Kolkata

Kolkata (/kɒlˈkɑːtə/[15] or /kɒlˈkʌtə/,[16] Bengali: [ˈkolˌkata] (![]()

Kolkata Calcutta | |

|---|---|

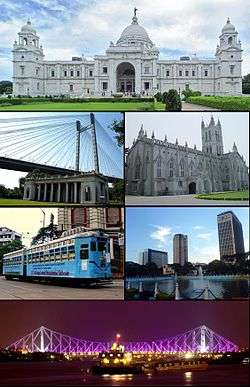

Clockwise from top: Victoria Memorial, St. Paul's Cathedral, Central Business District, Rabindra Setu, City Tram Line, Vidyasagar Setu | |

| Nickname(s): Cultural Capital of India[1] | |

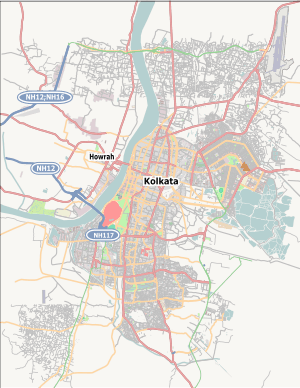

Kolkata Location in West Bengal, India  Kolkata Kolkata (West Bengal)  Kolkata Kolkata (India)  Kolkata Kolkata (Asia) .svg.png) Kolkata Kolkata (Earth) | |

| Coordinates: 22.5726°N 88.3639°E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Division | Presidency |

| District | Kolkata[2][3][4][5][6][upper-alpha 1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Body | Kolkata Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Firhad Hakim (AITC) |

| • Sheriff | Mani Shankar Mukherjee |

| • Police commissioner | Anuj Sharma, IPS |

| Area | |

| • Megacity | 206.08 km2 (79.151 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,886.67 km2 (728.45 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 9 m (30 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Megacity | 4,496,694 |

| • Rank | 7th |

| • Density | 22,000/km2 (57,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 14,112,536 14,617,882 (Extended UA) |

| • Metro rank | 3rd |

| Demonyms | Kolkatan Calcuttan |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bengali • English[12] |

| • Additional official | Hindi • Urdu • Nepali • Odia • Santali • Punjabi • Kamtapuri • Rajbanshi • Kurmali[12] |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ZIP code(s) | 700 xxx |

| Area code(s) | +91-33 |

| Vehicle registration | WB-01 to WB-10 |

| UN/LOCODE | IN CCU |

| Metro GDP/PPP | $60–$150 billion[13] |

| HDI (2004) | |

| Website | kmcgov.in |

| |

In the late 17th century, the three villages that predated Calcutta were ruled by the Nawab of Bengal under Mughal suzerainty. After the Nawab granted the East India Company a trading licence in 1690,[17] the area was developed by the Company into an increasingly fortified trading post. Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah occupied Calcutta in 1756, and the East India Company retook it the following year. In 1793 the East India company was strong enough to abolish rule, and assumed full sovereignty of the region. Under the company rule and later under the British Raj, Calcutta served as the capital of British-held territories in India until 1911, when its perceived geographical disadvantages, combined with growing nationalism in Bengal, led to a shift of the capital to New Delhi. Calcutta was the centre for the Indian independence movement. Following independence in 1947, Kolkata, which was once the centre of Indian commerce, culture, and politics, suffered many decades of political violence and economic stagnation.[18]

A demographically diverse city, the culture of Kolkata features idiosyncrasies that include distinctively close-knit neighbourhoods (paras) and freestyle conversations (adda). Kolkata is home to West Bengal's film industry Tollywood, and cultural institutions, such as the Academy of Fine Arts, the Victoria Memorial, the Asiatic Society, the Indian Museum and the National Library of India. Among scientific institutions, Kolkata hosts the Agri Horticultural Society of India, the Geological Survey of India, the Botanical Survey of India, the Calcutta Mathematical Society, the Indian Science Congress Association, the Zoological Survey of India, the Institution of Engineers, the Anthropological Survey of India and the Indian Public Health Association. Though home to major cricketing venues and franchises, Kolkata differs from other Indian cities by focusing on association football and other sports.

Etymology

The word Kolkata (Bengali: কলকাতা [ˈkolˌkata]) derives from Kôlikata (Bengali: কলিকাতা [ˈkɔliˌkata]), the Bengali name of one of three villages that predated the arrival of the British, in the area where the city was eventually established; the other two villages were Sutanuti and Govindapur.[19]

There are several explanations for the etymology of this name:

- Kolikata is thought to be a variation of Kalikkhetrô (Bengali: কালীক্ষেত্র [ˈkaliˌkʰːetrɔ]), meaning "Field of [the goddess] Kali". Similarly, it can be a variation of 'Kalikshetra' (Sanskrit: कालीक्षेत्र, lit. "area of Goddess Kali").

- Another theory is that the name derives from Kalighat.[20]

- Alternatively, the name may have been derived from the Bengali term kilkila (Bengali: কিলকিলা), or "flat area".[21]

- The name may have its origin in the words khal (Bengali: খাল [ˈkʰal]) meaning "canal", followed by kaṭa (Bengali: কাটা [ˈkaʈa]), which may mean "dug".[22]

- According to another theory, the area specialised in the production of quicklime or koli chun (Bengali: কলি চুন [ˈkɔliˌtʃun]) and coir or kata (Bengali: কাতা [ˈkata]); hence, it was called Kolikata).[21]

Although the city's name has always been pronounced Kolkata or Kôlikata in Bengali, the anglicised form Calcutta was the official name until 2001, when it was changed to Kolkata in order to match Bengali pronunciation.[23]

History

British colonial rule

The discovery and archaeological study of Chandraketugarh, 35 kilometres (22 mi) north of Kolkata, provide evidence that the region in which the city stands has been inhabited for over two millennia.[24][25] Kolkata's recorded history began in 1690 with the arrival of the English East India Company, which was consolidating its trade business in Bengal. Job Charnock, an administrator who worked for the company, was formerly credited as the founder of the city;[26] In response to a public petition,[27] the Calcutta High Court ruled in 2003 that the city does not have a founder.[28] The area occupied by the present-day city encompassed three villages: Kalikata, Gobindapur and Sutanuti. Kalikata was a fishing village; Sutanuti was a riverside weavers' village. They were part of an estate belonging to the Mughal emperor; the jagirdari (a land grant bestowed by a king on his noblemen) taxation rights to the villages were held by the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family of landowners, or zamindars. These rights were transferred to the East India Company in 1698.[29]:1

In 1712, the British completed the construction of Fort William, located on the east bank of the Hooghly River to protect their trading factory.[30] Facing frequent skirmishes with French forces, the British began to upgrade their fortifications in 1756. The Nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud-Daulah, condemned the militarisation and tax evasion by the company. His warning went unheeded, and the Nawab attacked; he captured Fort William which led to the killings of several East India company officials in the Black Hole of Calcutta.[31] A force of Company soldiers (sepoys) and British troops led by Robert Clive recaptured the city the following year.[31] Per the 1765 Treaty of Allahabad following the battle of Buxar, East India company was appointed imperial tax collector of the Mughal emperor in the province of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, while Mughal-appointed Nawabs continued to rule the province.[32] Declared a presidency city, Calcutta became the headquarters of the East India Company by 1773.[33]

In 1793, ruling power of the Nawabs were abolished and East India company took complete control of the city and the province. In the early 19th century, the marshes surrounding the city were drained; the government area was laid out along the banks of the Hooghly River. Richard Wellesley, Governor-General of the Presidency of Fort William between 1797 and 1805, was largely responsible for the development of the city and its public architecture.[34] Throughout the late 18th and 19th century, the city was a centre of the East India Company's opium trade.[35] A census in 1837 records the population of the city proper as 229,700, of which the British residents made up only 3,138.[36] The same source says another 177,000 resided in the suburbs and neighbouring villages, making the entire population of greater Calcutta 406,700.

In 1864, a typhoon struck the city and killed about 60,000 in Kolkata.[37]

By the 1850s, Calcutta had two areas: White Town, which was primarily British and centred on Chowringhee and Dalhousie Square; and Black Town, mainly Indian and centred on North Calcutta.[38] The city underwent rapid industrial growth starting in the early 1850s, especially in the textile and jute industries; this encouraged British companies to massively invest in infrastructure projects, which included telegraph connections and Howrah railway station. The coalescence of British and Indian culture resulted in the emergence of a new babu class of urbane Indians, whose members were often bureaucrats, professionals, newspaper readers, and Anglophiles; they usually belonged to upper-caste Hindu communities.[39] In the 19th century, the Bengal Renaissance brought about an increased sociocultural sophistication among city denizens. In 1883, Calcutta was host to the first national conference of the Indian National Association, the first avowed nationalist organisation in India.[40]

_and_Strand_Road%2C_Calcutta_in_1945.jpg)

.jpg)

The partition of Bengal in 1905 along religious lines led to mass protests, making Calcutta a less hospitable place for the British.[41][42] The capital was moved to New Delhi in 1911.[43] Calcutta continued to be a centre for revolutionary organisations associated with the Indian independence movement. The city and its port were bombed several times by the Japanese between 1942 and 1944, during World War II.[44][45] Coinciding with the war, millions starved to death during the Bengal famine of 1943 due to a combination of military, administrative, and natural factors.[46] Demands for the creation of a Muslim state led in 1946 to an episode of communal violence that killed over 4,000.[47][48][49] The partition of India led to further clashes and a demographic shift—many Muslims left for East Pakistan (present day Bangladesh), while hundreds of thousands of Hindus fled into the city.[50]

Contemporary

During the 1960s and 1970s, severe power shortages, strikes and a violent Marxist–Maoist movement by groups known as the Naxalites damaged much of the city's infrastructure, resulting in economic stagnation.[18] The Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 led to a massive influx of thousands of refugees, many of them penniless, that strained Kolkata's infrastructure.[51] During the mid-1980s, Mumbai (then called Bombay) overtook Kolkata as India's most populous city. In 1985, prime minister Rajiv Gandhi dubbed Kolkata a "dying city" in light of its socio-political woes.[52] In the period 1977–2011, West Bengal was governed from Kolkata by the Left Front, which was dominated by the Communist Party of India (CPM). It was the world's longest-serving democratically elected communist government, during which Kolkata was a key base for Indian communism.[53][54][55] In the 2011 West Bengal Legislative Assembly election, Left Front was defeated by the Trinamool Congress. The city's economic recovery gathered momentum after the 1990s, when India began to institute pro-market reforms. Since 2000, the information technology (IT) services sector has revitalised Kolkata's stagnant economy. The city is also experiencing marked growth in its manufacturing base.[56]

Geography

Spread roughly north–south along the east bank of the Hooghly River, Kolkata sits within the lower Ganges Delta of eastern India approximately 75 km (47 mi) west of the international border with Bangladesh; the city's elevation is 1.5–9 m (5–30 ft).[57] Much of the city was originally a wetland that was reclaimed over the decades to accommodate a burgeoning population.[58] The remaining undeveloped areas, known as the East Kolkata Wetlands, were designated a "wetland of international importance" by the Ramsar Convention (1975).[59] As with most of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the soil and water are predominantly alluvial in origin. Kolkata is located over the "Bengal basin", a pericratonic tertiary basin.[60] Bengal basin comprises three structural units: shelf or platform in the west; central hinge or shelf/slope break; and deep basinal part in the east and southeast. Kolkata is located atop the western part of the hinge zone which is about 25 km (16 mi) wide at a depth of about 45,000 m (148,000 ft) below the surface.[60] The shelf and hinge zones have many faults, among them some are active. Total thickness of sediment below Kolkata is nearly 7,500 m (24,600 ft) above the crystalline basement; of these the top 350–450 m (1,150–1,480 ft) is Quaternary, followed by 4,500–5,500 m (14,760–18,040 ft) of Tertiary sediments, 500–700 m (1,640–2,300 ft) trap wash of Cretaceous trap and 600–800 m (1,970–2,620 ft) Permian-Carboniferous Gondwana rocks.[60] The quaternary sediments consist of clay, silt and several grades of sand and gravel. These sediments are sandwiched between two clay beds: the lower one at a depth of 250–650 m (820–2,130 ft); the upper one 10–40 m (30–130 ft) in thickness.[61] According to the Bureau of Indian Standards, on a scale ranging from I to V in order of increasing susceptibility to earthquakes, the city lies inside seismic zone III.[62]

Urban structure

The Kolkata metropolitan area is spread over 1,886.67 km2 (728.45 sq mi)[63]:7 and comprises 4 municipal corporations (including Kolkata Municipal Corporation), 37 local municipalities and 24 panchayat samitis, as of 2011.[63]:7 The urban agglomeration encompassed 72 cities and 527 towns and villages, as of 2006.[64] Suburban areas in the Kolkata metropolitan area incorporate parts of the following districts: North 24 Parganas, South 24 Parganas, Howrah, Hooghly and Nadia.[65]:15 Kolkata, which is under the jurisdiction of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC), has an area of 206.08 km2 (80 sq mi).[64] The east–west dimension of the city is comparatively narrow, stretching from the Hooghly River in the west to roughly the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass in the east—a span of 9–10 km (5.6–6.2 mi).[66] The north–south distance is greater, and its axis is used to section the city into North, Central, South and East Kolkata.

North Kolkata is the oldest part of the city. Characterised by 19th-century architecture and narrow alleyways, it includes areas such as Jorasanko, Rajabazar, Maniktala, Ultadanga, Shyambazar, Shobhabazar, Bagbazar, Cossipore, Sinthee etc. The north suburban areas like Dum Dum, Baranagar, Belgharia, Sodepur, Khardaha, New Barrackpore, Madhyamgram, Barrackpore, Barasat etc. are also within the city of Kolkata (as a metropolitan structure).[65]:65–66 Central Kolkata hosts the central business district. It contains B.B.D. Bagh, formerly known as Dalhousie Square, and the Esplanade on its east; Strand Road is on its west.[67] The West Bengal Secretariat, General Post Office, Reserve Bank of India, Calcutta High Court, Lalbazar Police Headquarters and several other government and private offices are located there. Another business hub is the area south of Park Street, which comprises thoroughfares such as Chowringhee Road, Camac Street, Wood Street, Loudon Street, Shakespeare Sarani and AJC Bose Road.[68] South Kolkata developed after India gained independence in 1947; it includes upscale neighbourhoods such as Bhawanipore, Alipore, Ballygunge, Kasba, Dhakuria, Santoshpur, Garia, Golf Green, Tollygunge, New Alipore, Behala etc. The south suburban areas like Maheshtala, Budge Budge, Rajpur Sonarpur, Baruipur etc. are also within the city of Kolkata (as a metropolitan structure).[19] The Maidan is a large open field in the heart of the city that has been called the "lungs of Kolkata"[69] and accommodates sporting events and public meetings.[70] The Victoria Memorial and Kolkata Race Course are located at the southern end of the Maidan. Among the other parks are Central Park in Bidhannagar and Millennium Park on Strand Road, along the Hooghly River.

Two planned townships in the greater Kolkata region are Bidhannagar, also known as Salt Lake City and located north-east of the city; and Rajarhat, also called New Town and located east of Bidhannagar.[19][71] In the 2000s, Sector V in Bidhannagar developed into a business hub for information technology and telecommunication companies.[72][73] Both Bidhannagar and New Town are situated outside the Kolkata Municipal Corporation limits, in their own municipalities.[71]

Climate

Kolkata is subject to a tropical wet-and-dry climate that is designated Aw under the Köppen climate classification. According to a United Nations Development Programme report, its wind and cyclone zone is "very high damage risk".[62]

Temperature

The annual mean temperature is 26.8 °C (80.2 °F); monthly mean temperatures are 19–30 °C (66–86 °F). Summers (March–June) are hot and humid, with temperatures in the low 30s Celsius; during dry spells, maximum temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F) in May and June.[74] Winter lasts for roughly two-and-a-half months, with seasonal lows dipping to 9–11 °C (48–52 °F) in December and January. May is the hottest month, with daily temperatures ranging from 27–37 °C (81–99 °F); January, the coldest month, has temperatures varying from 12–23 °C (54–73 °F). The highest recorded temperature is 43.9 °C (111.0 °F), and the lowest is 5 °C (41 °F).[74] The winter is mild and very comfortable weather pertains over the city throughout this season. Often, in April–June, the city is struck by heavy rains or dusty squalls that are followed by thunderstorms or hailstorms, bringing cooling relief from the prevailing humidity. These thunderstorms are convective in nature, and are known locally as kal bôishakhi (কালবৈশাখী), or "Nor'westers" in English.[75]

Rainfall

Rains brought by the Bay of Bengal branch of the south-west summer monsoon[76] lash Kolkata between June and September, supplying it with most of its annual rainfall of about 1,850 mm (73 in). The highest monthly rainfall total occurs in July and August. In these months often incessant rain for days brings life to a stall for the city dwellers. The city receives 2,107 hours of sunshine per year, with maximum sunlight exposure occurring in April.[77] Kolkata has been hit by several cyclones; these include systems occurring in 1737 and 1864 that killed thousands.[78][79] In 2009, Severe Cyclone Aila and in 2020 Extremely Severe Cyclone Amphan caused widespread damage to Kolkata by bringing catastrophic winds and torrential rainfall.

Climate data for Kolkata (Alipore) 1981–2010, extremes 1901–2012 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.8 (91.0) |

38.4 (101.1) |

41.1 (106.0) |

43.3 (109.9) |

43.7 (110.7) |

43.9 (111.0) |

39.9 (103.8) |

38.4 (101.1) |

38.9 (102.0) |

39.0 (102.2) |

34.9 (94.8) |

32.5 (90.5) |

43.9 (111.0) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 29.8 (85.6) |

33.5 (92.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

38.8 (101.8) |

38.0 (100.4) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.0 (95.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

32.9 (91.2) |

29.8 (85.6) |

39.8 (103.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 25.8 (78.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

33.5 (92.3) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.3 (95.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.2 (90.0) |

30.1 (86.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

31.6 (88.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

25.0 (77.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

27.1 (80.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.1 (57.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.2 (59.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 10.7 (51.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.2 (63.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 10.4 (0.41) |

20.9 (0.82) |

35.2 (1.39) |

58.9 (2.32) |

133.1 (5.24) |

300.6 (11.83) |

396.0 (15.59) |

344.5 (13.56) |

318.1 (12.52) |

180.5 (7.11) |

35.1 (1.38) |

3.2 (0.13) |

1,836.5 (72.30) |

| Average rainy days | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 7.0 | 12.8 | 17.7 | 16.9 | 13.9 | 7.4 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 85.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 61 | 54 | 51 | 62 | 68 | 77 | 82 | 83 | 82 | 75 | 67 | 65 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 213.9 | 211.9 | 229.4 | 240.0 | 232.5 | 135.0 | 105.4 | 117.8 | 126.0 | 201.5 | 216.0 | 204.6 | 2,234 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.9 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 8.0 | 7.5 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 6.1 |

| Source 1: India Meteorological Department (sun 1971–2000)[80][81][82] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Tokyo Climate Center (mean temperatures 1981–2010)[83] | |||||||||||||

Environmental issues

Pollution is a major concern in Kolkata. As of 2008, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide annual concentration were within the national ambient air quality standards of India, but respirable suspended particulate matter levels were high, and on an increasing trend for five consecutive years, causing smog and haze.[84][85] Severe air pollution in the city has caused a rise in pollution-related respiratory ailments, such as lung cancer.[86]

Economy

_building%2C_September_2011.jpg)

Kolkata is the commercial and financial hub of East and North-East India[65] and home to the Calcutta Stock Exchange.[87][88] It is a major commercial and military port, and is the only city in eastern India, apart from Bhubaneswar to have an international airport. Once India's leading city, Kolkata experienced a steady economic decline in the decades following India's independence due to steep population increases and a rise in militant trade-unionism, which included frequent strikes that were backed by left-wing parties.[56] From the 1960s to the late 1990s, several factories were closed and businesses relocated.[56] The lack of capital and resources added to the depressed state of the city's economy and gave rise to an unwelcome sobriquet: the "dying city".[89] The city's fortunes improved after the Indian economy was liberalised in the 1990s and changes in economic policy were enacted by the West Bengal state government.[56] Recent estimates of the economy of Kolkata's metropolitan area have ranged from $60 to $150 billion (PPP GDP), and have ranked it third-most productive metro area of India.[13]

Flexible production has been the norm in Kolkata, which has an informal sector that employs more than 40% of the labour force.[19] One unorganised group, roadside hawkers, generated business worth ₹ 87.72 billion (US$ 2 billion) in 2005.[90] As of 2001, around 0.81% of the city's workforce was employed in the primary sector (agriculture, forestry, mining, etc.); 15.49% worked in the secondary sector (industrial and manufacturing); and 83.69% worked in the tertiary sector (service industries).[65]:19 As of 2003, the majority of households in slums were engaged in occupations belonging to the informal sector; 36.5% were involved in servicing the urban middle class (as maids, drivers, etc.) and 22.2% were casual labourers.[91]:11 About 34% of the available labour force in Kolkata slums were unemployed.[91]:11 According to one estimate, almost a quarter of the population live on less than 27 rupees (equivalent to 45 US cents) per day.[92]

As in many other Indian cities, information technology became a high-growth sector in Kolkata starting in the late 1990s; the city's IT sector grew at 70% per annum—a rate that was twice the national average.[56] The 2000s saw a surge of investments in the real estate, infrastructure, retail, and hospitality sectors; several large shopping malls and hotels were launched.[93][94][95][96][97] Companies such as ITC Limited, CESC Limited, Exide Industries, Emami, Eveready Industries India, Lux Industries, Rupa Company, Berger Paints, Birla Corporation and Britannia Industries are headquartered in the city. Philips India, PricewaterhouseCoopers India, Tata Global Beverages, Tata Steel have their registered office and zonal headquarters in Kolkata. Kolkata hosts the headquarters of three major public-sector banks: Allahabad Bank, UCO Bank, and the United Bank of India; and a private bank Bandhan Bank. Reserve Bank of India has its eastern zonal office in Kolkata, and India Government Mint, Kolkata is one of the four mints in India. Some of the oldest public sector companies are headquartered in the city such as the Coal India Limited, National Insurance Company, Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers, Tea Board of India, Geological Survey of India, Zoological Survey of India, Botanical Survey of India, Jute Corporation of India, National Test House, Hindustan Copper and the Ordnance Factories Board of the Indian Ministry of Defence.

Demographics

| Population of Kolkata | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1901 | 1,009,853 | — | |

| 1911 | 1,117,966 | 10.7% | |

| 1921 | 1,158,497 | 3.6% | |

| 1931 | 1,289,461 | 11.3% | |

| 1941 | 2,352,399 | 82.4% | |

| 1951 | 2,956,475 | 25.7% | |

| 1961 | 3,351,250 | 13.4% | |

| 1971 | 3,727,020 | 11.2% | |

| 1981 | 4,126,846 | 10.7% | |

| 1991 | 4,399,819 | 6.6% | |

| 2001 | 4,572,876 | 3.9% | |

| 2011 | 4,496,694 | −1.7% | |

| source:[98] | |||

The demonym for residents of Kolkata are Calcuttan and Kolkatan.[99][100] According to provisional results of the 2011 national census, Kolkata district, which occupies an area of 185 km2 (71 sq mi), had a population of 4,486,679;[101] its population density was 24,252/km2 (62,810/sq mi).[101] This represents a decline of 1.88% during the decade 2001–11. The sex ratio is 899 females per 1000 males—lower than the national average.[102] The ratio is depressed by the influx of working males from surrounding rural areas, from the rest of West Bengal; these men commonly leave their families behind.[103] Kolkata's literacy rate of 87.14%[102] exceeds the national average of 74%.[104] The final population totals of census 2011 stated the population of city as 4,496,694.[9] The urban agglomeration had a population of 14,112,536 in 2011.[10]

Bengali Hindus form the majority of Kolkata's population; Marwaris, Biharis and Muslims compose large minorities.[105] Among Kolkata's smaller communities are Chinese, Tamils, Nepalis, Pathans/Afghans (locally known as Kabuliwala[106]) Odias, Telugus, Assamese, Gujaratis, Anglo-Indians, Armenians, Greeks, Tibetans, Maharashtrians, Konkanis, Malayalees, Punjabis and Parsis.[29]:3 The number of Armenians, Greeks, Jews and other foreign-origin groups declined during the 20th century.[107] The Jewish population of Kolkata was 5,000 during World War II, but declined after Indian independence and the establishment of Israel;[108] by 2013, there were 25 Jews in the city.[109] India's sole Chinatown is in eastern Kolkata;[107] once home to 20,000 ethnic Chinese, its population dropped to around 2,000 as of 2009[107] as a result of multiple factors including repatriation and denial of Indian citizenship following the 1962 Sino-Indian War, and immigration to foreign countries for better economic opportunities.[110] The Chinese community traditionally worked in the local tanning industry and ran Chinese restaurants.[107][111]

| ||||||||||||||||||

Bengali, the official state language, is the dominant language in Kolkata.[113] English is also used, particularly by the white-collar workforce. Hindi and Urdu are spoken by a sizeable minority.[114][115] According to the 2011 census, 76.51% of the population is Hindu, 20.60% Muslim, 0.88% Christian and 0.47% Jain.[116] The remainder of the population includes Sikhs, Buddhists, and other religions which accounts for 0.45% of the population; 1.09% did not state a religion in the census.[116] Kolkata reported 67.6% of Special and Local Laws crimes registered in 35 large Indian cities during 2004.[117] The Kolkata police district registered 15,510 Indian Penal Code cases in 2010, the 8th-highest total in the country.[118] In 2010, the crime rate was 117.3 per 100,000, below the national rate of 187.6; it was the lowest rate among India's largest cities.[119]

As of 2003, about one-third of the population, or 1.5 million people, lived in 3,500 unregistered squatter-occupied and 2,011 registered slums.[91]:4[120]:92 The authorised slums (with access to basic services like water, latrines, trash removal by the Kolkata Municipal Corporation) can be broadly divided into two groups—bustees, in which slum dwellers have some long term tenancy agreement with the landowners; and udbastu colonies, settlements which had been leased to refugees from present-day Bangladesh by the government.[120][91]:5 The unauthorised slums (devoid of basic services provided by the municipality) are occupied by squatters who started living on encroached lands—mainly along canals, railway lines and roads.[120]:92[91]:5 According to the 2005 National Family Health Survey, around 14% of the households in Kolkata were poor, while 33% lived in slums, indicating a substantial proportion of households in slum areas were better off economically than the bottom quarter of urban households in terms of wealth status.[121]:23 Mother Teresa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for founding and working with the Missionaries of Charity in Kolkata—an organisation "whose primary task was to love and care for those persons nobody was prepared to look after".[122]

Government and public services

Civic administration

Kolkata is administered by several government agencies. The Kolkata Municipal Corporation, or KMC, oversees and manages the civic infrastructure of the city's 16 boroughs, which together encompass 144 wards.[113] Each ward elects a councillor to the KMC. Each borough has a committee of councillors, each of whom is elected to represent a ward. By means of the borough committees, the corporation undertakes urban planning and maintains roads, government-aided schools, hospitals, and municipal markets.[123] As Kolkata's apex body, the corporation discharges its functions through the mayor-in-council, which comprises a mayor, a deputy mayor, and ten other elected members of the KMC.[124] The functions of the KMC include water supply, drainage and sewerage, sanitation, solid waste management, street lighting, and building regulation.[123]

Kolkata's administrative agencies have areas of jurisdiction that do not coincide. Listed in ascending order by area, they are: Kolkata district; the Kolkata Police area and the Kolkata Municipal Corporation area, or "Kolkata city";[125] and the Kolkata metropolitan area, which is the city's urban agglomeration. The agency overseeing the latter, the Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority, is responsible for the statutory planning and development of greater Kolkata.[126] The Kolkata Municipal Corporation was ranked 1st out of 21 Cities for best governance & administrative practices in India in 2014. It scored 4.0 on 10 compared to the national average of 3.3.[127]

The Kolkata Port Trust, an agency of the central government, manages the city's river port. As of 2012, the All India Trinamool Congress controls the KMC; the mayor is Firhad Hakim, while the deputy mayor is Atin Ghosh.[128] The city has an apolitical titular post, that of the Sheriff of Kolkata, which presides over various city-related functions and conferences.[129]

As the seat of the Government of West Bengal, Kolkata is home to not only the offices of the local governing agencies, but also the West Bengal Legislative Assembly; the state secretariat, which is housed in the Writers' Building; and the Calcutta High Court. Most government establishments and institutions are housed in the centre of the city in B. B. D. Bagh (formerly known as Dalhousie Square). The Calcutta High Court is the oldest High Court in India. It was preceded by the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William which was established in 1774. The Calcutta High Court has jurisdiction over the state of West Bengal and the Union Territory of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Kolkata has lower courts: the Court of Small Causes and the City Civil Court decide civil matters; the Sessions Court rules in criminal cases.[130][131][132] The Kolkata Police, headed by a police commissioner, is overseen by the West Bengal Ministry of Home Affairs.[133][134] The Kolkata district elects two representatives to India's lower house, the Lok Sabha, and 11 representatives to the state legislative assembly.[135]

Utility services

The Kolkata Municipal Corporation supplies the city with potable water that is sourced from the Hooghly River;[136] most of it is treated and purified at the Palta pumping station located in North 24 Parganas district.[137] Roughly 95% of the 4,000 tonnes of refuse produced daily by the city is transported to the dumping grounds in Dhapa, which is east of the town.[138][139] To promote the recycling of garbage and sewer water, agriculture is encouraged on the dumping grounds.[140] Parts of the city lack proper sewerage, leading to unsanitary methods of waste disposal.[77]

In 1856 the Bengal Government appointed George Turnbull to be the Commissioner of Drainage and Sewerage to improve the city's sewerage. Turnbull's main job was to be the Chief Engineer of the East Indian Railway Company responsible for building the first railway 541 miles from Howrah to Varanasi (then Benares).

Electricity is supplied by the privately operated Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation, or CESC, to the city proper; the West Bengal State Electricity Board supplies it in the suburbs.[141][142] Fire services are handled by the West Bengal Fire Service, a state agency.[143] As of 2012, the city had 16 fire stations.[144]

State-owned Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited, or BSNL, as well as private enterprises, among them Vodafone, Bharti Airtel, Reliance, Idea Cellular, Aircel, Tata DoCoMo, Tata Teleservices, Virgin Mobile, and MTS India, are the leading telephone and cell phone service providers in the city.[145]:25–26:179 with Kolkata being the first city in India to have cell phone and 4G connectivity, the GSM and CDMA cellular coverage is extensive.[146][147] As of 2010, Kolkata has 7 percent of the total Broadband internet consumers in India; BSNL, VSNL, Tata Indicom, Sify, Airtel, and Reliance are among the main vendors.[148][149]

Military and diplomatic establishments

The Eastern Command of the Indian Army is based in the city. Being one of India's major city and the largest city in eastern and north-eastern India, Kolkata hosts diplomatic missions of many countries such as Australia, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Canada, People's Republic of China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Myanmar, Nepal, Russia, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Thailand, United Kingdom and United States. The U.S Consulate in Kolkata is the US Department of State's second-oldest Consulate and dates from 19 November 1792.[150] The Diplomatic representation of more than 65 Countries and International Organization is present in Kolkata as Consulate office, honorary Consulate office, Cultural Centre, Deputy High Commission and Economic section and Trade Representation office.[151]

Transport

.jpg)

_03.jpg)

Public transport is provided by the Kolkata Suburban Railway, the Kolkata Metro, trams, rickshaws, taxis and buses. The suburban rail network connects the city's distant suburbs.

According to a 2013 survey conducted by the International Association of Public Transport, in terms of a public transport system, Kolkata ranks among the top of the six Indian cities surveyed.[152][153] The Kolkata Metro, in operation since 1984, is the oldest underground mass transit system in India.[154] It spans the north–south length of the city. In 2020, part of the Second line was inaugurated to cover part of Salt Lake. This east–west line will connect Salt Lake with Howrah The 2 lines cover a distance of 33.02 km (21 mi). As of 2020, four Metro rail lines were under construction.[155] Kolkata has five long-distance railway stations, located at Howrah (the largest railway complex in India), Sealdah, Chitpur, Shalimar and Santragachi, which connect Kolkata by rail to most cities in West Bengal and to other major cities in India.[156] The city serves as the headquarters of three railway Zone out of Eighteen of the Indian Railways regional divisions—the Kolkata Metro Railways, Eastern Railway and the South-Eastern Railway.[157] Kolkata has rail and road connectivity with Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh.[158][159][160]

Buses, which are the most commonly used mode of transport, are run by government agencies and private operators.[161] Kolkata is the only Indian city with a tram network, which is operated by the Calcutta Tramways Company.[162] The slow-moving tram services are restricted to certain areas of the city. Water-logging, caused by heavy rains during the summer monsoon, sometimes interrupt transportation networks.[163][164] Hired public conveyances include auto rickshaws, which often ply specific routes, and yellow metered taxis. Almost all of Kolkata's taxis are antiquated Hindustan Ambassadors by make; newer air-conditioned radio taxis are in service as well.[165][166] In parts of the city, cycle rickshaws and hand-pulled rickshaws are patronised by the public for short trips.[167]

Due to its diverse and abundant public transportation, privately owned vehicles are not as common in Kolkata as in other major Indian cities.[168] The city has witnessed a steady increase in the number of registered vehicles; 2002 data showed an increase of 44% over a period of seven years.[169] As of 2004, after adjusting for population density, the city's "road space" was only 6% compared to 23% in Delhi and 17% in Mumbai.[170] The Kolkata Metro has somewhat eased traffic congestion, as has the addition of new roads and flyovers. Agencies operating long-distance bus services include the Calcutta State Transport Corporation, the South Bengal State Transport Corporation, the North Bengal State Transport Corporation and various private operators. The city's main bus terminals are located at Esplanade and Babughat.[171] The Kolkata–Delhi and Kolkata–Chennai prongs of the Golden Quadrilateral, and National Highway 12 start from the city.[172]

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose International Airport, located in Dum Dum, about 16 km (9.9 mi) north-east of the city centre, operates domestic and international flights. In 2013, the airport was upgraded to handle increased air traffic.[173][174]

The Port of Kolkata, established in 1870, is India's oldest and the only major river port.[175] The Kolkata Port Trust manages docks in Kolkata and Haldia.[176] The port hosts passenger services to Port Blair, capital of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands; freighter service to ports throughout India and around the world is operated by the Shipping Corporation of India.[175][177] Ferry services connect Kolkata with its twin city of Howrah, located across the Hooghly River.[178][179]

Healthcare

As of 2011, the health care system in Kolkata consists of 48 government hospitals, mostly under the Department of Health & Family Welfare, Government of West Bengal, and 366 private medical establishments;[180] these establishments provide the city with 27,687 hospital beds.[180] For every 10,000 people in the city, there are 61.7 hospital beds,[181] which is higher than the national average of 9 hospital beds per 10,000.[182] Ten medical and dental colleges are located in the Kolkata metropolitan area which act as tertiary referral hospitals in the state.[183][184] The Calcutta Medical College, founded in 1835, was the first institution in Asia to teach modern medicine.[185] However, These facilities are inadequate to meet the healthcare needs of the city.[186][187][188] More than 78% in Kolkata prefer the private medical sector over the public medical sector,[121]:109 due to the overburdening of the public health sector, the lack of a nearby facility, and excessive waiting times at government facilities.[121]:61

According to the Indian 2005 National Family Health Survey, only a small proportion of Kolkata households were covered under any health scheme or health insurance.[121]:41 The total fertility rate in Kolkata was 1.4, The lowest among the eight cities surveyed.[121]:45 In Kolkata, 77% of the married women used contraceptives, which was the highest among the cities surveyed, but use of modern contraceptive methods was the lowest (46%).[121]:47 The infant mortality rate in Kolkata was 41 per 1,000 live births, and the mortality rate for children under five was 49 per 1,000 live births.[121]:48

Among the surveyed cities, Kolkata stood second (5%) for children who had not had any vaccinations under the Universal Immunization Programme as of 2005.[121]:48 Kolkata ranked second with access to an anganwadi centre under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme for 57% of the children between 0 and 71 months.[121]:51 The proportion of malnourished, anaemic and underweight children in Kolkata was less in comparison to other surveyed cities.[121]:54–55

About 18% of the men and 30% of the women in Kolkata are obese—the majority of them belonging to the non-poor strata of society.[121]:105 In 2005, Kolkata had the highest percentage (55%) among the surveyed cities of anaemic women, while 20% of the men in Kolkata were anaemic.[121]:56–57 Diseases like diabetes, asthma, goitre and other thyroid disorders were found in large numbers of people.[121]:57–59 Tropical diseases like malaria, dengue and chikungunya are prevalent in Kolkata, though their incidence is decreasing.[189][190] Kolkata is one of the districts in India with a high number of people with AIDS; it has been designated a district prone to high risk.[191][192] As of 2014, because of higher air pollution, the life expectancy of a person born in the city is four years fewer than in the suburbs.[193]

Education

Kolkata's schools are run by the state government or private organisations, many of which are religious. Bengali and English are the primary languages of instruction; Urdu and Hindi are also used, particularly in central Kolkata.[194][195] Schools in Kolkata follow the "10+2+3" plan. After completing their secondary education, students typically enroll in schools that have a higher secondary facility and are affiliated with the West Bengal Council of Higher Secondary Education, the ICSE, or the CBSE.[194] They usually choose a focus on liberal arts, business, or science. Vocational programs are also available.[194] Some Kolkata schools, for example La Martiniere Calcutta, Calcutta Boys' School, South Point School, St. James' School (Kolkata), St. Xavier's Collegiate School and Loreto House, have been ranked amongst the best schools in the country.[196]

As of 2010, the Kolkata urban agglomeration is home to 14 universities run by the state government.[197] The colleges are each affiliated with a university or institution based either in Kolkata or elsewhere in India. Aliah University which was founded in 1780 as Mohammedan College of Calcutta is the oldest post-secondary educational institution of the city.[198] The University of Calcutta, founded in 1857, is the first modern university in South Asia.[199] Presidency College, Kolkata (formerly Hindu College between 1817 and 1855), founded in 1855, was one of the oldest and most eminent colleges in India. It was affiliated with the University of Calcutta until 2010 when it was converted to Presidency University, Kolkata in 2010. Bengal Engineering and Science University (BESU) is the second oldest engineering institution of the country located in Howrah.[200] An Institute of National Importance, BESU was converted to India's first IIEST. Jadavpur University is known for its arts, science, and engineering faculties.[201] The Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, which was the first of the Indian Institutes of Management, was established in 1961 at Joka, a locality in the south-western suburbs. Kolkata also houses the prestigious Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, which was started here in the year 2006.[202] The West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences is one of India's autonomous law schools,[203][204] and the Indian Statistical Institute is a public research institute and university. State owned Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, West Bengal (MAKAUT, WB), formerly West Bengal University of Technology (WBUT) is the largest Technological University in terms of student enrollment and number of Institutions affiliated by it. Private institutions include the Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda Educational and Research Institute and University of Engineering & Management (UEM).

Notable scholars who were born, worked or studied in Kolkata include physicists Satyendra Nath Bose, Meghnad Saha,[205] and Jagadish Chandra Bose;[206] chemist Prafulla Chandra Roy;[205] statisticians Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis and Anil Kumar Gain;[205] physician Upendranath Brahmachari;[205] educator Ashutosh Mukherjee;[207] and Nobel laureates Rabindranath Tagore,[208] C. V. Raman,[206] and Amartya Sen.[209]

Kolkata houses many premier research institutes like Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS), Indian Institute of Chemical Biology (IICB), Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Bose Institute, Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics (SINP), Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, Central Glass and Ceramic Research Institute (CGCRI), S.N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences (SNBNCBS), Indian Institute of Social Welfare and Business Management (IISWBM), National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Kolkata, Variable Energy Cyclotron Centre (VECC) and Indian Centre for Space Physics. Nobel laureate Sir C. V. Raman did his groundbreaking work in Raman effect in IACS.

Culture

Kolkata is known for its literary, artistic and revolutionary heritage; as the former capital of India, it was the birthplace of modern Indian literary and artistic thought.[210] Kolkata has been called the "City of Furious, Creative Energy"[211] as well as the "cultural [or literary] capital of India".[212][213] The presence of paras, which are neighbourhoods that possess a strong sense of community, is characteristic of the city.[214] Typically, each para has its own community club and on occasion, a playing field.[214] Residents engage in addas, or leisurely chats, that often take the form of freestyle intellectual conversation.[215][216] The city has a tradition of political graffiti depicting everything from outrageous slander to witty banter and limericks, caricatures and propaganda.[217][218]

Kolkata has many buildings adorned with Indo-Islamic and Indo-Saracenic architectural motifs. Several well-maintained major buildings from the colonial period have been declared "heritage structures";[219] others are in various stages of decay.[220][221] Established in 1814 as the nation's oldest museum, the Indian Museum houses large collections that showcase Indian natural history and Indian art.[222] Marble Palace is a classic example of a European mansion that was built in the city. The Victoria Memorial, a place of interest in Kolkata, has a museum documenting the city's history. The National Library of India is the leading public library in the country while Science City is the largest science centre in the Indian subcontinent.[223]

The popularity of commercial theatres in the city has declined since the 1980s.[224]:99[225] Group theatres of Kolkata, a cultural movement that started in the 1940s contrasting with the then-popular commercial theatres, are theatres that are not professional or commercial, and are centres of various experiments in theme, content, and production;[226] group theatres use the proscenium stage to highlight socially relevant messages.[224]:99[227] Chitpur locality of the city houses multiple production companies of jatra, a tradition of folk drama popular in rural Bengal.[228][229] Kolkata is the home of the Bengali cinema industry, dubbed "Tollywood" for Tollygunj, where most of the state's film studios are located.[230] Its long tradition of art films includes globally acclaimed film directors such as Academy Award-winning director Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, Tapan Sinha and contemporary directors such as Aparna Sen, Buddhadeb Dasgupta, Goutam Ghose and Rituparno Ghosh.[231] During the 19th and 20th centuries, Bengali literature was modernised through the works of authors such as Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam and Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay.[232] Coupled with social reforms led by Ram Mohan Roy, Swami Vivekananda and others, this constituted a major part of the Bengal Renaissance.[233] The middle and latter parts of the 20th century witnessed the arrival of post-modernism, as well as literary movements such as those espoused by the Kallol movement, hungryalists and the little magazines.[234] Large majority of publishers of the city is concentrated in and around College Street, "... a half-mile of bookshops and bookstalls spilling over onto the pavement", selling new and used books.[235]

Kalighat painting originated in 19th century Kolkata as a local style that reflected a variety of themes including mythology and quotidian life.[236] The Government College of Art and Craft, founded in 1864, has been the cradle as well as workplace of eminent artists including Abanindranath Tagore, Jamini Roy and Nandalal Bose.[237] The art college was the birthplace of the Bengal school of art that arose as an avant garde and nationalist movement reacting against the prevalent academic art styles in the early 20th century.[238][239] The Academy of Fine Arts and other art galleries hold regular art exhibitions. The city is recognised for its appreciation of Rabindra sangeet (songs written by Rabindranath Tagore) and Indian classical music, with important concerts and recitals, such as Dover Lane Music Conference, being held throughout the year; Bengali popular music, including baul folk ballads, kirtans and Gajan festival music; and modern music, including Bengali-language adhunik songs.[240][241] Since the early 1990s, new genres have emerged, including one comprising alternative folk–rock Bengali bands.[240] Another new style, jibonmukhi gaan ("songs about life"), is based on realism.[224]:105 Key elements of Kolkata's cuisine include rice and a fish curry known as machher jhol,[242] which can be accompanied by desserts such as roshogolla, sandesh, and a sweet yoghurt known as mishti dohi. Bengal's large repertoire of seafood dishes includes various preparations of ilish, a fish that is a favourite among Calcuttans. Street foods such as beguni (fried battered eggplant slices), kati roll (flatbread roll with vegetable or chicken, mutton or egg stuffing), phuchka (a deep-fried crêpe with tamarind sauce) and Indian Chinese cuisine from Chinatown are popular.[243][244][245][246]

Though Bengali women traditionally wear the sari, the shalwar kameez and Western attire is gaining acceptance among younger women.[247] Western-style dress has greater acceptance among men, although the traditional dhoti and kurta are seen during festivals. Durga Puja, held in September–October, is Kolkata's most important and largest festival; it is an occasion for glamorous celebrations and artistic decorations.[248][249] The Bengali New Year, known as Poila Boishak, as well as the harvest festival of Poush Parbon are among the city's other festivals; also celebrated are Kali Puja, Diwali, Holi, Jagaddhatri Puja, Saraswati Puja, Rathayatra, Janmashtami, Maha Shivratri, Vishwakarma Puja, Lakshmi Puja, Ganesh Chathurthi, Makar Sankranti, Gajan, Kalpataru Day, Bhai Phonta, Maghotsab, Eid, Muharram, Christmas, Buddha Purnima and Mahavir Jayanti. Cultural events include the Rabindra Jayanti, Independence Day (15 August), Republic Day (26 January), Kolkata Book Fair, the Dover Lane Music Festival, the Kolkata Film Festival, Nandikar's National Theatre Festival, Statesman Vintage & Classic Car Rally and Gandhi Jayanti.

- Dance accompanied by Rabindra Sangeet, a music genre started by Rabindranath Tagore

Dakshineswar Kali Temple, a Hindu temple

Dakshineswar Kali Temple, a Hindu temple

Media

The first newspaper in India, the Bengal Gazette started publishing from the city in 1780.[250] Among Kolkata's widely circulated Bengali-language newspapers are Anandabazar Patrika, Bartaman, Ei Samay Sangbadpatra, Sangbad Pratidin, Aajkaal, Dainik Statesman and Ganashakti.[251] The Statesman and The Telegraph are two major English-language newspapers that are produced and published from Kolkata. Other popular English-language newspapers published and sold in Kolkata include The Times of India, Hindustan Times, The Hindu, The Indian Express and the Asian Age.[251] As the largest trading centre in East India, Kolkata has several high-circulation financial dailies, including The Economic Times, The Financial Express, Business Line and Business Standard.[251][252] Vernacular newspapers, such as those in the Hindi, Urdu, Gujarati, Odia, Punjabi and Chinese languages, are read by minorities.[251][107] Major periodicals based in Kolkata include Desh, Sananda, Saptahik Bartaman, Unish-Kuri, Anandalok and Anandamela.[251] Historically, Kolkata has been the centre of the Bengali little magazine movement.[253][254]

All India Radio, the national state-owned radio broadcaster, airs several AM radio stations in the city. Kolkata has 10 local radio stations broadcasting on FM, including three from AIR. India's state-owned television broadcaster, Doordarshan, provides two free-to-air terrestrial channels,[255] while a mix of Bengali, Hindi, English, and other regional channels are accessible via cable subscription, direct-broadcast satellite services, or internet-based television.[256][257][258] Bengali-language 24-hour television news channels include ABP Ananda, Tara Newz, Kolkata TV, 24 Ghanta and Kolkata TV.[259]

Sports

The most popular sports in Kolkata are football and cricket. Unlike most parts of India, the residents show significant passion for football.[260] The city is home to top national football clubs such as Mohun Bagan A.C., East Bengal F.C. and the Mohammedan Sporting Club.[261][262] Calcutta Football League, which was started in 1898, is the oldest football league in Asia.[263] Mohun Bagan A.C., one of the oldest football clubs in Asia, is the only organisation to be dubbed a "National Club of India".[264][265] Football matches between Mohun Bagan and East Bengal, dubbed as the Kolkata derby, witness large audience attendance and rivalry between patrons.[266] The multi-use Salt Lake Stadium, also known as Yuva Bharati Krirangan, is India's largest stadium by seating capacity. Most matches of the 2017 FIFA U-17 World Cup were played in the Salt Lake Stadium including both Semi-final matches and the Final match. Kolkata also accounted for 45% of total attendance in 2017 FIFA U-17 World Cup with an average of 55,345 spectators.[267] The Calcutta Cricket and Football Club is the second-oldest cricket club in the world.[268][269]

As in the rest of India, cricket is popular in Kolkata and is played on grounds and in streets throughout the city.[270][271] Kolkata has the Indian Premier League franchise Kolkata Knight Riders; the Cricket Association of Bengal, which regulates cricket in West Bengal, is also based in the city. Kolkata also has an Indian Super League franchise known as Atlético de Kolkata. Tournaments, especially those involving cricket, football, badminton and carrom, are regularly organised on an inter-locality or inter-club basis.[214] The Maidan, a vast field that serves as the city's largest park, hosts several minor football and cricket clubs and coaching institutes.[272] Eden Gardens, which has a capacity of 68,000 as of 2017,[273] hosted the final match of the 1987 Cricket World Cup. It is home to the Bengal cricket team and the Kolkata Knight Riders.

Kolkata's Netaji Indoor Stadium served as host of the 1981 Asian Basketball Championship, where India's national basketball team finished 5th, ahead of teams that belong to Asia's basketball elite, such as Iran. The city has three 18-hole golf courses. The oldest is at the Royal Calcutta Golf Club, the first golf club built outside the United Kingdom.[274][275] The other two are located at the Tollygunge Club and at Fort William. The Royal Calcutta Turf Club hosts horse racing and polo matches.[276] The Calcutta Polo Club is considered the oldest extant polo club in the world.[277][278][279] The Calcutta Racket Club is a squash and racquet club in Kolkata. It was founded in 1793, making it one of the oldest rackets clubs in the world, and the first in the Indian subcontinent.[280][281] The Calcutta South Club is a venue for national and international tennis tournaments; it held the first grass-court national championship in 1946.[282][283] In the period 2005–2007, Sunfeast Open, a tier-III tournament on the Women's Tennis Association circuit, was held in the Netaji Indoor Stadium; it has since been discontinued.[284][285]

The Calcutta Rowing Club hosts rowing heats and training events. Kolkata, considered the leading centre of rugby union in India, gives its name to the oldest international tournament in rugby union, the Calcutta Cup.[286][287][288] The Automobile Association of Eastern India, established in 1904,[289][290] and the Bengal Motor Sports Club are involved in promoting motor sports and car rallies in Kolkata and West Bengal.[291][292] The Beighton Cup, an event organised by the Bengal Hockey Association and first played in 1895, is India's oldest field hockey tournament; it is usually held on the Mohun Bagan Ground of the Maidan.[293][294] Athletes from Kolkata include Sourav Ganguly, Pankaj Roy and Jhulan Goswami, who are former captains of the Indian national cricket team; Olympic tennis bronze medalist Leander Paes, golfer Arjun Atwal, and former footballers Sailen Manna, Chuni Goswami, P. K. Banerjee and Subrata Bhattacharya.

Sister cities

References

-

- "India: Calcutta, the capital of culture-Telegraph". telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Kolkata remains cultural capital of India: Amitabh Bachchan – Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". 10 November 2012. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2016.|

- India, Press Trust of (14 November 2013). "Foundation of Kolkata Museum of Modern Art laid". business-standard.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- "Home | Chief Electoral Officer". ceowestbengal.nic.in.

- "Home | Chief Electoral Officer". ceowestbengal.nic.in.

- "Home | Chief Electoral Officer". ceowestbengal.nic.in.

- "AC-Wise Polling Stations – South 24 Parganas". s24pgs.gov.in.

- "web.archieve.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2013.

- "District Census Handbook – Kolkata" (PDF). Census of India. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner. p. 43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Basic Statistics of Kolkata". Kolkata Municipal Corporation. Kolkata Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- "Kolkata Municipal Corporation Demographics". Census of India. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "Urban agglomerations/cities having population 1 million and above" (PDF). Provisional population totals, census of India 2011. Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- "INDIA STATS: Million plus cities in India as per Census 2011". Press Information Bureau, Mumbai. National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

-

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 47th report (July 2008 to June 2010)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. pp. 122–126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Singh, Shiv Sahay (3 April 2012). "Official language status for Urdu in some West Bengal areas". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "Multi-lingual Bengal". The Telegraph. 11 December 2012. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

-

- "Global city GDP 2014". Brookings Institution. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- "Global city GDP rankings 2008–2025". PwC. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- "India's top 15 cities with the highest GDP Photos Yahoo! India Finance". Yahoo! Finance. 28 September 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "West Bengal Human Development Report 2004" (PDF).

- "Kolkata". Lexico. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Dutta, K.; Desai, A. (April 2008). Calcutta: a cultural history. Northampton, Massachusetts, US: Interlink Books. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-1-56656-721-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

-

- Banerjee, Partha Sarathi (5 February 2011), "Party, Power and Political Violence in West Bengal", Economic and Political Weekly, 46 (6): 16–18, ISSN 0012-9976, JSTOR 27918111

- Gooptu, Nandini (1 June 2007), "Economic Liberalisation, Work and Democracy: Industrial Decline and Urban Politics in Kolkata", Economic and Political Weekly, 42 (21): 1922–1933, JSTOR 4419634

- Jack, Ian (4 February 2011). "India's riptide of modern aspiration has not reached Kolkata – but that can't last". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Chakravorty, Sanjoy (2000). "From colonial city to global city? The far-from-complete spatial transformation of Calcutta". In Marcuse, Peter; Kempen, Ronald van (eds.). Globalizing cities: a new spatial order?. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 56–77. ISBN 978-0-631-21290-4.

- "Kalighat Kali Temple". kalighattemple.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- Chatterjee, S.N. (2008). Water resources, conservation and management. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 85. ISBN 978-81-269-0868-4. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Nair, P. Thankappan (1986). Calcutta in the 17th century. Kolkata: Firma KLM. pp. 54–58.

- Easwaran, Kenny. "The politics of name changes in India". Open Computing Facility, University of California at Berkeley. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A history of ancient and early medieval India: from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 395. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Das, S. (15 January 2003). "Pre-Raj crown on Clive House: abode of historical riches to be museum". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- Nair, P. Thankappan (1977). "A Portrait of Job Charnock". Job Charnock: The Founder of Calcutta: In Facts and Fiction: An Anthology. Calcutta: Engineering Times Publications. pp. 16–17. OCLC 4497022.

There are no two opinions that Calcutta is not the product of the vision of Job Charnock ... Charnock alone founded Calcutta.

- "Court changes Calcutta's history". BBC News. 16 May 2003. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- Gupta, Subhrangshu (18 May 2003). "Job Charnock not Kolkata founder: HC says city has no foundation day". The Tribune. Chandigarh, India. Archived from the original on 29 November 2006. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- Banerjee, Himadri; Gupta, Nilanjana; Mukherjee, Sipra, eds. (2009). Calcutta mosaic: essays and interviews on the minority communities of Calcutta. New Delhi: Anthem Press. ISBN 978-81-905835-5-8. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Mitter, Partha (June 1986). "The early British port cities of India: their planning and architecture circa 1640–1757". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 45 (2): 95–114. doi:10.2307/990090. JSTOR 990090.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunter, William Wilson (1886). The Indian Empire: its peoples, history, and products. London: Trübner & co. pp. 381–82. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Ahmed, Farooqui Salma; Farooqui, Salma Ahmed (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson Education India. p. 369. ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Arnold-Baker, Charles (30 July 2015). The Companion to British History. Taylor & Francis. p. 504. ISBN 978-1-317-40039-4. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018.

- Dutta, Krishna (2003). Calcutta: a cultural and literary history. Oxford, UK: Signal Books. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-902669-59-5. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Pati, Biswamoy (2006). "Narcotics and empire". The Hindu; Frontline. 23 (10). Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.IV, (1848) London, Charles Knight, p.35

- Hardgrave, Robert L. Jr (1990). "A portrait of Black Town: Balthazard Solvyns in Calcutta, 1791–1804". In Pal, Pratapaditya (ed.). Changing visions, lasting images: Calcutta through 300 years. Bombay: Marg Publications. pp. 31–46. ISBN 978-81-85026-11-4. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- Chaudhuri, NC (2001). The autobiography of an unknown Indian. New York: New York Review of Books. pp. v–xi. ISBN 978-0-940322-82-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stępień, Jakub; Tokarski, Stanisław; Latos, Tomasz; Jarecka-Stępień, Katarzyna (2011). "Indian way to independence. The Indian National Congress". Towards freedom. Ideas of "solidarity" in comparison with the thought of the Indian National Congress. Kraków, Poland: Wydawnictwo Stowarzyszenia "Projekt Orient". pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-83-933917-4-5.

- Chatterji, Joya (2007). The Spoils of Partition: Bengal and India, 1947–1967. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781139468305. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Wright, Tom (11 November 2011). "Why Delhi? The Move From Calcutta". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Hall, Peter (2002). Cities of tomorrow. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 198–206. ISBN 978-0-631-23252-0.

- Randhawa, K. (15 September 2005). "The bombing of Calcutta by the Japanese". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- "Pacific War timeline: New Zealanders in the Pacific War". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- Sen, A (1973). Poverty and famines. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 52–85. ISBN 978-0-19-828463-5.

- Burrows, Frederick (22 August 1946). A copy of a secret report written on 22 August 1946 to the Viceroy Lord Wavell, from Sir Frederick John Burrows, concerning the Calcutta riots (Report). The British Library. IOR: L/P&J/8/655 f.f. 95, 96–107. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Das, Suranjan (2000). "The 1992 Calcutta Riot in Historical Continuum: A Relapse into 'Communal Fury'?". Modern Asian Studies. 34 (2): 281–306. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0000336X. JSTOR 313064.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Suhrawardy, H. S. (1987). "Direct action day". In Talukdar, M. H. R. (ed.). Memoirs of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. Dhaka, Bangladesh: The University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-984-05-1087-0. Archived from the original on 14 March 2006.

- Gandhi, R (1992). Patel: a life. Ahmedabad, India: Navajivan. p. 497. ASIN B0006EYQ0A.

- Bennett, A; Hindle, J (1996). London review of books: an anthology. London: Verso Books. pp. 63–70. ISBN 978-1-85984-121-1.

- Follath, Erich (30 November 2005). "From poorhouse to powerhouse". Spiegel Online. Hamburg. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Biswas, S. (16 April 2006). "Calcutta's colorless campaign". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- Dutta, Krishna (2003). Calcutta: a cultural and literary history. Oxford, UK: Signal Books. pp. 185–87. ISBN 978-1-902669-59-5. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- Singh, Chandrika (1987). Communist and socialist movement in India: a critical account. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. pp. 154–55. ISBN 978-81-7099-031-4. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- Dutta, Tanya (22 March 2006). "Rising Kolkata's winners and losers". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- "PIA01844: space radar image of Calcutta, West Bengal, India". NASA. 15 April 1999. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- Chatterjee, S. N. (2008). Water Resources, Conservation and Management. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 33. ISBN 978-81-269-0868-4.

- Roy Chadhuri, S.; Thakur, A. R. (25 July 2006). "Microbial genetic resource mapping of East Calcutta wetlands". Current Science. 91 (2): 212–17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Das, Diptendra; Chattopadhyay, B. C. (17–19 December 2009). Characterization of soil over Kolkata municipal area (PDF). Indian Geotechnical Conference. 1. Guntur, India. pp. 11–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- Bunting, S. W.; Kundu, N.; Mukherjee, M. Situation analysis. Production systems and natural resources use in PU Kolkata (PDF) (Report). Stirling, UK: Institute of Aquaculture, University of Stirling. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- "Hazard profiles of Indian districts" (PDF). National Capacity Building Project in Disaster Management. UNDP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- "Introducing KMA" (PDF). Annual Report 2011. Kolkata Metropolitan Development Authority. 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- "007 Kolkata (India)" (PDF). World Association of the Major Metropolises. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- Sahdev, Shashi; Verma, Nilima, eds. (2008). Kolkata—an outline. Industry and Economic Planning. Town and Country Planning Organisation, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. Archived from the original (DOC) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calcutta, West Bengal, India (Map). Mission to planet earth program. NASA. 20 June 1996. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Kolkata heritage". Government of West Bengal. Retrieved 27 November 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "BSNL may take two weeks to be back online". Times of India. New Delhi. Times News Network (TNN). 9 July 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

With the Camac Street-Park Street-Shakespeare Sarani commercial hub located smack in the middle of the affected zone...

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Yardley, Jim (27 January 2011). "In city's teeming heart, a place to gaze and graze". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

To Kolkata, it is the 'lungs of the city,' a recharge zone for the soul.

- Das, Soumitra (21 February 2010). "Maidan marauders". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Retrieved 27 November 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chakraborti, Suman (2 November 2011). "Beautification project for Salt Lake, Sec V and New Town". Times of India. New Delhi. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "History of Sector V". Nabadiganta Industrial Township Authority. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Kolkata! India's new IT hub". Rediff.com. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- "Weatherbase entry for Kolkata". Canty and Associates LLC. Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- "kal Baisakhi". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 30 August 2006. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- Khichar, M. L.; Niwas, R. (14 July 2003). "Know your monsoon". The Tribune. Chandigarh, India. Archived from the original on 18 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "Calcutta: not 'the city of joy'". Gaia: Environmental Information System. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- Bilham, Roger (1994). "The 1737 Calcutta earthquake and cyclone evaluated" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 84 (5): 1650–57. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gastrell, James Eardley; Blanford, Henry Francis (1866). Report on the Calcutta cyclone of the 5th October 1864. Calcutta: O.T. Cutter, Military Orphan Press. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- "Station: Calcutta (Alipur) Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 161–162. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M237. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Table 3 Monthly mean duration of Sun Shine (hours) at different locations in India" (PDF). Daily Normals of Global & Diffuse Radiation (1971–2000). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Normals Data: Kolkata/Alipore - India Latitude: 22.53°N Longitude: 88.33°E Height: 6 (m)". Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Central Pollution Control Board. "Annual report 2008–2009" (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- "Smog city chokes & grounds: foul air, moist and smoky". The Telegraph. Kolkata. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- Bhaumik, Subir (17 May 2007). "Oxygen supplies for India police". BBC. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- "Genesis and growth of the Calcutta Stock Exchange". Calcutta Stock Exchange Association. Archived from the original on 19 April 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- "Better Integrated Transport Modes will Help Reinvent Kolkata". World Bank. 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Dutta, Sudipta (1 February 2009). "Calcutta chronicles". Financial Express. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Ganguly, Deepankar (30 November 2006). "Hawkers stay as Rs. 265 crore talks". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- Kundu, N. "Understanding slums: case studies for the global report on human settlements 2003. The case of Kolkata, India" (PDF). Development Planning Unit. University College, London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- "End is nigh for Gandhis after India's marathon poll". The Times. 12 January 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- M., Sonalee (16 March 2011). "Kolkata's retail story". The Daily Star. Dhaka, Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- George, Tunia Cherian (1 January 2006). "Hospitality sector gets a boost from buoyant economy". The Hindu Business Line. Chennai. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- Khanna, Rohit; Roy, Monalisa (12 January 2009). "Kolkata real estate players project 40% growth by April". Financial Express. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- Roy Chowdhury, Joy (October 2011). "Looking East". The Express Hospitality. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- "West Bengal industrial growth rate higher than national average". Economic Times. New Delhi. 1 December 2008. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- Decadal Variation In Population Since 1901

- "Calcuttan". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Prithvijit (14 November 2011). "Kolkatans relish a journey down familiar terrain". Times of India. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- "Area, population, decennial growth rate and density for 2001 and 2011 at a glance for West Bengal and the districts: provisional population totals paper 1 of 2011: West Bengal". Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- "Sex ratio, 0–6 age population, literates and literacy rate by sex for 2001 and 2011 at a glance for West Bengal and the districts: provisional population totals paper 1 of 2011: West Bengal". Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Dutta, Romita (5 April 2011). "Kolkata sees dip in population, suburbs register an increase". Mint. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.