fillings are potato and "pizza", which is somewhat similar to Calzone. It is associated with Mizrahi Jewish cuisine, and various recipes have been brought to Israel by Jewish migrants from other countries in the Middle East and Africa.[18] According to food historian Gil Marks, sambusak has been a traditional part of the Sephardic Sabbath meal since the 13th century in Spain.[19]

Portuguese-speaking regions

In Goa (India) and Portugal, samosas are known as chamuças. They are usually filled with chicken, beef, pork, lamb or vegetables, and generally served quite hot. Samosas are an integral part of Goan and Portuguese cuisine, where they are a common snack.

A samosa-inspired snack is also very common in Brazil, and relatively common in several former Portuguese colonies in Africa, including Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé and Príncipe, Angola, and Mozambique, where they are more commonly known as pastéis (in Brazil) or empadas (in Portuguese Africa; in Brazilian Portuguese, empada refers to a completely different snack, always baked, small in size, and in the form of an inverse pudding). They are related to the Hispanic empanada and to the Italian calzone.

English-speaking regions

Samosas are popular in the United Kingdom, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Uganda, South Africa, Rwanda, Kenya and Tanzania, and are also growing in popularity in Canada,[20][21] and the United States. They may be called samboosa or sambusac, but in South Africa, they are often called samoosa.[22] Frozen samosas are increasingly available from grocery stores in Australia, Canada, the United States,[23] and the United Kingdom.

Variations using filo,[24] or flour tortillas[25] are sometimes used.

See also

- Samsa

- Aloo pie

- Bourekas

- Chebureki

- Curry puff – Indonesian, Malaysian and Singaporean snack pie

- Fatayer – Arab cuisine

- List of stuffed dishes – Wikipedia list article

- Lukhmi

- Momo – Type of East and South Asian dumpling

- Pastel (food)

- Turnover

- Uchpuchmak

- Vada pav – Indian fast food item

- List of snack foods from the Indian subcontinent – Wikipedia list article

References

- "samosa". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

- Arnold P. Kaminsky; Roger D. Long (23 September 2011). India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic. ABC-CLIO. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-313-37462-3. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Reza, Sa’adia (18 January 2015). "Food's Holy Triangle". Dawn. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Lovely triangles Archived 8 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Hindustan Times, 23 August 2008.

- Rodinson, Maxime, Arthur Arberry, and Charles Perry. Medieval Arab cookery. Prospect Books (UK), 2001. p. 72.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Indigenous Culture, Education and Globalization: Critical Perspectives from Asia, Springer, 23 October 2015, p. 130, ISBN 9783662481592, archived from the original on 6 January 2019, retrieved 5 January 2019

- The Cambridge World History of Food, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 1151, ISBN 9780521402156,

Islam gave to Indian cookery its masterpiece dishes from the Middle East. These include pilau (from Iranian pollo and Turkish pilaf), samossa (Turkish sambussak), shir kurma (dates and milk), kebabs, sherbet, stuffed vegetables, oven bread, and confections (halvah).

- Beyhaqi, Abolfazl, Tarikh-e Beyhaghi, p. 132.

- Savoury temptations Archived 5 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Tribune, 5 September 2005.

- Regal Repasts Archived 7 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Jiggs Kalra and Dr Pushpesh Pant, India Today Plus, March 1999.

- M Bloom, Jonathan (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture Vol 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- Recipes for Dishes Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Ain-i-Akbari, by Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak. English tr. by Heinrich Blochmann and Colonel Henry Sullivan Jarrett, 1873–1907. Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, Volume I, Chapter 24, page 59. “10. Quṭáb, which the people of Hindústán call sanbúsah. This is made several ways. 10 s. meat; 4 s. flour; 2 s. g'hí; 1 s. onions; ¼ s. fresh ginger; ½ s. salt; 2 d. pepper and coriander seed; cardamum, cuminseed, cloves, 1 d. of each; ¼ s. of summáq. This can be cooked in 20 different ways, and gives four full dishes.”

- Xavier Romero-Frias, Eating on the Islands Archived 28 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Himal Southasian, Vol. 26 no. 2, pages 69-91 ISSN 1012-9804

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Gems in Israel: Sabich - The Alternate Israeli Fast Food". Archived from the original on 22 November 2013.

- Marks, Gil (2008). Olive Trees and Honey: A Treasury of Vegetarian Recipes from Jewish Communities Around the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 289–. ISBN 978-0-544-18750-4. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- "Lineups threaten to stall Fredericton's hot samosa market". CBC.ca. 30 January 2007. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Fox, Chris (29 July 2009). "Patel couldn't give her samosas away". The Daily Gleaner. p. A1. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- South African English is lekker! Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- Trader Joe's Fearless Flyer: Mini Vegetable Samosas Archived 12 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Fennel-Scented Spinach and Potato Samosas Archived 30 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- Potato Samosas Archived 18 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 6 February 2008.