Cardinal direction

The four cardinal directions, or cardinal points, are the directions north, east, south, and west, commonly denoted by their initials N, E, S, and W. East and west are perpendicular (at right angles) to north and south, with east being in the clockwise direction of rotation from north and west being directly opposite east. Points between the cardinal directions form the points of the compass.

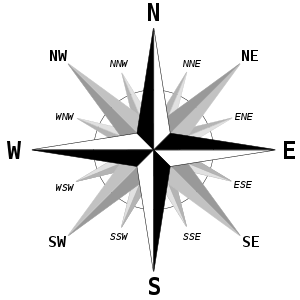

The intercardinal (also called the intermediate directions and, historically, ordinal) directions are northeast (NE), southeast (SE), southwest (SW), and northwest (NW). The intermediate direction of every set of intercardinal and cardinal direction is called a secondary intercardinal direction, the eight shortest points in the compass rose that is shown to the right (e.g. NNE, ENE, and ESE).

Locating the directions

Direction versus bearing

To keep to a bearing is not, in general, the same as going in a straight direction along a great circle. Conversely, one can keep to a great circle and the bearing may change. Thus the bearing of a straight path crossing the North Pole changes abruptly at the Pole from North to South. When travelling East or West, it is only on the Equator that one can keep East or West and be going straight (without the need to steer). Anywhere else, maintaining latitude requires a change in direction, requires steering. However, this change in direction becomes increasingly negligible as one moves to lower latitudes.

Magnetic compass

The Earth has a magnetic field which is approximately aligned with its axis of rotation. A magnetic compass is a device that uses this field to determine the cardinal directions. Magnetic compasses are widely used, but only moderately accurate. The north pole of the magnetic needle points towards the geographic north pole of the earth and vice versa. This is because the geographic north pole of the earth lies very close to the magnetic south pole of the earth. This south magnetic pole of the earth located at an angle of 17 degrees to the geographic north pole attracts the north pole of the magnetic needle and vice versa.

The Sun

The position of the Sun in the sky can be used for orientation if the general time of day is known. In the morning the Sun rises roughly in the east (due east only on the equinoxes) and tracks upwards. In the evening it sets in the west, again roughly and only due west exactly on the equinoxes. In the middle of the day, it is to the south for viewers in the Northern Hemisphere, who live north of the Tropic of Cancer, and the north for those in the Southern Hemisphere, who live south of the Tropic of Capricorn. This method does not work very well when closer to the equator (i.e. between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn) since, in the northern hemisphere, the sun may be directly overhead or even to the north in summer. Conversely, at low latitudes in the southern hemisphere the sun may be to the south of the observer in summer. In these locations, one needs first to determine whether the sun is moving from east to west through north or south by watching its movements—left to right means it is going through south while the right to left means it is going through north; or one can watch the sun's shadows. If they move clockwise, the sun will be in the south at midday, and if they move anticlockwise, then the sun will be in the north at midday.

Because of the Earth's axial tilt, no matter what the location of the viewer, there are only two days each year when the sun rises precisely due east. These days are the equinoxes. On all other days, depending on the time of year, the sun rises either north or south of true east (and sets north or south of true west). For all locations, the sun is seen to rise north of east (and set north of west) from the Northward equinox to the Southward equinox, and rise south of east (and set south of west) from the Southward equinox to the Northward equinox.

Watch dial

There is a traditional method by which an analogue watch can be used to locate north and south. The Sun appears to move in the sky over a 24-hour period while the hour hand of a 12-hour clock dial takes twelve hours to complete one rotation. In the northern hemisphere, if the watch is rotated so that the hour hand points toward the Sun, the point halfway between the hour hand and 12 o'clock will indicate south. For this method to work in the southern hemisphere, the 12 is pointed toward the Sun and the point halfway between the hour hand and 12 o'clock will indicate north. During daylight saving time, the same method can be employed using 1 o'clock instead of 12. The difference between local time and zone time, the equation of time, and (near the tropics) the non-uniform change of the Sun's azimuth at different times of day limit the accuracy of this method.

Sundial

A portable sundial can be used as a more accurate instrument than a watch for determining the cardinal directions. Since the design of a sundial takes account of the latitude of the observer, it can be used at any latitude. See: Sundial#Using a sundial as a compass.

Astronomy

Astronomy provides a method for finding direction at night. All the stars appear to lie on the imaginary Celestial sphere. Because of the rotation of the Earth, the Celestial Sphere appears to rotate around an axis passing through the North and South poles of the Earth. This axis intersects the Celestial Sphere at the North and South Celestial poles, which appear to the observer to lie directly above due North and South respectively on the horizon.

In either hemisphere, observations of the night sky show that the visible stars appear to be moving in circular paths, caused by the rotation of the Earth. This is best seen in a long exposure photograph, which is obtained by locking the shutter open for most of the intensely dark part of a moonless night. The resulting photograph reveals a multitude of concentric arcs (portions of perfect circles) from which the exact center can be readily derived, and which corresponds to the Celestial pole, which lies directly above the position of the true pole (North or South) on the horizon. A published photograph exposed for nearly 8 hours demonstrates this effect.

The Northern Celestial pole is currently (but not permanently) within a fraction of 1 degree of the bright star Polaris. The exact position of the pole changes over thousands of years because of the precession of the equinoxes. Polaris is also known as the North Star, and is generically called a pole star or lodestar. Polaris is only visible during fair weather at night to inhabitants of the Northern Hemisphere. The asterism "Big Dipper" may be used to find Polaris. The 2 corner stars of the "pan" (those opposite from the handle) point above the top of the "pan" to Polaris.

While observers in the Northern hemisphere can use the star Polaris to determine the Northern celestial pole, the Octans constellation's South Star is hardly visible enough to use for navigation. For this reason, the preferred alternative is to use the constellation Crux (The Southern Cross). The southern celestial pole lies at the intersection of (a) the line along the long axis of crux (i.e. through Alpha Crucis and Gamma Crucis) and (b) a line perpendicularly bisecting the line joining the "Pointers" (Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri).

Gyrocompass

At the very end of the 19th century, in response to the development of battleships with large traversable guns that affected magnetic compasses, and possibly to avoid the need to wait for fair weather at night to precisely verify one's alignment with true north, the gyrocompass was developed for shipboard use. Since it finds true, rather than magnetic, north, it is immune to interference by local or shipboard magnetic fields. Its major disadvantage is that it depends on technology that many individuals might find too expensive to justify outside the context of a large commercial or military operation. It also requires a continuous power supply for its motors, and that it can be allowed to sit in one location for a period of time while it properly aligns itself.

Satellite navigation

Near the end of the 20th century, the advent of satellite-based Global Positioning Systems (GPS) provided yet another means for any individual to determine true north accurately. While GPS Receivers (GPSRs) function best with a clear view of the entire sky, they function day or night, and in all but the most severe weather. The government agencies responsible for the satellites continuously monitor and adjust them to maintain their accurate alignment with the Earth. There are consumer versions of the receivers that are attractively priced. Since there are no periodic access fees, or other licensing charges, they have become widely used. GPSR functionality is becoming more commonly added to other consumer devices such as mobile phones. Handheld GPSRs have modest power requirements, can be shut down as needed, and recalibrate within a couple of minutes of being restarted. In contrast with the gyrocompass which is most accurate when stationary, the GPS receiver, if it has only one antenna, must be moving, typically at more than 0.1 mph (0.2 km/h), to correctly display compass directions. On ships and aircraft, GPS receivers are often equipped with two or more antennas, separately attached to the vehicle. The exact latitudes and longitudes of the antennas are determined, which allows the cardinal directions to be calculated relative to the structure of the vehicle. Within these limitations GPSRs are considered both accurate and reliable. The GPSR has thus become the fastest and most convenient way to obtain a verifiable alignment with the cardinal directions.

Additional points

Cardinal points (in degrees)

The directional names are routinely associated with the degrees of rotation in the unit circle, a necessary step for navigational calculations (derived from trigonometry) and/or for use with Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) receivers. The four cardinal directions correspond to the following degrees of a compass:

- North (N): 0° = 360°

- East (E): 90°

- South (S): 180°

- West (W): 270°

Intercardinal directions

The intercardinal (intermediate, or, historically, ordinal[1]) directions are the four intermediate compass directions located halfway between each pair of cardinal directions.

- Northeast (NE), 45°, halfway between north and east, is the opposite of southwest.

- Southeast (SE), 135°, halfway between south and east, is the opposite of northwest.

- Southwest (SW), 225°, halfway between south and west, is the opposite of northeast.

- Northwest (NW), 315°, halfway between north and west, is the opposite of southeast.

Other

These eight directional names have been further compounded, resulting in a total of 32 named points evenly spaced around the compass: north (N), north by east (NbE), north-northeast (NNE), northeast by north (NEbN), northeast (NE), northeast by east (NEbE), east-northeast (ENE), east by north (EbN), east (E), etc.

Usefulness of cardinal points

With the cardinal points thus accurately defined, by convention cartographers draw standard maps with north (N) at the top, and east (E) at the right. In turn, maps provide a systematic means to record where places are, and cardinal directions are the foundation of a structure for telling someone how to find those places.

North does not have to be at the top. Most maps in medieval Europe, for example, placed east (E) at the top.[2] A few cartographers prefer south-up maps. Many portable GPS-based navigation computers today can be set to display maps either conventionally (N always up, E always right) or with the current instantaneous direction of travel, called the heading, always up (and whatever direction is +90° from that to the right).

Beyond geography

In mathematics, cardinal directions or cardinal points are the six principal directions or points along the x-, y- and z-axis of three-dimensional space.

In the real world there are six cardinal directions not involved with geography that are north, south, east, west, up and down. In this context, up and down relate to elevation, altitude, or possibly depth (if water is involved). The topographic map is a special case of cartography in which the elevation is indicated on the map, typically via contour lines.

In astronomy, the cardinal points of an astronomical body as seen in the sky are four points defined by the directions towards which the celestial poles lie relative to the center of the disk of the object in the sky.[3][4] A line (here it is a great circle on the celestial sphere) from the center of the disk to the North celestial pole will intersect the edge of the body (the "limb") at the North point. The North point will then be the point on the limb that is closest to the North celestial pole. Similarly, a line from the center to the South celestial pole will define the South point by its intersection with the limb. The points at right angles to the North and South points are the East and West points. Going around the disk clockwise from the North point, one encounters in order the West point, the South point, and then the East point. This is opposite to the order on a terrestrial map because one is looking up instead of down.

Similarly, when describing the location of one astronomical object relative to another, "north" means closer to the North celestial pole, "east" means at a higher right ascension, "south" means closer to the South celestial pole, and "west" means at a lower right ascension. If one is looking at two stars that are below the North Star, for example, the one that is "east" will actually be further to the left.

Germanic origin of names

During the Migration Period, the Germanic languages' names for the cardinal directions entered the Romance languages, where they replaced the Latin names borealis (or septentrionalis) with north, australis (or meridionalis) with south, occidentalis with west and orientalis with east. It is possible that some northern people used the Germanic names for the intermediate directions. Medieval Scandinavian orientation would thus have involved a 45 degree rotation of cardinal directions.[5]

- north (Proto-Germanic *norþ-) from the proto-Indo-European *nórto-s 'submerged' from the root *ner- 'left, below, to the left of the rising sun' whence comes the Ancient Greek name Nereus.[6]

- east (*aus-t-) from the word for dawn. The proto-Indo-European form is *austo-s from the root *aues- 'shine (red)'.[7] See Ēostre.

- south (*sunþ-), derived from proto-Indo-European *sú-n-to-s from the root *seu- 'seethe, boil'.[8] Cognate with this root is the word Sun, thus "the region of the Sun".

- west (*wes-t-) from a word for "evening". The proto-Indo-European form is *uestos from the root *ues- 'shine (red)',[9] itself a form of *aues-.[10] Cognate with the root are the Latin words vesper and vesta and the Ancient Greek Hestia, Hesperus and Hesperides.

Cultural variations

In many regions of the world, prevalent winds change direction seasonally, and consequently many cultures associate specific named winds with cardinal and intercardinal directions. For example, classical Greek culture characterized these winds as Anemoi.

In pre-modern Europe more generally, between eight and 32 points of the compass – cardinal and intercardinal subdirections – were given names. These often corresponded to the directional winds of the Mediterranean Sea (for example, southeast was linked to the Sirocco, a wind from the Sahara).

Particular colors are associated in some traditions with the cardinal points. These are typically "natural colors" of human perception rather than optical primary colors.

Many cultures, especially in Asia, include the center as a fifth cardinal point.

Northern Eurasia

| Northern Eurasia | N | E | S | W | C | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slavic | — | [11] | ||||

| China | [12][13] | |||||

| Ainu | [14][15] | |||||

| Turkic | [14] | |||||

| Kalmyks | — | [16] | ||||

| Tibet | [14] |

Central Asian, Eastern European and North East Asian cultures frequently have traditions associating colors with four or five cardinal points.

Systems with five cardinal points include those from pre-modern China, as well as traditional Turkic, Tibetan and Ainu cultures.

In Chinese tradition, a five cardinal point system is a foundation for I Ching, the Wu Xing and the five naked-eye planets. In traditional Chinese astrology, the zodiacal belt is divided into the four constellation groups corresponding to the four cardinal directions.

Each direction is often identified with a color, and (at least in China) with a mythological creature of that color. Geographical or ethnic terms may contain the name of the color instead of the name of the corresponding direction.[12][13]

Examples

East: Green (青 "qīng" corresponds to both green and blue); Spring; Wood

- Qingdao (Tsingtao) "Green Island": a city on the east coast of China

- Green Ukraine

- Red River (Asia): south of China

- Red Ruthenia

- Red Jews: a semi-mythological group of Jews

- Red Croatia

- Red Sea

West: White; Autumn; Metal

- White Sheep Turkmen

- Akdeniz, meaning White Sea: Mediterranean Sea in Turkish

- Balts, Baltic words containing the stem balt-, "white"

- White Ruthenia

- White Croatia

- Heilongjiang "Black Dragon River" province in Northeast China, also the Amur River

- Kara-Khitan Khanate "Black Khitans" who originated in Northern China

- Black Hungarians

- Black Ruthenia

- Huangshan: "Yellow Mountain" in central China

- Huang He: "Yellow River" in central China

- Golden Horde: "Central Army" of the Mongols

Arabic world

Countries where Arabic is used refer to the cardinal directions as Ash Shamal (N), Al Gharb (W), Ash Sharq (E) and Al Janoob (S). Additionally, Al Wusta is used for the center. All five are used for geographic subdivision names (wilayahs, states, regions, governorates, provinces, districts or even towns), and some are the origin of some Southern Iberian place names (such as Algarve, Portugal and Axarquía, Spain).

Native Americans

In Mesoamerica and North America, a number of traditional indigenous cosmologies include four cardinal directions and a center. Some may also include "above" and "below" as directions, and therefore focus on a cosmology of seven directions. Each direction may be associated with a color, which can vary widely between nations, but which is usually one of the basic colors found in nature and natural pigments, such as black, red, white, and yellow, with occasional appearances of blue, green, or other hues.[17] In some cases, e.g., many of the Puebloan peoples of the Southwestern United States, the four named directions are not North, South, East and West but are the four intermediate directions associated with the places of sunrise and sunset at the winter and summer solstices.[18][19] There can be great variety in color symbolism, even among cultures that are close neighbors geographically.

India

Ten Hindu deities, known as the "Dikpālas", have been recognized in classical Indian scriptures, symbolizing the four cardinal and four intercardinal directions with the additional directions of up and down. Each of the ten directions has its own name in Sanskrit.[20]

Indigenous Australia

Some indigenous Australians have cardinal directions deeply embedded in their culture. For example, the Warlpiri people have a cultural philosophy deeply connected to the four cardinal directions[21] and the Guugu Yimithirr people use cardinal directions rather than relative direction even when indicating the position of an object close to their body. (For more information, see: Cultural use of cardinal rather than relative direction.)

The precise direction of the cardinal points appears to be important in Aboriginal stone arrangements.

Many aboriginal languages contain words for the usual four cardinal directions, but some contain words for 5 or even 6 cardinal directions.[22]

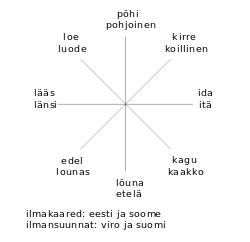

Unique (non-compound) names of intercardinal directions

In some languages, such as Estonian, Finnish and Breton, the intercardinal directions have names that are not compounds of the names of the cardinal directions (as, for instance, northeast is compounded from north and east). In Estonian, those are kirre (northeast), kagu (southeast), edel (southwest), and loe (northwest), in Finnish koillinen (northeast), kaakko (southeast), lounas (southwest), and luode (northwest). In Japanese, there is the interesting situation that native Japanese words (yamato kotoba, kun readings of kanji) are used for the cardinal directions (such as minami for 南, south), but borrowed Chinese words (on readings of kanji) are used for intercardinal directions (such as tō-nan for 東南, southeast, lit. "east-south"). In the Malay language, adding laut (sea) to either east (timur) or west (barat) results in northeast or northwest, respectively, whereas adding daya to west (giving barat daya) results in southwest. However, southeast has a special word: tenggara.

Sanskrit and other Indian languages that borrow from it use the names of the gods associated with each direction: east (Indra), southeast (Agni), south (Yama/Dharma), southwest (Nirrti), west (Varuna), northwest (Vayu), north (Kubera/Heaven) and northeast (Ishana/Shiva). North is associated with the Himalayas and heaven while the south is associated with the underworld or land of the fathers (Pitr loka). The directions are named by adding "disha" to the names of each god or entity: e.g. Indradisha (direction of Indra) or Pitrdisha (direction of the forefathers i.e. south).

The Hopi language and the Tewa dialect spoken by the Arizona Tewa have proper names for the solstitial directions, which are approximately intercardinal, rather than for the cardinal directions.[23][24]

Non-compass directional systems

Use of the compass directions is common and deeply embedded in European culture, and also in Chinese culture (see south-pointing chariot). Some other cultures make greater use of other referents, such as towards the sea or towards the mountains (Hawaii, Bali), or upstream and downstream (most notably in ancient Egypt, also in the Yurok and Karuk languages). Lengo (Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands) has four non-compass directions: landward, seaward, upcoast, and downcoast.

See also

- Azimuth

- Classical compass winds – an early source of cardinal directions

- Cultural synesthesia

- Elevation – the mapping information ignored by the cardinal point system

- Geocaching – an international hobby

- Geographic Information System (GIS)

- Latitude and Longitude

- List of cartographers – famous map makers through history

- List of international common standards

- Magnetic deviation – explanation of the slight misalignment of a compass with the Earth's north and south poles

- Orienteering – an international hobby/sport that depends on knowledge of cardinal directions and how to locate them

- Relative direction

- Uses of trigonometry

References

- ""Ordinal directions refer to the direction found at the point equally between each cardinal direction," Cardinal Directions and Ordinal Directions, geolounge.com". Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Snyder's Medieval Art, 2nd ed. (ed. Luttikhuizen and Verkerk; Prentice Hall, 2006), pp. 226-7.

- Rigge, W. F. "Partial eclipse of the moon, 1918, June 24". Popular Astronomy. 26: 373. Bibcode:1918PA.....26..373R.

rigge1918

- Meadows, Peter; meadows. "Solar Observing: Parallactic Angle". Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- See e.g. Weibull, Lauritz. De gamle nordbornas väderstrecksbegrepp. Scandia 1/1928; Ekblom, R. Alfred the Great as Geographer. Studia Neophilologica 14/1941-2; Ekblom, R. Den forntida nordiska orientering och Wulfstans resa till Truso. Förnvännen. 33/1938; Sköld, Tryggve. Isländska väderstreck. Scripta Islandica. Isländska sällskapets årsbok 16/1965.

- entries 765-66 of the Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

- entries 86-7 of the Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

- entries 914-15 of the Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

- entries 1173 of the Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

- entries 86-7 of the Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch

- Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedic dictionary, Kiev, 1987.

- "Cardinal colors in Chinese tradition". Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- "Chinese Cosmogony". Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- "Colors of the Four Directions". Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

-

"Two Studies of Color". JSTOR 1264798.

In Ainu... siwnin means both 'yellow' and 'blue' and hu means 'green' and 'red'

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Krupp, E. C.: "Beyond the Blue Horizon: Myths and Legends of the Sun, Moon, Stars, and Planets", page 371. Oxford University Press, 1992

- Anderson, Kasper Wrem; Helmke, Christophe (2013), "The Personifications of Celestial Water: The Many Guises of the Storm God in the Pantheon and Cosmology of Teotihuacan", Contributions in New World Archaeology, 5: 165–196, at pp. 177-179.

- McCluskey, Stephen C. (2014), "Hopi and Puebloan Ethnoastronomy and Ethnoscience", in Ruggles, Clive L. N. (ed.), Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, New York: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 649–658, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_48, ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1

- Curtis, Edward S. (1922), Hodge, Frederick Webb (ed.), The Hopi, The North American Indian, 12, Norwood, Mass.: The Plimpton Press, p. 246, archived from the original on 22 December 2015, retrieved 23 August 2014,

Hopi orientation corresponds only approximately with ours, their cardinal points being marked by the solstitial rising and setting points of the sun.... Their cardinal points therefore are not mutually equidistant on the horizon and agree roughly with our semi-cardinal points.

- H. Rodrigues (22 April 2016). "The Dikpalas". www.mahavidya.ca. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- Ngurra-kurlu: A way of working with Warlpiri people Pawu-Kurlpurlurnu WJ, Holmes M and Box L. 2008, Desert Knowledge CRC Report 41, Alice Springs

- Orientations of linear stone arrangements in New South Wales Hamacher et al., 2013, Australian Archaeology, 75, 46-54 Archived 17 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Stephen, Alexander MacGregor (1936), Parsons, Elsie Clews (ed.), Hopi Journal of Alexander M. Stephen, Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, 23, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1190–1191, OCLC 716671864

- Malotki, Ekkehart (1979), Hopi-Raum: Eine sprachwissenschaftliche Analyse der Raumvorstellungen in der Hopi-Sprache, Tübinger Beiträge zur Linguistik (in German), 81, Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, p. 165, ISBN 3-87808-081-6