Sindh

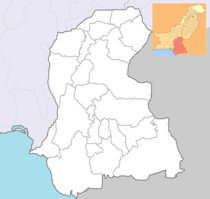

Sindh (/sɪnd/; Sindhi: سنڌ; Urdu: سندھ, pronounced [sɪnd̪ʰ]) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeast of the country, it is the historical home of the Sindhi people.[5][6] Sindh is the third largest province of Pakistan by area, and second largest province by population after Punjab. Sindh is bordered by Balochistan province to the west, and Punjab province to the north. Sindh also borders the Indian states of Gujarat and Rajasthan to the east, and Arabian Sea to the south. Sindh's landscape consists mostly of alluvial plains flanking the Indus River, the Thar desert in the eastern portion of the province closest to the border with India, and the Kirthar Mountains in the western part of Sindh.

Sindh سندھ سنڌ | |

|---|---|

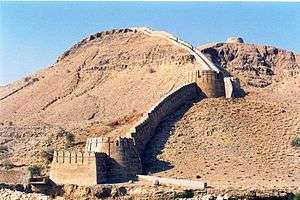

From top, left to right: Jinnah Mausoleum/Mazar-e-Quaid, Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Ranikot Fort, Faiz Mahal, Nagan Chowrangi flyover, Ayub Bridge adjacent to Lansdowne Bridge | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Mehran (Gateway), Bab-ul-Islam (Gateway of Islam) | |

.svg.png) Location of Sindh in Pakistan | |

| Coordinates: 26°21′N 68°51′E | |

| Country | |

| Established | |

| Capital | Karachi |

| Largest city | Karachi |

| Government | |

| • Type | Self-governing Province subject to the Federal government |

| • Body | Government of Sindh |

| • Governor | Imran Ismail |

| • Chief Minister | Syed Murad Ali Shah |

| • Chief Secretary | Mumtaz Ali Shah |

| • Legislature | Provincial Assembly |

| • High Court | Sindh High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 140,914 km2 (54,407 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 3rd |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 47,886,051 |

| • Rank | 2nd |

| • Density | 340/km2 (880/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Sindhi |

| Society | |

| • Languages | Sindhi, |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PST) |

| ISO 3166 code | PK-SD |

| Notable sports teams | Karachi Kings Karachi United Hyderabad Hawks Karachi Dolphins Karachi Zebras |

| HDI (2018) | 0.533 Low |

| Seats in National Assembly | 75 |

| Seats in Provincial Assembly | 168[3] |

| Divisions | 6 |

| Districts | 29 |

| Tehsils | 138 |

| Union Councils | 1108[4] |

| Website | sindh.gov.pk |

Sindh has Pakistan's second largest economy, while its provincial capital Karachi is Pakistan's largest city and financial hub, and hosts the headquarters of several multinational banks. Sindh is home to a large portion of Pakistan's industrial sector and contains two of Pakistan's commercial seaports, Port Bin Qasim and the Karachi Port. The remainder of Sindh has an agriculture based economy, and produces fruits, food consumer items, and vegetables for the consumption of other parts of the country.[7][8][9]

Sindh is known for its distinct culture which is strongly influenced by Sufism, an important marker of Sindhi identity for both Hindus (Sindh has Pakistan's highest percentage of Hindu residents)[10] and Muslims in the province.[11] Several important Sufi shrines are located throughout the province which attract millions of annual devotees.

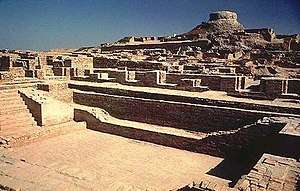

Sindh's capital, Karachi, Sindh is home to two UNESCO World Heritage Sites – the Historical Monuments at Makli, and the Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjodaro.[12]

Etymology

The word Sindh is derived from the Sanskrit term Sindhu (literally meaning "river"), which is a reference to Indus River.[13]

Southworth suggests that the name Sindhu is in turn derived from Cintu, the Proto-Dravidian word for date palm, a tree commonly found in Sindh.[14][15]

The official spelling "Sind" (from the Perso-Arabic pronunciation سند) was discontinued in 1988 by an amendment passed in Sindh Assembly.[16]

The Greeks who conquered Sindh in 325 BC under the command of Alexander the Great rendered it as Indós, hence the modern Indus. The ancient Iranians referred to everything east of the river Indus as hind.[17][18]

History

Prehistoric period

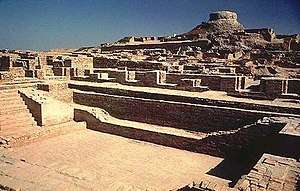

Sindh's first known village settlements date as far back as 7000 BC. Permanent settlements at Mehrgarh, currently in Balochistan, to the west expanded into Sindh. This culture blossomed over several millennia and gave rise to the Indus Valley Civilization around 3000 BC. The Indus Valley Civilization rivalled the contemporary civilizations of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia in size and scope, numbering nearly half a million inhabitants at its height with well-planned grid cities and sewer systems.

The primitive village communities in Balochistan were still struggling against a difficult highland environment, a highly cultured people were trying to assert themselves at Kot Diji. This was one of the most developed urban civilizations of the ancient world. It flourished between the 25th and 15th centuries BC in the Indus valley sites of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa. The people had a high standard of art and craftsmanship and a well-developed system of quasi-pictographic writing which remains un-deciphered. The ruins of the well planned towns, the brick buildings of the common people, roads, public baths and the covered drainage system suggest a highly organized community.[19]

According to some accounts, there is no evidence of large palaces or burial grounds for the elite. The grand and presumably holy site might have been the great bath, which is built upon an artificially created elevation.[20] This civilization collapsed around 1700 BC for reasons uncertain; the cause is hotly debated and may have been a massive earthquake, which dried up the Ghaggar River. Skeletons discovered in the ruins of Moan Jo Daro ("mount of dead") were thought to indicate that the city was suddenly attacked and the population was wiped out,[21] but further examinations showed that the marks on the skeletons were due to erosion and not of violence.[22]

| Part of a series on |

| Sindhis |

|---|

|

| Kingdoms |

Early history

The ancient city of Roruka, identified with modern Aror/Rohri, was capital of the Sauvira Kingdom, and finds mentioned early Buddhist literature as a major trading center.[23] Sindh finds mention in the Hindu epic Mahabharata as being part of Bharatvarsha. Sindh was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BC. In the late 4th century BC, Sindh was conquered by a mixed army led by Macedonian Greeks under Alexander the Great. The region remained under control of Greek satraps for only a few decades. After Alexander's death, there was a brief period of Seleucid rule, before Sindh was traded to the Mauryan Empire led by Chandragupta in 305 BC. During the rule of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, the Buddhist religion spread to Sindh.

Mauryan rule ended in 185 BC with the overthrow of the last king by the Shunga Dynasty. In the disorder that followed, Greek rule returned when Demetrius I of Bactria led a Greco-Bactrian invasion of India and annexed most of the northwestern lands, including Sindh. Demetrius was later defeated and killed by a usurper, but his descendants continued to rule Sindh and other lands as the Indo-Greek Kingdom. Under the reign of Menander I, many Indo-Greeks followed his example and converted to Buddhism.

In the late 2nd century BC, Scythian tribes shattered the Greco-Bactrian empire and invaded the Indo-Greek lands. Unable to take the Punjab region, they invaded South Asia through Sindh, where they became known as Indo-Scythians (later Western Satraps). By the 1st century AD, the Kushan Empire annexed Sindh. Kushans under Kanishka were great patrons of Buddhism and sponsored many building projects for local beliefs.[24] Ahirs were also found in large numbers in Sindh.[25] Abiria country of Abhira tribe was in southern Sindh.[26][27]

The Kushan Empire was defeated in the mid 3rd century AD by the Sassanid Empire of Persia, who installed vassals known as the Kushanshahs in these far eastern territories. These rulers were defeated by the Kidarites in the late 4th century.

It then came under the Gupta Empire after dealing with the Kidarites. By the late 5th century, attacks by Hephthalite tribes known as the Indo-Hephthalites or Hunas (Huns) broke through the Gupta Empire's northwestern borders and overran much of northwestern India. Concurrently, Ror dynasty ruled parts of the region for several centuries.

Afterwards, Sindh came under the rule of Emperor Harshavardhan, then the Rai Dynasty around 478. The Rais were overthrown by Chachar of Alor around 632. The Brahman dynasty ruled a vast territory that stretched from Multan in the north to the Rann of Kutch, Alor was their capital.

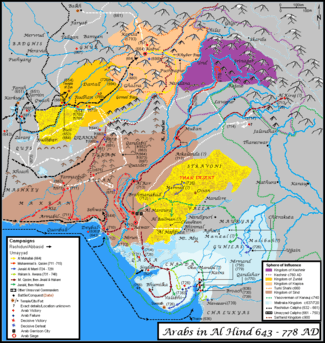

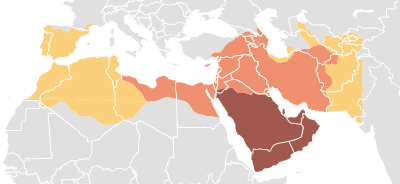

Arrival of Islam

The connection between the Sindh and Islam was established by the initial Muslim missions during the Rashidun Caliphate. Al-Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, who attacked Makran in the year AD 649, was an early partisan of Ali ibn Abu Talib.[28] During the caliphate of Ali, many Jats of Sindh had come under the influence of Shi'ism[29] and some even participated in the Battle of Camel and died fighting for Ali.[28] Under the Umayyads (661 – 750 AD), many Shias sought asylum in the region of Sindh, to live in relative peace in the remote area. Ziyad Hindi is one of those refugees.[30]

Muhammad Ali Jinnah claimed that the Pakistan movement started when the first Muslim put his foot on the soil of Sindh, the Gateway of Islam in India.[31]

In 712, Muhammad bin Qasim conquered the Sindh and Indus Valley, bringing South Asian societies into contact with Islam. Dahir was an unpopular Hindu king that ruled over a Buddhist majority and that Chach of Alor and his kin were regarded as usurpers of the earlier Buddhist Rai Dynasty,[32][33] a view questioned by those who note the diffuse and blurred nature of Hindu and Buddhist practices in the region,[34] especially that of the royalty to be patrons of both and those who believe that Chach may have been a Buddhist.[35][36] The forces of Muhammad bin Qasim defeated Raja Dahir in alliance with the Hindu Jats and other regional governors.

In 711 AD, Muhammad bin Qasim led an Umayyad force of 20,000 cavalry and 5 catapults. Muhammad bin Qasim defeated the Raja Dahir and captured the cities of Alor, Multan and Debal. Sindh became the easternmost State of the Umayyad Caliphate and was referred to as "Sind" on Arab maps, with lands further east known as "Hind". Muhammad bin Qasim built the city of Mansura as his capital; the city then produced famous historical figures such as Abu Mashar Sindhi, Abu Ata al-Sindhi,[37] Abu Raja Sindhi and Sind ibn Ali. At the port city of Debal, most of the Bawarij embraced Islam and became known as Sindhi Sailors, who were renowned for their navigation, geography and languages. After Bin Qasim left, the Umayyads ruled Sindh through the Habbari dynasty.

By the year 750, Debal (modern Karachi) was second only to Basra; Sindhi sailors from the port city of Debal voyaged to Basra, Bushehr, Musqat, Aden, Kilwa, Zanzibar, Sofala, Malabar, Sri Lanka and Java (where Sindhi merchants were known as the Santri). During the power struggle between the Umayyads and the Abbasids. The Habbari Dynasty became semi independent and was eliminated and Mansura was invaded by Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi. Sindh then became an easternmost State of the Abbasid Caliphate ruled by the Soomro Dynasty until the Siege of Baghdad (1258). Mansura was the first capital of the Soomra Dynasty and the last of the Habbari dynasty. Muslim geographers, historians and travelers such as al-Masudi, Ibn Hawqal, Istakhri, Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi, al-Tabari, Baladhuri, Nizami,[38] al-Biruni, Saadi Shirazi, Ibn Battutah and Katip Çelebi[39] wrote about or visited the region, sometimes using the name "Sindh" for the entire area from the Arabian Sea to the Hindu Kush.

Soomra dynasty period

When Sindh was under the Arab Umayyad Caliphate, the Arab Habbari dynasty was in control. The Umayyads appointed Aziz al Habbari as the governor of Sindh. Habbaris ruled Sindh until Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi defeated the Habbaris in 1024. Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi viewed the Abbasid Caliphate to be the caliphs thus he removed the remaining influence of the Umayyad Caliphate in the region and Sindh fell to Abbasid control following the defeat of the Habbaris. The Abbasid Caliphate then appointed Al Khafif from Samarra; 'Soomro' means 'of Samarra' in Sindhi. The new governor of Sindh was to create a better, stronger and stable government. Once he became the governor, he allotted several key positions to his family and friends; thus Al-Khafif or Sardar Khafif Soomro formed the Soomro Dynasty in Sindh;[40] and became its first ruler. Until the Siege of Baghdad (1258) the Soomro dynasty was the Abbasid Caliphate's functionary in Sindh, but after that it became independent.

When the Soomro dynasty lost ties with the Abbasid Caliphate after the Siege of Baghdad (1258,) the Soomra ruler Dodo-I established their rule from the shores of the Arabian Sea to the Punjab in the north and in the east to Rajasthan and in the west to Pakistani Balochistan. The Soomros were one of the first indigenous Muslim dynasties in Sindh of Parmar Rajput origin.[41] They were the first Muslims to translate the Quran into the Sindhi language. The Soomros created a chivalrous culture in Sindh, which eventually facilitated their rule centred at Mansura. It was later abandoned due to changes in the course of the Puran River; they ruled for the next 95 years until 1351. During this period, Kutch was ruled by the Samma Dynasty, who enjoyed good relations with the Soomras in Sindh. Since the Soomro Dynasty lost its support from the Abbasid Caliphate, the Sultans of Delhi wanted a piece of Sindh. The Soomros successfully defended their kingdom for about 36 years, but their dynasties soon fell to the might of the Sultanate of Delhi's massive armies such as the Tughluks and the Khaljis.

Samma Dynasty period

In 1339 Jam Unar founded a Sindhi Muslim Rajput Samma Dynasty and challenged the Sultans of Delhi. He used the title of the Sultan of Sindh. The Samma tribe reached its peak during the reign of Jam Nizamuddin II (also known by the nickname Jám Nindó). During his reign from 1461 to 1509, Nindó greatly expanded the new capital of Thatta and its Makli hills, which replaced Debal. He patronized Sindhi art, architecture and culture. The Samma had left behind a popular legacy especially in architecture, music and art. Important court figures included the poet Kazi Kadal, Sardar Darya Khan, Moltus Khan, Makhdoom Bilawal and the theologian Kazi Kaadan. However, Thatta was a port city; unlike garrison towns, it could not mobilize large armies against the Arghun and Tarkhan Mongol invaders, who killed many regional Sindhi Mirs and Amirs loyal to the Samma. Some parts of Sindh still remained under the Sultans of Delhi and the ruthless Arghuns and the Tarkhans sacked Thatta during the rule of Jam Ferozudin.

Migration of Baloch

According to Dr. Akhtar Baloch, Professor at University of Karachi, and Nadeem Wagan, General Manager at HANDS, the Balochi migrated from Balochistan during the Little Ice Age and settled in Sindh and Punjab. The Little Ice Age is conventionally defined as a period extending from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries,[42][43][44] or alternatively, from about 1300[45] to about 1850.[46][47][48] According to Professor Baloch, the climate of Balochistan was very cold during this epoch and the region was uninhabitable during the winters so the Baloch people emigrated in waves to Sindh[49] and Punjab.

Mughal era

In the year 1524, the few remaining Sindhi Amirs welcomed the Mughal Empire and Babur dispatched his forces to rally the Arghuns and the Tarkhans, branches of a Turkic dynasty. In the coming centuries, Sindh became a region loyal to the Mughals, a network of forts manned by cavalry and musketeers further extended Mughal power in Sindh.[50][51] In 1540 a mutiny by Sher Shah Suri forced the Mughal Emperor Humayun to withdraw to Sindh, where he joined the Sindhi Emir Hussein Umrani. In 1541 Humayun married Hamida Banu Begum, who gave birth to the infant Akbar at Umarkot in the year 1542.[50][52]

During the reign of Akbar the Great, Sindh produced scholars and others such as Mir Ahmed Nasrallah Thattvi, Tahir Muhammad Thattvi and Mir Ali Sir Thattvi and the Mughal chronicler Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak and his brother the poet Faizi was a descendant of a Sindhi Shaikh family from Rel, Siwistan in Sindh. Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak was the author of Akbarnama (an official biographical account of Akbar) and the Ain-i-Akbari (a detailed document recording the administration of the Mughal Empire).

Shah Jahan carved a subah (imperial province), covering Sindh, called Thatta after its capital, out of Multan, further bordering on the Ajmer and Gujarat subahs as well as the rival Persian Safavid empire.

During the Mughal period, Sindhi literature began to flourish and historical figures such as Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Sulatn-al-Aoliya Muhammad Zaman and Sachal Sarmast became prominent throughout the land. In 1603 Shah Jahan visited the State of Sindh; at Thatta, he was generously welcomed by the locals after the death of his father Jahangir. Shah Jahan ordered the construction of the Shahjahan Mosque, which was completed during the early years of his rule under the supervision of Mirza Ghazi Beg. During his reign, in 1659 in the Mughal Empire, Muhammad Salih Tahtawi of Thatta created a seamless celestial globe with Arabic and Persian inscriptions using a wax casting method.[53][54]

Sindh was home to several wealthy merchant-rulers such as Mir Bejar of Sindh, whose great wealth had attracted the close ties with the Sultan bin Ahmad of Oman.[55]

In the year 1701, the Kalhora Nawabs were authorized in a firman by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb to administer subah Sindh.

From 1752 to 1762, Marathas collected Chauth or tributes from Sindh.[56] Maratha power was decimated in the entire region after the Third Battle of Panipat in 1761. In 1762, Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro brought stability in Sindh, he reorganized and independently defeated the Marathas and their prominent vassal the Rao of Kuch in the Thar Desert and returned victoriously.

After the Sikhs annexed Multan, the Kalhora Dynasty supported counterattacks against the Sikhs and defined their borders.[57]

In 1783 a firman which designated Mir Fateh Ali Khan Talpur as the new Nawab of Sindh, and mediated peace particularly after the Battle of Halani and the defeat of the ruling Kalhora by the Talpur Baloch tribes.[58]

Caravan of merchants in the Indus River Valley

Caravan of merchants in the Indus River Valley

Talpurs

The Talpur dynasty was established by members of the Talpur tribe. The Talpur tribes migrated from Dera Ghazi Khan in Punjab to Sindh on the invitation of Kalhora to help them organize unruly Baloch tribes living in Sindh. Talpurs, who learned the Sindhi language, settled in northern Sindh. Very soon they united all the Baloch tribes of Sindh and formed a confederacy against the Kalhora Dynasty.

Four branches of the dynasty were established following the defeat of the Kalhora dynasty at the Battle of Halani in 1743:[59] one ruled lower Sindh from the city of Hyderabad, another ruled over upper Sindh from the city of Khairpur, a third ruled around the eastern city of Mirpur Khas, and a fourth was based in Tando Muhammad Khan. The Talpurs were ethnically Baloch,[60] and Shia by faith.[61] They ruled from 1783, until 1843, when they were in turn defeated by the British at the Battle of Miani and Battle of Dubbo.[62] The northern Khairpur branch of the Talpur dynasty, however, continued to maintain a degree of sovereignty during British rule as the princely state of Khairpur,[60] whose ruler elected to join the new Dominion of Pakistan in October 1947 as an autonomous region, before being fully amalgamated in the West Pakistan in 1955.

British Raj

In 1802, when Mir Ghulam Ali Khan Talpur succeeded as the Talpur Nawab, internal tensions broke out in the state. As a result, the following year the Maratha Empire declared war on Sindh and Berar Subah, during which Arthur Wellesley took a leading role causing much early suspicion between the Emirs of Sindh and the British Empire.[63] The British East India Company made its first contacts in the Sindhi port city of Thatta, which according to a report was:

"a city as large as London containing 50,000 houses which were made of stone and mortar with large verandahs some three or four stories high ... the city has 3,000 looms ... the textiles of Sindh were the flower of the whole produce of the East, the international commerce of Sindh gave it a place among that of Nations, Thatta has 400 schools and 4,000 Dhows at its docks, the city is guarded by well armed Sepoys".

British and Bengal Presidency forces under General Charles James Napier arrived in Sindh in the mid-19th century and conquered Sindh in February 1843.[64] The Baloch coalition led by Talpur under Mir Nasir Khan Talpur was defeated at the Battle of Miani during which 5,000 Talpur Baloch were killed. Shortly afterwards, Hoshu Sheedi commanded another army at the Battle of Dubbo, where 5,000 Baloch were killed.

The first Agha Khan (was escaping persecution from Persia and looking for a foothold in the British Raj) he helped the British in their conquest of Sindh. As a result, he was granted a lifetime pension.

A British journal[65] by Thomas Postans mentions the captive Sindhi Amirs: "The Amirs as being the prisoners of 'Her Majesty'... they are maintained in strict seclusion; they are described as Broken-Hearted and Miserable men, maintaining much of the dignity of fallen greatness, and without any querulous or angry complaining at this unlivable source of sorrow, refusing to be comforted". Within weeks, Charles Napier and his forces occupied Sindh.

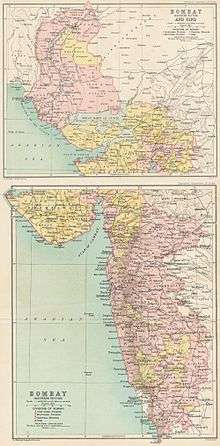

After 1853 the British divided Sindh into districts and later made it part of British India's Bombay Presidency.

In the year 1868, the Bombay Presidency assigned Narayan Jagannath Vaidya to replace the Abjad used in Sindhi, with the Khudabadi script. The script was decreed a standard script by the Bombay Presidency thus inciting anarchy in the Muslim majority region. A powerful unrest followed, after which Twelve Martial Laws were imposed by the British authorities.[66]

The Bombay Presidency caused the rise of rebels such as Sibghatullah Shah Rashidi pioneered the Sindhi Muslim Hur Movement against the British Raj. He was hanged on 20 March 1943 in Hyderabad, Sindh. His burial place is not known.

During the British period, railways, printing presses and bridges were introduced in the province. Writers like Mirza Kalich Beg compiled and traced the literary history of Sindh.

Although Sindh had a culture of religious syncretism, communal harmony and tolerance due to Sindh's strong Sufi culture in which both Sindhi Muslims and Sindhi Hindus partook,[67] the mostly Muslim peasantry was oppressed by the Hindu moneylending class and also by the landed Muslim elite.[68] Sindhi Muslims eventually demanded the separation of Sindh from the Bombay Presidency, a move opposed by Sindhi Hindus.[69][70][71]

By 1936 Sindh was separated from the Bombay Presidency. Elections in 1937 resulted in local Sindhi Muslim parties winning the bulk of seats. By the mid-1940s the Muslim League gained a foothold in the province and after winning over the support of local Sufi pirs,[72] it didn't take long for the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims to campaign for the creation of Pakistan.[73][74]

Population

Demographics

| Demographic Indicators | |

|---|---|

| Urban population | 52.02% |

| Rural population | 47.98% |

| Population growth rate | 2.41% |

| Gender ratio (male per 100 female) | 108.58 |

| Economically active population | 22.75% (Old Data) |

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | Urban |

| 1951 | 6,047,748 | 29.23% |

| 1961 | 8,367,065 | 37.85% |

| 1972 | 14,155,909 | 40.44% |

| 1981 | 19,028,666 | 43.31% |

| 1998 | 29,991,161 | 48.75% |

| 2017 | 47,886,051 | 52.02% |

Sindh has the 2nd highest Human Development Index out of all of Pakistan's provinces at 0.628.[75] The 2017 Census of Pakistan indicated a population of 47.9 million.

The major ethnic group of the province is the Sindhis, but there is also a significant presence of other groups. Sindhis of Baloch origin make up about 30% of the total Sindhi population (although they speak Sindhi Saraiki as their native tongue), while Urdu-speaking Muhajirs make up over 19% of the total population of the province, while Punjabi are 10% and Pashtuns represent 7%. In August 1947, before the partition of India, the total population of Sindh was 3,887,070 out of which 2,832,000 were Muslims and 1,015,000 were Hindus[76]

Religion

Islam in Sindh has a strong Sufi ethos with numerous Muslim saints and mystics, such as the Sufi poet Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, having lived in Sindh historically. One popular legend which highlights the strong Sufi presence in Sindh is that 125,000 Sufi saints and mystics are buried on Makli Hill near Thatta.[78] The development of Sufism in Sindh was similar to the development of Sufism in other parts of the Muslim world. In the 16th century two Sufi tareeqat (orders) – Qadria and Naqshbandia – were introduced in Sindh.[79] Sufism continues to play an important role in the daily lives of Sindhis.[80]

Sindh also has Pakistan's highest percentage of Hindu residents, with 8.9% of Sindh's population overall, and 13.56% of Sindh's rural population, classifying itself as Hindu,[77] and a majority of residents in Tharparkar District identifying themselves as Hindu.[81][10] The communal harmony between Sindhi Muslims and Hindus is an example of Sindh's pluralistic and tolerant Sufi culture.[82]

There are approximately 10,000 Sikhs in Sindh.[83]

Languages

According to the 2017 census, the most widely spoken language in the province is Sindhi, the first language of 62% of the population. It is followed by Urdu (18%), Pashto (5.5%), Punjabi (5.3%), Saraiki (2.2%) and Balochi (2%).[84]

Other languages with substantial numbers of speakers include Kutchi and Gujarati.[85] Other minority languages include Aer, Bagri, Bhaya, Brahui, Dhatki, Ghera, Goaria, Gurgula, Jadgali, Jandavra, Jogi, Kabutra, Kachi Koli, Parkari Koli, Wadiyari Koli, Loarki, Marwari, Sansi, and Vaghri.[86]

According to the 1998 census, 7.3% of people Karachi's residents are Sindhi-speaking. However, since the last few decades, every year thousands of Sindhi speaking from the rural areas are moving and settling to the Karachi due to which population of the Sindhis is increasing drastically.[87] Karachi is 40% populated by Muhajirs who speak Urdu.[88] Other immigrant communities in Karachi are Pashtuns from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjabis from Punjab and other linguistic groups from various regions of Pakistan.

Geography and nature

Sindh is in the western corner of South Asia, bordering the Iranian plateau in the west. Geographically it is the third largest province of Pakistan, stretching about 579 kilometres (360 mi) from north to south and 442 kilometres (275 mi) (extreme) or 281 kilometres (175 mi) (average) from east to west, with an area of 140,915 square kilometres (54,408 sq mi) of Pakistani territory. Sindh is bounded by the Thar Desert to the east, the Kirthar Mountains to the west and the Arabian Sea in the south. In the centre is a fertile plain along the Indus River.

Flora

The province is mostly arid with scant vegetation except for the irrigated Indus Valley. The dwarf palm, Acacia Rupestris (kher), and Tecomella undulata (lohirro) trees are typical of the western hill region. In the Indus valley, the Acacia nilotica (babul) (babbur) is the most dominant and occurs in thick forests along the Indus banks. The Azadirachta indica (neem) (nim), Zizyphys vulgaris (bir) (ber), Tamarix orientalis (jujuba lai) and Capparis aphylla (kirir) are among the more common trees.

Mango, date palms and the more recently introduced banana, guava, orange and chiku are the typical fruit-bearing trees. The coastal strip and the creeks abound in semi-aquatic and aquatic plants and the inshore Indus delta islands have forests of Avicennia tomentosa (timmer) and Ceriops candolleana (chaunir) trees. Water lilies grow in abundance in the numerous lake and ponds, particularly in the lower Sindh region.

Fauna

Among the wild animals, the Sindh ibex (sareh), blackbuck, wild sheep (Urial or gadh) and wild bear are found in the western rocky range. The leopard is now rare and the Asiatic cheetah extinct. The Pirrang (large tiger cat or fishing cat) of the eastern desert region is also disappearing. Deer occur in the lower rocky plains and in the eastern region, as do the striped hyena (charakh), jackal, fox, porcupine, common gray mongoose and hedgehog. The Sindhi phekari, red lynx or Caracal cat, is found in some areas. Phartho (hog deer) and wild bear occur, particularly in the central inundation belt. There are bats, lizards and reptiles, including the cobra, lundi (viper) and the mysterious Sindh krait of the Thar region, which is supposed to suck the victim's breath in his sleep. Some unusual sightings of Asian cheetah occurred in 2003 near the Balochistan border in Kirthar Mountains. The rare houbara bustard find Sindh's warm climate suitable to rest and mate. Unfortunately, it is hunted by locals and foreigners.

Crocodiles are rare and inhabit only the backwaters of the Indus, eastern Nara channel and Karachi backwater. Besides a large variety of marine fish, the plumbeous dolphin, the beaked dolphin, rorqual or blue whale and skates frequent the seas along the Sindh coast. The Pallo (Sable fish), a marine fish, ascends the Indus annually from February to April to spawn. The Indus river dolphin is among the most endangered species in Pakistan and is found in the part of the Indus river in northern Sindh. Hog deer and wild bear occur, particularly in the central inundation belt.

Although Sindh has a semi arid climate, through its coastal and riverine forests, its huge fresh water lakes and mountains and deserts, Sindh supports a large amount of varied wildlife. Due to the semi-arid climate of Sindh the left out forests support an average population of jackals and snakes. The national parks established by the Government of Pakistan in collaboration with many organizations such as World Wide Fund for Nature and Sindh Wildlife Department support a huge variety of animals and birds. The Kirthar National Park in the Kirthar range spreads over more than 3000 km2 of desert, stunted tree forests and a lake. The KNP supports Sindh ibex, wild sheep (urial) and black bear along with the rare leopard. There are also occasional sightings of The Sindhi phekari, ped lynx or Caracal cat. There is a project to introduce tigers and Asian elephants too in KNP near the huge Hub Dam Lake. Between July and November when the monsoon winds blow onshore from the ocean, giant olive ridley turtles lay their eggs along the seaward side. The turtles are protected species. After the mothers lay and leave them buried under the sands the SWD and WWF officials take the eggs and protect them until they are hatched to keep them from predators.

Climate

Sindh lies in a tropical to subtropical region; it is hot in the summer and mild to warm in winter. Temperatures frequently rise above 46 °C (115 °F) between May and August, and the minimum average temperature of 2 °C (36 °F) occurs during December and January in the northern and higher elevated regions. The annual rainfall averages about seven inches, falling mainly during July and August. The southwest monsoon wind begins in mid-February and continues until the end of September, whereas the cool northerly wind blows during the winter months from October to January.

Sindh lies between the two monsoons—the southwest monsoon from the Indian Ocean and the northeast or retreating monsoon, deflected towards it by the Himalayan mountains—and escapes the influence of both. The region's scarcity of rainfall is compensated by the inundation of the Indus twice a year, caused by the spring and summer melting of Himalayan snow and by rainfall in the monsoon season.

Sindh is divided into three climatic regions: Siro (the upper region, centred on Jacobabad), Wicholo (the middle region, centred on Hyderabad), and Lar (the lower region, centred on Karachi). The thermal equator passes through upper Sindh, where the air is generally very dry. Central Sindh's temperatures are generally lower than those of upper Sindh but higher than those of lower Sindh. Dry hot days and cool nights are typical during the summer. Central Sindh's maximum temperature typically reaches 43–44 °C (109–111 °F). Lower Sindh has a damper and humid maritime climate affected by the southwestern winds in summer and northeastern winds in winter, with lower rainfall than Central Sindh. Lower Sindh's maximum temperature reaches about 35–38 °C (95–100 °F). In the Kirthar range at 1,800 m (5,900 ft) and higher at Gorakh Hill and other peaks in Dadu District, temperatures near freezing have been recorded and brief snowfall is received in the winters.

Major cities

| List of major cities in Sindh | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | District(s) | Population | Image |

| 1 | Karachi | Karachi East Karachi West Karachi South Karachi Central Malir Korangi | 14,910,352 |  |

| 2 | Hyderabad | Hyderabad | 1,732,693 |  |

| 3 | Sukkur | Sukkur | 499,900 |  |

| 4 | Larkana | Larkana | 490,508 |  |

| 5 | Nawabshah | Shaheed Benazirabad | 279,688 | |

| 6 | Kotri | Jamshoro | 259,358 |  |

| 7 | Mirpur Khas | Mirpur Khas | 233,916 | |

| Source: Pakistan Census 2017[90] | ||||

| This is a list of city proper populations and does not indicate metro populations. | ||||

Government

Sindh province

| Provincial animal | Sindh ibex |  |

|---|---|---|

| Provincial bird | Black partridge |  |

| Provincial flower | Nerium (common) |  |

| Provincial tree | Neem Tree |  |

The Provincial Assembly of Sindh is a unicameral and consists of 168 seats, of which 5% are reserved for non-Muslims and 17% for women. The provincial capital of Sindh is Karachi. The provincial government is led by Chief Minister who is directly elected by the popular and landslide votes; the Governor serves as a ceremonial representative nominated and appointed by the President of Pakistan. The administrative boss of the province who is in charge of the bureaucracy is the Chief Secretary Sindh, who is appointed by the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Most of the influential Sindhi tribes in the province are involved in Pakistan's politics.

In addition, Sindh's politics leans towards the left-wing and its political culture serves as a dominant place for the left-wing spectrum in the country.[94] The province's trend towards the Pakistan Peoples Party and away from the Pakistan Muslim League (N) can be seen in nationwide general elections, in which, Sindh is a stronghold of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).[94] The PML(N) has a limited support due to its centre-right agenda.[95]

In metropolitan cities such as Karachi and Hyderabad, the MQM (another left-wing party with the support of Muhajirs) has a considerable vote bank and support.[94] Minor leftist parties such as People's Movement also found support in rural areas of the province.[96]

Divisions

In 2008, after the public elections, the new government decided to restore the structure of Divisions of all provinces.[97] In Sindh after the lapse of the Local Governments Bodies term in 2010 the Divisional Commissioners system was to be restored.[98][99] [100]

In July 2011, following excessive violence in the city of Karachi and after the political split between the ruling PPP and the majority party in Sindh, the MQM and after the resignation of the MQM Governor of Sindh, PPP and the Government of Sindh decided to restore the commissionerate system in the province. As a consequence, the five divisions of Sindh were restored – namely Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Mirpurkhas and Larkana with their respective districts. Subsequently, two new divisions have been added in Sindh, Banbore and Nawab Shah/Shaheed Benazirabad division.[101]

Karachi district has been de-merged into its five original constituent districts: Karachi East, Karachi West, Karachi Central, Karachi South and Malir. Recently Korangi has been upgraded to the status of the sixth district of Karachi. These six districts form the Karachi Division now.[102]

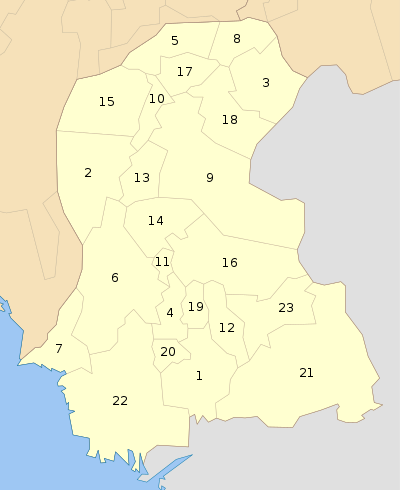

Districts

| Map | Sr. No. | District | Headquarters | Area (km²) | Population (in 2017) |

Density (people/km²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 | Badin | Badin | 6,470 | 1,804,516 | 279 |

| 2 | Dadu | Dadu | 8,034 | 1,550,266 | 193 | |

| 3 | Ghotki | Ghotki | 6,506 | 1,647,239 | 253 | |

| 4 | Hyderabad | Hyderabad | 1,022 | 2,201,079 | 2,155 | |

| 5 | Jacobabad | Jacobabad | 2,771 | 1,006,297 | 363 | |

| 6 | Jamshoro | Jamshoro | 11,250 | 993,142 | 88 | |

| 7 | Karachi Central | Karachi | 62 | 2,972,639 | 48,336 | |

| 8 | Kashmore (formerly Kandhkot) | Kashmore | 2,551 | 1,089,169 | 427 | |

| 9 | Khairpur | Khairpur | 15,925 | 2,405,523 | 151 | |

| 10 | Larkana | Larkana | 1,906 | 1,524,391 | 800 | |

| 11 | Matiari | Matiari | 1,459 | 769,349 | 527 | |

| 12 | Mirpur Khas | Mirpur Khas | 3,319 | 1,505,876 | 454 | |

| 13 | Naushahro Feroze | Naushahro Feroze | 2,027 | 1,612,373 | 369 | |

| 14 | Shaheed Benazirabad (formerly Nawabshah) | Nawabshah | 4,618 | 1,612,847 | 349 | |

| 15 | Qambar Shahdadkot | Qambar | 5,599 | 1,341,042 | 240 | |

| 16 | Sanghar | Sanghar | 10,259 | 2,057,057 | 200 | |

| 17 | Shikarpur | Shikarpur | 2,577 | 1,231,481 | 478 | |

| 18 | Sukkur | Sukkur | 5,216 | 1,487,903 | 285 | |

| 19 | Tando Allahyar | Tando Allahyar | 1,573 | 836,887 | 532 | |

| 20 | Tando Muhammad Khan | Tando Muhammad Khan | 1,814 | 677,228 | 373 | |

| 21 | Tharparkar | Mithi | 19,808 | 1,649,661 | 83 | |

| 22 | Thatta | Thatta | 7,705 | 979,817 | 127 | |

| 23 | Umerkot | Umerkot | 5,503 | 1,073,146 | 195 | |

| 24 (22) | Sujawal | Sujawal | 8,699 | 781,967 | 90 | |

| 25 (7) | Karachi East | Karachi | 165 | 2,909,921 | 17,625 | |

| 26 (7) | Karachi South | Karachi | 85 | 1,791,751 | 21,079 | |

| 27 (7) | Karachi West | Karachi | 630 | 3,914,757 | 6,212 | |

| 28 (7) | Korangi | Korangi Town | 95 | 2,457,019 | 25,918 | |

| 29 (7) | Malir | Malir Town | 2,635 | 2,008,901 | 762 |

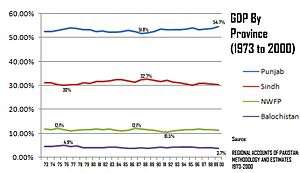

Economy

Sindh has the second largest economy in Pakistan. A 2016 study commissioned by Pakistan Ministry of Planning found that urban Sindh and northern Punjab province are the most prosperous regions in Pakistan.[103] Its GDP per capita was $1,400 in 2010 which is 50 percent more than the rest of the nation or 35 percent more than the national average. Historically, Sindh's contribution to Pakistan's GDP has been between 30% to 32.7%. Its share in the service sector has ranged from 21% to 27.8% and in the agriculture sector from 21.4% to 27.7%. Performance wise, its best sector is the manufacturing sector, where its share has ranged from 36.7% to 46.5%.

Endowed with coastal access, Sindh is a major centre of economic activity in Pakistan and has a highly diversified economy ranging from heavy industry and finance centred in Karachi to a substantial agricultural base along the Indus. Manufacturing includes machine products, cement, plastics, and other goods.

Agriculture is very important in Sindh with cotton, rice, wheat, sugar cane, dates, bananas, and mangoes as the most important crops. The largest and finer quality of rice is produced in Larkano district.[104][105]

Education

| Year | Literacy rate |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 60.77 |

| 1981 | 37.5% |

| 1998 | 45.29% |

| 2008 | 60.7% |

| 2012 | 69.50% |

The following is a chart of the education market of Sindh estimated by the government in 1998:[106]

| Qualification | Urban | Rural | Total | Enrollment ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 14,839,862 | 15,600,031 | 30,439,893 | — |

| Below Primary | 1,984,089 | 3,332,166 | 5,316,255 | 100.00 |

| Primary | 3,503,691 | 5,687,771 | 9,191,462 | 82.53 |

| Middle | 3,073,335 | 2,369,644 | 5,442,979 | 52.33 |

| Matriculation | 2,847,769 | 2,227,684 | 5,075,453 | 34.45 |

| Intermediate | 1,473,598 | 1,018,682 | 2,492,280 | 17.78 |

| Diploma, Certificate... | 1,320,747 | 552,241 | 1,872,988 | 9.59 |

| BA, BSc... degrees | 440,743 | 280,800 | 721,543 | 9.07 |

| MA, MSc... degrees | 106,847 | 53,040 | 159,887 | 2.91 |

| Other qualifications | 89,043 | 78,003 | 167,046 | 0.54 |

Major public and private educational institutes in Sindh include:

- Adamjee Government Science College

- Aga Khan University

- APIIT

- Applied Economics Research Centre

- Bahria University

- Baqai Medical University

- Chandka Medical College Larkana

- Cadet College Petaro

- College of Digital Sciences

- College of Physicians & Surgeons Pakistan

- COMMECS Institute of Business and Emerging Sciences

- D. J. Science College

- Dawood College of Engineering and Technology

- Defence Authority Degree College for Men

- Dow International Medical College

- Dow University of Health Sciences

- Fatima Jinnah Dental College

- Federal Urdu University

- GBELS Dourai Mahar Taluka Daur Distt: Shaheed Benazirabad

- Ghulam Muhammad Mahar Medical College Sukkur

- Government College for Men Nazimabad

- Government College Hyderabad

- Government College of Commerce & Economics

- Government College of Technology, Karachi

- Government Degree College Matiari

- Government High School Ranipur

- Government Islamia Science College Sukkur

- Government Muslim Science College Hyderabad

- Government National College (Karachi)

- Greenwich University (Karachi)

- Hamdard University

- Hussain Ebrahim Jamal Research Institute of Chemistry

- Imperial Science College Nawabshah

- Indus Valley Institute of Art and Architecture

- Institute of Business Administration, Karachi

- Institute of Business Administration, Sukkar

- Institute of Business Management

- Institute of Industrial Electronics Engineering

- Institute of Sindhology

- Iqra University

- Islamia Science College (Karachi)

- Isra University Hyderabad

- Jinnah Medical & Dental College

- Jinnah Polytechnic Institute

- Jinnah Post Graduate Medical Centre

- Jinnah University for Women

- KANUPP Institute of Nuclear Power Engineering

- Karachi School of Business and Leadership

- Liaquat University of Medical & Health Sciences

- Mehran University of Engineering and Technology

- Mohammad Ali Jinnah University

- National Academy of Performing Arts

- National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences

- National University of Modern Languages

- National University of Sciences and Technology

- NED University of Engineering and Technology

- Ojha Institute of Chest Diseases

- PAF Institute of Aviation Technology

- TES Public School, Daur

- PAF KIET- Karachi Institute of Economics and Technology

- Pakistan Navy Engineering College

- Pakistan Shipowners' College

- Pakistan Steel Cadet College

- Peoples Medical College for Girls Nawabshah

- PIA Training Centre Karachi

- Provincial Institute of Teachers Education Nawabshah

- Public School Hyderabad

- Quaid-e-Awam University of Engineering, Science and Technology, Nawabshah

- Rana Liaquat Ali Khan Government College of Home Economics

- Saint Patrick's College, Karachi

- Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai University

- Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Medical College

- Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology

- Sindh Agriculture University

- Sindh Medical College

- Superior College of Science Hyderabad

- Sindh Muslim Law College

- Sir Syed Government Girls College

- Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology

- St. Joseph's College

- Sukkur Institute of Science & Technology

- Textile Institute of Pakistan

- University of Karachi

- University of Sindh

- Usman Institute of Technology

- Ziauddin Medical University

Culture

.jpg)

The rich culture, art and architectural landscape of Sindh have fascinated historians. The culture, folktales, art and music of Sindh form a mosaic of human history.[107]

Cultural heritage

Sindh has a rich heritage of traditional handicraft that has evolved over the centuries. Perhaps the most professed exposition of Sindhi culture is in the handicrafts of Hala, a town some 30 kilometres from Hyderabad. Hala's artisans manufacture high-quality and impressively priced wooden handicrafts, textiles, paintings, handmade paper products, and blue pottery. Lacquered wood works known as Jandi, painting on wood, tiles, and pottery known as Kashi, hand weaved textiles including khadi, susi, and ajraks are synonymous with Sindhi culture preserved in Hala's handicraft.

The work of Sindhi artisans was sold in ancient markets of Damascus, Baghdad, Basra, Istanbul, Cairo and Samarkand. Referring to the lacquer work on wood locally known as Jandi, T. Posten (an English traveller who visited Sindh in the early 19th century) asserted that the articles of Hala could be compared with exquisite specimens of China. Technological improvements such as the spinning wheel (charkha) and treadle (pai-chah) in the weaver's loom were gradually introduced and the processes of designing, dyeing and printing by block were refined. The refined, lightweight, colourful, washable fabrics from Hala became a luxury for people used to the woollens and linens of the age.[108]

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as the World Wildlife Fund, Pakistan, play an important role to promote the culture of Sindh. They provide training to women artisans in the interior of Sindh so they get a source of income. They promote their products under the name of "Crafts Forever". Many women in rural Sindh are skilled in the production of caps. Sindhi caps are manufactured commercially on a small scale at New Saeedabad and Hala New. These are in demand with visitors from Karachi and other places; however, these manufacturing units have a limited production capacity. Sindhi people began celebrating Sindhi Topi Day on 6 December 2009, to preserve the historical culture of Sindh by wearing Ajrak and Sindhi topi.[109]

Tourism

Tourist sites include the ruins of Mohenjo-daro near the city of Larkana, Runi Kot, Kot Deji, the Jain temples of Nangar Parker and the historic temple of Sadhu Bela, Sukkur. Islamic architecture is quite prominent in the province; its numerous mausoleums include the ancient Shahbaz Qalander mausoleum.

- Sachal Sarmast (Sufi poet) Daraz near Ranipur

- Aror (ruins of historical city) near Sukkur

- Chaukandi Tombs, Karachi

- Forts at Hyderabad and Umarkot

- Gorakh Hill in Dadu

- Kahu-Jo-Darro near Mirpurkhas

- Kirthar National Park in Dadu

- Kot Diji Fort, Kot Diji

- Kotri Barrage near Hyderabad

- Makli Hill, Asia's largest necropolis, Makli, Thatta

- Minar-e-Mir Masum Shah, Sukkur

- Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi

- Rani Bagh, Hyderabad

- Ranikot Fort near Sann

- Ruins of Mohenjo-daro and Museum near Larkana

- Pakka Qila, Hyderabad

- Sadhu Bela Temple near Sukkur

- Shahjahan Mosque, Thatta

- Shrine of Allama Makhdoom Muhammad Hashim Thattvi, Thatta

- Shrine of Shah Inayat Shaheed, Jhok

- Shrine of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, Bhit Shah

- Shrine of Shahbaz Qalander in Sehwan, Dadu

- Sukkur Barrage, Sukkur

- malhan mata temple haryar, mithi

- Talpurs' Faiz Mahal Palace, Khairpur

Sukkur Bridge

Sukkur Bridge

Faiz Mahal, Khairpur

Faiz Mahal, Khairpur Ranikot Fort, one of the largest forts in the world

Ranikot Fort, one of the largest forts in the world Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro

Excavated ruins of Mohenjo-daro- Karachi Beach

- Qasim fort

Bakri Waro Lake, Khairpur

Bakri Waro Lake, Khairpur

Tomb of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai

Tomb of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai

See also

- Bagh Prints

- Brahma from Mirpur-Khas

- Debal

- Institute of Sindhology

- List of cities in Sindh

- List of cities in Sindh by population

- List of cultural heritage sites in Sindh

- List of medical schools in Sindh

- List of districts of Pakistan

- List of Sindhi people

- Provincial Highways of Sindh

- Sindh cricket team

- Mansura, Sindh

- Mohenjodaro

- Muhajir Sooba

- Sind Division

- Sindhu Kingdom

- Sufism in Sindh

- Sindh (disambiguation)

- Sindhi dress

- Tomb paintings of Sindh

Notes

References

- "DISTRICT WISE CENSUS RESULTS CENSUS 2017" (PDF). www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Welcome to the Website of Provincial Assembly of Sindh". www.pas.gov.pk.

- "LgdSindh - News Blog". LgdSindh.

- "Sindh Province". ActionAid. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- "Sindh Province of Pakistan". Consulate General of Russia. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Staff reporter (9 March 2014). "Sindh must exploit potential for fruit production". The Nation, 2014. The Nation. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Markhand, Ghulam Sarwar; Saud, Adila A. "Dates in Sindh". Proceedings of the International Dates Seminar. SALU Press. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Editorial (3 September 2007). "How to grow Bananas". Dawn News, 2007. Dawn News. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Tharparkar District Official Website – District Profile – Demography Archived March 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Judy Wakabayashi; Rita Kothari (2009). Decentering Translation Studies: India and Beyond. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-90-272-2430-9.

- "Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List (Pakistan)". UNESCO. UNESCO. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Phiroze Vasunia 2013, p. 6.

- Southworth, Franklin. The Reconstruction of Prehistoric South Asian Language Contact (1990) p. 228

- Burrow, T. Dravidian Etymology Dictionary p. 227

- "Sindh, not Sind". The Express Tribune. Web Desk. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- Choudhary Rahmat Ali (28 January 1933). "Now or Never. Are we to live or perish forever?".

- S. M. Ikram (1 January 1995). Indian Muslims and partition of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-81-7156-374-6. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- "Archaeological Ruins at Moanjodaro". The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) website. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Suhail Zaheer Lari, An Illustrated History of Sindh (1994, Karachi) p. 16, 17

- Sohail Zaheer Lari, An Illustrated History of Sindh (1994, Karachi) p. 17

- Edwin Bryant (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. pp. 159–60.

- Derryl N. MacLean (1989), Religion and Society in Arab Sind, p.63

- which began about AD 127. "Falk 2001, pp. 121–136", Falk (2001), pp. 121–136, Falk, Harry (2004), pp. 167–176 and Hill (2009), pp. 29, 33, 368–371.

- John Beames (1970). A comparative grammar of the modern Aryan languages of India: to wit, Hindi, Panjabi, Sindhi, Gujarati, Marathi, Oriya and Bengali. Munshiram Manoharlal. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- Foreign influence on ancient India By Krishna Chandra Sagar

- Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India – Krishna Chandra Sagar – Google Books. ISBN 9788172110284. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- MacLean, Derryl N. (1989), Religion and Society in Arab Sind, pp. 126, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-08551-3

- S. A. A. Rizvi, "A socio-intellectual History of Isna Ashari Shi'is in India", Volo. 1, pp. 138, Mar'ifat Publishing House, Canberra (1986).

- S. A. N. Rezavi, "The Shia Muslims", in History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 2, Part. 2: "Religious Movements and Institutions in Medieval India", Chapter 13, Oxford University Press (2006).

- "Pakistan Movement". cybercity-online.net.

- Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES, presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006 . Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- Naik, C.D. (2010). Buddhism and Dalits: Social Philosophy and Traditions. Delhi: Kalpaz Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-81-7835-792-8.

- P. 151 Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World By André Wink

- P. 164 Notes on the religious, moral, and political state of India before the Mahomedan invasion, chiefly founded on the travels of the Chinese Buddhist priest Fai Han in India, A.D. 399, and on the commentaries of Messrs. Remusat, Klaproth and Burnouf, Lieutenant-Colonel W.H. Sykes by Sykes, Colonel;

- P. 505 The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians by Henry Miers Elliot, John Dowson

- Seidensticker, Tilman (December 2008). "Abū ʿAṭāʾ al-Sindī – Brill Reference". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Referenceworks.brillonline.com. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Bose, Sugata (26 December 2004). A Hundred Horizons: The Indian Ocean in the Age of Global Empire – Sugata Bose – Google Books. ISBN 9780674028579. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Topics". MuslimHeritage.com. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Data" (PDF). www.uok.edu.pk.

- Siddiqui, Habibullah. "The Soomras of Sindh: their origin, main characteristics and rule – an overview (general survey) (1025 – 1351 AD)" (PDF). Literary Conference on Soomra Period in Sindh.

- Mann, Michael (2003). "Little Ice Age" (PDF). In Michael C MacCracken and John S Perry (ed.). Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change, Volume 1, The Earth System: Physical and Chemical Dimensions of Global Environmental Change. John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Lamb, HH (1972). "The cold Little Ice Age climate of about 1550 to 1800". Climate: present, past and future. London: Methuen. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-416-11530-7. (noted in Grove 2004:4).

- "Earth observatory Glossary L-N". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Green Belt MD: NASA. Retrieved 17 July 2015..

- Miller et al. 2012. "Abrupt onset of the Little Ice Age triggered by volcanism and sustained by sea-ice/ocean feedbacks" Geophysical Research Letters 39, 31 January: abstract (formerly on AGU website) (accessed via wayback machine 11 July 2015); see press release on AGU website (accessed 11 July 2015).

- Grove, J.M., Little Ice Ages: Ancient and Modern, Routledge, London (2 volumes) 2004.

- Matthews, J.A. and Briffa, K.R., "The 'Little Ice Age': re-evaluation of an evolving concept", Geogr. Ann., 87, A (1), pp. 17–36 (2005). Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- "1.4.3 Solar Variability and the Total Solar Irradiance – AR4 WGI Chapter 1: Historical Overview of Climate Change Science". Ipcc.ch. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- "From Zardaris to Makranis: How the Baloch came to Sindh – The Express Tribune". 28 March 2014.

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia by Nicholas Tarling p.39. ISBN 9780521663700.

- Cambridge illustrated atlas, warfare: Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792 by Jeremy Black p.16

- "Hispania [Publicaciones periódicas]. Volume 74, Number 3, September 1991 – Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". cervantesvirtual.com. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Savage-Smith, Emilie (1985), Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their History, Construction, and Use, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- Kazi, Najma (24 November 2007). "Seeking Seamless Scientific Wonders: Review of Emilie Savage-Smith's Work". FSTC Limited. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- Bhacker, Mohmed Reda (17 November 1992). Trade and Empire in Muscat and Zanzibar: The Roots of British Domination – M. Reda Bhacker – Google Books. ISBN 9780415079976. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Sen, S. N (2006). History Modern India. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-224-1774-6.

- Sethi, Jasbir Singh. Fall and Colored Leaves – Jasbir Singh Sethi – Google Books. ISBN 9788189540616. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Qammaruddin Bohra, City of Hyderabad Sindh 712–1947 (2000).

- "History of Khairpur and the royal Talpurs of Sindh". Daily Times. 21 April 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Solomon, R. V.; Bond, J. W. (2006). Indian States: A Biographical, Historical, and Administrative Survey. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1965-4.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1980). Islam in the Indian Subcontinent. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-06117-0.

- "The Royal Talpurs of Sindh - Historical Background". www.talpur.org. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley

- General Napier apocryphally reported his conquest of the province to his superiors with the one-word message peccavi, a schoolgirl's pun recorded in Punch (magazine) relying on the Latin word's meaning, "I have sinned", homophonous to "I have Sindh". Eugene Ehrlich, Nil Desperandum: A Dictionary of Latin Tags and Useful Phrases [Original title: Amo, Amas, Amat and More], BCA 1992 [1985], p. 175.

- Postans, Thomas (1843). Personal observations on Sindh: the manners and customs of its inhabitants ... – Thomas Postans – Google Boeken. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "Sindhi alphabets, pronunciation and language". Omniglot.com.

- Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 775, doi:10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- Ayesha Jalal (4 January 2002). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. pp. 415–. ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0.

- Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4.

- Pakistan Historical Society (2007). Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. Pakistan Historical Society. p. 245.

- Ansari, p. 77.

- Ansari, p. 115.

- I. Malik (3 June 1999). Islam, Nationalism and the West: Issues of Identity in Pakistan. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0.

- Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003). Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises. SAGE Publications. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5.

- "Socail Policy and Development Centre |" (PDF). www.spdc.org.pk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2009.

- Rahimdad Khan Molai Shedai; Janet ul Sindh; 3rd edition, 1993; Sindhi Adbi Board, Jamshoro; page no: 2.

- "Religion in Pakistan (2017 Census)" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Annemarie Schimmel, Pearls from Indus Jamshoro, Sindh, Pakistan: Sindhi Adabi Board (1986). See pp. 150.

- "History of Sufism in Sindh discussed". DAWN.COM. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Can Sufism save Sindh?". DAWN.COM. 2 February 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Thar: where Muslims and Hindus live in complete religious harmony". The news on Sunday. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Raza, Hassan (5 March 2015). "Mithi:Where a Hindu fasts and a Muslim does not slaughter cows". Dawn news.

- Tunio, Hafeez (31 May 2020). "Shikarpur's Sikhs serve humanity beyond religion". The Express Tribune. Pakistan. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". dawn.com. dawn. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Rehman, Zia Ur (18 August 2015). "With a handful of subbers, two newspapers barely keeping Gujarati alive in Karachi". The News International. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

In Pakistan, the majority of Gujarati-speaking communities are in Karachi including Dawoodi Bohras, Ismaili Khojas, Memons, Kathiawaris, Katchhis, Parsis (Zoroastrians) and Hindus, said Gul Hasan Kalmati, a researcher who authored "Karachi, Sindh Jee Marvi", a book discussing the city and its indigenous communities. Although there are no official statistics available, community leaders claim that there are three million Gujarati-speakers in Karachi – roughly around 15 percent of the city's entire population.

- Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2019). "Pakistan - Languages". Ethnologue (22nd ed.).

- Karachi in the Twenty-First Century: Political, Social, Economic and Security Dimensions. 22 February 2016. ISBN 9781443889346.

- "Political and ethnic battles turn Karachi into Beirut of South Asia " Crescent". Merinews.com. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Menon, Sunita. "Queen of Mangoes: Sindhri from Pakistan now in UAE". Khaleej Times. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Pakistan Bureau of Statistics – 6th Population and Housing Census". www.pbscensus.gov.pk.

- Ilyas, Faiza (10 July 2012). "Provincial mammal, bird notified". Dawn. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Govt declares Neem 'provincial tree'". Dawn. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Amar Guriro (14 December 2011). "Our Sindhi symbols – ibex, black partridge". Pakistan Today. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Sheikh, Yasir (5 November 2012). "Areas of political influence in Pakistan: right-wing vs left-wing". Karachi, Sindh: Rug Pandits, Yasir. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Rehman, Zia ur (26 May 2015). "PML-N braving silent rebellion in Sindh and Karachi leaderships". News International. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Sodhar, Muhammad Qasim. "Turn Right: Sindhi Nationalism and Electoral Politics". Tanqeed, Sodhar. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Commissionerate system restored". Archived from the original on 9 January 2010.

- "502 Bad Gateway". www.emoiz.com.

- "Commissioner system to be restored soon: Durrani". Archived from the original on 31 July 2012.

- "Sindh: Commissioner system may be revived today".

- "Commissioners, DCs posted in Sindh". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- "Sindh back to 5 divisions after 11 years | Pakistan Today". www.pakistantoday.com.pk.

- "Northern Punjab, urban Sindh people more prosperous than rest of country: report". Express Tribune. 20 June 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Gazetteer of the Province of Sind …. government at the "Mercantile" steam Press. 1907.

- "About Sindh". Consulate General of the People's Republic of China in Karachi. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "Population by Level of Education and Rural/Urban". Statistics Division: Ministry of Economic Affairs and Statistics. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- "Spotlighting: Sindh Exhibit provides peek into province's rich culture – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "Cultural Heritage". wishwebdesign.com =. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- "Sindh celebrates first ever 'Sindhi Topi Day'".

Bibliography

- Ansari, Sarah F.D. (1992) Sufi saints and state power: the pirs of Sind, 1843–1947, No. 50. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 9780511563201.

- Phiroze Vasunia (16 May 2013), The Classics and Colonial India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-01-9920-323-9

- Malkani, Kewal Ram (1984). The Sindh Story. Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

.jpg)