Constitutionalist Revolution

The Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932 (sometimes also referred to as Paulista War or Brazilian Civil War[1]) is the name given to the uprising of the population of the Brazilian state of São Paulo against the [[Brazilian Revolution of 1930 when Getúlio Vargas assumed the nation's Presidency; Vargas was supported by the people, the military and the political elites of Minas Gerais, Rio Grande do Sul and Paraíba. The movement grew out of local resentment from the fact that Vargas ruled by decree, unbound by a Constitution, in a provisional government. The 1930 also affected São Paulo by eroding the autonomy that states enjoyed during the term of the 1891 Constitution and preventing the inauguration of the governor of São Paulo Júlio Prestes in the Presidency of the Republic, while simultaneously overthrowing President Washington Luís, who was governor of São Paulo from 1920 to 1924. These events marked the end of the First Republic. Vargas appointed a northeasterner as governor of São Paulo.

| Constitutionalist Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Revolutionary troops entrenched in the battlefield. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

40,000 soldiers (military police and volunteers) 30 Armored Vehicles 44 artillery 9-10 aircraft |

100,000 soldiers (Army, Navy and Police) 90 Armored Vehicles 250 artillery 58 aircraft 4 Warships (Naval blockade of the Port of Santos) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,500 estimated dead |

1,050 estimated dead 3,800 wounded | ||||||

The Revolution's main goal was to press the provisional government headed by Getúlio Vargas to adopt and then abide by a new Constitution, since the elected President Prestes was kept from taking office. However, as the movement developed and resentment against President Vargas and his revolutionary government grew deeper, it came to advocate the overthrow of the Federal Government, and it was even speculated that one of the Revolutionaries' goals was the secession of São Paulo from the Brazilian federation. However, it is noted that the separatist scenario was used as a guerrilla tactic by the Federal Government to turn the population of the rest of the country against the state of São Paulo, broadcasting the alleged separatist notion throughout the country. There is no evidence that the movement's commanders sought separatism.

The uprising commenced on 9 July 1932, after four protesting students were killed by government troops on 23 May 1932. On the wake of their deaths, a movement called MMDC (from the initials of the names of each of the four students killed, Martins, Miragaia, Dráusio and Camargo) started. A fifth victim, Alvarenga, was also shot that night, but died months later.

In a few months, the state of São Paulo rebelled against the federal government. Counting on the solidarity of the political elites of two other powerful states, (Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Sul), the politicians from São Paulo expected a quick war. However, that solidarity was never translated into actual support, and the São Paulo revolt was militarily crushed on October 2, 1932. In total, there were 87 days of fighting (July 9 to October 4, 1932—with the last two days after the surrender of São Paulo), with a balance of 934 official deaths, though non-official estimates report up to 2,200 dead, and many cities in the state of São Paulo suffered damage due to fighting.

In spite of its military defeat, some of the movement's main demands were finally granted by Vargas afterwards: the appointment of a non-military state Governor, the election of a Constituent Assembly and, finally, the enactment of a new Constitution in 1934. However that Constitution was short-lived, as in 1937, amidst growing extremism on the left and right wings of the political spectrum, Vargas closed the National Congress and enacted another Constitution, which established an regime called Estado Novo.

July 9 marks the beginning of the Revolution of 1932, and is a holiday and the most important civic date of the state of São Paulo. The paulistas (as the inhabitants of São Paulo are known) consider the Revolution of 1932 as the greatest movement of its civic history. It was the first major revolt against the government of Getúlio Vargas and the last major armed conflict occurring in the history of Brazil.

The Paulistas and Federal Forces

According to García de Gabiola, when the revolution began the Paulistas only swayed 1 of the 8 divisions of the Brazilian Federal Army (the 2nd one, based in São Paulo), and with half of the Mixed Brigade based in the southern part of Mato Grosso. These forces were reinforced by the Força Publica Paulista, a regional military police, and the MMDC militias. In all, there were some 11-15,000 men at the beginning of the conflict, later joined by thousands of volunteers.[2] In fact, according to most authors, as Hilton, São Paulo equipped some 40 battalions made from volunteers, but García de Gabiola states that he has identified even up to 80 of them, of some 300 men each.[3] At the end, taking into account that in the São Paulo state armory's there were only between 15,000 and 29,000 rifles depending on the source, the Paulists were never able to arm more than 35,000 men maximum.[4] Additionally, the Paulists only had 6 million cartridges, failing their attempts to acquire some additional 500 millions, so, for an army of some 30,000 men fighting during 3 months, it represented a mere 4.4 cartridges per day per soldier.[5] Against them Brazil equipped approximately 100,000 men, but taking into account that a third of this amount never went to the front (they were kept to protect the rearguards and for security purposes in the other States), their numerical superiority was of some 2 to 1.[6]

Course of the Conflict

The main front was initially the eastern Paraiba Valley that led to Rio de Janeiro, the then-capital of Brazil. The 2nd Division, revolted, advanced against Rio, but was stopped dead by the loyal 1st Division based there under General Gois Monteiro, on the frontier between Rio and São Paulo. According to sources as Hilton,[7] General Tasso Fragoso, the chief of staff of the Brazilian Army, tried to oppose the deployment to the 1st Division in the Valley, for being friendly to the revolts, but according to García de Gabiola[8] he was likely just trying to protect the government based in Rio City in case of a similar revolt happening there. In any case Gois finally imposed over Tasso and the 1st Division was placed there just in time to block the Paulista advance. In the Paraíba, Gois Monteiro created the East Detachment, reaching some 34,000 men, against some 20,000 Paulistas, but after 3 months of trench warfare and despite advancing some 70 km, the Federals were still some 150 km distance to São Paulo City when the war ended.[9] In the South of São Paulo State, the Federals created the South Detachment, made of the Federal 3rd and 5th Divisions, 3 Cavalry divisions and the Gaucho Brigade of Rio Grande do Sul reaching 18,000 men against just 3-5,000 Paulistas depending on the date. The Federals broke the front in Itararé on July the 17th, producing the largest advance in the war, but they were still very far from São Paulo when the war ended.[10] Finally, the decisive front was the Minas Gerais Front, that was only active since August the 2nd. The 4th Federal Division based there, with the Police of Minais Gerais and other States troops, broke the front in Eleutério in the 26th of August, advancing some 50 km to near Campinas, adding 18,000 soldiers against some 7,000 Paulistas. In any case, there were just some 70 km to São Paulo City, so finally the Paulistas surrendered in October the 2nd to General Valdomiro Lima, uncle Getulio's Wife, Darcy Sarmanho Vargas.[11]

Naval Task Force and naval blockade of São Paulo

In the naval theater of conflict the Brazilian Navy has designated a naval task force to block the main port of the State of São Paulo, Port of Santos, aiming to cut the only supply line of the rebels by sea.

On July 10 the destroyer Mato Grosso (CT-10) left the port of Rio de Janeiro, and the next day, cruiser Rio Grande do Sul escorted by two destroyers Pará (CT-2) and Sergipe (CT-7) also left. To support the mission, the Naval Aviation sent three Savoia-Marchetti S-55A (numbers 1, 4 and 8) and two Martim PM (numbers 111 and 112). These five planes left Galeao on 12 July. All were provisionally based at the coves of the Island of San Sebastian, near the village of Bela village (current Ilha Bela). The Navy also intended to send some Vought Corsair O2U-2A for Vila Bela, but the Naval Aviation did not trust them to operate as floatplanes from the coves of the island. so it decided to expand the small airstrip next to the village so that they could operate with landing gear.

Aviation in the 1932 Constitutionalist War

Aviation played a role in the 1932 Revolution, although both sides had few aircraft. The federal government had approximately 58 aircraft divided between the Navy and the Army, as the Air Force at this time did not constitute an independent arm.

In contrast, the Paulistas had only two Potez 25 planes and two Waco CSO, plus a small number of private aircraft. In late July, the rebel government acquired another device, brought by Lieutenant Artur Mota Lima, who deserted the field of Afonsos, in Rio de Janeiro. The "vermelhinhos" as the aircraft of the federal government were known, not only acted in the front lines, but also were used to bomb several cities in São Paulo, including Campinas, which caused major damage. They served also as a propaganda weapon, dropping leaflets on enemy cities and local concentration of rebel troops. Already the aircraft of Units Constitutionalists Airlines (UAC) known as "hawks plume", little could do.

Still, they performed two feats of great impact: on 21 September, in a surprise attack to Moji-Mirim (already in power Eurico Dutra), managed to disable five of the seven federal aircraft stationed there before they could take off; on the 24th, three rebels Curtiss Falcon attacked the Brazilian cruiser Rio Grande do Sul, at anchor in Santos, in order to relax the blockade to the local port. In this attack one of the aircraft exploded in the air, killing the pilot and co-pilot. The other two devices, however, managed to accomplish the mission. Two months earlier, on July 23, Santos Dumont, the "Father of Aviation", depressed by the use of his invention as a weapon of war, committed suicide in Guaruja.

At the beginning of hostilities, legalistic Aviation was better served by aerial means. Military Aviation were mobilized: the Joint Aviation Group, with twelve aircraft Potez 25 TOE observation and bombing and five aircraft armed Waco CSO with machine guns and bombs door; the Military Aviation School, with a bomber Amiot 122 a Nieuport-Delage Ni-D 72 and eleven De Havilland DH 60T Moth trainers, updated in connection missions, observation and adjustment of artillery fire.

The Naval Aviation mobilized the 18th Division Note with four aircraft Vought O2U Corsair and the Flotilla Joint Patrol Aircraft Independent three planes Martin PM and seven Savoia-Marchetti S.55. To link tasks, reconnaissance and observation, was also available twelve De Havilland DH 60, two Avro 504.

If the first step was to mobilize existing resources, the second, both loyalists as Constitutionalists, was acquiring complementary means necessarily imported, since the local industry was unable to produce them. Contracts negotiated by the federal government, only one, on the purchase of thirty-six Waco C90, materialized quickly enough to allow for operational use in the conflict. Of the thirty-six, only ten were mounted in time to have effective participation still with particularity. The intention was to use C90 Waco primarily as fighter aircraft, and secondarily as bombing and observation. The contract specified the installation 7mm machine guns, with the purpose of using ammunition ever made in the country for weapons of the same caliber used in the infantry. However, because air munitions and land have distinct characteristics, the machine guns of Waco C90, often jam after the first bursts. The aircraft then went to meet primarily bombing and observation missions, and the few whose guns accepted the autochthonous ammunition were intensely ordered and commuted to the three fronts, primarily performing fighter missions.

.jpg)

For the rebels, difficulties in material procurement were significantly higher. The negotiations in New York City, for example, with Consolidated Aircraft for the purchase of ten aircraft Fleet 10D, when nearly completed, were aborted by direct intervention of the Brazilian government with the Department of State.

Only even through triangular operation in Buenos Aires in order to circumvent provisions of the Havana Treaty, it was possible to acquire ten aircraft (only 4 arrived in rebel aviation) Curtiss Falcon in the assembly plant of the Curtiss-Wright Corporation in Los Cerrillos, Chile, the amount of US$292,500. Were robust aircraft equipped with engine Curtiss D-12 435 H. P., top speed of 224 km / h, action radius of 1,000 km and a ceiling of 4,600 m, capable of carrying out bombing attacks. Without a doubt, were the most improved aircraft that participated in the air battle.[12]

In popular culture

The Revolution plays a key role in the setting of Peter Fleming's book Brazilian Adventure, an offbeat portrayal by a foreigner caught in the midst of the fighting.

Gallery

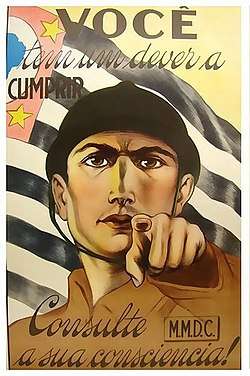

Constitutionalist Revolution recruiting poster, showing a Bandeirante with dictator Getúlio Vargas, in his hand.

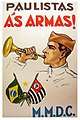

Constitutionalist Revolution recruiting poster, showing a Bandeirante with dictator Getúlio Vargas, in his hand. Paulista propaganda poster showing the flag of Brazil and São Paulo.

Paulista propaganda poster showing the flag of Brazil and São Paulo. Convocation poster for Paulista volunteer nurses.

Convocation poster for Paulista volunteer nurses. Rebel troops.

Rebel troops. Paulista cavalry volunteer.

Paulista cavalry volunteer. The teacher Maria Sguassábia volunteered in the trenches of São Paulo in 1932.

The teacher Maria Sguassábia volunteered in the trenches of São Paulo in 1932. Brazilian loyalist troops, September 1932.

Brazilian loyalist troops, September 1932. Soldiers from São Paulo photographed by Claro Jansson in Itararé.

Soldiers from São Paulo photographed by Claro Jansson in Itararé. Armored tractor called "FS-6" during the Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932.

Armored tractor called "FS-6" during the Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932. Train legalistic rebels taking prisoners.

Train legalistic rebels taking prisoners.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constitutionalist Revolution of 1932. |

- Revolutions of Brazil

- Paulista Revolt of 1924

Bibliography

Silva, Herculano. A Revolução Constitucionalista. Rio de Janeiro. Civilização Brasileira Editora. 1932.

García de Gabiola, Javier. 1932 São Paulo en Armas. Historia y Vida 535. October 2012. Barcelona. Prisma Editorial. Planeta.

Hilton, Stanley. A Guerra Civil Brasileira (The Brazilian Civil War). Rio de Janeiro. Nova Fronteira, 1982.

References

- Hilton, Stanley (1982). A Guerra Civil Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira.

- For the units involved see García de Gabiola. For the strength of the units see both Hilton and Garcia de Gabiola

- See Hilton and García de Gabiola

- See both Hilton and García de Gabiola.

- See both Hilton and García de Gabiola. The calculation of the 4.4 cartridges has been made by Garcia de Gabiola

- See García de Gabiola

- Stanley Hilton. A Guerra Civil Brasileira. Río de Janeiro. Nova Fronteira, 1982.

- Javier García de Gabiola. 1932, Sao Paulo en Armas. Historia y Vida 535. 2012

- See both Hilton and García de Gabiola for troop strength, Silva for details of the operations, and Garcia de Gabiola for a summary of them

- See both Hilton and García de Gabiola for troops strength, Silva for details of the operations, and Garcia de Gabiola for a summary of them and for military units

- See both Hilton and García de Gabiola for troops strength for the gen. Waldomiro Lima, uncle of the Getulio's wife, Darcy, Silva for details of the operations, and Garcia de Gabiola for a summary of them and for military units

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)