Mário de Andrade

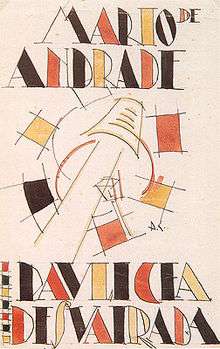

Mário Raul de Morais Andrade (October 9, 1893 – February 25, 1945) was a Brazilian poet, novelist, musicologist, art historian and critic, and photographer. One of the founders of Brazilian modernism, he virtually created modern Brazilian poetry with the publication of his Paulicéia Desvairada (Hallucinated City) in 1922. He has had an enormous influence on modern Brazilian literature, and as a scholar and essayist—he was a pioneer of the field of ethnomusicology—his influence has reached far beyond Brazil.[1]

Mário de Andrade | |

|---|---|

Mário de Andrade at age 35, 1928 | |

| Born | Mário Raul de Morais Andrade October 9, 1893 São Paulo, Brazil |

| Died | February 25, 1945 (aged 51) São Paulo, Brazil |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, musicologist, art historian, critic and photographer |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | Macunaíma |

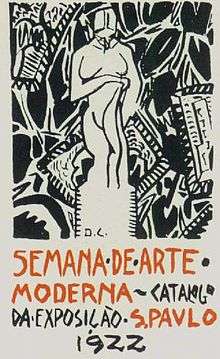

Andrade was the central figure in the avant-garde movement of São Paulo for twenty years.[2] Trained as a musician and best known as a poet and novelist, Andrade was personally involved in virtually every discipline that was connected with São Paulo modernism, and became Brazil's national polymath. His photography and essays on a wide variety of subjects, from history to literature and music, were widely published. He was the driving force behind the Week of Modern Art, the 1922 event that reshaped both literature and the visual arts in Brazil, and a member of the avant-garde "Group of Five." The ideas behind the Week were further explored in the preface to his poetry collection Pauliceia Desvairada, and in the poems themselves.

After working as a music professor and newspaper columnist he published his great novel, Macunaíma, in 1928. Work on Brazilian folk music, poetry, and other concerns followed unevenly, often interrupted by Andrade's shifting relationship with the Brazilian government. At the end of his life, he became the founding director of São Paulo's Department of Culture, formalizing a role he had long held as the catalyst of the city's—and the nation's—entry into artistic modernity.

Early life

Andrade was born in São Paulo and lived there virtually all of his life. As a child, he was a piano prodigy, and he later studied at the Music and Drama Conservatory of São Paulo. His formal education was solely in music, but at the same time, as Albert T. Luper records, he pursued persistent and solitary studies in history, art, and particularly poetry.[3] Andrade had a solid command of French, and read Rimbaud and the major Symbolists. Although he wrote poetry throughout his musical education, he did not think to do so professionally until the career as a professional pianist to which he aspired was no longer an option.

In 1913, his 14-year-old brother Renato died suddenly during a football game; Andrade left the Conservatory to stay at Araraquara, where his family had a farm. When he returned, his piano playing was afflicted intermittently by trembling of his hands. Although he ultimately did receive a degree in piano, he gave no concerts and began studying singing and music theory with an eye toward becoming a professor of music. At the same time, he began writing more seriously. In 1917, the year of his graduation, he published his first book of poems, Há uma Gota de Sangue em Cada Poema (There is a drop of blood in each poem), under the pseudonym Mário Sobral.[4] The book contains hints of Andrade's growing sense of a distinctive Brazilian identity, but it does so within the context of a poetry that (like most Brazilian poetry of the period) is strongly indebted to earlier European—particularly French—literature.[5]

His first book does not seem to have had an enormous impact, and Andrade broadened the scope of his writing. He left São Paulo for the countryside, and began an activity that would continue for the rest of his life: the meticulous documentation of the history, people, culture, and particularly music of the Brazilian interior, both in the state of São Paulo and in the wilder areas to the northeast.[6] He published essays in São Paulo magazines, accompanied occasionally by his own photographs, but primarily he accumulated massive amounts of information about Brazilian life and folklore. Between these trips, Andrade taught piano at the Conservatory, and became one of its professors in 1921.[7]

The Week of Modern Art

While these folklore-gathering trips were going on, Andrade developed a group of friends among young artists and writers in São Paulo, who, like him, were aware of the growing modernist movement in Europe. Several of them were later known as the Grupo dos Cinco (the Group of Five): Andrade, poets Oswald de Andrade (no relation) and Menotti del Picchia, and artists Tarsila do Amaral and Anita Malfatti. Malfatti had been to Europe before World War I, and introduced São Paulo to expressionism.[8] Jack E. Tomlins, the translator of Andrade's second book, describes in his introduction a particularly crucial event in the development of Andrade's modernist philosophy.[9] In 1920, he had recently met the modernist sculptor Victor Brecheret, and bought a sculpture from him entitled "Bust of Christ," which depicted Christ as a Brazilian with braided hair. His family (apparently to his surprise) was shocked and furious. Andrade retreated to his room alone, and later recalled, in a lecture translated by Tomlins, that—still "delirious"—he went out onto his balcony and "looked down at the square below without actually seeing it."

Noises, lights, the ingenuous bantering of the taxi drivers: they all floated up to me. I was apparently calm and was thinking about nothing in particular. I don't know what suddenly happened to me. I went to my desk, opened a notebook, and wrote down a title that had never before crossed my mind: Hallucinated City.[10]

Retaining that title (Paulicéia Desvairada, in Portuguese), Andrade worked on the book for the next two years. He very quickly produced a "barbaric canticle", as he called it in the same lecture, and then gradually edited it down to half its original size.

These poems were entirely different from his earlier formal and abstract work. The lines of verse vary greatly in length and in syntactical structure, consisting primarily of impressionistic and fragmented descriptions interspersed with seemingly overheard, disconnected bits of speech in São Paulo dialect.[11] The speaker of the poems often seems overwhelmed by the maze of dialogue that constantly interrupts him, as in "Colloque Sentimental":

A rua toda nua ... As casas sem luzes ... |

The street all naked ... The lightless houses ... |

After the poems were completed, Andrade wrote what he called an "Extremely Interesting Preface", in an attempt to explain in hindsight the poems' theoretical context (though Bruce Dean Willis has suggested that the theories of the preface have more to do with his later work than with Paulicéia[13]). The preface is self-deprecating ("This preface—although interesting—useless") but ambitious, presenting a theory not just of poetry but of the aesthetics of language, in order to explain the innovations of his new poems.[14] Andrade explains their tangle of language in musical terms:

There are certain figures of speech in which we can see the embryo of oral harmony, just as we find the germ of musical harmony in the reading of the symphonies of Pythagoras. Antithesis: genuine dissonance.[15]

He makes a distinction, however, between language and music, in that "words are not fused like notes; rather they are shuffled together, and they become incomprehensible."[15] However, as Willis has pointed out, there is a pessimism to the preface; in one of its key passages, it compares poetry to the submerged riches of El Dorado, which can never be recovered.[16]

In 1922, while preparing Paulicéia Desvairada for publication, Andrade collaborated with Malfatti and Oswald de Andrade in creating a single event that would introduce their work to the wider public: the Semana de Arte Moderna (Week of Modern Art).[8] The Semana included exhibitions of paintings by Malfatti and other artists, readings, and lectures on art, music, and literature. Andrade was the chief organizer and the central figure in the event, which was greeted with skepticism but was well-attended. He gave lectures on both the principles of modernism and his work in Brazilian folk music, and read his "Extremely Interesting Preface." As the climactic event of the Semana, he read from Paulicéia Desvairada. The poems' use of free verse and colloquial São Paulo expressions, though related to European modernist poems of the same period, were entirely new to Brazilians.[11] The reading was accompanied by persistent jeers, but Andrade persevered, and later discovered that a large part of the audience found it transformative. It has been cited frequently as the seminal event in modern Brazilian literature.[17]

The Group of Five continued working together in the 1920s, during which their reputations solidified and hostility to their work gradually diminished, but eventually the group split apart; Andrade and Oswald de Andrade had a serious (and public) falling-out in 1929.[18] New groups were formed out of the splinters of the original, and in the end many different modernist movements could trace their origins to the Week of Modern Art.

"The apprentice tourist"

Throughout the 1920s Andrade continued traveling in Brazil, studying the culture and folklore of the interior. He began to formulate a sophisticated theory of the social dimensions of folk music, which is at once nationalistic and deeply personal.[19] Andrade's explicit subject was the relationship between "artistic" music and the music of the street and countryside, including both Afro-Brazilian and Amerindian styles. The work was controversial for its formal discussions of dance music and folk music; those controversies were compounded by Andrade's style, which was at once poetic (Luper calls it "Joycean"[20]) and polemical.

His travels through Brazil became more than just research trips; in 1927, he started writing a travelogue called "The apprentice tourist" for the newspaper O Diario Nacional.[21] The column served as an introduction for cosmopolites to indigenous Brazil. At the same time, it served as an advertisement for Andrade's own work. A number of Andrade's photographs were published alongside the column, showing the landscape and people. Occasionally, Andrade himself would appear in them, usually filtered through the landscape, as in the self-portrait-as-shadow on this page. His photographs thus served to further his modernist project and his own work at the same time as their function in recording folklore.[22]

Though Andrade continued taking photographs throughout his career, these images from the 20s comprise the bulk of his notable work, and the 1927 series in particular. He was particularly interested in the capacity of photographs to capture or restate the past, a power he saw as highly personal. In the late 1930s, he wrote:

. . .the objects, the designs, the photographs that belong to my existence from some day in the past, for me always retain an enormous force for the reconstitution of life. Seeing them, I don't simply remember, but re-live with the same sensation and same old state, the day that I already lived. . .[23]

In many of the images, figures are shadowed, blurred, or otherwise nearly invisible, a form of portraiture that for Andrade became a kind of modernist sublime.[24]

Macunaíma

At the same time, Andrade was developing an extensive familiarity with the dialects and cultures of large parts of Brazil. He started to apply to prose fiction the speech-patterned technique he had developed in writing the poems of Hallucinated city. He wrote two novels during this period using these techniques: the first, Love, Intransitive Verb, was largely a formal experiment.;[26] the second, written shortly after and published in 1928, was Macunaíma, a novel about a man ("The hero without a character" is the subtitle of the novel) from an indigenous tribe who comes to São Paulo, learns its languages—both of them, the novel says: Portuguese and Brazilian—and returns.[27] The style of the novel is composite, mixing vivid descriptions of both jungle and city with abrupt turns toward fantasy, the style that would later be called magical realism. Linguistically, too, the novel is composite; as the rural hero comes into contact with his urban environment, the novel reflects the meeting of languages.[28] Relying heavily on the primitivism that Andrade learned from the European modernists, the novel lingers over possible indigenous cannibalism even as it explores Macunaíma's immersion in urban life. Critic Kimberle S. López has argued that cannibalism is the novel's driving thematic force: the eating of cultures by other cultures.[29]

Formally, Macunaíma is an ecstatic blend of dialects and of the urban and rural rhythms that Andrade was collecting in his research. It contains an entirely new style of prose—deeply musical, frankly poetic, and full of gods and almost-gods, yet containing considerable narrative momentum. At the same time, the novel as a whole is pessimistic. It ends with Macunaíma's willful destruction of his own village; despite the euphoria of the collision, the meeting of cultures the novel documents is inevitably catastrophic. As Severino João Albuquerque has demonstrated, the novel presents "construction and destruction" as inseparable. It is a novel of both power (Macunaíma has all kinds of strange powers) and alienation.[30]

Even as Macunaíma changed the nature of Brazilian literature in an instant—Albuquerque calls it "the cornerstone text of Brazilian Modernism"—the inner conflict in the novel was a strong part of its influence.[30] Modernismo, as Andrade depicted it, was formally tied to the innovations of recent European literature and based on the productive meeting of cultural forces in Brazil's diverse population; but it was fiercely nationalistic, based in large part on distinguishing Brazil's culture from the world and on documenting the damage caused by the lingering effects of colonial rule. At the same time, the complex inner life of its hero suggests themes little explored in earlier Brazilian literature, which critics have taken to refer back to Andrade himself. While Macunaíma is not autobiographical in the strict sense, it clearly reflects and refracts Andrade's own life. Andrade was a mulatto; his parents were landowners but were in no sense a part of Brazil's Portuguese pseudo-aristocracy. Some critics have paralleled Andrade's race and family background to the interaction between categories of his character Macunaíma.[31] Macunaíma's body itself is a composite: his skin is darker than that of his fellow tribesmen, and at one point in the novel, he has an adult's body and a child's head. He himself is a wanderer, never belonging to any one place.

Other critics have argued for similar analogues between Andrade's sexuality and Macunaíma's complex status.[18] Though Andrade was not openly gay, and there is no direct evidence of his sexual practices, many of Andrade's friends have reported after his death that he was clearly interested in men (the subject is only reluctantly discussed in Brazil).[32] It was over a pseudonymous accusation of effeminacy that Andrade broke with Oswald de Andrade in 1929.[18] Macunaíma prefers women, but his constant state of belonging and not belonging is associated with sex. The character is sexually precocious, starting his romantic adventures at the age of six, and his particular form of eroticism seems always to lead to destruction of one kind or another.

Inevitably, Macunaíma's polemicism and sheer strangeness have become less obvious as it has grown ensconced in mainstream Brazilian culture and education. Once regarded by academic critics as an awkwardly constructed work of more historical than literary importance, the novel has come to be recognized as a modernist masterpiece whose difficulties are part of its aesthetic.[33] Andrade is a national cultural icon; his face has appeared on the Brazilian currency. A film of Macunaíma was made in 1969, by Brazilian director Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, updating Andrade's story to the 1960s and shifting it to Rio de Janeiro; the film was rereleased internationally in 2009.[34]

Late life and musical research

Andrade was not directly affected by the Revolution of 1930, in which Getúlio Vargas seized power and became dictator, but he belonged to the landed class the Revolution was designed to displace, and his employment prospects declined under the Vargas regime.[35] He was able to remain at the Conservatory, where he was now Chair of History of Music and Aesthetics. With this title he became a de facto national authority on the history of music, and his research turned from the personal bent of his 1920s work to textbooks and chronologies. He continued to document rural folk music, and during the 1930s made an enormous collection of recordings of the songs and other forms of music of the interior. The recordings were exhaustive, with a selection based on comprehensiveness rather than an aesthetic judgment, and including context, related folktalkes, and other non-musical sound.[36] Andrade's techniques were influential in the development of ethnomusicology in Brazil and predate similar work done elsewhere, including the well-known recordings of Alan Lomax. He is credited with coining the word "popularesque," which he defined as imitations of Brazilian folk music by erudite urban musicians ("erudite" is generally a deprecation in Andrade's vocabulary).[37] The word continues to have currency in discussion of Brazilian music as both a scholarly and nationalist category.[38]

In 1935, during an unstable period in Vargas's government, Andrade and writer and archaeologist Paulo Duarte, who had for many years desired to promote cultural research and activity in the city through a municipal agency, were able to create a unified São Paulo Department of Culture (Departamento de Cultura e Recreação da Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo). Andrade was named founding director.[39] The Department of Culture had a broad purview, overseeing cultural and demographic research, the construction of parks and playgrounds, and a considerable publishing wing. Andrade approached the position with characteristic ambition, using it to expand his work in folklore and folk music while organizing myriad performances, lectures, and expositions. He moved his collection of recordings to the Department, and expanding and enhancing it became one of the Department's chief functions, overseen by Andrade's former student, Oneyda Alvarenga. The collection, called the Discoteca Municipal, was "probably the largest and best-organized in the entire hemisphere."[36]

At the same time, Andrade was refining his theory of music. He attempted to pull together his research into a general theory. Concerned as always with Modernismo's need to break from the past, he formulated a distinction between the classical music of 18th- and 19th-century Europe, and what he called the music of the future, which would be based simultaneously on modernist breakdowns of musical form and on an understanding of folk and popular music. The music of the past, he said, was conceived in terms of space: whether counterpoint, with its multiple voices arranged in vertical alignment, or the symphonic forms, in which the dominant voice is typically projected on top of a complex accompaniment. Future music would be arranged in time rather than space: "moment by moment" (in Luper's translation). This temporal music would be inspired not by "contemplative remembrance", but by the deep longing or desire expressed by the Portuguese word saudade.[40]

Through his position at the Department of Culture in this period, he was able to assist Dina Lévi-Strauss and her husband, Claude Lévi-Strauss with films they were making based on field research in Mato Grosso and Rondônia.[41]

Andrade's position at the Department of Culture was abruptly revoked in 1937, when Vargas returned to power and Duarte was exiled. In 1938 Andrade moved to Rio de Janeiro to take up a post at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. While there he directed the Congresso da Língua Nacional Cantada (Congress of National Musical Language), a major folklore and folk music conference. He returned to São Paulo in 1941, where he worked on a collected edition of his poetry.[42]

Andrade's final project was a long poem called "Meditação Sôbre o Tietê." The work is dense and difficult, and was dismissed by its early critics as "without meaning", although recent work on it has been more enthusiastic. One critic, David T Haberly, has compared it favorably to William Carlos Williams's Paterson, a dense but influential unfinished epic using composite construction.[43] Like Paterson, it is a poem about a city; the "Meditação" is centered on the Tietê River, which flows through São Paulo. The poem is simultaneously a summation of Andrade's career, commenting on poems written long before, and a love poem addressed to the river and to the city itself. In both cases, the poem hints at a larger context: it compares the river to the Tagus in Lisbon and the Seine in Paris, as if claiming an international position for Andrade as well. At the same time, the poem associates both Andrade's voice and the river with "banzeiro," a word from the Afro-Brazilian musical tradition: music that can unite man and river.[44] The poem is the definitive and final statement of Andrade's ambition and his nationalism.[45]

Andrade died at his home in São Paulo of a heart attack on February 25, 1945, at the age of 52.[46] Because of his tenuous relationship with the Vargas regime, the initial official reaction to his career was muted. However, the publication of his Complete Poems in 1955 (the year after Vargas's death) signalled the start of Andrade's canonization as one of the cultural heroes of Brazil. On February 15, 1960, the municipal library of São Paulo was renamed Biblioteca Mário de Andrade.[47]

Partial bibliography

Poetry

Published posthumously:

|

Essays, criticism, and musicology

Posthumous:

|

Novels

|

Stories and Crônicas

Posthumous:

JournalsPosthumous:

|

English translations

- Fraulein (Amar, Verbo Intransitivo). Trans. Margaret Richardson Hollingsworth. New York: Macaulay, 1933.

- Popular Music and Song in Brazil. 1936. Trans. Luiz Victor Le Cocq D'Oliveira. Sponsored by the Ministry of State for Foreign Affairs of Brazil: Division of Intellectual Cooperation. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1943.

- Portuguese version published in the second edition (1962) of Ensaio sobre a Música Brasileira .

- Hallucinated City (Paulicea Desvairada). Trans. Jack E. Tomlins. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1968.

- Macunaíma. Trans. E.A. Goodland. New York: Random House, 1984.

- Brazilian Sculpture: An Identity in Profile/Escultura Brasileira: Perfil de uma Identidate. Catalog of exhibition in English and Portuguese. Includes text by Mário de Andrade and others. Ed. Élcior Ferreira de Santana Filho. São Paulo, Brazil: Associação dos Amigos da Pinateca, 1997.

Footnotes

- See Lokensgard and Nunes, in particular, for a detailed account of Andrade's influence in literature, and Hamilton-Tyrell for Andrade's influence in ethnomusicology and music theory.

- Foster, 76.

- Luper 43.

- Suárez and Tomlins, 35.

- Nunes, 72–73; see also Hamilton-Tyrell, 32 note 71, and Perrone, 62, for Andrade's French influences.

- Gouveia, 101–102.

- Hamilton-Tyrell, 9.

- Amaral and Hastings, 14.

- Tomlins, Introduction to Hallucinated City (see English translations), xv.

- Tomlins, Introduction to Hallucinated City (English), xvi.

- Foster, 94–95.

- Hallucinated City (English), 69.

- Willis, 261.

- Tomlins, Introduction to Hallucinated City, xiii–xiv.

- Hallucinated City (English) 13.

- Willis, 262.

- Foster, 75.

- See Green, section "Miss São Paulo."

- Luper 44–45.

- Luper 44.

- Gabara 38.

- Gabara compares the photographs to Andrade's extensive art collection, both of which "reflect his interest in portraiture as a modernist art practice" (Gabara, 35); but photography is more complicated, since its European origins and Andrade's native subjects place the photographs "at a site too far from Europe to be unproblematically modern, yet too distant from the 'primitive' to be authentically Other; they were neither sufficiently Parisian nor Amazonian" (Gabara, 39).

- "O homem que se achou." In Será o Benedito! Artigos publicados no Suplemento em Rotogravura de O Estado de S. Paulo, presented by Telê Ancona Lopez. (São Paulo: Editora da PUC-SP), 82. Quoted in Gabara, 55.

- Gabara, 40.

- "Crouched at my desk in São Paulo / At my house in the rua Lopes Chaves / In a trice I felt a chill inside me. . ." (Andrade, "Descobrimento," 1927; translation from Bernard McGuirk, Latin American Literature: Symptoms, Risks, and Strategies of Post-structuralist Criticism, London: Routledge, 1997, 47).

- Lokensgard, 138–39.

- Mark Lokensgard examines in detail Andrade's "project of creating a new Brazilian literary language" (Lokensgard, 136), including the role of Macunaíma in that creation (138).

- López, 26–27.

- Though Andrade's desire may be that direct, cannibalism and primitivism, López argues, cannot make simple the novel's complex relationship to European-influenced culture: "the goal of incorporating popular speech into erudite literature is not only a cannibalizing, but to a certain extent also a colonializing, endeavor" (López 35).

- Albuquerque 67.

- Nunes 72–73.

- In addition to Green, the issue of Andrade's sexuality is most prominently discussed in Esther Gabara, Errant Modernism: The Ethos of Photography in Mexico and Brazil (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2009), 36–74.

- See López, 25–27, for a discussion of the novel's place within modernism; Maria Luisa Nunes calls the novel the Brazilian modernist movement's "masterpiece," a not uncommon conclusion (Nunes, 70).

- Johnson, Reed (June 17, 2009). "Satire, in the face of repression". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- Luper, 5–58.

- Luper 47.

- Filho and Herschmann 347–48.

- For example, Manoel Aranha Corrêa do Lago cites musicologist Luiz Heitor's critique of the popularesque in Brazilian music publishing (Corrêa do Lago, "Brazilian Sources in Milhaud's Le Boeuf sur le Toit: A Discussion and a Musical Analysis," Latin American Music Review 23, 1 [2002], 4).

- Suárez and Tomlins, 20.

- From Andrade's Pequena história da música, quoted and translated by Luper, 52.

- Jean-Paul Lefèvre, "Les missions universitaires françaises au Brésil dans les années 1930," Vingtième Siècle 38 (1993), 28.

- Suárez and Tomlins, 21

- Haberly 277–79.

- Haberly, 279.

- Haberly, 281.

- Suárez and Tomlins, 192.

- "Histórico: Biblioteca Mário de Andrade". Official website for City of São Paulo. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

References

- Albuquerque, Severino João. "Construction and Destruction in Macunaíma." Hispania 70, 1 (1987), 67–72.

- Amaral, Aracy and Kim Mrazek Hastings. "Stages in the Formation of Brazil's Cultural Profile." Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 21 (1995), 8–25.

- Filho, João Freire and Micael Herschmann. "Debatable Tastes: Rethinking Hierarchical Distinctions in Brazilian Music." Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 12, 3 (2003), 347–58.

- Foster, David, "Some Formal Types in the Poetry of Mário de Andrade," Luso-Brazilian Review 2,2 (1965), 75–95.

- Gabara, Esther. "Facing Brazil: The Problem of Portraiture and the Modernist Sublime." CR: The New Centennial Review 4,2 (2004), 33–76.

- Gouveia, Saulo. "Private Patronage in Early Brazilian Modernism: Xenophobia and Internal Colonization Coded in Mário de Andrade's Noturno de Belo Horizonte.'" Luso-Brazilian Review 46,2 (2009), 90–112.

- Green, James N. "Challenging National Heroes and Myths: Male Homosexuality and Brazilian History." Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe 12, 1 (2001). Online.

- Haberly, David T. "The Depths of the River: Mário de Andrade's Meditação Sôbre o Tietê." Hispania 72,2 (1989), 277–282.

- Hamilton-Tyrell, Sarah, "Mário de Andrade, Mentor: Modernism and Musical Aesthetics in Brazil, 1920–1945," Musical Quarterly 88,1 (2005), 7–34.

- Lokensgard, Mark. "Inventing the Modern Brazilian Short Story: Mário de Andrade's Literary Lobbying." Luso-Brazilian Review 42,1 (2005), 136–153.

- López, Kimberle S. "Modernismo and the Ambivalence of the Postcolonial Experience: Cannibalism, Primitivism, and Exoticism in Mário de Andrade's Macunaíma". Luso-Brazilian Review 35, 1 (1998), 25–38.

- Luper, Albert T. "The Musical Thought of Mário de Andrade (1893–1945)." Anuario 1 (1965), 41–54.

- Nunes, Maria Luisa. "Mário de Andrade in 'Paradise'." Modern Language Studies 22,3 (1992), 70–75.

- Perrone, Charles A. "Performing São Paulo: Vanguard Representations of a Brazilian Cosmopolis." Latin American Music Review 22, 1 (2002), 60–78.

- Suárez, José I., and Tomlins, Jack E., Mário de Andrade: The Creative Works (Cranbury, New Jersey: Associated University Presses, 2000).

- Willis, Bruce Dean. "Necessary Losses: Purity and Solidarity in Mário de Andrade's Dockside Poetics." Hispania 81, 2 (1998), 261–268.

External links

- Biography from releituras.com (in Portuguese).

- Official site, Mário de Andrade Library, São Paulo

- Online, English-language presentation of Andrade's Mission for Folklore Research

- Barra Funda, S. Paulo

- Works by or about Mário de Andrade at Internet Archive

- Works by Mário de Andrade at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)